The so-called “Prakhon Chai Hoard”Footnote 1 is one of Southeast Asia’s most infamous cases of looting.Footnote 2 It primarily took place over a two-year period from 1964 to 1965 in the province of Buriram, Northeast Thailand. It is generally agreed that it consisted of a cache of bronze sculptures of various sizes, ranging from anywhere between 12 cm to 142 cm in height. The exact number of bronzes looted is difficult to establish. Estimates range from the mid-twenties to as many as three hundred. As discussed below, there have been several attempts to reconstruct the hoard based on extant examples in museums and private collections. This, at the very least, gives us some indication of the numbers involved. Caution needs to be exercised regarding the actual figure of material looted from the site of Plai Bat II, which may never be satisfactorily determined. In Table 1, we list forty-five bronzes and their current whereabouts that we have identified to date that have been attributed to or have been associated with Prakhon Chai or Plai Bat II Temple, either via academic literature or museum websites. This list does not claim to be exhaustive nor, let us reiterate, does it claim that all of these objects are genuine or definitely from Plai Bat II, only that they have been associated with it and/or Prakhon Chai.

Table 1. Bronzes attributed to or associated with Prakhon Chai or Plai Bat II Temple on museum websites and academic literature. They are listed in alphabetical order by current location.

* This is the title assigned to the object by the individual museum or publication.

The vast majority of the bronzes are Buddhist in nature, date to the seventh to ninth century CE, and consist primarily of two- and four-armed bodhisattva figuresFootnote 3 and, to a lesser extent, Buddha images. After their discovery, they were quickly dispersed to museums and private collections overseas, many passing through the London auction house, Spink & Son. It should be noted that, in this instance, Spink & Son functioned more as a clearing house, with none of the sculptures being openly auctioned by them.

For many decades, the exact findspot of the hoard remained vague and obscure. As discussed below, this was most likely unintentional on the part of scholars such as Jean Boisselier and Albert Le Bonheur. Conversely, it seems that individuals such as Douglas Latchford may have purposely employed misdirection out of a desire to conceal it. Much of the initial literature pointed towards a derelict temple on or near the Cambodian border, somewhere in the district of Prakhon Chai. However, no exact findspot was ever given.Footnote 4 As we shall demonstrate, the actual temple – known as Plai Bat II – is in the neighboring district of Lahan Sai. The identity of some of the individuals who orchestrated the looting and facilitated the smuggling and sale of these artifacts abroad also remained shrouded in mystery for many decades.

In this article, we will argue that the late Douglas Latchford appears to have played a central role in the looting and concealing of the location of the hoard and, as stated above, may have purposely employed misdirection to prevent its discovery. We make this assertion based on two sets of evidence. Firstly, our decade-long engagement in the documentation of oral histories of the local community of Ban Yai Yaem Watthana village located near Plai Bat II temple has revealed a clear picture of Latchford’s involvement in the looting. Secondly, the ongoing investigations into Latchford at the time of his death in 2020 have revealed the extent of his looting and smuggling networks. These include investigations by US law enforcement agencies and investigative journalists, the subsequent release of court documents, and access being granted to Latchford’s laptop and archives by his daughter Julia to US law enforcement agencies and the Cambodian government.Footnote 5

This article will attempt to untangle the many myths surrounding the so-called “Prakhon Chai hoard” and paint a much more accurate picture of what occurred. We will henceforth refer to this material as only “the hoard” so as not to perpetuate the problematic association with the Prakhon Chai toponym. We first discuss the hoard itself and the figure of Douglas Latchford to provide some overall context. We then review the associated literature. Doing so, armed with our oral history documentation and the revelations that have come to the fore regarding Latchford, allows us to understand these publications in a new light. We will trace the evolution of the “Prakhon Chai myth” and how this facilitated not only a market for these objects overseas but also obscured their original findspot for many decades. We will then provide a summary of our documentation of villager testimonies to date, indicating how this, combined with our review of the literature, allows us to arrive at a number of clear conclusions surrounding the hoard. These include an estimate of the number of objects looted, the duration of the looting, those involved in it, the ramifications for the local communities involved, and the key role Latchford played in this regard.

