Employee voice – defined as proactively expressing work-related suggestions or concerns – is an important form of organizational citizenship behavior aimed at improving organizational functioning, often changing and challenging the status quo (LePine & Van Dyne, Reference LePine and Van Dyne2001; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Qu, Zhang, Hao, Tang, Zhao and Si2019). Several profound reviews have concluded that voice behavior benefits many work outcomes, such as performance, productivity, innovation, and creativity (Bashshur & Oc, Reference Bashshur and Oc2015; Morrison, Reference Morrison2014). Given the importance of voice behavior, many studies have also been exploring the antecedents of voice behavior, mainly including personality, leadership, and contextual factors (Chamberlin, Newton, & Lepine, Reference Chamberlin, Newton and Lepine2017; Janssen & Gao, Reference Janssen and Gao2015; Li, Liang, & Farh, Reference Li, Liang and Farh2020). Perceived organizational politics (POP), defined as ‘the subjective evaluation of the self-interested behavior of colleagues and superiors’ (Ferris, Ellen, McAllister, & Maher, Reference Ferris, Ellen, McAllister and Maher2019), is an inevitable aspect of work life (Hochwarter, Ferris, Laird, Treadway, & Gallagher, Reference Hochwarter, Ferris, Laird, Treadway and Gallagher2010, Reference Hochwarter, Rosen, Jordan, Ferris, Ejaz and Maher2020). This common organizational contextual factor has a significant impact on organizational behavior (Ferris et al., Reference Ferris, Ellen, McAllister and Maher2019). However, its impact on voice behavior has not been fully addressed in the extant literature. Therefore, in this study, we will focus on the relationship between POP and voice behavior.

Little is known about the underlying mechanism of POP on voice behavior, which would explain how voice behavior is affected by organizational context. POP indicates that there are a lot of unwritten rules and powers influencing the allocation of resources in the organization (Li, Liang, & Farh, Reference Li, Liang and Farh2020), and employees often need to spend a lot of time and effort to cope with this environment (Chang, Rosen, & Levy, Reference Chang, Rosen and Levy2009). Therefore, most studies regard POP as a high-stress and highly destructive environmental factor leading to negative outcomes (Bedi & Schat, Reference Bedi and Schat2013; Khan, Khan, & Gul, Reference Khan, Khan and Gul2019), such as decreased satisfaction, commitment, and job performance (Chang, Rosen, & Levy, Reference Chang, Rosen and Levy2009; Rosen, Harris, & Kacmar, Reference Rosen, Harris and Kacmar2009). Voice behavior is a strategic resource acquisition behavior, as well as a resource consumption behavior (Ng & Feldman, Reference Ng and Feldman2012), and the conservation of resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1989) is used to explain how stressful environment affects employee behavior (i.e., resource conservation behavior or resource investment behavior). Therefore, this study will investigate the underlying process of POP on voice behavior using COR theory. The self-serving environment of POP leads employees to develop a sense of self-protection, which triggers their defensive mechanisms to prevent the loss of their resources (Khalid & Ahmed, Reference Khalid and Ahmed2016; Van Dyne, Ang, & Botero, Reference Van Dyne, Ang and Botero2003). Territoriality is a defense-oriented psychological ownership, which triggers protective behaviors, such as marking and defending, in employees to protect their resources (Avey, Avolio, Crossley, & Luthans, Reference Avey, Avolio, Crossley and Luthans2009). Therefore, in line with COR theory, POP is likely to be positively associated with territoriality, and thus, further influences other work outcomes (e.g., voice behavior).

