1. Introduction

Korean popular music (K-pop) has expanded its cultural reach among Western audiences over the past 20 years (Lie, Reference Lie2015), and groups like BTS and BLACKPINK have achieved unprecedented global success recently (McIntyre, Reference McIntyre2022). As K-pop evolves into a global cultural export, scholars have paid more attention to the code-mixing of English within its lyrics (Yeo, Reference Yeo2018; Ahn, Reference Ahn, Low and Pakir2021).

While early scholarship on English code-mixing in K-pop lyrics identified English as a medium of expressing taboo topics and indexing cosmopolitanism (Lee, Reference Lee2004), recent analyses reinterpret English use as an index of fun and globality (Ahn, Reference Ahn, Low and Pakir2021). Yeo (Reference Yeo2018: 112–113) proposes that K-pop producers employ moderation, managing the proportion of English and Korean language within song lyrics to balance evolving market conditions, and reformulation, the creation of a ‘nonnative’ brand of English use to simultaneously index a global and distinctly Korean identity. In other words, Yeo (Reference Yeo2018) proposes that English use in K-pop reflects the genre's expanding reach beyond Korean and Pan-Asian contexts.

Linguistic studies on English use in K-pop have identified syntactic patterns of borrowing (Lawrence, Reference Lawrence2010; Yang, Reference Yang2012), appropriation of African American Language (AAL) (Lee, Reference Lee2007; Garza, Reference Garza2021), code ambiguation (Ahn, Reference Ahn, Low and Pakir2021; Lee, Reference Kang2022), and English use in artist names and song titles (Yeo, Reference Yeo2018; Kang, Reference Kang2022). However, few (if any) studies have quantitatively examined Yeo's proposed phenomenon of moderation within the lyrics themselves. In other words, what is the balance of English and Korean language use in the lyrics of globally successful K-pop groups? Has that balance shifted as K-pop's fanbase has expanded?

Quantitatively, this article focuses on 58 singles released by four idol groups from 2015 to 2022: BTS, BLACKPINK, TWICE, and Itzy. These four groups have demonstrated substantial European and Pan-American listenership by surpassing six million monthly listeners on the streaming application Spotify in 2021. By analyzing the number of English and Korean types (unique words) in each song, this analysis will show that the threshold of moderation, or the proportion of English types to total types in these songs have steadily increased from 2015 to 2022. In other words, as K-pop shows more sustainable growth in Western markets, producers seem to expand artists’ use of English to widen the linguistic foothold, or ‘points of entry’ for listeners more familiar with English (Takacs, Reference Takacs2014: 130). Next, this paper examines code ambiguation, or an utterance that carries meaning in both English and Korean, within the title and hook of Itzy's 2019 debut single ‘DALLA DALLA.’ However, this code ambiguation seems to undergo reformulation into a new lexeme within an emerging register of K-pop English (Yeo, Reference Yeo2018) within a re-released English version of the song. It is possible that such reformulation serves to balance Itzy's appeal between local Korean-speaking and global, English-speaking audiences.

Therefore, this mixed methods article aims to address the following research questions:

(1) How has rapid internationalization influenced the balance of English and Korean language use within the lyrics of four breakthrough K-pop groups?

(2) How does Itzy's use of English in the original and English re-release of their debut track reflect the internationalization of K-pop?

2. Background: The internationalization of K-pop

Music has become a popular site of discussion within the literature of globalization and transcultural flows (Pennycook, Reference Pennycook2006), particularly how cultures around the world consume, appropriate, and recontextualize hip-hop music to reflect local sociohistorical contexts (Alim, Ibrahim & Pennycook, Reference Alim, Ibrahim and Pennycook2008; Terkourafi, Reference Terkourafi2010). As another musical genre negotiating globalizing cultural flows, K-pop is one facet of hallyu, or Korean wave(s) – a proliferation of South Korean (Korean) exports of media, fashion, culture, and soft political power. Yoon and Jin (Reference Yoon and Jin2017) mark 1997 as the inception of the first Korean Wave, defined by a neoliberal turn in Korean economic policy and an unexpected boom in Korean television drama viewership across East Asia. While scholars have documented the modest successes of K-pop artists like BoA (Jung, Reference Jung, Fitzsimmons and Lent2016a) and Wonder Girls (Fuhr, Reference Fuhr2015) in U.S. markets, Psy's worldwide hit ‘Gangnam Style’ (2012) marks K-pop's most pronounced globalized breakthrough, breaking viewership records on YouTube (Jung, Reference Jung, Fitzsimmons and Lent2016a). Groups like BTS and BLACKPINK later solidified footholds among European and pan-American audiences in part through collaborations with well-known Western artists like Steve Aoki, Halsey and Selena Gomez (Yeo, Reference Yeo2018).

