No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

1 The authors thank the anonymous referee for many helpful suggestions. We also thank Francois Avril, Salle des Manuscrits, Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris; Dom Faustino Avagliano, priore and archivista of Monte Cassino; and the Istituto di Patologia del Libra, Rome, for providing access to the manuscripts; and John Younger for providing photographs.

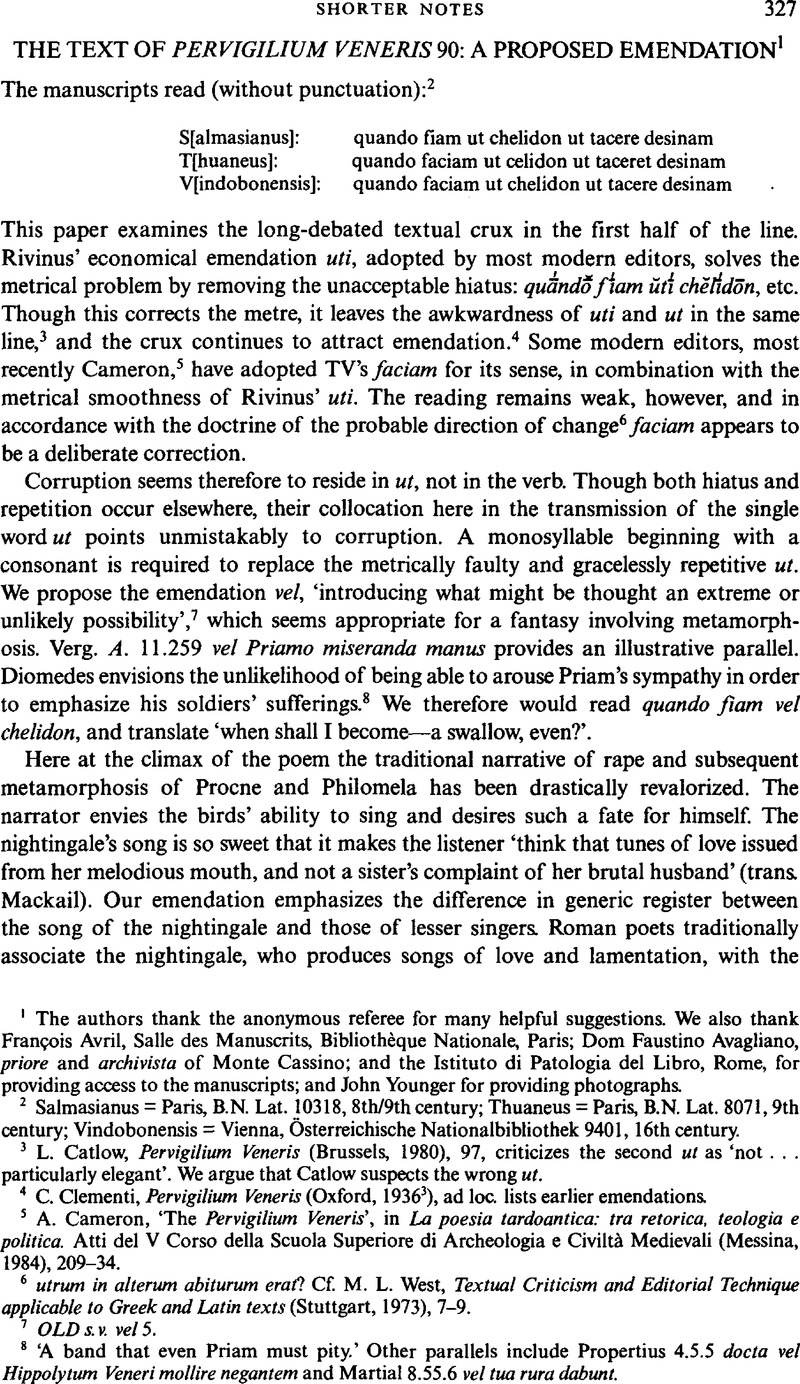

2 Salmasianus = Paris, B.N. Lat. 10318, 8th/9th century; Thuaneus = Paris, B.N. Lat. 8071,9th century; Vindobonensis = Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek 9401,16th century.

3 Catlow, L., Pervigilium Veneris (Brussels, 1980), 97Google Scholar, criticizes the second ut as ‘not… particularly elegant’. We argue that Catlow suspects the wrong ut.

4 Dementi, C., Pervigilium Veneris (Oxford, 1936)Google Scholar, ad loc. lists earlier emendations.

5 Cameron, A., ‘The Pervigilium Veneris’, in La poesia tardoantica: tra retorica, teologia epolitico. Atti del V Corso della Scuola Superiore di Archeologia e Civiltá Medievali (Messina, 1984), 209–34.Google Scholar

6 utrum in alterum abiturum eraf? Cf. West, M. L., Textual Criticism and Editorial Technique applicable to Greek and Latin texts (Stuttgart, 1973), 7–9.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

7 OLDs.v. ve15.

8 ‘A band that even Priam must pity.’ Other parallels include Propertius 4.5.5 docta vel Hippolytum Veneri mollire negantem and Martial 8.55.6 vel tua rura dabunt.

9 Cf. G. Rosati, CQ 46 (1996), 214–15; A. Sauvage, Ètude de thèmes animaliers dans la poèsie latine (Brussels, 1975), part II, ch. 4.; A. Steier, RE 13.1864.42ff.

10 Compare the opposition of swan and bee at Hor. C. 4.2.25–32, which ‘epitomizes the disavowal of the grandiloquent style’ cf. Davis, G., Polyhymnia: The Rhetoric of Horatian Lyric Discourse (Berkeley, 1991), 133ff.Google Scholar

11 OLD s.v. vel 4b. Cf. Sihler, A. L., New Comparative Grammar of Greek and Latin (Oxford, 1995), 230–1Google Scholar, 539–41.

12 Parallels include, among many others, Plaut. Mil. 25 edepol vel elephanto in India.

13 Cf. Lindsay, W. M., Notae Latinae (Cambridge, 1915), δ 396.Google Scholar

14 We add the instance below from the Passio Perpetuae et Felicitatis to the examples cited by Havet, L., Manuel de critique verbale appliquee aux textes latins (Rome, 1911), δ 772.Google Scholar

15 CLA 5, no. 593. Examples include page 67, line 19 (the last three letters of hostis) and page 180, line 18 (the final letters -rientem in carientem).

16 Spallone, M., IMU 25 (1982), 49–51.Google Scholar

17 C. I. M. I. Van, Beek (ed.), Passio Sanctarum Perpetuae et Felicitatis 1 (Nijmegen, 1936), 4 and 6.Google Scholar

18 Cf. Fridh, A., Le probléme de la Passion des Saintes Perptue et Fèlicitè (Göteborg, 1968).Google Scholar We have benefited from the discussion of N. Bernstein, S. Findley, M. Drinkwater Ottone, K. Peterson, and G. Renberg, ‘Southern Italy and the transmission of the Passio Perpetuae: a study of the unique manuscript Monte Cassino 204’ (forthcoming).

19 Clementi (n. 3), 262.

20 In a forthcoming companion study, ‘The reception of Pervigilium Veneris in T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land’, we examine the effects of this textual corruption on the modern reception of the poem.