No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

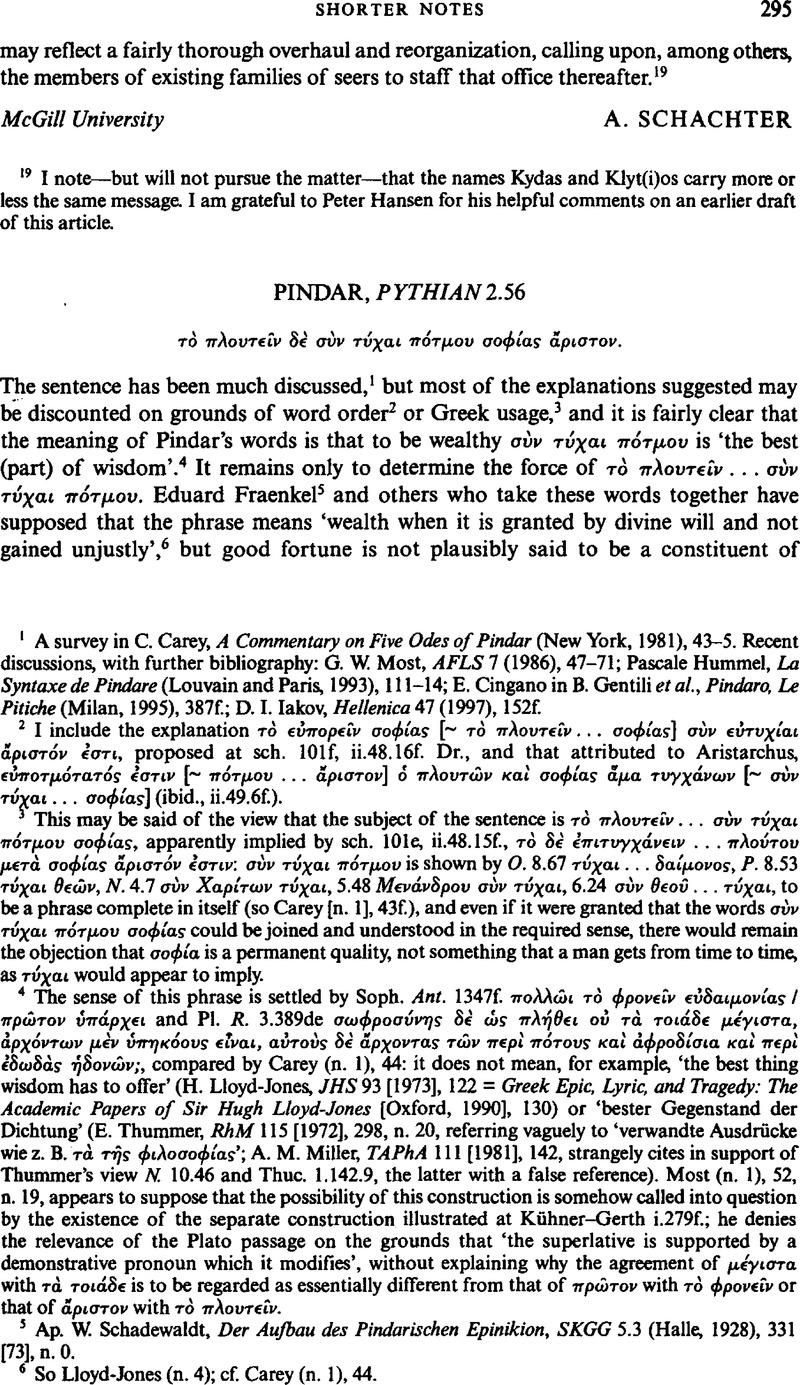

1 A Survey in Carey, C., A Commentary on Five Odes of Pindar (New York, 1981), 43–5.Google Scholar Recent discussions, with further bibliography: Most, G. W., AFLS 7 (1986), 47–71Google Scholar; Hummel, Pascale, La Syntaxe de Pindare (Louvain and Paris, 1993), 111–14Google Scholar; Cingano, E. in Gentili, B.et al., Pindaro, Le Pitiche (Milan, 1995), 387f.Google Scholar; Iakov, D. I., Hellenica 47 (1997), 152f.Google Scholar