Fans often organize K-pop groups into four ‘generations’ demarcated by inflection points in the growth of the genre. The first generation corresponds with the first Korean Wave (1997–2005), defined by major growth in listenership across East Asia. The second generation precedes the rise in global social media use (2006–2012). The third generation corresponds with K-pop's social-media-fueled ascension toward global prominence (2012–2018). And the fourth generation exemplifies a post-global, ‘borderless’ evolution of contemporary K-pop (2018–present day) (Kang, Reference Kang2020).

Scholars attribute many factors to the growth of K-pop exports in the 21st century including strong appeals to the visual and kinesthetic (e.g., fashion and music videos) (Fuhr, Reference Fuhr2015; Lie, Reference Lie2015), early adoption of fan-driven marketing via YouTube (Ahn, Reference Ahn2017), and use of social media to lower geographic barriers for artist-fan interaction (Jung, Reference Jung, Shin and Lee2016b). Such fan-to-fan and fan-to-artist interactions facilitate prosumerism (a portmanteau of producer and consumer) (Toffler, Reference Toffler1980) where fans consume, share, and remix content (e.g., reaction, commentary, and dance videos), and thereby iteratively inform entertainment companies’ future productions (Crow, Reference Crow2019). As a result, some argue that K-pop groups’ use of English has expanded to ‘build a linguistic gateway to connect with international fans’ (Ahn, Reference Ahn, Low and Pakir2021: 223).

The groups in this analysis, BTS, BLACKPINK, TWICE, and Itzy, are among the few Korean groups to reach six-million monthly listeners on the music streaming service Spotify (Scott, Reference Scott2021). The rise of streaming apps like Spotify, YouTube Music, and Apple Music further facilitates K-pop's international reach by lowering previous barriers to entry like purchasing CDs, making K-pop more capable of breaching national and cultural borders (Yoon & Jin, Reference Yoon and Jin2017). Furthermore, a large listenership on Spotify is one reliable benchmark for a K-pop group commanding a substantial Western audience as 80% of Spotify users reside in Europe or the Americas (Iqbal, Reference Iqbal2022).

K-pop's global breakthrough and ongoing negotiation of meaning among a diverse fanbase represents the hybridization of a genre within what Appadurai (Reference Appadurai, Williams and Chrisman1994) coins as mediascapes or a fluid, shifting medium through which diverse cultures appropriate and negotiate the meanings of images and entertainment texts circulated in a globalizing world. In post-war South Korea, transcultural flows could be described as unidirectional consumptionFootnote 1 and subsequent adoption of mostly Black U.S. musical genres (Anderson, Reference Anderson2020). And while that pattern continues to this day (Garza, Reference Garza2021), scholars question the unidirectionality of these transcultural flows as Korean cultural exports proliferate (Jin, Reference Jin2016). However, Jin also argues that power differentials between Korea-U.S. media flows and global-local markets mean that flows between Korean and Western media markets are not reversed but moving bidirectionally.

This study considers singles released by three third-generation K-pop groups (BTS, BLACKPINK, and TWICE) and one fourth-generation group (Itzy). BTS, a boy group who debuted in 2013, is the most decorated of the four, first charting in the Billboard Hot 100Footnote 2 in 2017 with their song ‘D.N.A.’ They currently share the record for most number-one singles on the Billboard Global 200Footnote 3 with six. This includes three English-language releases: ‘Dynamite,’ ‘Butter’, and ‘Permission to Dance.’ BLACKPINK, a girl group who debuted in 2016, first hit the Billboard Hot 100 with their single ‘Ddu-du Ddu-du’ in 2018. In 2022, their singles ‘Shut Down’ and ‘Pink Venom’ both reached number one on the Billboard Global 200 in consecutive months. TWICE debuted under the JYP Entertainment label in 2015 with substantial popularity in Korea and Japan before finding greater traction on the global stage. They first charted on the Billboard Global 200 in 2020 with their single ‘Can't Stop Me’ and the Billboard Hot 100 in 2021 with their English-language release ‘The Feels.’ Itzy is the youngest active group of the four, debuting in 2019 under JYP Entertainment. They first entered the Billboard Global 200 in 2020 with their single ‘Not Shy’ and have charted three more times since with their singles ‘Mafia – In the Morning’, ‘Loco’, and ‘Sneakers.’

