Introduction

Externalizing psychopathology refers to a broad spectrum of overt, outwardly manifested symptoms such as disinhibition, antagonism, attentional problems, hyperactivity, and substance use problems (Ruggero et al., Reference Ruggero, Kotov, Hopwood, First, Clark, Skodol, Mullins-Sweatt, Patrick, Bach, Cicero, Docherty, Simms, Michael Bagby, Krueger, Callahan, Chmielewski, Conway, Clercq, Dornbach-Bender and Zimmermann2019). Although externalizing psychopathology is stable, thereby showing homotypic continuity (e.g., Bufferd et al., Reference Bufferd, Dougherty, Carlson, Rose and Klein2012; Lahey et al., Reference Lahey, Pelham, Loney, Lee and Willcutt2005), its expression also changes across development and it predicts internalizing psychopathology, thereby also demonstrating substantial heterotypic continuity (e.g., Beauchaine et al., Reference Beauchaine, Zisner and Sauder2017). For children, externalizing symptoms typically include hyperactivity, aggression, and rule breaking at home or school (Achenbach & Edelbrock, Reference Achenbach and Edelbrock1991; Beauchaine et al., Reference Beauchaine, Zisner and Sauder2017). When such behaviors are persistent, cause impairment, and are developmentally excessive, diagnoses of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD), or Conduct Disorder (CD) may be warranted. Externalizing symptoms have serious implications for youth adjustment, given that they are linked to negative outcomes including lower educational attainment, teen parenthood, and incarceration (Beauchaine et al., Reference Beauchaine, Zisner and Sauder2017; Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Foster, Saunders and Stang1995, Reference Kessler, Berglund, Foster, Saunders, Stang and Walters1997). However, externalizing behavior is, to some degree, virtually ubiquitous in childhood and oftentimes does not persist into adolescence or adulthood (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Shaw and Gilliom2000; Lahey et al., Reference Lahey, Lee, Sibley, Applegate, Molina and Pelham2016). Understanding which children are at greatest risk for persistent externalizing problems is crucial for early identification and intervention.

Both temperamental and environmental factors contribute to the persistence of externalizing symptoms through complex, interactive processes. Child impulsivity, which refers to immediate responsiveness to rewards and low inhibition (Ahadi & Rothbart, Reference Ahadi, Rothbart, Halverson, Kohnstamm and Martin1994; Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Spinrad and Morris2002), is a heritable, stable aspect of temperament and personality (Ahmad & Hinshaw, Reference Ahmad and Hinshaw2018; Tiego et al., Reference Tiego, Chamberlain, Harrison, Dawson, Albertella, Youssef, Fontenelle and Yücel2020). Individuals with high trait impulsivity show a preference for immediate rewards over greater delayed rewards, act without forethought, have difficulty planning, and have low self-control (Beauchaine et al., Reference Beauchaine, Zisner and Sauder2017). Impulsivity is a transdiagnostic vulnerability factor for externalizing psychopathology (Ahmad & Hinshaw, Reference Ahmad and Hinshaw2018; Jiménez-Barbero et al., Reference Jiménez-Barbero, Ruiz-Hernández, Llor-Esteban and Waschgler2016; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Eisenberg, Valiente and Spinrad2016); specifically, while it is a hallmark of ADHD, it also renders individuals vulnerable to other externalizing psychopathology and other behavior problems throughout the lifespan (Ahmad & Hinshaw, Reference Ahmad and Hinshaw2018; Jiménez-Barbero et al., Reference Jiménez-Barbero, Ruiz-Hernández, Llor-Esteban and Waschgler2016). Considering environmental influences, both positive (e.g., positive affect, warmth, acceptance) and negative parenting practices (e.g., parental control, harshness, inconsistency) have been studied extensively in the context of developmental psychopathology (Kiff et al., Reference Kiff, Lengua and Zalewski2011; McLeod et al., Reference McLeod, Weisz and Wood2007), including externalizing problems. Higher parent positive affectivity is associated with lower externalizing psychopathology in offspring (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Eisenberg, Valiente and Spinrad2016), potentially mediated by children’s own emotion regulation (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Valiente, Morris, Fabes, Cumberland, Reiser, Gershoff, Shepard and Losoya2003; Eisenberg, Losoya, et al., Reference Eisenberg, Losoya, Fabes, Guthrie, Reiser, Murphy, Shepard, Poulin and Padgett2001; Eisenberg, Thomson Gershoff, et al., Reference Eisenberg, Thomson Gershoff, Fabes, Shepard, Cumberland, Losoya, Guthrie and Murphy2001). Hostile, or harsh, parenting, as well as parenting that lacks structure, may have their own independent negative impacts on child outcomes; for example, Xu et al. (Reference Xu, Farver and Zhang2009) observed that harsh parenting practices were associated with child proactive and reactive aggression and unstructured caregiving appears related to externalizing psychopathology as well (Jacobvitz et al., Reference Jacobvitz, Hazen, Curran and Hitchens2004; Kerig, Reference Kerig2005; Shaffer & Sroufe, Reference Shaffer and Sroufe2005). Wiggins et al. (Reference Wiggins, Mitchell, Hyde and Monk2015) observed that the pattern of harsh parenting throughout childhood also impacted the development of child externalizing problems over time; in particular, elevated and increasing harsh parenting predicted elevated, stable externalizing symptoms in children.

