1. Introduction

Korean subject honorification has a property that leads some feature of an argument to be reflected morphologically on the verb.Footnote 1 Although there is an apparent optionality issue, Korean subject honorification may be treated as an agreement phenomenon, comparable to English subject-verb agreement (Choe Reference Choe1988, Kang Reference Kang1988, Ryu Reference Ryu1993, Choi Reference Choi2010, a.o.).Footnote 2 In this vein, the present study investigates the nature of Korean coordinate subjects participating in agreement with an honorific verb and its implication for Chomsky's (Reference Chomsky, Martin, Michaels and Uriageraka2000, Reference Chomsky and Kenstowicz2001) theory of Agree (feature valuation at a distance) and for Closest Conjunct Agreement (CCA).Footnote 3

Choe (Reference Choe2004) and Choi (Reference Choi2010) claim that the grammaticality of (1a) and (1b) – in which the subject is a conjoined NP and the value of [Hon] differs between conjunct – cannot be explained by a syntactic agreement approach, since the first conjunct in (1a) and (1b) is specified with [+Hon], and the second is specified with [−Hon].

(1)

a. [[+Hon] & [−Hon]] [+Hon]

Sensayng-nim-kwa etten ai-ka hamkkey o-si-esse.

teacher-hon-and some child-nom together come-hon-past

‘A teacherHon and a child cameHon together.’

b. [[+Hon] & [−Hon]] [−Hon]

Sensayng-nim-kwa etten ai-ka hamkkey o-asse.

teacher-hon-and some child-nom together come-past

‘A teacherHon and a child came together.’

c. [[−Hon] & [+Hon]] [+Hon]

Etten ai-wa sensayng-nim-i hamkkey o-si-esse.

some child-and teacher--hon-nom together come-hon-past

‘A child and a teacherHon cameHon together.’ (modified from Choi Reference Choi2010: (8))

Specifically, Choi (Reference Choi2010) claims that the similar acceptability of (1a) and (1b) is problematic for the syntactic agreement approach,Footnote 4 in that the honourability of the verbs in (1a) and (1b) does not match the honourability of one of the coordinate subjects. In addition, Choe (Reference Choe2004) notes that in (1a), an honorific noun sensayng-nim ‘teacherHon’ and a non-honorific noun ai ‘child’ are conjoined to form a subject, and change in the order of the two as in (1c) does not appear to affect the appropriateness of the sentence in any significant way.

Since honorification is potentially indicative of the availability of syntactic agreement effects and linguistic theories are ideally built on robust empirical foundations, this question merits rigorous verification. We set out to provide experimental evidence of a significant acceptability difference between (1a) and (1b), as well as between (1a) and (1c). We then discuss whether honorifically-mixed coordination of subjects in Korean is relevant to the computation of closest conjunct agreement.

We argue that the honorific agreement of coordinate subjects with verbal si in Korean is both hierarchically and linearly conditioned. The core of our theoretical account relies on the premise that conjoined phrases (&P) compute their own singular/plural number, but not their own honourability in Korean. As agreement is designed to provide φ-feature values on predicates, either of the coordinate subjects may be chosen as a source of honorific features.

This article is organized as follows. Section 2 sketches the theoretical background of CCA and subject honorification. We discuss two types of previous approaches to conjunct agreement: a purely syntactic approach (e.g., Bošković Reference Bošković2009) and a partly postsyntactic approach (e.g., Marušič et al. Reference Marušič, Nevins and Badecker2015). Section 3 presents an acceptability experiment. In section 4, we develop a partly syntactic and partly postsyntactic approach that addresses Korean honorification with coordinate subjects. Importantly, this approach derives the attested preverbal Last Conjunct Agreement (LCA) pattern, while ruling out the unattested preverbal First Conjunct Agreement (FCA) pattern. Furthermore, it does so with explicit reference to linear order, suggesting that agreement is not confined to syntax proper. Section 5 concludes the article.

2. Background

Languages differ as to which conjunct of coordinate phrases verbal morphemes agree with in number and gender. CCA refers to agreement with the first conjunct when the subject is postverbal (i.e., V–[S1 & S2]), and agreement with the last conjunct when the subject is preverbal (i.e., [S1 & S2]–V). Highest Conjunct Agreement (HCA) refers to agreement with the first conjunct, regardless of the relative placement of the conjunct with respect to the verb. The existence of so-called CCA raises a technical challenge for the theory of Agree (Chomsky Reference Chomsky, Martin, Michaels and Uriageraka2000, Reference Chomsky and Kenstowicz2001), because agreement seems to be sensitive to linear proximity to the goal, rather than to hierarchy. To account for this fact, recent approaches spell out the concept of Agree to settle the issue of minimality (Bošković Reference Bošković2009, Murphy and Puškar Reference Murphy and Puškar2018) or to procrastinate some part of the agreement process to the postsyntactic component (Bhatt and Walkow Reference Bhatt and Walkow2013, Marušič et al. Reference Marušič, Nevins and Badecker2015).

2.1 Closest conjunct agreement (CCA)

It is well-known that some Slavic languages show the closest conjunct (i.e., first or last conjunct) agreement patterns for coordinate subjects (Bošković Reference Bošković2009, Marušič et al. Reference Marušič, Nevins and Badecker2015, Murphy and Puškar Reference Murphy and Puškar2018). FCA is the pattern of CCA in which the verb agrees with the first conjunct of a postverbal conjunct phrase, as in (2).

Serbo-Croatian

(2) Juče su uništena [sva sela i sve varošice].

yesterday are destroyed.PL.N all villages.N and all towns.F

‘All villages and all towns were destroyed yesterday.’ (Bošković Reference Bošković2009: (1a))

In case of LCA, the verb agrees with the second/last conjunct in a preverbal subject, as shown in (3).

Serbo-Croatian

(3) [Sva sela i sve varošice] su (juče) uništene.

all villages.N and all towns.F are yesterday destroyed.PL.F

‘All villages and all towns were destroyed yesterday.’ (Bošković Reference Bošković2009: (1b))

Korean coordinate subjects are preverbal whether they are vP/VP-internal or not, since Korean is head-final and specifier-initial. Choosing the closest goal based on a hierarchical structure will result in agreement with the first conjunct, (i.e., FCA (or HCA)), as in (4a). On the other hand, if the structure has been linearized before Agree takes place, then closeness is defined by linearity and the second conjunct will be chosen, yielding LCA, as in (4b).

(4)

a. Ape-nim-kwa John-i cwungkwuke-lul paywu-si-essta.

father-hon-and John-nom Chinese-acc learn-hon-past

‘FatherHon and John learnedHon Chinese.’(acceptable under LCA)

b. John-kwa ape-nim-i cwungkwuke-lul paywu-si-essta.

