Among the many portraits of early modern Habsburgs, one in particular stands out. This striking painting depicts Archduke Matthias Habsburg (1557–1619) standing tall against the battlefield. Clad in an ancient armor with a laurel wreath on his forehead, Matthias is posing as Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus (236/235–183 BC), the famous Roman general celebrated for his campaigns against Carthage (figure 1). The confidence exuded by Matthias in this portrait is, however, misleading of his actual position at the time. Painted in 1580 by the Archduke's longtime court painter, Lucas van Valckenborch (ca. 1535–97), this portrait was completed at a particularly turbulent time in Matthias's life. Only three years earlier, Matthias had taken part in a cloak-and-dagger intrigue which saw him leave, under the shroud of night and against the wishes of his family, the dynasty's imperial court in Vienna to assume the position of Governor-General of the Dutch provinces. This turned out to be a bad gamble. Matthias lost the trust of his family and earned the reputation of a political adventurer among his contemporaries. Meanwhile, his new position in the Low Countries proved to be a thankless one. Matthias found himself with his hands tied, as his Dutch hosts constricted his political and military prerogatives. Because of his hope that his luck might turn, on the one hand, and, limited alternatives, on the other, Matthias decided to remain in the Low Countries. At the time of the painting's completion, though, Matthias's governorship was already living on borrowed time. Matthias's decision to be portrayed as a celebrated Roman hero thus reflected the Archduke's aspirations rather than his actual position. In this respect, the painting was not unlike many other portraits of early modern rulers, which, in the words of Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann, were “not merely forms of representations,” but could also serve as a ruler's vision of the “ideal self.”Footnote 1 Matthias's portrait, however, ought not be so quickly dismissed, as it was not a mere exercise in self-aggrandizement. Indeed, Matthias's choice to be depicted as Scipio Africanus was far from random: it presented an important example of the concerted efforts among members of the Habsburg dynasty to draw associations between themselves and this ancient hero.Footnote 2

Figure 1. Lucas van Valckenborch, Archduke Matthias Habsburg as Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus, 1580, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Gemäldegalerie, 1022. © KHM-Museumverband.

Scipio Africanus was, of course, one of many individuals from antiquity, both historical and fictional, embraced by the Habsburgs in the early modern period, and the way in which these associations have been conceptualized may be the reason why the Habsburgs’ identification with Scipio has so far evaded scholars. In early modern Europe, the ancient past was studied and searched for examples relating to the present; it presented a repository of material to be used, recycled, and adapted to contemporary needs and purposes. It has been established that the Habsburgs attached special significance to fostering associations between themselves and the ancient past. While many royal and noble houses traced their roots to individuals and events from antiquity, the Habsburgs based their power, and especially their leadership of the Holy Roman Empire, on these claims of ancient ancestry.Footnote 3 This conviction of ancient lineage was shared among the Habsburgs, providing a degree of unity and uniformity to the dynasty as it spread across the continent. References to antiquity thus supplied the Habsburgs’ symbolic repertoires. As Clifford Geertz and other cultural anthropologists have illuminated, the manipulation of shared symbols has aided the consolidation, or indeed construction, of power across ages.Footnote 4 The early modern world was no different. Though rarely studied individually, the images comprising symbolic repertoires have thus been traditionally understood, both in reference to the Habsburgs and others, to bolster the position of those who used them, whereby the virtue, merit, and accomplishment associated with such images reflected back on those who evoked them. They formed a fabric of what Randolph Starn referred to as a culture of triumphalism, a formula for the representation of power in early modern Europe.Footnote 5

In recent decades, though, the attention of art and sociocultural historians studying early modern displays of power has shifted from form and style to function and context, prompting scholars to see symbolic repertoires as more than collections of stock images. Writing about early modern festivals, Roy Strong has remarked that these occasions were “crammed with contemporary comment, but in a language that is today virtually incomprehensible as a means of presenting a program of political ideas.”Footnote 6 These observations could be easily applied to the early modern world more generally. While typically intelligible across time, space, class, and gender, these images were, as J.R Mulryne has stated, “sensitive, against familiar assumptions, to the micro politics of personal relationships” which was vital to their suasive role.Footnote 7 This is not a new realization. Already in the early modern period, art theorists argued that while representations of the past were to depict people and events in a way that was no longer bound to time and space, these images were to be selected and displayed in such a way as to compliment the occasion that they adorned.Footnote 8 These considerations informed the Habsburgs’ use of these images; as scholars have pointed out, the dynasty's symbolic repertoires underwent changes, modifications, and adjustments, but our understanding of these variations is still wanting.Footnote 9

Tracing the Habsburgs’ uses of Scipio Africanus not only brings to light an important, though so far overlooked, strand in the dynasty's symbolic repertoires; it also lends itself to address more fundamental questions about the dynasty and its relationship with these images. This article begins by contextualizing Scipio Africanus in the intellectual and cultural landscapes of early modern Europe. It then establishes how in the early sixteenth century the initial associations between the Habsburgs and this Roman hero were forged and explores how Scipio Africanus was reinterpreted and appropriated by subsequent generations of the dynasty. Various members of the dynasty drew associations between themselves and this Roman hero throughout the early modern period. By the middle of the sixteenth century, their uses of this image coalesced around two distinct—and ultimately competing—interpretations of Scipio Africanus. The final section focuses on the clash between these two interpretations of Scipio Africanus in late-sixteenth-century Low Countries and explores how in the aftermath of this conflict Scipio was retired and eventually reclaimed by the Habsburgs. The argument of this article is that Scipio Africanus was more than an evocative, but ultimately easily replaceable, stock image. The Habsburgs’ adoption of this Roman hero into their symbolic repertoires added to the dynasty's grandeur in the obvious way such images generally did. But Scipio Africanus also carried a more profound significance for the Habsburgs: his image was used in ways that were revealing of the dynasty's conception of power as well as the identities, needs, ambitions, and struggles of individual Habsburgs. This made Scipio Africanus a powerful image, which was capable of elevating the Habsburgs, but which also rendered them vulnerable.

I

One of the most successful military commanders of antiquity, Scipio Africanus was a celebrated figure in the history of the Roman Empire.Footnote 10 Born into a leading patrician family, Scipio achieved fame as a young man during Rome's struggles against Carthage in the Second Punic War (218–201 BC). In the early years of his military service, Scipio distinguished himself as a man of valor and patriotism. Scipio saved his father's life during the Battle of Ticinus (218 BC). Two years later, several Roman leaders sought to desert Rome following its defeat in the Battle of Cannae (216 BC), Scipio stormed into their meeting, and at sword-point, forced all present to swear that they would not abandon Rome. After his father was killed in battle, Scipio offered himself for the command in Spain. He was then unanimously elected and went on to lead a successful campaign against Carthage. Taking advantage of disagreements among its leaders and their involvement in the revolts in Africa, Scipio unexpectedly attacked and captured New Carthage (209 BC), the headquarters of Carthaginian power in Spain. According to ancient historians, Scipio owed his success in winning over these lands to his merciful treatment of the local population. Scipio then attacked Carthage's headquarters in Africa and later gained a crushing victory over the Carthaginian leader, Hannibal, near Zama (202 BC). Scipio was welcomed back to Rome in triumph—the highest possible honor awarded for exceptional military achievement—and received the name Africanus. Some years later, Scipio was charged with peculation. On the day of his trial, however, by reminding the people that this was the anniversary of Zama, he was acquitted amid great acclamations, after which he retired into private life.