However, developmental psychopathology is characterized by dynamic interplay between endogenous and exogenous factors such that main effects of caregiving on children’s externalizing symptom development are moderated by child characteristics, including trait impulsivity. Specifically, impulsive children may be more vulnerable to the impact of negative parenting (Ahmad & Hinshaw, Reference Ahmad and Hinshaw2018; Hentges et al., Reference Hentges, Shaw and Wang2018; Kiff et al., Reference Kiff, Lengua and Zalewski2011). In seminal research, Patterson (Reference Patterson1986) described a model through which ineffective parental discipline interacts with child behavior to produce negative parent-child interactions in which child externalizing behavior is negatively reinforced. These coercive parent–child interactions ultimately increase oppositional behavior and conduct problems in children (Patterson, Reference Patterson2016; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Dishion, Shaw, Wilson, Winter and Patterson2014). In line with this model, some of the most supported interventions for reducing child behavior problems involve parent management training. For instance, the Parent Management Training—Oregon Model involves reducing coercive interactions and promoting positive parenting, including skill encouragement, limit setting, monitoring/supervision, interpersonal problem solving, and positive involvement (Forgatch & Kjøbli, Reference Forgatch and Kjøbli2016). Studies have shown support for the efficacy and effectiveness of this intervention for decreasing child behavior problems (Forgatch & DeGarmo, Reference Forgatch and DeGarmo2011; Sigmarsdóttir et al., Reference Sigmarsdóttir, Degarmo, Forgatch and Gumundsdóttir2013). In addition, consistency in discipline is an effective component of interventions for children with ADHD (Wyatt Kaminski et al., Reference Wyatt Kaminski, Valle, Filene and Boyle2008).

In addition to treatment studies, descriptive, longitudinal research further supports dynamic interactions between child characteristics and parenting in predicting child externalizing psychopathology. Hentges et al. (Reference Hentges, Shaw and Wang2018) found that child impulsivity at age 2 and rejecting parenting interacted to predict aggression in adolescence and adulthood, such that rejecting parenting predicted greater aggression at ages 12, 15, and 22 only when children were high in impulsivity. The impact of impulsivity and parenting on child externalizing symptoms seems most consistent with a vulnerability model (cf. differential susceptibility), whereby children with high impulsivity are at risk for developing externalizing problems in the context of certain parenting practices (Slagt et al., Reference Slagt, Semon Dubas and Van Aken2015). Related constructs, such as hyperactivity and low effortful control, also render children more vulnerable to parental hostility and negative discipline (Morris et al., Reference Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Sessa, Avenevoli and Essex2002; Patterson et al., Reference Patterson, DeGarmo and Knutson2000). Overall, research suggests that children who are impulsive, sensation-seeking, or who show poor self-regulation tend to benefit the most from parenting that is high in control/structure (Rubin et al., Reference Rubin, Hastings, Chen, Stewart and McNichol1998; Stice & Gonzales, Reference Stice and Gonzales1998; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Farver and Zhang2009), but also sensitive (Bakermans-Kranenburg & Van Ijzendoorn, Reference Bakermans-Kranenburg and Van Ijzendoorn2006) and not harsh (Leve et al., Reference Leve, Kim and Pears2005; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Farver and Zhang2009).

Parenting variability and range as a predictor of externalizing psychopathology

Most research on parenting and children’s externalizing psychopathology has focused on average or “typical” parenting aggregated across different contexts, despite evidence that variable or inconsistent caregiving may also play an important role in child psychopathology (Barry et al., Reference Barry, Dunlap, Lochman and Wells2009; Li & Lansford, Reference Li and Lansford2018). For example, inconsistent discipline (Patterson, Reference Patterson1986) is linked to child externalizing symptoms, including aggression and attention problems (Barry et al., Reference Barry, Dunlap, Lochman and Wells2009; Lengua et al., Reference Lengua, Wolchik, Sandler and West2000); in previous research (Brody et al., Reference Brody, Murry, Ge, Kim, Simons, Gibbons, Gerrard and Conger2003; Edens et al., Reference Edens, Skopp and Cahill2008), inconsistent discipline has included components of parental hostility (i.e., harsh discipline) and parenting structure (i.e., the extent to which parent-child roles remain clearly defined across contexts through the use of consistent rules and discipline).

While variability in parenting over time is generally positively associated with child psychopathology (Fosco et al., Reference Fosco, Mak, Ramos, LoBraico and Lippold2019; Fosco & Lydon-Staley, Reference Fosco and Lydon-Staley2020), variation in caregiving that reflects parent flexibility is generally negatively associated with child psychopathology (Hollenstein et al., Reference Hollenstein, Granic, Stoolmiller and Snyder2004). Fosco et al. (Reference Fosco, Mak, Ramos, LoBraico and Lippold2019) found that lability of parent-adolescent connectedness, conceptualized as day-to-day fluctuation, predicted offspring psychopathology, including antisocial behavior and substance use. Lability in parenting practices was also associated with alcohol use. Lippold et al. (Reference Lippold, Fosco, Hussong and Ram2019) also found that greater lability in parents’ warmth and hostility were associated with increased delinquency and substance use initiation in youth. Hollenstein and colleagues constructed state space grids to map the positive and negative engagement of a caregiver-child dyad (Granic & Hollenstein, Reference Granic and Hollenstein2003; Hollenstein et al., Reference Hollenstein, Granic, Stoolmiller and Snyder2004; Hollenstein & Lewis, Reference Hollenstein and Lewis2006), finding associations between rigidity in parent-child interactions and later child externalizing behavior.

However, the aforementioned research did not examine whether children’s externalizing outcomes varied as a function of their trait impulsivity, even though associations between parenting variability and child outcomes may be particularly strong for children with high impulsivity (Lengua et al., Reference Lengua, Wolchik, Sandler and West2000; Patterson et al., Reference Patterson, DeGarmo and Knutson2000). Neural correlates of high impulsivity in childhood may increase children’s vulnerability to externalizing disorders by decreasing the time frame in which reward contingencies can be learned (Zisner & Beauchaine, Reference Zisner, Beauchaine, Beauchaine and Hinshaw2016); as a result, impulsive children benefit from frequent, consistent feedback and immediate reinforcers (Sagvolden et al., Reference Sagvolden, Johansen, Aase and Russell2005). Having caregiving that is consistent (i.e., low variability in caregiving across settings) may therefore be particularly beneficial for these children.

Concerning additional gaps in knowledge, although parenting variability seems important to childhood externalizing problems, there is less relevant research overall and studies of parenting variability have varied widely in their methodology and findings, rendering it challenging to draw conclusions regarding the relations between constructs. Li and Lansford (Reference Li and Lansford2018) used ecological momentary assessment (EMA) to examine daily variation in parental affect, finding that variability in parent positive affectivity was linked to child ADHD symptoms. There is also evidence that, in some cases, low parenting variability (i.e., rigidity) may be detrimental, although this may depend on whether it is the mother or father interacting with the child (Lunkenheimer et al., Reference Lunkenheimer, Olson, Hollenstein, Sameroff and Winter2011).