Lee (Reference Lee2004) marked one of the early linguistic studies of English use in K-pop by examining English as a third-party medium of communication facilitating transcultural flows between Korea and Japan. During a time of stringent censorship laws, English served as ‘a sociolinguistic breathing space for young South Koreans to construct identity and socially connect with others’ (p. 446). Ahn (Reference Ahn, Low and Pakir2021: 223) later revisited Lee's conclusions in the context of BTS's global success and argued that BTS employs English as a language of ‘fun, curiosity, and global connection’ rather than one of resistance or self-assertion. So as the market for K-pop expands from East Asia to a global audience, the implications of English language use change as well.

Jin (Reference Jin2016) argues that K-pop's internationalization has incentivized greater simplification and repetition in song lyrics, especially in the use of English. Lawrence (Reference Lawrence2010), through quantitative analysis, demonstrated that English borrowings into K-pop were most common in the hook and introduction, and less common in the verses. Moreover, Lawrence also extended the work of Lee (Reference Lee2004) pointing out that the most common themes of borrowed English words pertained to love and sex, serving as a ‘language of resistance against conservative Korean values’ (p. 11).

Yeo (Reference Yeo2018) analyzed the song titles, artist names, and lyrics of popular K-pop singles released from 1990 to 2017. From a theoretical position of ‘English as symbolic capital’ (Park & Wee, Reference Park and Wee2013), she proposed two dynamic processes in the global marketing of K-pop: moderation and reformulation. Yeo describes moderation as a careful balance between the use of English and Korean calibrated by multiple ideologies in shifting market conditions (p. 96). While producers may aim to incorporate more English into K-pop lyrics to reach international audiences, Korea remains an essential market for the consumption of K-pop. Yeo's other process, reformulation, involves the cultivation of a ‘nonnative’ brand of English unique to K-pop (English some label as ‘grammatically incorrect’ [Lawrence, Reference Lawrence2010] and ‘funny’ [Yoon, Reference Yoon2018]). While Yeo explored moderation of language use within song titles and artist names, little research has quantitatively examined the balance of English and Korean language use within lyrics. Moreover, this study will qualitatively examine the reformulation of a code ambiguation (CA) (Moody & Matsumoto, Reference Moody and Matsumoto2003; Lee, Reference Lee2022) within Itzy's debut single ‘DALLA DALLA.’

3. Methodology

This article employs mixed methods, coupling quantitative and qualitative analyses. Quantitatively, this study considered 77 songs released as singles by BTS (n = 33), BLACKPINK (n = 12), TWICE (n = 20) and Itzy (n = 12) from 2015 to 2022. Singles represent production companies’ strongest efforts to reach a broad audience, often serving as advance releases to upcoming albums. Of these singles, 12 tracks were excluded for featuring another artist, three tracks were excluded for having all-English lyrics, and four tracks were excluded for being Japanese-language releases. While the release of songs with all-English lyrics will be discussed later, this analysis considers only Korean-language releases, leaving 58 songs for analysis. Song lyrics and English translations were sourced from Color Coded Lyrics (CCL, 2023), a website that compiles Korean, romanized, and English translations of K-pop lyrics (Yeo, Reference Yeo2018).

After importing the Korean versions of each track's lyrics as .txt files and removing non-lyrical content (e.g., labels of which group member is singing), a Python script removed punctuation marks and converted all words to lowercase. Next, the script employed the py3langid package (Barbaresi, Reference Barbaresi2022) to label each word as either English or Korean based on transcribers’ orthographic choices. Finally, the script counted the number of tokens and types by language. The sum of all song data yielded 18,628 tokens and 8,034 types. Due to the repetitive nature of song lyrics (Seabrook, Reference Seabrook2015), especially for English in K-pop (Jin, Reference Jin2016), only types were considered for analysis. Counting the number of unique words in a text is more indicative of the complexity of language use than counting all words individually. Moreover, counting types reduces the weight of single, repetitive English filler words like ‘yeah,’ ‘uh’ or ‘oh’ common to K-pop songs (Lee, Reference Lee2004). This analysis accepted transcribers’ orthographic choices regarding which words to include in a song's lyrics and which scripts to use in representing those lyrics. Potential shortcomings of these methodological choices receive further consideration in Section 6.

