The purpose of the present research is to explore when and why managers sometimes take steps to informally compensate subordinates whom they deem to have been unfairly treated by senior leaders. These Robin Hood behaviors consist of allocating the victim something extra that belongs to the company and without the consent of upper management (Nadisic, Reference Nadisic, Gilliland, Steiner and Skarlicki2008). In principle, Robin Hoodism can involve a wide range of behaviors and people (e.g., coworkers, customers). In the present article, we focus on managers as “Robin Hoods.” We choose this focus because the relationship with one’s manager is a particularly important workplace relationship for employees (Dulebohn, Bommer, Liden, Brouer, & Ferris, Reference Dulebohn, Bommer, Liden, Brouer and Ferris2012) and because managers as Robin Hoods illustrate an important conundrum: when employees are deemed to be unfairly harmed by the organization, managers can be “stuck in the middle” and look for unconventional ways to reconcile their responsibilities. We introduce the term managerial Robin Hoodism (MRH) and provide theory about how this phenomenon relates to different types of justice violations and moral concerns. MRH has three defining characteristics: 1) it is triggered when a manager perceives that a subordinate has been treated unfairly, 2) it is an attempt to somehow compensate the victim, and 3) this attempt at compensation can involve rule breaking.

Drawing from deontic justice theory (Folger & Salvador, Reference Folger and Salvador2008), we propose and test a theory of MRH. We begin by examining the premise of our definition: that managers engage in Robin Hood behaviors in response to an injustice committed by upper management (study 1). We then take a closer look at the different types of justice that can underlie MRH, arguing that violations of two types of justice, distributive and interpersonal, are more likely to motivate MRH than violations of other types, such as procedural and informational (study 2). Finally, the results of study 1 suggest that the managers’ Robin Hood efforts are motivated by moral concerns about their subordinates’ mistreatment. To test the validity of this reported motive, we integrate research on MRH with moral identity and find that, indeed, MRH occurs as a function of moral identity (studies 3 and 4).

Through this research, we make three contributions. Our first contribution consists of defining and articulating the construct of MRH. Managers acting as Robin Hoods may be manifesting elements of “constructive deviance” (Warren, Reference Warren2003), “pro-social rule breaking” (Morrison, Reference Morrison2006), “positive deviance” (Spreitzer & Sonenshein, Reference Spreitzer and Sonenshein2004), or “restorative justice” (Goodstein & Aquino, Reference Goodstein and Aquino2010). Although related to other constructs, MRH is unique in several respects. MRH focuses on the direct supervisor’s actions and does not seek to build a new value consensus, as does research on restorative justice, nor does MRH necessarily seek to protect the organization (Umphress & Bingham, Reference Umphress and Bingham2011; Umphress, Bingham, & Mitchell, Reference Umphress, Bingham and Mitchell2010). Second, we shed light on the motives underlying MRH. Although MRH can be undertaken for various reasons, we propose and find that MRH can be motivated by moral concerns, such as a desire to restore fairness. Though MRH might seem unethical to an observer, it may be perceived as highly ethical to the manager involved because it originates in the desire to correct a justice violation. Third, our findings have implications for organizational justice research. We find that the different types of justice do not share a common nomological net. Violations of interpersonal and distributive justice are more likely to engender MRH than are violations of procedural and informational justice. Additionally, the moral salience of the justice types also appears to differ. Interpersonal justice appears to be more directly relevant to morality when compared to distributive justice (Scott, Colquitt, & Paddock, Reference Scott, Colquitt and Paddock2009). Fourth, as we investigate the role of moral concerns for MRH, we also contribute to emerging research on moral identity (Aquino & Reed, Reference Aquino and Reed2002). We find that moral identity appears to impact MRH through changing the focus away from instrumental concerns and toward moral concerns, at least when interpersonal justice is involved. This is true both for trait and for situationally primed moral identity.

A THEORY OF MANAGERIAL ROBIN HOODISM

Folger (Reference Folger, Gilliland, Steiner and Skarlicki2001) proposed that people often feel a moral duty to rectify a justice violation. Folger and Salvador (Reference Folger and Salvador2008) labeled this experience deontic justice, from the Greek word deon, which refers to one’s obligation or duty. The deontic model proposes that when mistreatment violates norms of moral and social conduct, victims and observers are motivated to address the wrong (Folger & Skarlicki, Reference Folger, Skarlicki, Fox and Spector2005, Reference Folger, Skarlicki, Gilliland, Steiner and Skarlicki2008; Rupp & Bell, Reference Rupp and Bell2010). According to deontic justice research, one possible response is to retaliate against the perpetrator (Barclay, Skarlicki, & Pugh, Reference Barclay, Skarlicki and Pugh2005; Folger, Ganegoda, Rice, Taylor, & Wo, Reference Folger, Ganegoda, Rice, Taylor and Wo2013; Skarlicki, O’Reilly, & Kulik, Reference Skarlicki, O’Reilly, Kulik, Cropanzano and Ambrose2015). Previous research has found that retribution is likely even though it can be risky and personally costly (Christian, Christian, Garza, & Ellis, Reference Christian, Christian, Garza and Ellis2012; Cropanzano, Goldman, & Folger, Reference Cropanzano, Goldman and Folger2003, Reference Cropanzano, Goldman and Folger2005; Folger & Glerum, Reference Folger, Glerum, Cropanzano and Ambrose2015; Rupp & Bell, Reference Rupp and Bell2010; Skarlicki, Ellard, & Kelln, Reference Skarlicki, Ellard and Kelln1998; Skarlicki & Folger, Reference Skarlicki, Folger, Griffin and O’Leary-Kelly2004; Skarlicki, van Jaarveld, & Walker, Reference Skarlicki, van Jaarveld and Walker2008; Turillo, Folger, Lavelle, Umphress, & Gee, Reference Turillo, Folger, Lavelle, Umphress and Gee2002). While research on third-party reactions to justice violations has focused mainly on retribution, deontic justice theory suggests that another option is possible.

Though not widely tested, observers can engage in compensatory actions to provide benefits to the victims (Mitchell, Vogel, & Folger, Reference Mitchell, Vogel, Folger, Giacalone and Promislo2012; Priesmuth, Mitchell, & Folger, Reference Priesmuth, Mitchell, Folger, Bowling and Hershcovis2017). Empirical evidence supports this contention (Darley & Pittman, Reference Darley and Pittman2003; de Kwaadstenient, Rijkhoff, & van Dijk, Reference de Kwaadstenient, Rijkhoff and van Dijk2013; Mulder, Verboon, & De Cremer, Reference Mulder, Verboon and De Cremer2009). Building on this idea, we propose that MRH can occur when a manager wishes to compensate an employee for a perceived injustice. Research has observed managers reallocating resources outside of the formal reward system to address inappropriate treatment (Henry, Reference Henry1981; Mars & Nicod, Reference Mars, Nicod and Henry1981). At times, these actions were ethically dubious because the benefits (e.g., bonuses, training) were allocated in a manner that was not for their intended purpose (Ditton, Reference Ditton1977).

Managerial Robin Hoodism and the Different Types of Justice

It is unlikely that all types of justice violations to a subordinate evoke MRH to an equal degree or in the same way. We argue that MRH is a compensation mechanism typically aimed at correcting injustice in relation to outcomes. The organizational justice literature has typically differentiated between four types of justice violations: distributive (concerning outcome allocations), interpersonal (related to treatment from others), procedural (related to fairness of the process), and informational (related to information sharing) (see Colquitt, Reference Colquitt2001).

Following Greenberg’s (Reference Greenberg and Cropanzano1993) reasoning, we argue that the first two types of justice pertain to outcomes and are therefore particularly likely to trigger MRH. Specifically, MRH is well adapted to correct distributive justice violations because “taking from the rich and giving to the poor” is inherently distributive. As reported earlier, considerable empirical evidence has shown that managers can attempt to compensate employees for such things as unfairly low wages by providing them with alternative forms of compensation (e.g., Ditton, Reference Ditton1977; Henry, Reference Henry1981). Less obvious, though for similar reasons, MRH can also be appropriate for correcting interpersonal justice violations. This is because both distributive and interpersonal injustices concern a loss of outcome: one material, the other socioemotional (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Vogel, Folger, Giacalone and Promislo2012). Interpersonal justice violations are “more recognizable as a threat to a person’s core identity as a human being” (O’Reilly, Aquino, & Skarlicki, Reference O’Reilly, Aquino and Skarlicki2016: 173). As a result, managers can experience empathy when they see someone experience an interpersonal injustice. This can activate the desire to respond (Leung, Chiu, & Au, Reference Leung, Chiu and Au1993; Vega & Comer, Reference Vega and Comer2005). Empirical evidence has supported this reasoning. For example, Okimoto (Reference Okimoto2008) reported that benevolent monetary compensation was used by managerial authorities to address employees’ identity threats resulting from injustices. Similarly, Reb, Goldman, Kray, and Cropanzano (Reference Reb, Goldman, Kray and Cropanzano2006) found that monetary solutions were suitable to atone for interpersonal injustices.

