North Macedonia and the Neolithisation of South-eastern Europe

The current state of research suggests that the Neolithisation of South-eastern Europe started in Thessaly, after the arrival of early farmers from western Anatolia via maritime networks c. 6500 BC, and spread northwards, most likely along the Vardar River and the Pelagonia Valley (Naumov Reference Naumov2015; Krauss et al. Reference Krauß, Marinova, de Brue and Weninger2018). These early farmers often settled in villages that developed into tell sites. Archaeobotanical investigations have provided highly valuable information on the set of crops grown in different areas (e.g. Ivanova et al. Reference Ivanova, de Cupere, Ethier and Marinova2018; Gaastra et al. Reference Gaastra, de Vareilles and Vander Linden2019). The crop assemblages found in sites located in Thessaly and Thrace kept many similarities with those known from Anatolia. Conversely, a more reduced crop assemblage spread into the Balkans (e.g. Colledge & Conolly Reference Colledge, Conolly, Spataro and Biagi2007; Marinova et al. Reference Marinova, de Cupere, Nikolov, Bacvarov and Gleser2016; Marinova Reference Marinova, Lechterbeck and Fischer2017), with a more limited range of pulses, and also lacking some of the cereals such as naked barley (Hordeum vulgare var. nudum). Nevertheless, with the exception of Bulgaria (e.g. Kreuz & Marinova Reference Kreuz and Marinova2017), the state of research for these early phases is still precarious because of the paucity of evidence (Valamoti & Kotsakis Reference Valamoti, Kotsakis, Colledge and Conolly2007). Despite new research in the Korça Basin, Albania (Allen & Gjipali Reference Allen, Gjipali, Përzhita, Gjipali, Hoxha and Muka2014), the Struma Valley, Bulgaria (Marinova et al. Reference Marinova, de Cupere, Nikolov, Bacvarov and Gleser2016; Marinova Reference Marinova, Lechterbeck and Fischer2017), and the Pelagonia Valley (Beneš et al. Reference Beneš, Naumov, Majerovičová, Budilová, Bumerl, Komárková, Kovárník, Vychronová and Juřičková2018), we have limited knowledge of the nature of farming, domestic activities, refuse management and the overall role of cultivated and gathered plants in the Neolithic diet. Our project aims to understand these factors by applying micro-refuse and archaeobotanical analyses to Macedonian sites.

Two roughly contemporaneous sites located in the northern part of the Pelagonia Valley, in North Macedonia, are currently being investigated: Vrbjanska Čuka and Veluška Tumba (Figure 1). Vrbjanska Čuka is one of the biggest Early Neolithic tell sites in the valley with a surface area of around 2500m2, and both sites have stratigraphic deposits reaching 2–4m in height, with several building phases dated to c. 6000–5700 cal BC. Vrbjanska Čuka shows a remarkable preservation of floor levels, clay storage bins, grinding areas and hearths (Naumov et al. Reference Naumov, Mitkoski, Talevski, Fidanoski and Naumov2018a & Reference Naumovb) (Figure 2). The continental climate of the Pelagonia Valley makes these sites of particular interest for the Neolithisation process.

Figure 1. Map showing the location of the sites (map by G. Prats).

Figure 2. Area of the 2019 excavation at Vrbjanska Čuka, with the different buildings and associated features shown via colour-coding (photograph by Hristijan Talevski, edited by Goce Naumov).

Reconstructing ‘taskscapes’: a micro-refuse approach

The 2019 campaign allowed the testing of the methodology for the study of refuse management and indoor activities at Vrbjanska Čuka. This approach involves a systematic sampling of multiple contexts from each house (samples of 10 litres), wet-sieving of the samples with the wash-over technique (Steiner et al. Reference Steiner, Antolín and Jacomet2015), and sorting of all fractions (organic and inorganic or heavy fractions). For the analysis of the elements found in the different fractions, a micro-residue approach was applied (Ullah et al. Reference Ullah, Duffy and Banning2015). Over 30 variables, including any recognisable category preserved in the fractions (sand and daub fragments, calcined bone, tubers and the like), are quantified. The main aim is to identify patterns in the small-sized remains that would otherwise be hidden in the sediment and that reflect anthropogenic activity and may better show the spatial patterns of domestic tasks (e.g. areas of cereal processing, meat processing and refuse disposal).

