Impact statement

Young people have an increased vulnerability to mental health conditions, and those living in low- and middle-income countries face disproportionate barriers in accessing high quality mental health care. Given increasing digital connectivity in the global south, digital mental health interventions (DMHIs) show promise in improving mental health outcomes for these populations by circumventing key barriers to care. In this systematic review, we evaluate the quality and availability of evidence on the effectiveness of DMHIs for young people and use this to provide evidence-based policy recommendations to improve youth mental health outcomes. Our findings show evidence of the effectiveness of multiple forms of DMHI (especially internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy) on anxiety and depression outcomes. At the same time, our results show a lack of high-quality studies on the topic, characterised by high dropout rates, small sample sizes and insufficient data on the statistical significance of treatment effects and long-term benefits of treatment. Our findings highlight that DMHIs have the potential to improve youth mental health outcomes in these settings but given the lack of robust data, increased adoption of these technologies would require further research on the topic.

Introduction

Young people (YP) make up around a quarter (1.8 billion) of the world’s population, with almost 90% living in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where they constitute up to 50% of the population (UNFPA, 2014). YP, defined as those aged 10–24 by the World Health Organisation (WHO), are disproportionately affected by mental health issues (WHO, 2024). Around 50% of mental health conditions start by age 14, and 75% by age 24, and around 1 in 5 adolescents experience a mental health condition each year (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas and Walters2005), resulting in over 250 million YP globally having a mental health disorder (IHME, 2023). The Covid-19 pandemic and associated lockdowns have further exacerbated this burden (Racine et al., Reference Racine, McArthur, Cooke, Eirich, Zhu and Madigan2021).

YP are especially vulnerable to mental health problems due to exposure to physical, emotional and social risk factors, such as pressure from peers to conform, exploration of identity, stigma, discrimination, lack of access to quality mental health services, poverty, abuse and violence (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Flisher, Hetrick and McGorry2007; WHO, 2020). Unfortunately, most mental illnesses among YP remain undiagnosed and untreated due to barriers to accessing and seeking care (Lehtimaki et al., Reference Lehtimaki, Martic, Wahl, Foster and Schwalbe2021; UNICEF, 2021). YP in LMICs are disproportionately affected by this burden, due to fragmented and lower-resourced healthcare systems, poverty, stigma, lack of government policy, inadequate funding and a paucity of trained clinicians (Kieling et al., Reference Kieling, Baker-Henningham, Belfer, Conti, Ertem, Omigbodun, Rohde, Srinath, Ulkuer and Rahman2011; Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Pinninti, Irfan, Gorczynski, Rathod, Gega and Naeem2017; Wainberg et al., Reference Wainberg, Scorza, Shultz, Helpman, Mootz, Johnson, Neria, Bradford, Oquendo and Arbuckle2017). The mental health treatment gap, defined as the difference between the number of people who need care and those who receive it (Jansen et al., Reference Jansen, White, Hogwood, Jansen, Gishoma, Mukamana and Richters2015), is particularly significant for YP in LMICs, reaching rates of up to 90% (The WHO World Mental Health Survey Consortium, 2004; Duarte et al., Reference Duarte, Lovero, Sourander, Ribeiro and Bordin2022).

Digital mental health interventions (DMHIs), defined as ‘information, support and therapy for mental health conditions delivered through an electronic medium with the aim of treating, alleviating or managing (mental health) symptoms’ (Torous et al., Reference Torous, Bucci, Bell, Kessing, Faurholt‐Jepsen, Whelan, Carvalho, Keshavan, Linardon and Firth2021), are a viable alternative to face-to-face mental healthcare. These interventions can be delivered via multiple platforms, such as smartphone apps, online programmes, text messaging, telepsychiatry and wearable devices such as smart watches (Carter et al., Reference Carter, Araya, Anjur, Deng and Naslund2021). Although YP living in LMICs have limited access to mental healthcare, many have access to digital technologies (WHO, 2020), at increasingly younger ages (Kardefelt Winther et al., Reference Kardefelt Winther, Livingstone and Saeed2019). Given that wireless connectivity in LMICs is becoming more widely available (The World Bank, 2024), and that smartphones are becoming cheaper, people in LMICs are increasingly able to access the internet (Kemp, Reference Kemp2020), making DMHIs a feasible solution to this treatment gap.

Effective DMHIs have the potential to help address the global inequality in the provision of mental health services, providing greater accessibility, acceptability, affordability, confidentiality and flexibility, leading to improved access to care (Wallin et al., Reference Wallin, Mattsson and Olsson2016). By meeting the WHO criteria for YP-friendly interventions, namely availability, accessibility, equitability (e.g., non-judgmental care), acceptability (e.g., provision of confidential and youth-centred care) and appropriateness (Mazur et al., Reference Mazur, Brindis and Decker2018), DMHIs can improve YP’s empowerment, participation and help-seeking behaviours (Shortliffe, Reference Shortliffe2016). Additionally, they could counter mental health stigma and provide safe and confidential care in cases where YP may fear social isolation or other inhumane responses to their mental illness (Semrau et al., Reference Semrau, Evans-Lacko, Koschorke, Ashenafi and Thornicroft2015).

Despite their potential, there is limited research on DMHIs in LMICs, potentially due to researchers and clinicians prioritising clinical care over research output in resource-scarce healthcare systems (Kar et al., Reference Kar, Oyetunji, Prakash, Ogunmola, Tripathy, Lawal, Sanusi and Arafat2020; Lehtimaki et al., Reference Lehtimaki, Martic, Wahl, Foster and Schwalbe2021). Additionally, there is a lack of governance and regulation over the use of DMHIs to improve YP’s mental health in LMICs (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Marais, Abdulmalik, Ahuja, Alem, Chisholm, Egbe, Gureje, Hanlon, Lund, Shidhaye, Jordans, Kigozi, Mugisha, Upadhaya and Thornicroft2017). These barriers may prevent the development, implementation and evaluation of such interventions in LMICs.