Procedural justice violations, in contrast, should be less likely to reliably trigger MRH. Procedural injustices arise from violations of the fairness of the decision processes. Brockner and Wiesenfeld (Reference Brockner and Wiesenfeld1996), however, showed that procedural violations had significantly less impact on justice reactions when the outcomes associated with those procedures were favorable (vs. unfavorable). According to this thinking, there is less reason to respond to an unfair procedure, unless it results in a material or socioemotional loss (Brockner, Reference Brockner2002). Although procedural justice is certainly important, it is less directly related to an outcome than are distributive and interpersonal justice (Greenberg, Reference Greenberg and Cropanzano1993).

Hypothesis 1: Distributive and interpersonal injustice are more predictive of managerial Robin Hood behaviors than is procedural injustice.

Moral Concerns and the Types of Justice

All types of justice violations do not trigger moral concerns to the same degree. Interpersonal justice is especially pertinent to moral thinking, whereas distributive justice is less so. If MRH can be undertaken for moral reasons, then this distinction is important. Folger (Reference Folger, Gilliland, Steiner and Skarlicki2001), for example, argued that although different justice violations can trigger moral concerns, interpersonal violations are especially likely to do so for three reasons: accountability, intention, and volition. According to Folger (Reference Folger, Gilliland, Steiner and Skarlicki2001), the source of an interpersonal justice violation tends to be readily identifiable (i.e., accountability) because there is likely to be a single actor displaying an independent behavior. As for intention, interpersonal justice is high on this dimension as well. Scott et al. (Reference Scott, Colquitt and Paddock2009) maintained that an interpersonal action tends to be the least constrained type of justice behavior. Consequently, when individuals violate interpersonal justice, it allows observers to make less ambiguous inferences about their underlying motives. Interpersonal justice also appears to be especially volitional, or due to the actor’s personal choice. In line with these arguments, two studies by O’Reilly et al. (Reference O’Reilly, Aquino and Skarlicki2016) showed that observing interpersonal justice violations can lead to moral anger, especially among those who are high in moral identity.

Folger (Reference Folger, Gilliland, Steiner and Skarlicki2001) maintained that distributive justice is lower on accountability, intention, and volition in comparison to interpersonal justice. As for accountability, the source of an unfavorable allocation is difficult to pinpoint, as it could be due to the different individual decision maker, a policy, or circumstances (e.g., the economy, government regulation). This list of potential contributing factors and sources in turn implies that intentions and volition may be low as well. Scott and colleagues (Reference Scott, Colquitt and Paddock2009) argued that distributive actions tend to be the most constrained type of justice behavior. Hence distributive justice leads to murkier attributions as to the actor’s underlying motives. To clarify, this is not to say that distributive justice violations will not trigger moral outrage and indignation—we know they do (see Turillo et al., Reference Turillo, Folger, Lavelle, Umphress and Gee2002). Our theoretical arguments, however, suggest that interpersonal justice violations are likely to produce a relatively stronger and more reliable moral reaction to unfairness than distributive justice violations (Mikula, Petri, & Tanzer, Reference Mikula, Petri and Tanzer1990).

Individual Differences in Moral Identity

People differ with regard to how central moral concerns are for them. Moral identity is defined as the degree to which moral concerns are a salient aspect of one’s self-identity (Aquino & Reed, Reference Aquino and Reed2002; Aquino, Reed, Stewart, & Shapiro, Reference Aquino, Reed, Stewart, Shapiro, Gilliland, Steiner, Skarlicki and van den Bos2005; O’Reilly et al., Reference O’Reilly, Aquino and Skarlicki2016). A moral identity is only one possible way of viewing the self, though it can be an important one (Blasi, Reference Blasi, Kurtines and Gewirtz1984; Jennings, Mitchell, & Hannah, Reference Jennings, Mitchell and Hannah2015; Shao, Aquino, & Freeman, Reference Shao, Aquino and Freeman2008). Moral identity has often been treated as an individual difference variable, with some individuals being higher on this attribute than others. However, there is more to the story. According to the social-cognitive perspective, which guides much moral identity research, moral identity can also be primed or activated by situational cues (Aquino, Freeman, Reed, Lim, & Felps, Reference Aquino, Freeman, Reed, Lim and Felps2009; Shao et al., Reference Shao, Aquino and Freeman2008).

Moral identity should moderate moral reactions for two reasons. First, individuals possess a self-consistency motive. Because of this, those with a strong moral identity will behave in a manner that matches their actions to their self-concepts (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Aquino and Freeman2008). Second, people with strong moral identity are more sensitized to events that violate moral and social norms because the moral ramifications of their behavior are highly salient to them (Jennings et al., Reference Jennings, Mitchell and Hannah2015). This sensitivity motivates them to act out of a moral motive. Moral identity is likely to have implications for MRH. Aquino and colleagues (Reference Aquino, Freeman, Reed, Lim and Felps2009) found that in an unjust situation, employees’ moral identity was positively related to breaking rules to “even the score.” Reynolds and Ceranic (Reference Reynolds and Ceranic2007) showed that moral identity interacted with moral judgments to predict when managers would be likely to give employees time off in response to mistreatment. High moral identifiers were more likely to demonstrate these tendencies relative to low moral identifiers.

Given the more apparent moral concerns associated with an interpersonal as compared to a distributive justice violation, individuals with high moral identity should be particularly reactant to interpersonal justice violations (cf. Leung & Tong, Reference Leung, Tong, Gilliland, Steiner and Skarlicki2003; O’Reilly et al., Reference O’Reilly, Aquino and Skarlicki2016; Skarlicki et al., Reference Skarlicki, van Jaarveld and Walker2008). This is because high moral identity managers are especially sensitive to morally charged violations, such as interpersonal injustices. Given the high moral sensitivity of interpersonal justice violations, low interpersonal justice should be especially likely to trigger MRH no matter the level of distributive justice. We propose that moral identity makes salient the moral issues inherent in interpersonal justice violations. Distributive justice, in contrast, should be less consistently related to MRH even when moral identity is high. As noted, moral identity can be observed as an individual difference and could also be activated by the situation, such as through a cue or prime (Aquino et al., Reference Aquino, Freeman, Reed, Lim and Felps2009; Aquino & Reed, Reference Aquino and Reed2002; Shao et al., Reference Shao, Aquino and Freeman2008). This environment-induced moral identity should produce a similar three-way interaction.

Turning to low moral identity, managers care about justice for a number of reasons, including relational considerations and instrumental concerns. These reasons should come to the fore when moral identity is low; that is, managers who have low levels of moral identity should still be motivated to rectify low justice, but not primarily due to concerns about moral issues. They would likely attend to instrumental or relational issues, and these motives should be relevant to roughly equal degrees. Thus, when managers have low moral identities, distributive and interpersonal justice violations should affect their behavior similarly: both should be related to MRH in the same way and to about the same degree.

Theoretical Summary

Managers engage in MRH to compensate a subordinate who is deemed to have been unjustly treated (study 1). MRH is more likely to occur amid outcome-oriented forms of justice violations, such as distributive and interpersonal justice, and is less likely with process-oriented forms, such as procedural justice (study 2). Finally, the two outcome-oriented types of justice differ with respect to their moral relevance, with interpersonal justice being more likely to trigger moral concerns than distributive. As a consequence, the effect of injustice on MRH is proposed to occur as a function of the strength and salience of the manager’s moral identity (studies 3 and 4). When moral identity is high, interpersonal justice predicts MRH regardless of the level of distributive justice. When moral identity is low, the two types of justice similarly predict MRH.

Hypothesis 2: Moral identity moderates how strongly managers respond to different types of justice violations through Robin Hoodism. When moral identity is low, distributive and interpersonal justice violations to a subordinate independently predict MRH (i.e., Robin Hoodism will be highest when both interpersonal and distributive injustice are high). When moral identity is high, interpersonal injustices toward a subordinate will lead to high levels of MRH independent (i.e., at both low and high levels) of distributive justice.

PRELIMINARY STUDY 1: INITIAL INVESTIGATION

Study 1 was a preliminary investigation to explore MRH from the perspective of those who are likely to use it and give realistic descriptions of their experiences (O’Reilly, Reference O’Reilly1991), namely, the supervisors themselves. Our goals were 1) to confirm that the phenomenon is common by looking at it in its natural ecology, 2) to identify specific behaviors that managers use when they act as Robin Hoods, 3) to collect preliminary evidence about the types of justice violations on subordinates that may trigger MRH, and 4) to assess whether those who choose to engage in MRH may sometimes be motivated by moral reasons. We conducted interviews with managers and then coded these data using categories representing the three concepts of interest: whether and how managers engage in MRH, types of justice violations that trigger this response, and whether moral motives were part of the impetus to engage in these behaviors (Bryman & Bell, Reference Bryman and Bell2003; Mayring, Reference Mayring2014; Schreier, Reference Schreier2012).