The story of Scipio Africanus was commemorated by ancient artists and authors, whose works were examined with renewed interest in the early modern period. From widely distributed prints to monumental frescoes, from private quarters to state buildings, from wedding ceremonies to celebrations of military triumphs—the life of Scipio became one of the most popular narrative cycles in early modern Europe (figures 2 and 3).Footnote 11 While artists popularized Scipio's story, authors meditating on his deeds and character added nuance to his life. It was principally through the works of Petrarch (1304–74) that, from the fourteenth century, Scipio was celebrated as one of the most famous ancient heroes. The culture that emerged in Italy at that time, and subsequently spread across the continent, turned “the admiration for ancient authors that had long existed in medieval culture into a kind of Sehnsucht, a longing for the restoration of lost qualities of mind, for the return of ancient virtue.”Footnote 12 It gave rise to what James Hankins dubbed as virtue politics—a strand within early modern political thinking which sought to improve the character and wisdom of the ruling class to bring about a flourishing commonwealth.Footnote 13 Scholars have considered Petrarch to be the father of this movement for the recovery of ancient virtue; Petrarch, in turn, considered Scipio to be the perfect embodiment of this ancient virtue.Footnote 14 Scipio featured in many of Petrarch's works, who devoted to the Roman hero his unfinished magnum opus, Africa, an epic account of Scipio's achievements in the wars against Carthage. In the only treatment of the subject to date, Aldo Bernardo has argued that it was Scipio, not Laura, who was Petrarch's chief muse.Footnote 15 From reiterating the ancient historians’ suggestions of Scipio's divine parentage, to praising his military skill and virtues, Petrarch portrayed Scipio as an all-round Roman hero. Not all early modern thinkers, though, shared such an idealized view of Scipio. Machiavelli (1469–1527), for instance, put into question Scipio's virtue, especially his gentle treatment of conquered populations. While admitting that Scipio did, in fact, treat the conquered with mercy, Machiavelli saw it as a political strategy rather than evidence for his personal virtue.Footnote 16 Machiavelli also questioned whether Scipio's merciful treatment of the conquered was, in fact, the superior strategy, by pointing out that his main adversary, Hannibal, employed means contrary to those and attained similar results.Footnote 17

Figure 2. Cornelis Cort, The Battle Between Scipio and Hannibal at Zama, ca. 1550–78, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 59.570.439. © Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1959.

Figure 3. Francesco Durantino, Plate with The Continence of Scipio, ca. 1545, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 94.4.332. © Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of Henry G. Marquand, 1894.

Ultimately, however, early modern narratives of Scipio's life coalesced around his merciful treatment of the conquered. The key example of that was the story of Scipio returning a bride to her family. As recorded by Livy, Scipio's troops captured a beautiful woman, whom they offered to Scipio as a prize of war. Scipio was astonished by her beauty, but upon discovering that she was betrothed to a local chieftain, decided to return her to her family, along with the money that had been offered to ransom her, in return for their loyalty to Rome.Footnote 18 Both Petrarch and Machiavelli recounted this story when discussing Scipio's deeds. So did others. In The Education of a Christian Prince (1515), Erasmus (1466–1536) evoked the image of “Scipio restoring to a young man his betrothed wife untouched and rejecting the gold which was offered to him,” as an example of commitment to state business that ought to be replicated by rulers.Footnote 19 Francis Bacon (1561–1626) described Scipio as an example of a man who was “magnanimous, more than tract of years can uphold.”Footnote 20 This reading of Scipio transcended confessional divides. Martin Luther (1483–1546) praised on multiple occasions Scipio's choice to conquer rather than destroy Carthage as well as him returning the bride to her family.Footnote 21 Writing on the other side of the confessional divide, the Italian Jesuit, Giovanni Botero (ca. 1544–1617) observed: “what is more beloved than honesty? Nonetheless, that outstanding action of P[ublius]. Scipio when he returned that most beautiful young woman untouched to her husband, did not make him so much beloved as admirable, and it gained him such esteem and reputation with all that the Spaniards held him to be nearly a god descended from heaven.”Footnote 22 Scipio thus emerged from these narratives as a virtuous ruler, one able to moderate his own appetites and rule with equity, justice, and magnanimity. In the early modern world of virtue politics, where good character and political wisdom of rulers were celebrated as the true cornerstones of legitimacy, Scipio presented an important example of rulership.Footnote 23

It was within such context that at the turn of the sixteenth century, the initial associations were forged between Scipio Africanus and the Habsburgs. Though this Roman hero might have been evoked by earlier Habsburgs, the first member of the dynasty to be identified with Scipio in a substantial way was Archduke Philip (1478–1506), the son of Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I (1459–1519) and his wife Mary of Burgundy (1457–82).Footnote 24 Philip was a prince of promise. Through his father, he was an heir to the Habsburgs’ hereditary lands in Central Europe and through his mother, to the wealthy Duchy of Burgundy, while his marriage to Joanna of Castile (1479–1555) provided him with access to the Spanish lands. It was precisely Philip's involvement in Spain—the land which previously had been central to the rise of Scipio Africanus—that lent itself to drawing associations between the Archduke and this ancient hero. In 1502, Philip and Joanna traveled to Spain to secure her Castilian inheritance. By January 1504, they had arrived back in the Low Countries, where lavish celebrations were organized to celebrate their safe return. A panegyric, a formal public speech delivered in high praise of a person or thing, was also commissioned for that occasion. The author of the panegyric was none other than Erasmus, who at the time sought to secure patronage at Philip's court. He delivered the speech in person during the festivities held on 6 January 1504 in the ducal palace in Brussels.

Erasmus devoted much of his speech to drawing associations between Philip and Scipio Africanus. He began by expressing his and the people's joy upon Philip's return; he declared it the “day of all days, the brightest and most auspicious for our country, and for any nation up to the present day and even in times to come.”Footnote 25 Of Philip's recent journey to Spain, Erasmus said that “Rome could have felt no more anxious concern when she once bade farewell to Scipio.” He then compared Philip's journey with Scipio's triumphant entry to Rome.Footnote 26 “Amongst countless Roman triumphs there was none, I think, so joyous as that of Scipio Africanus after his defeat of Hannibal,” Erasmus reminded his listeners, but also noted that Scipio's triumphant procession through Rome was only held for one day and the “spectacle gave pleasure anywhere but in Rome.”Footnote 27 Philip's journey, on the other hand, was a triumph in and of itself. “Wherever you led your steps, every place resounded with cries of delight, congratulations, and applause,” asserted Erasmus and asked rhetorically, “[h]ow else, most fortunate Philip, could the whole of your progress through France, Spain, and Germany be described but as a continuous triumph which surpasses all others in joy, in grandeur, and in magnificence?”Footnote 28 Philip could hardly boast achievements comparable to those of Scipio, so these comparisons must have flattered the young prince.

But flattery was not the only, or indeed principal, reason why Erasmus sought to draw associations between Philip and Scipio. These comparisons lent themselves to position Scipio as a model of rulership for Philip in a way that reflected contemporary preoccupation with virtue. After pointing out that Philip and Scipio were of a similar age when the former undertook his journey to Spain and the latter was first assigned command against Hannibal, Erasmus, conscious of the many references made throughout his speech, admitted:

For my part, Philip, I often compare your Highness with this general, who seems to have been endowed by heaven more than anyone else with so much beauty, dignity, intelligence, skill, wisdom, and good fortune for the exercise of authority, and I do so gladly, not without a happy feeling of presentiment.Footnote 29

Erasmus also conveyed a specific vision of the kind of man, he thought, Scipio Africanus was, and Philip might become. Erasmus's interpretation of Scipio was largely indebted to Petrarch's reading of the Roman hero as the embodiment of virtue. It was Scipio's “moderation,” in particular, which Erasmus sought to bring to Philip's attention. Erasmus asserted that no one was “so deadly to the enemy and yet so well liked in his day” as Scipio.Footnote 30 Yet, while Scipio's moderation earned him the envy of some, Philip's partaking in the same virtue, Erasmus argued, did not pose such a threat. Indeed, it would be the cause for Philip's “universal popularity and acclaim.”Footnote 31 Erasmus encouraged Philip to persevere in moderation, because it would serve him well in the future. “There must be no fears that your moderation in times of peace will shine less gloriously in the future than other men's bravery in deeds of war; for it is only the trappings of war which men admire, and not all men at that, nor even the most sensible among them.” Erasmus assured Philip and contended that “deeds performed quietly, thoughtfully, moderately, and justly are admired by all the best men, and indeed by all men alike, and not only admired but loved.”Footnote 32 To prove his point, Erasmus evoked the story of Scipio Africanus returning the bride to her family: this single act won Scipio, Erasmus argued, as much glory as did his capture of Carthage and the defeat of Hannibal.Footnote 33

Erasmus's choice of Scipio Africanus—and the qualities that he represented—as an example for Philip was far from arbitrary and went beyond contemporary concern with virtue. Indeed, it can be linked to the philosopher's views on the dynasty's management of the Dutch provinces. While Erasmus was eager to secure the dynasty's patronage, he was not necessarily supportive of its politics, which resulted in the decline of some of the province's noble houses. He was particularly critical of Maximilian I's engagement in military conflicts, which he saw as an effort to exact money from the provinces. Erasmus hoped that Philip might choose to follow a different path; Scipio's “moderation,” which he praised in the panegyric, presented an example of rulership that Erasmus hoped Philip would embrace. Indeed, Philip might have been receptive to Erasmus's proposals. Though his reaction was not recorded in the surviving sources, there are indications that Philip liked Erasmus's work, as the panegyric was printed by Dirk Martens in Antwerp only a month after it had been delivered in front of Philip. Erasmus was also generously rewarded by the Archduke—fifty Holland pounds, plus another ten pounds a couple of months later, which equated to more than one-third of an annual salary of the highest-ranking official of Haarlem at the time.Footnote 34 Ultimately, the prince's premature death two years after the speech's delivery prevented him from putting Erasmus's ideas into practice.

