Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 “Schwimme mit mir hinüber zu den Hütten unserer Nachbarn”: Colonial Islands in Sophie von La Roche's Erscheinungen am See Oneida (1798) and Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre's Paul et Virginie (1788)

- 2 “Hier oder nirgends ist Amerika!”: America and the Idea of Autonomy in Sophie Mereau's “Elise” (1800)

- 3 A “Swiss Amazon” in the New World: Images of America in the Lebensbeschreibung of Regula Engel (1821)

- 4 Amalia Schoppe's Die Auswanderer nach Brasilien oder die Hütte am Gigitonhonha (1828)

- 5 Inscribed in the Body: Ida Pfeiffer's Reise in die neue Welt (1856)

- 6 Mathilde Franziska Anneke's Anti-Slavery Novella Uhland in Texas (1866)

- 7 “Ich bin ein Pioneer”: Sidonie Grünwald-Zerkowitz's Die Lieder der Mormonin (1887) and the Erotic Exploration of Exotic America

- 8 Seductive and Destructive: Argentina in Gabriele Reuter's Kolonistenvolk (1889)

- 9 Inventing America: German Racism and Colonial Dreams in Sophie Wörishöffer's Im Goldlande Kalifornien (1891)

- 10 Aus vergangenen Tagen: Eine Erzählung aus der Sklavenzeit (1906): Clara Berens's German American “Race Melodrama” in Its American Literary Contexts

- 11 “Der verfluchte Yankee!” Gabriele Reuter's Episode Hopkins (1889) and Der Amerikaner (1907)

- 12 Reframing the Poetics of the Aztec Empire: Gertrud Kolmar's “Die Aztekin” (1920)

- 13 Synthesis, Gender, and Race in Alice Salomon's Kultur im Werden (1924)

- 14 Land of Fantasy, Land of Fiction: Klara May's Mit Karl May durch Amerika (1931)

- 15 An Ideological Framing of Annemarie Schwarzenbach's Racialized Gaze: Writing and Shooting for the USA-Reportagen (1936–38)

- 16 “Fighting against Manitou”: German Identity and Ilse Schreiber' Canada Novels Die Schwestern aus Memel (1936) and Die Flucht in aradies (1939)

- 17 Mexico as a Model for How to Live in the Times of History: Anna Seghers's Crisanta (1951)

- 18 East Germany's Imaginary Indians: Liselotte Welskopf-Henrich's Harka Cycle (1951–63) and Its DEFA Adaptation Die Söhne der Großen Bärin (1966)

- 19 Finding Identity through Traveling the New World: Angela Krauß's Die Überfliegerin (1995) and Milliarden neuer Sterne (1999)

- 20 Discovery or Invention: Newfoundland in Gabrielle Alioth's Die Erfindung von Liebe und Tod (2003)

- 21 Tzveta Sofronieva's “Über das Glück nach der Lektüre von Schopenhauer, in Kalifornien” (2007)

- 22 “Amerika ist alles und das Gegenteil von allem. Amerika ist anders.” Milena Moser's Travel Guide to San Francisco (2008)

- Bibliography: The New World in German-Language Literature by Women

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

2 - “Hier oder nirgends ist Amerika!”: America and the Idea of Autonomy in Sophie Mereau's “Elise” (1800)

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 August 2014

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 “Schwimme mit mir hinüber zu den Hütten unserer Nachbarn”: Colonial Islands in Sophie von La Roche's Erscheinungen am See Oneida (1798) and Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre's Paul et Virginie (1788)

- 2 “Hier oder nirgends ist Amerika!”: America and the Idea of Autonomy in Sophie Mereau's “Elise” (1800)

- 3 A “Swiss Amazon” in the New World: Images of America in the Lebensbeschreibung of Regula Engel (1821)

- 4 Amalia Schoppe's Die Auswanderer nach Brasilien oder die Hütte am Gigitonhonha (1828)

- 5 Inscribed in the Body: Ida Pfeiffer's Reise in die neue Welt (1856)