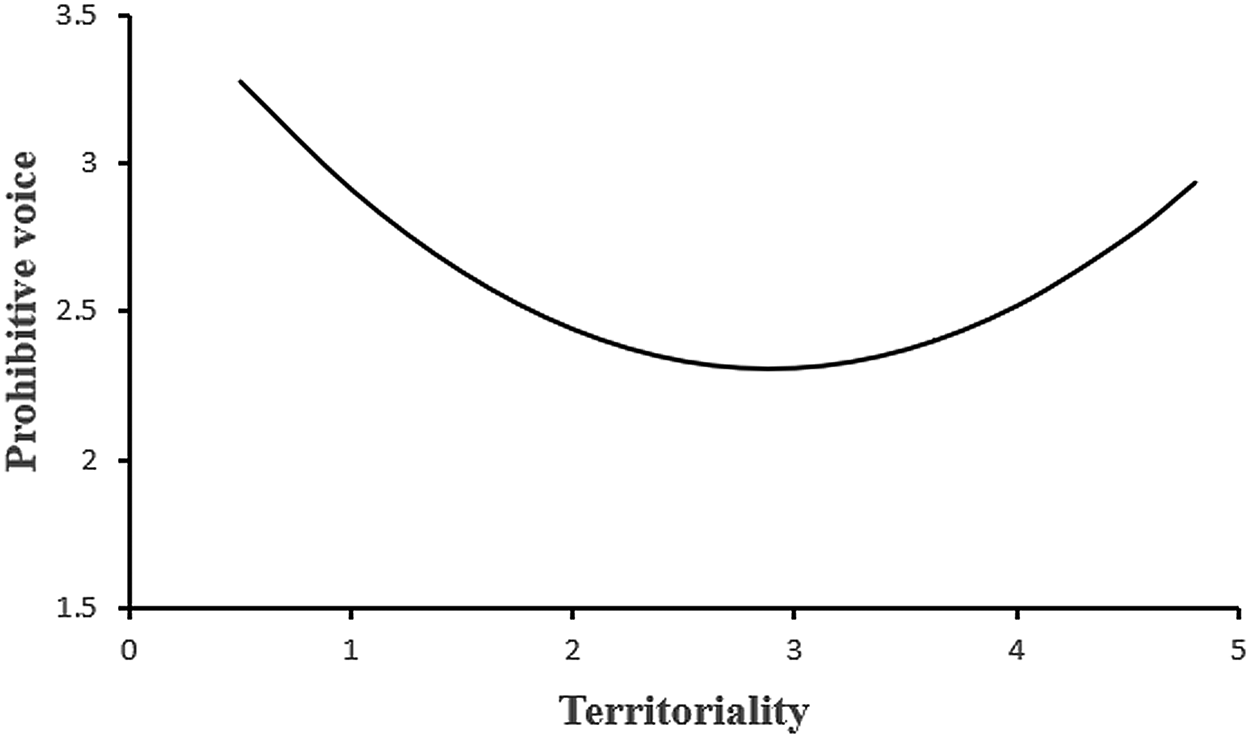

Territoriality is a type of sense of ownership that stimulates employees to construct, communicate, maintain, and restore their territories in the social environment (Brown, Lawrence, & Robinson, Reference Brown, Lawrence and Robinson2005). To the best of our knowledge, there is no study on the territoriality-voice relationship. Based on COR theory, when territoriality is low, employees have a weaker sense of boundaries and are more agreeable. Employees consume less resources to deal with various relationships, so they have more time and energy to engage in pro-organizational behaviors, like voice behavior. When territoriality is moderate, employees begin to develop a stronger sense of boundaries and will increase their marking and defensive behaviors, thus consuming more resources, such as time and energy (Brown, Lawrence, & Robinson, Reference Brown, Lawrence and Robinson2005; Sundstrom & Altman, Reference Sundstrom and Altman1974). Thus, they have lesser time and energy to consider other pro-organizational behaviors such as voice behavior. When territoriality is high, the employees' sense of boundaries is very strong (Avey et al., Reference Avey, Avolio, Crossley and Luthans2009; Fennimore, Reference Fennimore2020; Van Dyne & Pierce, Reference Van Dyne and Pierce2004). However, relationships are clearer and simpler at this time, and employees do not need to consume much time and energy to deal with relationships (Altman & Haythorn, Reference Altman and Haythorn1967; Brown, Lawrence, & Robinson, Reference Brown, Lawrence and Robinson2005), thus leaving more time and energy to employ pro-organizational behaviors such as voice behavior. Summarily, the above argument means that when territoriality ranges from low to moderate, voice behavior gradually decreases, when territoriality ranges from moderate to high, voice behavior gradually increases. Thus, we propose that territoriality is curvilinear in relation to voice behavior. Further, we examine the curvilinear indirect influence of POP on voice behavior via territoriality. Figure 1 depicts the conceptual model.

Fig. 1. The conceptual model.

The research aimed to verify the influence of POP on voice through territoriality. As such, there are several contributions. First, several existing studies on POP-voice suggest that POP environments increase the risk of voice, considering voice as a resource consumption behavior (Bergeron & Thompson, Reference Bergeron and Thompson2020; Li, Wu, Liu, Kwan, & Liu, Reference Li, Wu, Liu, Kwan and Liu2014, Reference Li, Liang and Farh2020). However, in addition to consuming resources, voice can also help employees to acquire resources (Ferris et al., Reference Ferris, Ellen, McAllister and Maher2019; Fuller, Barnett, Hester, Relyea, & Frey, Reference Fuller, Barnett, Hester, Relyea and Frey2007). Therefore, this paper discusses the relationship between POP and voice from the perspective of COR theory, which can help us gain a more comprehensive understanding of the POP-voice linkage where, in the context of POP, employees will treat voice behavior as more akin to a resource investment or resource consumption behavior. Second, most previous research has focused on the harmfulness of territoriality (Brown & Baer, Reference Brown and Baer2015; Huo, Cai, Luo, Men, & Jia, Reference Huo, Cai, Luo, Men and Jia2016). However, as Avey et al., (Reference Avey, Avolio, Crossley and Luthans2009) argued, territoriality may also bring benefits, but there is little research on this area. The investigation of the U-shaped relationship between territoriality and voice behavior in this study enriches the literature on the outcome of territoriality. Third, previous studies have suggested that the uncertainty of POP can bring many negative outcomes, but the impact of POP on territoriality has not been explored. Using COR theory, we examine how POP influences territoriality and further influences voice behavior. This intermediary provides a new explanation mechanism for POP-voice linkage from a preventative ownership perspective (i.e., preventing resource loss rather than increasing resources, per Avey et al., Reference Avey, Avolio, Crossley and Luthans2009) to more comprehensively explain how employees consider the investment and consumption of voice behavior in the POP environment.