John-and father-hon-nom Chinese-acc learn-hon-past

‘John and fatherHon learnedHon Chinese.’ (acceptable under LCA)

If both the preverbal FCA (or HCA) and LCA strategies were available in Korean, the two examples in (4) would be acceptable. Therefore, a successful theory of CCA in Korean has to explain which of the conjuncts in coordination is targeted by honorific agreement.

For the FCA pattern, Bošković (Reference Bošković2009) argues that the participle as a probe agrees with conjoined phrases (&P) only in number because &P is φ-deficient and that it simultaneously agrees with the equally accessible gender feature of the first conjunct. As a result, FCA surfaces in a postverbal position. Note that there is no movement involved in FCA. Meanwhile, if the participle as a probe induces movement of the subject into a preverbal position, it finds both &P and the first conjunct as a goal. This is because the first conjunct can be dislocated out of &P in violation of the Coordinate Structure Constraint in Serbo-Croatian. Due to this lethal ambiguity within the first cycle of Agree, neither &P nor the first conjunct can function as the goal and therefore cannot be pied-piped into a higher preverbal position. The participle probe then activates the second cycle of Agree, and finds the lower (i.e., the second) conjunct. No ambiguity arises this time, since non-initial conjuncts cannot be dislocated out of &P in Serbo-Croatian. The probe can pied-pipe the coordinate subject and agree with the second conjunct of the subject. In short, the distinction between FCA and LCA in Serbo-Croatian, in Bošković's analysis, is crucially related to movement; his analysis explains special properties of Serbo-Croatian where only the first conjunct can violate the Coordinate Structure Constraint, and movement is linked with LCA, without reference to linearity.Footnote 5

Marušič et al. (Reference Marušič, Nevins and Badecker2015) also assume that &P is φ-deficient. A probe can value its number features, but not its gender features, from a goal &P. Therefore, the agreement process can be passed over to the postsyntactic component. Marušič et al. report that three possibilities exist in Slovenian when the conjunction is preverbal, as illustrated in (5):

Slovenian

(5) [Krave in teleta] so odšla/odšle/odšli na pašo.

cow.PL.F and calf.PL.N aux.PL went.PL.N/PL.F/PL.M on graze

‘Calves and cows went grazing.’ (Marušič et al. Reference Marušič, Nevins and Badecker2015: (20))

When the participle tries to agree in gender with the conjunction, it selects one of the conjuncts to agree with (i.e., FCA or LCA), or inserts a default gender value (masculine) (i.e., Resolved Agreement).Footnote 6

Similar to Bošković's (Reference Bošković2009) and Marušič et al.'s (Reference Marušič, Nevins and Badecker2015) proposals, we assume that the conjunction (&) in Korean computes a value for number based on the values of its respective conjuncts. Number then always agrees with the conjunction (&):

(6)

a. John-kwa Mary-ka talye-tul wassta.

John-and Mary-nom run-pl came

‘John and Mary came running.’

b. *John-i talye-tul wassta.

John-nom run-pl came

Intended: ‘John came running.’

On the other hand, we assume that the conjunction is unable to calculate its own honorific value in (4). As a result, when verbal si tries to agree honorifically with the conjunction, there is only one option: it does not select the conjunction, but rather one of the conjuncts, to agree with.

2.2 Korean subject honorification

Korean subject honorification is largely determined by two factors. One is syntactic. The other is pragmatic (the element associated with honorification must be socially superior to and respected by the speaker). As a consequence, there have been at least two competing strands of analysis of honorification in the Korean (and Japanese) literature: syntactic agreement analyses vs. pragmatic agreement analyses.

Under the Minimalist Program of Chomsky (Reference Chomsky1995), syntactic agreement analyses employ feature checking (see Toribio Reference Toribio and Halpern1990, Ura Reference Ura2000, Choi Reference Choi2010, a.o.). For example, Ura (Reference Ura2000) and Choi (Reference Choi2010) argue that honorification is an instance of feature checking between Agr(eement) and subject. Under Chomsky (Reference Chomsky, Martin, Michaels and Uriageraka2000, Reference Chomsky and Kenstowicz2001), honorification is explained via Agree (Boeckx and Niinuma Reference Boeckx and Niinuma2004; Boeckx Reference Boeckx2006; Ivana and Sakai Reference Ivana and Sakai2007; Kishimoto Reference Kishimoto2010, Reference Kishimoto2012). For example, Kishimoto (Reference Kishimoto2010, Reference Kishimoto2012) proposes that Japanese subject honorification is vP-level agreement in the sense that an honorific head agrees with an argument marked with [Hon] in Spec of vP.

On the other hand, there have been pragmatic agreement accounts of honorification (see Pollard and Sag Reference Pollard and Sag1994, Arka Reference Arka2005, Ide Reference Ide, Lakoff and Ide2005, Kim and Sells Reference Kim and Sells2007, a.o.). Under this view, pragmatic agreement is determined by the social rules of a society where the language is used as a way of showing a sense of self and relation to others.

In the paradigm in (7a–d), Choe (Reference Choe2004) and Choi (Reference Choi2010) point out that (7c) could pose a problem for the syntactic agreement approach.

(7)

a. John-i Seoul-eyse thayena-essta.

John-nom Seoul-in be.born-past

‘John was born in Seoul.’

b. Eme-nim-i Seoul-eyse thayena-si-essta.

mother-hon-nom Seoul-in be.born-hon-past

‘MotherHon was bornHon in Seoul.’

c. Eme-nim-i Seoul-eyse thayena-essta.

mother-hon-nom Seoul-in be.born-past

‘MotherHon was born in Seoul.’

d. ?*John-i Seoul-eyse thayena-si-essta.

John-nom Seoul-in be.born-hon-past

‘John was bornHon in Seoul.’

Choi (Reference Choi2010) reports that (7c) is acceptable to most Korean speakers, which he claims is unexpected under the syntactic agreement approach, as there is a mismatch between the [+Hon] subject with nim and the [−Hon] verbal without si.

Given the acceptability of (7c), we question the common assumption that [Hon] is a binary feature as [±Hon] (Choi Reference Choi2010). We propose that if honorification is syntactic, the relevant feature should be privative, without being marked with [±] values. More precisely, we adopt Kim and Sells's (Reference Kim and Sells2007) claims about Korean subject honorification:

(8)

a. Honorification has a privative property.

b. Nominal honorification differs from verbal honorification.

In keeping with the spirit of (8a), we propose that there exists an unspecified honorific feature [Hon] within the minimalist program. Also, we interpret (8b) as indicating that the functional element in Agr, the honorific verbal si, bears an uninterpretable [uHon] feature, whereas the honorific nominal bears an interpretable [iHon] feature.