II

The association between Scipio Africanus and the dynasty, however, did not end with Philip's death and was perpetuated by the next generations of Habsburgs. Erasmus, who continued to enjoy the dynasty's patronage, might have brought this Roman hero to the attention of Philip's heirs. Among them, it was Philip's eldest son, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (1500–58), who embraced Scipio Africanus, though in a way that departed from Erasmus's ideas. In 1519, he succeeded his grandfather in the dynasty's hereditary lands and the Holy Roman Empire; it was during the celebrations of his imperial coronation which were held in Bologna a decade later that the initial associations between Charles and Scipio Africanus were first forged. Though the celebrations took place in Bologna instead of Rome, where imperial coronations were traditionally celebrated, Bologna was decorated in such a way as to resemble the eternal city.Footnote 35 As André Chastel has posited, Charles's entry to Bologna marked a watershed in the history of imperial coronations because it swapped traditional references to recent imperial history for references to ancient Rome.Footnote 36 Indeed, Charles's progress included depictions of the ancient Roman emperors, gods, muses, generals, and senators. Scipio Africanus first appeared on the arch decorating the city gate of San Felice, which was embellished with medallions depicting Roman rulers—Caesar, Octavian, Titus, and Trajan—whom the Habsburgs counted among their ancestors. Scipio was, however, depicted in a more distinguished way; the arch included a full-length statue of him, which was accompanied by a smaller statue of his adoptive grandson, Scipio Africanus the Younger (185–129 BC), who followed in his grandfather's footsteps, completing the destruction of Carthage.Footnote 37 Overall, Scipio's presence in Charles's symbolic repertoires at the time of his coronation celebration can be viewed as a part of a larger shift in the Habsburgs’ symbolic repertoires, which saw them incorporate the imagery of ancient Rome to present themselves as its rightful heirs.

Yet, following these cursory references, Scipio soon became one of the key features in Charles's symbolic repertoires, as the emperor began to draw personal associations between himself and the Roman hero. Such associations were solidified in the decade that followed his imperial coronation, after Charles's conquest of Tunis in 1535. The city had been one of the latest territorial losses suffered by the Christians to the Ottomans, who, under the administration of Suleiman the Magnificent (1494–1566), were making inroads into Central Europe and the Mediterranean. Following the Ottoman conquest of Tunis in 1534, Charles engineered an alliance of Christian and Muslim powers to recapture Tunis. The purpose of Charles's campaign was symbolic as much as it was military. The large army headed for Tunis was accompanied by artists, poets, scholars, and historians, who documented Charles's triumphs in Africa.Footnote 38 Even before embarking on the campaign, Charles had plans drafted for a celebratory procession through Italy, which scholars have deemed “the most significant triumphal progress of the century.”Footnote 39 The campaign lent itself well to drawing associations between the emperor and Scipio Africanus, as Tunis was built very close to where Carthage, conquered by the Roman hero and destroyed by his grandson, had formerly stood.

Comparisons between Scipio and Charles thus permeated the emperor's festive progress through Italy, which immediately followed his conquest of Tunis. It began with Charles's entry to Messina, where on the facade of the Duomo, the two columns referencing the Pillars of Hercules—Charles’s device included in his coat of arms—were surmounted by the heads of Scipio and his enemy, Hannibal. Toward the end of the entry, as Charles was approaching the cathedral church, angels descended from an artificial sky and stars to present Charles with a trophy, while Scipio depicted on one of the columns proclaimed Charles's prowess.Footnote 40 In his subsequent entry to Naples, the decorations included a statue of Scipio Africanus, which was juxtaposed with paintings of Charles's recent triumph in Africa. These featured the battle of La Goletta, the capture of Tunis, Charles releasing Christian captives, and the coronation of the emperor’s protégé as the new king of Tunis.Footnote 41 In the subsequent entry to Rome, the images of the two Scipios were displayed on one of the arches and their triumphs were depicted on the two towers of the gate of Porta San Sebastiano; these images were again juxtaposed with depictions of Charles's recent triumphs in Africa.Footnote 42

At the heart of these displays was the notion of Charles as “the new Scipio.” Charles was referred to as “Africanus” during his entry to Messina.Footnote 43 In Naples, as Charles was passing the statue of Scipio, he was again declared the heir to the ancient hero.Footnote 44 In Rome, the arch displaying the triumphs of the two Scipios referred to Charles as “ROMANUS IMP. AUG. TERTIUS AFRICANUS.”Footnote 45 Charles's costumes for these entries also blurred the distinction between him and Scipio Africanus. He had a suit of armor made with the image of Scipio on it and the inscription “CARTHAGINE,” which he wore for his entry to Naples, and possibly also other festivities.Footnote 46 Weaponry made for the progress were also embellished with such references. An example of that is a pageant shield which Charles likely carried during the festivals; attributed to Girolamo di Tommaso da Treviso (ca. 1497–1544) and based on a design by the painter Giulio Romano (1492/99–1546), the shield depicts Scipio's victorious storming of New Carthage.Footnote 47

By identifying with Scipio Africanus, Charles bolstered his image. Located far from the Ottoman heartland, Tunis was of peripheral interest to the Ottomans at the time.Footnote 48 The comparisons of Charles's conquest of Tunis to Scipio's campaigns thus added gravity to the emperor's symbolic, but otherwise modest, achievement. Charles's identification with Scipio also played well into the Habsburgs’ larger goal to present themselves as divinely appointed leaders of Christendom. The image of Scipio embraced by Charles referenced the ancient claims of Scipio's divinity, which had been reiterated by Petrarch, and ascribed this quality to Charles. During the entry to Messina, Charles was greeted by a representation of Scipio Africanus with the words: “Charles, you will be divine, you will be Africanus.”Footnote 49 While the depictions of Scipio and Charles's deeds were typically displayed alongside one another, they were also accompanied by references to the Ottomans; in Rome, for instance, the arch depicting Scipio Africanus described Charles as “the destroyer of the Turks” and the man who “made the Muslims pale with fear.”Footnote 50

Charles relied on his association with Scipio Africanus in formulating his image beyond his triumphant progress through Italy and the Roman hero became a permanent fixture in his symbolic repertoires. Several published accounts of the progress preserved its memory and promulgated its message, while objects, such as pageant shields, circulated across early modern Europe. The Habsburgs, meanwhile, continued to commission objects that perpetuated the notion of Charles as the new Scipio. Medals, relatively inexpensive and portable, presented one type of medium through which this narrative was popularized. One surviving example, dated around 1535, depicts Charles with a laurel wreath on his forehead on one side and Scipio with prisoners thanking him for freeing them and Roman soldiers collecting spoils on the other side.Footnote 51 In a way similar to the designs of Charles's festive progress through Italy, the medal juxtaposed the achievements of Charles with those of Scipio.