2 I include the explanation τò εὐπoρεῖν σoφας [~ πò πλoντεῖν … σoφâς] σὺν εςτςχι ἄρστóν στι, proposed at sch. lOlf, ii.48.16f. Dr., and that attributed to Aristarchus, εὐπoτμóτατóς [πóτμoν hellip; ἄριστoν] πλoντν κα σoφας ᾰμα τυγχνων [~ σὺντὺχαι … σoπας] (ibid., ii.49.6f.).

3 This may be said of the view that the subject of the sentence is τò πλoυτεῖν … σὺν τχαι πóτyᾰ σoφας, apparently implied by sch. 101e, ii.48.15f., τò δ πιτυγχνειν … πλoτoυ μετᾰ σoφσς ᾰριστóν στιν: σὺν τχαι πóτμoυ is shown by O. 8.67 τχαι … δαμoνoς, P. 8.53 τχαι θεν, N. 4.7 αὺν χαρτων τχαι, 5.48 Mεννδρoν αν τχαι, 6.24 αὺν θεoυ … τχαι, to be a phrase complete in itself (so Carey [n. 1], 43f.), and even if it were granted that the words αν τχαι πóτμoυ σoφας could be joined and understood in the required sense, there would remain the objection that σoφα is a permanent quality, not something that a man gets from time to time, as τχαι would appear to imply.

4 The sense of this phrase is settled by Soph. Ant. 1347f. πoλλι τò φρoτεῖν εὐδαιμoνας / πρτoν ὑπρχει and P1. R. 3.389de σωφρoσνησ δ ὡς πλθει oὺ τᾰ τoιδε μγιστα ρχóντων μν ὑπηκóoυς εἰναι, αrsquo;τoὺς δ ἄρχoντας τν περ πóτoυς κα φρoδσια κα περ δωδς δoνν;, compared by Carey (n. 1), 44: it does not mean, for example, ‘the best thing wisdom has to offer’ (Lloyd-Jones, H., JHS 93 [1973]Google Scholar, 122 = Greek Epic, Lyric, and Tragedy: The Academic Papers of Sir Hugh Lloyd-Jones [Oxford, 1990], 130) or ‘bester Gegenstand der Dichtung’ (Thummer, E., RhM 115 [1972], 298Google Scholar, n. 20, referring vaguely to ‘verwandte Ausdrücke wie z. B. τᾰ τς φιλoσoφας’;; Miller, A. M., TAPhA 111 [1981], 142Google Scholar, strangely cites in support of Thummer's view N. 10.46 and Thuc. 1.142.9, the latter with a false reference). Most (n. 1), 52, n. 19, appears to suppose that the possibility of this construction is somehow called into question by the existence of the separate construction illustrated at Kūhner-Gerth i.279f.; he denies the relevance of the Plato passage on the grounds that ‘the superlative is supported by a demonstrative pronoun which it modifies’, without explaining why the agreement of μγιστα with τᾰ τoιδε is to be regarded as essentially different from that of πρτoν with τò φρoνεν or that of ἄριστoν with τò πλoντεν.

5 Ap. Schadewaldt, W., Der Aufbau des Pindarischen Epinikion, SKGG 5.3 (Halle, 1928), 331Google Scholar [73], n. 0.

6 So Lloyd-Jones (n. 4); cf. Carey (n. 1), 44.

7 Cf. Péron, J., REG 87 (1974), 8.Google Scholar

8 For the use of the first person, cf., in the parallel passage in P. 3, lines 107–11: σμικρòς ν σμικρoς, μγας ν μεγλoις / σσoμαι, τòν δ’ μφπoντ’ αἰε φρασν / δαμoν’ σκσω κατ’ μᾰν θεραπεων μαχανν. / εἰ δ μoι πλoυτoν θεòς βρòν ρξαι, / λπδ’ ἔχω κλoς εὑρσθαι κεν ὐψηλòν πρòσω.