In Chomsky (Reference Chomsky, Martin, Michaels and Uriageraka2000, Reference Chomsky and Kenstowicz2001), Agree constrains the content of φ-features on the probe, not on the goal (argument NPs), since Agree is a valuation operation, and goals come out of the lexicon with fully-valued φ-sets. Under the assumption that the Subject Agreement Phrase (AgrP) comprising its agreement head (Agr) is projected above vP, and that Agr acts as a probe that seeks a matching goal under c-command, we propose that if the uninterpretable formal feature [uHon] on Agr is valued and deleted as a consequence of agreement with the interpretable formal feature [iHon] on a goal NP, the derivation of subject honorification converges as in (9); if not, the derivation crashes.

(9) [AgrP [vP NP[i Hon] [VP … V] v] Agr[u Hon]]

We postulate that AgrP represents an agreement projection optionally realized in clause structure, and that it gives rise to a complex predicate where the honorific verbal si is attached to its associated verb morphologically.

Given the above theoretical devices, we propose that the examples in (7a–d) are derived as in (10a–d):

(10)

a. normal referent normal verb

b. honorific referent[iHon] honorific verb[u Hon]

Agree is successful!

c. honorific referent[iHon] normal verb

d. normal referent honorific verb[uHon]

Agree fails!

For (10a), there is no agreement process with respect to honorification. For (10b), we propose that [uHon] of the honorific verbal si probes down an honorific referent with [iHon] and gets valued via Agree. In (10c), we propose that [iHon] of an honorific nominal is interpretable at LF, thus not being involved in feature valuation. That is, no agreement process with respect to honorification is triggered. For (10d), we propose that the derivation crashes because [uHon] of the honorific verbal si does not find an honorific referent marked with [iHon].

Choi and Harley (Reference Choi and Harley2019) argue that Korean honorific morphemes are inserted via morphosyntactic rules: Agr nodes are sprouted and subsequently realized as agreement markers. The rules are syntax-dependent but not part of the syntactic computation. According to them, any argument marked with the honorific nominative kkeyse must accompany the honorific verbal si. Their argument is based on the following example:

(11) Sensayngnim-kkeyse haksayngtul-ul po-*(si)-essta.

teacher-hon.nom students-acc see-*(hon)-past

‘The teacher saw the students.’ (Choi and Harley Reference Choi and Harley2019: (20b))

They judge the si-less example in (11) as ungrammatical, and claim that an honorific nominative argument always triggers honorification. However, as attested by Song et al.'s (Reference Song, Choe and Oh2019) experimental work, the si-less example in (11) is acceptable to most Korean speakers. Contra Choi and Harley, we observe that the presence of an honorific nominative argument does not warrant verbal honorification. We thus argue that Korean subject honorification is a reflex of verbal si agreement with an honorific argument, not as a result of nominal (kkeyse or nim) agreement with verbal si.

With this background in mind, we launch an empirical investigation of whether the order of an honorific referent within coordinate subjects affects the acceptability of Korean honorification, thus showing the CCA effect.

3. Experiment

In head-final languages such as Korean, an agreeing verb is located to the right of coordinate subjects. If there is agreement only with the linearly closest coordinate subject, agreement will happen with the last subject. Given this, we set out to test the following predictions:

(12)

a. When the last conjunct of coordinate subjects is incongruous with an honorific verb, acceptability will decrease, but when it is incongruous with a normal verb, no such decrease in acceptability will occur.

b. Honorific agreement of subject is triggered only when verbal si appears, whose existence may decrease acceptability due to its markedness (e.g., its morphology, lower frequency, or processing burden).Footnote 7

3.1 Design and materials

The predictions in (12) led us to construct an experiment with a 2 × 2 design, crossing the honourability of the PREDICATE (NorV (normal, non-honorific verb) vs. HonV (honorific verb)) and the CONGRUENCE of honourability between the verb and the honorifically mixed coordinate subject (Local.Match (an honorifically-congruent NP in the last conjunct) vs. Local.Mismatch), as sampled in (13).

(13)

a. [NorV | Local.Match]

Ape-nim-kwa John-i cwungkwuke-lul paywu-essta.

father-hon-and John-nom Chinese-acc learn-past

‘FatherHon and John learned Chinese.’ (see (1b))

b. [NorV | Local.Mismatch]

John-kwa ape-nim-i cwungkwuke-lul paywu-essta.

John-and father-hon-nom Chinese-acc learn-past

‘John and fatherHon learned Chinese.’

c. [HonV | Local.Match]

John-kwa ape-nim-i cwungkwuke-lul paywu-si-essta.

John-and father-hon-nom Chinese-acc learn-hon-past

‘John and fatherHon learnedHon Chinese.’ (see (1c))

d. [HonV | Local.Mismatch]

Ape-nim-kwa John-i cwungkwuke-lul paywu-si-essta.

father-hon-and John-nom Chinese-acc learn-hon-past

‘FatherHon and John learnedHon Chinese.’ (see (1a))

The [NorV] conditions had a normal verb, and the normal (i.e., non-honorific) NP was the last conjunct of the coordinate subject in the [NorV | Local.Match] condition and the first conjunct in the [NorV | Local.Mismatch] condition. The [HonV] conditions had an honorific verb (marked with verbal si), and the honorific NP (marked with nominal nim) was the last conjunct of the coordinate subject in the [HonV | Local.Match] condition and the first conjunct in the [HonV | Local.Mismatch] condition. The full list of experimental items is available online.Footnote 8

According to our prediction in (12), the [NorV] conditions will be rated as more acceptable than the [HonV] conditions. More importantly, the [HonV] conditions, but not the [NorV] conditions, will show the penalty of honorific incongruence between the verb and the last conjunct NP of coordinate subjects. This prediction will be attested by a greater difference in acceptability between the [HonV] conditions than that between the [NorV] conditions, which can be evident statistically by a significant 2 × 2 interaction between the two factors (PREDICATE × CONGRUENCE) within these four conditions.

In addition to the four conditions with partial honorific mismatches in (13), we added the following four conditions with full honorific (mis)matches as the baseline conditions:

(14)

a/d. [NorV | Full.Match]/[HonV | Full.Mismatch]

John-kwa Mary-ka cwungkwuke-lul paywu-essta/paywu-si-essta.

John-and Mary-nom Chinese-acc learn-past /learn-hon-past

‘John and Mary learned/learnedHon Chinese.’

b/c. [NorV | Full.Mismatch]/[HonV | Full.Match]

Ape-nim-kwa eme-nim-i cwungkwuke-lul

father-hon-and mother-hon-nom Chinese-acc

paywu-essta/paywu-si-essta.

learn-past/learn-hon-past

‘FatherHon and motherHon learned/learnedHon Chinese.’

