Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 September 2015

Inscriptions on STONE have been arranged as in the order followed by R.G. Collingwood and R.P. Wright in The Roman Inscriptions of Britain Vol. i (Oxford, 1965) and (slightly modified) by R.S.O. Tomlin, R.P. Wright and M.W.C. Hassall, in The Roman Inscriptions of Britain Vol. iii (Oxford, 2009), which are henceforth cited respectively as RIB (1–2400) and RIB III (3001–3550). Citation is by item and not page number. Inscriptions on PERSONAL BELONGINGS and the like (instrumentum domesticum) have been arranged alphabetically by site under their counties. For each site they have been ordered as in RIB, pp. xiii–xiv. The items of instrumentum domesticum published in the eight fascicules of RIB II (Gloucester and Stroud, 1990–95), edited by S.S. Frere and R.S.O. Tomlin, are cited by fascicule, by the number of their category (RIB 2401–2505) and by their sub-number within it (e.g. RIB II.2, 2415.53). When measurements are quoted, the width precedes the height.

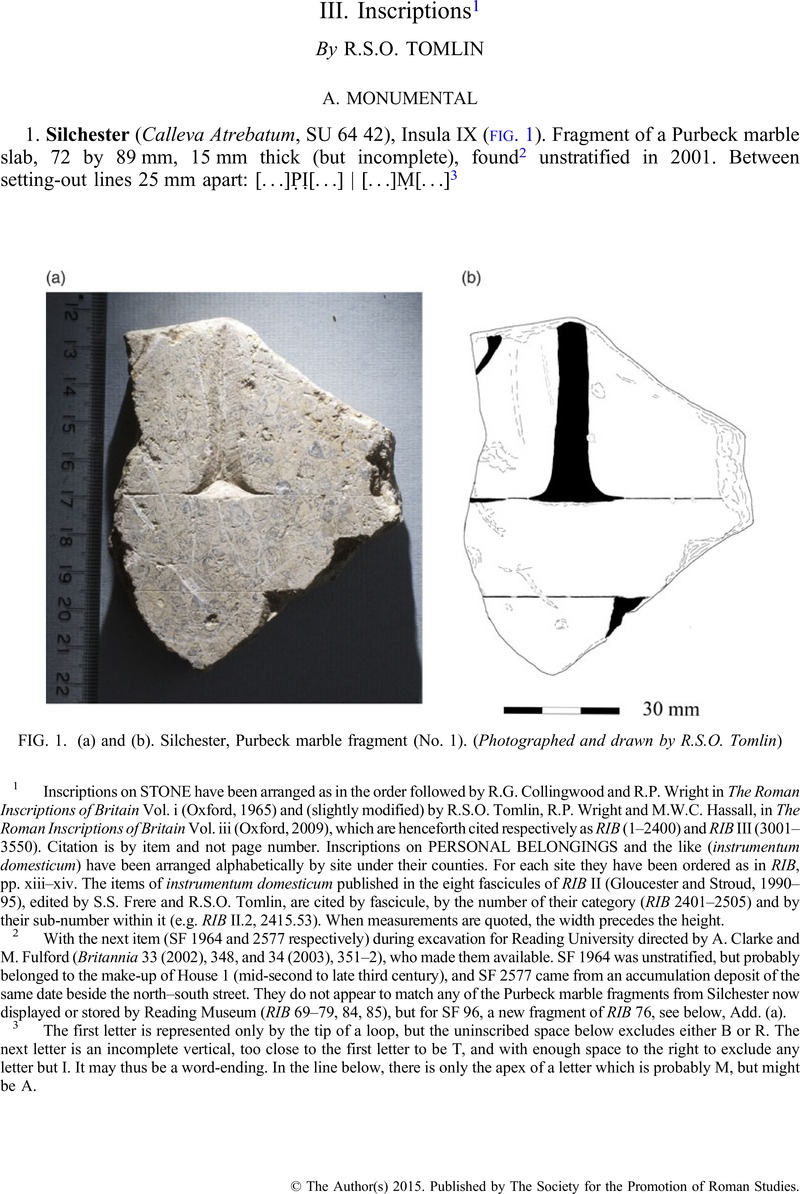

2 With the next item (SF 1964 and 2577 respectively) during excavation for Reading University directed by Clarke, A. and Fulford, M. (Britannia 33 (2002), 348, and 34 (2003), 351–2)CrossRefGoogle Scholar, who made them available. SF 1964 was unstratified, but probably belonged to the make-up of House 1 (mid-second to late third century), and SF 2577 came from an accumulation deposit of the same date beside the north–south street. They do not appear to match any of the Purbeck marble fragments from Silchester now displayed or stored by Reading Museum (RIB 69–79, 84, 85), but for SF 96, a new fragment of RIB 76, see below, Add. (a).

3 The first letter is represented only by the tip of a loop, but the uninscribed space below excludes either B or R. The next letter is an incomplete vertical, too close to the first letter to be T, and with enough space to the right to exclude any letter but I. It may thus be a word-ending. In the line below, there is only the apex of a letter which is probably M, but might be A.

4 P is 72 mm high. From the foot of the loop, a faint line continues to the right, as if to begin the second loop of B, but there is no incision at the foot. In the broken edge to the right, is part of a bottom-serif and the beginning of a vertical stroke, too steep for A, but presumably E, I, L or R. In the broken edge below P, there is the edge of a horizontal stroke, E, F or T.

5 During excavation of the Three Bridges Garage site for St James’ Place and Citygrove by Cotswold Archaeology, directed by Cliff Bateman and Neil Holbrook, who made the stone available and provided details. It was also examined by Martin Henig and Grahame Soffe. Although it was found just after 2014, it is included here because of its importance and the interest it immediately aroused; see, for example, Adcock, Kate, ‘From the Isles of the Blessed to the Empty Tomb – the newly discovered Roman tombstone from Cirencester’, ARA News 33 (March 2015), 4–8Google Scholar.