Method

Participants

One-to-one interviews were conducted with thirty-five managers—twenty men and fifteen women—of a European company. The firm employs approximately 550 workers and is specialized in the operations and logistics of book publishing. Our sample of thirty-five managers represented 85.4 percent of the first-line (team) and second-line (departmental) managers of the firm. Twenty-six of the managers (74.2 percent) worked in the factory, and nine managers (25.7 percent) oversaw administrative functions.

Data Collection

Interviews lasted from fifteen minutes to two hours (fifty minutes on average). Participants were asked three questions: 1) “Can you recall one or more events that you have perceived as an injustice against one (or more) of your subordinates?” 2) “How did you (as the manager) react to this injustice?” and 3) “What was your motivation to react in the way you did?” Managers were invited to discuss multiple events if they arose. The first question was asked to contextualize the second question. We aimed to help managers provide their answers in relation to a specific situation so we could identify justice violation types. We posed the second question to uncover whether managers indeed used MRH as a strategy and to identify specific behaviors managers used when they acted as Robin Hoods. We did not ask specifically about any kind of strategy. The intent of the third question was to gain insights into the self-reported motives underlying the managers’ reactions.

Coding Procedure and Data Analysis

All thirty-five interviews were coded by two of the authors. Participants recounted seventy-four incidents, and each incident represented the unit of analysis. Given our precise goals for this study, we developed a coding scheme prior to the interviews. Following Mayring (Reference Mayring2014) and Potter and Levine-Donnerstein (Reference Potter and Levine-Donnerstein1999), we used existing theory to identify key concepts as initial coding categories. First, we coded each incident for the type of justice using Colquitt’s (Reference Colquitt2001) categorization: distributive (outcomes), procedural (process), interpersonal (dignity and respect), and informational (explanation or rationale) justice. We also coded for the source of mistreatment according to the transgressor’s position in the hierarchy (upper management, manager, or coworker).

Second, to code for the underlying motives for MRH, we used the categorization of motives previously described in the organizational justice literature (for a review, see Greenberg & Colquitt, Reference Greenberg and Colquitt2005): instrumental concerns, relational concerns, and moral concerns. Managers motivated by instrumental concerns (Thibaut & Walker, Reference Thibaut and Walker1978) may want to address these problems to improve their subordinates’ performance at work, which helps managers reach their own objectives (Greenberg, Reference Greenberg1990). Relational concerns refer to concerns about relationships and social standing (Tyler & Lind, Reference Tyler, Lind and Zanna1992). Thus managers can be motivated by building strong relational bonds in their working teams, as these are powerful sources of social identity for them. Finally, managers motivated by deontic concerns (Folger, Reference Folger, Gilliland, Steiner and Skarlicki2001) may see fairness as a valuable end in itself independently of the material or relational benefits they can get from it.

Last, regarding coding for the managers’ reactions to justice violations, we used Nadisic’s (Reference Nadisic, Gilliland, Steiner and Skarlicki2008) definition of MRH as the conceptual standard to determine whether a specific reaction was an example of this behavior. In particular, we coded whether the manager allocated something extra to the victim of mistreatment that 1) belonged to the company and 2) was not intended to be used in reaction to a justice violation. Taking 2) into account allowed us to include the “rule breaking” feature of our definition in our coding. Because, for the purpose of this study, we were not concerned with the other types of reactions a manager can have, we only present here the extent to which managers used Robin Hoodism when witnessing a justice violation on a subordinate. We were interested in the links between justice violations, the use of MRH, and the managers’ motives. Thus we counted frequencies with which each type of mistreatment and each type of manager’s motive triggered MRH. The results are presented in the next section.

Consistent with best practices (e.g., Banks, Pollack, Bochantin, Kirkman, Whelpley, & O’Boyle, Reference Banks, Pollack, Bochantin, Kirkman, Whelpley and O’Boyle2016; Whiting & Maynes, Reference Whiting and Maynes2016), we calculated the interrater agreement on the final coding scheme using the Fleiss method to estimate Cohen’s kappa (Cohen, Reference Cohen1960). The overall interrater agreement (.91) exceeded the threshold (.75), which is thought to indicate excellent reliability (Fleiss, Reference Fleiss1981). In case of a disagreement, the two coders engaged in a discussion to gain consensus.

Results and Discussion

Findings from study 1 were consistent with our theoretical position. MRH was mentioned as a remedy in thirty incidents (18 percent of the reported managers’ reactions). Almost half of the managers (seventeen out of thirty-five) reported acting as Robin Hoods in one or several incidents. For example, one group of workers felt unfairly treated because they were not given extra compensation after working through a strike. Their manager gave them two days off to alleviate the injustice they felt. Another manager responded to complaints from subordinates who had worked especially hard for three months. They found it unfair that they had not received an extra bonus. The manager allocated to them a special dust bonus (reserved for employees who work in dust) even if her team had not worked in dust. Next, we explored which source of injustice (upper management, line managers, or the employee’s coworkers) triggered managers to act as Robin Hoods. The results showed that MRH was used to correct perceived injustices stemming from senior managers (72 percent of incidents) and other line managers (28 percent of incidents). None of the challenges perpetrated by coworkers were corrected with the use of MRH.

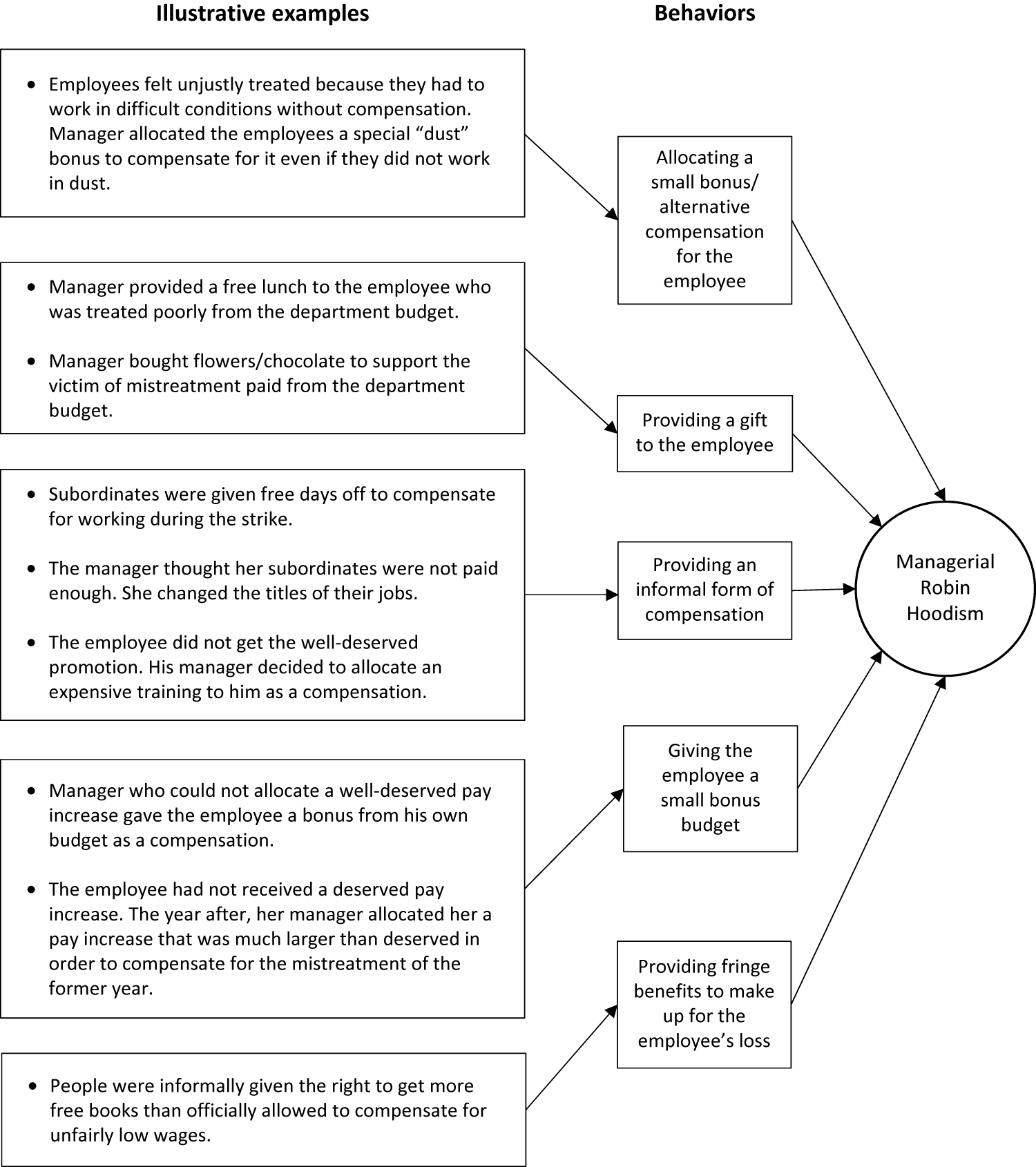

We identified five behaviors that managers use when they act as Robin Hoods (see Figure 1). Specifically, all five behaviors represent remedies that compensate victims and are not divulged to upper management; these include 1) allocate a small bonus/alternative compensation, 2) provide a gift paid out of the department budget, 3) give an informal form of compensation, 4) give a small bonus budget, and 5) provide fringe benefits to make up for the employee’s loss. For example, several managers said that according to the rules, they should only allocate a bonus for specified work performance, but acknowledged that they instead have given a bonus to subordinates who had not met those criteria but who had suffered an injustice. One interviewee even awarded an employee a raise that was not approved by upper management because he thought upper management had treated the employee unfairly by refusing the raise. Another example of MRH consisted of providing additional vacation time to employees without upper management consent.