It was, however, tapestries that provided the most overt manifestation of these efforts to cement associations between Charles and Scipio Africanus. Being the most expensive artistic medium at the time, tapestries were in themselves signifiers of high social standing. Thanks to their size and intricacies of design they also lent themselves well to convey the more complex ideas of power.Footnote 52 In 1544, Charles's sister and governess of the Dutch provinces, Mary of Hungary (1505–58) purchased a seven-piece set entitled The Story of Scipio from Erasmus Schatz, the Fugger agent based in Antwerp.Footnote 53 Mary’s edition comprised tapestries depicting Scipio's capturing of Carthage, continence of Scipio, Romans attacking the entrenched camp of Asdrubal, meeting of Scipio and Hannibal, and battle of Zama, the triumph of the oxen and elephants, and the banquet. This set of tapestries served as a counterpart to another set of tapestries acquired by the Habsburgs around that time. In 1546, only two years after Maria's purchase of The Story of Scipio, Charles commissioned a set of twelve tapestries portraying his recent Tunis campaign. He remained actively involved in the production of the tapestries, exchanging letters with his sister regarding the progress of the work. By 1554, the colossal tapestries, based on the sketches by Jan Cornelisz Vermeyen, who had accompanied Charles on the Tunis campaign, and woven in the workshop of Willem de Pannemaker, one of the preeminent tapestry weavers in Brussels, had been completed.Footnote 54 Not only did the Tunis set reference the story of Scipio, but, as Lisa Jardine and Jerry Brotton have pointed out, the two sets also shared visual and thematic parallels.Footnote 55 These similarities and connections were far from coincidental; much like the earlier designs of Charles's progress through Italy which juxtaposed the deeds of the emperor with those of the Roman hero, the two tapestry sets simply reinforced these associations in a more visually impressive way.

Apart from playing into Charles's larger vision for his imperial reign, his identification with Scipio spoke to some of his more specific concerns, such as his rivalry with the king of France, Francis I (1494–1547). By the early sixteenth century, the Habsburgs had encircled the French possessions, which later prompted Francis to challenge the dynasty. In 1519, Francis stood as Charles's main competitor in the imperial elections. Having failed to secure the imperial throne, Francis continued to challenge the Habsburgs in other ways, including costly on-and-off wars in Italy. Most egregiously, however, during Charles's 1535 Tunis campaign, Francis allied with the Sultan. This political rivalry fueled a fierce personal rivalry, which, outside of political and military arenas, was conducted symbolically. For instance, following the battle of Pavia in 1525, during which Francis was captured and subsequently held captive in Madrid, the emperor commissioned a tapestry depicting his victory.Footnote 56

The figure of Scipio Africanus was central to this rivalry. Before Charles solidified the association between himself and this Roman hero, Francis had begun to present himself as the next Scipio. Following the imperial coronation in 1530, a design for a set of tapestries depicting the story of Scipio was first offered to Charles. However, he declined the offer, most likely for financial reasons.Footnote 57 The set was then commissioned on behalf of Francis by the Italian entrepreneur, Marchio Baldi, and produced by the Brussels workshop of Marc Crétif. The entire series owned by Francis consisted of twenty-two tapestries, thirteen of which chronicled Scipio's deeds, while the rest portrayed his triumph. They became an important part of Francis's image, especially in the context of his rivalry with the Habsburgs. The tapestries were displayed on occasions when Francis sought to form alliances against the Habsburgs, including his meeting with Henry VIII (1491–1547), held at Boulogne in October 1532, and then again at a carnival banquet held at the Louvre in Paris in February 1533.Footnote 58 Charles and Francis were well aware of their competing claims to Scipio. They even employed the story of the struggle between Scipio and Hannibal—through a staged sea battle—when in 1538, they met at sea outside Marseilles as part of their peacemaking ceremonies to resolve their conflicts in Italy.Footnote 59

Charles's identification with Scipio, however, presented a particular challenge to Francis, mainly because Charles proved to be more skillful and resourceful in promoting himself as the next Scipio. While the 1538 festival left it to the audience to decide whether Charles or Francis was represented by Scipio, Charles was more likely to be associated with the Roman hero, having completed his triumphant progress through Italy only three years earlier. The outcomes of the negotiations, too, gave Charles the upper hand, as, according to the truce, he remained in possession of the Duchy of Milan, which Francis was so determined to acquire. Charles also effectively challenged Francis's claim to Scipio by adopting the imagery previously employed by the French king. In fact, the set of tapestries portraying the story of Scipio purchased by Mary of Hungary was a reduced version of the series which was owned by Francis. Charles not only embraced these images, but also built on them in his depictions of his recent achievements in Africa portrayed in the Tunis set, which, in the words of Lisa Jardine and Jerry Brotton, presented a “politically devastating response” to Francis's “particularly tenuous and potentially rather uncomfortable” identification with Scipio, making the Tunis tapestries “the most skillful and terrifying series to emerge from the Low Countries in this period.”Footnote 60

Charles's association with Scipio Africanus was thus of importance in the construction of his image and power. But it is also significant in the considerations of the dynasty's symbolic repertoires for another reason. The way Charles deployed the image of Scipio Africanus signified a departure from the dynasty's earlier interpretations of this Roman hero. While the Habsburgs initially employed this Roman hero as the model of virtuous ruler, Charles evoked Scipio as a conqueror. Admittedly, mentions of Scipio's moderation, which had been central to earlier discussions of his virtuous character, made their way into Charles's iconographic apparatus, but they were few and far between. Even in the tapestry sets, which included a depiction of Scipio returning the bride to her family, the Roman hero's moderation was overshadowed by the numerous illustrations of his military prowess and subsequent triumphal celebrations. Scipio Africanus, as he was envisioned in Charles's symbolic repertoires, was first and foremost a conqueror.

III

Though Charles's successors refrained from launching campaigns in Africa and failed to keep hold of Tunis, which was recaptured by the Ottomans in 1574, they were eager to cultivate the association between the dynasty and Scipio Africanus well into the seventeenth century. This legacy, however, proved not to be a simple one. By the middle of the sixteenth century, the Habsburgs had formulated two distinct versions of Scipio Africanus. This plurality in the interpretations of Scipio was picked up on by the Habsburgs, who at the time struggled with pluralism within their own ranks. Charles's abdication as Holy Roman Emperor in 1556 resulted in the division of the Habsburg dynasty into the Spanish and Austrian branches. Though the Habsburgs sought to preserve their internal unity, differences between the two branches eventually started to emerge as they increasingly began to be guided by their individual, often divergent, interests. These tensions made themselves felt particularly strongly in the Low Countries. This was no accident. The Low Countries remained one of the most problematic territories for the Habsburgs. The provinces’ relationship with the Habsburgs was marked by Ambivalence: on the one hand, the dynasty relied heavily on the provinces’ wealth and, on the other hand, its power there was being increasingly contested. The region was also problematic from the perspective of the Habsburgs’ internal family politics: after Charles's abdication, the Low Countries found themselves under the government of the Spanish branch of the dynasty, but their proximity to the Holy Roman Empire made them of particular interest to the Austrian branch of the dynasty. All this made itself felt in the dynasty's use of its iconographic apparatus in the Low Countries, where political culture relied heavily on symbolic means.Footnote 61 Scipio Africanus—a powerful image already enshrined in the dynasty's symbolic repertoires—became a part of these conversations.