6 This burial is of a man. The back and sides of the stone are unworked, which suggests that it was not intended to be free-standing, but to be inserted into a masonry structure such as a mausoleum or the rectangular enclosure found c. 30 m away, assuming this to be funerary. Its original location, as well as its re-use face-down, may have protected it from weathering.

7 The lettering, which appears to be influenced by a previous brush-drawn text (notably in the sinuous serifs and the treatment of A, M and N), is incongruously inferior in drawing, layout and execution to the sculptured decoration. Letter-heights: 1, 42 mm; 2, 53 mm; 3, 52 mm; 4, 50 mm; 5, 53 mm; 6, 50 mm. It was ordered by means of seven pairs of setting-out lines above a single line, but only five of the seven bands thus formed were actually used, and the very first letter was inserted in what was evidently meant to be an upper border 42 mm wide between the top edge of the panel and the first pair of setting-out lines. These oversights may suggest that some text was accidentally omitted, but they are more likely due to miscalculation and the disregard of layout seen in the asymmetry of D M and the division of ANNO | S.

The very first letter is I, formed like the first I in BODICACIA and XXVII, and thus not an unfinished D. The best suggestion is that the heading was meant to be D(is) I(nferis) M(anibus), but D I M is difficult to deduce from an off-centre D M with a diminutive I above the M. Although this formula is widespread, it has occurred only once in Britain, far away in Papcastle (RIB III, 3221). Bodicacia, the subject of vixit, is the name of the deceased. It is previously unattested, but must be derived from Boudica in the alternative form of Bodica (compare ILS 2653, Lollia Bodicca). The termination -acia is difficult, but like some Celtic masculine names in -acus, it might be hypocoristic or patronymic (see further Russell, P., ‘The suffix -ako- in Continental Celtic’, Études Celtiques 25 (1988), 131–73Google Scholar, esp. 136–8). Bodicacia is described as coniunx, but in epitaphs this term is more often applied to the dedicator, the surviving widow or widower, than to the deceased. It points to the puzzling absence of any dedicator, but it is difficult to suppose that the widower's name has been accidentally omitted, since the sense continues with vixit, of which Bodicacia is the subject. There is a parallel in RIB 113, also a gabled tombstone from Cirencester, although it is in the dative case: D(is) M(anibus) Iuliae Castae coniugi vix(it) ann(os) XXXIII, ‘To Julia Casta, spouse, (she) lived 33 years’. This stone is broken, but just enough of the surface remains to show that the text is complete. Perhaps like Bodicacia's stone, it was erected next to the husband's, which would then have made the dedicator explicit; as already noted, the original location of Bodicacia's stone is unknown, but it does not seem to have been free-standing.

8 During excavation by C.N. and G.E. Grantham of a possible Roman temple-site, but first reported by J.S. Dent, ‘Roman religious remains from Elmswell’, in J. Price and P.R. Wilson (eds), Recent Research in Roman Yorkshire: Studies in Honour of Mary Kitson Clark (Mrs Derwas Chitty) (1988), 89–97, at 93–5 with figs 6.3 (drawing) and 6.5 (photo). The reference was communicated by Martin Millett, and further details were provided by John Dent. The fragment was preserved by Eric Grantham and now belongs to his stepson Peter Makey in Great Driffield.

9 The fragment is broken across the O of DIIO, so it is unknown how many more letters there were in the first line, or whether it contained a word which continued into the next line. Of this only the very top survives of the first three letters, which cannot be identified: Dent suggests E, F, II, N or T for the first; C, G or possibly O for the second; H, I or L for the third. Except that the god is male, the dedication is thus unknown. II for E derives from Roman cursive and is an informal usage found in graffiti rather than monumental inscriptions, but Dent notes it is used on other altars: RIB 125, 645, 1303 [doubtful], 1321 [doubtful], 1522, 1528 and 1991, to which III, 3254 can now be added.

10 By workmen who gave them (with Roman pottery) to the late Lucy Hinson, in whose garden at Grinton they were found by the present owner, Philip Lee, who made them available. Local informants could provide no further details of date and provenance. Also found was the squared corner of a slab in the same stone, 0.25 by 0.18 m, which is inscribed with a six-pointed roundel. This motif occurs mostly on altar bolster-ends, but does supplement the ansate panel RIB 852. But it is not necessarily part of the same inscription, since it is somewhat thicker (0.055 m) and its back is more finished.

11 Height: 1, 59 mm (estimated); 2, 61 mm; 3, 60 mm; 4, 59 mm; 5, 60 mm (estimated). The incomplete letter in 1 is a bottom serif; in 2, there is a suggestion of the raked vertical of M in the left broken edge, and traces of a vertical incision in the right edge; in 3, there is a better trace of a vertical incision in the right edge.

12 The fragments are too slight for restoration, given the many variations possible in titulature and abbreviation, but Severus is identified as usual as [P]ER[TINACI], Caracalla as [ANTONI]NO (which confirms the dative), and Geta as [P] SEP[TIMIO GETAE]. Line 2 must have contained Severus’ titles, and it is difficult to see OD as anything but part of ‘Commodus’, especially if it were preceded by M (see previous note); some inscriptions identify Severus as his brother, fratri Commodi, but this fiction has not occurred before in Britain. In line 4, TH (perhaps THI) must be part of Parthicus, whether it was dative and part of Caracalla's titulature, or genitive and part of his fictive descent from Trajan. In view of the space available, the former is more likely, which means that Parthico was also included among Severus’ titles. In line 5, the nomen which Geta shared with his father was not erased, but his cognomen would have been although this erasure is now lost.