Literature review and hypotheses

Pop and territoriality

Organizational politics involves the use of power and tactics by employees to influence others for self-serving interests, which tends to increase conflicts and disharmony among organizational members (Ferris, Frink, Galang, Zhou, Kacmar, & Howard, Reference Ferris, Frink, Galang, Zhou, Kacmar and Howard1996; Hochwarter, Ellen, & Ferris, Reference Hochwarter, Ellen and Ferris2014; Ladebo, Reference Ladebo2006; Li et al., Reference Li, Wu, Liu, Kwan and Liu2014; Vigoda, Reference Vigoda2001). POP refers to the perceived extent of organizational political behavior, rather than the actual behavior itself (Ferris, Adams, Kolodinsky, Hochwarter, & Ammeter, Reference Ferris, Adams, Kolodinsky, Hochwarter, Ammeter, Yammarino and Dansereau2002). The higher the POP, the more unfair and unjust the employees consider the organization (Ferris & Kacmar, Reference Ferris and Kacmar1992; Vigoda, Reference Vigoda2000). In such a situation, employees may perceive many uncertainties and ambiguities in the organization such as reward rules, interpersonal relationships, and promotion channels (Jam, Donia, Raja, & Ling, Reference Jam, Donia, Raja and Ling2017; Li, Liang, & Farh, Reference Li, Liang and Farh2020; Treadway, Ferris, Hochwarter, Perrewé, Witt, & Goodman, Reference Treadway, Ferris, Hochwarter, Perrewé, Witt and Goodman2005). This, in turn, increases suspicion, distrust, and usurpation among employees, thus increasing unpredictability (Ferris, Russ, & Fandt, Reference Ferris, Russ, Fandt, Glacalone and Rosenfeld1989; Li, Liang, & Farh, Reference Li, Liang and Farh2020; Vigoda, Reference Vigoda2001). Even the creators of organizational politics can feel the unpredictability of the environment. After all, in a POP organization, it is generally impossible to have only one coalition (i.e., interest group), and the creators will still worry about the usurpation of benefits (Ferris et al., Reference Ferris, Frink, Galang, Zhou, Kacmar and Howard1996; Landells & Albrecht, Reference Landells and Albrecht2017). Further, this distrust and unpredictability makes employees feel like their resources are threatened, which puts them in a defensive and cautious state to maintain and protect their personal resources (i.e., territoriality).

The study of territoriality began with the study of animal behavior (Edney, Reference Edney1974; Sundstrom & Altman, Reference Sundstrom and Altman1974). Capable animals mark, establish, and defend the regions (i.e., territories) where they acquire resources for survival (Wagle & Kaminski, Reference Wagle and Kaminski1984). Subsequently, scholars began to study human territoriality, focusing on the defense of physical space (Peng, Reference Peng2013). Territoriality was introduced into the field of organizational behavior by Brown, Lawrence, and Robinson (Reference Brown, Lawrence and Robinson2005), which refers to the behavioral expression of an individual's desire to possess the target, including tangible (e.g., project, workspace) and intangible objects (e.g., ideas, knowledge), not just physical space. Brown, Lawrence, and Robinson (Reference Brown, Lawrence and Robinson2005) contended that territorial behavior includes both marking and defending behaviors, such as enclosing a desk with personal items to signal that it is my office area, and often declaring that I am the person in charge of the project.

In addition to emphasizing the behavioral aspect of territoriality, as defined by Brown, Lawrence, and Robinson (Reference Brown, Lawrence and Robinson2005), some scholars emphasized the motivational aspect of territoriality, that is, a psychological state which can further influence employees' work behavior. For example, Malmberg (Reference Malmberg1980) defined territoriality as the impetus to establish permanent or temporary control over a territory. Avey et al. (Reference Avey, Avolio, Crossley and Luthans2009) indicated that territoriality is a more defensive dimension of psychological ownership and emerges when the possessiveness of individuals' ‘targets’ is threatened, and it can motivate employees to engage in behaviors that prevent infringement. In short, in an organization, territoriality is a perception of a set of rights over a territory (e.g., who it belongs to, who can use it), and employees care a lot about the ownership of the territory (Peng, Reference Peng2013). This paper takes Avey et al. (Reference Avey, Avolio, Crossley and Luthans2009) view of territoriality and focuses on its motivational aspect.

COR theory proposes that people accumulate, protect, and retain valuable and limited resources (Halbesleben, Neveu, Paustian-Underdahl, & Westman, Reference Halbesleben, Neveu, Paustian-Underdahl and Westman2014). This theory comprises two basic tenets: protect existing resources (conservation) and acquire additional resources (acquisition) (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1989, Reference Hobfoll2001). When an individual loses resources or is threatened with the loss of resources, he or she becomes more defensive (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001; Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu, & Westman, Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018). As mentioned earlier, the uncertainties and ambiguities in high POP environments make employees afraid of losing their resources, or even actually lose their resources. This situation makes employees more defensive, i.e., increased territoriality (Avey et al., Reference Avey, Avolio, Crossley and Luthans2009). Specifically, the distrust caused by self-interested (POP) environments instills in employees the worry that their resources will be taken by others, and hence, reinforcing employees' propensity to mark their territorial boundaries (Brown, Crossley, & Robinson, Reference Brown, Crossley and Robinson2014). Furthermore, in a high self-serving climate, interests (e.g., rewards, promotions, projects) are more likely to be manipulated, thus promoting employees' momentum to claim and defend the ownership of relevant territories (Avey et al., Reference Avey, Avolio, Crossley and Luthans2009; Brown & Robinson, Reference Brown and Robinson2011; Khalid & Ahmed, Reference Khalid and Ahmed2016; Li, Liang, & Farh, Reference Li, Liang and Farh2020).