The first among Charles's descendants to cultivate the association between himself and Scipio was Charles's heir apparent, the future Philip II of Spain (1527–98), who evoked Scipio during his festive progress through the Low Countries between 1548 and 1549. The visit was organized to present Philip as Charles's successor with a view toward smoothing over the transition of power in the future. The prospects of Philip's succession posed difficulties for the Habsburgs, mainly because the prince, who was a staunch Catholic and unfamiliar with local customs, was not particularly popular in the Low Countries. Because his succession there was likely to be resisted, the dynasty employed a range of symbolic means at its disposal to promote his succession. Among these symbolic instruments, the Joyous Entry played a special role: a part of the festival tradition of medieval and early modern Europe, it was not merely a celebration, but rather a political act—an agreement between the city and the ruler.Footnote 62

It is significant therefore that Scipio Africanus was evoked during the Joyous Entries that punctuated Charles and Philip's progress through the provinces. Until then, Scipio had been primarily associated with Charles. However, the designs of the entry to Lille—one of the cities visited during the progress—shied away from drawing associations between the two: they depicted Charles's victories in Africa, but eschewed references to Scipio, which had previously accompanied the depictions of Charles's deeds in Italy.Footnote 63 Instead, the entry focused on drawing links between Scipio and Philip. During the progress, Philip visited the temple of virtue and honor, which was filled with individuals who exhibited such qualities; Scipio was depicted there alongside the Habsburgs’ real and imagined ancestors.Footnote 64 The subsequent entry to Antwerp appeared to return to the earlier associations between Charles and Scipio; it seemingly referenced the story of Scipio and his younger brother Lucius Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus (3rd century BC–after 183 BC) to tell the story of Habsburg succession. Scipio Asiaticus initially served under his older brother and subsequently achieved prominence for his victories in Asia, for which he was welcomed to Rome in a triumph. The designs of the entry appeared to refer to this story in that they declared that Philip would build on his father's success in Africa by expanding the Habsburgs’ power in Asia.Footnote 65

The associations between Philip and Scipio Africanus continued to be drawn at less formal stages of the progress, such as the celebrations at Binche. These festivities were special, because Philip, though accompanied by members of the dynasty like during the Joyous Entries, was presented exclusively to the nobility during tournaments, combats, banquets, and a masque.Footnote 66 On the last day of the festivities, after the final tournament and ball, the participants gathered in the Salle Enchantée, which was a space that featured a range of atmospheric effects and inventions. Among them was a structure of descending tables which presented delicacies to the audiences. It was towered with a baldachin-like structure decorated with the letter ‘P’ for Philip, which, depending on the lighting behind the mirrors, was illuminated against a dark background or appeared dark against an illuminated background. On the wall behind this construction “a magnificent tapestry in which the victories and conquest of Scipio Africanus unfolded” was displayed, as recounted by the official chronicler; it depicted the spoils being carried away by soldiers and lictors.Footnote 67 By employing this imagery, these celebrations juxtaposed Philip’s triumph in the tournaments held at Binche with Scipio's triumph following his conquest of Africa.

Philip's employment of the image of Scipio Africanus marked a clear continuation of the way in which this Roman hero functioned in the symbolic repertoires of his father in that the focus was placed principally on the military prowess of the Roman hero and his namesakes. Philip's iconographic apparatus recounted Scipio as a triumphant military leader rather than a virtuous ruler. Philip's uses of Scipio, however, varied from those of his father vis-à-vis some of the dynasty's rivals. The French royal family, who remained the Habsburgs’ main rival among Christian powers, continued to harbor their own associations with this Roman hero. Though previously the uses of Scipio by Charles V and Francis I constituted an expression of an ongoing conflict between the Habsburgs and the Valois, in the age of Philip the image of the Roman hero was used to communicate a changing relationship between the two dynasties. In 1559, Spain and France signed the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis, ending decades of wars in Italy; under the provisions of the treaty, Philip was to marry Elizabeth of Valois (1545–68), the eldest daughter of Henry II of France (1519–59), and Catherine de Medici (1519–89). The marriage ceremonies marking the union of the two dynasties were adorned with the tapestries of Scipio.Footnote 68 Considering the earlier use of Scipio by the two dynasties, this choice appears to have been intentional. However, the way in which it was used signified a shift in meaning; by evoking the dynasties’ shared claims to Scipio during ceremonies that marked the union of the two families, Scipio signified conciliation rather than rivalry. In the decade that followed, the image of Scipio continued to accompany meetings between the Habsburgs and the Valois. It was used again at their meeting at Bayonne in 1565. The tapestry depicting the triumph of Scipio decorated the French royal box on the first day of the festivities. It has been suggested that the use of the tapestry was indicative of Charles IX's (1550–74) desire to position himself—in the manner reminiscent of the relationship between Charles V and Francis I—as Philip's rival.Footnote 69 However, considering Philip's absence from the festival, the fact that the tapestry was not particularly prominent and instead displayed together with many other pieces, and the context of the meeting, which the French saw as an opportunity to secure a Spanish match for Charles's youngest sister, his use of Scipio might be more fittingly seen as an expression of a general desire to bolster the position of a fifteen-year-old ruler rather than a direct attack on Philip.

Rather unexpectedly, though, the most significant challenge to Philip's association with Scipio came from within the Habsburg dynasty. Philip did not hold a monopoly over the image of Scipio Africanus and the Roman hero proved appealing to other members of the dynasty. Thirty years after Philip's progress through the Low Countries, the image was adopted by Charles's grandson and Philip's nephew, Archduke Matthias. Though invested in the provinces’ affairs, the Austrian Habsburgs remained cautious about the extent of their involvement, wary not to step on the toes of their Spanish cousins.Footnote 70 This changed when in 1577, Philip's appointed representative Don Juan of Austria (1547–78) was deposed as Governor-General by the government of the provinces and a coalition of Catholic nobles arranged for the son of the late Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II (1527–76), Archduke Matthias of the Austrian branch of the dynasty, to assume the post. Though his appointment was objected to by both branches of the Habsburg dynasty, Matthias decided to accept the offer with the view of advancing his position and bringing the crisis in the provinces to an end.

During Matthias's governorship, Scipio Africanus became one of the key elements in his symbolic repertoires. Matthias first identified with this Roman hero during the Joyous Entry to Brussels in 1578, which marked the Archduke's official appointment as Governor-General. An illustrated account of the festival, published by Plantin in Antwerp a year later, popularized this association.Footnote 71 And so did the objects subsequently commissioned and acquired by the Archduke. Matthias's evoking of Scipio could be seen as an attempt to highlight his links to the dynasty; considering the Habsburgs’ refusal to support his appointment, stressing his dynastic association was particularly significant for the Archduke. In identifying with Scipio, Matthias thus continued a tradition which began with his great-grandfather, Archduke Philip, and was followed by his male successors in the provinces, all of whom fostered associations with this Roman hero.

