Introduction

The dissolution of marriage is common, affecting 46% of married couples in the USA, 42% in Australia, and 43% in Europe [1–3]. In many cases, separated couples have children together (i.e., 47% of couples in Australia, 57% in Spain, 48% in the UK, with an average of 1.8 and 2 children per separated couple in Australia or the UK, respectively) [2,4,5].

Parental separation has consequences in children’s life, including exposure to conflict between parents, economic loss, reduced contact with one parent, and increased life stressors such as changing schools, childcare, or homes. Parental separation has become one of the most common adverse childhood experiences, second only to socioeconomic disadvantage [Reference Sacks and Murphey6,7]. Two systematic reviews have reported that children of separated parents have an increased risk of mood and drug use disorders [Reference Sands, Thompson and Gaysina8,Reference Schlossarek, Kempkensteffen, Reimer and Verthein9]. Evidence reported in two other systematic reviews also shows an increased risk of psychosis in people who have experienced other adversities during childhood such as physical or sexual abuse [Reference Varese, Smeets, Drukker, Lieverse, Lataster and Viechtbauer10,Reference Matheson, Shepherd, Pinchbeck, Laurens and Carr11]. However, the studies on the associations between parental separation and psychosis have not been critically appraised or summarized. Therefore, the relevance of parents’ separation on the development of psychotic disorders remains uncertain for clinicians, patients and parents, social workers, psychologists, counselors, and educators.

Strong evidence on the association between parental separation and psychosis could identify people at higher risk of having psychotic disorders and inform a proactive and multidisciplinary approach to them. This systematic review and meta-analysis present an up-to-date critical appraisal and summary of the available evidence on the risk of developing psychotic disorders in children of separated parents.

Methods

The Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology criteria were used to undertake this review [Reference Stroup, Berlin, Morton, Olkin, Williamson and Rennie12]. Observational studies, including published papers and conference abstracts, reporting risk of psychotic disorders in children of separated couples were searched in PUBMED, EMBASE, PsychINFO, and Web of Science from database inception until the 7th of September 2019. The following search strategy was used: (((((((((((“Divorce”[Mesh]) OR ((((((parent*) OR Family) OR Marital) OR “Marriage”[Mesh])) AND separation)) OR ((((“Marriage”[Mesh]) OR Marital)) AND dissolution))))))))) AND (((((((psychoses) OR psychosis) OR “Hallucinations”[Mesh]) OR “Delusions”[Mesh]) OR “Schizophrenia”[Mesh]) OR (“Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders”[Mesh])) OR “Psychotic Disorders”[Mesh])).

The bibliography lists of all papers fitting the inclusion criteria, and relevant reviews identified in the initial search, were checked for further articles. Papers citing all the included studies or relevant reviews were also searched in the Web of Science and considered for inclusion. There were no restrictions on the basis of language, sample size, or duration of follow-up.

The following articles were not included: interventional studies; papers that presented only associations with specific domains or outcomes of psychosis; studies with composite outcome (i.e., mental health disorders) unless separate results for psychosis were presented; those reporting outcome as a continuous variable (i.e., score in psychosis scales); articles presenting only subclinical psychosis or drug induced psychotic disorders; studies comparing participants with different mental health disorders instead of those with and without psychosis; papers in which the exposure was separation between parent and child but parental separation was not one of the reasons for this; those conducted in specific patient subpopulations (i.e., exposure assessed only on participants receiving specific medication); studies reporting results only from univariate analysis; and ecological studies.

One researcher (L.A.) conducted all searches of eligible studies. Eligibility was confirmed by two other researchers (M.P.-P. and S.A.). In some cases, the authors of the studies were contacted for any clarifications required including possible publication of two papers from the same sample. Where data from the same participants were presented in more than one paper, only data from the study with larger sample size were included in the analysis. Two researchers extracted the data from all the eligible studies (L.A. and S.A.) using a standardized data-collection form. The risk of bias and overall methodological quality of the studies fitting the inclusion criteria was assessed using the Quality Assessment Tools for Case–Control, Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies of the National Institute of Health (USA) [13].