Northeast Thailand and the Prakhon Chai Myth

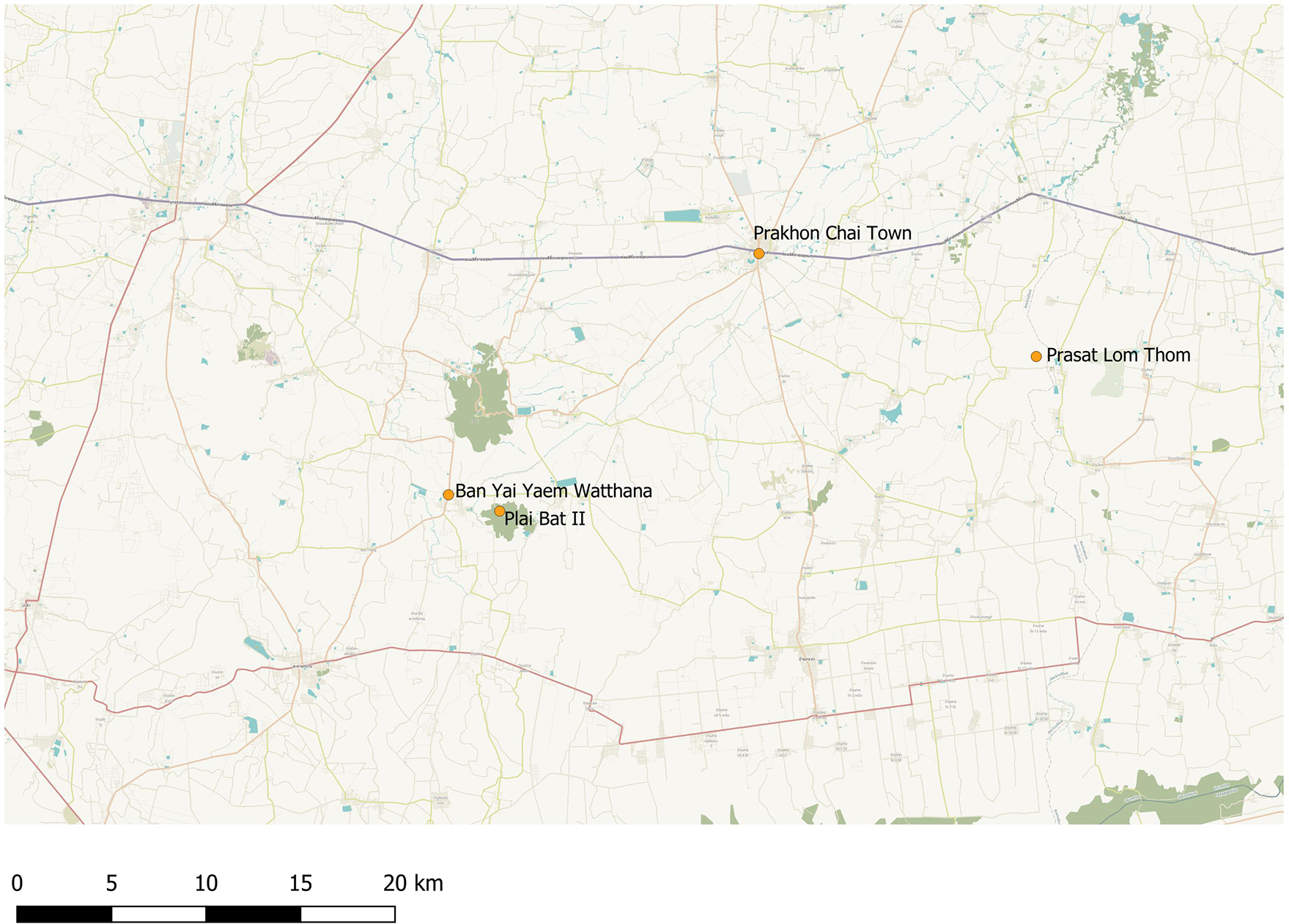

The districts of Prakhon Chai and Lahan Sai are both in Buriram province – one of twenty provinces that make up the region of Northeast Thailand (Map 1). Also known as Isan, it shares its border with Cambodia to the south, Central Thailand to the west, and Laos to its north and east. The region is culturally diverse with much of its population being ethnically Lao. However, the southern provinces of Buriram, Surin, and Si Sa Ket, which share a border with Cambodia, have considerable Khmer and Kuy-speaking populations.Footnote 6

Map 1. Map of Northeast Thailand indicating the main locations discussed in the article. © Stephen A. Murphy.