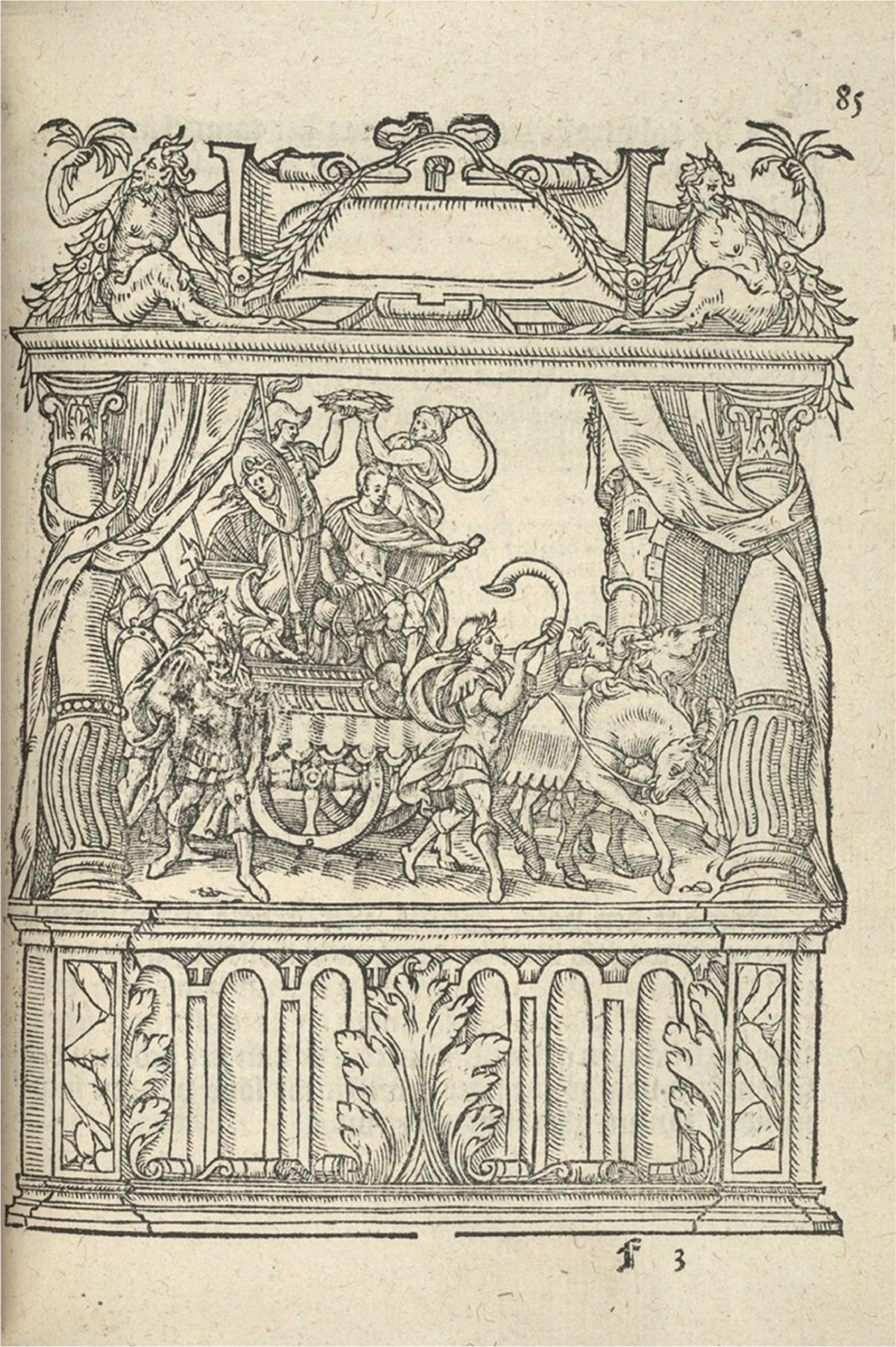

Yet, while Matthias drew from the Habsburgs’ earlier associations with Scipio Africanus to assert his authority, the way in which he embraced this Roman hero challenged the Spanish branch of the dynasty—the 1578 Joyous Entry offers a telling illustration. The festival depicted Matthias as Scipio and, as the author of the published account of the entry explained, the Archduke's mission as the “new Scipio” was to “free [the provinces] from that highly unjust and unbearable oppression of Don Juan and his adherents and also to maintain [the inhabitants of the Low Countries] in [their] liberties, rights and privileges, which [they had] received from [their] ancestors.”Footnote 72 Matthias's progress through the city was accompanied by six stages on which scenes from the hero's life were performed, offering a commentary on the situation in the provinces and the expectations that their inhabitants had of the Archduke. The first three stages included illustrations, both historical and symbolic of Scipio's virtue and commitment to the state, which were contrasted with the vices of the Senate; they included depictions of Scipio, Wisdom, and Philosophy (figure 4), Scipio confronting senators with a naked sword (figure 5), and senators, Scipio, Virtue, Wisdom, and Avarice (figure 6). Scipio's confronting of avarice, in particular, offered a telling reference to the situation in the provinces; together with religious persecutions, the economic exploitation of the provinces by the Spanish was the driving force behind the outbreak of the Dutch Revolt.Footnote 73 By identifying Matthias with Scipio, these scenes sought to present him as capable of addressing the abuses perpetuated by other members of his dynasty. Matthias's expected success was epitomized in the next three scenes. Tellingly, they included two distinct representations of Scipio’s victory—historical and symbolic. The image of Scipio defeating Hannibal (figure 7) was followed by a depiction of Scipio standing over the personifications of tyranny (figure 8), which in the discourse of the Dutch Revolt was traditionally identified with the Spanish.Footnote 74 Finally, Scipio was depicted in a triumphant progress (figure 9); he was portrayed holding a shield with the head of Medusa on it, which in the earlier scene represented tyranny, thus reiterating the anti-Spanish sentiments of the entry.

Figure 4. Maartin de Vos, Scipio, Wisdom, and Philosophy in Jan Baptista Houwaert, Sommare beschrijuinghe va[n]de triumphelijcke incomst vanden doorluchtighen ende hooghgheboren aeerts-hertoge Matthias: binnen die princelijcke stadt van Brussele: in t'iaer ons Heeren M.D.L.XXVIII (Antwerp, 1579) © British Library Board, 9930.d.11, fol. 70.

Figure 5. Maartin de Vos, Senators and Scipio with a naked sword in Jan Baptista Houwaert, Sommare beschrijuinghe va[n]de triumphelijcke incomst vanden doorluchtighen ende hooghgheboren aeerts-hertoge Matthias: binnen die princelijcke stadt van Brussele: in t'iaer ons Heeren M.D.L.XXVIII (Antwerp, 1579) © British Library Board, 9930.d.11, fol. 73.

Figure 6. Maartin de Vos, Senators, Scipio, Virtue, Wisdom, and Avarice in Jan Baptista Houwaert, Sommare beschrijuinghe va[n]de triumphelijcke incomst vanden doorluchtighen ende hooghgheboren aeerts-hertoge Matthias: binnen die princelijcke stadt van Brussele: in t'iaer ons Heeren M.D.L.XXVIII (Antwerp, 1579) © British Library Board, 9930.d.11, fol. 76.

Figure 7. Maartin de Vos, Hannibal and Scipio in Jan Baptista Houwaert, Sommare beschrijuinghe va[n]de triumphelijcke incomst vanden doorluchtighen ende hooghgheboren aeerts-hertoge Matthias: binnen die princelijcke stadt van Brussele: in t'iaer ons Heeren M.D.L.XXVIII (Antwerp, 1579) © British Library Board, 9930.d.11, fol. 79.

Figure 8. Maartin de Vos, Scipio and Tyranny in Jan Baptista Houwaert, Sommare beschrijuinghe va[n]de triumphelijcke incomst vanden doorluchtighen ende hooghgheboren aeerts-hertoge Matthias: binnen die princelijcke stadt van Brussele: in t'iaer ons Heeren M.D.L.XXVIII (Antwerp, 1579) © British Library Board, 9930.d.11, fol. 82.

Figure 9. Maartin de Vos, Senators, The Triumph of Scipio in Jan Baptista Houwaert, Sommare beschrijuinghe va[n]de triumphelijcke incomst vanden doorluchtighen ende hooghgheboren aeerts-hertoge Matthias: binnen die princelijcke stadt van Brussele: in t'iaer ons Heeren M.D.L.XXVIII (Antwerp, 1579) © British Library Board, 9930.d.11, fol. 85.

While the festival offered a general critique of the Spanish government in the provinces, Matthias's identification with Scipio appeared to target Philip personally. Matthias could have selected a different figure to emulate. Another ancient hero—Perseus—who defeated Medusa and liberated Andromeda from a sea serpent might have been a more obvious choice. By evoking the figure of Medusa in the Joyous Entry, Matthias already referenced the story of Perseus, which presented an equally suitable metaphor for the situation in the provinces. It also offered an additional advantage: because of Philip's lack of association with that Roman hero, it did not target Philip in such an overt way as Matthias's identification with Scipio Africanus. Indeed, the Archduke's identification with Scipio positioned him as Philip’s challenger rather than dynastic representative; it was reminiscent less of Philip’s adoption of this hero during his festive progress in 1548–49, and more of Charles’s bitter rivalry with Francis.