Figure 1: Examples for Managerial Robin Hoodism (Study 1).

We further investigated which type of justice violations triggered managers to act as Robin Hoods. Seventy-seven percent of all Robin Hood behaviors occurred in response to distributive justice violations, 15 percent were in response to interpersonal justice violations, and 8 percent were in response to procedural justice violations. In contrast, as we expected, informational justice violations were not reported as evoking Robin Hood behaviors among our participants.

As for the managers’ motives for engaging in MRH, of the total Robin Hood incidents, 45 percent were reported to be implemented for deontic reasons (e.g., managers stated that they thought it was the right thing to do; they wanted the employee to suffer less or explained that they wanted to show respect and justice toward the employee). The next, but less frequently cited, motives—30 percent of the total Robin Hood incidents—were relational concerns (e.g., the managers wanted to foster a satisfying relationship, show recognition, and maintain a good social climate). Finally, 24 percent reported that they were motivated by instrumental reasons (e.g., managers wanted to improve subordinates’ work performance, motivation, and acceptance of the situation and to prevent complaints).

STUDY 2: MANAGERIAL ROBIN HOODISM AS A RESPONSE TO DIFFERENT JUSTICE VIOLATIONS

The objective of study 2 was to test hypothesis 1. We collected data on managerial Robin Hood behaviors from the vantage point of coworkers who may have directly or indirectly learned that such behaviors have occurred. Degoey (Reference Degoey2000) noted that employees demonstrate a natural inclination to talk about injustice observations with others as part of their everyday social interactions. Building on this perspective, and on the folktale that Robin Hood was a legend known far and wide for his deeds, we assumed these events were known among coworkers.

Method

Participants

Data were collected via Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk), an online marketplace for virtual work. MTurk samples are more representative of the general population in terms of demographics and relevant work experiences than participants from traditionally used student subject pools (Behrend, Sharek, Meade, & Wiebe, Reference Behrend, Sharek, Meade and Wiebe2011). Empirical evidence also suggests that MTurk participants exert respectable levels of effort on tasks providing honest and meaningful responses of even superior quality compared to other data collection methods (Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, Reference Buhrmester, Kwang and Gosling2011; Hossain & Kauranen, Reference Hossain and Kauranen2015; Mason & Suri, Reference Mason and Suri2012; Paolacci & Chandler, Reference Paolacci and Chandler2014). In addition, researchers showed that experimental findings were consistent in samples obtained from MTurk (Goodman, Cryder, & Cheema, Reference Goodman, Cryder and Cheema2012).

An invitation to participate was sent to three hundred full-time employees to ensure the participants had recent work experience. We also restricted the participants to residents of North America to enhance uniform data quality (for a discussion, see Goodman et al., Reference Goodman, Cryder and Cheema2012). Fourteen responses were dropped because the individuals were not employed full time, twelve were deleted because they failed to provide responses to the whole survey, and nine failed the quality check (described later), resulting in 265 usable responses. This resulted in 93 percent of our subjects completing the survey to adequate standards. Participants omitted due to not having a full-time job consisted of only 5 percent of observations. Of the usable responses, 58 percent of the respondents were male (SD = .49), their average age was 30.98 years (SD = 9.33), they had an average of 9.31 years (SD = 8.89) of work experience, and the respondents came from a variety of industries, including technology, manufacturing, service, operations, and education.

Procedures

Consistent with our theoretical focus at the incident level, we used a critical incident technique in the survey design. Participants were asked to write about a time when they observed MRH. While we anticipated that justice would predict MRH, we expected that distributive and interpersonal justice would have a stronger relationship than would procedural. Based on our theory and the support given by our preliminary study, we did not include informational justice in our investigation. Participants were randomly assigned to distributive, procedural, or interpersonal injustice conditions. First, all participants were given the definition of MRH that was described earlier and used in our preliminary study 1.

Next, participants were asked to write about a specific incident that occurred at their present or previous workplace in which they observed or became aware of a manager who demonstrated Robin Hood behaviors. In the distributive justice condition, participants were asked to recollect a situation when an employee received an unfair outcome and a supervisor or manager acted as a Robin Hood. In the procedural justice condition, participants were asked to recall a situation when an employee was the victim of an unfair procedure or decision-making process and a supervisor or manager acted as a Robin Hood. In the interpersonal justice condition, participants were asked to think about a situation when an employee was treated interpersonally unfairly by a senior executive and a supervisor or manager acted as a Robin Hood. To increase the likelihood of variance in the predictor variables, and be consistent with previous studies exploring justice-related behaviors with lesser versus greater severity (Jones, Reference Jones1991), we instructed half the respondents on a randomly assigned basis to recall an incident that was less severe and the other half to recall an incident that was more severe.

Measures

Once they finished writing about their respective justice violations, they completed a series of questions. We included three items as intention checks (Behrend et al., Reference Behrend, Sharek, Meade and Wiebe2011; Cheung, Burns, Sinclair, & Sliter, Reference Cheung, Burns, Sinclair and Sliter2017; Meade & Craig, Reference Meade and Craig2012), which were distributed throughout the survey. As a preliminary measure of our dependent variable, the five Robin Hood behaviors reported in study 1 (see Figure 1) were rewritten into a behavioral scale. Participants responded to the following items: “Please indicate the degree to which your supervisor (a) provided a small gift; (b) allocated a small bonus or alternative compensation, (c) provided some alternative informal form of compensation, (d) gave some small favor, and (e) provided some fringe benefit to the mistreatment victim.” Responses were given using a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The items were averaged to form the measure; higher scores signified higher levels of Robin Hood behaviors. To check whether the participants responded to the more versus less severe justice violations as intended, we asked them to respond to a single item: “Please rate the seriousness of this event.” They responded on a 10-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (minor) to 10 (major). As is explained subsequently, this measure was also used to test for the possibility of unfair comparisons of the predictor variable (Cooper & Richardson, Reference Cooper and Richardson1986).

Results and Discussion

Two research assistants independently coded the participants’ written descriptions in terms of whether the content described a distributive, procedural, or interpersonal justice violation. The data were coded as whether the respective justice dimension was present (1) or absent (0). Interrater agreement was .92, which exceeded the Cohen’s (Reference Cohen1960) threshold of .75 and suggested an excellent agreement (Fleiss, Reference Fleiss1981). The coding results reveal that the majority of participants provided the correct justice violation descriptions in the distributive (82.3 percent), procedural (78.3 percent), and interpersonal injustice (86.7 percent) conditions. Because we were interested in specific and distinct justice dimensions, incidents that contained one and only one justice dimension in their descriptions were used in our analyses. This was important to ensure that we were focusing on a singular and specific justice dimension as opposed to multiple dimensions. For construct clarity purposes, we also wanted to ensure that their incidents were consistent with the definitions provided by the literature. Forty-eight incidents were dropped because they contained more than one justice dimension, and nineteen incidents were dropped because the participant incorrectly classified the justice dimension. The final number of justice incidents used in the analyses was 198.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) results showed that, across conditions, the participants rated the severity manipulation check higher in the more (M = 7.31; SD = 2.60) as compared to the less serious (M = 3.90; SD = 1.57) violation condition, F(1, 197) = 122.44, p < .001, η p 2 = .38. This result indicated that the severity manipulations were effective. ANOVA results also showed that the seriousness of the transgression was not significantly different across the three justice dimensions for the low, F(1, 94) = 1.09, p = .33, and high, F(1, 102) = .71, p = .51, justice conditions, providing evidence that severity did not vary among the three justice dimensions (Cooper & Richardson, Reference Cooper and Richardson1986). To assess the psychometric quality of the MRH measure, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis of the five items. The results showed that all items loaded on one factor, explaining over 64 percent of the variance in the measure, with factor loadings ranging from .753 to .832. Scale reliability was assessed with Cronbach’s alpha (α = .86).