In the [Full.Match] conditions (14a, c), both conjuncts of the coordinate subject were congruent with the honourability of the verb, while those in the [Full.Mismatch] conditions (14b, d) were not. These full (mis)match conditions would enable us to explore how deviant the partial mismatch conditions in (13) are, as compared with the full (mis)match conditions in (14). In addition, we would be able to investigate if the markedness of nominal nim induces an effect that is parallel to that of verbal si (see (12b)).

Taken together, our experiment took the shape of a 2 × 4 design, with the two added levels of CONGRUENCE (i.e., Full.Match vs. Full.Mismatch added to the two partial mismatch conditions Local.Match vs. Local.Mismatch), but this was to explore our main concern more rigorously, focusing on the four partial honorific mismatch conditions.

Twenty-four lexically-matched sets of the eight conditions were constructed, counterbalanced across eight lists using a Latin square design so that a list has only one item from each set. Each list thus had 24 experimental items, together with 78 filler items (i.e., experimentals:fillers ≈ 1:3) of comparable length but with varying degrees of acceptability (see Goodall Reference Goodall and Goodall2021). In total, there were 102 sentences in each list.

3.2 Participants

Eighty-five self-reported native Korean speakers (age mean (SD): 21.738 (2.889)), who were all undergraduate students at a university in South Korea, were recruited. They received course credits for their online participation, which took about 10 minutes. Five participants were excluded because they did not appear to pay attention during the task, as described in section 3.3. Accordingly, only the responses from the remaining 80 participants (10 for each of the eight lists) were included in the analysis.

3.3 Procedure

We programmed the experiment with a web-based experiment platform PCIbex (Zehr and Schwarz Reference Zehr and Schwarz2018). The participants were asked to rate the acceptability of the sentence that was presented on a computer screen on a 1–7 Likert scale (1 = fully unnatural; 7 = fully natural). Sentences were presented one at a time in a pseudo-randomized order that was automatically generated by PCIbex at each run so that the experimental items were separated by three filler items. As a device to check if the participants were paying attention during the task, we used 20 filler items as the “gold standard” items. These gold standard items were 10 good and 10 bad filler items, whose expected value (i.e., 1 for the bad ones and 7 for the good ones) were obtained based on the results of our previous tests conducted on about 200 participants. For each gold standard item, we calculated the difference between each participant's response and its expected value. In order to compare the size of the differences that were either positive or negative numbers, we squared each of the differences and summed the squared differences for each participant. This gave us the sum-of-the-squared-differences value of each participant. We excluded any participants whose sum-of-the-squared-differences value was greater than two standard deviations away from the mean, suggesting that they were not paying attention during the task (see Sprouse et al. Reference Sprouse, Messick and Bobaljik2022).

3.4 Data analysis

Prior to analyzing the data, the raw judgment ratings, including both target items and fillers, were converted to z-scores in order to eliminate certain kinds of scale biases between participants (Schütze and Sprouse Reference Schütze, Sprouse, Podesva and Sharma2013). This procedure corrects the possibility that individual participants treat the scale differently, by standardizing all participants’ ratings to the same scale. We analyzed the data with linear mixed-effects regression (LMER) models estimated with the lme4 package (Bates et al. Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015) in the R software environment (R Core Team 2020). LMER models allow the simultaneous inclusion of random participant and random item variables (Baayen et al. Reference Baayen, Davidson and Bates2008). Throughout the process, we used the maximally convergent random effects structure with participant and item (Barr et al. Reference Barr, Levy, Scheepers and Tily2013). P-value estimates for the fixed and random effects were calculated by Satterthwaite's approximation (Kuznetsova et al. Reference Kuznetsova, Brockhoff and Christensen2017).

3.5 Results and discussion

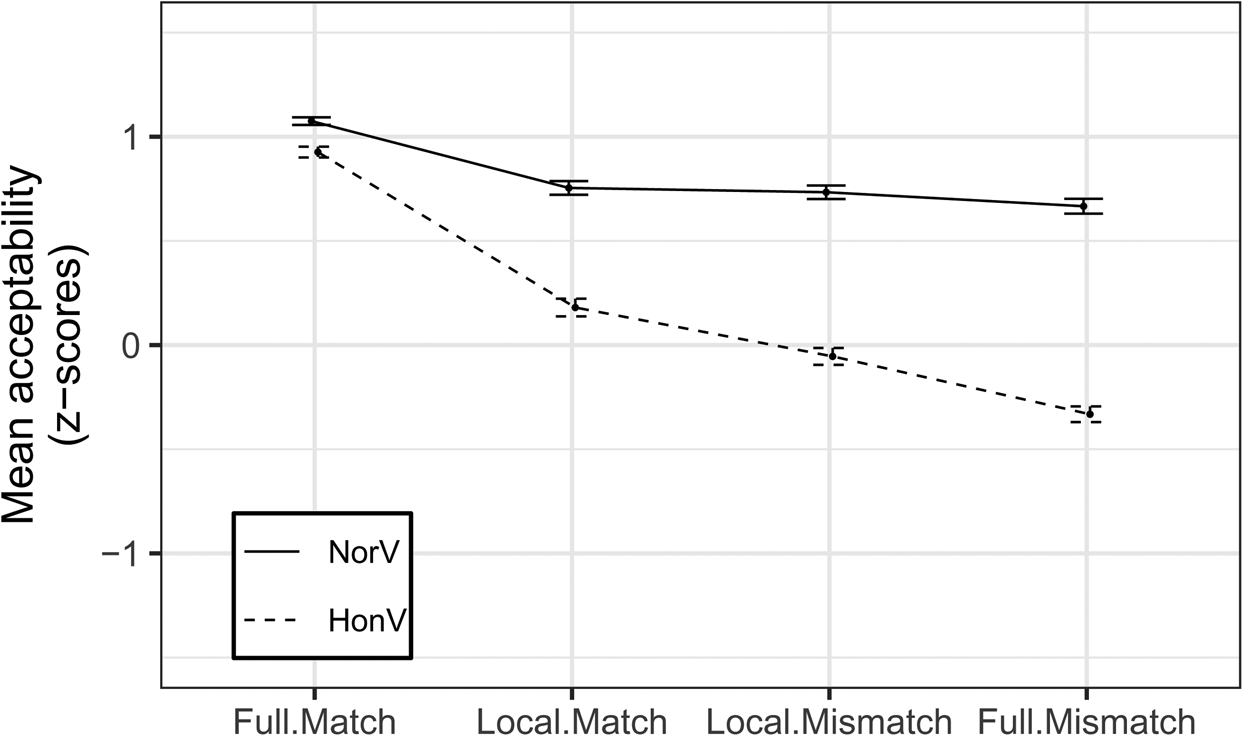

The responses from 80 participants, which amount to 240 tokens for each of the eight conditions (N = 1,920 in total) were analyzed. Figure 1 presents the mean of the z-scored ratings for the experimental conditions, consisting of the four partial honorific mismatch conditions (Local.Match and Local.Mismatch) of our main concern and the other four baseline conditions with full honorific (mis)matches. The PREDICATE effect is represented by a vertical separation between the lines, and the CONGRUENCE effect is represented by the downward slope of the lines.