Statistical methods

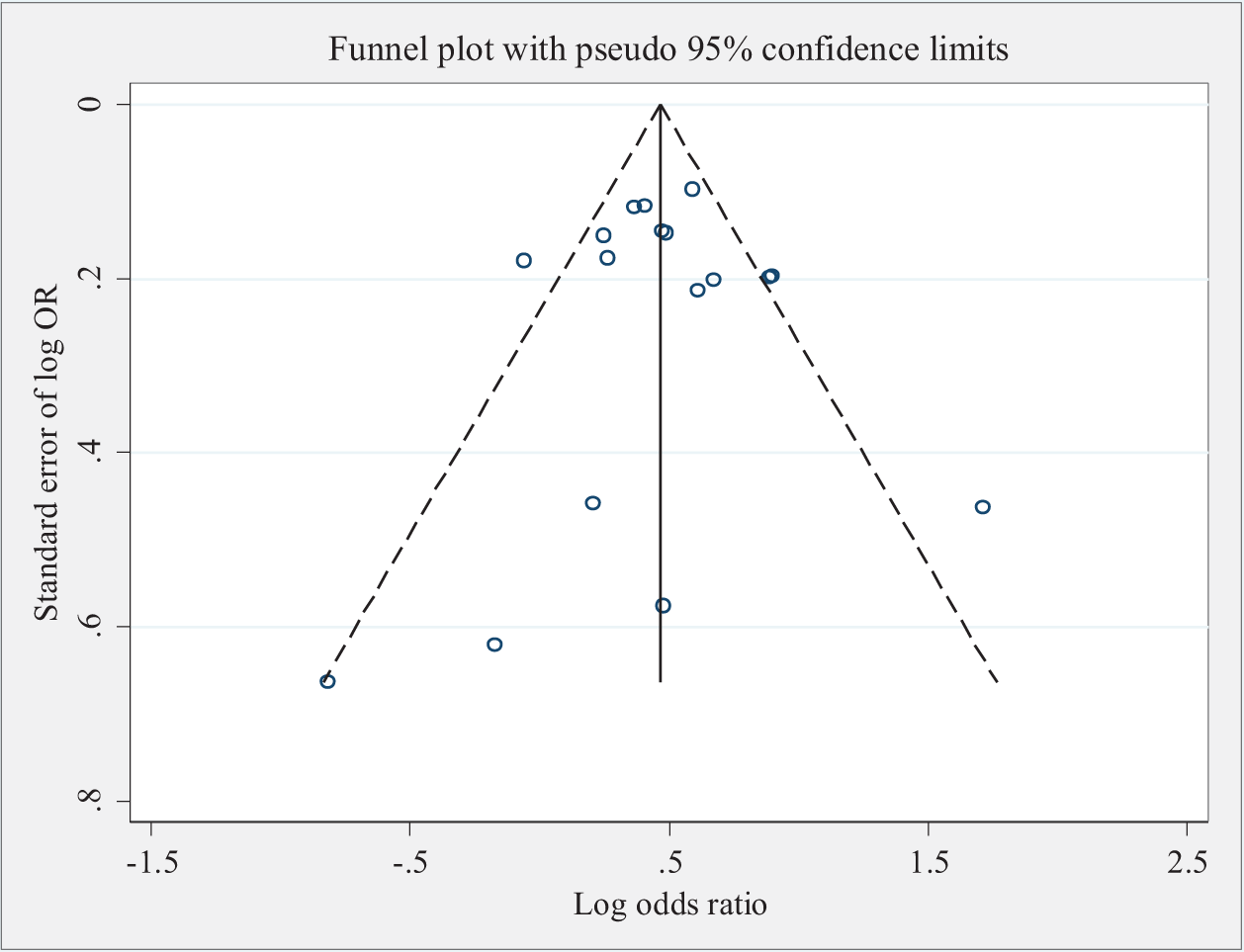

Pooled estimates of odds ratios (ORs) were obtained using random-effects models [Reference DerSimonian and Kacker14]. ORs and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to present results. p value ≤0.05 was used as a criterion for significance. The heterogeneity between studies was measured using I-squared index (I 2), which represents inconsistency of the studies included and estimates the percentage of the total variation due to heterogeneity rather than chance [Reference Higgins and Thompson15] All studies included had reported ORs as an estimate of the association between parental separation and psychosis, except two where the relative risk (RR) [Reference Hansagi, Lena and Sven16] and the hazard ratio (HR) [Reference Bjorkenstam, Burstrom, Vinnerljung and Kosidou17] were used. The two estimates were treated as proxies for ORs. For the RR, the prevalence of psychosis was low (<10%), making the two estimates fairly similar; for the HR, the estimate is widely used as a proxy for OR [Reference Zhang and Yu18,Reference Stare and Maucort-Boulch19]. To assess heterogeneity and its impact on the pooled estimates, sensitivity analyses were used: (1) stratifying studies by study design (case–control, cohort, and cross-sectional), (2) excluding studies where the exposure was the separation between parent and child for different reasons, including, but not exclusively, parental separation, (3) excluding cross sectional studies, and (4) excluding studies that had a very wide CI or reported results very different to the rest. A funnel plot was used to investigate possible publication bias. The software Stata v14.0 was used for the analysis [20].