From the late sixth to early seventh century, Buddhism and Hinduism began to enter the region from both the Dvaravati culture of Central Thailand and the Khmer culture of Zhenla in Cambodia to the south.Footnote 7 A distinctive sculptural style, primarily in stone and bronze, developed in this period with Buddhist, and to a lesser extent, Hindu imagery being fashioned in both the round and in relief.Footnote 8 The bronzes from the hoard, discussed below, are an integral part of this cultural milieu.

Northeast Thailand also contains a wide range of Khmer architectural remains, built in either laterite, brick, sandstone, or some combination thereof. The earliest temples, such as Prasat Phumphon in Surin province, were built in the seventh century.Footnote 9 With the founding of the Khmer Empire at Angkor in 802 CE,Footnote 10 it soon began to extend into the southern regions of Northeast Thailand. By the late ninth to early tenth century, during the reign of the Khmer king, Rajendravarman II (r. 944–968 CE), Northeast Thailand had come under more direct control from Angkor. By the eleventh century, Central and Eastern Thailand had also fallen under the sway of the Khmer Empire.Footnote 11 The temple of Plai Bat II was built in the tenth century during this wave of Khmer political and cultural expansion.Footnote 12

Turning to the hoard itself, there are at least forty-five examples of these bronzes in museums and private collections today that have been attributed to it (Table 1). Most are two- or four-armed bodhisattva figures identified as either Avalokitesvara or Maitreya dressed in an ascetic fashion; that is, devoid of ornamentation or clothing apart from a lower garment. There are also several Buddha images (Table 1, nos. 3, 18, 20, 21, 34) and two small ascetic figures in meditation (Table 1, nos. 8 and 17). Three of the finest examples are today in the Asia Society, New York, the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth Texas, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York respectively (Figs. 1 and 2; see also Table 1, nos. 2, 26, and 35). Bronzes in the hoard have been stylistically dated to the seventh to ninth centuries and exhibit a blend of Dvaravati and Khmer stylistic characteristics.

Figure 1. A “Prakhon Chai Bronze” Bodhisattava Avalokiteshvara currently part of the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. 8th century. Bronze, Acc. no: 67.234.

Figure 2. A “Prakhon Chai Bronze” Buddha image currently part of the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. 8th century. Bronze, Acc. no 982.220.5.

Where these bronzes were made is one of the most debated questions. They reflect highly skilled craftsmanship in the lost wax casting technique and are stylistically sophisticated. To date, no evidence of a bronze forge or workshop has been found in the area surrounding Plai Bat II, nor anywhere in Northeast Thailand for that matter. The bronzes may have been gathered up from throughout the region and could have been produced at a major settlement such as Muang Sema in Nakhon Ratchasima province or Ban Muang Fai in Buriram province.Footnote 13

Another unsolved part of the puzzle is why the sculptures were hidden at Plai Bat II in the first place. The temple is from the tenth century; thus, their concealment must have taken place sometime after this. This would mean that many of the bronzes were already in use for at least two to three hundred years. The most plausible explanation relates to the growing Khmer presence in the region. The Khmer elite was primarily Saivite – a sect dedicated to the worship of the god Siva – and this form of Hinduism would have eclipsed Buddhism to a certain extent during the tenth and eleventh centuries. However, as the temple site of Phimai illustrates, Buddhism still played a prevalent role.Footnote 14 As the Khmer tightened their grip on the northeast, these bronzes may have fallen out of ritual use as Buddhism waned and had subsequently been collected up and ritually interred. This would at least explain their location in a Khmer temple. Furthermore, the first object discovered by villagers at Plai Bat II was a Buddha under the Naga sculpture.Footnote 15 Dating to the eleventh century, this sculpture would have functioned as one of its cult images and suggests that Plai Bat II had Buddhist elements to it.Footnote 16 The tragedy here is that, because the site was looted as opposed to archaeologically excavated, we will most likely never know the answers to these questions as any potential evidence that could shed light on this question has now been irrevocably lost.