Qualitatively, this analysis focuses on a single code ambiguation built into the title and hook of Itzy's debut single, ‘DALLA DALLA.’ In this article, code ambiguation (CA) indicates a word or phrase that can carry meaning in two languages (Moody & Matsumoto, Reference Moody and Matsumoto2003). Lee (Reference Lee2022) borrows from Luk (Reference Luk2013) who noted that CAs share an acoustic link (similar sound), and stand in either a parallel, complementary, or disjoint semantic relationship. Finally, recent K-pop cultural studies literature, journalistic articles, and other K-pop-focused media further contextualize this code ambiguation.

4. Quantitative analysis

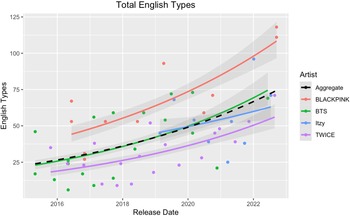

A linear regression model calculated in R predicted the percentage of English types as a function of release date. Dates were represented numerically in increments of years. Intercepts were set to 2019. Models were calculated for each group individually as well as in aggregate. Analyses showed statistically significant (p < 0.05 against a null hypothesis of slope = 0) positive correlations for tracks released by BTS (intercept = 0.409, slope = 0.088, p < 0.001), BLACKPINK (intercept = 0.445, slope = 0.061, p < 0.001), and TWICE (intercept = 0.272, slope = 0.057, p < 0.01). Itzy’s singles did not reach statistical significance (intercept = 0.370, slope = 0.019, p = 0.68). A statistically significant positive correlation was found in aggregate (intercept = 0.348, slope = 0.062, p < 0.001). This aggregate model predicted that the percent share of English types in these 58 songs would increase by about six percentage points each year from 2015 to 2022. These linear regression models relative to percentage of English types are visually summarized in Figure 1 below. Results suggest that the moderation threshold in these groups’ singles has reliably increased between 2015 and 2022. About half of songs released prior to 2018 (52.17%, n = 23) contain less than 20% English types. For songs released after 2020 (n = 21), however, only 2 songs (BTS: ‘Life Goes On’ and Itzy: ‘MIDZY’) fall below this 20% threshold.

Figure 1. Plot and linear models of the percentage of English types of 58 singles released by BTS, BLACKPINK, TWICE, and Itzy from 2015 to 2022

To show not only an increase in the proportion of English types, but also the use of English types overall, a Poisson regression model predicted the estimated number of English types in each song. A Poisson model of regression predicts an increase in count over a given interval (in this case, English types per year). Poisson models were offset by the logarithm of total types to help control for variation in total types between songs. For example, a log-1 Poisson coefficient of 1.149 for tracks released by TWICE indicates that the model predicts the total number of English types in TWICE singles to increase by about 14.9% each year. Like the linear regression models described above, Poisson regression analyses showed statistically significant positive correlations (p < 0.05 against a null hypothesis of log-1 (coefficient) = 1) for songs released by BTS (log-1 (coefficient) = 1.130, z-value = 6.913, p < 0.001), BLACKPINK (log-1 (coefficient) = 1.138, z-value = 8.459, p < 0.001), and TWICE (log-1 (coefficient) = 1.149, z-value = 6.948, p < 0.001), but not for Itzy (log-1 (coefficient) = 1.056, z-value = 1.259, p = 0.208). However, in aggregate, a statistically significant positive correlation was found (log-1 (coefficient) = 1.145, z-value = 14.79 p < 0.001). Poisson regression models of total English types are visually summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Poisson regression models for English types for 58 singles released by BTS, BLACKPINK, TWICE, and Itzy from 2015 to 2022

As shown in Figure 2, a substantial number of tracks (n = 12) released prior to 2018 contain less than 25 English types. On the other hand, among 21 songs released during or after 2020, only one song (BTS: ‘Life Goes On’) includes less than 25 English types. These results suggest that the rise in proportion of English types relative to Korean types also includes an increase in quantity of English types in these K-pop songs.