- 6 Mathilde Franziska Anneke's Anti-Slavery Novella Uhland in Texas (1866)

- 7 “Ich bin ein Pioneer”: Sidonie Grünwald-Zerkowitz's Die Lieder der Mormonin (1887) and the Erotic Exploration of Exotic America

- 8 Seductive and Destructive: Argentina in Gabriele Reuter's Kolonistenvolk (1889)

- 9 Inventing America: German Racism and Colonial Dreams in Sophie Wörishöffer's Im Goldlande Kalifornien (1891)

- 10 Aus vergangenen Tagen: Eine Erzählung aus der Sklavenzeit (1906): Clara Berens's German American “Race Melodrama” in Its American Literary Contexts

- 11 “Der verfluchte Yankee!” Gabriele Reuter's Episode Hopkins (1889) and Der Amerikaner (1907)

- 12 Reframing the Poetics of the Aztec Empire: Gertrud Kolmar's “Die Aztekin” (1920)

- 13 Synthesis, Gender, and Race in Alice Salomon's Kultur im Werden (1924)

- 14 Land of Fantasy, Land of Fiction: Klara May's Mit Karl May durch Amerika (1931)

- 15 An Ideological Framing of Annemarie Schwarzenbach's Racialized Gaze: Writing and Shooting for the USA-Reportagen (1936–38)

- 16 “Fighting against Manitou”: German Identity and Ilse Schreiber' Canada Novels Die Schwestern aus Memel (1936) and Die Flucht in aradies (1939)

- 17 Mexico as a Model for How to Live in the Times of History: Anna Seghers's Crisanta (1951)

- 18 East Germany's Imaginary Indians: Liselotte Welskopf-Henrich's Harka Cycle (1951–63) and Its DEFA Adaptation Die Söhne der Großen Bärin (1966)

- 19 Finding Identity through Traveling the New World: Angela Krauß's Die Überfliegerin (1995) and Milliarden neuer Sterne (1999)

- 20 Discovery or Invention: Newfoundland in Gabrielle Alioth's Die Erfindung von Liebe und Tod (2003)

- 21 Tzveta Sofronieva's “Über das Glück nach der Lektüre von Schopenhauer, in Kalifornien” (2007)

- 22 “Amerika ist alles und das Gegenteil von allem. Amerika ist anders.” Milena Moser's Travel Guide to San Francisco (2008)

- Bibliography: The New World in German-Language Literature by Women

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

Summary

Born in 1770—the same year as Hölderlin and Hegel—Sophie Schubart married the very persistent librarian at the University of Jena, Karl Mereau, on 4 April 1793. He was not a poet, she told him she did not love him, but he continued to woo her on the merits of his colleagues. Schiller, Reinhold (soon to be replaced by Fichte), Goethe, Herder, and Wieland were all in Jena or nearby Weimar, and more talent soon followed: the Schlegels, Schelling, Novalis, Hölderlin, Jean Paul, Tieck. For an aspiring writer whose opportunities were limited by her sex, the temptation of such associations was too great. Mrs. Mereau came to Jena, quickly found a lover, published stories, poems, translations, and a novel, and gained notoriety as Fichte's one female auditor. After establishing herself as a social and literary figure, Sophie Mereau boldly, but with anguish, divorced her husband in 1801 and briefly lived off her income as a writer and editor, one of the first German women to do so. Finding herself pregnant by Clemens Brentano in 1803, she married him and then died giving birth to their third child in 1806. Her first husband, Karl, supported her as a writer, but she did not love him; her second, Clemens, opposed her writing and she loved him anyway—a contradiction symbolizing, perhaps, Mereau's conflicting instincts as an early modern woman.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

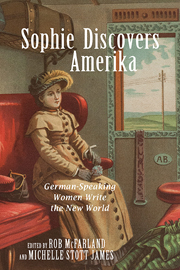

- Sophie Discovers AmerikaGerman-Speaking Women Write the New World, pp. 30 - 44Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2014