Most relevant studies (Barry et al., Reference Barry, Dunlap, Lochman and Wells2009; Li & Lansford, Reference Li and Lansford2018; Lunkenheimer et al., Reference Lunkenheimer, Olson, Hollenstein, Sameroff and Winter2011) have either used self-report measures or a single observed context to assess caregiving variability. However, standardized observational measures of parenting across contexts that vary in situational “press” for different caregiver behaviors (e.g., free-play versus structured tasks) are particularly well-suited to assessing caregiving range, given that they standardize caregiving contexts across participants and do not rely on caregiver insight (e.g.. Zaslow et al., Reference Zaslow, Gallagher, Hair, Egeland, Weinfield, Ogawa, Tabors and De Temple2006). The inclusion of several behavioral tasks allows for more variety in parent behavior and affectivity, thereby better capturing the range of caregiving across situations.

Current study and hypotheses

Thus, most work on caregiving and children’s externalizing psychopathology development (Barry et al., Reference Barry, Dunlap, Lochman and Wells2009; Li & Lansford, Reference Li and Lansford2018; Lunkenheimer et al., Reference Lunkenheimer, Olson, Hollenstein, Sameroff and Winter2011) has used single, brief tasks, or parent-reported caregiving to assess characteristic caregiving. Additionally, the bulk of past research on this topic has not integrated child factors, such as impulsivity, that render some children more vulnerable to inconsistent caregiving than others, nor has it considered range in caregiver practices. We therefore examined how child impulsivity and early parenting impacted the development of children’s externalizing symptoms in early and middle childhood, a time when children typically become more cooperative and compliant (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Shaw and Gilliom2000; Hatoum et al., Reference Hatoum, Rhee, Corley, Hewitt and Friedman2018; Lahey et al., Reference Lahey, Lee, Sibley, Applegate, Molina and Pelham2016); children delayed in this normative decrease may be at especially high risk for future, more serious externalizing psychopathology (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Shaw and Gilliom2000). Based on previous findings, we formulated the following hypotheses:

-

1. Given past work implicating low parent positive affectivity in children’s externalizing problems (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Valiente, Morris, Fabes, Cumberland, Reiser, Gershoff, Shepard and Losoya2003; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Eisenberg, Valiente and Spinrad2016), we hypothesized that greater mean caregiver positive affectivity would predict lower initial externalizing symptoms and a steeper decline in these symptoms during middle childhood.

-

2. Given findings on negative discipline and harsh parenting (Wiggins et al., Reference Wiggins, Mitchell, Hyde and Monk2015; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Farver and Zhang2009), we hypothesized that greater mean caregiver hostility would predict higher initial externalizing symptoms and a less steep decline in these symptoms during middle childhood.

-

3. Given past research on parenting structure (Jacobvitz et al., Reference Jacobvitz, Hazen, Curran and Hitchens2004; Kerig, Reference Kerig2005; Shaffer & Sroufe, Reference Shaffer and Sroufe2005), we hypothesized that more structured caregiving would predict lower initial externalizing symptoms and a steeper decline in these symptoms during middle childhood.

-

4. Based on findings that children with high impulsivity or ADHD may be more sensitive than other children to the impacts of negative parenting (Kiff et al., Reference Kiff, Lengua and Zalewski2011), and that these children benefit from parenting that is sensitive, structured, and not harsh (Bakermans-Kranenburg & Van Ijzendoorn, Reference Bakermans-Kranenburg and Van Ijzendoorn2006; Rubin et al., Reference Rubin, Hastings, Chen, Stewart and McNichol1998; Stice & Gonzales, Reference Stice and Gonzales1998; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Farver and Zhang2009), we hypothesized that the aforementioned effects would be more pronounced for children higher in impulsivity.

-

5. There is less research on caregiver range and its influence on children’s externalizing symptoms. Due to the mixed findings on parenting variability in general (Lunkenheimer et al., Reference Lunkenheimer, Olson, Hollenstein, Sameroff and Winter2011), and lack of research on parent positive affectivity range in particular, we did not have specific hypotheses regarding the directions of these effects. However, given the studies showing that inconsistent discipline is associated with child externalizing symptoms (Barry et al., Reference Barry, Dunlap, Lochman and Wells2009; Patterson, Reference Patterson1986), we hypothesized that a greater range in caregiver hostility and parenting structure would both predict higher initial externalizing symptoms and a less steep decline in these symptoms during middle childhood.

We tested these research questions using a large sample of children who were assessed at ages 3, 5, 8, and 11. Children’s impulsivity was assessed observationally, given that lab-based measures of impulsivity have strong predictive validity for later externalizing behavior (e.g., Olson et al., Reference Olson, Schilling and Bates1999). To examine “typical” (i.e., average) parenting and range in parenting, since studies suggest that observed caregiving is a greater and more consistent predictor of children’s outcomes than questionnaire measures (e.g.. Zaslow et al., Reference Zaslow, Gallagher, Hair, Egeland, Weinfield, Ogawa, Tabors and De Temple2006), we used observer ratings of parent–child interactions during three different tasks designed to elicit a range of caregiver and child behaviors.

Method

Participants

A sample of 409 children (208 girls, M age = 3.43 at Time 1) and their primary caregivers (93% mothers) completed the study. We recruited participants through a university participant pool, online advertisements, and flyers placed in local daycares, preschools, and recreational facilities in the London, Ontario area. We screened children for cognitive ability using the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT), and the sample showed typical performance. This test was used as a measure of general cognitive ability, to increase the representativeness of the sample and external validity of the findings. We excluded children who had serious medical or psychological conditions, as determined by a trained research assistant; during screening, parents were asked whether their child had ever received a diagnosis of a medical or psychological problem and several potential participants were excluded due to a diagnosis of a developmental disability. Children (51% girls) were from primarily White families (93.4%). Both child impulsivity data and observed parenting data were collected when children were 3 years old. Externalizing symptom data were collected at four timepoints, when children were approximately 3 (N = 405), 5 (N = 379), 8 (N = 364), and 11 (N = 249) years old. This study was approved by the Western University Nonmedical Research Ethics Board.