13 With the next three items during excavation by Wardell Armstrong Archaeology for Grampus Heritage and Training. Megan Stoakley and Frank Giecco made them available, and provided details. They are now at Cumwhinton but will go to Tullie House, Carlisle.

14 Heights: 1, 52 mm; 2, 48 mm (estimated, but with initial C larger); 3, 34 mm; 4, 30 mm; 5, 30 mm; 6, 24 mm.

15 The width of text lost is determined by the restoration of CVI in line 3, which is almost certain, the alternative quibus being very rare (although quib(us) is used by the Vangiones in RIB 1328: see below); it is supported by the restoration of RTI in line 1, which is also certain, if Mars bore no abbreviated title. He is likely to have been identified as a god in the line above, now lost, either as DEO (enlarged or centred) or as deo s(ancto).

The names of the cohort and the prefect must be restored. There were two milliary part-mounted First Cohorts V[…] in the British garrison, the Vangiones and the Vardulli, but the Vardulli in their many inscriptions make their other titles explicit, fida (often abbreviated) after the numeral, and c(ivium) R(omanorum) after (milliaria). This leaves the Vangiones, who were at Benwell in the reign of Marcus Aurelius (RIB 1328, 1350), and at Risingham in the third century (RIB 1234, etc.). This is the first evidence that they previously garrisoned Papcastle; the lettering is Antonine or earlier. The prefect's name contains the sequence MOE with enough trace of the next letter to exclude S, which would suggest the cognomen Amoenus, although it is mostly borne by freedmen. His title of praefectus may have been written in full, or abbreviated to accommodate a votive formula such as V S L M. That he was a prefect in command of a milliary cohort, not a tribune, should be noted. This anomaly is also found on the cohort's altar at Benwell (RIB 1328), and on an altar of the Vardulli at Castlecary (RIB 2149). It is repeatedly found on altars at Housesteads of the milliary First Cohort of Tungrians (RIB 1578, 1580, 1584, 1585, 1586, 1591) and a tombstone (1619), and on altars of the milliary Second Cohort of Tungrians at Castlesteads (RIB 1981, 1982, 1983) and Birrens (RIB 2094, 2100, 2104, 2108). In the somewhat earlier Vindolanda Strength Report (Tab. Vindol. II, 154), the First Tungrians are likewise commanded by a prefect although they numbered 752 men, much too many for a quingenary cohort. The same anomaly has been detected in the Ninth Batavians at Vindolanda, and A.R. Birley (in ZPE 186 (2013), at 294) accepts Strobel's suggestion that Tungrian and Batavian nobles who had been given the title of praefectus civitatis in their homeland insisted on retaining the title of ‘prefect’ when they commanded national cohorts. This inverted snobbery was evidently shared by two other tribes, the Vangiones and Vardulli, unless it is more plausible to suggest that milliary cohorts divided between two stations were commanded by a prefect at one station but by an acting-commander (praepositus) at the other, although the absent prefect was its formal commander. Thus the Second Tungrians, although ‘commanded’ by a prefect, erected inscriptions at Castlesteads under the direction of a senior centurion (princeps) (RIB 1981, 1982, 1983), and the First Tungrians (commander not stated) erected an altar at Cramond under the direction of a legionary centurion (RIB 2135). Likewise, the Vardulli (milliary, but commanded by a prefect) and the First Tungrians (milliary, but commander not stated) are both attested at Castlecary (RIB 2149 and 2155 respectively), a fort much too small (1.4 hectares) for either unit at milliary strength. This may be the situation foreshadowed by the Vindolanda Strength Report, which records that 337 men were in fact outposted to Coria.

16 NAE would be rather cramped in line 2, and perhaps NE was written for Vacu[n(a)e], but the correct spelling is anticipated by dea[e] in the line above. The first V of line 2 is scored by a diagonal line, but it looks casual since it begins above the letter; a ligatured VX would be difficult. Line 3 is represented only by the apex of the first letter, perhaps A. The Sabine goddess Vacuna is previously unattested in Britain, epigraphic evidence for her cult being confined to Regio IV of Italy. Horace wrote a poem (Ep. I.10) below her ‘crumbling temple’ (post fanum putre Vacunae), which has been identified with Rocca Giovane near Tivoli. This altar was surely dedicated by a person from the area.

17 Since MIX is almost unknown as a name-ending, there must be two numerals here, ‘months’ preceding ‘years’, with something between them. Since the usual sequence is years, months and days, it would seem that two persons are being commemorated, as in RIB 1920 (Birdoswald). For a local example, see Britannia 45 (2014), 432, no. 2Google Scholar (Old Carlisle). The accusative singular ending VM suggests the formulaic titulum posuit (etc.), which is found locally at Maryport and Brougham, and at other northern forts (see RIB III, 3231, with note).

18 The layout and presentation are thus similar to those of the previous item, but the lettering looks as if it is by another hand.

19 Although it is suggested in the note to RIB III, 3232 (Brougham), that AVR C[…]|VINDA should be restored as Aur(elia) C[uno]|vinda, the Celtic name Vinda is well attested. vixit was evidently abbreviated, but without knowing the length of the numeral in the line below, it is not possible to tell whether it was v(ixit) or vix(it). The former is more likely.

20 Information from Alexander Tweedy of ArtAncient, who sent photographs and other details. It has since been sold. The stated provenance would suggest one of the forts between Durham and the Wall where dedications to Vitiris or ‘Veteres’ are known, Chester-le-Street (RIB 1046, 1047, 1048), Lanchester (RIB 1087, 1088) or Ebchester (1103, 1104). But the vagueness of the provenance, and still more the altar's pristine condition and the neatness of its lettering, which are both unparalleled among dedications to this god, and also the omission of medial points from VSLM, raise the question of whether it is genuine. However, there is no altar of which it is an evident pastiche, and the undistinguished lettering, although it is rather square and painstaking, is not definitely un-Roman.