Results

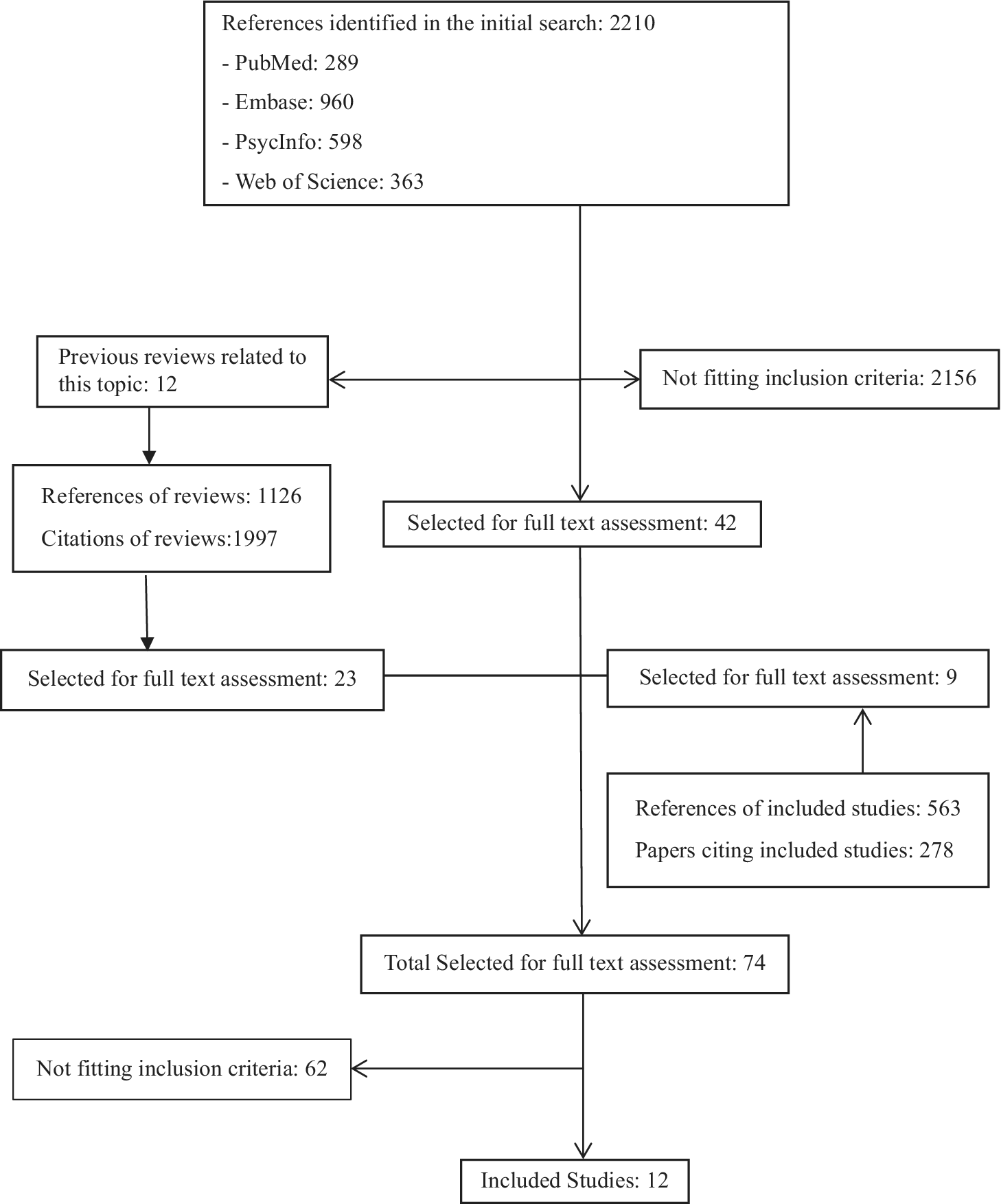

The electronic search produced 2,210 references, 289 from PUBMED, 960 from EMBASE, 598 from PsychInfo, and 363 from Web of Science. Twelve reviews relevant to the topic, with a total of 1,126 references, and cited by 1,997 papers were also identified [Reference Varese, Smeets, Drukker, Lieverse, Lataster and Viechtbauer10,Reference Matheson, Shepherd, Pinchbeck, Laurens and Carr11,Reference Olin and Mednick21–Reference Peh, Rapisarda and Lee30]. The results of the search are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Results of literature search.