Matthias's use of Scipio Africanus—unusual for a member of the dynasty that was known for its unity and distinct identity—thus naturally raises questions of the extent to which it was an intentional choice on the Archduke's part. Traditionally, Matthias was thought to have exercised little power in the Low Countries. “Matthias can do nothing,” summed up Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle, a Dutch politician and clergyman, supporter of the Spanish, and an avid observer of the events.Footnote 75 Therefore, Matthias's entry to Brussels could have been passed off as a work of Brussels's rebellious magistrates. After all, these occasions were traditionally a point of bargaining between the ruler, the city, and the province: on the one hand, the Joyous Entry presented an opportunity for the ruler to assert his authority, and, on the other, it allowed the hosts to communicate their demands.Footnote 76 Matthias's position in the Low Countries was much weaker than that of his predecessors. It is reasonable to assume therefore that Matthias did not have as much influence on the shape of the festivities as some of his predecessors did. Even if that was the case, though, Matthias's engagement with these designs following the official entry suggests that he did not oppose the message promoted by his Joyous Entry. Not only did the Archduke later employ Lucas van Valckenborch, who had been the designer of the entry, as his court painter, but only a year after making the entry to Brussels, Matthias also commissioned Valckenborch to produce a painting that portrayed him as Scipio Africanus (figure 1). It departed from his earlier portraits which depicted Matthias in armor or courtly attire. Tellingly, the portrait, much like the 1579 entry evoked the themes of oppression and liberty; in the background, Matthias is depicted freeing prisoners, while in the foreground, the shield held by his soldier depicts Perseus liberating Andromeda. Matthias's choice to perpetuate his identification with Scipio Africanus beyond the context of the entry thus offers a telling indication that his use of the image of Scipio was a conscious choice.Footnote 77

The way in which Matthias continued to identify with Scipio Africanus beyond his stay in the Low Countries is also indicative of the Archduke's personal affinity with the ancient hero. By 1581, Matthias had abdicated his appointment in the Low Countries, before returning, disgraced and mistrusted by the family, to the Habsburg hereditary lands in Central Europe. Matthias brought with him printed editions of the account of his Joyous Entry into Brussels, which fostered his identification with Scipio Africanus. Meanwhile, the portrait of Matthias as Scipio was displayed at his courts in Linz and Vienna. But these were not the only objects linking Matthias to the ancient hero. The inventory of Matthias's possessions compiled after his death in 1619 listed “an agate with Scipio drawn in gold.” The agate bore the Latin inscription: “ungrateful fatherland, you won't have my bones”—a variation of the quote attributed to Scipio Africanus, who, after his voluntary exile from Rome, wished to have it written on his tombstone.Footnote 78 Though the object cannot be dated with much precision, it is likely that Matthias, eager to stress the parallels between himself and the Roman hero, commissioned it around the time of his voluntary departure from the Low Countries. Similar sentiments of toil and ingratitude encapsulated by the quote were voiced by Matthias and his circle at the time regarding his involvement in the Low Countries. In response to his family's criticism, Matthias declared: “despite the highest threat and inconvenience, I have worked only for the maintenance of our Catholic religion, the wellbeing of our honored House of Austria, and the liberation of the oppressed lands.”Footnote 79 Meanwhile, one of his confidants, Reichard Strein von Schwarzenau (1538–1600), consoled the Archduke, admitting that Matthias could “hope for little thanks” for his involvement in the Low Countries.Footnote 80

Matthias's use of Scipio Africanus constituted an important moment in the history of the dynasty's symbolic repertoires. This clash between Matthias and Philip shed light on the intellectual pluralism that underpinned the dynasty's symbolic repertoires, as the two princes deployed two distinct interpretations of Scipio. While Philip's Scipio followed the version formulated by Charles and was seen principally a conqueror, celebrated for his military triumphs, Matthias relied primarily on the understanding of this hero that aligned with the earlier version associated with Archduke Philip. Matthias's Scipio was celebrated as a man of virtue, a wise leader. Even when depicted as a military man, Matthias's Scipio was still first and foremost a man of virtue: Scipio was not a conqueror, but a defender of his people against tyranny. Crucially, however, Matthias's uses of Scipio revealed how the dynasty's iconographic apparatus could be deployed against other members of the dynasty.

It might have very well been because of Matthias's problematic use of this Roman hero that by the seventeenth century, Scipio had taken a back seat in the dynasty's symbolic repertoires. The Habsburgs were eager to display the Tunis tapestries, which once helped position Charles as the next Scipio.Footnote 81 Objects relating to Scipio, too, continued to circulate among the Habsburgs. Archduke Albert and Infanta Isabella bought two set of tapestries depicting the life of Scipio between 1607 and 1611.Footnote 82 Meanwhile, in the Austrian branch of the dynasty, a shield commemorating Charles V's identification with Scipio was acquired by the future Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II (1578–1637) in 1606.Footnote 83 But by this time, members of the Habsburg dynasty eschewed personal identifications with Scipio Africanus. For instance, in 1594, the entries to Antwerp and Brussels made by Matthias's older brother, Archduke Ernest (1553–95), who was appointed the Governor-General of the Low Countries, evoked the dynasty's conquests in Africa, but refrained from drawing direct comparisons between Ernest and Scipio.Footnote 84 And so did the subsequent Joyous Entries made by Matthias's younger brother, Archduke Albert (1559–1621) and his wife, Infanta Isabella (1556–1633).

It was not until the seventeenth century that Scipio Africanus was again evoked so publicly by the Habsburgs. The one to do so in this instance was Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand of Austria (1609–41). The younger brother of Philip IV of Spain (1605–65) and a successful military commander in the Thirty Years’ War, Ferdinand was appointed Governor-General of the Spanish Netherlands. His appointment was celebrated during his Joyous Entry to Ghent in 1635. Accounts of the festival, which included illustrations of the arches designed for the entry by Jacob Francart (ca. 1582–1651), were subsequently published in the Low Countries.Footnote 85