21 The only instance of the exact formulation deo sancto Vitiri is RIB 1455, which this altar does not resemble. The Celtic name Lunaris is uncommon, but there are three instances from Britain, the tombstone RIB 786 (Brougham) and the altars RIB 1521 (Carrawburgh) and JRS 11 (1921), 101–7Google Scholar (Bordeaux, but originating from York). At the beginning of line 4, VL is unexplained. Unless it is an inept reversal of the LV immediately above, whether by an ignorant forger or a careless stonecutter, it may falsely anticipate the V S L M formula which follows. The vendors suggest v(eteranus) l(egionis), but although this abbreviation is found on two tombstones from the middle Danube (ILS 2343 and AE 1989, 632), the legionary reference is explicit in both, to the same legion as it happens. The ‘humble folk’ who made their ‘inexpensive and crudely inscribed’ dedications to this god (to quote Eric Birley in ANRW II, 18.1, 63) almost never specify their rank, and neither the provenance nor the name Lunaris suggests a legionary veteran.

22 During excavation by the Vindolanda Trust directed by Andrew Birley. Robin Birley sent information and a photograph, Barbara Birley made it available.

23 The uncertainties of titulature and abbreviation prevent a full restoration of this dedication by the Fourth Cohort of Gauls to Septimius Severus and his sons Antoninus (Caracalla) and Geta (whose name and title have been erased as usual), which would also have named the governor and the prefect. The governor is likely to have been Alfenus Senecio, who is named in a Vindolanda fragment (RIB III, 3348) which is possibly part of the same inscription. Line 1 evidently began with [IMP CAES]AR[I] or [IMPP CAES]AR[IBVS], followed by the name and titles of Septimius Severus, which continued into line 2. If this began with [SEVERO PI]O, as seems likely, it would have been better balanced in length by the plural [IMPP CAES]AR[IBVS] in the line above. The medial point before ANTONINO indicates that Marco Aurelio was abbreviated to M AVR. The erasure of Geta's name and title extended over lines 4 and 5, with its beginning lost but the end surviving.

24 Recorded (with photographs) on the PAS database, LVPL-70AF92.

25 Not Roman beyond a doubt, but similar in appearance to RIB II.2, 2412, 87, 90 and 91, all from Cheshire.

26 When they were given by Joseph Mayer to Liverpool Museum with the stated provenance of ‘Carlisle’, which is marked on them in ink. They are now in National Museums Liverpool (World Museum), acc. no. M7641, from where the Curator of Classical Antiquities, Georgina Musket, sent a colour photograph and other details.

27 The left margin can be deduced from the space at the beginning of lines 2 and 3. To the right of the vertical stroke at the end of lines 1 and 2 there is trace of the diminutive loop of R, resembling that in line 3. Here CRII[…] is almost certainly Cres[cens] or a derivative, presumably the name of the potter.

28 During excavation by Wardell Armstrong Archaeology for Grampus Heritage and Training. Megan Stoakley sent a photograph and other details.

29 Senec seems to have been written first as SENCE, and then corrected. Since the three names are all cognomina (even if Tertius is occasionally found as a nomen), they must be the names of successive owners. The first is evidently Senecio, since Cato's name follows on from it, and Tertius’ name is curtailed, the awkward placing of the second T showing that it respected Senecionis which was already there.

30 During excavation by Wardell Armstrong Archaeology for Grampus Heritage and Training, in the season after the previous item. Megan Stoakley and Frank Giecco made it available.

31 Of the first letter only the tip survives; of the others, only the upper half. The last is probably D, but might be P or R.

32 With the next item during excavation by Exeter Archaeology directed by P. Pearce for Land Securities Properties Ltd, in contexts <7610> and <4739> respectively. Alex Croom made them available on behalf of Paul Bidwell, who provided details of context which amplified the note in Britannia 38 (2007), 295–6Google Scholar.

33 The Latin nomen Naevius is found on its own as a cognomen in RIB 179 (an imperial freedman), and perhaps in the samian graffito NAE[…] (Britannia 27 (1996), 451, no. 26Google Scholar). But although it is apparently not followed here by a cognomen, on such an early sherd from Exeter it is surely the nomen of a Roman citizen, no doubt a legionary.

34 A is ‘open’ (without cross-bar), P and R very angular, and S a long diagonal stroke. Aprilis is a popular cognomen, and in Britain is borne by one legionary centurion (RIB 1401) and by the heir of another (RIB 675), no doubt a legionary himself; but they are both of later date.

35 Britannia 23 (1992), 289Google Scholar. The grave-goods (for which see heritagegateway.org.uk) are being studied in a Reading University dissertation by John Ford, who noticed the graffiti and sent photographs and other details.

36 The letters MAS are found as owners’ marks on two amphoras (RIB II.6, 2494.148 and 149) and a cooking pot (RIB II.8, 2503.329). They are either a Roman citizen's three names abbreviated to their initials, for example M(arcus) A(ntonius) S(…), or an abbreviated cognomen such as Ma(n)suetus.

37 With the next item during excavation by Oxford Archaeology (Britannia 41 (2010), 396Google Scholar). Edward Biddulph sent photographs and other details.

38 This is the commonest name to be abbreviated to VEN (compare RIB II.7, 2501.581), but there are other possibilities. Just to the right of N are two horizontal marks which might suggest a fourth letter ligatured to it, but since it would be incomplete and three-letter abbreviations are usual, they may be dismissed as casual.

39 L is not certain since it consists of a vertical stroke followed by the end of a second, detached stroke which is cut by the broken edge. But the cognomen Gemellus is very common.

40 During the excavation published as A. Woodward and P. Leach, The Uley Shrines: Excavation of a Ritual Complex on West Hill, Uley, Gloucestershire: 1977–9 (1993), in which it is noted at 129 as no. 68 (SF 3652). It is published with fuller commentary in the forthcoming proceedings of the Thirteenth FERCAN Workshop at Lampeter in October 2014, edited by R. Häussler and A. King.