Figure 1: Mean acceptability of experimental conditions (Error bars indicate SE)

As for our main interest, we ran a 2 × 2 LMER model within the four partial honorific mismatch conditions with PREDICATE and CONGRUENCE as fixed effects and the maximally convergent random effects structure (i.e., by-participant and by-item intercepts and a by-participant slope for each of the two fixed factors). There was a significant main effect of PREDICATE (β = −0.574, SE β = 0.065, t = −8.780, p < 0.001), but no main effect of CONGRUENCE (β = −0.021, SE β = 0.046, t = −0.447, p = 0.656). The interaction between PREDICATE and CONGRUENCE was significant (β = −0.214, SE β = 0.065, t = −3.309, p = 0.001), indicating that the difference in acceptability between the [Local.Match] vs. [Local.Mismatch] cases in the [HonV] conditions was greater than that in the [NorV] conditions, as predicted. This suggests that Korean honorification with coordinate subjects is triggered only when verbal si appears, and it shows the pattern of LCA.

This point becomes clearer when we consider the baseline conditions together. Both the [NorV] and [HonV] conditions showed a decrease in acceptability in the partial and full mismatch conditions relative to the [Full.Match] conditions. More precisely, the partial and full mismatch conditions among the [NorV] conditions all showed the statistically same degree of decrease in acceptability (confirmed by a series of one-way LMER models):

-

[NorV | Local.Match] vs. [NorV | Local.Mismatch] β = −0.021, SE β = 0.042, t = −0.494, p = 0.624;

-

[NorV | Local.Match] vs. [NorV | Full.Mismatch] β = −0.088, SE β = 0.048, t = −1.825, p = 0.076;

-

[NorV | Local.Mismatch] vs. [NorV | Full.Mismatch] β = −0.673, SE β = 0.053, t = −1.267, p = 0.211.

However, in contrast to the [NorV] cases, the [HonV] conditions showed uneven degradation: the [HonV | Local.Match] condition was significantly more acceptable than the [HonV | Local.Mismatch] condition (LMER: β = −0.234, SE β = 0.055, t = −4.286, p < 0.001) and the [HonV | Full.Mismatch] condition was further degraded than the [HonV | Local.Mismatch] condition (LMER: β = −0.278, SE β = 0.045, t = −6.169, p < 0.001). To summarize, unlike the [NorV] counterparts, the [HonV] mismatch conditions showed clear sensitivity to the locus of the honorific NP within coordinate subjects (i.e., the first conjunct vs. the last conjunct vs. neither), further suggesting that the subject honorific agreement in Korean is triggered by verbal si.

To the best of our knowledge, it has rarely been explored how deviant the acceptability of partial mismatches is, in comparison with that of full (mis)matches. This is true even for the research of gender agreement with reference to CCA (see Marušič et al. Reference Marušič, Nevins and Badecker2015), tested extensively across a range of languages. We suggest that Distributed Agree (e.g., Arregi and Nevins Reference Arregi and Nevins2012), which decomposes Agree into Match and Value, may provide an explanation. Especially as to the further degradation in the [HonV | Full.Mismatch] condition relative to the [HonV | Local.Mismatch] condition, both of which are expected to be ill-formed under the LCA pattern: they could be differentiated in terms of the success of Match and Value. While both Match and Value are unsuccessful in [Full.Mismatch], only Match, but not Value, is successful in [Local.Mismatch].

4. General discussion and syntactic analysis

The main findings of the experiment can be summarized as follows. First, the effect of partial and full mismatches was not sensitive to the locus of the honorific referent within coordinate subjects when conditioned by the honorific nominal nim, whereas it was sensitive when conditioned by the honorific verbal si. This suggests that nominal nim does not cause the same kind of honorification as the kind triggered by verbal si, thus confirming Kim and Sells's (Reference Kim and Sells2007) claim in (8b) that the nature of nominal honorification is different from that of verbal honorification.

Second, the partial honorific mismatches in Korean subject coordination did not cause degradation in a uniform way. The honorific mismatch of [HonV | Local.Match] was significantly more acceptable than that of [HonV | Local.Mismatch]. Regarding this, we can attribute the lower acceptability of [HonV | Local.Mismatch] to a violation of a certain syntactic principle: the lower acceptability might result from a failure in syntactic honorific agreement between an honorific verb and a potential goal NP. In this scenario, an uninterpretable [uHon] feature exists in honorific verbs, and it probes down for a suitable goal NP with [iHon] to value its unvalued honorific feature. This suggests that the probing process for agreement would be complicated once the probe meets the honorifically mixed coordinate nominals, under the assumption that coordinate phrases are somehow φ-deficient (Bošković Reference Bošković2009, Marušič et al. Reference Marušič, Nevins and Badecker2015).

From this perspective, we assume that Korean coordination heads are φ-deficient as well. The valuation of features on agreeing heads can take place in the postsyntactic component. This assumption has been called Distributed Agree (Arregi and Nevins Reference Arregi and Nevins2012, Bhatt and Walkow Reference Bhatt and Walkow2013, Marušič et al. Reference Marušič, Nevins and Badecker2015, Marušič and Nevins Reference Marušič, Nevins, Smith, Mursell and Hartmann2020). In order to keep the syntax exclusively operating on the basis of hierarchical structure, Marušič et al. (Reference Marušič, Nevins and Badecker2015) and others assume that linearity effects arise if agreement takes place in the postsyntactic component after linearization has taken place.

In these analyses, it is typically assumed that syntactic Agree is a two-step process. First, during the syntactic derivation, an agreeing syntactic head can establish a relation with a syntactic object, a process referred to as Match. The actual transfer of φ-features from the argument to the agreeing head, a process referred to as Value, takes place in the second step. In some cases, a situation can arise in which Match applies in narrow syntax and Value applies in PF, after linearization of constituents has taken place. This assumption straightforwardly models the intuition that it is the linear order that is responsible for CCA.