Twelve papers including in total 305,652 participants were considered eligible [Reference Hansagi, Lena and Sven16,Reference Bjorkenstam, Burstrom, Vinnerljung and Kosidou17,Reference Furukawa, Mizukawa, Hirai, Fujihara, Kitamura and Takahashi31–Reference Shevlin, McElroy, Christoffersen, Elklit and Hyland40]. These studies had been conducted in 22 different countries, 9 of them were based in Europe, 2 in Asia, and 1 collected data from participants based in America, Africa, Asia, and Europe. Six were case–control studies [Reference Furukawa, Mizukawa, Hirai, Fujihara, Kitamura and Takahashi31–Reference Trotta, Di Forti, Iyegbe, Green, Dazzan and Mondelli35,Reference Stilo, Gayer-Anderson, Beards, Hubbard, Onyejiaka and Keraite37]. Five were cohort studies with follow up between 3 and 26 years [Reference Hansagi, Lena and Sven16,Reference Bjorkenstam, Burstrom, Vinnerljung and Kosidou17,Reference Merikukka, Ristikari, Tuulio-Henriksson, Gissler and Laaksonen38–Reference Shevlin, McElroy, Christoffersen, Elklit and Hyland40]. One of them only included male participants [Reference Hansagi, Lena and Sven16]. The remainder study had a cross-sectional design and data have been collected on psychosis and parental separation at an earlier time [Reference McGrath, McLaughlin, Saha, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi and Alonso36]. The sample size ranged from 347 to 107,704 participants. In seven studies, the exposure was exclusively parental separation [Reference Hansagi, Lena and Sven16,Reference Bjorkenstam, Burstrom, Vinnerljung and Kosidou17,Reference Rubino, Nanni, Pozzi and Siracusano33,Reference Trotta, Di Forti, Iyegbe, Green, Dazzan and Mondelli35,Reference McGrath, McLaughlin, Saha, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi and Alonso36,Reference Merikukka, Ristikari, Tuulio-Henriksson, Gissler and Laaksonen38,Reference Zhang, Zhu, Sun, Guo, Wu and Wang39]. The other five papers used a broader exposure representing the child becoming separated from one or both parents due to parental separation or other causes such as death of parent or abandonment of child [Reference Furukawa, Mizukawa, Hirai, Fujihara, Kitamura and Takahashi31,Reference Morgan, Kirkbride, Leff, Craig, Hutchinson and McKenzie32,Reference Stilo, Di Forti, Mondelli, Falcone, Russo and O'Connor34,Reference Stilo, Gayer-Anderson, Beards, Hubbard, Onyejiaka and Keraite37,Reference Shevlin, McElroy, Christoffersen, Elklit and Hyland40]. Four studies used a clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia as outcome [Reference Hansagi, Lena and Sven16,Reference Furukawa, Mizukawa, Hirai, Fujihara, Kitamura and Takahashi31,Reference Rubino, Nanni, Pozzi and Siracusano33,Reference Merikukka, Ristikari, Tuulio-Henriksson, Gissler and Laaksonen38]. Seven studies used a clinical diagnosis of psychotic disorders [Reference Bjorkenstam, Burstrom, Vinnerljung and Kosidou17,Reference Morgan, Kirkbride, Leff, Craig, Hutchinson and McKenzie32,Reference Stilo, Di Forti, Mondelli, Falcone, Russo and O'Connor34,Reference Trotta, Di Forti, Iyegbe, Green, Dazzan and Mondelli35,Reference Stilo, Gayer-Anderson, Beards, Hubbard, Onyejiaka and Keraite37,Reference Zhang, Zhu, Sun, Guo, Wu and Wang39,Reference Shevlin, McElroy, Christoffersen, Elklit and Hyland40]. Finally, one study used psychotic disorder as outcome defined with a score above a cut-off point in a scale [Reference McGrath, McLaughlin, Saha, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi and Alonso36]. The characteristics of all included papers are presented in Table 1. They were all considered to be of high quality (Appendix A).

Table 1. Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis.

Abbreviations: CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; CC, case–control study; CS, cross-sectional study; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; MINI, Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview.