Until recently, DMHIs have mainly been developed for and used in high-income countries (HICs), where they have been found to be effective at reducing symptoms of mental health conditions such as depression (Firth et al., Reference Firth, Torous, Nicholas, Carney, Pratap, Rosenbaum and Sarris2017), psychosis (Gire et al., Reference Gire, Farooq, Naeem, Duxbury, McKeown, Kundi, Chaudhry and Husain2017) and other severe mental illnesses (Naslund et al., Reference Naslund, Marsch, McHugo and Bartels2015), while also improving medication adherence (Rootes-Murdy et al., Reference Rootes-Murdy, Glazer, Van Wert, Mondimore and Zandi2018). Evidence of their effectiveness in LMICs is scarce (Larsen et al., Reference Larsen, Huckvale, Nicholas, Torous, Birrell, Li and Reda2019), limiting their applicability in these settings (Henrich et al., Reference Henrich, Heine and Norenzayan2010). To understand opportunities for DMHIs for YP in LMICs, it is therefore essential to examine studies from these settings (Carter et al., Reference Carter, Araya, Anjur, Deng and Naslund2021), given the under-prioritisation of mental health research (Becker and Kleinman, Reference Becker and Kleinman2013) and the lack of governance and regulation around DMHIs (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Marais, Abdulmalik, Ahuja, Alem, Chisholm, Egbe, Gureje, Hanlon, Lund, Shidhaye, Jordans, Kigozi, Mugisha, Upadhaya and Thornicroft2017).

Aims and objectives

To respond to the opportunities offered by DMHIs for YP in LMICs, comprehensive identification and assessment of the available evidence base is required. However, no literature reviews were found investigating this topic. Therefore, the overall aim of this review is to examine the evidence for DMHIs for treating mental disorders in YP in LMICs.

The specific objectives of the review are to:

-

1. Evaluate the clinical effectiveness of DMHIs on mental health symptoms for YP in LMICs.

-

2. Assess the availability and quality of the current evidence on DMHIs focusing on YP’s mental health outcomes based in LMICs.

-

3. Provide practice and research recommendations for the use of DMHIs focusing on YP’s mental health outcomes based in LMICs.

Methods

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting criteria were followed (Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff, Akl, Brennan, Chou, Glanville, Grimshaw, Hróbjartsson, Lalu, Li, Loder, Mayo-Wilson, McDonald, McGuinnnes, Stewart, Thomas, Tricco, Welch, Whiting and Moher2021).

Eligibility criteria

Eligibility criteria for this study (Table 1) were based on a modified version of the Population, Intervention, Control, Outcome framework (CRD, 2009; Methley et al., Reference Methley, Campbell, Chew-Graham, McNally and Cheraghi-Sohi2014).

Table 1. Eligibility criteria for studies

Abbreviations: DMHI, Digital Mental Health Intervention; GAD-7, general anxiety disorder-7; HICs, high income countries; ICD-11, international classification of diseases 11th revision; LMIC, low- and middle-income country; PHQ-9, patient health questionnaire-9; YP, young people.