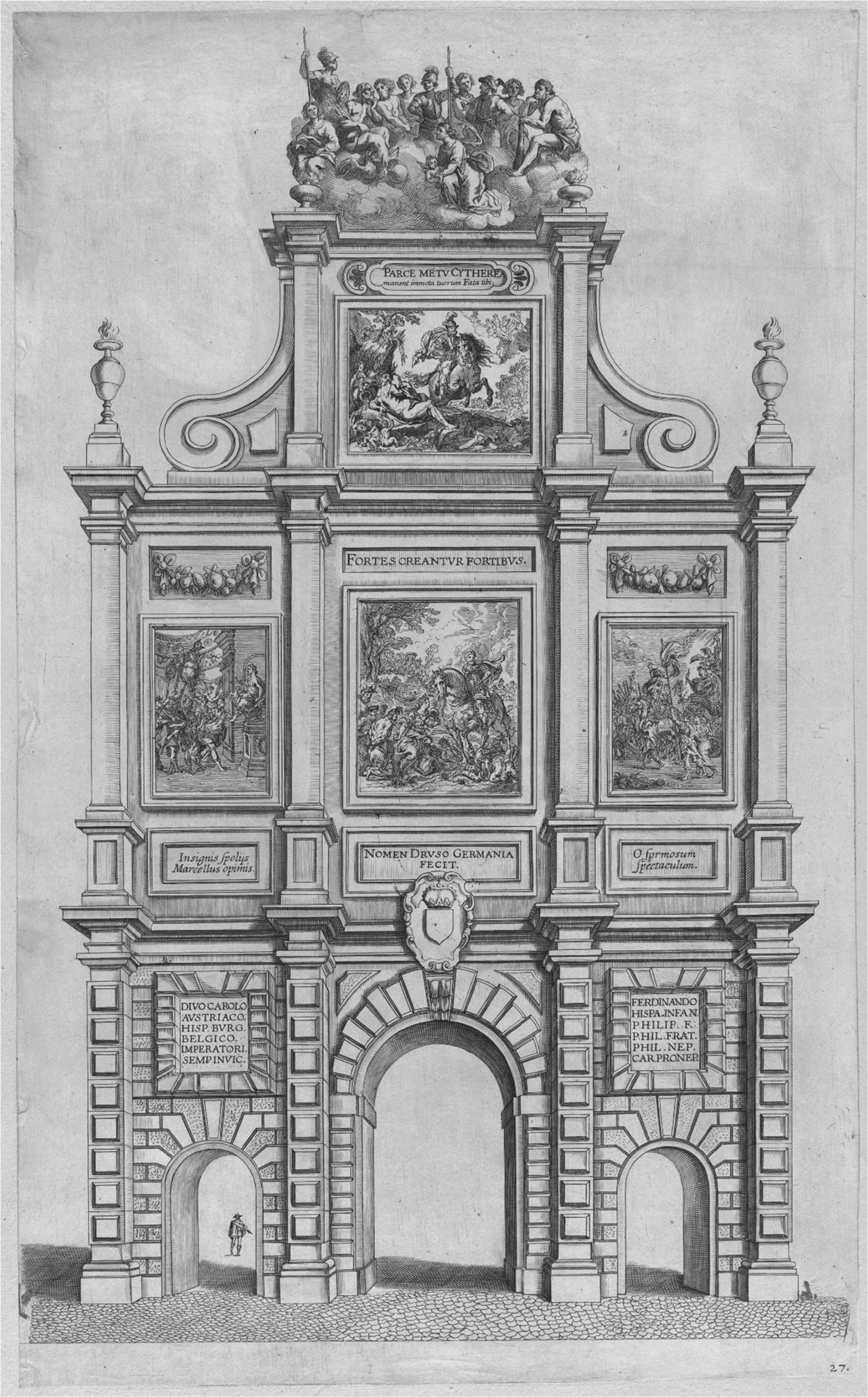

It was on the occasion of the entry to Ghent that Ferdinand decided to evoke the dynasty's association with Scipio Africanus. The Roman hero was depicted already on the second arch of the festival (figure 10). The front side of the arch was topped with a depiction of Ferdinand and his predecessors—Charles V, Philip II, Philip III, Isabella, and Philip IV—who were passing the baton to the new Governor-General (figure 11).Footnote 86 Among them, Charles was presented as the more important example of rulership for Ferdinand; the two were depicted below in an equestrian portrait and, according to the caption, Ferdinand was destined to inherit Charles's courage. The paintings below depicted examples of Charles's courage: the image of Charles receiving tribute from the defeated Schmalkaldic League was flanked by depictions of his success against Francis I in the battle of Pavia and his conquest of Tunis. These illustrations were juxtaposed with depictions of examples of courage from the antiquity, which adorned the rear of the arch (figure 12). In the place of Charles and Ferdinand's portrait was a painting of Romulus, whereas the depiction of Charles receiving the tribute from the defeated Schmalkaldic League was replaced with a depiction of Drusus Germanicus subduing the barbarian tribes. Charles's victory in the battle of Pavia was juxtaposed with Marcus Claudius Marcellus delivering spolia omnia following his defeat of a Gaulish leader in single combat. The image of Scipio Africanus in a chariot celebrating his triumph following his conquest of Carthage replaced Charles's conquest of Tunis.

Figure 10. Jacob Neeffs, The Triumph of Scipio Africanus, from Guilielmus Becanus, Serenissimi principis Ferdinandi Hispaniarum Infantis S.R.E. cardinalis introitus in Flandriae metropolim gandavum (Antwerp, 1636), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 51.501.7430. © Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1951.

Figure 11. Triumphal arch (elevation of the front), from Guilielmus Becanus, Serenissimi principis Ferdinandi Hispaniarum Infantis S.R.E. cardinalis introitus in Flandriae metropolim gandavum (Antwerp, 1636), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 51.501.7419, Plate 19. © Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1951.

Figure 12. Triumphal arch (elevation of the back), from Guilielmus Becanus, Serenissimi principis Ferdinandi Hispaniarum Infantis S.R.E. cardinalis introitus in Flandriae metropolim gandavum (Antwerp, 1636), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 51.501.7426, Plate 27. © Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1951.

Scipio Africanus functioned in the designs of the entry in two principal ways. On the one hand, Scipio complimented the commemorative character of the arch. The festival not only took place in the city of Charles's birth, but it also coincided with the one hundredth anniversary of his conquest of Tunis. By evoking comparisons between Charles and Scipio, the arch revivified a prominent theme from Charles’s symbolic repertoires. In doing so, it ultimately revived the interpretation of Scipio as a man of military prowess. On the other hand, the way in which Scipio Africanus, together with other ancient heroes, was depicted on the arch, was illustrative of how the dynasty conceptualized its power. This arch embodied the Habsburgs’ conviction that they were the rightful heirs to ancient Rome. By juxtaposing scenes from ancient history with those from Charles's life, the arch drew parallels between his accomplishments and those of ancient heroes. Meanwhile, the textual layer of the arch conveyed the ideas of inheritance; as the front of the arch proclaimed Charles's courage, the rear of the arch traced its origins to antiquity, by evoking Horace's verse: “brave spring from the brave.” Charles's courage thus appeared to spring from ancient heroes; Ferdinand's courage, which he was to learn from Charles, thus could be traced to the heroes of the past, including Scipio Africanus. While other ancient heroes depicted on the arch, such as Romulus and Drusus Germanicus were counted among the Habsburgs’ ancestors, Scipio was not. Scipio's inclusion in the design of the arch, alongside the dynasty's presumed ancestors, was thus revealing of his significance in the Habsburgs’ symbolic repertoires.

Conclusion

The story of Scipio Africanus was one of the most popular narrative cycles in early modern Europe, appearing under a variety of guises and in different contexts. Yet, for the Habsburgs, it acquired a special—dynastic—significance. While certain members of the dynasty came to identify with this Roman hero, others supported these efforts by acquiring and sponsoring objects that fostered such connections. In a way, the image of Scipio was used by the Habsburgs, much like other images comprising their symbolic repertoires, to elevate their position and claim the virtue, merit, and accomplishment that were associated with Scipio for members of the dynasty and their achievements. Crucially, however, Scipio's role in the dynasty's symbolic repertoires went beyond that and aided the Habsburgs in more nuanced ways; the Habsburgs employed the story of Scipio to assert their position, claim superiority over their rivals, make peace, and communicate transitions of power. The Habsburgs’ reliance on Scipio thus offers indications of how the dynasty conceptualized its power in early modern Europe. Scholars have so far stressed the significance of the dynasty's relationship with individuals from antiquity, both historical and fictional, in the context of the Habsburgs’ genealogical enterprise. By tracing their lineage to ancient rulers, gods, and heroes, the Habsburgs sought to position themselves as the heirs of ancient Rome. The dynasty's particular attachment to Scipio Africanus is significant because this Roman hero was not traditionally counted among the Habsburgs’ ancestors. His popularity and prominence in the dynasty's symbolic repertoires thus suggests a more complex understanding of how the Habsburgs drew from the heritage of antiquity. The Habsburgs’ consistent efforts to reference and identify with Scipio Africanus, his virtues and achievements, and their choice to display Scipio alongside their real and imagined ancestors, corroborate Larry Silver's suggestion that the Habsburgs’ sought to establish themselves as the heirs to the empire not only through blood links and descent of genealogy, but also through election and succession.Footnote 87 The dynasty's uses of Scipio may thus prompt us to consider other characters, both historical and fictional, who comprised the Habsburgs’ symbolic repertoires, but who were not traditionally counted among their ancestors.

The dynasty's uses of Scipio Africanus offer a lens through which to consider how the Habsburgs and those whom they governed conceived of their election and succession. The initial associations between the Habsburgs and this Roman hero centered upon the image of Scipio as a virtuous ruler, who was able to moderate his own appetites for the benefit of his people and the commonwealth. However, this was not the only interpretation of Scipio that was deployed by the Habsburgs in the early modern period. Another image of this Roman hero formulated by the dynasty centered upon Scipio's military prowess. Scipio Africanus was not merely a stock image of virtue, merit, and accomplishment, at least not in simple terms; the ways in which the Habsburgs fluctuated between these different interpretations of Scipio were revealing of their aspirations, struggles, strengths, vulnerabilities, and identities. This is also revealing of the nature of the dynasty and its symbolic repertoires in an important period in its history. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Habsburgs went through a dramatic transformation—the dynasty rapidly spread across the continent to become one of the greatest royal houses in the early modern world. As the dynasty expanded, it also became fragmented, which made it increasingly challenging for the Habsburgs to preserve their internal unity and uniformity.Footnote 88 The Habsburgs’ symbolic repertoires, through which they communicated their dynastic ideology, remained, it has been argued, a unifying force for the dynasty and its diverse lands, providing a degree of uniformity to the polyglot family scattered across Europe. The Habsburgs’ uses of Scipio, however, offer a reminder that the dynasty's ideological uniformity at that time ought not to be taken for granted. While Archduke Matthias's involvement in the Low Countries against the wishes of his family demonstrated that the Habsburgs were not immune to internal conflicts, his uses of Scipio Africanus during his time in the provinces reveal how the Habsburgs could easily weaponize the images comprising the dynasty's symbolic repertoires against each other. The Habsburgs’ reliance on shared symbolic repertoires thus presented a significant advantage, but it also rendered them uniquely vulnerable.