41 Notes (a)

2. Probably Carin[us] or Carin[ianus], followed by a verb ending in -ro (3). This is likely to have been execro (active, as in Tab. Sulis 99, 1) or [obs]ec|ro, probably preceded by tibi or te respectively.

3–4. Pri|manus must be the name of the thief, but grammatically fecit would be required, or a Primano with factum est. The scribe confused two formulas, active and passive, neither of which is actually attested in Britain, but fraudem fecit is used at Bath and Uley, and quot mihi furtum factum est in the Mérida tablet (CIL ii 462).

5–6, nec [e]i per|mitt[ ]s. The formula of not ‘permitting’ the thief is frequent, but Mercurius is nominative, so permitt[at] in the third person is required, not permitt[a]s, for which anyway there is too much space. It is followed by a word ending in s, perhaps [nato]s, although it would be rather cramped; this would suggest he is being deprived of children, nec natos nec nascentes (Tab. Sulis 10, 13–15).

Notes (b)

1, nec. The sense evidently continues from (a), but the rest of the line has been crossed out by a series of more or less horizontal lines.

3, nec solem nec lun[am]. Contrasting sources of light denied to the thief, apparently, but the formula is new.

4. The word after nec looks rather like coniugis, but g cannot be read. The concluding infantis also suggests a family context.

6–7, san(g)uine suo conpliat | vendica[tionem]. The idea of ‘paying’ with one's blood is frequent, but this formula is new. The spelling is ‘Vulgar’, with g in san(g)uine lost by lenition; compare sanuene sua in Tab. Sulis 46, 7. conpliat is for conpleat, unstressed short e and i often being confused. This is not the case with vendica[tionem], but the form vendicas for vindicas is found three times in the London Bridge tablet (Britannia 18 (1987), 360, no. 1CrossRefGoogle Scholar, noting that it anticipates a change found in some Romance languages).

42 During excavation for North Hertfordshire District Council Museum Service, directed by Keith Fitzpatrick-Matthews, who provided details. The site, which was discovered by a metal-detectorist, is a rich burial dated by a very worn coin of a.d. 177/8. Kris Lockyear informed Mark Hassall, who noted the parallel cited below.

43 For another example, see RIB II.2, 2419.143 (Cramond) with note.

44 With the next four items during excavation by the Canterbury Archaeological Trust (Britannia 33 (2002), 352–3,Google Scholar and 34 (2003), 355). Mark Houliston made them available. They are CW9 <57>, CW64 <462>, CW46 <2330>, CW21 <4908> and CW64 <4480> respectively.

45 Only the first letter is complete. The fourth letter might be I, but the incomplete stroke looks a little close to L to be an entire letter. There are names in -hili- such as Philippus, but Hilarus (and its derivatives) are so popular that A is more likely.

46 It is not even clear that the graffito should be read this way up, but the initial letter is more acceptable as P than (inverted) as lower-case D. Next comes a clumsy V, but then D is made without a vertical stroke (this being supplied by V), and E with only a medial stroke. The popular cognomen Pudens could be read by supposing that N ran into S, the latter being indicated by a vertical downstroke followed by a diagonal upstroke. But this would leave unexplained the ‘letters’ which follow, themselves no more than a series of ambiguous diagonals.

47 The letters are all incomplete, but enough survives to make this the probable reading. There are many possibilities, including the popular cognomen Genialis.

48 The same sequence in capitals has already occurred at Canterbury, on the samian sherd RIB II.7, 2501.13, but there it seems to be the beginning of a word perhaps abbreviated, possibly tur(ma) (‘cavalry troop’). The present graffito is more likely to be part of a personal name, for example Saturninus.

49 All that survives of the fourth letter is part of a curve, and visually G, Q or O are also possible, but none would result in a sequence likely to belong to a personal name. The sequence -inic- offers many possibilities, including the nomina Minicius and Vinicius, and their derivatives.

50 PAS ref. LIN-4D3E76 (Daubney 82). As in Britannia 45 (2014), 443–4Google Scholar, TOT rings are noted by their reference-numbers in the PAS database and the catalogue kept by Adam Daubney, Finds Liaison Officer for Lincolnshire.

51 With the next item during excavation of the Roman site (Antiq. Journ. 50 (1970), 222–45CrossRefGoogle Scholar) by the Dragonby Excavation Committee directed by the late Jeffrey May, who made them available to Mark Hassall. They are now in the North Lincolnshire Museum, Scunthorpe. The first is DR64 CR from the excavation of 1964 (JRS 55 (1965), 205Google Scholar), the second is DR72 BKZ from the excavation of 1972 (Britannia 4 (1973), 286Google Scholar).

52 There are traces, faint but sufficient, of the top and bottom of the semi-circle representing c, and above them, larger and more deeply incised, as if to mark it as the initial letter, the top of s. Personal names in the genitive case, incised before firing on Dressel 20, indicate the potter or perhaps the workshop.

53 PAS ref. DENO-C47328 (Daubney 90).

54 PAS ref. NLM-2089B1 (Daubney 83).

55 PAS ref. LIN-DF32B4 (Daubney 85).

56 Like No. 56 below, both Ts are inscribed with exaggerated bottom serif formed by two diagonals.

57 PAS ref. LIN-F2DE0C.

58 With the next two items during work by MoLA (Britannia 45 (2014), 376Google Scholar), where Charlotte Burn made them available. They are TRN08 <467>, <237> and <475> respectively.

59 The sherd is broken close to P, but the graffito is probably complete. A is of early form with a third diagonal downstroke. This is the owner's name abbreviated to its first two letters, with many possibilities including the common cognomina Paternus and Paullus, both of which have been found in London (RIB II.7, 2501.412(?) and 426 respectively).