Measures

Child behavior checklist

We assessed child externalizing symptoms using the externalizing problems subscale of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Edelbrock, Reference Achenbach and Edelbrock1991) as reported by the primary caregiver (93% mothers). This 33-item scale asks caregivers to rate their child’s aggressive and rule-breaking behaviors (e.g., cruel to animals; breaks rules at home, school, or elsewhere) on a 3-point scale (0 = absent, 1 = occurs sometimes, 2 = occurs often). Caregiver ratings of child externalizing symptoms were obtained at each assessment time point. Internal consistency was excellent at Times 1, 3, and 4, and acceptable at Time 2 (T1 α = .97, T2 α = .72, T3 α = .94, T4 α = .93).

Observed parenting

We assessed parent positive affectivity (PPA; 3-point scale; e.g., consistently smiling/laughing), parent hostility (5-point scale; e.g., frequent use of a harsh/negative tone), and poor parenting structure (7-point scale; e.g., appearing uncomfortable imposing limits) through three separate caregiver–child interaction tasks at age 3 that were video recorded for future coding by trained raters. One of the tasks, the teaching task, was completed at a lab visit approximately 2 weeks prior to a home visit during which the remaining two tasks, the three-bag and prohibition tasks, were completed. We derived parenting dimensions and scoring guidelines from manuals for rating caregiver–child interactions (Egeland et al., Reference Egeland, Weinfield, Hiester, Lawrence, Pierce and Chippendale1995; Weinfield et al., Reference Weinfield, Egeland and Ogawa1997). Trainees underwent a training process in which their ratings were compared to experienced “master” coders on five children’s videos until achieving intraclass correlations ≥.80. We assessed inter-rater reliability for a subset of videos (15%) as an ongoing reliability check to reduce coder drift. Reliabilities for each parenting dimension ranged from moderate-to-good for the three-bag task (PPA: ICC = 0.77, N = 84; hostility: ICC = 0.81, N = 84; poor structure: ICC = 0.78, N = 84), the teaching task (PPA: ICC = 0.66, N = 69; hostility: ICC = 0.64, N = 69; poor structure: ICC = 0.69, N = 69), and the prohibition task (PPA: ICC = 0.62, N = 65; hostility: ICC = 0.67, N = 65; poor structure: ICC = 0.80, N = 65).

Average parenting scores were calculated based on the average rating of each parenting dimension across the three tasks. Range of parenting was modeled as a latent difference score based on each parent’s highest and lowest scores from the parenting tasks. To best conceptualize range across each dimension, we used highest and lowest scores regardless of the specific task from which they came (see Table A1 for the frequencies of the tasks used to generate the latent difference scores).

Three-bag task

This naturalistic task, based on a protocol by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (1997) and modified by Ispa et al. (Reference Ispa, Fine, Halgunseth, Harper, Robinson, Boyce, Brooks-Gunn and Brady-Smith2004), entailed the primary caregiver and child playing with three bags of toys for approximately 10 min. The first bag contained a book, the second contained a set of toy kitchen items, and the third bag contained a farmhouse play set.

Prohibition task

The prohibition task was designed to elicit negative child behavior. In this task, the primary caregiver and child were presented with two boxes of toys; one box contained fun and appealing toys (e.g., a toy electric guitar), while the other contained toys that were broken, had pieces missing, or were boring and age-inappropriate (e.g., a plastic cone, pieces for Mr. Potato Head without the head). The caregiver was instructed to prevent the child from playing with the appealing toys (3 min). After this time, the caregiver was instructed to allow the child to play with any of the toys (6 min). Finally, the caregiver was to instruct the child to clean up (5 min). The instructions were provided to the caregiver on printed instruction cards to make it appear that the instructions were coming from the caregiver.

Teaching task

The teaching task was based on the Teaching Tasks Battery (Egeland et al., Reference Egeland, Weinfield, Hiester, Lawrence, Pierce and Chippendale1995). In this task, the caregiver and child were presented with a challenging puzzle to work on together (5 min). The experimenter provided cards, showing six different ways the puzzle could be completed. Participants were instructed to place the cards for completed puzzles at the top corner of the desk, to show how many they had completed.

Laboratory assessment battery

During a 2.5-hr laboratory visit, children completed 12 tasks drawn from the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery (Lab-TAB; Goldsmith et al., Reference Goldsmith, Reilly, Lemery, Longley and Prescott1995). These tasks were video recorded and rated by trained coders in the lab using the same training procedures and reliability assurance as we did for the parenting task coding. Trainees underwent a training process in which their ratings were compared to experienced “master” coders on approximately 20 children’s videos until achieving intraclass correlations ≥.80. Child impulsivity can vary based on situational context (Tsukayama et al., Reference Tsukayama, Duckworth and Kim2013), and researchers have stated the importance of capturing impulsivity across situations (Olson et al., Reference Olson, Schilling and Bates1999); therefore, this global rating was aggregated across episodes to derive an impulsivity score based on child behavior in different contexts (see below).

Risk room

The experimenter let the child into a room containing novel and ambiguous objects: a small staircase, a mattress, a balance beam, a Halloween mask, a cloth tunnel, and a large, black cardboard box. The experimenter told the child to play with the objects “however you like,” and left the room for 5 min. Upon returning, she asked the child to interact with each of the objects.

Tower of patience

The child took turns with the experimenter stacking blocks to build a tower. Each time it was her turn, the experimenter waited an increasing delay before stacking her block.

Puzzle with parent (teaching task)

See the description of the teaching task above.

Stranger approach

The experimenter left the room after saying she had to retrieve a toy, and the child was left alone. An unfamiliar male research assistant entered the room and spoke to the child, following a script while moving closer at specified intervals. The research assistant asked the child four standardized questions and then left the room. The experimenter then returned. Finally, the male research assistant returned and the experimenter introduced him as her friend.

Car go

The child and experimenter raced remote control cars. The experimenter allowed the child to win every time.

Transparent box

The child chose a toy and the experimenter locked it in a transparent box. The child was given a set of keys, none of which were able to open the box, and the experimenter left for several minutes. The experimenter then returned with the correct key and the child was able to access the toy.