To test hypothesis 1, we conducted an ANOVA with the MRH as the criterion variable and justice type and severity as predictors. The results showed that the main effects of justice type, F(2, 192) = 2.62, p < .05, and severity, F(1, 192) = 19.09, p < .05, predicting MRH were significant, as was the interaction term, F(2, 192) = 3.34, p < .05. The significant interaction term indicates that some dimensions are more predictive than others. We followed up with three separate ANOVAs, one for each justice dimension, with severity as the predictor variable and MRH as the criterion. The results were significant for distributive, F(1, 69) = 13.48, p < .001, and interpersonal justice, F(1, 65) = 11.28, p < .001, but not for procedural justice, F(1, 58) = .17, p = .67. Table 1 provides the sample sizes, means, standard deviations, and means differences for the MHR measure for each condition. These findings support our first hypothesis.

Table 1: Managerial Robin Hood Behavior as a Function of Severity and Justice Violation (Study 2)

Note. Means with similar subscripts are not significantly different from each other.

STUDY 3: MORAL IDENTITY AND MANAGERIAL ROBIN HOODISM

The goal of study 3 was to test hypothesis 2. Hypothesis 2 recognizes that some people see moral concerns as highly central to their self-identity (high moral identity), others less so (low moral identity). As those with strong moral identities are especially reactive to moral violations, and as interpersonal justice tends to have salient moral implications, managers with high moral identities should manifest MRH when interpersonal justice is violated regardless of the level of distributive justice. However, the same should not be true for those with low moral identities. These individuals are likely to be responsive to other nonmoral aspects of a justice violation. Consequently, they should show similar and additive responses to both interactional and distributive justice violations.

Method

Participants

We sampled 187 managers enrolled in an MBA program in France. Participation was on a voluntary basis. Only three participants declined involvement in the study, bringing the final total to 184. The average participant age was 29.86 (SD = 4.01) years, and they had an average of 5.8 years of managerial experience (SD = 4.9). Of the sample, 33 percent were female and 67 percent were male.

Procedure

This study consisted of a 2 (low vs. high distributive justice) × 2 (low vs. high interpersonal justice) between-subjects factorial design with subjects randomly assigned to conditions. Participants read a scenario in which we manipulated a distributive and interpersonal justice violation experienced by an employee, whose name was Marc. In the high distributive justice condition, Marc did not receive a favorable outcome because his qualifications, experience, performance, and contribution were lower compared to the other employee who received the favorable outcome. In the low distributive justice condition, Marc did not receive the favorable outcome he expected even though his qualifications, experience, performance, and contribution were superior to the other employee who received the favorable outcome (see scenarios in the appendix). In the high interpersonal justice condition, the president of the company expressed to Marc that he regretted the unfavorable decision, saying that he was sorry and that he respected Marc’s contribution to the company. In the low interpersonal justice condition, the president expressed to Marc a lack of concern for the unfavorable decision and spoke in a rude and discourteous manner.

Participants were asked to assume the role of Marc’s immediate supervisor. To provide participants with a variety of situations in which an employee might be mistreated, we randomly assigned participants to read one of three different scenarios: Marc was not selected as a team leader for a major project (scenario 1) (n = 66), Marc was denied a promotion (scenario 2) (n = 60), or Marc did not receive a bonus (scenario 3) (n = 61).

We measured moral identity using Aquino and Reed’s (Reference Aquino and Reed2002) internalization scale. When moral identity is strongly internalized, it is of central importance to one’s self-concept. For this measure, the participants were asked about the importance of nine moral traits (caring, compassionate, fair, friendly, generous, helpful, hardworking, honest, and kind). Sample items are “It would make me feel good to be a person who has these characteristics” and “Being someone who has these characteristics is an important part of who I am.” The five items measuring internalization were answered on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree) (α = .81).

The manipulation check for distributive justice consisted of one item that reflected Adams’s (Reference Adams and Berkowitz1965) equity theory: “Compared to his coworker(s) in the scenario, Marc was more qualified (1), equal to (2), or less qualified (3) than his coworker(s).” Since participants knew that Marc did not receive the outcome he had expected, higher numbers signified that this was understandable due to his lack of qualifications and thus meant greater distributive justice. The manipulation check for interpersonal justice consisted of one item: “The President treated Marc with sensitivity and respect.” Participants responded using a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

To measure MRH, we used the five items derived from our first study. These items indicate actions that a manager might take to assist an employee who had been wronged in the manager’s mind. These items are “Please indicate the degree to which you as Marc’s supervisor would provide a small gift to Marc,” “… allocate a small bonus or alternative compensation for Marc,” “… provide some alternative informal form of compensation for Marc,” “… give Marc a small bonus budget,” and “… provide some fringe benefits to make up for Marc’s loss.” Responses ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) on a 5-point Likert-type scale. The items were averaged to form the measure such that higher (vs. lower) numbers signified higher likelihood of compensation (α = .83). Besides being reported by our study 1 informants, these items have an added advantage: these actions benefit the putatively wrong employee (positive deviance) without being deleterious to upper management (negative deviance). Thus they allowed for a cleaner test of our hypothesis. We controlled for age and gender because these variables have been shown to be related to moral identity (Reed & Aquino, Reference Reed and Aquino2003). Both variables were self-reported, with gender coded 0 and 1 for females and males, respectively.

Results and Discussion

We first tested whether participants’ responses differed across the three different scenarios (i.e., selection decision to be a team leader, promotion decision, and pay decision). We dummy coded the scenarios into three groups (1, 2, and 3) and conducted a series of ANOVAs with group as the independent variable and our measured variables as the dependent variables. The results revealed no differences with regard to any of the measured variables: moral identity, F 2,182 = .62, p = .71; gender, F 2,182 = .01, p = .81; age, F 2,182 = 1.05, p = .33; and MRH, F 2,182 = 1.01, p = .31. Thus we aggregated the data into one group and conducted the analysis on the entire sample.

Next, we tested whether our manipulations were effective. We used a full factorial MANOVA to assess the effectiveness of the manipulations and to determine whether there was spillover between our manipulations of interpersonal and distributive justice (Perdue & Summers, Reference Perdue and Summers1986). Spillover is common in empirical research simultaneously manipulating multiple justice types (e.g., Zapata-Phelan, Colquitt, Scott, & Livingston, Reference Zapata-Phelan, Colquitt, Scott and Livingston2009). The results revealed a main effect of the distributive justice condition on its manipulation check in the desired direction, F 1,183 = 52.78, p < .001 (M = 2.35 vs. 1.78, η p 2 = .18). A main effect was also observed between the interpersonal justice condition and its manipulation check in the desired direction, F 1,183 = 98.49, p < .001 (M = 3.55 vs. 1.78, η p 2 = .30). No spillover effects were observed for the distributive justice manipulation on the interpersonal justice manipulation check, F 1,183 = .44, p = .50, or the interpersonal justice manipulation on the distributive justice manipulation check, F 1,183 = 1.67, p = .19. The means, standard deviations, and correlations are given in Table 2.

Table 2: Summary of Intercorrelations, Means, and Standard Deviations for Study 3

Note. N = 184. Distributive and interpersonal justice are coded low (0) and high (1). Gender is coded female (0) and male (1). Where relevant, reliabilities are given in parentheses along the diagonal.

*p < 0.05. **p < 0.01.