Search strategy and selection criteria

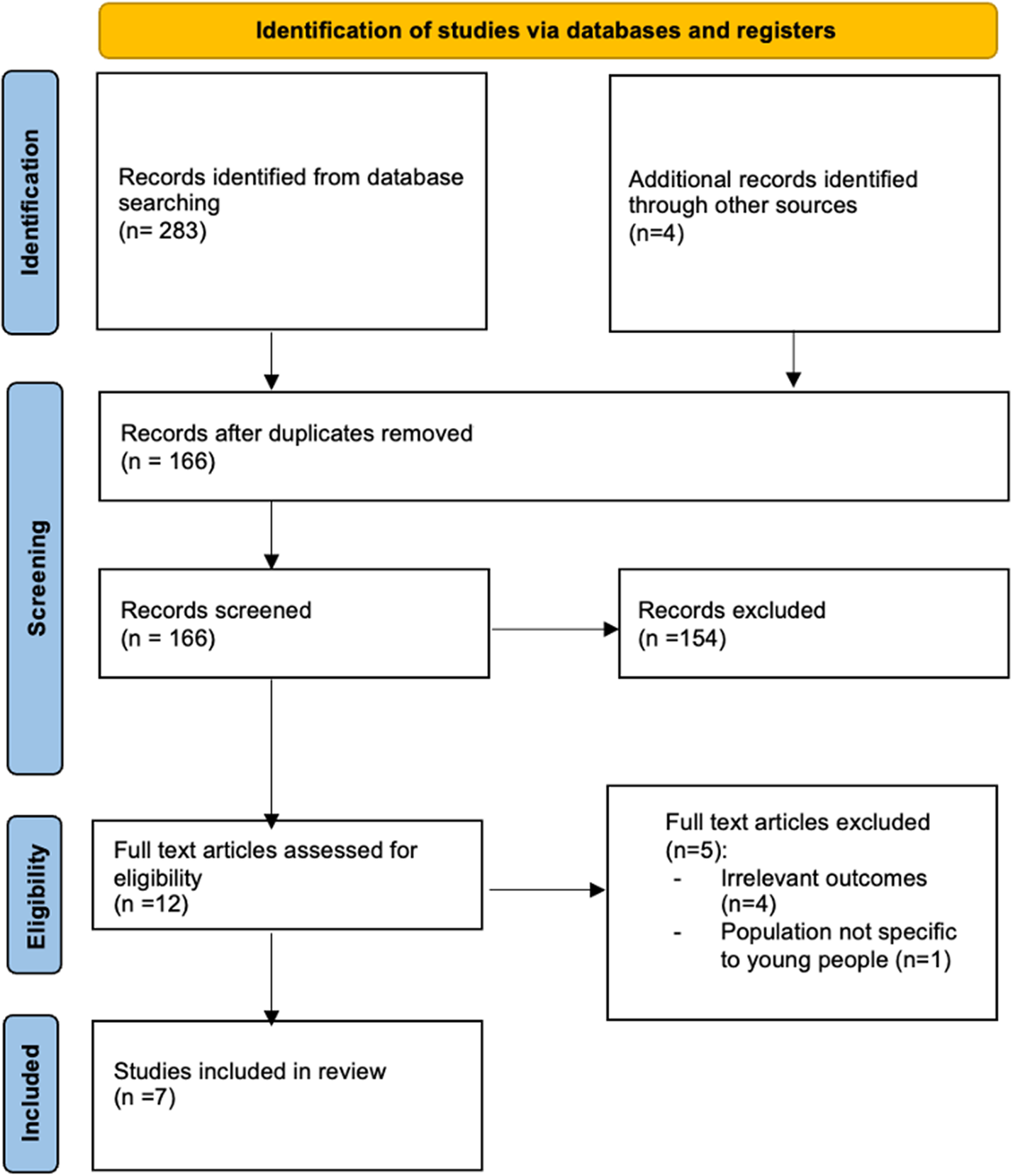

The review was conducted using a predefined protocol based on the PRISMA reporting criteria (Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff, Akl, Brennan, Chou, Glanville, Grimshaw, Hróbjartsson, Lalu, Li, Loder, Mayo-Wilson, McDonald, McGuinnnes, Stewart, Thomas, Tricco, Welch, Whiting and Moher2021), with key stages being identification, screening, assessing eligibility and inclusion of studies (Figure 1). JA conducted an electronic review of the literature from the MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science and PsycINFO databases, based on recommendations from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) library staff (Table 2). DC re-ran all the searches as the second reviewer to minimise bias. JA and DC also hand-searched reference lists of all identified full text studies to manually identify relevant publications.

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart.

Table 2. Number of articles found

The authors used a combination of keywords such as (“digital,” “mHealth,” “eHealth,” “web-based,” “internet-based,” “mobile phone,” “text message,” “SMS,” “artificial intelligence”) AND (“adolescen*,” “youth” “young,” “child,” “student”) AND (“mental health,” “wellbeing”). An LMIC filter was used to select relevant studies. For a full list of search terms, please see Supplementary Material S1.

Identified references were screened by JA by conducting an abstract and title search based upon the eligibility criteria (Table 1). Full texts were assessed for final inclusion by JA. This process was repeated by the second reviewer (DC), reaching the same conclusions.

Data extraction

JA extracted data from the studies, using a data extraction form (Table 3). Data were collected on the study context; population group; outcome(s) of interest; methods (sample size, study design, intervention type, control group, theoretical approach); targets (inclusion/exclusion criteria, participant characteristics); intervention (mental health issues addressed, technological approaches used, study setting, number of sessions, content, presence of mental health support) and impacts (evaluation methods, primary/secondary outcome measures and key findings).

Table 3. Included studies

Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; BDI-II, Beck’s Depression Inventory; CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; CES-D, centre for epidemiologic studies depression scale; DASS, depression anxiety and stress scale; DMHI, Digital Mental Health Intervention; GAD, generalised anxiety disorder; GAD-7, general anxiety disorder-7; GAD-Q-IV, generalised anxiety disorder questionnaire IV; HICs, high income countries; iCBT, internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy; ICD-11, international classification of diseases 11th revision; ITT, intention-to-treat analysis; LMIC, low- and middle-income country; MBI, mindfulness based intervention; mHealth, mobile health; PHQ-8, patient health questionnaire-8; PHQ-9, patient health questionnaire-9; PSWQ, Penn State Worry Questionnaire; RCT, randomised control trial; WEMWBS, Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale; YP, young people.

As only randomised control trials (RCTs) were identified, JA used Critical Appraisal Skills Programme’s (CASP’s) RCT criteria as a validated quality assessment framework to appraise the quality of identified studies (see Supplementary Material S2) (CASP, 2020). CASP was selected over other assessment tools as it focuses on study validity, results and clinical relevance, which align with the review’s objectives (CASP, 2020). We utilised Vogel’s (Reference Vogel2013) criteria to evaluate the quality of studies, categorising them as high, medium or low quality. Although we initially planned to exclude any study identified as “low quality,” none met this criterion upon evaluation. Consequently, all studies were included in the analysis.

Data synthesis

A descriptive analysis was conducted, based on the study objectives. Due to the expected heterogeneity of the included interventions, outcome types, measures and study designs, a quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis) of the findings was not deemed appropriate. JA therefore synthesised evidence from the articles describing the clinical effectiveness of DMHIs using a narrative synthesis approach.

Results

Selection of included studies

The initial search yielded 283 results. After excluding duplicate references, the number of articles was reduced to 166. The manual search yielded an additional four articles for eligibility assessment. A total of seven articles were finally included (Wannachaiyakul et al., Reference Wannachaiyakul, Thapinta, Sethabouppha, Thungjaroenkul and Likhitsathian2017; Moeini et al., Reference Moeini, Bashirian, Soltanian, Ghaleiha and Taheri2019; Ofoegbu et al., Reference Ofoegbu, Asogwa, Otu, Ibenegbu, Muhammed and Eze2020; Osborn et al., Reference Osborn, Rodriguez, Wasil, Venturo-Conerly, Gan, Alemu, Roe, Arango, Otieno, Wasanga, Shingleton and Weisz2020; Salamanca-Sanabria et al., Reference Salamanca-Sanabria, Richards, Timulak, Connell, Mojica Perilla, Parra-Villa and Castro-Camacho2020; Newman et al., Reference Newman, Kanuri, Rackoff, Jacobson, Bell and Taylor2021; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Lin, Goldberg, Shen, Chen, Qiao, Brewer, Loucks and Operario2022) (see Figure 1 for PRISMA flowchart [Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff, Akl, Brennan, Chou, Glanville, Grimshaw, Hróbjartsson, Lalu, Li, Loder, Mayo-Wilson, McDonald, McGuinnnes, Stewart, Thomas, Tricco, Welch, Whiting and Moher2021]).