These higher tendencies to mark, claim, and defend territories in high POP environments are the manifestations of higher territoriality. In contrast, Brown, Crossley, and Robinson (Reference Brown, Crossley and Robinson2014) proposed that employees reduce territorial behaviors in an environment of trust. Gardner, Munyon, Hom, and Griffeth (Reference Gardner, Munyon, Hom and Griffeth2018) suggested that infringement losses increase managers' efforts to implement territorial strategies. Whereas in a low POP environment, an organization is fairer and more transparent, and employees trust each other more (Ferris & Kacmar, Reference Ferris and Kacmar1992). They respect each other's contributions and do not seek to usurp others' interests (Brown, Crossley, & Robinson, Reference Brown, Crossley and Robinson2014). Consequently, employees are not concerned with marking and defending their territories, which indicates low territoriality. In conclusion, we proposed the hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis 1: Perceived organizational politics is positively correlated with territoriality.

Territoriality and employees voice behavior

Employee voice indicates an active, discretionary, and voluntary behavior conducted by employees to facilitate the healthy functioning of the organization via expressing suggestions or concerns to coworkers and superiors (Morrison, Reference Morrison2014). Liang, Farh, and Farh (Reference Liang, Farh and Farh2012) divided voice behavior into promotive and prohibitive voice behaviors based on the different foci of voice content. The former focuses on coming up with future-oriented novel ideas and suggestions to improve the status quo and make the organization better, while the latter focuses on identifying existing or impending mistakes and concerns to prevent losses (Liu, Zhou, & Sheng, Reference Liu, Zhou and Sheng2021). The goal of employee voice behavior is to promote the better development of the organization. This good motivation often helps individuals to improve their image and win praise from colleagues and superiors (Lin & Johnson, Reference Lin and Johnson2015; Van Dyne & LePine, Reference Van Dyne and LePine1998). However, employees must consume certain resources (e.g., time, energy) to identify problems or generate good ideas for their voice behavior (Song, Gu, Wu, & Xu, Reference Song, Gu, Wu and Xu2019), and undertake the risk of being misunderstood (Burris, Reference Burris2012; Hsiung & Tsai, Reference Hsiung and Tsai2017; Li et al., Reference Li, Wu, Liu, Kwan and Liu2014). Thus, overall, voice behavior may lead to both the accumulation and consumption of resources by employees.

The COR theory holds that the initial amount of resources has a significant impact on individuals' investment decisions. When people have more resources, they tend to have more opportunities and thus choose to invest in obtaining more resources. In contrast, when there are fewer resources, employees are more willing to conserve existing resources (Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018). Marking and defending territories require the consumption of significant amounts of time, energy, and cognitive resources (Brown, Lawrence, & Robinson, Reference Brown, Lawrence and Robinson2005). Therefore, different territorial behaviors require the consumption of different amounts of resources, thus affecting the remaining pool of available resources for employees.

When territoriality is low, there is limited or no need to guard against others encroaching on territory (e.g., ideas, projects, workplaces) or to mark and defend, thus consuming fewer resources (Monaghan & Ayoko, Reference Monaghan and Ayoko2019; Peng, Reference Peng2013). Consequently, employees store more resources so as to invest their existing resources in obtaining additional resources (Halbesleben et al., Reference Halbesleben, Neveu, Paustian-Underdahl and Westman2014). Voice is an important investment tool that can help employees gain more resources, such as rewards and promotions, by improving their image, ratings, and insider status (Gong, Van Swol, Li, & Gilal, Reference Gong, Van Swol, Li and Gilal2021; Van Dyne & LePine, Reference Van Dyne and LePine1998; Zhao, Wu, & Gu, Reference Zhao, Wu and Gu2022). Additionally, voice behavior enables organizations to function more effectively (McClean, Martin, Emich, & Woodruff, Reference McClean, Martin, Emich and Woodruff2018; Morrison, Reference Morrison2011, Reference Morrison2014). As such, employees will be more likely to benefit from better performing organizations. Therefore, when territoriality is low, employees will increase their voice behavior and regard their voice as an investment, including promotive voice and prohibitive voice.