With an emphasis on two-step Agree and a φ-deficient conjunction head (&), we argue that Korean φ-agreement is triggered by Agr, which can only match the features on the &P, but cannot be valued by them (see the dashed line in (15)). In the Distributed Agree model, this deactivation does not have a fatal outcome since actual feature valuation can be postponed until after linearization. After linearization, the closest conjunct (i.e., the last conjunct) in (15) can value the φ-features on Agr:

(15) [&P NP1 [&’ NP2 &]] … Agr

Honorification with coordinate subjects, where the value of [Hon] on each conjunct apparently differs, shows patterns of variability and trade-offs between hierarchical and linear order.

Given this explanatory device, we propose that the experimental stimuli in (13) are derived in the following way:

(16)

a. [NorV | Local.Match]

[&P father-hon[iHon]-and John &]-nom Chinese-acc learn-past

b. [NorV | Local.Mismatch]

[&P John-and father-hon[iHon] &]-nom Chinese-acc learn-past

c. [HonV | Local.Match]

Match is successful!

Value is successful!

d. [HonV | Local.Mismatch]

Match is successful!

Value is not successful!

We posit that the high acceptability of [NorV | Local.Match] in (16a) (mean (SD): 0.754 (0.507)) and [NorV | Local.Mismatch] in (16b) (mean (SD): 0.734 (0.506)), is due to the lack of an honorific agreement process, since the nominal honorific feature within the coordinate subject is interpretable. As for the mid-range acceptability of [HonV | Local.Match] in (16c) (mean (SD): 0.180 (0.659)), we propose that [uHon] of the honorific verbal si in Agr matches the features on the &P, but cannot be valued by them spontaneously. Recall, however, that this process is not fatal according to the Distributed Agree model, and actual feature valuation takes place in the postsyntactic component. After linearization, the interpretable honorific feature in the closest conjunct (i.e., father -hon[iHon]) can value the uninterpretable honorific feature in the honorific verb (i.e., learn -hon[u Hon]- past). For the relatively low acceptability of [HonV | Local.Mismatch] in (16d) (mean (SD): −0.054 (0.625)), we propose that the derivation crashes because the uninterpretable honorific feature in the honorific verb (i.e., learn -hon[u Hon]- past) cannot be valued by the closest conjunct (i.e., John), which is a non-honorific referent. This suggests that CCA (or LCA) exists in Korean subject honorification.

So far, we have focused on NP coordination with respect to subject honorification. As suggested by a reviewer, our account can be carried over to honorific mismatches in VP coordination as well. Namai (Reference Namai2000) refutes the syntactic agreement approach in Japanese honorification because each of the conjoined VPs may independently contain an honorific form, causing honorific mismatches with an honorific subject. Namai argues that this fact indicates that there is no syntactic agreement in Japanese. Since the same goes for Korean, we will discuss this issue via the Korean data in (17):

(17) Kim sensayng-nim-i celm(-usi)-ko alumtau(-si)-ta.

Kim teacher-hon-nom young(-hon)-and beautiful(-hon)-dec

‘TeacherHon Kim is young(Hon) and beautiful(Hon).’(based on Namai (Reference Namai2000): (6) and (7))

Namai points out that it is not necessary for the honorific affix to appear in the two adjectival predicates in coordination. His argument is that if the honorific affix vouches for feature checking to take place, only the honorific verb forms (i.e., celm-usi-ko alumtau-si) in (17) would be ruled in. Yet the other combinations of verb forms in (17) (i.e., celm-ko alumtap, celm-usi-ko alumtap, and celm-ko alumtau-si) are equally, according to Namai, ruled in where no adjective or only one adjective checks [Hon] of the subject. Namai claims that this should cause featural crash. We respond to this criticism via the structure in (18):

(18) [TP Kim sensayng-[i Hon]nim1-i [&P [AgrP [VP t1 cemV] ([u Hon]usi)Agr-ko]

[AgrP [VP t1 alumtauV] ([u Hon]si)Agr ] &]]

We simply assume that in Korean, predicate-internal subjects are base-generated in each conjunct and then ATB-move to the surface subject position. When both conjuncts lack si, there would be no honorific agreement, since the honorific feature of nim in both conjuncts is interpretable. When either only the first conjunct or only the second conjunct contains si, [uHon] of si would be valued by [iHon] of its honourable subject. When both conjuncts have si, [uHon] of each si would be valued by [iHon] of each honourable subject.Footnote 9

Meanwhile, Kim and Sells (Reference Kim and Sells2007) argue that using honorification is a fundamentally pragmatic decision and not constrained by any inviolable grammatical principles. They focus on the privative and expressive nature of honorification. According to them, honorification has a privative specification: only the positive values exist. Semantically, honorification is part of the expressive content of an utterance as well as its regular propositional content (Potts and Kawahara Reference Potts, Kawahara and Young2004). In this view, the emotive meaning of honorification is incremental: more use is likely to strengthen the effect of deferential meaning (Choe Reference Choe2004). Although we agree with Kim and Sells's view that the incremental nature of honorification is not syntactic, we stress that using verbal si should be constrained by an inviolable grammatical principle, that is, Agree, in that it necessarily triggers subject honorification and thus always requires a local honourable referent.

Regarding our experimental data, Kim and Sells's (Reference Kim and Sells2007) pragmatic approach predicts that there would be no difference in acceptability ratings between partial mismatch conditions: as in [Local.Match] in (13c) and [Local.Mismatch] in (13d). In fact, Kim and Sells report that honorification with coordinate subjects may exhibit different acceptability, as seen in (19):

(19)

a. Pwumo-nim-kwa ai-tul-i hamkkey chwumchwu-(si)-essta.

parent-hon-and child-pl-nom together dance-(hon)-past

‘Parents and children danced together.’

b. Ai-tul-kwa pwumo-nim-i hamkkey chwumchwu-(si)-essta.

child-pl-and parent-hon-nom together dance-(hon)-past

‘Children and parents danced together.’ (modified from Kim and Sells Reference Kim and Sells2007: (24a))

According to them, some speakers prefer the presence of verbal si, but its absence can be acceptable. (Recall that our experimental findings attest that the presence of verbal si significantly degrades acceptability.) Kim and Sells (Reference Kim and Sells2007: fn. 11) mention in passing that some speakers judge (19b) to be more acceptable with verbal si than (19a). Importantly, these intuitions are partly compatible with our experimental findings in that the si-marked [Local.Match] condition was more acceptable than the si-marked [Local.Mismatch] condition. It is not clear, however, how the pragmatic approach can explain the attested difference between the partial mismatch conditions. One might suggest that the final conjunct in Korean coordination somehow receives “linguistic prominence”, but there is no obvious independent support for this with respect to verbal si.