Characteristics of included studies

Details of the final seven eligible studies are provided in Table 3. The studies were all conducted between the years 2017 and 2022 in five geographic regions (Africa n = 2, Southeast Asia n = 2, South Asia n = 1, South America n = 1, Middle East n = 1). The mean age of participants varied from 16.2 (Moeini et al., Reference Moeini, Bashirian, Soltanian, Ghaleiha and Taheri2019) to 24.21 years (Ofoegbu et al., Reference Ofoegbu, Asogwa, Otu, Ibenegbu, Muhammed and Eze2020). Several studies were based in universities (Ofoegbu et al., Reference Ofoegbu, Asogwa, Otu, Ibenegbu, Muhammed and Eze2020; Salamanca-Sanabria et al., Reference Salamanca-Sanabria, Richards, Timulak, Connell, Mojica Perilla, Parra-Villa and Castro-Camacho2020; Newman et al., Reference Newman, Kanuri, Rackoff, Jacobson, Bell and Taylor2021; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Lin, Goldberg, Shen, Chen, Qiao, Brewer, Loucks and Operario2022); however, other settings such as schools (Moeini et al., Reference Moeini, Bashirian, Soltanian, Ghaleiha and Taheri2019), high schools (Osborn et al., Reference Osborn, Rodriguez, Wasil, Venturo-Conerly, Gan, Alemu, Roe, Arango, Otieno, Wasanga, Shingleton and Weisz2020) and a youth detention centre (Wannachaiyakul et al., Reference Wannachaiyakul, Thapinta, Sethabouppha, Thungjaroenkul and Likhitsathian2017) were also studied. All studies used a RCT design. Three studies were specifically focused on depression, and four studies on depression and anxiety. Notably, no studies were found evaluating DMHIs focussed on any other psychopathology. All but one study only included participants with mild–moderate symptoms, excluding those with severe symptoms or comorbidities.

Studies used different theoretical concepts to underpin interventions, such as mindfulness (n = 1), cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT; n = 5) and social cognitive theory (n = 1) All reviewed interventions were accessible from mobile devices or computers and used internet-based platforms, except for a computerised platform evaluated by Wannachaiyakul et al. (Reference Wannachaiyakul, Thapinta, Sethabouppha, Thungjaroenkul and Likhitsathian2017). All identified interventions also involved either new content and/or adaptations of existing evidence-based psychosocial treatments. For example, Salamanca-Sanabria et al. (Reference Salamanca-Sanabria, Richards, Timulak, Connell, Mojica Perilla, Parra-Villa and Castro-Camacho2020) culturally adapted an existing programme to create a Colombian version of internet-based CBT (iCBT), while Sun et al. (Reference Sun, Lin, Goldberg, Shen, Chen, Qiao, Brewer, Loucks and Operario2022) used a popular Chinese social media platform (WeChat) to deliver a mindfulness intervention. Digital interventions included a range of content (e.g., challenging core beliefs, increasing knowledge about mental health, value affirmation exercises) using a range of multimedia options (e.g., videos, animations, presentations). All interventions were externally guided or supported. The interventions lasted between a single session (Osborn et al., Reference Osborn, Rodriguez, Wasil, Venturo-Conerly, Gan, Alemu, Roe, Arango, Otieno, Wasanga, Shingleton and Weisz2020) and 6 months (Moeini et al., Reference Moeini, Bashirian, Soltanian, Ghaleiha and Taheri2019). Dropout rates in the intervention group ranged from 9% (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Lin, Goldberg, Shen, Chen, Qiao, Brewer, Loucks and Operario2022) to 91% (Salamanca-Sanabria et al., Reference Salamanca-Sanabria, Richards, Timulak, Connell, Mojica Perilla, Parra-Villa and Castro-Camacho2020). Two studies (Wannachaiyakul et al., Reference Wannachaiyakul, Thapinta, Sethabouppha, Thungjaroenkul and Likhitsathian2017; Osborn et al., Reference Osborn, Rodriguez, Wasil, Venturo-Conerly, Gan, Alemu, Roe, Arango, Otieno, Wasanga, Shingleton and Weisz2020) had no loss to follow-up. No studies reported on the cost-effectiveness or design elements of DMHIs.

Studies were found to have selection bias through loss to follow-up (e.g., Moeini et al., Reference Moeini, Bashirian, Soltanian, Ghaleiha and Taheri2019 reported a 30% drop out rate in the intervention group), and recruitment via self-selection (e.g., Osborn et al., Reference Osborn, Rodriguez, Wasil, Venturo-Conerly, Gan, Alemu, Roe, Arango, Otieno, Wasanga, Shingleton and Weisz2020 recruited all students who were interested in the study). Only three studies (Wannachaiyakul et al., Reference Wannachaiyakul, Thapinta, Sethabouppha, Thungjaroenkul and Likhitsathian2017; Moeini et al., Reference Moeini, Bashirian, Soltanian, Ghaleiha and Taheri2019; Newman et al., Reference Newman, Kanuri, Rackoff, Jacobson, Bell and Taylor2021) reported sample size calculations, and six studies (Wannachaiyakul et al., Reference Wannachaiyakul, Thapinta, Sethabouppha, Thungjaroenkul and Likhitsathian2017; Moeini et al., Reference Moeini, Bashirian, Soltanian, Ghaleiha and Taheri2019; Osborn et al., Reference Osborn, Rodriguez, Wasil, Venturo-Conerly, Gan, Alemu, Roe, Arango, Otieno, Wasanga, Shingleton and Weisz2020; Salamanca-Sanabria et al., Reference Salamanca-Sanabria, Richards, Timulak, Connell, Mojica Perilla, Parra-Villa and Castro-Camacho2020; Newman et al., Reference Newman, Kanuri, Rackoff, Jacobson, Bell and Taylor2021; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Lin, Goldberg, Shen, Chen, Qiao, Brewer, Loucks and Operario2022) had small sample sizes that may have led to underpowered results. Moreover, only four studies (Ofoegbu et al., Reference Ofoegbu, Asogwa, Otu, Ibenegbu, Muhammed and Eze2020; Osborn et al., Reference Osborn, Rodriguez, Wasil, Venturo-Conerly, Gan, Alemu, Roe, Arango, Otieno, Wasanga, Shingleton and Weisz2020; Salamanca-Sanabria et al., Reference Salamanca-Sanabria, Richards, Timulak, Connell, Mojica Perilla, Parra-Villa and Castro-Camacho2020; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Lin, Goldberg, Shen, Chen, Qiao, Brewer, Loucks and Operario2022) reported precision estimates. There may also have been an element of placebo or Hawthorn effect in some studies. For example, those in the (waitlist) control group in the Newman et al. (Reference Newman, Kanuri, Rackoff, Jacobson, Bell and Taylor2021) study also experienced a statistically significant reduction in their anxiety scores.

