Heracleion and Canopus were towns recorded in Classical sources about the Nile delta. Surveys near Alexandria in 1996 found ruins poking through the sands under four or five fathoms of murky water. Revealing complexes of temples, excavation then confirmed that these were the remains of Heracleion and the eastern part of Canopus, dating from the Late Dynastic era. The discoveries show how Greek traders had settled, and how the towns then thrived, after Alexander the Great's conquest (332 BC), during the Hellenistic or Ptolemaic period. Following a somewhat smaller display in Paris in 2015–2016, many of the finds can now be admired at the British Museum until 27 November 2016 in the exhibition ‘Sunken cities: Egypt's lost worlds’.

The exhibition's opening, in May 2016, was inauspicious. Greenpeace staged a spectacular demonstration against BP's sponsorship, arguing that tides are rising today as a consequence of burning oil. BP has supported the Museum for 20 years, and the publicity names ‘Sunken cities’ ‘The BP exhibition’. Among other exhibitions, the corporation sponsored ‘Vikings’ and ‘Hadrian’ too. Nor was Greenpeace's the first such demonstration. BP has even been accused of influencing the content of one exhibition in 2015 (Kendall Reference Kendall2016). Yet the early indications were that ‘Sunken cities’ would prove very popular.

BP's chief suggests that, in exploring depths for assets, the firm works like the archaeologists (Goddio & Masson-Berghoff Reference Goddio and Masson-Berghoff2016: 10). The exhibition's first heading, “Treasures. . .and masterpieces”, is equally vapid. The prevailing impression from what follows is of statues and stelae looming through a bluish light, the galleries suffused with suspenseful ‘mood’ music and the occasional splash of an oar or flipper. The central display is an impressive example of the Museum's tradition of presenting Egyptian antiquities (Moser Reference Moser2006: 79, 221–23). Statues of a king and queen stand there, 5 metres high, in Dynastic art's familiar formal posture. They preside over a massive wooden carving of the god Serapis, a life-size sculpture of Apis, the sacred bull, three little masonry shrines, a sphinx and, in the foreground, the headless statue of Queen Arsinoë II. Then, from the side of the gallery, the Apis appears to gaze out at one of the little shrines, the wooden Serapis and two other busts of that god suspended in the gloaming. Does ‘Sunken cities’ just indulge, then, in the alluring popular image of ancient Egypt that the Museum itself has done so much to create (Moser Reference Moser2006)?

