Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 A Marginal Centrist: Tzvetan Todorov and the French Intellectual Field

- 2 Todorov and Camus

- 3 The Enlightenment Redux: Autonomy in Todorov, Glucksmann, and Onfray

- 4 Todorov's Reading of Rousseau: A Heritage for Our Times?

- 5 Tzvetan Todorov's Enlightenment

- 6 Todorov and Bakhtin

- 7 Tzvetan Todorov and the Writing of History

- 8 Tzvetan Todorov and the Trials of History: A Dissenting Voice

- 9 European Integration and the Cultural Cold War: Todorov and Denis de Rougemont

- 10 Tzvetan Todorov on Totalitarianism, Scientism, and Utopia

- 11 Tzvetan Todorov's Political Philosophy

- 12 Interview with Tzvetan Todorov

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

Introduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 26 April 2020

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 A Marginal Centrist: Tzvetan Todorov and the French Intellectual Field

- 2 Todorov and Camus

- 3 The Enlightenment Redux: Autonomy in Todorov, Glucksmann, and Onfray

- 4 Todorov's Reading of Rousseau: A Heritage for Our Times?

- 5 Tzvetan Todorov's Enlightenment

- 6 Todorov and Bakhtin

- 7 Tzvetan Todorov and the Writing of History

- 8 Tzvetan Todorov and the Trials of History: A Dissenting Voice

- 9 European Integration and the Cultural Cold War: Todorov and Denis de Rougemont

- 10 Tzvetan Todorov on Totalitarianism, Scientism, and Utopia

- 11 Tzvetan Todorov's Political Philosophy

- 12 Interview with Tzvetan Todorov

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

Summary

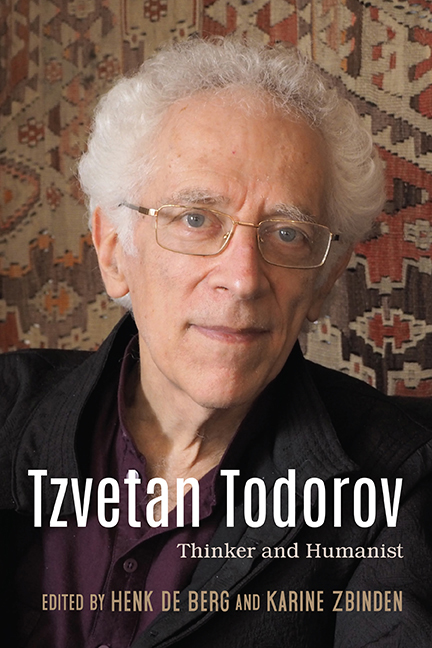

“TZVETAN TODOROV IS a skinny guy in glasses with an enormous mass of curly hair. He is also a linguistic researcher who has lived in France for twenty years, a disciple of Barthes who worked on literary genres (the fantastic, in particular), a specialist in rhetoric and semiotics… . Having grown up in a totalitarian country evidently aided the development of a very strong humanist conscience, which comes out even in his linguistic theories… . [He speaks] immaculate French but with a st ill very noticeable accent”: this is how Laurent Binet's novel La septieme fonction du langage (The Seventh Function of Language, 2015) describes the thinker who is the topic of our volume of essays. Binet's book, part literary fiction and part crime story, is set in 1980/81—the period when François Mitterra nd succeeded Valéry Giscard d’Estaing to the presidency—and features a range of famous philosophers and literary theorists, from Michel Foucault, Hélene Cixous, and Julia Kristeva to Jacques Derrida and Bernard-Henri Lévy. Tzvetan Todorov's presence among these luminaries is not accidental: he was undoubtedly one of France's most important and most respected intellectuals of the past fifty years. Yet Todorov plays only a minor role in the novel, and this is perhaps no coincidence either: although a thinker of the highest caliber, he never achieved the iconic status of a Foucault or—to name another Eastern Europe–born theorist—a Slavoj Žižek.

There are several reasons for this relative lack of fame. First, Todorov was always excessively modest about his work, and his self-e ffacing manner was directly at odds with the demands of our media age and its obsession with c elebrity. Though not a recluse and not afraid to express his opinion, he never sought the limeligh t and he engaged in few controversial debates. More over, w hen he expressed himself publicly, he did so with the same rhetorical restraint and intellectual fair-mindedness that a re characteristic of his academic work. This, it seems to us, is the second reason he never became one of the “stars” of the intelligentsia. European—and especially French—thought has a tendency toward binarism and extremism, be it of the left-wing or the right-wing variety.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Tzvetan TodorovThinker and Humanist, pp. 1 - 19Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2020