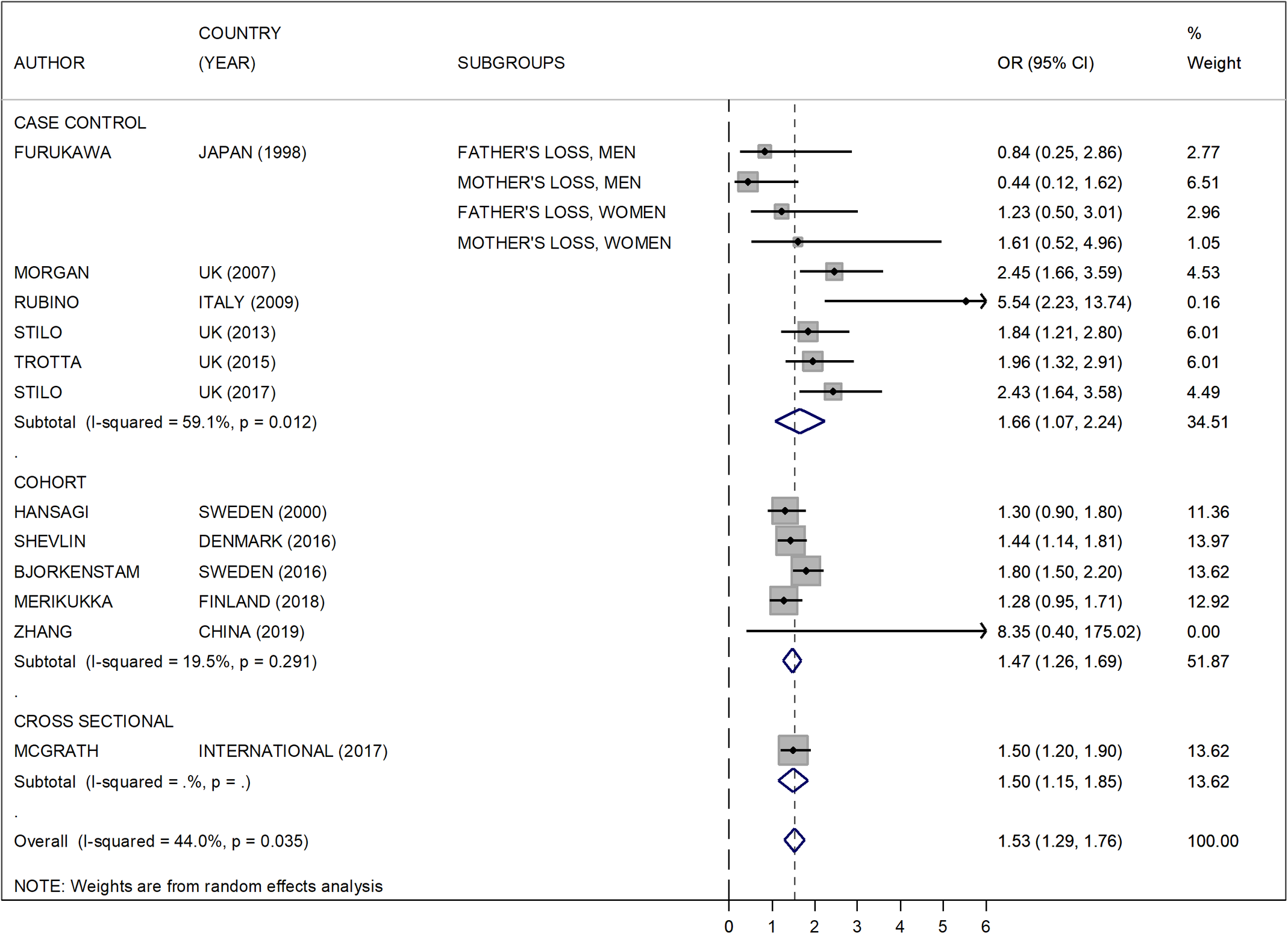

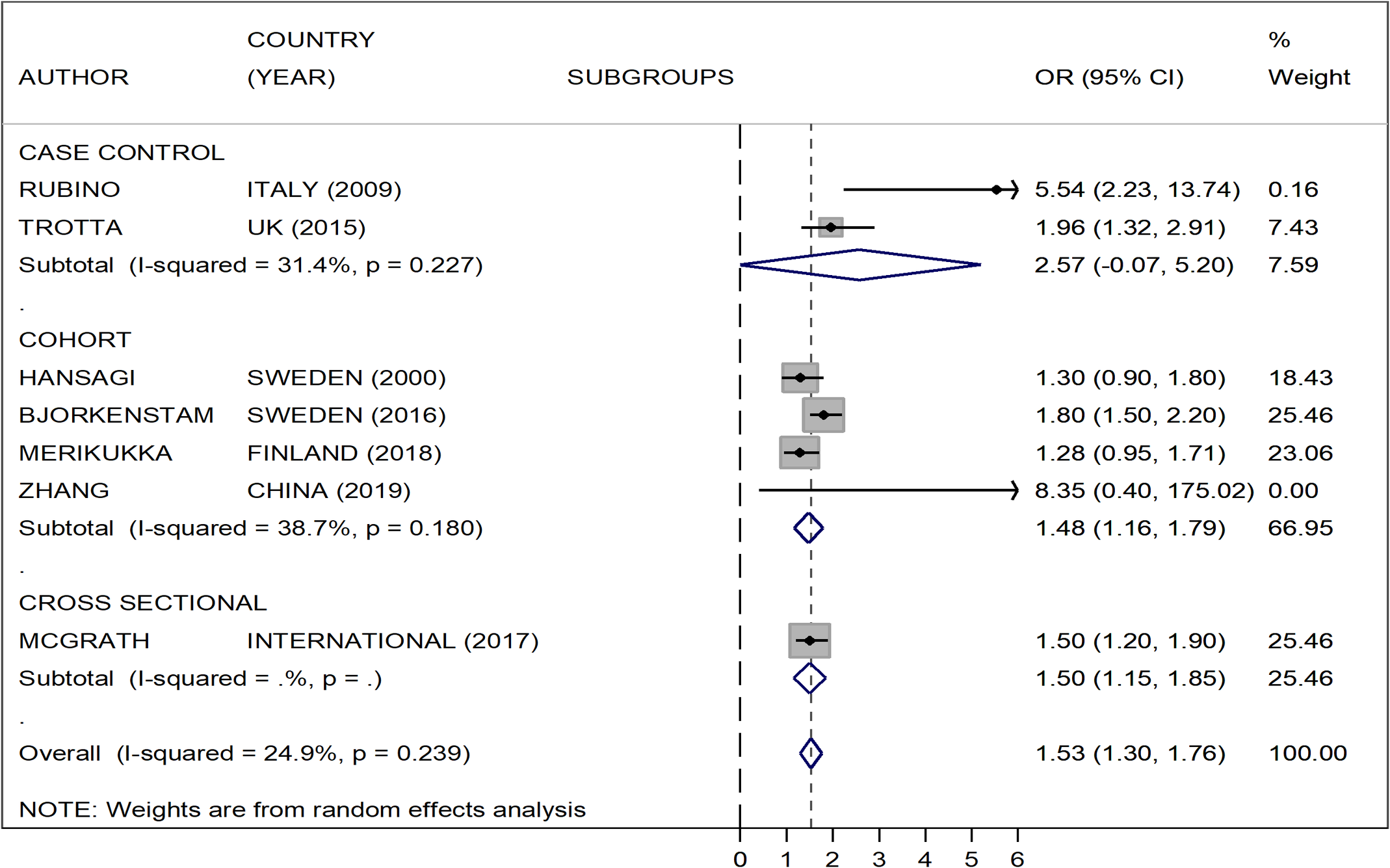

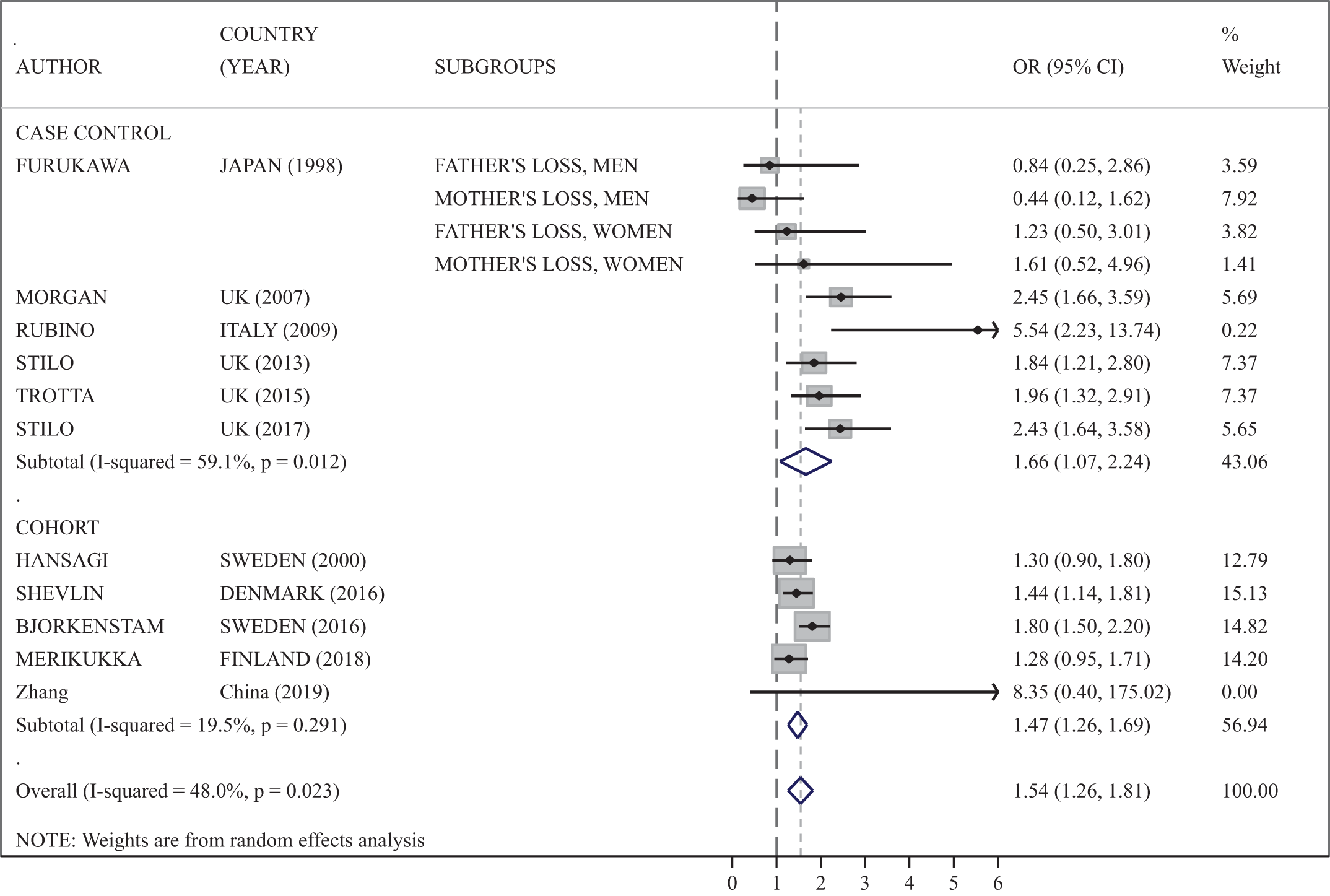

The meta-analysis showed that parental separation is significantly associated with psychosis, OR: 1.53 (1.29–1.76; Figure 2). The heterogeneity of the studies was 44.0% and varied depending on the study design. The association was also significant when studies were categorized by design, cohort, case–control, or cross-sectional studies for each individual category. The five cohort studies showed and increased risk of psychosis, OR: 1.47 (1.26–1.69), consistent with the overall pooled estimate and a lower level of heterogeneity (19.5%). When the studies where the exposure was the separation between parent and child for different reasons, including, but not exclusively, parental separation, were excluded from the meta-analysis, the overall risk of psychosis was OR: 1.53 (1.30–1.76) with heterogeneity 24.9% (Figure 3). When the cross-sectional study was excluded, the overall risk of psychosis changes minimally, OR: 1.54 (1.26–1.81), with heterogeneity of 48.0% (Appendix B).