Pop-up snakes

The experimenter gave the child a canister which appeared to contain potato chips but actually contained coiled spring snakes. The experimenter demonstrated the trick, and then encouraged the child to use it to surprise their caregiver.

Jumping spider

The child and experimenter were seated at a table in the centre of the room. A research assistant brought in a terrarium containing a fuzzy, black, toy spider and placed it on the table. The experimenter showed the child the spider and encouraged the child to touch it. When the child’s hand was close to the spider, the experimenter manipulated the spider using an attached wire, making the spider jump. This was repeated four times, with the experimenter encouraging the child to touch the spider each time. Afterwards, the experimenter showed the child that the spider was a toy.

Snack delay

The child was told to wait until the experimenter rang a bell before eating a bite of a snack. The experimenter waited to ring the bell, based on a series of varied delays.

Impossibly perfect green circles

The child was asked to draw a perfect green circle on a large piece of paper. After each attempt, the experimenter lightly criticized the circle. After 2 min of attempts, the experimenter praised the child’s circles.

Popping bubbles

The child and experimenter played with a bubble-shooting toy for several minutes. The experimenter was enthusiastic and encouraging throughout the task.

Box empty

The child was given a gift-wrapped box and led to believe there was an appealing toy inside. The experimenter left the child alone for brief interval to discover the box was empty. The experimenter then returned with toys and told the child she forgot to place the toys inside.

Impulsivity coding

For each Lab-TAB episode, child impulsivity was rated on a three-point scale (low, moderate, and high) based on the child’s tendency to respond and/or act without reflection. This global rating was aggregated across episodes to derive a single impulsivity score based on child behavior across the entire lab visit. The impulsivity scale showed acceptable inter-rater reliability and moderate internal consistency (ICC = .74, N = 18; α = .76, N = 12).

Analyses

We performed initial analyses and data cleaning using RStudio, version 1.4.1106 (RStudio Team, 2020). We used multilevel regression models in MPlus, with the Bayesian estimator (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén1998–2021),Footnote 1 to predict child externalizing symptoms, with child age nested within participant. The model equations can be found in the Supplemental Material. Models were estimated employing MPlus default model priors. We subtracted 3.43 years (i.e., the mean age at Time 1) to fix the intercept at Time 1. We entered the mean child age at a given timepoint to any participants missing data at that timepoint (one child’s age at the time of testing was missing, so their age was entered as the mean age for that timepoint), then handled missing CBCL data using the full information maximum likelihood estimation procedure. At the within-participants level, we regressed child externalizing symptoms on participant age, and included random slopes representing the symptom change as children aged. At the between-participants level, parenting and temperament variables were included as predictors of externalizing symptom intercepts and slopes. We constructed multilevel models for each parenting dimension; each model included child impulsivity, the mean parenting rating on the relevant dimension, parenting range on the relevant dimension, and the interaction between child impulsivity and parenting average and range (Figure 1). Range of parenting was modeled as a latent difference score based on each parent’s highest and lowest scores from the parenting tasks; this approach has the advantage of modeling the difference within the estimated model. No covariates were included in the models, although treating child sex as a covariate in analyses not presented here did not substantially change any findings (results available from the first author upon request).

Figure 1. Model testing mean parenting, parenting range, child impulsivity, and their interactions in predicting children’s externalizing symptoms.

One child was excluded from analyses due to missing parenting data and another was excluded due to missing CBCL data at all waves. Other missing data were due to the caregiver not completing the CBCL at one or more timepoints (Time 1: N = 2; Time 2: N = 28; Time 3: N = 43; Time 4: N = 158). All participants’ data were included for the timepoints they completed. To examine the impact of missing data, we used t-tests to compare participants who completed the CBCL at all waves of data collection to those who had missing data at one or more timepoints. These groups did not differ in child externalizing symptoms at any of the timepoints (all ps > .12). They also did not differ on any of the mean parenting scores, nor any of the parenting range scores (all ps > .14). The groups did not differ in child age at Time 1, child sex, PPVT scores, nor child race (all ps > .09). Impulsivity was higher (t(405) = 1.99, p = .05) and family income was lower (t(386) = −2.08, p = .04) in those with missing data at one or more timepoints.

Results

Correlations between major study variables

We first examined bivariate correlations between key study variables (Table 1). Child externalizing symptoms at each timepoint were positively associated with all other timepoints. Mean hostility and Time 2 symptoms were unrelated; otherwise, child impulsivity, mean parent hostility, and mean parenting structure were positively associated with child externalizing symptoms. Child age at Time 1, PPVT score, and family income were all negatively associated with child externalizing symptoms, with the exceptions of child age at Time 1 and symptoms at Time 3, and PPVT score and symptoms at Time 2. Child impulsivity was positively associated with mean parent hostility, mean parenting structure, and hostility range, and negatively associated with child age at Time 1. Boys were higher in impulsivity than girls. Mean PPA was positively associated with PPVT score, and family income, and negatively associated with mean parent hostility and hostility range. Mean parent hostility was positively associated with mean structure and hostility range, and negatively associated with child age at Time 1, PPVT score, and family income. Mean parenting structure was positively associated with structure range, and negatively associated with child age at Time 1, and PPVT score. Parenting structure range was positively associated with child age at Time 1. Finally, PPVT scores were positively associated with family income.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and correlations between key variables

Note. *p < .05; **p < .01. CBCL EXT = Child Behavior Checklist externalizing subscale; PPA = parent positive affectivity; PPVT = Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test; Sex of child: boys = 0, girls = 1; Family income binned: 1 = <$20,000, 2 = 20,000–40,000, 3 = 40,001–70,000, 4 = 70,001–100,000, 5 = >100,000.