Douglas Latchford

Douglas Latchford was born in Mumbai on 15 October 1931. Educated in England, he made his way to Thailand in the 1950s where he worked in the pharmaceutical industry, setting up his own company and investing in real estate.Footnote 17 There he began to develop an interest in Southeast Asian art, and that of Khmer culture in particular. For many decades after that, he was known in art history and museum circles as a passionate and dedicated collector of Khmer sculpture. But beneath this carefully cultivated façade of an upper-class British expat art lover lay a murkier reality. By the time of his death in 2020, the extent of his involvement in the illicit looting, smuggling, and selling of South and Southeast Asian antiquities had been laid bare for all to see. Latchford’s fall from grace has been well-documented.Footnote 18 Herein, we provide a short summary of it and highlight some of the salient points regarding the hoard.

The veil began to drop in around 2012 when US law enforcement – specifically the Department of Justice U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York – opened both civil and criminal cases against Latchford, accusing him of being involved in the looting and trafficking of Cambodian antiquities. This was sparked by the attempted sale of a Khmer sculpture from the site of Koh Ker at Sotheby’s New York.Footnote 19 In December 2016, a well-known New York dealer, Nancy Weiner, was arrested as part of “Operation Hidden Idol,” a federal investigation into another disgraced art dealer, Subash Kapoor.Footnote 20 In a subsequent plea deal, she explained how she helped Latchford falsify documents for a number of illegally imported sculptures. She also names Emma Bunker as the academic who often worked with Latchford and also implicated her in the forging of provenances.Footnote 21 In 2019, a federal grand jury charged Latchford with a litany of crimes including smuggling and wire fraud, but he died in 2020 before he could stand trial. In June 2023, his daughter agreed to a $12 million settlement, which also included the forfeiture of a seventh-century bronze from Vietnam.Footnote 22

While the indictments, court testimony, and plea deals do not specifically refer to the hoard or its bronzes – they discuss primarily Cambodian material – they clearly show Latchford’s modus operandi. On numerous occasions we see him forging provenance documents for sculptures, often in cahoots with Emma Bunker and Nancy Weiner. The naming of Bunker as a willing accomplice is particularly significant given that she wrote two of the most important articles on the hoard (discussed below).

The court documents show that Latchford was part of a well-organized smuggling network that operated within both Thailand and Cambodia. Simon Mackenzie and Tess Davis have attempted to reconstruct these networks and identify an individual whom they refer to as a Janus figure.Footnote 23 This is someone who faces both ways. One face looks towards the illicit side of the enterprise – that is the looting and smuggling—while the other looks towards the (supposedly) reputable side – that is the dealers, auction houses, and museums. Mackenzie and Davis do not specifically identify who this Janus figure is, but in a later interview, Davis confirms that it was Latchford.Footnote 24

From the revelations that have come to light since 2012 and our interviews with villagers since 2014, it is now abundantly clear that Latchford was intimately involved in the looting, trafficking, and illegal sale of numerous bronzes from the hoard. It also appears that he used Bunker to help publicize and legitimize the material insofar as her scholarship started to build an art history around these objects – an essential aspect of connoisseurship and the creation of a market from them in museum and art world circles. It also appears that he may have purposely obscured the findspot, but this is difficult to prove. This misdirection, intentional or otherwise has, until recently, sent many a scholar on a wild goose chase around the Prakhon Chai district.

Making sense of the literature

What follows is a chronological review of the literature on the hoard (Table 2). In doing so, we trace the evolution of this discourse and identify how certain misrepresentations developed over time. Armed with the knowledge obtained from our interviews with villagers and the revelations about Latchford discussed above, we can now begin to untangle these deceptions and expose the rationale behind them.

Table 2. Chronological sequence of the literature on Prakhon Chai.

The first mention of the hoard occurred in the Illustrated London News, published on August 28, 1965, under the heading “Unique Early Cambodian Sculptures Discovered.”Footnote 25 The anonymous article describes how a number of bronze sculptures were found near the Thai-Cambodian border. Significantly, it does not reveal the exact location, and the article appears intentionally vague. It does, however, mention that the discovery took place in a derelict temple by two “Cambodian villagers.”Footnote 26 The identification of this temple would become the source of much conjecture and speculation over the following four to five decades.