When territoriality ranges from low to moderate, employees' sense of territorial boundaries becomes relatively stronger; however, at this point, their territories may not have clear boundaries or established patterns (Sundstrom & Altman, Reference Sundstrom and Altman1974). Therefore, employees increase territorial marking and defending behaviors, which requires the consumption of several resources, thus reducing the employees' resource pool (Brown, Lawrence, & Robinson, Reference Brown, Lawrence and Robinson2005; Sundstrom & Altman, Reference Sundstrom and Altman1974). According to COR theory, fewer resources encourage employees to use the resource conservation tenet. As mentioned previously, voice behavior is a resource-consuming behavior, and therefore, employees will reduce voice behavior at this time (Kim, Lee, Oh, & Lee, Reference Kim, Lee, Oh and Lee2019). Additionally, while voice may provide benefits to employees, it also entails risks for employees such as offending stakeholders and being regarded as troublemakers (Li et al., Reference Li, Wu, Liu, Kwan and Liu2014). When territoriality increase to moderate from low, organizational members become more defensive and vigilant, and thus hesitant to undertake risks to obtain additional resources (Avey et al., Reference Avey, Avolio, Crossley and Luthans2009; Ng & Feldman, Reference Ng and Feldman2012). This is because guardedness reduces the chances of voice behavior adoption and increases the possibility of misunderstandings, leading to further loss of resources (e.g., retaliated) (Hassan, Reference Hassan2015; Li, Liang, & Farh, Reference Li, Liang and Farh2020). Therefore, in such cases, the investment nature of voice is less likely to be considered. In summary, when territoriality goes from low to moderate, voice behavior (including promotive voice and prohibitive voice) will decrease.

When territoriality becomes high, organizational members have strong psychological ownership of their territories and regard them as an extension of themselves (Avey et al., Reference Avey, Avolio, Crossley and Luthans2009; Fennimore, Reference Fennimore2020). Thus, the employees' sense of defense and boundaries will be very strong. However, after a period of territorial behavior during moderate territoriality, by this time, the territorial boundaries of the organization are often formed and determined – the pattern of the organization is already established (Brown, Lawrence, & Robinson, Reference Brown, Lawrence and Robinson2005). Members tend to respect this territorial boundary and do not spend time and energy marking and defending it (Brown, Lawrence, & Robinson, Reference Brown, Lawrence and Robinson2005). In addition, explicit and clear boundaries simplify the relationships (Altman & Haythorn, Reference Altman and Haythorn1967), reducing conflict and facilitating a more efficient allocation of organizational resources (Brown, Lawrence, & Robinson, Reference Brown, Lawrence and Robinson2005; Edney, Reference Edney1974). All of these contribute to employees preserving more resources. Therefore, based on COR theory, when territoriality is high, employees have more resources to engage in investment behaviors, such as promotive and prohibitive voice. Further, based on the argument that territoriality progresses from low to moderate to high, we formulated the hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis 2: Territoriality demonstrates U-shaped relationships with both promotive (2a) and prohibitive (2b) voice. Specifically, higher and lower territoriality correspond to higher promotive voice/prohibitive voice, and a moderate level of territoriality corresponds to lower promotive voice/prohibitive voice.

Territoriality as a mediator

Above, we delineated the relationships between POP and territoriality as well as territoriality and employee voice behavior. COR theory suggests that when an individual loses resources or is threatened with the loss of resources, they become more defensive, thus affecting their future investment behavior (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001; Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018). Employees in a POP environment face the risk of resource usurpation, so that they will become more defensive (i.e., territoriality), affecting their subsequent behaviors, such as voice behavior (Avey et al., Reference Avey, Avolio, Crossley and Luthans2009; Vigoda, Reference Vigoda2001). So, territoriality conveys the impact of POP on voice behavior.

How the intermediary transfers the role of POP on voice behavior can be elaborated as follows: First, with the increase of POP, self-interested behaviors increase, and employees feel more likely to lose resources, which, according to COR theory, makes employees more defensive (i.e., territoriality). Therefore, POP will be positively related to territoriality. Next, with different territoriality, the amount of territorial behavior needing to consume several resources varies, which affects the resource pool of employees and further influences voice behavior (Halbesleben et al., Reference Halbesleben, Neveu, Paustian-Underdahl and Westman2014; Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001). When territoriality is low, fewer territorial behaviors reserve more resources for employees, so employees tend to invest in actions such as voice behavior. When territoriality changes from low to moderate, many territorial behaviors consume more resources (Brown, Lawrence, & Robinson, Reference Brown, Lawrence and Robinson2005). Therefore, employees with fewer resources will be more vulnerable to investment behaviors and inclined to conservation behavior. That is, they will reduce voice behavior. When territoriality changes from moderate to high, the formed territorial pattern does not induce more territorial behaviors from employees, thus reserving more resources to help employees invest in an action such as voice behavior. Therefore, based on the above argument, territoriality has a U-shaped influence on voice behavior, including promotive and prohibitive voices. Consequently, we formulated the hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis 3: Territoriality curvilinearly mediates the relationship of POP on promotive voice (H3a)/prohibitive voice (H3b). Specifically, POP was positively associated with territoriality, and territoriality has a U-shaped influence on promotive voice/prohibitive voice.

Method

Participants and procedures

Data were collected from March to June 2019. The participants, recruited through a course program where they were studying for an MBA at a university in southwest China, were free to decide whether to participate and advised that this task would not be included as part of the course grade. We also explained that the purpose of the study was to explore the effects of a challenging work environment on work behavior. We left the contact details of the research team so that they could contact us if they were interested in the topic. Participants were full-time employees from various industries and occupations, including R&D, marketing, finance and accounting, administration, production and logistics, etc. In this study, to control for common method biases, the questionnaire survey was administered in three stages with a two-week interval between each stage. The first stage collected the demographic information (gender, age, and organizational tenure) of the respondents and measured the independent (i.e., POP) and control (i.e., zhongyong) variables. The second stage measured the mediating variable (i.e., territoriality), while the third stage measured the dependent variables (i.e., promotive voice and prohibitive voice).