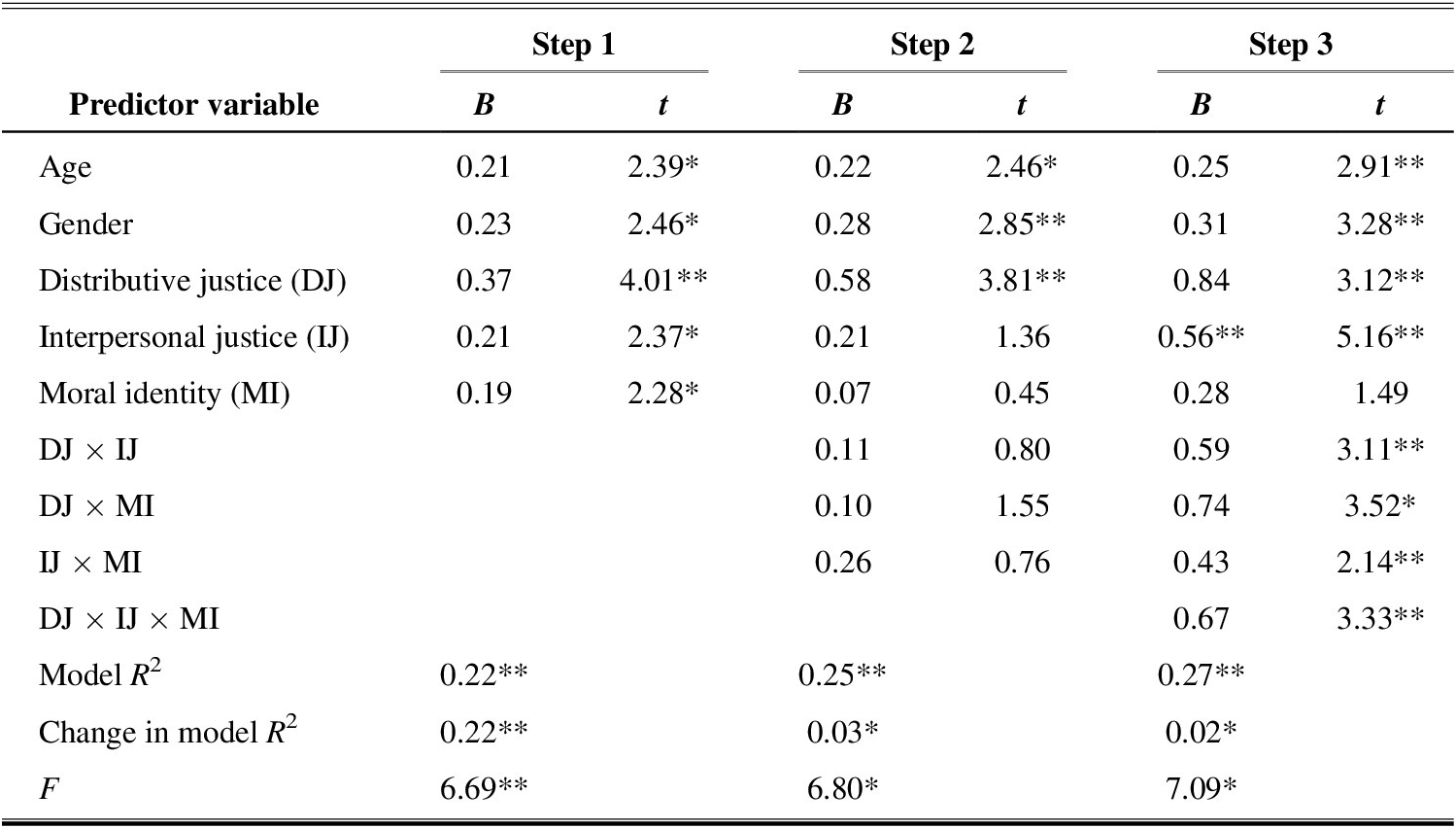

Hypothesis 2 states that a three-way interaction among distributive justice, interpersonal justice, and moral identity predicts MRH. Following Aiken and West (Reference Aiken and West1991), we centered moral identity. We then created two- and three-way interaction terms among the predictors. We used hierarchical regression to test for a significant three-way interaction. We entered age, gender, and the main effects in step 1 and the two-way and the three-way interaction in steps 2 and 3, respectively. As Table 3 shows, the three-way interaction among distributive justice, interpersonal justice, and moral identity was significant (β = 1.67, p < .05). Similar results were observed not controlling for age and gender.

Table 3: Hierarchical Regression Results Predicting Managers’ Tendency to Demonstrate Managerial Robin Hoodism (Study 3)

Note. N = 184. Distributive and interpersonal justice are coded (0) low and (1) high. Moral identity is coded neutral prime (0) and moral identity prime (1). Gender is coded female (0) and male (1).

*p < 0.05. **p < .01.

To examine the shape of the interaction, we divided the sample into low and high moral identity based on one standard deviation above and below the mean. For managers low on moral identity, the two-way interaction term between distributive and interpersonal justice was not significant (β = .09, p = .65). As predicted, both types of justice violations predicted MRH (two main effects): at low levels of moral identity, MRH increased as either distributive or interpersonal justice decreased from high to low. In contrast, among high moral identity managers, a different pattern emerged. A significant two-way interaction between distributive and interpersonal justice was observed (β = .42, p < .05). As shown in Figure 2, when interpersonal justice was low, managers tended to engage in high levels of MRH at both low and high levels of distributive justice, supporting hypothesis 2. However, a closer inspection of the results revealed an unexpected pattern of results for distributive justice. When distributive justice was low, high levels of MRH were observed at both low and high interpersonal justice, suggesting that violation sensitivity similarly occurred for both distributive and interpersonal justice violations.

Figure 2: Managerial Robin Hoodism as a Function of Interpersonal and Distributive Justice at Low and High Levels of Moral Identity (Study 3).

The results of study 3 support our hypothesis that high moral identifiers respond differently to justice violations. However, although we predicted that interpersonal justice violations would be more important than distributive justice violations in predicting MRH, supervisors who have a high moral identity appear to demonstrate a moral duty to compensate the harmed party, and they do so similarly regardless of whether there was one injustice or two. An unexpected finding is that when an employee is unjustly treated—regardless of whether it is a violation of distributive or interpersonal justice (or both)—high moral identity managers engage in MRH by compensating the employee.

STUDY 4: SITUATIONAL CUES AND MANAGERIAL ROBIN HOODISM

In study 4, we sought to further test hypothesis 2 by testing whether similar effects would be observed using a situational prime for moral identity salience. In addition, we modified our methodology. In particular, we had participants describe their behavior in response to an actual event rather than a hypothetical vignette. Similar findings with these two modifications should provide strong evidence for our theory.

Method

Participants

We sampled 123 managers attending MBA classes in a large university located in North America. Participation was on a voluntary basis, and 4 participants failed to provide complete information, reducing the total to 119 participants. The participants’ average age was 28.74 years (SD = 6.20), and they had an average of 4.91 years of work experience (SD = 5.31). Of the sample, 33 percent were female and 67 percent were male.

Procedure

The study consisted of a between-subjects factorial design, with participants randomly assigned to either the moral identity prime or the neutral prime condition. First, we used the critical incident technique (Flanagan, Reference Flanagan1954) and asked the participants to recall and write out a short description of a time when an employee was mistreated by upper management. Second, we administered either the moral identity or the neutral prime manipulation. Following a priming procedure developed by Aquino et al. (Reference Aquino, Freeman, Reed, Lim and Felps2009), in the moral identity condition, we asked the participants to think of the type of person they are and to list five reasons why they might consider themselves to be a moral person. In the neutral condition, we asked the participants to think of a “square” and to list five reasons why a square is a useful shape. The conditions were coded moral identity prime (1) and neutral prime (0). Third, we asked the participants to put themselves in the shoes of the immediate supervisor of the harmed party in the story they had recalled. Last, they completed a measure of MRH and provided their demographic information.

We asked the participants to indicate the extent to which they agreed that the writing exercise made them think about how moral of a person they are. This question was embedded in a list of similar questions (e.g., “how intelligent of a person are you”) to disguise the nature of the manipulation. We used a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree).

Two expert raters, one of the authors and a doctoral student in organizational behavior, independently content coded the participants’ descriptions of the treatment in terms of whether the violation was a distributive or interpersonal justice violation. The interrater agreement was .92. Disagreement was resolved by discussion and consensus. To measure MRH, we used the same five items that were employed in studies 2 and 3 (α = .82). Consistent with study 3, we again controlled for age and gender. Both variables were self-reported, with gender coded 0 and 1 for females and males, respectively.

Results and Discussion

The results indicated that the moral identity manipulation was effective. Participants in the moral identity prime condition reported that the writing exercise made them think about how moral of a person they were (M = 5.60, SD = 1.19) more than those in the neutral condition (M = 2.03, SD = 1.77), F(1, 117) = 164.69, p < .001, η p 2 = .58. In addition, the coding for justice violations showed that a distributive justice violation was provided by eighty-one (67.9 percent) of the participants and that an interpersonal justice violation was reported by sixty-two (52.1 percent) of the participants. The means, standard deviations, and correlations are given in Table 4.

Table 4: Summary of Intercorrelations, Means, and Standard Deviations (Study 4)

Note. N = 119. Distributive and interpersonal justice are coded low (0) and high (1). Moral identity is coded neutral prime (0) and moral identity prime (1). Gender is coded female (0) and male (1). Where relevant, reliabilities are given in parentheses along the diagonal.

*p < 0.05. p < 0.01.

We again used a hierarchical regression analysis to test hypothesis 2. As shown in Table 5, the three-way interaction among distributive justice, interpersonal justice, and moral identity prime was significant (β = .67, p < .01). To probe the interaction, we regressed MRH on the controls, the main effects, and two-way interactions between distributive and interpersonal justice for participants in the moral prime versus neutral prime condition. As demonstrated in Figure 3, among participants in the neutral prime condition, the two-way interaction between distributive and interpersonal justice was not significant (β = .27, p = .25). MRH increased when either form of justice decreased from high to low (two main effects). In contrast, among participants in the moral identity prime condition, the two-way interaction between distributive justice and MRH was significant (β = .58, p < .01). MRH was at its lowest when both distributive and interpersonal justice were high. However, in conditions when interpersonal justice was low, MRH was high no matter the level of distributive justice. As in study 3, however, among high moral identifiers, MRH was highest when either distributive or interpersonal justice was high. As a similar three-way interaction is observed in studies 3 and 4 using different approaches to moral identity—an individual difference approach and a situational prime—we have greater confidence in our findings.