Next, let us consider the structural effect in honorification, which could be a potential argument for the syntactic agreement approach over the pragmatic agreement approach. Chomsky (Reference Chomsky, Martin, Michaels and Uriageraka2000, Reference Chomsky and Kenstowicz2001) proposes that Agree takes place under Match, but not every matching pair induces Agree, In particular, Chomsky provides an argument in favour of separating Match from Agree which rests on the existence of what he calls “the defective intervention effect” (Chomsky Reference Chomsky, Martin, Michaels and Uriageraka2000: 123). Defective intervention arises when an element α matches the featural requirements of a probe P, but fails to agree with it. Crucially, in such cases, no more deeply embedded element β is accessible for checking, due to the presence of α.

As is well-known, Icelandic quirky subjects fail to trigger agreement on the finite verb, despite the fact that they behave for all other purposes as real subjects (as seen (Boeckx Reference Boeckx2000), as seen in (20).

Icelandic

(20) Stelpunum var hjálpað

girls.the.dat.PL.F was.3SG helped.SG.N

‘The girls were helped.’

Yet, the presence of quirky subjects blocks the establishment of an agreement relation between the verb and a nominative element as in (21), which is otherwise possible as in example (22):

Icelandic

(21)

*Mér fundust henni leiðast Þeir

me.dat seemed.3PL her.dat bore they.nom

‘I thought she was bored with them.’

Icelandic

(22)

Mér virðast Þeir vera skemmtilegir

me.dat seem.3PL they.nom be interesting.nom.PL.M

‘It seems to me that they are interesting.’

If Value were the only significant relation, the intervention effect in (21) would be unexpected since the quirky element cannot participate in Value. However, if Match exists independently of Value, the blocking effect in (21) makes sense. Being a closer-matching element, the quirky NP renders the nominative NP inaccessible to the finite verb.

Similarly, we argue that the failure of honorification in (23a), triggered by verbal si, with an honourable indirect (dative) NP in the presence of a higher non-honourable subject (nominative) NP is a case of defective intervention (Chomsky Reference Chomsky, Martin, Michaels and Uriageraka2000), as shown by the contrast between (23a) and (23b).

(23)

a. *John-i Kim-kyoswu-nim-eykey wain-ul sa-si-essta.

John-nom Kim-professor-hon-dat wine-acc buy-hon-past

‘John boughtHon professorHon Kim wine.’

b. Kim-kyoswu-nim-i John-eykey wain-ul sa-si-essta.

Kim-professor-hon-nom John-dat wine-acc buy-hon-past

‘ProfessorHon Kim boughtHon John wine.’

That the intervention is indeed defective is shown by the fact that the subject John in (23a) cannot trigger honorific agreement, but nevertheless prevents the indirect object Kim-kyoswu-nim from agreeing with si in Agr. Note that in order to capture the relevant defective intervention effect, it is crucial that the nominative element c-command the dative element which in turn c-commands the accusative element. This hierarchical nature of honorification suggests that the honorification agreement triggered by verbal si is syntactic. It is not obvious how the pragmatic agreement approach can account for this fact.

A reviewer questions our treatment of subject honorification as syntactic agreement because unlike obligatory agreement in English, honorific agreement is optional, and influenced by extra-grammatical factors. Although we agree that pragmatics plays an important role in honorification, the honorific mismatch within coordinate subjects is not easily explained by the pragmatic approach. In addition to the defective intervention effect of non-honourable referents and the super-additive degradation triggered by si, the CCA effect exhibited by honorific mismatches in coordination points us toward a syntactic approach instead. The honorific agreement triggered by verbal si is not optional; once verbal si is present, agreement is forced by the Agree theory of feature valuation.

Before concluding this section, we would like to point out an additional piece of evidence of the partly postsyntactic approach to Korean honorific coordination. It has been reported that when coordinated subjects consist of three conjuncts, Resolved Agreement and CCA are allowed in Serbo-Croatian, but Medial Conjunct Agreement (MCA) is not, as in (24).

Serbo-Croatian

(24) [Haljine, odela i suknje] su juče prodate / *prodata /

Dress.PL.F suit.PL.N and skirt.PL.F are yesterday sell.prt.PL.F sell.prt.PL.N

prodati.

sell.prt.PL.M

‘Dresses, suits and skirts were sold yesterday.’ (Murphy and Puškar Reference Murphy and Puškar2018: (10))

For instance, the feminine agreement in (24) reflects CCA (i.e., FCA or LCA), while the masculine agreement reflects Resolved Agreement. Murphy and Puškar (Reference Murphy and Puškar2018) observe that the neuter agreement is not acceptable in (24).

The MCA pattern is noteworthy because the purely syntactic approach and the partly postsyntactic approach make different predictions for the 2 × 3 minimal set in (25a–f).

(25)

a. [NorV | Last]

John-kwa Mary-wa ape-nim-i cwungkwuke-lul paywu-essta.

John-and Mary-and father-hon-nom Chinese-acc learn-past

‘John, Mary, and fatherHon learned Chinese.’

b. [NorV | Medial]

John-kwa ape-nim-kwa Mary-ka cwungkwuke-lul paywu-essta.

John-and father-hon-and Mary-nom Chinese-acc learn-past

‘John, fatherHon, and Mary learned Chinese.’

c. [NorV | First]

Ape-nim-kwa John-kwa Mary-ka cwungkwuke-lul paywu-essta.

father-hon-and John-and Mary-nom Chinese-acc learn-past

‘FatherHon, John, and Mary learned Chinese.’

d. [HonV | Last] (i.e., LCA)

John-kwa Mary-wa ape-nim-i cwungkwuke-lul paywu-si-essta.

John-and Mary-and father-hon-nom Chinese-acc learn-hon-past

‘John, Mary, and fatherHon learnedHon Chinese.’

e. [HonV | Medial] (i.e., MCA)

John-kwa ape-nim-kwa Mary-ka cwungkwuke-lul paywu-si-essta.

John-and father-hon-and Mary-nom Chinese-acc learn-hon-past

‘John, fatherHon, and Mary learnedHon Chinese.’

f. [HonV | First] (i.e., FCA)

Ape-nim-kwa John-kwa Mary-ka cwungkwuke-lul paywu-si-essta.

father-hon-and John-and Mary-nom Chinese-acc learn-hon-past

‘FatherHon, John, and Mary learnedHon Chinese.’

The partly postsyntactic approach predicts that the LCA pattern ([HonV | Last]) will be more acceptable than the other two, namely, the MCA ([HonV | Medial]) pattern and the FCA ([HonV | First]) pattern, because the last conjunct is the linearly closest to the honorific verb. In contrast, the purely syntactic approach predicts that the FCA pattern will be more acceptable than the other two, because the first conjunct is structurally higher than the medial and last conjuncts in Korean. In short, according to the partly postsyntactic approach, the MCA pattern is expected to be less acceptable than the LCA pattern, while according to the purely syntactic approach, it is expected to be less acceptable than the FCA pattern.