The questionnaires were anonymous; however, respondents were reminded to provide their phone number each time they filled out the questionnaire. The phone number helps respondents receive a telephone recharge of 10 CNY (approximately $ 1.5) as a reward for each survey and also served as a tag to match the three-stage measurement. To encourage respondents to complete all three surveys, we informed them at the start of the survey that they would receive an extra 10 CNY in phone recharge fees as a reward if they completed all stages of the survey.

In the first stage, we distributed 409 questionnaires to the participants. After excluding some unqualified questionnaires, such as those with missing data, 332 qualified questionnaires were obtained (qualified rate was 81%), In the second stage, we distributed 332 questionnaires to the remaining respondents. After matching and eliminating unqualified questionnaires, 274 qualified questionnaires were obtained (qualified rate was 83%). In the third stage, we distributed 274 questionnaires to the remaining respondents. After matching and eliminating the unqualified questionnaires, 227 qualified questionnaires were obtained (qualified rate was 83%). The final effective response rate of the three-wave survey was 56%. Among the respondents in the final sample, 53% were male; their average age was 32.3 years, and their average organizational tenure was 6.1 years.

Measures

All variables were administered using a 5-point Likert scale, except for those three demographic variables, where 1 represents strongly disagree and 5 represents strongly agree. All scales were translated into Chinese in accordance with translation and back-translation procedures (Brislin, Reference Brislin, Triandis and Berry1980).

Perceived organizational politics

Vigoda (Reference Vigoda2001) 6-item scale was used to measure POP at Time 1. A sample item was ‘People in this organization attempt to build themselves up by tearing others down.’ The reliability value of the scale was .89.

Territoriality

Avey et al., (Reference Avey, Avolio, Crossley and Luthans2009) 4-item scale was used to measure territoriality at Time 2. A sample item was ‘I feel that people I work with in my organization should not invade my workspace.’ The reliability value of the scale was .75.

Promotive voice and prohibitive voice

Liang, Farh, and Farh (Reference Liang, Farh and Farh2012) 10-item scale was used to measure voice at Time 3. There were 5 items related to promotive/prohibitive voice, respectively. ‘I raise suggestions to improve the unit's working procedure’ represents an item of promotive voice scale. ‘I dare to voice out opinions on things that might affect efficiency in the work unit, even if that would embarrass others’ represents an item of prohibitive voice scale. The reliability value of promotive voice scale was .91, and prohibitive voice was .90.

Controls

First, like other voice behavior studies (Li, Liang, & Farh, Reference Li, Liang and Farh2020; Ng & Lucianetti, Reference Ng and Lucianetti2018), age, gender, and organizational tenure were controlled in this study. Second, considering that (1) cultural factors may influence the sample data and further affect the findings, and (2) several studies found that zhongyong is related to employee voice (Duan & Ling, Reference Duan and Ling2011; Qu, Wu, Tang, Si, & Xia, Reference Qu, Wu, Tang, Si and Xia2018), this typical Chinese cultural factor was also regarded as a control variable. Zhongyong – a neutral and balanced value system based on holistic perception – is one of the core tenets of Confucianism. It emphasizes thinking and solving problems from the perspective of the whole, striving to find the appropriate point between the two ends and promoting the development of the whole while affirming the principles and nature of affairs (Chang & Yang, Reference Chang and Yang2014; Liu, Zhou, & Sheng, Reference Liu, Zhou and Sheng2021; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Zhang, Zhao, Zhao, Wang, Chen and Zhang2016). It was measured using Du, Ran, and Cao (Reference Du, Ran and Cao2014) 6-item scale at Time 1. ‘When making decisions, I will adjust myself for the overall harmony’ represents an item of the scale. The reliability value of the scale was .80.

Analytical approach

First, since the data in this research are from the same respondents, it could lead to common method deviation, thus affecting the research results. Therefore, Harman's single factor analysis is used to verify whether there is common method deviation in our sample (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). Second, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to verify the validity of the model variables, with Mplus 8.0 (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2017). Last, consistent with previous studies (Ete et al., Reference Ete, Sosik, Cheong, Chun, Zhu, Arenas and Scherer2020; Haldorai, Kim, & Phetvaroon, Reference Haldorai, Kim and Phetvaroon2022; Lin, Law, & Zhou, Reference Lin, Law and Zhou2017; Solberg, Lai, & Dysvik, Reference Solberg, Lai and Dysvik2021), we used the MEDCURVE macro (Hayes & Preacher, Reference Hayes and Preacher2010) to verify the hypotheses, wherein a bootstrapping approach with 5000 iterations was used (Edwards & Lambert, Reference Edwards and Lambert2007). The MEDCURVE macro is specifically designed to examine ‘instantaneous indirect effects’ (θ) in curvilinear mediations. The curvilinear mediation is considered statistically significant if the 95% confidence interval (CI) does not include .

Results

Common method variance

Harman's single factor test indicated that all items could be grouped into five factors, and the first factor explained only 26% of the variance. Therefore, there is no obvious problem of common method deviation in this study.