Multilevel models

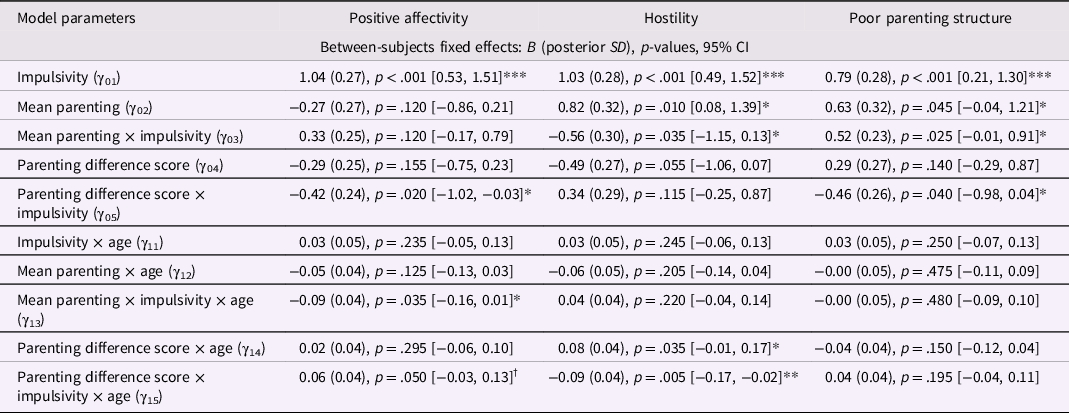

Results from the multilevel models are in Table 2.

Table 2. Mean parenting, parenting variability, and impulsivity predict child externalizing symptoms

Note. † p < .10; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001. SD = standard deviation. CI = credible interval.

Parent positive affectivity

In the model with PPA, lower child impulsivity (γ01) predicted fewer child externalizing symptoms at age 3. Neither mean PPA (γ02) nor its interaction with impulsivity (γ03) predicted child externalizing symptoms at age three. Range in PPA (γ04) did not predict child externalizing symptoms at age three; however, its interaction with impulsivity (γ05) did, such that greater PPA range was associated with fewer child externalizing symptoms for children higher in impulsivity. Child impulsivity (γ11) did not predict change in child externalizing symptoms. Mean PPA (γ12) also did not predict change in children’s externalizing problems; however, its interaction with impulsivity (γ13) did, such that higher PPA predicted a more negative slope for children higher in impulsivity (Figure 2a). Range in PPA (γ14) did not predict change in child externalizing symptoms; however, its interaction with child impulsivity (γ15) did, such that smaller PPA range predicted a more negative slope for children with higher impulsivity (Figure 2b).

Figure 2. Mean PPA, PPA range, and child impulsivity predict child externalizing symptoms. Note. Mean PPA (A) and PPA range (B) both interact with child impulsivity to predict the trajectory of child externalizing symptoms. Higher PPA and lower PPA range predicted a more negative slope, particularly for children with higher impulsivity.

Parent hostility

Lower child impulsivity (γ01) predicted fewer child externalizing symptoms at age three. Mean parent hostility (γ02) predicted child externalizing symptoms at age three such that children who received lower parent hostility had fewer externalizing symptoms at age three. This was qualified by an interaction with impulsivity (γ03) such that children with lower impulsivity who received lower parent hostility had fewer externalizing symptoms at age three. Neither range in parent hostility (γ04) nor its interaction with impulsivity (γ05) predicted child externalizing symptoms at age three. Child impulsivity did not predict change in child externalizing symptoms (γ11). Neither mean hostility (γ12) nor its interaction with impulsivity (γ13) predicted change in child externalizing symptoms. Finally, range in parent hostility (γ14) predicted change in child externalizing symptoms, such that smaller hostility range predicted a more negative slope; this was qualified by a significant interaction with child impulsivity (γ15), such that smaller hostility range predicted a decrease in symptoms for children with lower impulsivity, but predicted sustained symptoms for children with higher impulsivity (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Hostility range and child impulsivity predict child externalizing symptoms. Note. Hostility range interacts with child impulsivity to predict the trajectory of child externalizing symptoms. Lower hostility range predicted a decrease in externalizing symptoms for children with lower impulsivity but predicted maintaining symptoms for children with higher impulsivity.

Parenting structure

Lower child impulsivity (γ01) predicted fewer child externalizing symptoms at age three. Mean parenting structure (γ02) predicted child externalizing symptoms at age three, such that more structure predicted fewer symptoms; this was qualified by a significant interaction with child impulsivity (γ03), such that more structure predicted fewer symptoms particularly for children with higher impulsivity. Range in parenting structure (γ04) did not predict child externalizing symptoms at age three; however, its interaction with child impulsivity (γ05) did, such that greater range in structure predicted fewer symptoms particularly for children with higher impulsivity. Child impulsivity did not predict change in child externalizing symptoms (γ11). Neither mean poor parenting structure (γ12) nor its interaction with impulsivity (γ13) predicted change in child externalizing symptoms. Finally, neither range in parenting structure (γ14) nor its interaction with impulsivity (γ15) predicted change in child externalizing symptoms.

Discussion

Parenting range, and its interactions with child temperament, may be important predictors of child outcomes (Barry et al., Reference Barry, Dunlap, Lochman and Wells2009; Lengua et al., Reference Lengua, Wolchik, Sandler and West2000), in addition to “typical” or mean parenting. While links between parenting practices and children’s externalizing psychopathology are well established (Beauchaine et al., Reference Beauchaine, Hinshaw and Pang2010; Patterson, Reference Patterson1986), few studies have examined range in parenting, and no study, to our knowledge, has examined the impact of variation in key parenting dimensions (positive affectivity, hostility, and parenting structure) on the development of externalizing symptoms throughout childhood. In addition, few studies have examined how the impact of caregiving range might differ for children who vary in impulsivity. Both mean parent positive affectivity and parent positive affectivity range predicted change in child externalizing symptoms over time, particularly for children high in impulsivity, suggesting that children high in impulsivity benefit the most from high and consistent displays of positive affectivity from their caregivers. We also observed that parent hostility range predicted child externalizing symptom development, predicting a more negative slope for children with lower impulsivity and a less negative slope for children with higher impulsivity.