The images in the Illustrated London News article are credited to Andrew Maynard of Spink & Son. We know that he was the main conduit through which much of this material was sold to either private collectors or museums in the West, and the article states that the three objects illustrated were already in the auction house’s London galleries. However, it is not clear how he obtained the objects or the information regarding their findspot. Furthermore, while the Illustrated London News article is anonymous, it is clear that whoever supplied the information to both Maynard and the Illustrated London News had first-hand knowledge of the discovery. Who this person was remained a mystery for many years. Based on our interviews of local villagers, discussed below, and information from Latchford’s personal archive and emails, we strongly suspect that it was him but we unfortunately do not have definitive proof in this regard.

Another puzzling detail is the statement that “an archaeologist was called in to secure the recovery of the statues.”Footnote 27 No individual has ever come forward in this regard nor is there any record in the Fine Arts Department of Thailand (FAD)Footnote 28 documentation of them sending an archaeologist to recover these objects. In fact, as we will see, the FAD was for many years unsure of the exact location of the temple and even misidentified it at one point.

Furthermore, if a government archaeologist had been sent to recover the sculptures, they would have then been brought to the National Museum Bangkok and become property of the state. It is possible that the mention of an archaeologist was a spurious detail concocted to add an air of legitimacy to the hoard and its subsequent sale overseas.

Shortly afterward, in 1967, Jean Boisselier, a respected French art historian and the leading authority on Thai and Cambodian art of his day, published the first academic piece on the bronzes.Footnote 29 He attempted to place the hoard within a wider cultural, artistic, and chronological context of Northeast Thailand and Cambodia. In this article, we hear for the first time that the hoard was found in the Prakhon Chai district, Buriram province in 1964, a year before the Illustrated London News article appeared.Footnote 30 Furthermore, Boisselier goes on to state that at least one hundred bronzes were discovered.Footnote 31 However, he provides no information as to how he established the location of the findspot nor the number of objects recovered. Furthermore, Prakhon Chai, as mentioned above, is a district in Buriram province, not an archaeological site or temple. Whatever the actual truth of the matter, this designation obscured the true origin of the bronzes and attached to them a name that would stick to the present day – the Prakhon Chai hoard. This would be further solidified four years later by Emma Bunker, discussed below.Footnote 32

Based on stylistic analysis, Boisselier proposed a date range of the seventh to ninth centuries for the now newly named “Prakhon Chai bronzes/Prakhon Chai hoard.”Footnote 33 Boisselier’s article thus established three pieces of information about the bronzes that henceforth became taken as fact. Firstly, that they came from Prakhon Chai; secondly that at least one hundred objects were uncovered; and thirdly that they date from the seventh to ninth centuries and reflected an artistic style unique to Northeast Thailand. As we will show, the first statement, that they came from Prakhon Chai, is erroneous. The second statement, that there were at least one hundred of them, is impossible to confirm with any certainty (see Table 1). The third statement, that they date from the seventh to ninth centuries, is generally accepted to be correct.Footnote 34

Meanwhile, in Thai art history circles, word was also getting out about the hoard. From 1968 to 1973, three exhibitions took place at the National Museum Bangkok in which three of the bronzes from the hoard from private collections in Thailand went on display alongside other objects. The first ran from 6 March to 6 April 1968. In it, two bronzes were displayed as part of a larger exhibition on antiquities in private collections in Thailand.Footnote 35 Both were owned by Prince Bhanubhan Yugala. No explanation is given as to how the prince obtained them, but as the author and leading Thai art historian of the day M.C Subhadradis Diskul lamented, there were now very few bronzes from the hoard remaining in Thailand.

It is a great pity that many of the images that belong to this large group of bronzes discovered at Prakhon Chai, Buriram, were most likely smuggled out of the country. Only a few of them have gone into private collections in Thailand, and none have been obtained by the Thai National Museums.Footnote 36

This was followed in 1970 by an exhibition titled The Cultural Heritage of Thailand before the thirteenth century, which ran from 3 November to 30 December of that year, once again at the National Museum Bangkok.Footnote 37 This time a small bronze belonging to the Department of Archaeology, Silpakorn University was exhibited.Footnote 38 No details were given in the accompanying publication as to how this latter bronze reached the Department of Archaeology, nor where it was from. However, in a 1973 article, Diskul reveals that it had been donated by none other than Douglas Latchford and was now part of the University’s museum collection.Footnote 39 This was the first time Latchford’s name surfaced in relation to the hoard, although it was misspelled as “Lashford.”Footnote 40 Like his French contemporaries, Boisselier and Le Bonheur, there is no indication here that Diskul was aware of Latchford’s role in the looting and smuggling. Latchford’s name then quickly recedes into the shadows as swiftly as it had appeared. Diskul ends his article with a strongly worded admonishment of Thai officials (presumably aimed at the FAD), criticizing them regarding the hoard. He states, “I hope that this matter will be one of concern to the officials responsible within Thailand so that this cannot happen again.”Footnote 41