Confirmatory factor analyses

CFA results exhibited that the expected five-factor model was best fit the data (χ2/df = 1.59, CFI = .94, TLI = .94, RMSEA = .05). From Table 1, we can see that the other validated models have worse data fit than our hypothesized model. These results imply that the variables of the conceptual model are different.

Table 1. Results of confirmatory factor analysis

a Perceived organizational politics, zhongyong, territoriality, promotive voice, prohibitive voice.

b Combining promotive voice and prohibitive voice.

c Combining perceived organizational politics and zhongyong.

d Combining perceived organizational politics and zhongyong, combining promotive voice and prohibitive voice;

e Combining all variables.

N = 227.

Descriptive statistics and correlations

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics and correlations of all studied variables. POP was positively correlated with territoriality (r = .22, p < .01), and negatively correlated with promotive voice (r = −.27, p < .001) and prohibitive voice (r = −.35, p < .001). Territoriality was not correlated with either promotive voice (r = .04, ns) or prohibitive voice (r = .00, ns).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and correlations

Notes: N = 227. POP = perceived organizational politics, reliabilities coefficients are on the diagonal. Age and tenure measured in years. Gender 1 = male, 2 = female.

M mean, SD standard deviation. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Hypotheses testing

Table 3 illustrates that, after controlling for the effects of gender, age, organizational tenure, and zhongyong, POP was positively associated with territoriality (B = .17, p < .01). This supported Hypothesis 1.

Table 3. Regression analyses

POP, perceived organizational politics.

N = 227.

a Based on bootstrap 5,000.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Hypothesis 2 stated that territoriality has U-shaped relationships with promotive/prohibitive voice. Table 3 depicts, for promotive voice and prohibitive voice, the squared territoriality terms were significant and positive (B = .17, SE = .05, p < .001 and B = .17, SE = .06, p < .01, respectively), suggesting that when territoriality was low and high, there was more promotive/prohibitive voice behavior; when territoriality was moderate, there was less promotive/prohibitive voice behavior. As shown in Figures 2 and 3, the shape of the graph for territoriality and promotive/prohibitive voice behavior supported Hypotheses 2a and 2b, with inflection points of 2.88. That is, when territoriality is lower than 2.88, promotive/prohibitive voice gradually decreases, and when it is higher than 2.88, promotive/prohibitive voice gradually increases.

Fig. 2. U-shaped relationship between territoriality and promotive voice.

Fig. 3. U-shaped relationship between territoriality and prohibitive voice.

The curvilinear mediation effect of territoriality is a linear function of territoriality. According to MEDCURVE macro approach, to test the curvilinear mediating effect, we could calculate three instantaneous indirect effects (θ) at three typical levels of territoriality (that is, M – 1SD, M, and M + 1SD). If θ is not statistically equal to 0, territoriality curvilinearly mediates the relationship of POP on voice behavior. From Table 3, the bootstrapping analysis (5,000 samples) with bias-corrected confidence intervals revealed that, for promotive voice, when territoriality was low, moderate, and high, the instantaneous indirect effects were positive and significant (θ = .02, SE = .01, 95% CI [.00–.05]; θ = .03, SE = .02, 95% CI [.01–.07]; θ = .04, SE = .02, 95% CI [.01–.09], respectively). As the instantaneous indirect effects do not include 0, Hypothesis 3a was supported.

Similarly, for prohibitive voice, the instantaneous indirect effects were still positive and significant (θ = .02, SE = .01, 95% CI [.01–.06]; θ = .03, SE = .01, 95% CI [.01–.07] and θ = .04, SE = .02, 95% CI [.01–.09], respectively). As the instantaneous indirect effects do not include 0, Hypothesis 3b was supported, too.

Discussion

This study endeavored to investigate the mechanism of POP on voice behavior, using territoriality as a mediator. From a COR perspective, using a three-wave survey, we demonstrated that POP was curvilinearly and indirectly related to voice behavior via the positive linear relationship of POP on territoriality, and territoriality's U-shaped relationships with both promotive voice and prohibitive voice.

Theoretical implications

This study has several theoretical implications. First, previous studies argued that POP was negatively related to voice (Bergeron & Thompson, Reference Bergeron and Thompson2020; Li et al., Reference Li, Wu, Liu, Kwan and Liu2014, Reference Li, Liang and Farh2020). This study found a U-shaped relationship between them, allowing us to understand the POP-voice linkage more comprehensively. When POP is low and high, it can promote employee voice behavior through territoriality, implying that POP is not necessarily destructive and detrimental but can entail some beneficial additions (Landells & Albrecht, Reference Landells and Albrecht2017). This may be explained as, in a high-POP environment, although there are interest groups, they are relatively stable and the pattern is set, so that employees' investment behaviors, such as voice behavior, increase. Additionally, based on previous studies, the target of voice behavior can be supervisors, colleagues, or even people outside the organization, and the underlying motivation of voice behavior may be prosocial, or for one's own interests (Morrison, Reference Morrison2014). Here, it is likely that the employees' voice behavior in high-POP environments are mainly targeted and functional to specific groups/powers rather than the organization as a whole. Generally, these findings reinforce the evidence in a POP-voice linkage, allowing a more comprehensive and deeper understanding of the impact of POP, a common organizational environment, on voice behavior.