Figure 2. Risk of psychosis in children of separated parents (all studies included).

Figure 3. Risk of psychosis in children of separated parents excluding studies where the exposure was the separation between parent and child for different reasons, including, but not exclusively, parental separation.

One cohort study had a very wide CI. The study weight approached zero with minimal impact on the overall estimate [Reference Zhang, Zhu, Sun, Guo, Wu and Wang39]. One case–control study reported a risk between two and five times higher than the one reported in all the other studies [Reference Rubino, Nanni, Pozzi and Siracusano33]. However, when these two studies were removed from the meta-analysis the pooled OR did not show major changes: 1.52 (1.29, 1.76) and heterogeneity 48.0%. All pooled estimates showed significantly increased risk with p < 0.001. The funnel plot demonstrated a reasonable symmetry suggesting that publication bias and other sources of biases due to methodology, quality, and small studies effect are unlikely (Appendix C).

Discussion

Children of separated parents have a risk of psychosis increased by 53%. This association remains significant when studies are categorized by methodology or design. Two previous systematic reviews have reported the association between parental separation and other mental health problems with an increased risk of depression and cannabis dependence for children of separated parents [Reference Sands, Thompson and Gaysina8,Reference Schlossarek, Kempkensteffen, Reimer and Verthein9]. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first review reporting on the association between parental separation and psychotic disorders.

The increased risk of psychosis for children of separated parents is consistent with the increased risk for those exposed to other childhood adversities, such as sexual, emotional, physical abuse, or neglect, reported in another systematic review [Reference Varese, Smeets, Drukker, Lieverse, Lataster and Viechtbauer10].