Meanwhile, in 1972 a short article appeared in the Archives of Asian Art by Emma C. Bunker, who at the time was a little-known scholar in the field of Asian art.Footnote 42 In it, she too reiterates that the hoard was discovered in 1964 at Prakhon Chai.Footnote 43 However, she does not indicate how she has established these “facts” and instead references Boisselier’s Reference Boisselier1967 paper and the Illustrated London News, thus perpetuating the unsubstantiated claim made by her more illustrious French predecessor.

Bunker’s article is significant as it was the first time three photographs of the “derelict temple,” mentioned in the Illustrated London News, were reproduced.Footnote 44 The caption for Figure 1 in her article reads “temple precinct at Pra Khon Chai” while her Figure 2 claims to show the open burial pit where the bronzes were reportedly found. Furthermore, she provides twenty-four photographs of bronzes in private collections and museums overseas said to be part of the hoard.Footnote 45 This is significantly more than Boisselier, who only published four.Footnote 46 This was the first time many of these bronzes had been published. Bunker uses these twenty-four images to refine and develop Boisselier’s chronology further.

However, Bunker makes no mention of how she obtained the photographs of the temple. She does though explain how she compiled the twenty-four images stating that due to “… the kindness of numerous dealers, collectors, and scholars,3 the large pieces can now be accounted for, although the [whereabouts] of many of the smaller pieces still remains unknown.”Footnote 47 In footnote 3 in the above quote, she names four of these individuals – Robert Ellsworth, Ben Heller, both of whom were prominent US-based collectors listed in her article as owning Prakhon Chai bronzes, Adrian Maynard (from Spink & Son), and Mary Lanius. Douglas Latchford’s name is conspicuously absent. Furthermore, in her 2002 article (discussed below), Bunker publishes the same three images of the temple, revealing in footnote 4 that the images in her 1971/1972 article were from “a knowledgeable friend.”Footnote 48 This, we argue, is most likely Latchford as our documentary evidence from local villagers (below) shows that he was active at Plai Bat II during the looting in 1964.

However, what is not clear at this point is whether Bunker knew that the temple in the photographs was not located in the Prakhon Chai district. Either way, in 2002, she revealed for the first time in her Arts of Asia article that the temple is known as Plai Bat II in Lahan Sai district, Buriram province.Footnote 49

Adding to the confusion, in 1972, Albert Le Bonheur, a curator at the Musée national des Arts Asiatiques Guimet (Guimet Museum) Paris, who had recently acquired one of the bronzes for his institution, wrote an article on the topic.Footnote 50 In it, he states that in his correspondence with Boisselier, the latter had proposed that the findspot was possibly Prasat Lom Thom temple in Buriram province.Footnote 51 This Khmer temple was first surveyed and published by Etienne Lunet de Lajonquière in Reference Lunet de Lajonquière1907, listed as temple number 399.Footnote 52 However, once again, no reason is given for this identification. We can assume that Boisselier made this tentative identification given that this temple is only about 15 km to the southeast of Prakhon Chai town and, as will be discussed below, Plai Bat II did not appear on any of the FAD archaeological surveys until 1993,Footnote 53 nor was it listed in Lunet de Lajonquière’s work. Plai Bat II temple was thus largely unknown to scholars and Thai officials at this time.

To confuse matters even more, Le Bonheur states that nearly three hundred bronzes were recovered. Where he got these figures from is also unclear.Footnote 54 Woodward rightly cautions that this is most likely an exaggeration and suggests that this figure could have come from Andrew Maynard.Footnote 55 The oft-cited claim that there are three hundred bronzes seems to have originated here.

