No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

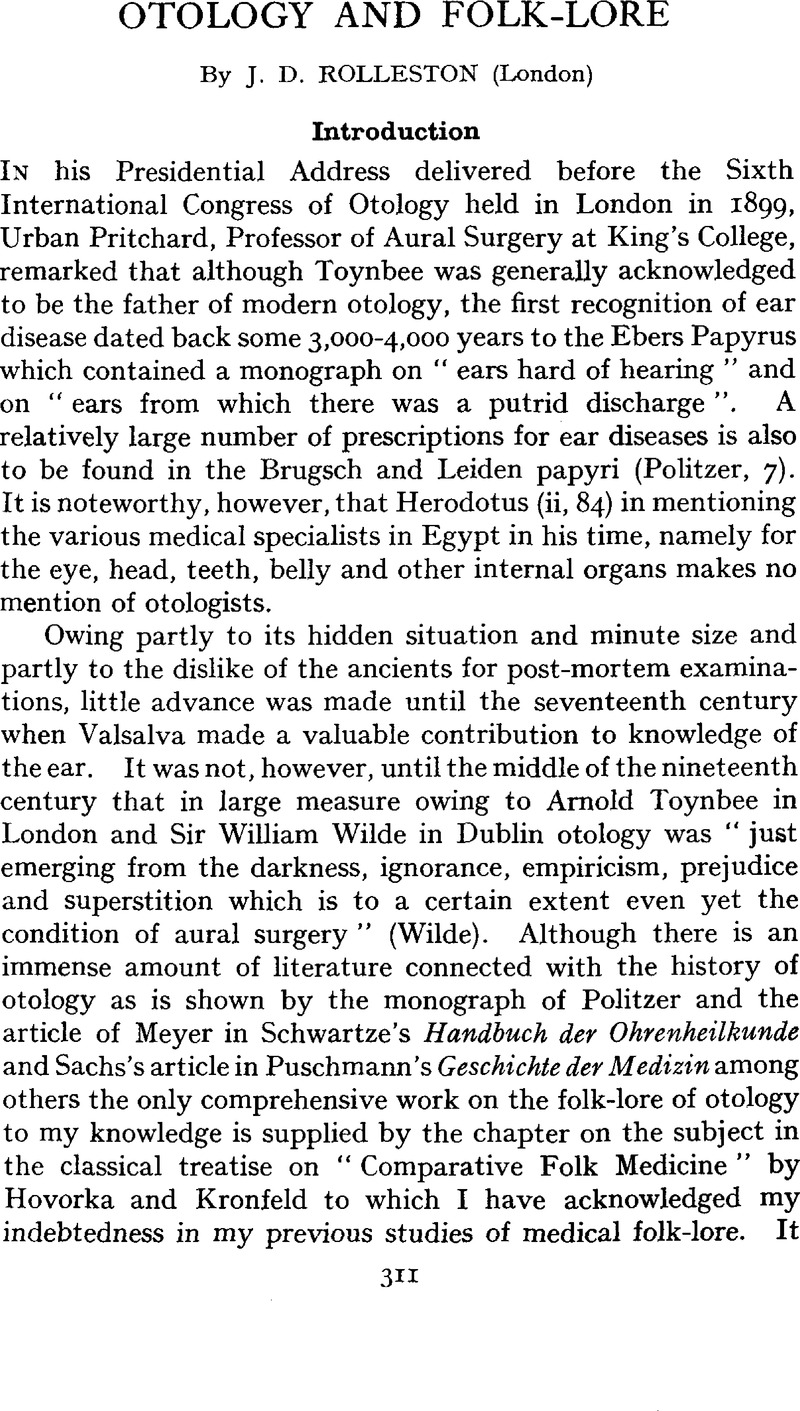

Otology and Folk-Lore

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 08 April 2017

Abstract

An abstract is not available for this content so a preview has been provided. Please use the Get access link above for information on how to access this content.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © JLO (1984) Limited 1942

References

Bergen, F., “Current superstitions collected from the tradition of English-speaking people,” 1896.Google Scholar

Du Broc de, Segagne L., “Les saints patrons des corporations et protecteures spécialement invoqués dans les maladies et dans les circumstances critiques de la vie,” 1887.Google Scholar

Napier, J., “Folk-lore and superstitious beliefs in the West of Scotland within this century,” 1879, 72.Google Scholar