Table 5: Hierarchical Regression Results Predicting Managers’ Tendency to Demonstrate Managerial Robin Hoodism for Study 4

Note. N = 119. Moral identity is coded neutral prime (0) and moral identity prime (1). Gender is coded female (0) and male (1).

*p < 0.05. **p < 0.01.

Figure 3: Managerial Robin Hoodism as a Function of Interpersonal and Distributive Justice for Neutral Prime and Moral Identity Prime Conditions (Study 4).

The coding process also revealed that both forms of justice were reported as violated by twenty-four (20.1 percent) of the participants, indicating spillover between the two forms of justice. In terms of spillover, as we asked participants to recall real-life incidents, it is likely that more than only one form of justice violation could emerge. To correct for spillover, we used a technique outlined by Perdue and Summers (Reference Perdue and Summers1986) and applied in previous research (Colquitt, Scott, Judge, & Shaw, Reference Colquitt, Scott, Judge and Shaw2006; Zapata-Phelan et al., Reference Zapata-Phelan, Colquitt, Scott and Livingston2009). Specifically, we controlled for the shared variance between two justice dimensions by regressing one dimension onto the other, using the unstandardized residuals as our measures of distributive and interpersonal justice in our regression analysis. Doing so provided a cleaner test of our hypothesis.

The results from study 3 also supported hypothesis 2, suggesting that MRH is indeed a moral response to a justice violation. Among high moral identifiers, low levels of interpersonal injustice triggered MRH at both low and high levels of distributive justice, reflecting as predicted a high sensitivity to interpersonal justice violations. As in study 3, however, an unexpected result was that high moral identifiers also demonstrated a high sensitivity to low distributive justice and that high levels of MRH were triggered when one or both forms of justice were low. When managers were low on moral identity, they behaved differently, compensating each type of justice in roughly the same (additive) way.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

In four studies, we explored a specific but important third-party justice situation in organizations, namely, what happens when supervisors perceive their subordinates have been treated unfairly by senior executives. We found that outcome-oriented justice violations tend to lend themselves to MRH, regardless of whether the outcome in question is economic (distributive) or socioemotional (interpersonal). In studies 3 and 4, when moral identity was high, interpersonal justice predicted high levels of MRH whether distributive justice was low or high. However, there was a second (and unexpected) interaction, namely, that high distributive injustice seemed to have much of the same effects on high moral identifiers as high interpersonal injustice. When moral identity was low, then interpersonal and distributive justice were related to MRH to about the same degree (two main effects).

Contributions and Theoretical Implications

At the most fundamental level, our four studies provide a definition and description of a new construct, MRH. Managers freely admitted to allocating organizational resources to employees, doing so after the worker experienced (what the manager judged to be) unjust treatment (study 1). Observers also reported seeing this sort of behavior (study 2). One might find it surprising that representatives of the organization acknowledged breaking rules so openly. In study 1, managers saw themselves as engaging in wrongful conduct, but for “good reasons.” This, in addition to the confidentiality that was guaranteed to them, may have helped them talk to us about this rule-breaking behavior. As agents of fairness, they felt that their actions were justified.

A close look at our measure tells us something else about MRH. At one level, managers could choose one action but not another. By this reckoning, the behaviors would be “either–or” rather than “but–and.” However, this did not seem to be the case. Our study 2 factor analysis, as well as the sizable coefficient alphas, suggests that the behavioral items in the MRH measure held together well. Supervisors who were likely to do one Robin Hood behavior were likely to do others. This suggests that MRH is similar to related constructs, such as positive or constructive deviance (e.g., Spreitzer & Sonenshein, Reference Spreitzer and Sonenshein2004; Warren, Reference Warren2003). Specifically, MRH is part of a family of compensatory behaviors, which some supervisors use when a subordinate is unfairly treated. This is an important finding, as it provides a measurement basis for future investigations.

A second contribution of our work involves identifying the motives underlying MRH. Managers have practical concerns and will sometimes use organizational resources to achieve them. However, our data show that moral motives are also important. Our supportive results provide additional evidence for Folger and Salvador’s (Reference Folger and Salvador2008) theory of deontic justice. When individuals go to work, they are economic actors. However, they are not only economic actors, as they bring their ethical beliefs with them (Cropanzano et al., Reference Cropanzano, Goldman and Folger2003). Beyond this finding, we extend deontic justice research, demonstrating that third-party responses need not be solely punitive. As suggested by Mitchell et al. (Reference Mitchell, Vogel, Folger, Giacalone and Promislo2012) and Priesmuth et al. (Reference Priesmuth, Mitchell, Folger, Bowling and Hershcovis2017), individuals can also respond by providing assistance to the victim. Future research might consider when each of these responses—punitive or compensatory—is more likely.

A third contribution has to do with the structure of organizational justice. While some work has found it useful to think in terms of “overall” or “composite” justice (Ambrose, Wo, & Griffith, Reference Ambrose, Wo, Griffith, Cropanzano and Ambrose2015), our results inject a note of caution. The various types of justice are not identical. Some are more outcome oriented, as Greenberg (Reference Greenberg and Cropanzano1993) noted, whereas others may have more obvious moral relevance (Folger, Reference Folger, Gilliland, Steiner and Skarlicki2001; Scott et al., Reference Scott, Colquitt and Paddock2009). Given these differences, any aggregation of justice types could lead to the loss of some information. For some applications, this will not pose a theoretical concern. For others, such as the study of MRH, an overall justice construct would mask genuine differences among the justice types (for a more detailed treatment of these issues, see Colquitt & Rodell, Reference Colquitt, Rodell, Cropanzano and Ambrose2015). On the basis of our findings here, we would encourage researchers to look beyond factor solutions and consider the correlates of the different types of justice. For example, interpersonal and distributive justice were related to MRH, whereas procedural justice was a less efficacious predictor.

While our findings generally support the use of separate justice dimensions, we highlight informational justice as a potential exception. While the nonmention of informational justice in study 1 was consistent with our theory, we were still somewhat surprised that no one reported MRH to resolve an informational violation. This could reflect a problem with informational justice as a separate construct. Historically, the conceptual status of informational justice has been unclear. Originally, it was considered an attribute of interactional justice (Bies, Reference Bies2001). Later, based on the thinking of Greenberg (Reference Greenberg and Cropanzano1993), informational justice was treated as a separate dimension (Colquitt, Reference Colquitt2001), though not by everyone (Colquitt & Rodell, Reference Colquitt, Rodell, Cropanzano and Ambrose2015). Moreover, findings have been less than consistent. Some factor analytic research has found that informational justice may load with procedural justice (Fortin, Cropanzano, Cugueró-Escofet, Nadisic, & Van Wagoner, Reference Fortin, Cropanzano, Cugueró-Escofet, Nadisic and Van Wagoner2020; Roch & Shanock, Reference Roch and Shanock2006). It might be that informational justice has an uncertain status as a separate “type” of justice. Future research should explore whether informational justice is necessary, beyond procedural and interactional justice.

Our findings also have implications for moral identity. As noted earlier, people who have a strong moral identity or for whom their moral identity is salient by situational cues tend to see their ethical beliefs as central to who they are as individuals (Aquino & Reed, Reference Aquino and Reed2002; Aquino et al., Reference Aquino, Reed, Stewart, Shapiro, Gilliland, Steiner, Skarlicki and van den Bos2005; O’Reilly et al., Reference O’Reilly, Aquino and Skarlicki2016). Thus they tend to interpret ambiguous situations in moral terms (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Aquino and Freeman2008). This effect appears to have been at work in our studies 3 and 4. Those with a strong moral identity engage in MRH when an interpersonal justice violation occurs. However, the reverse is also true. Specifically, our second hypothesis anticipated that the moral prime would similarly enhance the concern for interpersonal justice, such that it would be important regardless of whether there was distributive justice. While this is indeed the case, moral identity—whether as an individual difference or as a moral prime—appears to have increased concern for distributive justice as well (see Figures 2 and 3). Consequently, neither interpersonal nor distributive justice serves as a substitute for the other. Both are important.

We speculate that this substitutability could result from the nature of MRH. When exhibiting these compensatory actions, the third party, including but not limited to a manager, is providing assistance to someone who has been harmed. The Robin Hood does not need to punish a wrongdoer. While moral blame may be more ambiguous for distributive than for interpersonal justice (Folger, Reference Folger, Gilliland, Steiner and Skarlicki2001; Scott et al., Reference Scott, Colquitt and Paddock2009), this attributability may matter less when providing assistance. Even if it is difficult to state who precisely is to “blame” for an undeservedly negative outcome, the victim can still deserve help. And if the manager is mistaken about the injustice, the only harm is that a worker has received an extra benefit. However, when engaging in punishment, as was the context with Turillo et al. (Reference Turillo, Folger, Lavelle, Umphress and Gee2002), moral clarity may be more important. A mistake could cause an innocent person to be wrongly accused and punished. Consequently, it may be that justice judgments are cautious in punishment settings but are more liberal in compensation settings. This would be an important topic for future investigations.