Effectiveness of DMHIs for depression and anxiety

Three studies focussed specifically on depression. Ofoegbu et al. (Reference Ofoegbu, Asogwa, Otu, Ibenegbu, Muhammed and Eze2020) evaluated a 10-week long internet-based intervention with Nigerian university students using CBT principles. They found significant reductions in depression scores (p < .001), which were maintained at 4-week follow-up (p < .001). Moeini et al. (Reference Moeini, Bashirian, Soltanian, Ghaleiha and Taheri2019) administered a web-based intervention to school children underpinned by social cognitive theory/CBT principles in Iran over 6 months. Statistically significant improvement in depressive symptoms between baseline and 12 weeks were found (p < .05). This improvement did not continue past 24 weeks. Wannachaiyakul et al. (Reference Wannachaiyakul, Thapinta, Sethabouppha, Thungjaroenkul and Likhitsathian2017) utilised a 6-week long computerised intervention with inmates at a youth detention centre in Thailand. They found that depression scores reduced after entering the programme, and at 1- and 2-month follow-up (p < .05).

Four studies addressed both anxiety and depression. Newman et al. (Reference Newman, Kanuri, Rackoff, Jacobson, Bell and Taylor2021) evaluated a CBT-informed intervention for Indian university students with generalised anxiety disorder over 3 months. The intervention was associated with statistically significant reductions in anxiety (p ˂ .001) and depressive symptoms (p ˂ .001). Sun et al. (Reference Sun, Lin, Goldberg, Shen, Chen, Qiao, Brewer, Loucks and Operario2022) administered a mindfulness-based digital intervention using apps to Chinese university students with depression and anxiety symptoms over 4 weeks. This digital intervention led to statistically significant reductions in anxiety (p < .05), but not in depressive symptoms. Salamanca-Sanabria et al. (Reference Salamanca-Sanabria, Richards, Timulak, Connell, Mojica Perilla, Parra-Villa and Castro-Camacho2020) implemented a 3-month long CBT-based digital intervention among Colombian university students with depression. They found that treatment with iCBT led to significant reductions in depression (p < .001) and anxiety (p < .05) symptoms. Osborn et al. (Reference Osborn, Rodriguez, Wasil, Venturo-Conerly, Gan, Alemu, Roe, Arango, Otieno, Wasanga, Shingleton and Weisz2020) utilised a single session internet-based intervention on adolescents in a Kenyan high school. The intervention produced a statistically significant reduction in depressive symptoms from baseline to 2 week follow-up (p < .05), but not in anxiety symptoms. This was the only study to include those with moderate to severe depressive symptoms. Given the heterogeneity of included studies, comparing efficacy among interventions was not possible.

Quality assessment of included studies

The author assessed studies based on the CASP criteria (see Appendix 2) (CASP, 2020). All seven studies were judged to be of moderate quality. Aspects of the CASP criteria that studies performed well in were clearly addressing a focused research question (n = 6); detailing the method of randomisation (n = 7); accounting for loss to follow-up (n = 5); ensuring that both intervention and control groups were treated equally apart from the intervention (n = 7); ensuring comprehensive reporting of intervention effects (n = 7) and ensuring that the benefits of the trial outweighed the harms/costs (n = 7). However, areas of weakness included a lack of blinding of participants (n = 3); a lack of reporting around similarity between groups at the start of the trial (n = 4) and a lack of reporting on the precision of the treatment effect (n = 4).

Discussion

The present systematic review aimed to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of DMHIs on the mental health symptoms of YP in LMICs, assess the availability and quality of the current body of evidence on the topic, and provide practice and research recommendations for the use of DMHIs for YP in LMICs. With regard to the effectiveness of DMHIs, all studies included in this review reported statistically significant improvements in YP’s mental health outcomes. The use of the ‘gold standard’ RCT methodology in all identified studies supports confidence in their results. Notably, no studies were found reporting a worsening of symptoms, negative acceptability or dissatisfaction with DMHIs. However, this lack of negative findings may reflect publication bias favouring positive results. Future reviews could use a funnel chart to evaluate this. Regardless, we must apply caution when drawing conclusions from these studies, given the limitations of the studies reviewed.