Consistent with our hypotheses, the interaction between mean parent positive affectivity and child impulsivity predicted change in children’s symptoms over time. This is consistent with findings that parent positive affect (e.g., warmth and acceptance) in early childhood predicts fewer child externalizing symptoms at later timepoints (e.g., Wang et al., Reference Wang, Eisenberg, Valiente and Spinrad2016). As hypothesized, the current study adds to this literature by demonstrating that it is not only mean parent positive affectivity that interacts with child impulsivity, to impact child externalizing symptoms; range in parent positive affectivity interacted with impulsivity to predict age three symptoms and the development of symptoms throughout childhood. The literature on parent positive affectivity and externalizing symptoms is less well developed. In the current study, zero-order correlations were not observed between mean and range of positive affectivity and child externalizing symptoms; instead, it appears that associations between parent positive affectivity and child externalizing symptoms depends on child impulsivity. Consistency in parent positive affectivity may be important for demonstrating that positive behavior is rewarded, which may be particularly important for children high in impulsivity (Sagvolden et al., Reference Sagvolden, Johansen, Aase and Russell2005; Zisner & Beauchaine, Reference Zisner, Beauchaine, Beauchaine and Hinshaw2016). In addition, consistency in parent positive affectivity across situations may be important for the development of a secure caregiver–child relationship. Secure attachment to a caregiver, in turn, is associated with child sociability, compliance, and emotion regulation (Guttmann-Steinmetz & Crowell, Reference Guttmann-Steinmetz and Crowell2006). Having said that, neither mean parent positive affectivity nor its interactions with child impulsivity predicted child externalizing symptoms at age three, which was inconsistent with our hypotheses. This finding was somewhat surprising, given that previous studies have found a link between parental affect and concurrent child externalizing symptoms (e.g., Lengua et al., Reference Lengua, Wolchik, Sandler and West2000); however, many of these studies used a measure that combined both positive and negative parent affectivity into a single predictor, instead of examining them separately.

As hypothesized, we found that mean parent hostility, and its interaction with impulsivity, predicted concurrent child externalizing symptoms. This is consistent with prior literature demonstrating that parental control, including harshness and physical punishment, are associated with negative child outcomes (Kiff et al., Reference Kiff, Lengua and Zalewski2011; McLeod et al., Reference McLeod, Weisz and Wood2007). It was somewhat surprising that mean parent hostility had the strongest impact on children with low impulsivity; we hypothesized that children higher in impulsivity would be most strongly affected, since previous research has demonstrated that children with high impulsivity in particular benefit from parenting that is less harsh (Leve et al., Reference Leve, Kim and Pears2005; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Farver and Zhang2009). However, these studies (i.e., Ahmad & Hinshaw, Reference Ahmad and Hinshaw2018; Leve et al., Reference Leve, Kim and Pears2005; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Farver and Zhang2009) were of older children, so it is possible that the relationship between child impulsivity, caregiving, and symptoms (Patterson, Reference Patterson1986) differ in early childhood. Additionally, these studies did not account for hostility range, so it is possible that parent hostility has the greatest impact on children with lower impulsivity when it is not confounded by the effect of hostility range. Finally, there were few displays of high parent hostility in the current study; since impulsivity is associated with punishment insensitivity (Nichols et al., Reference Nichols, Briggs-Gowan, Estabrook, Burns, Kestler, Berman, Henry and Wakschlag2015), it is possible that less impulsive children were responding adaptively to these normative degrees of parent hostility, whereas impulsive children were relatively impervious to milder displays of hostility.

This study also added to the literature by demonstrating that hostility range interacts with impulsivity to predict change in child externalizing symptoms over time, although the findings were contrary to our hypotheses; specifically, high hostility range was associated with a decrease in symptoms for children with higher impulsivity and mean hostility, hostility range, and their interactions with impulsivity did not predict concurrent child symptoms. Additionally, neither mean parent hostility nor its interaction with impulsivity predicted change in externalizing symptoms throughout middle childhood. Again, because there were relatively few displays of parent hostility in our community-dwelling sample, it is possible that variation in this dimension reflected relatively minor changes in parent responses based on child behavior, thereby providing necessary negative feedback to children higher in impulsivity (Sagvolden et al., Reference Sagvolden, Johansen, Aase and Russell2005).

We found that mean parenting structure was associated with fewer child externalizing symptoms at age three, particularly for children higher in impulsivity. This was consistent with the many findings that show that children, particularly those high in impulsivity, benefit from consistency in discipline (e.g., Barry et al., Reference Barry, Dunlap, Lochman and Wells2009; Lengua et al., Reference Lengua, Wolchik, Sandler and West2000); however, contrary to our hypotheses, we also found that greater range in structure was associated with fewer child externalizing symptoms, particularly for children higher in impulsivity. This is surprising given prior findings on parental discipline. For example, Patterson’s coercion model (e.g., Patterson, Reference Patterson1986) explains poor discipline as an escalation of harsh and aggressive behavior, followed by withdrawal of discipline, which would seem more consistent with the notion that greater range of structure is problematic for high-risk children. It is possible that the behaviors observed in the tasks did not fully encompass differences in the rules parents set for their children at home and did not allow us to observe maladaptive aspects of variable parenting structure in this study. Contrary to our hypotheses, mean parenting structure was unrelated to the development of child externalizing symptoms over time. As discussed in Halgunseth et al. (Reference Halgunseth, Perkins, Lippold and Nix2013), many studies linking inconsistent discipline to child externalizing psychopathology have used measures that conflate harsh or hostile parenting and poor parenting structure (Brody et al., Reference Brody, Murry, Ge, Kim, Simons, Gibbons, Gerrard and Conger2003; Edens et al., Reference Edens, Skopp and Cahill2008); therefore, it is possible that any longitudinal effects were due to parent hostility rather than structure. Overall, parenting structure did not appear to influence child symptom development as much as parent positive affectivity and hostility, regardless of child impulsivity.

Findings of this study contribute to the large literature establishing linkages between aggregate caregiving and child outcomes by demonstrating that parenting range, at least in terms of parent positive affectivity and hostility, is a unique predictor of child externalizing symptoms. While most previous studies on parenting variability and child development have focused on discipline (e.g., Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, McBurnett and Pfiffner2011), our findings also show the importance of range in positive dimensions of parenting in addition to consistency in harmful parenting practices. In addition, our findings indicate that certain dimensions (i.e., parenting structure) may have a greater impact on concurrent child externalizing symptoms, while others (i.e., parent positive affectivity) may primarily impact symptom development over time. These findings likely have important implications for determining targets of treatment in parent-focused interventions.

