Inauguration and Liturgical Kingship in the Long Twelfth Century

Inauguration and Liturgical Kingship in the Long Twelfth Century Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Timeline

- Genealogies

- Introduction

- 1 Liturgical Texts: The Spoken Word and Song

- 2 Liturgical Rituals: Rubrication and Regalia

- 3 Who and Where? Actors, Location and Legitimacy

- 4 What and When? Consecration and the Liturgical Calendar

- 5 Royal Titles, Anniversaries and their Meaning: The Charter Evidence

- 6 Seal Impressions and Christomimetic Kingship

- Conclusion

- Appendix 1 Editions and Manuscripts of the Selected Ordines

- Appendix 2 Prayer Formulae Incipits

- Appendix 3 Tables of Ritual Elements in the Ordines

- Appendix 4 Brief Descriptions of Royal and Imperial Seals and Bullae

- Bibliography

- Index of Biblical References

- General Index

6 - Seal Impressions and Christomimetic Kingship

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 25 October 2019

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Timeline

- Genealogies

- Introduction

- 1 Liturgical Texts: The Spoken Word and Song

- 2 Liturgical Rituals: Rubrication and Regalia

- 3 Who and Where? Actors, Location and Legitimacy

- 4 What and When? Consecration and the Liturgical Calendar

- 5 Royal Titles, Anniversaries and their Meaning: The Charter Evidence

- 6 Seal Impressions and Christomimetic Kingship

- Conclusion

- Appendix 1 Editions and Manuscripts of the Selected Ordines

- Appendix 2 Prayer Formulae Incipits

- Appendix 3 Tables of Ritual Elements in the Ordines

- Appendix 4 Brief Descriptions of Royal and Imperial Seals and Bullae

- Bibliography

- Index of Biblical References

- General Index

Summary

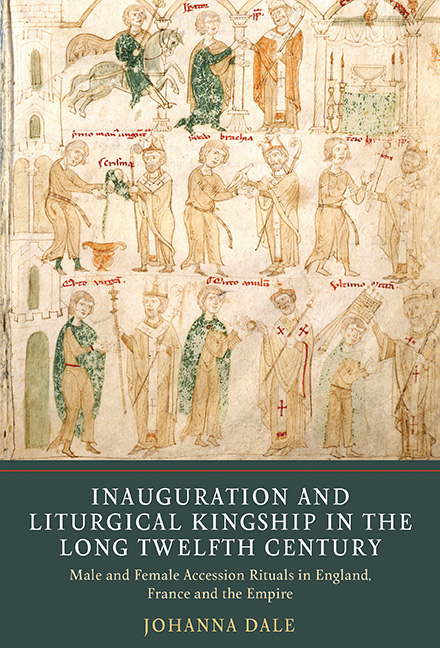

Eadmer describes Henry I's issuing of a ‘coronation charter’ in his Historia novorum in Anglia. He recounts that Henry made promises during his consecration and that he then ordered that ‘all these promises confirmed by a solemn oath [were] to be published throughout the kingdom with, by way of a lasting memorial, a written document authenticated by his seal in witness of its validity’. Henry's first seal was two-sided. The obverse depicted him enthroned, clasping items of regalia. On the reverse he was depicted on horseback carrying a banner and shield. By the mid-eleventh century English, French and German kings all used the image of an enthroned monarch on their great seals, and this image was to endure for the rest of the medieval period and beyond. Otto III had been the first Western ruler to be depicted on his seal enthroned in majesty thereby appropriating a previously exclusively religious image for royal purposes. Henry I in France adopted this innovation in 1031 and in England the first surviving royal seal, that of Edward the Confessor, features the enthroned design. That monarchs in all three realms utilized this iconography, in which they presented their kingship as imitating Christ's, is indicative of their shared liturgical and biblical vocabulary. This Christomimetic symbol, used only after consecration, was a visual expression of the transformation wrought by inauguration.

The images of monarchs on seals are often considered stereotyped and unrealistic, raising the question of whether it is valid to apply ideas of selfrepresentation to such images. In moving away from this anachronistic judgement of medieval seal iconography it becomes clear that a lack of realism does not condemn monarchical seals as empty of self-representative qualities. Indeed, as Brigitte Bedos-Rezak has rightly stressed,

realism is, after all, simply a convention, and one that the Middle Ages did not equate or associate with physiognomic likeness. In the charters themselves, authors refer to their seals as their own image, imago noster, which reveals that seals and their depictions incorporated elements meaningful to self-representation.

Like the documents they authenticated, seals were carriers of meaning and an important channel of communication between a ruler and his subjects.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Inauguration and Liturgical Kingship in the Long Twelfth CenturyMale and Female Accession Rituals in England, France and the Empire, pp. 191 - 214Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2019