Preliminary results from Vrbjanska Čuka

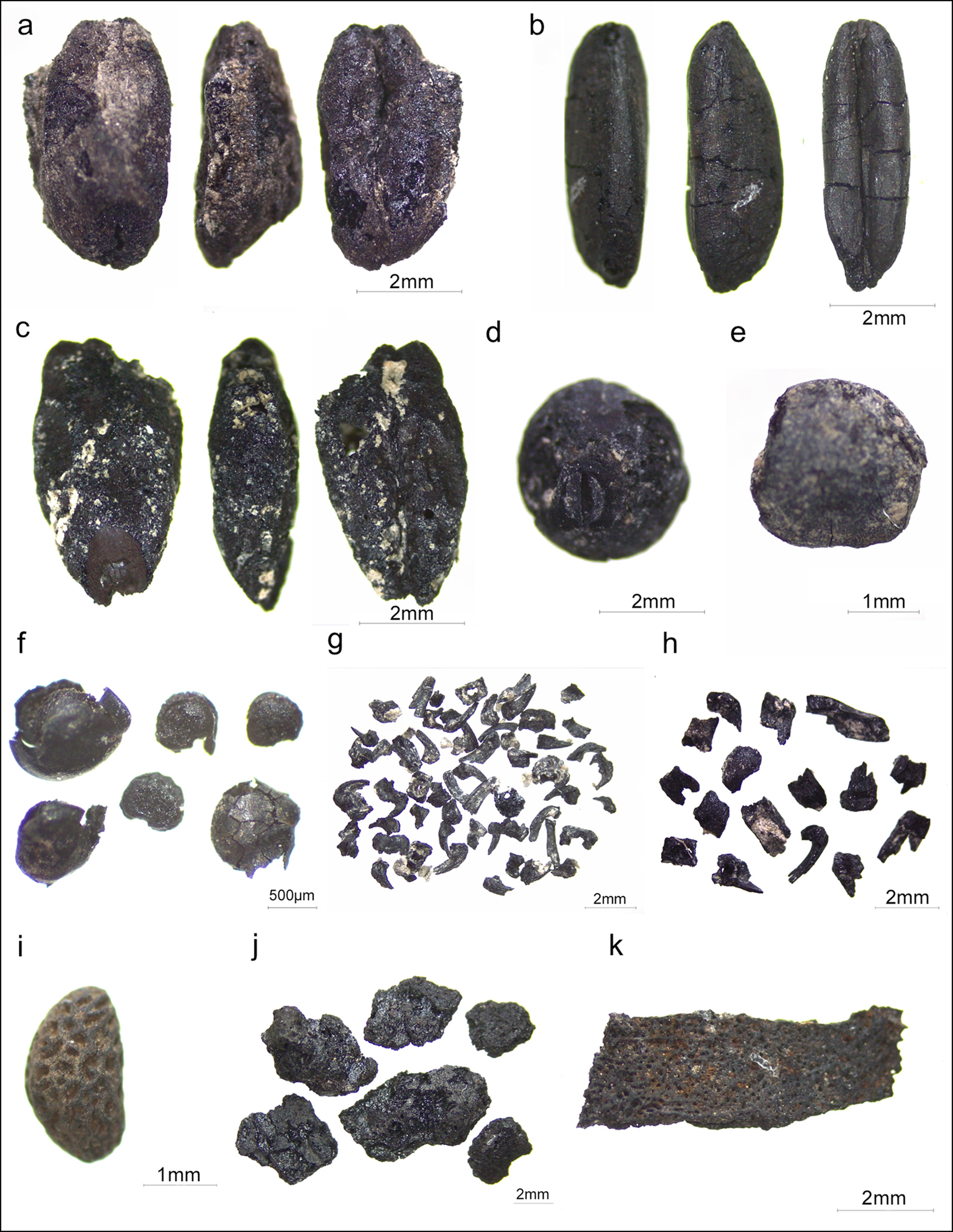

Four cereal crops and three pulses were documented at Vrbjanska Čuka; no oil plants have been discovered so far (Table 1 & Figure 3). The crop spectrum is similar to that known from sites in Greece, although naked wheat (Triticum aestivum/durum/turgidum) and new glume wheat (Triticum sp./new type) are absent. Gathered plants were found, including whole charred fruits, suggesting that gathering was an important activity, with harvested goods stored within the house.

Figure 3. Archaeobotanical remains found at Vrbjanska Čuka: a) emmer (Triticum dicoccum); b) 2-grained einkorn (T. monococcum); c) barley (Hordeum distichon/vulgare); d) pea (Pisum sativum); e) lentil (Lens culinaris); f) fat-hen (Chenopodium album); g) einkorn (Triticum monococcum) glume bases; h) emmer (Triticum dicoccum) glume bases; i) bramble (Rubus fruticosus); j) amorphous charred object (possible food remains); k) charred food crust (photographs by R. Soteras).

Table 1. Preliminary results of the 2019 campaign at Vrbjanska Čuka; only cultivars and gathered plants shown (Secale sp. and Setaria sp. finds excluded).

* These taxa are underrepresented in the table because the 0.35mm fraction has only been analysed in 13 of the 19 samples.

Preliminary results of the micro-refuse analysis indicate promising trends (Figure 4). Some of the observed patterns might be obvious, as is shown by sample 15, an in situ burnt posthole where only charcoal was found. Others are more significant, such as a sample coming from an oven (sample 18), where almost exclusively grains and chaff were recovered. Refuse deposits are characterised by a mixture of charcoal, seeds, chaff, bone fragments and potsherds (samples 21, 12 and 11). Sample 13 is indicative of consumption residues (calcined bones, fish remains and the like), while sample 10, with a dominance of chaff remains, might be the result of discarding the by-products of dehusking.

Figure 4. First results obtained from the micro-refuse analysis at Vrbjanska Čuka (graphs by F. Antolín).

Future perspectives

The investigation of additional sites in Pelagonia Valley and the Ohrid region is envisaged in order to understand better the Neolithisation process and the connections between these regions. Radiocarbon dating of all crop species will be essential to exclude contaminations from younger layers and to reconstruct house cycles.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Museum of Prilep and the Museum of Bitola.