There are potential explanations for Itzy’s nonsignificant results. As the youngest group of the four (debuting in 2019), they also have the smallest sample size (n = 9). Moreover, their debut date coincides with BTS and BLACKPINK's sustained appearances on the Billboard Hot 100 and Global 200 charts. As a group debuting in the midst of K-pop's emerging post-global era, the median of their English type percentage (38.46%) and total types (53) is second only to BLACKPINK (43.79%, 59). In other words, Itzy debuted at a higher moderation threshold, a product of K-pop's rapidly shifting market conditions, and therefore had less room to grow in their proportional English use. The next section qualitatively discusses recent shifts in Itzy's use of English through a code ambiguation in their debut single ‘DALLA DALLA’.

5. Qualitative analysis – code ambiguation and reformulation

Moody and Matsumoto (Reference Moody and Matsumoto2003: 4) define ‘code ambiguation’ (CA) as ‘a form of language blending similar to code-mixing … [which produces] utterances that have potential meaning in both languages.’ Ahn (Reference Ahn, Low and Pakir2021) identified code ambiguation in the 2016 BTS song ‘Blood, Sweat, and Tears’ with the phrase manhi manhi manhi /mɐ.ni mɐ.ni mɐ.ni/. While Korean listeners may interpret this as an intensifier meaning ‘a lot, a lot, a lot’ or ‘very, very, very,’ English listeners may interpret this phrase as a ‘phonetic Koreanization’ (Ahn, Reference Ahn2018) of the phrase ‘money, money, money.’

Lee (Reference Lee2022) proposed a Korean-English CA typology borrowed from Luk (Reference Luk2013) where acoustic links at the phonetic level produce parallel, complementary, or disjoint relationships between languages at the semantic level. This means CAs may have similar meanings between language codes (parallel), require both languages to complete a code (complementary), or semantically unrelated meanings between language codes (disjoint).

One strong example of CA appears within the title and hook of Itzy's debut single, ‘DALLA DALLA.'

This phonetic realization of the Korean word dalla involves a striking schwa [ə] reduction in a context following an English line. Earlier in the hook, in a context more removed from English lyrics, the same word is phonetically realized with a low back vowel [ɐ].

Anglicized Korean seems more prevalent in the immediate environment of English lyrics (1), and often draws influence from AAL (Moon, Starr & Lee, Reference Moon, Starr and Lee2013; Anderson, Reference Anderson2020). In this case, the final vowel [ɐ] reduces to schwa [ə], creating near-homophones between the Korean words for ‘different’ and an AAL-derived non-rhotic pronunciation of ‘dollar.’ This r-less pronunciation of ‘dollar’ is well-attested in global pop music (e.g. Lucas, Reference Lucas1998; DOLLA, 2020).

This CA is not lost on YouTube interviewer JaeJae, who interviewed Itzy in 2021.

Pointing out that the Korean word ‘dalla’ (which means ‘different’) sounds similar to the English word ‘dollar,’ [JaeJae] asked, ‘To foreigners’ ears, wouldn't ‘DALLA’ sound like ‘dollar,’ as in the money? (Cha, Reference Cha2021)

Itzy member Ryujin went on to confirm this choice and further explain that the original title of their debut song was ‘Billion Dollar Baby,’ an intended double-entendre indexing a billion-times uniqueness in Korean listeners and wealth in English. The awareness of this double-entendre in the K-pop community is reinforced in a track released by fellow fourth-generation girl group (G)I-DLE (Korean: yeoja aideul) in 2018 titled ‘$$$ (Dalla)’.

At first glance, this CA appears disjointed as terms for ‘different’ and ‘U.S. currency’ seem divergent in their meanings. However, a reviewer pointed out the complementary relationship of this CA. JaeJae and Itzy's interview was conducted in Korean, ostensibly for a Korean audience, and international fans and media show little corresponding recognition of this CA. Korean-English code mixing does not simply map Korean to domestic and English to international listening subjects (Inoue, Reference Inoue2003). Rather, the acknowledgement of this double-meaning among Korean media sources and other K-pop groups suggests that the lyrical decision may intentionally index the cosmopolitan ideology of English (Park & Abelmann, Reference Park and Abelmann2004), but not serve as an (intentional) linguistic foothold for English language listeners.

Songwriters would later provide that foothold, however, as Itzy achieved more global recognition, and the group re-released ‘DALLA DALLA’ in an English language version in 2021. In this version, the previous CA seems to resolve itself toward the Korean word for ‘different.’