To test these predictions, we ran a further experiment regarding the honorific mismatch among three conjuncts. The responses from 48 participants (i.e., eight participants for each of the six Latin square lists), which amount to 192 tokens for each of the six conditions (N = 1,152 in total), were analyzed. Figure 2 presents the mean of the z-scored ratings for the six experimental conditions.

Figure 2: Mean acceptability of experimental conditions (Error bars indicate SE)

According to pairwise comparisons, there was no statistical difference among the normal verb conditions in (25):

-

[NorV | Last] vs. [NorV | Medial] (p = 0.484),

-

[NorV | Last] vs. [NorV | First] (p = 0.651),

-

[NorV | Medial] vs. [NorV | First] (p = 0.251).

Meanwhile, [HonV | Last] was significantly more acceptable than [HonV | Medial] and [HonV | First], but there was no significant difference between [HonV | Medial] and [HonV | First]:

-

[HonV | Last] vs. [HonV | Medial] (β = −0.237, SE β = 0.063, t = −3.756, p = 0.001),

-

[HonV | Last] vs. [HonV | First] (β = −0.220, SE β = 0.067, t = −3.285, p = 0.002),

-

[HonV | Medial] vs. [HonV | First] (p = 0.765).

The above statistical analyses were obtained from corresponding LMER models.

The results indicate that the LCA pattern was more acceptable than the FCA and MCA patterns without any significant difference in acceptability ratings between the latter two patterns, as predicted by the partly postsyntactic approach. We thus conclude that the partly postsyntactic approach to Korean honorific coordination is preferable over the purely syntactic approach.

One might argue that Bošković's (Reference Bošković2009) purely syntactic approach to Serbo-Croatian gender agreement can explain the LCA pattern observed here. Bošković claims that under the multiple-Spec structure in (26), every NP in Spec of &P is equidistant from the probe, so the first and medial conjuncts could not function as the suitable goal in Serbo-Croatian, leaving only the last conjunct as the target of Agree.

(26) [&P Spec-NP1 [&P Spec-NP2 [&’ & Compl-NP3 ]]] (Bošković Reference Bošković2009: (33))

Recall from section 2.1 that under Bošković's account, the LCA pattern is derived due to the lethal ambiguity that deactivates the first conjunct for Agree: since the first conjunct can be extracted ignoring the Coordinate Structure Constraint in Serbo-Croatian, the [+EPP]-bearing probe cannot decide which target, the first conjunct or the &P, should be pied-piped. Similarly, the medial conjunct in (26) should be deactivated for Agree in order to derive the LCA pattern.

However, this account does not transfer straightforwardly to Korean honorification in (25), as illustrated in (27), because the first and medial conjuncts cannot be extracted in Korean (see Stjepanović (Reference Stjepanović1999) for no-medial-conjunct extraction even in Serbo-Croatian). Nevertheless, there arises a similar ambiguity if we assume the multiple-Spec structure in (27):

(27) [AgrP [vP [&P NP1 [&’ NP2 [&’ NP3 &]]] … v] Agr[u Hon]]

Given that the &P cannot be targeted by the probe [uHon], the most accessible (i.e., the highest) conjunct should function as the goal. This time, the first conjunct NP1 and the medial conjunct NP2 are assumed to be equally accessible, since the two specifiers are equidistant from the probe. If, as Bošković (Reference Bošković2009) claimed, this ambiguity was lethal as well, the first and medial conjuncts would fail to function as the goal, and therefore, the last conjunct would be the target of Agree, deriving the LCA pattern.Footnote 10

If this is so, an important empirical prediction can be made. Bošković's (Reference Bošković2009) account would not explain our main finding, to wit that the last conjunct should be targeted for Agree when there are only two conjuncts in coordinate subjects, as illustrated in (28):

(28) [AgrP [vP [&P NP1 [&’ NP2 &]] … v] Agr[u Hon]]

In this case, unlike in (26) and (27), there is no ambiguity that may deactivate the first conjunct, because the first conjunct NP1, as the only specifier, is structurally higher than the last conjunct NP2, which is the complement. In short, although Bošković's account might provide a way to explain the LCA pattern in (27), it still fails to account for why the LCA pattern arises in (28). Therefore, we conclude that the partly postsyntactic approach pursued is empirically more viable than the purely syntactic approach.

To summarize, our analysis of Korean honorification corroborates the existence of CCA, which has been argued to exist cross-linguistically. We have argued that the best way to account for Korean honorification with coordinate subjects is by postulating an unvalued honorific feature on a functional head Agr that matches a goal NP via probing in narrow syntax, but which gets valued in the postsyntax. Furthermore, we have shown that the distribution of an honorific NP among multiple conjuncts in Korean shares properties with South Slavic gender agreement systems.Footnote 11

5. Conclusion

Although honorific verbal agreement with coordinate subjects is syntactically conditioned, rather than adopting a purely syntactic approach (Bošković Reference Bošković2009), we have argued that it is also postsyntactically conditioned. This was motivated by the fact that coordinate subject honorification is sensitive to linear order. We proposed a partly syntactic and partly postsyntactic approach to Korean honorification that has a great deal in common with Marušič et al.'s (Reference Marušič, Nevins and Badecker2015) approach to South Slavic gender agreement. We have argued that Korean subject honorification must carry verbal si, contra the view (in Yoon Reference Yoon1990 and Choi and Harley Reference Choi and Harley2019) that it must carry honorific nominals. We argued that Korean subject honorification should be treated as syntactic agreement, following a growing literature on honorification-as-agreement (Boeckx and Niinuma Reference Boeckx and Niinuma2004; Kishimoto Reference Kishimoto2010, Reference Kishimoto2012).

Our proposal has certain theoretical implications. First, the experimental results confirm Kim and Sells's (Reference Kim and Sells2007) insight that nominal honorification differs from verbal honorification. This insight is bolstered by the privative property of the honorific feature [Hon]. The distribution of honorific mismatches is best explained by a grammatical account that incorporates the distinctness of uninterpretable features [uHon] of honorific verbal morphemes vs. interpretable features [iHon] of honorific nominal referents. Second, we suggested that the honorific agreement triggered by honorific verbal morphemes is syntactic and obligatory, whereas the honorific agreement triggered by honorific nominal referents is not. Finally, we showed that Korean honorification with coordinate subjects is an instance of the closest conjunct agreement as can be seen in other languages such as Hindi (Bhatt and Walkow Reference Bhatt and Walkow2013), Serbo-Croatian (Bošković Reference Bošković2009, Murphy and Puškar Reference Murphy and Puškar2018), and Slovenian (Marušič et al. Reference Marušič, Nevins and Badecker2015).