Finally, our findings also have implications for how managers conceptualize their ethical responsibilities. We have emphasized that at least some of these managerial Robin Hoods believe that they are acting ethically. Consequently, they believe that they are doing the right thing. From a moral and practical point of view, this is a debatable point. The manager may trust that an injustice occurred, but this would likely not have been fully adjudicated. A manager might jump to conclusions and cost the organization for an innocent misunderstanding. Vigilante justice has another problem in that it lacks accountability. The amount or type of compensation could be inappropriate or lack proportionality, and those who complain loudest to their manager may be the ones being compensated the most. There are few checks on a supervisor’s judgments.

Finally, we have a deeper concern. At the level of the social system, MRH may be systemically unfair. This is because victim compensation depends on the opinion of the boss and not on an equitable set of rules. Some managers may be more generous (with their employer’s resources), whereas others may be less so. This creates a distributive injustice across different managers. A philosophical analysis of MRH lies beyond the boundaries of this article. However, we emphasize that these issues are not simple or obvious. As this phenomenon becomes better understood, we look forward to the insights of ethicists.

Future Research

MRH is a new construct, and we do not yet know much about it. Future investigations should provide a more complete process model than the one presented here. In addition, we know little about the antecedents and consequences of MRH. In this section, we explore some specific possibilities that the present work suggests.

MRH is an unusual phenomenon because a representative of the organization is engaging in deviant behavior for supposedly “good” reasons. This raises interesting questions regarding its antecedents. Managers who engage in MRH might be poorly socialized employees who are low on conscientiousness and uncommitted to their firms’ mission. Alternatively, they might be deeply sincere individuals who wish others well and want to address a potential harm in the most direct way possible. Our present studies cannot answer this question but may provide some direction for future inquiry. Our guess is that instrumentally motivated managers tend toward the former type, whereas morally motivated managers tend toward the latter. As found here, people engaged in MRH for different reasons. There could be a constellation of negative predictors for one class of individuals and a constellation of positive predictors for the other. Another answer to this question may involve where (or toward whom) a manager feels responsible. A supervisor could be committed to her work team, to her organization, or to both. Perhaps there are distinct profiles with distinct consequences. A supervisor who is committed to her work team but not to her organization might be most likely to exhibit MRH. A supervisor who is committed to her organization but not to her work team might be least likely. At present, these ideas are only speculative but would merit investigating.

While we have emphasized injustice as a cause of MRH, this explanation may not be complete. While injustice certainly encourages people to help others (Skarlicki et al., Reference Skarlicki, Ellard and Kelln1998; Skarlicki et al., Reference Skarlicki, O’Reilly, Kulik, Cropanzano and Ambrose2015), empathy is also a potent motive (Blader & Tyler, Reference Blader, Tyler, Ross and Miller2001). Interestingly, justice and empathy do not always lead to the same outcomes. When decision makers empathize with victims, they may provide the wronged individuals with benefits that outweigh rules of justice (Blader & Rothman, Reference Blader and Rothman2014). In the case of MRH, for example, a manager could give a wronged employee so many resources that it becomes unfair to other workers, to say nothing of how this might affect the organization as a whole. The character of MRH suggests that empathy may sometimes be involved. We encourage investigations into this possibility, particularly as this motive differs from justice concerns.

Perhaps the greatest and most important research challenge will be exploring the consequences of MRH. In our studies, we found that some managers believe that there are benefits to compensating an employee for a perceived injustice. However, the accuracy of this belief is an open question and could best be answered with multilevel research. While we can only speculate, it seems possible that the effects of MRH are not isomorphic across levels of analysis. MRH might be beneficial at the team level but harmful at the organizational level. For example, it is conceivable that MRH might raise trust within work teams. This could potentially boost performance. However, MRH tends not to address the underlying conditions that produced the unfair acts. Consequently, the within-team trust could be purchased at the cost of organizational commitment. These cross-level effects would warrant future research.

Practical Implications

Given that perceived injustices are common in organizations, we suspect that MRH is almost inevitable. Indeed, our studies produced similar results regardless of whether participants were supervisors or subordinates observing their supervisors. MRH appears to be a common phenomenon, perhaps because supervisors have a number of good reasons for compensating wronged subordinates. In the absence of social pressure to do otherwise, they are likely to continue. However, as we have also seen, organizations are likely to be ill disposed to rule violations that undermine senior leadership’s decisions. What is to be done? While we can only speculate at this point, we suggest that a business could take two general orientations.

First, an organization could attempt to eliminate or at least reduce MRH. This could be done either through a compliance-and-control approach or through a climate-of-trust approach. To take a control approach, a firm might reduce its managers’ budget discretion. It might also monitor them closely and impose sanctions for rule violations. This first approach could be more useful in settings where supervisors are favorable toward workers but antagonistic toward senior management (e.g., in some union shops). This might also be the best solution when supervisors lack experience and knowledge of organizational priorities. In such circumstances, perhaps it is best if they do not make controversial decisions. However, a compliance-and -control approach may have paradoxical consequences. What if more rules motivate managers to engage in more MRH? Of course, if a firm has antagonistic and unqualified supervisors, then MRH might be the least of its problems. A trust approach to reducing MRH would tend to increase psychological safety. If managers feel they can discuss perceived injustices with their superiors, they may not need to resort to under-the-radar means that undermine the policies of the organization.

As a second approach, which could be combined with the first, an organization could, alternatively, embrace MRH (within bounds). It might accept that such things occur and trust supervisors to make generally reasonable choices. In the strict sense of our definition, it might not be “Robin Hoodism” at all, because managers would not be breaking the rules. Instead, they would be allowed discretion to solve problems by using their units’ budgets. This can work for smaller and nonrecurrent problems, while for larger or persisting issues, it would be necessary to involve upper management to find solutions. This second approach might be more successful when managers and workers share a common sense of purpose. Managers would also need training and experience, perhaps even general guidelines, to recognize when to act and when to involve upper management in their compensation efforts. This would become close to what is nowadays called empowerment, which appears to work best in healthy organizations.

Limitations

One area of concern for this research is external validity. In our research, we used four independent samples. Study 1 directly interviewed working managers, and all of our present investigations surveyed individuals who had work experience. Nevertheless, the primary emphasis of studies 3 and 4 was on construct and internal validity. Although we made progress in this regard, additional field studies would be helpful in establishing the generalizability of our findings. Also, rather than being a fully developed scale, our measure of MRH was provided as a preliminary measure that needs further development and validation.

We emphasized two types of justice, distributive and interpersonal, which were found to be important in both studies 1 and 2. According to our theorizing, distributive justice pertains to economic outcomes, and interpersonal justice pertains to socioemotional outcomes. Intriguingly, our findings suggest that when moral identity is low, these two types of justice substitute for one another, at least in the mind of the manager. However, when moral identity is high, each type of justice matters beyond the level of the other. Future investigations should also take a closer look at procedural and informational justice. These do not seem to be resolved via MRH (see studies 1 and 2), perhaps because the managers can directly supply missing information, including explaining an unfortunate process.

CONCLUSION

This research extends the deontic perspective of justice in considering how managers as third parties can take steps to compensate a victim deemed to have experienced mistreatment. Our results indicate that MRH can be triggered by perceptions that the subordinate has been treated with a lack of dignity and respect by upper management or has received an outcome that is low in fairness. These effects appear to occur especially among managers whose moral concerns are salient because of interpersonal differences or situational cues.

Acknowledgments

This article is partly based on Thierry Nadisic’s dissertation “The Fair Hand of Managers: How Do Managers Correct Injustice in the Workplace?” defended in 2008 at HEC Paris Business School, France.

APPENDIX

Scenarios for Study 3

Scenario 1: Team Lead Decision—Interpersonal and Distributive Justice Manipulation

You are the manager of an engineering team in TECHNOSURE, a medium-sized firm that provides tailor-made IT solutions to a range of companies. Marc, who is one of your subordinates, has been working over the last twelve months preparing a new project. Marc would love to launch this project now.

To his surprise, Marc learned from one of his colleagues, who knew it from the President, that someone else had been chosen as the person to launch the project. (Low Interpersonal Justice: When Marc met with the President, the President told him rather harshly that he would give him only a few minutes. The President was verging on being rude and discourteous. High Interpersonal Justice: When Marc met with the President, the President told him that he was happy to give Marc all the feedback he needed. The President said he was really sorry that he could not give Marc this opportunity now, and that the company appreciated his contribution.)

Marc believes, however, that the person chosen to launch the project is considerably (Low Distributive Justice: less/High Distributive Justice: more) qualified and experienced than Marc and has (Low Distributive Justice: poorer/High Distributive Justice: better) results than Marc.

Scenario 2: Promotion to Team Leader—Interpersonal and Distributive Justice Manipulation