(3) presents an interesting linguistic question: should the preservation of Korean words in English versions of K-pop songs be considered Korean? (As English is considered English in Korean lyrics?) Or do these remnants serve as borrowed lexical items into an emerging register that Yeo (Reference Yeo2018: 108) refers to as K-pop English, or ‘non-native-like English in K-pop song lyrics.’

Popular song lyric websites differ on how they represent dalla in this English version: from Hangul (Musixmatch, 2021), to Romanized in all-caps (Genius, 2021), to Romanized in lowercase (Genie, 2021). These questions would be less interesting if the only words of Korean origin were the title itself. However, the English version of ‘DALLA DALLA’ also includes the Korean-derived terms ‘eonni’ (‘older sister’) and ‘malijima’ (‘Don't stop me.’) The former term is one of many Korean words common within the translingual practice of online K-pop communities (Crow, Reference Crow2019) and a simple YouTube search of ‘malijima’ reveals that this lyric was very popular among fans, which likely influenced its retention in the English re-release. This is also indicative of K-pop's culture of prosumerism (Toffler, Reference Toffler1980) as strong fan engagement with one lyric seems to have influenced its preservation in the English re-release. The concept of K-pop English as a language register is very recent, and Yeo's (Reference Yeo2018) examples of K-pop English involve syntactic divergences and English lexical substitutions as opposed to borrowing. Therefore, further analysis beyond the scope of this article is needed.

In sum, the English-language re-release of ‘DALLA DALLA’ at most reformulates the term dalla as a borrowing into an emerging register of K-pop English or at least resolves the code ambiguation in favor of the Korean meaning. Furthermore, the metalinguistic awareness of a Korean media outlet of this code ambiguation and limited acknowledgement by international K-pop fans complicates the notion that English language use necessarily indexes appeals to international listeners. In fact, the retention of Korean language words and phrases in the ‘English version’ of ‘DALLA DALLA’ suggests many international fans appreciate English and Korean code-mixing over monolingual English lyrics.

6. General discussion and conclusion

This study builds on previous qualitative analyses of English in K-pop lyrics by quantitatively investigating the prevalence of unique English words in K-pop songs by four internationally successful groups from 2015 to 2022. This eight-year span centers around the time groups like BTS and BLACKPINK began regularly charting on the Billboard Hot 100 – an index of popular singles in the U.S. This analysis shows that English use in these K-pop songs have expanded both in raw counts and in proportion to total types. It suggests that the Korean music industry continues to ‘appropriate English mixed into [its] lyrics to attract Western audiences’ (Jin, Reference Jin2016: 124). Moreover, this study qualitatively questions if a code ambiguation latent in the group Itzy's debut single ‘DALLA DALLA’ has undergone reformulation within the song's English re-release as the group develops a strong international fanbase.

These findings also align with Ahn (Reference Ahn, Low and Pakir2021) and Yeo (Reference Yeo2018) in arguing that the expansion of English use in K-pop reflects expansion into markets with listeners more familiar with the English language. Such English use reflects expanding ‘points of entry’ (Takacs, Reference Takacs2014) or a growing linguistic foothold that invites greater participation from non-Korean-language listeners. For example, one participant in Yoon's (Reference Yoon2018) study of Canadian K-pop fans mentions that ‘because international fans like [themselves] don't look up the lyrics, they'll know [those] sentences in English. Those are the part of the song that they'll sing’ (Yoon, Reference Yoon2018: 7). In an interview with MTV, Itzy member Yuna mirrors this point, saying, ‘artists can have a new experience recording English versions, and fans can enjoy and understand the lyrics more too’ (Francis, Reference Francis2021).

Moderation remains important for K-pop producers, both to balance a cosmopolitan ethos among local Korean listeners and to present a distinctly Korean persona abroad. As another Canadian K-pop fan commented, ‘I enjoy the catchy, fun, and refreshing melodies and lyrics incorporating many different genres of music. This diversity in combining many forms of music I find to be extremely refreshing as opposed to much of Western pop music’ (Jin, Reference Jin2016: 128).

Due to length requirements, this article has not further detailed another key observation in the internationalization of K-pop – the proliferation of original all-English tracks and the re-release of English versions of Korean-language songs. Itzy has released English versions of most of their title tracks (eight of the nine tracks analyzed in this study). In an interview with Forbes magazine, Itzy member Lia explains why.