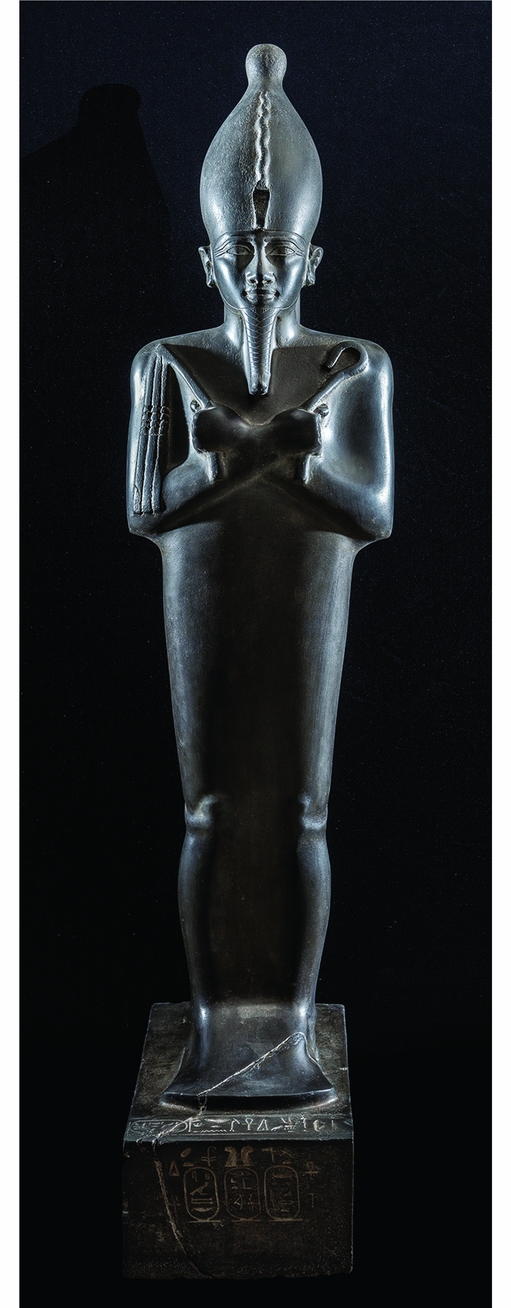

To the contrary, the exhibition can be enjoyed at different pitches of concentration. There is a lot of intriguing detail, lit superbly. Orthodox posture notwithstanding, Arsinoë’s sensuous front is quite alien to the ancient Egyptian tradition of statuary. In front of her glint five tiny gold coins. The naos (shrine) of the Decades, assembled with a last fragment recovered at Canopus in 1999, can now be studied almost intact. From Heracleion are the little Amun-Gereb shrine for royal legitimation, with ritual kit collected from around it, and two stelae. Visitors are captivated by several sculptures in greywacke (Figure 1). Worked carefully, this fabric yields a surface, smooth and lustrous but matte, that seems to swell with inner presence. So, shining dully, as though just emerged from the river, Tawaret, the hippopotamus goddess, looks portentous. There are very effective supplementary illustrations too: a big, bright impression of Heracleion's heyday and of how the town subsided beneath the river; several short sequences of film showing divers at work; and photography of a sunken barge in situ laid on the floor for a diver's view with films alongside showing the excavation and conservation of the timbers.

Figure 1. Greywacke Osiris, seventh century BC, from Medinet Habu (Luxor; 1.5m high; Christoph Gerigk © Franck Goddio/Hilti Foundation).

‘Sunken cities’ does not explain why so much has been lifted from the water. Nor, for want of details on the topography, does it justify the hackneyed epithet ‘cities’. Yet it does offer an interpretive theme, one very apt for London today and so many other places: the archaeology shows how the Greeks adjusted themselves to Egypt. It relies on the expressive evidence of worship, and, in a distinct pattern of lighting, contemporary and earlier finds from districts upriver help to illustrate the myth of Osiris as a basic feature of Egyptian cosmology long exploited in royal propaganda (Figure 1). For, on the archaeological evidence, the most obvious way by which the Greeks tried to settle in was their adoption of Egyptian ideology and style, seen not just in the statues of royalty and a towering personification of the Nile flood, or in the shrines, but also in ritual paraphernalia of gold, bronze, lead, faience and stone. The last group of displays explains how Antinous, the Roman Emperor Hadrian's lover, was drowned during the festival for Osiris, perhaps a deliberate sacrifice to Egyptian tradition. The exhibition suggests that there was syncretism too, albeit in decidedly Classical idiom: Dionysos and Serapis for Osiris, Herakles for Khonsu. With specimens both from Canopus and Heracleion, and, perhaps analogously, from Naukratis too, 100km upstream (Villing & Thomas Reference Villing and Thomas2016), the exhibition tries to distinguish ‘multiculturalism’; but that evidence and especially the design and surface treatments of several of the Roman pieces, quite unlike both the Egyptian material and most of the Greek, could just as well indicate either unreceptive colonisation or Egyptian assimilation to Classical style. With better information on the contexts at Canopus and Heracleion, visitors could have assessed the evidence for culture change more critically. Along with the finds from Naukratis, would comparison from the long history of Greeks in Alexandria be interesting too?

Most of the 297 exhibits were found by the divers, but, in addition to loans from Alexandria's Maritime Museum, ‘Sunken cities’ draws on three other collections in Egypt and two in England, as well as a big contribution from the British Museum's own holdings. The fine catalogue (Goddio & Masson-Berghoff Reference Goddio and Masson-Berghoff2016) has accounts of Heracleion and Canopus, three historical chapters and one discussing how the towns developed their rites for Osiris. There is also a small book based on the catalogue and an audio guide produced to the latest best standard.

Entry to ‘Sunken cities’ costs £16.50, the Museum's going rate for major temporary exhibitions. Supported by BP's rival, Total, Paris's version of the show, at the Institut du Monde Arabe, cost proportionately the same amount. Sponsors are now an essential prerequisite for large temporary exhibitions: a previous one at the British Museum, ‘Ice Age art’, in 2013, had been postponed pending sponsorship (H. Boulton pers. comm. 2011). With its remarks on Greenpeace (Kendall Reference Kendall2016), the Museums Association provided a link to recent ‘additional guidance’ for its code of ethics, admonishing museums “to conduct due diligence on. . .partners. . .to ensure. . .public trust” (Museums Association n.d.: 16). Or can the British Museum count on that whatever it does, much as perhaps it always counts on ancient Egypt to draw visitors?

Acknowledgements

Hannah Boulton, at the British Museum, courteously arranged for my visit and provided the figure. I benefited too from discussion with Susan Pattie and Simon Stoddart, and from the suggestions of Chris Scarre.