60 The ‘star’ consists of three intersecting strokes, its left-hand portion now lost. A is ‘open’ (without cross-bar). The ‘star’ is a mark of identification, followed by the owner's name, of which only the first two letters remain, Ar[…]. There are many possibilities, the most common being the nomina Arrius and Arruntius.

61 The ‘triangle’ can be read as capital delta, and the vertical line as capital iota. The ‘square’ (two horizontals crossed by two verticals) is not really like a Greek letter, but was perhaps a symbol or abbreviation. The graffito is noted here since it is complete, and somewhat resembles the graffito in Greek capitals on a beaker found in London at Mariner House (Britannia 43 (2012), 404, no. 14Google Scholar), which has been tentatively identified as an apothecary's jar.

62 With the next item during evaluation by MoLA (Britannia 44 (2013), 327Google Scholar), where Charlotte Burn made them available. They are MNR 12 <43> and <136> respectively.

63 S was scratched twice and extended by a single upward diagonal, the intention being perhaps to reinforce the initial letter. Solitus, although apparently Latin (‘accustomed’), like Solinus (RIB 22, London) incorporated the element found in Celtic names such as Solimarus and is found in Celtic-speaking provinces. In the feminine form Solita, as here, it is attested in the dative Solitae sorori (CIL xii 95, Brigantio).

64 A is incomplete, but apparently of early form with a third diagonal downstroke. The next letter is now only a nick in the corner of the sherd, but is too close to be T. It might well be part of II, i.e. E. The cognomen Laetus is quite common.

65 With the next item during work by MoLA (Britannia 45 (2014), 375Google Scholar), where Charlotte Burn made them available. They are MAL 13 <83> and <186> respectively.

66 The first ‘letter’ is apparently a medial point, which would imply it separated two words, the first perhaps abbreviated. Thus probably the owner's nomen and cognomen, the latter being Umber or a cognate: compare RIB II.7, 2501.633, Um(…), and RIB III, 3190, Lat(…) Um(…)

67 This name is quite common, and has occurred once before in London, abbreviated to ONII in a samian graffito from Drapers’ Gardens (Britannia 40 (2009), 344, no. 52Google Scholar).

68 In the same excavation by MoLAS as the pewter tablets published as Britannia 30 (1999), 375, no. 1CrossRefGoogle Scholar and 44 (2013), 390, no. 21. Jenny Hall made it available from the Museum of London (VRY 89 < 940>).

69 For charaktêres in general, see Gordon, R., ‘Signa nova et inaudita: the theory and practice of invented signs (charaktêres) in Graeco-Egyptian magical texts’, MHNH 11 (2011), 15–44Google Scholar. They are elaborations of Greek letters and geometrical figures. This tablet contains five also found in the Billingford amulet for health and victory (Britannia 37 (2006), 481, no. 51Google Scholar, with fuller commentary in ZPE 149 (2004), 259–66Google Scholar): the ‘lattice’ in lines 1, 3 and perhaps 4; the ‘barred lambda’ in 2 and 7; the ‘barred omega’ in 2, 3 and 4; the ‘star’ in 5 (but with five points, not six); the ‘HHH’ in 6 (but with horizontal incomplete). Line 7 begins with a ‘ring-letter’ elaborated from a Billingford sign (line 2, no. 3). Lines 2 and 3 end with ‘squares’ which are elaborated in 1 (with outer lines), in 4 (with rings), and in 5 (with kappa). There are also four unelaborated letters: chi in 2, 5 and 6; tau and omicron in 5; theta in 6.

70 During work by Oxford Archaeology South and Pre-Construct Archaeology (Britannia 42 (2011), 377–8Google Scholar). Edward Biddulph sent a photograph and details.

71 This is a popular name, often borne by slaves and freedmen. In origin Greek (‘secure against enchantments’), it is widespread in the western Empire. In Britain it has occurred on a moulded lead pig (RIB II.1, 2404.51) and a bronze die (RIB II.1, 2409.33).

72 With the next two items during excavation in advance of house-building directed by Simpson, F.G. and Richmond, I.A. (JRS 28 (1938), 172–3)Google Scholar. Alex Croom made them available from Arbeia Roman Fort, South Shields, as SF 136, 122 and 153 respectively. Also examined was a black burnished rim sherd (SF 131) scratched with two ‘crosses’ or ‘stars’.

73 This might be the numeral IV (‘4’), but is more likely to be a variant of (ii). Since it respects the ‘star’, or is respected by it, they seem to be only one graffito.

74 Iulius is a common Latin nomen, but is often found by itself as a cognomen.

75 The letters consist of straight or diagonal strokes, with short vestigial strokes marking the scribe's zig-zag sequence from left to right. One descender cuts IVLI (inverted), indicating that the scribe was an owner subsequent to Julius. Only the first three letters are at all certain, IAN, which is used as an abbreviation for Ianuarius since there is no other common name beginning with these letters. This suggests a blundered Ianuarius, although the sequence III is difficult and R is uncertain.

76 Primus and its cognates are common, and there may be another example from Benwell, another samian sherd (RIB II.7, 2501.442) which reads[…]PRI[…]

77 The incisions look as if they were made this way up, cutting from left to right. There is a hint that the scribe was about to cut a fourth X, but instead (after a slight space) cut V. This would confirm that he intended a numeral, not a repetitive pattern as a mark of identification.

78 PAS ref. NMS-065376, described by Adrian Marsden. Compare RIB II.3, 2422.15 (Brancaster).

79 Dom(i)nicus / Dom(i)nica (from dominus, ‘the Lord’) is typically Christian, and indicates a fourth-century date.

80 PAS ref. NARC-41DB75, fully described by Ralph Jackson.

81 S is reversed. The legend has not been resolved, but may be a garbled version of the VIVAS IN DEO (‘May you live in God’) formula found on other ‘Brancaster type’ rings like the previous item.