The mechanisms that explain the association between parental separation and psychotic disorders are likely to be complex and include neurological, psychological, and social factors. A prolonged situation of stress in a child, experienced before or after the separation, can lead to some pathophysiological changes including dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and increased oxidative stress in the central nervous system, which are both associated with the development of psychosis [Reference Morgan and Gayer-Anderson26,Reference Schiavone, Colaianna and Curtis41]. Childhood adversities can also have a psychological impact on mood, stress regulation, self-concept, social roles, cognitive styles, coping responses, attachment representations, and dissociative mechanisms [Reference Matheson, Shepherd, Pinchbeck, Laurens and Carr11,Reference Morgan and Gayer-Anderson26,Reference Bentall, de Sousa, Varese, Wickham, Sitko and Haarmans28]. Family arrangements after separation can also have an explanatory role in the association between parental separation and psychotic disorders. A large cohort study reported that children growing up with single parents had an increased risk of serious psychiatric disorders, suicide, or alcohol addiction [Reference Weitoft, Hjern, Haglund and Rosen42]. The increased rate of substance use in children of separated parents could also be an explanatory factor for the association between parental separation and psychotic disorders [Reference Schlossarek, Kempkensteffen, Reimer and Verthein9,Reference Waldron, Grant, Bucholz, Lynskey, Slutske and Glowinski43,Reference Windle and Windle44]. However, the evidence on the neurological, psychological, and social mechanisms that link parental separation and psychotic disorders requires further research. For example, the effect of many familial factors is unclear; the role of family dysfunctionality, domestic violence, drug, or alcohol abuse in parents, together with physical or mental illness in the family, the presence of siblings, and financial issues require more research. Future studies could also address the vulnerability of patients of certain age and gender, those who experience other adversities in childhood or adult life, together with genetic factors and medical conditions that may increase the risk of mental illness. The protective factors that make resilient some people exposed to childhood adversities including parental separation also need more studies [Reference Morgan and Gayer-Anderson26].

This review has some limitations. The diversity of the methods across studies may have an effect on the external validity of each individual one. In general, case–control studies have several limitations including that the temporality between cause and effect is more difficult to establish, there can be selection bias of the controls, and the information collected from the control is prone to recall bias. Case–controlled studies showed a significant association between parental separation and psychosis, but larger heterogeneity than cohort studies. Furthermore, only one doctor conducted the initial search (L.A.). Even so, all data were checked for accuracy on multiple occasions and all analyses were conducted several times and checked by a senior statistician (S.A.). Finally, some publications may have been miscoded or missed altogether.

This study has strengths as well. The comprehensive search and critical assessment of studies conducted in this review allows estimation of the association between parental separation and psychosis obtained on a large number of participants assessed worldwide. The use of a random effect model, based on the assumption that studies were independently conducted and do not necessarily share a common effect size, allowing for more uncertainty of the final summary estimate, was a conservative choice. The overall estimate remained significant despite the increased width of the confidence intervals, providing support to the significance of the findings. The reasonably symmetrical funnel plot suggests provides no evidence of publication bias or small study effects [Reference Sterne, White, Carlin, Spratt, Royston and Kenward45].

The risk of psychosis is higher for children exposed to other adversities such as sexual, emotional, physical abuse, or neglect (OR > 2) than for children of separated parents. However, the higher frequency of parental separation can result in a larger number of cases of psychosis associated with it in the population [1–3]. Parents, educators, and clinicians have to be alert to the symptoms that could indicate the need for intervention [Reference Cohen and Weitzman46]. Usually, the intervention of mental health professionals is not necessary after a separation, although this adversity as well as others should be routinely recorded, when seeing patients with potential psychosis. The approach to children of separated parents may need to be multidisciplinary as the associations between parental separation and other adverse outcomes such as poorer physical health, academic performance, and social interaction have also been reported [Reference Amato22,Reference Cuijpers, Smit, Unger, Stikkelbroek, Ten Have and de Graaf47].

Conclusion

Parental separation is associated with an increased risk of psychosis. This should be acknowledged by all professionals working with children of separated parents. Although the risk for an individual child of separated parents is still very low, given the high proportion of couple that separate, the increased rates of psychosis may be substantial in the population. Future studies addressing the possible mechanisms for this association are required.

Financial Support

S.A. was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Assessment of case‑control studies.

Assessment of cohort and cross sectional studies.

Appendix B. Risk of psychosis in children of separated parents in cohort and case-control studies (cross sectional study not included).

Appendix C. Funnel plot. Publication bias assessment.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.