No DMHIs identified in the review targeted other types of psychopathology aside from depression and anxiety. This is consistent with findings from a literature review focussing on DMHIs for adults in LMICs (Carter et al., Reference Carter, Araya, Anjur, Deng and Naslund2021). All but one study excluded those with severe symptoms, comorbidities, and those on psychotropic medication, psychological treatment or displaying self-harm/suicidal ideation. These factors limit the generalisability of the findings in three ways. Firstly, symptoms that were excluded from studies such as suicidal ideation are common in YP with depression/anxiety (Avenevoli et al., Reference Avenevoli, Swendsen, He, Burstein and Merikangas2015). By excluding these participants, study findings could only apply to a small subset of patients. Secondly, comorbid mental health conditions are common in YP (Angold and Costello, Reference Angold and Costello1993), further limiting the target population for these studies. Thirdly, the study findings are not applicable to a significant proportion of YP with more severe mental health issues (Tsehay et al., Reference Tsehay, Necho and Mekonnen2020). The studies in this review also largely targeted university students, making it difficult to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of DMHIs for children and adolescents. The heterogeneity in intervention types, outcome measures and study durations limited the possibility of conducting a meta-analysis, which could have strengthened conclusions about DMHIs’ effectiveness.

Considering the high recurrence rates and chronicity of common mental disorders, it is also vital to understand whether DMHIs have long-term effects (Koopmans et al., Reference Koopmans, Bültmann, Roelen, Hoedeman, Van Der Klink and Groothoff2011). This review found that DMHIs were not always able to sustain improvements in mental health symptoms. Moreover, the lack of meaningful long-term follow-up periods found in this review (mostly under 6 months), similar to the findings from a review of studies on DMHIs in HICs (Lehtimaki et al., Reference Lehtimaki, Martic, Wahl, Foster and Schwalbe2021), does not allow for a valid assessment of sustained treatment effects (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Kuosmanen and Barry2015). Despite the paucity of long-term data, a meta-analysis of HIC studies found three DMHIs showing significant improvements in depressive symptoms in YP after 6 months (Välimäki et al., Reference Välimäki, Anttila, Anttila and Lahti2017). However, the quality of data from HICs may be worse than that from LMICs. HIC studies were judged to have ‘consistently low quality’ in a large systematic overview (Lehtimaki et al., Reference Lehtimaki, Martic, Wahl, Foster and Schwalbe2021), while no studies were judged to be of low quality in this review. Furthermore, a systematic review (Grist et al., Reference Grist, Porter and Stallard2017) identified key limitations in HIC studies that were similar to those found in this review, such as small sample sizes, limited participant blinding and recruitment via self-selection.

Although all studies included in this review reported statistically significant improvements in YP’s mental health outcomes, the current review found varying effect sizes. This may be due to variations in recruitment strategy (Harith et al., Reference Harith, Backhaus, Mohbin, Ngo and Khoo2022), as web-based recruitment generally shows larger effect sizes than subject pool recruitment (Harrer et al., Reference Harrer, Adam, Baumeister, Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Auerbach, Kessler, Bruffaerts, Berking and Ebert2019). Sun et al. (Reference Sun, Lin, Goldberg, Shen, Chen, Qiao, Brewer, Loucks and Operario2022) (reporting a large effect size) recruited online, while Moeini et al. (Reference Moeini, Bashirian, Soltanian, Ghaleiha and Taheri2019) (reporting a small effect size) recruited via a subject pool. Those recruited online may already be more interested in DMHIs and could engage better with interventions than those recruited from a subject pool, leading to larger effect sizes.

Variation in effect size may also be influenced by participant adherence, as higher rates of adherence are generally associated with better treatment outcomes (Conley et al., Reference Conley, Durlak, Shapiro, Kirsch and Zahniser2016). Participants who adhere to an intervention may receive an increased ‘dose’ of an intervention leading to improved outcomes compared to those that drop out. The small effect size in the Moeini et al. (Reference Moeini, Bashirian, Soltanian, Ghaleiha and Taheri2019) study might therefore be related to the high dropout rate (30%) in the intervention group. Comparably to this review’s findings, literature from HICs reported low adherence and high dropout rates (Lehtimaki et al., Reference Lehtimaki, Martic, Wahl, Foster and Schwalbe2021). Completion rates in this review varied from 9% to 100%, similar to completion rates of 10%–94% found in a systematic review of DMHIs in HICs (Välimäki et al., Reference Välimäki, Anttila, Anttila and Lahti2017). Notably, the two studies that reported no loss to follow-up in our review either used a single session intervention (Osborn et al., Reference Osborn, Rodriguez, Wasil, Venturo-Conerly, Gan, Alemu, Roe, Arango, Otieno, Wasanga, Shingleton and Weisz2020) or an incarcerated population that may have had limited choice regarding participation (Wannachaiyakul et al., Reference Wannachaiyakul, Thapinta, Sethabouppha, Thungjaroenkul and Likhitsathian2017). Although HIC data also show that loss to follow-up could be lowered by using supported interventions, this review’s findings showed that supported interventions can still report high dropout rates (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Kuosmanen and Barry2015).

Although intervention design may impact the effectiveness of DMHIs (Chandrashekar, Reference Chandrashekar2018), it is difficult to evaluate the effectiveness of specific styles of intervention design in this review as none of the studies reported on specific design elements used. iCBT has been found to be as effective or more in treating YP’s anxiety and depression than traditional CBT in HICs (Ebert et al., Reference Ebert, Zarski, Christensen, Stikkelbroek, Cuijpers, Berking and Riper2015; Podina et al., Reference Podina, Mogoase, David, Szentagotai and Dobrean2016). This review’s outcomes support these findings. However, contrary to this review, Lehtimaki et al. (Reference Lehtimaki, Martic, Wahl, Foster and Schwalbe2021) found that apart from iCBT, there was inconclusive evidence for other types of DMHIs (e.g., mobile apps) in treating YP’s mental health issues in HICs. This could be because other digital interventions are highly tailored to the population group, country, and setting, which might have hindered appropriate comparisons between interventions.

HIC literature also supports the review’s findings on the lack of published data on DMHIs’ cost-effectiveness (Lehtimaki et al., Reference Lehtimaki, Martic, Wahl, Foster and Schwalbe2021). This could act as a barrier to implementing DMHIs in LMICs, as decision-makers may be reluctant to invest in an intervention when return on investment is unclear. Moreover, given financial constraints in LMICs, proving that an intervention is cost-effective could be key to its implementation.