82 During the annual training excavation directed by Eric Birley and John Gillam. Frances McIntosh made it available (CO 2326), and Graeme Stobbs provided details. It is not in RIB II.6, 2493, nor in Britannia.

83 Line 2 is quite uncertain, but line 1 must be an ablative plural ending, that of a month, whether Septembribus, Octobribus, Novembribus or Decembribus, in which the day was either the Kalends (1st), Nones (5th, or 7th in October) or Ides (13th, or 15th in October), Kalendis, Nonis or Idibus, perhaps abbreviated.

84 With the next five items during excavation by the Vindolanda Trust directed by Andrew Birley; Barbara Birley made them available and provided details. Graffiti of less than three letters, except for No. 53, have been omitted.

85 RIB II.2, 2412 (at p. 1) accepts a figure of 327.45 gm for the Roman pound (libra), which would make this example 15.275 gm (8.53%) overweight.

86 Line 1 may be a personal name such as Aemilianus, but not a consular date, since this would have followed the day-date in line 2. There is no second-century pair of ordinary consuls Aemiliano et […].

87 A Roman citizen's three names reduced to their initials. Nomina in E(…) are less common than in F(…), but E includes a bottom stroke which cannot be an exaggerated bottom-serif of F.

88 PAS ref. LVPL-D46C37 (Daubney 89).

89 Like No. 33 above, both Ts are inscribed with exaggerated bottom serif formed by two diagonals.

90 With the next item during excavation by Tyne and Wear Museums (Britannia 41 (2010), 355Google Scholar, and 44 (2013), 287–8), IM 195 and IM 196 respectively. Alex Croom made them available.

91 There is a feature above both letters, perhaps only a suprascript line, but it looks as if it was intended for a swag suspending a portrait-roundel. It is absent from the rectangular D N sealing previously found at South Shields (Britannia 30 (1999), 383, no. 20Google Scholar), and to judge by the published drawing, the lettering of this is slightly different too; the same is true of the Corbridge example (Britannia 33 (2002), 369, no. 27Google Scholar). But even if the die is not quite the same, the sealings must be closely related. They may be attributed to a third-century sole emperor who used the title dominus noster, perhaps Caracalla; see further Britannia 30 (1999), 383, n. 32Google Scholar.

92 Despite its poor state of preservation, this looks like the same die as the previous item, with a hint of the ‘swag’ above N.

93 With the next item during excavation by Oxford Archaeology East (Britannia 43 (2012), 324Google Scholar). Alice Lyons made them available. Omitted here, but included in the final report, are two sherds inscribed with a single letter, ‘M’ and ‘A’; three with ‘crosses’; and one with a figure like ‘T’ terminating in two hooks, perhaps a stylised anchor.

94 C is much slighter, and may even be a casual mark. R, F and A are deeply incised, R and F with an exaggerated leftward bottom serif. The elongated I, despite being close to the broken edge, shows no sign of being part of another letter, for example L, N or V, unless it is the first stroke of II (an alternative form of E). But it may not be a letter at all, since the rather cramped A seems to be avoiding it. The graffito is literate and evidently the potter's signature, but even if it is reduced to RFA, it cannot be resolved into a name or date.

95 With the next two items during excavation by Pre-Construct Archaeology (Britannia 39 (2008), 328–9Google Scholar), and made available by Vicki Ridgeway. For previous graffiti from the site, see Britannia 42 (2011), 457–9Google Scholar, nos 26–28.

96 Possibly the numeral VII (‘7’), but much more likely to be a personal name abbreviated to its first two letters. There are many possibilities, including Vegetus, Venustus and Verecundus. Although the bottom of II is lost, VI[L] can be excluded, since names in Vil(…) are so rare.

97 Most likely Ba[ssus], but there are other possibilities.

98 G is made with three strokes, its horizontal being cut by the downstroke which terminates the graffito, so that ‘T’ should not be read. (In writing T, the downstroke would precede the horizontal.) The nomen Magius is quite common, and is probably Celtic, since magio- and -mago-s are such frequent name-elements; Ellis Evans also notes the element magu-, ‘youth, slave, vassal’ (Gaulish Personal Names (1967), 221–2). It must be cognate with the samian potters’ names Magio and Maginus (B.R. Hartley and B.M. Dickinson, Names on Terra Sigillata, Vol. V (2009), s.v.), and as a cognomen in the genitive case, Magi is found in the patronymic Bellina Magi (CIL xiii 2698).

99 Both verticals seem to have been made downwards, towards the foot of the foot-ring. They were each completed by a short horizontal stroke at the top, probably for T, since a numeral (‘2’) would have been denoted by a single stroke, and ‘serifs’ would have been repeated at the bottom.This is presumably an abbreviated personal name, […]ott(…). With the loss of the beginning, there are many possibilities, some of them like Cotta and Scottius hardly worth abbreviating. Perhaps it was a longer derivative, such as Cottalus.

100 By a metal-detectorist. Fraser Hunter sent a copy of his Treasure report.

101 The actual weight is 53.70 gm, which is only c. 1.6 per cent under two Roman ounces (54.58 gm).

102 With the next item during evaluation by CFA Archaeology (Britannia 42 (2011), 333–4Google Scholar). The sherds were identified by Colin Wallace, and details including photographs were sent by Fraser Hunter.

103 T F overlies faint scratches which might be an earlier owner's mark, but are probably casual. This extreme abbreviation of the imperial nomen is quite common, especially if preceded by T(itus), for example CIL iii 2329 (Salonae), T(itus) F(lavius) Silvanus. In Britain the other instances are F(lavius) Titianus (RIB 1083) and P(ubli) F(lavi) Hygini (RIB II.1, 2409.29).