From October 16 to November 30, 1973, another significant exhibition took place at the National Museum Bangkok. It was occasioned by the discovery of three bronzes that had recently been unearthed by a landowner in the village of Ban Fai, Buriram province. The landowner had informed the authorities of their discovery, and they were subsequently acquired by the National Museum Bangkok for 100,00 Baht.Footnote 56 A publication written by a number of Thai museum and FAD staff accompanied the exhibition but, at this stage, things became even more muddled.Footnote 57 Firstly, the authors repeated the claim that about three hundred bronzes were looted from Prakhon Chai and cited Bunker’s 1971/72 article as the source of this information.Footnote 58 Bunker, however, never once mentioned this figure. Furthermore, in their discussion of the three newly acquired bronzes, they compared them to the bronzes from the hoard.Footnote 59 To do so, they reproduced the twenty-four images in Bunker’s article.Footnote 60 They also stated that the findspot was Prasat Lom Thom temple and cited the footnote in Le Bonheur as their source.Footnote 61 They then somewhat surprisingly make the baseless claim that Bunker copied Figure 1 in her 1971/Reference Bunker1972 article from Lunet de Lajonquière’s published work. They even reproduced her image with the following caption; “Temple at Pra Khon Chai, copied from Lunet de Lajonquière, -- Inventaire descriptif des monuments du Cambridge, t II, Reference Lunet de Lajonquière1907.”Footnote 62

This assumption on the part of the FAD is perhaps understandable insofar as Bunker never revealed the source of her images. However, it appears that the FAD never verified that the said image was from Lunet de Lajonquière. Even a cursory check of Lunet de Lajonquière’s work would show that the photograph was not from his publication. This is quite a remarkable oversight. Furthermore, if they had visited the site of Prasat La Lom Thom they would have quickly realized that Figure 1 in Bunker did not match either the description or site plan given by Lunet de Lajonquière.Footnote 63 In the end, they did neither. This mistake further added to the confusion over the actual findspot of the hoard.

However, only a year later, Hiram Woodward, in his review of the FAD’s exhibition booklet, had already called this identification into question. He points out that the claim made by the FAD that Bunker copied her image from Lajonquière was false, arguing that:

It is impossible to determine with certainty whether the photographs published by Mrs. Bunker are in fact views of Prasat Lom Thom; Lajonquière mentions sandstone false doors, for instance, while Mrs. Bunker’s photographs show only ones of brick. The treatment of the issue of the exact provenience of the “Prakhonchai” bronzes, ten years after their discovery, is the most dismaying aspect of the Fine Arts Department’s book.Footnote 64

In 1993, the FAD finally surveyed Plai Bat II but, even then, misidentified it as Plai Bat I in the publication.Footnote 65 Furthermore, the publication failed to make the connection between this temple and the hoard. As will be shown below, if they had taken the time and effort to consult the villagers, they may have been able to do so.

In 1994, the first high-profile international exhibition of bronzes from the hoard took place at the Asia Society New York. Called Buddha of the Future: An Early Maitreya from Thailand, it ran from April 13, 1994 to July 31, 1994, and was centered around a bronze in their collection, arguably one of the finest from the entire hoard (Table 1, no. 2).Footnote 66 This was supplemented by loans from the National Museum Bangkok of the Ban Tanot and Ban Fai bronzes as well as objects from numerous private collections in the United States. It is curious that the FAD acceded to loaning objects to this exhibition given the dubious means by which many of the objects on display from private collectors were acquired and the criticism leveled at them by Diskul some twenty years earlier. Furthermore, Latchford’s name surfaces once again, if only momentarily. It does so in connection with a sandstone Buddha image that he lent to the show, but no other mention of him or information is given.Footnote 67

The exhibition catalog consisted of two essays by Nandana Chutiwongs, a Thai art historian, and Denise Patry Leidy, the then-curator of the Asia Society. However, neither author provided any new information regarding the origins of the hoard. In fact, the exhibition functioned instead to reaffirm the baseless provenance of Prakhon Chai by citing the existing literature on the topic.Footnote 68