Recommendations for future research and practice in LMICs

This review confirms the clinical effectiveness of DMHIs for YP in low-resource settings. They are potentially cost-effective treatment options that could permit large-scale dissemination and reduce healthcare worker burden (De Kock et al., Reference De Kock, Latham, Cowden, Cullen, Narzisi, Jerdan, Munoz, Leslie, Stamatis and Eze2022). With most of the world’s social media users located in LMICs (Shewale, Reference Shewale2023), there is significant potential to use DMHIs to reach large numbers of YP and support mental health promotion efforts and service delivery in these settings (Naslund et al., Reference Naslund, Bondre, Torous and Aschbrenner2020). However, despite the compelling evidence presented in this review, uptake and integration of DMHIs in health systems remains low, especially in LMICs (Torous et al., Reference Torous, Nicholas, Larsen, Firth and Christensen2018). Moreover, framing DMHIs as innovative approaches may lead to inappropriate enthusiasm to develop and implement technological solutions over other forms of intervention (WHO, 2020), further exacerbating health inequalities.

As per WHO digital health system strengthening guidelines (WHO, 2019), careful evaluation of benefits and harms is vital to avoid negative impacts on LMICs. Digital interventions that are incompatible with the needs and preferences of YP in LMICs may lead to inappropriate resource use, reduced clinical efficacy, and exacerbation of health inequalities (WHO, 2019). Given the digital divide between HICs and LMICs, the implementation of DMHIs without being coupled with campaigns (e.g., the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal [SDG] 9.c: “strive to provide universal and affordable access to the Internet in least developed countries by 2020”; [UN, 2015; UNDP, 2017]) to increase internet access may also exacerbate inequalities in access to mental health care and outcomes (UNICEF, 2017; ITU, 2023). Despite increases in global internet access and mobile phone use, connectivity in low-resource contexts still remains behind that of high-income contexts and international targets set under the Connect 2020 Agenda (ITU, 2014; UNDP, 2017; GSMA, 2022).

There are also inequalities in internet access within LMICs. For example, in low resource contexts, women, rural residents, older adults, persons with disabilities and those from lower socio-economic groups have the lowest rates of internet access (Naslund et al., Reference Naslund, Gonsalves, Gruebner, Pendse, Smith, Sharma and Raviola2019; GSMA, 2021, 2022). There are also regional and sub-regional inequalities in internet access within LMICs. For instance, sub-Saharan Africa has the lowest internet connectivity globally, and within this region, central Africa specifically has the lowest mobile broadband coverage on the continent (GSMA, 2022). Disparities in internet access between HICs and LMICs in addition to those within LMICs may therefore act as a barrier to the uptake of these technologies by vulnerable populations in low resource settings.

Given the digital divide in low resource contexts, opportunities for effective implementation of DMHIs in these settings may be maximised by equitably allocating resources (e.g., electricity, connectivity, and data) to address disparities in internet connectivity (ITU, 2021, Public Health Insight, 2023). Governments should deliver targeted policies to increase the uptake of DMHIs in underserved groups (e.g., increasing women’s internet connectivity through increasing access to digital resources, financial support and digital literacy skills; UNCTAD, 2023). Governments should also strategically align mental health care priorities with existing SDGs related to increasing internet access (ITU, 2021; Public Health Insight, 2023). For example, maximising access to technology (outlined in SDG 9) could also increase access to evidence-based mental health services (SDG 3) (UN, 2015; ITU, 2021; van Kessel et al., Reference van Kessel, Wong, Clemens and Brand2022; ITU and UNDP, 2023; Public Health Insight, 2023). By highlighting the co-benefits of digital health technologies, it may improve funding, roll out and implementation of innovative DMHIs in LMICs.

DMHIs may also increase the burden on healthcare staff. In this review, all identified interventions involved some level of external support. Although associated with improved treatment efficacy, implementation of an intervention with external support may be inappropriate in resource-constrained LMIC contexts (Grist et al., Reference Grist, Croker, Denne and Stallard2019). Investment in DMHIs may also be associated with an opportunity cost, potentially leading to reductions in funding to other elements of already strained LMIC health systems (WHO, 2019). Finally, given the lack of data on the cost-effectiveness of DMHIs, it is difficult to assess the financial burden of DMHIs on LMIC health systems (Lehtimaki et al., Reference Lehtimaki, Martic, Wahl, Foster and Schwalbe2021). A potential method of minimising costs and maximising benefits to LMIC healthcare systems could be to use trained non-specialist helpers to reduce resource use while providing digital support, which may increase the intervention’s efficacy and adherence (Hoeft et al., Reference Hoeft, Fortney, Patel and Unützer2018). A DMHI called ‘Step-by-Step’ created by the WHO for adult Syrian refugees in Lebanon has already used this approach, leading to improvements in depressive symptoms (Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Heim, Abi Ramia, Burchert, Carswell, Cornelisz, Knaevelsrud, Noun, van Klaveren, van’t Hof, Zoghbi, van Ommeren and El Chammay2022).