104 There is no numeral to the right (for a note of capacity in m(odii)), so this is probably the owner's initial or distinguishing mark.

105 With the next two items during excavation by AOC Archaeology, <239>, <474> and <602> respectively. Alex Croom made them available, with two other samian sherds bearing marks of identification rather than letters: ‘H’ on <495>, and ‘IXI’ on <642>.

106 The graffito is complete, so it cannot be part of the note of capacity often found on the handles of Dressel 20. A numeral (‘55’) or a note of weight (‘5 pounds’) would be inappropriate, so it must be the owner's name abbreviated to its first two letters. An explicit LVC for Lucius or a cognate name might have been expected, but the curve of C would have been difficult to make.

107 O and E (unless it is F) seem to be broken at mid-height, which suggests that the intervening letter is X rather than a diminutive V. It is followed, rather closely, by a vertical stroke which is presumably I, but between it and E is the beginning of a vertical scratch which might just possibly be the second stroke of L. This is presumably the owner's name, but nothing can be suggested.

108 (i) is now incomplete, and it is uncertain whether this graffito consisted of a single letter like the others, which are presumably the initial letters of the names of successive owners. On the outer wall, immediately above the foot-ring, the surface has been planed away over an area c. 65 by 12 mm, suggesting yet another owner's name has been erased. The curve of (ii) is not very marked, and L would be possible. It was apparently succeeded by (iii), since it consists of two strokes meeting at an acute angle which coincides with the bottom of (ii), with regard to which it is inverted. ‘Open’ A (without cross-bar) is thus possible, but looks less likely than V.

109 During excavation for Reading University directed by M. Fulford and A. Clarke (Britannia 45 (2014), 386Google Scholar), SF 96, who made it available. It was found in the backfill of an 1891 trench in Insula III. The 1891 fragment is stored by Reading Museum (acc. no. 1995.1.15), where Jill Greenaway made it available for direct comparison.

110 The 1891 fragment, 175 by 245 mm, preserves the original thickness of 54 mm. The inscribed panel is dished by 3 mm, and the bottom border is 51 mm wide, with an incised line 6 mm wide cutting it 34 mm from the base. These dimensions are all matched by the new fragment, and also (by estimation) the letter-height of 61 mm.

111 In the broken edge of the 1891 fragment, to the right of T, there is the upper portion of an incised vertical stroke, as the drawing of RIB 76 implies but the transcript does not note. This can now reasonably be read as R. Another reference to the civitas Atrebatum is probable in RIB 73, a conjecture by Haverfield accepted by Boon (Silchester (1974), 116).

112 As noticed by Scott Vanderbilt when constructing the on-line Roman Inscriptions of Britain.

113 By Peter Ryder, who informed Paul Bidwell, who noticed its similarity to RIB 1508. It is now built into the external face of the blocking of a former doorway near the north end of the east wall of the western of the two outbuildings just north of the Hall, c. 0.60 m above the ground. When it was seen by Hunter (1702), it was still in the face of Hadrian's Wall which had been repaired ‘and fronted with its old Stones again’. When the Wall here was demolished in 1755 to make the Military Road, Stukeley's correspondent John Walton was ‘expecting some inscriptions which were promised me from Walwick, which I have not yet got. They are only of the centurial sort, many of them, though not all, before published.’ He had vainly hoped ‘that some remains of antiquity might be found in the making of the road along the wall west of Walwick. Nothing has been found more than some centurial inscriptions …’ which he does not identify (letter of 24 February 1755, published in The Family Memoirs of the Rev. William Stukeley, III, by the Surtees Society, Vol. 80 (1887), 131–3). If RIB 1508 was among them, it must have been salvaged with other facing-stones for re-use locally.

114 In line 1, COH is still quite legible, but only the first diagonal of VI remains; the whole of it was drawn by Hunter (fig. 46), and its existence is confirmed by RIB 1678 (with note), but it was already missing from Horsley's drawing (reproduced in RIB) which shows the corner broken. In line 2, the centurial sign and LI remain as drawn by Hunter and Horsley, with the traces of E resembling B, which is how they both drew it. Little now remains of line 3 except the top of A: the stone was evidently reduced after it was drawn by Horsley.

115 A.R. Birley, ‘Roman roadworks on the Vindolanda stretch of Stanegate’, Epistula VIII, 7. RIB 2313+add. is the only other British milestone to name an auxiliary cohort.

116 Information from the former curator, Ken Reedie, communicated by Thomas Goessens of the University of Kent at Canterbury, who provided the substance of this entry and the next which he will publish more fully. The Museum was founded by the Canterbury Philosophical and Literary Institution in 1825, of which Baldock (see further next note) was Director from 1828.

117 Watkin saw it in Canterbury in 1875, without knowing (or at least saying) that it was owned by Fanny Ellen Pout, whose father had been Librarian of the Canterbury Philosophical and Literary Institution of which William Baldock was Director. The latter was a Canterbury banker who lived in Petham during 1812–43, but he was declared bankrupt in 1841, when the tombstone must have been acquired by Mr Pout, whether by gift or purchase. Miss Pout bequeathed property to Frank Wacher, the father of Harold Wacher, from whose estate the tombstone was acquired by the British Museum (JRS 19 (1929), 216Google Scholar).

118 Made from rubbings by R.P. Wright, who first published it. It has now been re-drawn from the original.

119 The script is fluent but employs quite a small range of elements, and in 6 the scribe's eye evidently slipped from int to ent, producing the syncopated int(ent)iq[ue]. The reading conticuere is certain, and guarantees that this is the famous Vergilian tag (Aen. 2.1) of which the first two words occur on a tile from Silchester (RIB II.5, 2491.148, with note).

120 By Corbridge Roman Site when consulted by the new owner. Frances McIntosh made it available, and provided details.