Second, the U-shaped relationship between territoriality and voice behavior gives us a new understanding of territoriality. Although it is defensive-oriented, it can also lead to organization-friendly behavior. Previous research has generally suggested territoriality stimulates negative work behaviors, such as knowledge hiding (Huo et al., Reference Huo, Cai, Luo, Men and Jia2016; Peng, Reference Peng2013). However, based on COR theory, this study argues that when territoriality is high, employees will enhance investment behaviors such as voice behavior. As far as we know, this study is one of the few empirical studies that demonstrates the opposite side of territoriality, namely, that it can also have beneficial by-products for organizations, such as voice behavior. Thus, it enriches the literature on territoriality's outcome and provides strong empirical evidence to support Avey et al. (Reference Avey, Avolio, Crossley and Luthans2009) perspective that ‘even territorial psychological ownership with its typically negative connotation may have a positive side.’

Third, we clarified that territoriality could serve as an explanation mechanism for the POP-voice relationship, elucidating why there is a U-shaped relationship between POP and voice behavior. To the best of our knowledge, although some studies have found a U-shaped relationship between POP and some work outcomes, such as Hochwarter et al. (Reference Hochwarter, Ferris, Laird, Treadway and Gallagher2010) study on POP-job satisfaction/job tension, its internal mechanism is not yet clear. Based on the COR perspective, this research takes territoriality as the intermediary to explain the curvilinear transmission effect of POP on voice through the positive linear relationship of POP on territoriality and territoriality's U-shaped relationship with voice behavior. The results show that POP does not always block voice behavior. When the territoriality facilitated by POP creates a stable pattern in an organization, it simplifies relationships and reduces conflict between employees, who become more willing to implement voice behavior (Brown, Lawrence, & Robinson, Reference Brown, Lawrence and Robinson2005). This can also help us understand why voice behavior is considered an investment behavior when POP is very high.

Practical implications

Here are some applications for practitioners. First, although at both low and high levels of POP, employees tend to increase the use of their voices, compared with low-level POP, high-level POP will bring many other adverse work outcomes, such as increased strain, burnout, turnover intentions, and decreased affective commitment (see the meta-analysis of Bedi and Schat (Reference Bedi and Schat2013) and Chang, Rosen, and Levy (Reference Chang, Rosen and Levy2009)). Therefore, organizations should periodically and systematically assess their organizational political climates and try to find ways to reduce POP. For example, they should promote the standardization and formalization of their evaluation systems (e.g., reward, promotion), which can reduce ambiguity and uncertainty, thus reducing manipulation (i.e., self-service behavior; Jarrett, Reference Jarrett2017). Additionally, organizations should strive to strengthen cohesion, develop a sharing atmosphere, and reduce the number of self-serving groups, so as to enhance the collective consciousness of their employees.

Second, although high and low territoriality brings more voice behavior, the defensive attribute accompanied by high territoriality will lead to some bad outcomes for the organization, such as increased knowledge hiding and decreased invited creativity (feedback giver's creativity) (Brown & Baer, Reference Brown and Baer2015; Peng, Reference Peng2013). Therefore, taken together, organizations should try to reduce territoriality. Organizations can vigorously advocate the concept of ‘we are one family’ to break down the boundaries between departments and teams, strengthen the concept of ‘ours’ and weaken the concept of ‘mine’ (Huo et al., Reference Huo, Cai, Luo, Men and Jia2016). Organizations can also organize more interactive activities and redesign jobs to make them more interdependent, thus pushing employees into a low-territoriality state.

Limitations and future directions

Admittedly, this research also has limitations. First, common method biases may exist in our study since we used the same source of measurements, although we employed a three-stage investigation to attenuate this contamination, and Harman's single factor test also indicated that there was no obvious common method deviation. Thus, to ensure the robustness of research results, future studies can utilize multiple sources of data such as collected voice behavior from supervisors. Second, there may be other explanations for the relationship between the variables studied in this study. For example, territoriality may encourage employees to adopt political behaviors to strategically influence others to protect their own territories, thereby increasing POP. Therefore, further experimental or longitudinal studies should be conducted in the future to provide better evidence for the causal relationship between the variables in our model. Third, this research only demonstrated the intermediary mechanism of POP-voice linkage, without considering the boundary conditions of the relationships among the variables. Future research can consider boundary conditions, such as personality characteristics, to improve the conceptual model. Fourth, our study did not control for the levels of each studied variable at different times, i.e., we do not account for autoregressive relations and changes in these variables. Future studies may consider measuring all study variables at each time point to more accurately verify the relationship between variables.

Conclusion

This research aimed to investigate the internal mechanism of POP on employee voice behavior from a COR perspective. We found that POP is positively associated with territoriality, and territoriality was U-shaped related to promotive/prohibitive voice. Further, the results showed that territoriality acts as a curvilinear mediator for POP-voice linkage. Future research should extend these findings to examine the relationships among POP, territoriality, and other work outcomes such as knowledge hiding and creativity.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all individual participants included in the study.

Financial support

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number 71872119) and Sichuan University (2022CX20).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Hao Zhou is a professor at Business School of Sichuan University, in China. His research interests include extra-role behavior and leadership.

Qin Liu is a doctoral student at the Business School of Sichuan University, in China. Her research interests include voice behavior, leadership and organizational politics.