Although data show that some DMHIs are as effective as traditional mental health services (Karyotaki et al., Reference Karyotaki, Riper, Twisk, Hoogendoorn, Kleiboer, Mira, Mackinnon, Meyer, Botella, Littlewood, Andersson, Christensen, Klein, Schröder, Bretón-López, Scheider, Griffiths, Farrer, Huibers, Phillips, Gilbody, Moritz, Berger, Pop, Spek and Cuijpers2017; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Marais, Abdulmalik, Ahuja, Alem, Chisholm, Egbe, Gureje, Hanlon, Lund, Shidhaye, Jordans, Kigozi, Mugisha, Upadhaya and Thornicroft2017), poor adherence may limit their efficacy in the real world. This review highlighted the low levels of treatment adherence in five studies, agreeing with HIC data (e.g., in their review, Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Basu, Cuijpers, Craske, McEvoy, English and Newby2018 found that iCBT adherence ranged from 6% to 100%). Notably, adherence also tends to be higher in research studies than in real-world scenarios (Baumel et al., Reference Baumel, Edan and Kane2019). Additionally, DMHI acceptability tends to be lower than that for traditional mental health services (Kaltenthaler et al., Reference Kaltenthaler, Sutcliffe, Parry, Beverley, Rees and Ferriter2008). Strategies to improve YP’s engagement could involve co-designing interventions with YP, as highlighted by WHO guidelines (WHO, 2020). Co-design could also be key to ensure user buy-in, and to ensure that digital technologies are contextually and culturally relevant, and are integrated and adopted effectively into health systems (Economist Impact, 2022; NHS Race and Health Observatory, 2023). Effective co-design should utilise a multidisciplinary and multisectoral approach involving ministries of health, clinicians, carers and YP with lived experience of mental health conditions to capture the broad range of stakeholders involved in the digital mental health ecosystem (WHO, 2020; Sanz, Reference Sanz, Acha and García2021).

Given the challenges identified above, there is a need for increased research on this topic. Specifically, more rigorous RCTs with larger sample sizes are needed to increase confidence in the clinical significance and power of results, and permit synthesis of high-quality evidence through meta-analysis. Future studies should have a broader geographic coverage (especially focussing on unrepresented areas such as from Oceania, the Caribbean or Central Asia). The scope of studies should also be increased. Studies should focus on a broader range of mental health interventions apart from iCBT. Future research should also include participants with a wider range of psychopathologies, symptom severity, comorbidities and on psychotropic medication to increase the generalisability of study findings and ability to implement findings in real-world healthcare settings.

The quality of studies could be improved by ensuring that studies report standardised effect sizes and statistical significance to allow for findings to be compared across studies and meaningful conclusions to be made. Studies should aim to reduce self-selection during recruitment, attempt to reduce loss to follow-up, and ensure that participants and researchers are blinded. Studies should also focus on neglected yet important aspects of DMHIs, such as reporting on intervention design to evaluate the impact of design elements on treatment efficacy, and cost-effectiveness to improve potential for implementation. Studies should also report follow-up periods and aim to produce long-term follow-up data by ensuring follow-up for over 6 months. Such efforts could generate new and important findings about methods of action for effective interventions, enhance intervention acceptability, improve intervention generalisability and ensure that new technologies are more sustainable and can be better integrated into existing mental health systems.

It is also key for future studies to examine the implementation processes of intervention studies to help support understanding on their effectiveness and mechanisms of impact. As per UK Medical Research Council guidelines (Craig et al., Reference Craig, Dieppe, Macintyre, Mitchie, Nazareth and Petticrew2008; Skivington et al., Reference Skivington, Matthews, Simpson, Craig, Baird, Blazeby, Boyd, Craig, French, McIntosh, Petticrew, Rycroft-Malone, White and Moore2021), ensuring that implementation is considered early in the intervention process and throughout intervention development, feasibility testing, process and outcome evaluation are key. This increases the potential of developing interventions that can be adopted and sustained in a real-world context.

Limitations

This review has a number of limitations. It is notable that four out of the seven included papers were found via handsearching and not identified in the database search. This implies a lack of sensitivity in the search strategy. The author was not able to identify the reason for this, despite ensuring the key terms from hand-searched papers were included in the main search strategy and checking the search strategy with LSHTM library staff. Moreover, due to the large variation in outcome measures, intervention types and study durations, it was not possible to conduct a quantitative synthesis of findings and meta-analysis, which limits the validity of the review’s conclusions. Finally, excluding non-English language studies in the search may have led to the authors missing key articles in other languages.

Conclusions

The present systematic review is the first to identify and synthesise the current body of literature evaluating the clinical effectiveness of DMHIs for YP in LMICs. The findings suggest the effectiveness of digital technologies, especially iCBT-based interventions, to address depression and anxiety in this population. Importantly, the findings are also consistent with growing evidence on DMHIs from HICs that show potential for DMHIs to improve mental health conditions in YP. However, the evidence in this review is limited to only seven studies and should be treated with caution.

This review, combined with emerging recent evidence, highlights opportunities for DMHIs to address the burden of mental illness and global inequalities in effective mental health care for YP. It also identifies the need to improve the quantity and quality of available evidence on the topic through increased rigorous research. Finally, this review also highlights opportunities to utilise evidence-based policy mechanisms to increase the impact of DMHIs in LMICs.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2024.71.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2024.71.

Data availability statement

The author confirms that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Prof Bayard Roberts for his support with publishing this manuscript. The author would like to thank friends, family and partners for their support with this project.

Author contribution

J.A. wrote the original manuscript, created the search strategy, conducted the first search and led data extraction. D.C. conducted the second search, co-wrote and prepared the manuscript for publication. S.B. created the graphical abstract and aided in the second search.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest

The authors declare none.

Comments

Young people have an increased vulnerability to mental health conditions, and those living in low- and middle-income countries face disproportionate barriers in accessing high quality mental health care. Given increasing digital connectivity in the global south, digital mental health interventions (DMHIs) show promise in improving mental health outcomes for these populations by circumventing key barriers to care. In this systematic review, we evaluate the quality and availability of evidence on the effectiveness of DMHIs for young people and use this to provide evidence-based policy recommendations to improve youth mental health outcomes. Our findings show evidence of the effectiveness of multiple forms of DMHI (especially internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy) on anxiety and depression outcomes. At the same time, our results show a lack of high-quality studies on the topic, characterised by high dropout rates, small sample sizes and insufficient data on the statistical significance of treatment effects and long-term benefits of treatment. Our findings highlight that DMHIs have the potential to improve youth mental health outcomes in these settings but given the lack of robust data, increased adoption of these technologies would require further research on the topic.