Although the current study focused on the child’s primary caregiver, there is some evidence that the impact of parenting variability also differs depending on whether it is displayed by mothers or fathers (Gryczkowski et al., Reference Gryczkowski, Jordan and Mercer2010; Lunkenheimer et al., Reference Lunkenheimer, Olson, Hollenstein, Sameroff and Winter2011). Therefore, it may be useful to examine different dimensions when assessing variability in fathers, such as paternal involvement and poor monitoring. Furthermore, while some studies have shown that inconsistent discipline is related to externalizing behavior in adolescents (Edens et al., Reference Edens, Skopp and Cahill2008; Halgunseth et al., Reference Halgunseth, Perkins, Lippold and Nix2013), it may prove useful for future studies to examine a broader range of parenting variables to determine whether parenting variability is important in predicting adolescent externalizing behavior. Finally, parenting is also associated with children’s internalizing psychopathology (Burstein et al., Reference Burstein, Stanger, Kamon and Dumenci2006; Caron et al., Reference Caron, Weiss, Harris and Catron2006; Kuckertz et al., Reference Kuckertz, Mitchell and Wiggins2018; Suor et al., Reference Suor, Calentino, Granros and Burkhouse2021). Therefore, parents’ range in these behaviors should be examined as unique predictors of child internalizing symptoms as well.

Strengths and weaknesses

This study had several strengths, most notably its longitudinal design with good retention across four waves of data collection. Most previous studies examining parenting have used concurrent measures or one follow-up timepoint (e.g., Lengua et al., Reference Lengua, Wolchik, Sandler and West2000; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Eisenberg, Valiente and Spinrad2016); however, the four waves of data collection allowed for a more precise measure of children’s development of child externalizing psychopathology. In particular, by using a multilevel model that included random intercepts and slopes, we were able to examine the impact of parenting on both concurrent child externalizing symptoms and their change throughout childhood. We also used three different parent-child interaction tasks to capture caregiving range across time and context, a likely contributor to children’s development about which relatively little is known. The use of a latent difference score to model caregiver range yielded a more reliable, objective index of caregiving (King et al., Reference King, King, McArdle, Saxe, Doron-LaMarca and Orazem2006). We also used observational measures of child impulsivity to provide a more objective assessment of child behavior that was not confounded by factors that may bias parent-report measures, such as parent mood state or history of psychopathology (Olino & Hayden, Reference Olino, Hayden, Butcher and Kendall2018). However, the study had some important limitations; in particular, we assessed caregiving and child impulsivity at a single time point, despite the fact that parents and children influence one another through reciprocal interactions that unfold early in, and across, child development (e.g., Kiff et al., Reference Kiff, Lengua and Zalewski2011; Lengua & Kovacs, Reference Lengua and Kovacs2005; Lippold et al., Reference Lippold, Fosco, Hussong and Ram2019; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Kryski, Smith, Joanisse and Hayden2020). Lengua and Kovacs (Reference Lengua and Kovacs2005) observed bidirectional effects in a longitudinal study of child temperament and parenting. In particular, they found that child irritability predicted parents’ inconsistent discipline and vice versa. Lippold et al. (Reference Lippold, Fosco, Hussong and Ram2019) also found that greater youth maladjustment (i.e., delinquency, substance use, internalizing problems) predicted greater lability in parents’ warmth, for parents high in internalizing problems; for parents low in internalizing problems, maladjustment predicted lower lability in warmth. It is almost certain that such interactions between children and their caregivers prior to age three evolved to contribute to the current pattern of findings. Future research may shed light on even earlier patterns of parent–child interactions that ‘set the stage’ for children’s externalizing psychopathology in the context of early impulsivity. Another limitation to the study was the limited range for both parent hostility and poor structure; although the vast majority of parents showed some variability in relevant parenting behaviors (N = 346 showed variation on either parent hostility or poor structure). It will be beneficial for future studies to examine similar models in clinically referred samples, or to select for extreme variation in parenting practices, to better understand how these variables impact child externalizing symptoms. Additionally, we examined the child’s primary caregiver, usually the mother, only, despite the importance of caregiving received from others, including fathers (Gryczkowski et al., Reference Gryczkowski, Jordan and Mercer2010; Lunkenheimer et al., Reference Lunkenheimer, Olson, Hollenstein, Sameroff and Winter2011). While we conceptualized caregiving as an environmental variable in the current study, as have others (e.g., Bakermans-Kranenburg & Van Ijzendoorn, Reference Bakermans-Kranenburg and Van Ijzendoorn2006; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Sessa, Avenevoli and Essex2002; Wiggins et al., Reference Wiggins, Mitchell, Hyde and Monk2015; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Farver and Zhang2009), parents’ own individual differences contribute to their caregiving, including parent impulsivity and self-control (e.g., Latzman et al., Reference Latzman, Elkovitch and Clark2009; Verhoeven et al., Reference Verhoeven, Junger, Van Aken, Deković and Van Aken2007); thus, a more complete model of relationships between caregiving and individual difference factors in families would need to account for person/parent-environment correlations.

In conclusion, caregiver consistency, in addition to “typical” caregiving, appears to contribute to children’s externalizing psychopathology, at least in the context of caregiver positive affectivity range and hostility range. These findings yield further support for parenting interventions that enhance positive parenting (e.g., Hinshaw et al., Reference Hinshaw, Owens, Wells, Kraemer, Abikoff, Arnold, Conners, Elliott, Greenhill, Hechtman, Hoza, Jensen, March, Newcorn, Pelham, Swanson, Vitiello and Wigal2000) and reduce displays of hostility, especially early in child development, given that these aspects of caregiving may have particularly longstanding implications for children’s externalizing psychopathology.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579423000482

Funding statement

We would like to thank the Canadian Institute of Health Research, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (Canadian Graduate Scholarship, Master’s), and the Ontario Graduate Scholarship for funding this research.

Conflicts of interest

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Appendix A

Table A1. Number of minimum and maximum ratings from each task

Note. PPA = parent positive affectivity.