We don't only have fans in Korea . . . We are growing globally. I think it's a big part of our growth and success . . . I know [fans] still love us with Korean music, but it's different hearing it in English (McIntyre, Reference McIntyre2021).

In an interview with Rolling Stone, member Chaeryeong also commented that ‘making English versions of [their] songs is a new communication method for [them]’ (Chan, Reference Chan2021).

While this study takes a first step towards a more aggregated quantitative approach to Yeo's concept of moderation, some lyrics were less categorizable than others. For example, analysis of BLACKPINK's 2018 single ‘Ddu-du Ddu-du’ revealed 15 tokens of ‘du’ and 10 tokens of ‘ddu.’ These oft-repeated title tokens that onomatopoetically iconize gunfire were written in Roman script, but their status as tokens of English is dubious. The same goes for common tokens that can serve as filler words in either English or Korean like ‘uh’. However, by focusing on types rather than tokens, multiple tokens of questionable language assignment collapses to single English types, thereby mitigating confounding effects. Also, a limited number of tokens morphologically code-mix English lexemes with Korean grammatical particles written in Hangul within a single word (e.g., ‘volume-은[eun]’ in BLACKPINK, ‘Ddu-du Ddu-du’). The Python script would code this token as English, but one could argue for splitting these into two tokens and coding both for each language respectively. Fortunately, these examples were sparse. While the coding of English and Korean tokens was admittedly blunt, this analysis opts to treat transcribers’ choices to privilege English orthography as significant within this article's overall argument for K-pop's accelerating globalization (Garza, Reference Garza2021).

Also, it is important to recontextualize this study by admitting that lyrics have a reduced and dwindling role in K-pop. ‘This could be blamed on the artificiality of the genre’ and that ‘idols themselves usually have little chance to apply themselves in the lyrics of their songs’ (Jin, Reference Jin2016: 129). Instead, many scholars associate K-pop's growing global appeal to its polished performances (Yeo, Reference Yeo2018), appeals to fantasy and desire (Lee, Reference Lee2012) and the dynamic hybridization of diverse cultural artifacts (Jin, Reference Jin2016; Garza, Reference Garza2021). However, whether lyrics are of priority to K-pop consumers or not, their lingering linguistic footprints remain interesting to language scholars.

Quantitative data in this study suggest a change-in-progress, so future work will continue tracking the English use of these four groups along with fourth-generation groups who have since broken through the six-million Spotify listener threshold in the past year including (G)I-DLE, Stray Kids, and TOMORROW X TOGETHER. This emergent pattern also invites a replication of Lawrence (Reference Lawrence2010). Have patterns of English use within song verses shifted as well? Finally, future work can extend Chun (Reference Chun2017) by comparing fans’ metalinguistic commentary of Korean language and English language releases of the same K-pop tracks on YouTube. Such an analysis could better uncover the ideological stances of international K-pop fans as ‘listening subjects’ (Inoue, Reference Inoue2003).

In an interview with MTV, Itzy member Yeji commented with a laugh that ‘English is confidence’ (Francis, Reference Francis2021). Itzy also released their first original English-language single, ‘Boys Like You’, in 2022, suggesting that for K-pop producers, English is currency.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to a global community of colleagues, without whom this article would not be possible. I would like to thank my advisor, Jennifer Cramer, for her insightful feedback and advice through the journal submission process, as well as Josef Fruehwald for helping me refine my statistical models. I would also like to thank Seongyong Lee, Yeo Rei-Chi Lauren, Joyhanna Yoo Garza, and Rusty Barrett for their helpful feedback. Finally, the anonymous reviewers challenged me to refine and clarify my ideas through incisive yet illuminating criticism, for which I am grateful. All remaining errors are mine.

IAN SCHNEIDER is an M.A. student of Linguistics at the University of Kentucky. He received his B.A. in Linguistics from the University of Kentucky. His research interests include language ideologies, language and place, English education, and English as a lingua franca. He has also worked as a teacher educator in the South Jeolla province of South Korea. His specialties there included listening, speaking, and communication skills as well as flipped learning pedagogy. Email: [email protected]

IAN SCHNEIDER is an M.A. student of Linguistics at the University of Kentucky. He received his B.A. in Linguistics from the University of Kentucky. His research interests include language ideologies, language and place, English education, and English as a lingua franca. He has also worked as a teacher educator in the South Jeolla province of South Korea. His specialties there included listening, speaking, and communication skills as well as flipped learning pedagogy. Email: [email protected]