Eight years later, for the first time, we finally hear the true location of the hoard. In 2002 Bunker published a paper in the trade magazine Arts of Asia titled “The Prakhon Chai Story: Facts and Fiction”Footnote 69 wherein she reveals that the temple in the photographs from her 1971/1972 article is in fact Plai Bat II. She also notes that it had been misidentified by both Boisselier and the FAD as Prasat Lom Thom.Footnote 70 Several questions immediately spring to mind here. Firstly, how did Bunker finally figure out that the temple was Plai Bat II? In her paper, she mentions that she did so through discussions with villagers, but again fails to disclose how she knew which village to visit in the first place.Footnote 71 Secondly, if she knew for many years that Prasat Lom Thom was not the correct temple, why did she wait so long before revealing this? Thirdly, she once again fails to disclose where she obtained the original photographs, stating only that they were from a “knowledgeable friend.”Footnote 72 We argue that they were most likely supplied by Douglas Latchford. It is clear from email correspondences between them, which are now publicly available, that he knew for decades that Prakhon Chai was the incorrect findspot.Footnote 73

Bunker’s Reference Bunker2002 article was also significant in another way. In the appendix, she attempts to reconstruct the original hoard by compiling many of the known examples in museums and private collections worldwide, some published for the first time. Doing so, she brings the total number to thirty-six. This is well short of the supposed three hundred. Her reconstruction is the first clear attempt to understand the actual size and character of the hoard.

Bunker also reveals that the first object discovered by villagers at Plai Bat II was a sandstone image of the Buddha under a naga. However, attempts to illegally remove it from the site were intercepted by local police, the sculpture was confiscated, and is today part of the collection of the National Museum Bangkok.Footnote 74 This raises unanswered questions as to why local police intervened in this specific case but not subsequently. We did, however, manage to interview two villagers in this regard (see below).

In 2011 Bunker and Latchford self-published Khmer Bronzes: New Interpretations of the Past. Footnote 75 This lavishly illustrated tome contained many previously unpublished images of numerous objects in private collections. Many belonged to Latchford himself and, along with its companion volume Adoration and Glory: The Golden Age of Khmer Art,Footnote 76 revealed publicly for the first time the extent of his collections.Footnote 77 These vanity publications aimed to legitimize Latchford’s credentials, facilitate sales of his collections to museums and collectors, and further cement Bunker as a leading figure in Southeast Asian art history. This all came to an abrupt end when US law enforcement agencies commenced investigations against him. In an ironic twist of fate, both volumes have now become indispensable tools in the fight to recover the stolen heritage of Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam.

The 2011 publication has a short section on the material from the hoard, and the authors once again state that the correct location is Plai Bat II temple, not Prakhon Chai. They illustrate nine of the bronzes, one of which was in Latchford’s collection.Footnote 78 Another bronze, now at the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco and part of the Avery Brundage Collection (Table 1, no. 7), which does not appear in Bunker’s previous articles, is said to be from Plai Bat II, despite belonging stylistically to Srivijayan art associated with Southern Thailand and Sumatra, Indonesia.Footnote 79 It would thus be impossible on stylistic analysis alone to attribute this bronze to Plai Bat II. One wonders therefore on what grounds they make this claim.

The discussion overall is ostensibly about the place of these objects within the larger tradition of Khmer bronzes in general. However, towards its end, it highlights the fact that there are now numerous forgeries on the market and cites one specific example.Footnote 80 The issue of forgeries deserves a much fuller discussion than that which can be provided herein. However, what we can say at this point is that looting facilitates forgeries as, 1) it creates a market for certain objects; 2) as they were not recovered archaeologically, there is no precise record of how many were found; and 3) the oft-cited number of three hundred bronzes may have been planted by dealers such as Andrew Maynard and individuals such as Latchford to enable such practices.Footnote 81

Despite Bunker’s revelations in her 2002 and 2011 publications, they initially appeared to have little impact on scholarship and went largely unnoticed. It was not until 2014, with the publication of Lost Kingdoms: Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Early Southeast Asia, the museum catalog for a major exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York of the same name on Southeast Asian sculpture, that people started to take note.Footnote 82 The exhibition borrowed two bronzes from the hoard to display alongside the one in its collection and for the first time gave the findspot and provenance of these objects in their museum labels as Plai Bat II. The high-profile nature of the exhibition brought this new information to a much wider audience, a fact that Latchford and Bunker were clearly uneasy with.Footnote 83

Guy’s Reference Guy2014 publication was the last to discuss the bronzes from a purely art-historical standpoint and brings our literature review to a close. Subsequent publications have begun the task of telling the story behind the looting and the role of those who have worked on exposing this.Footnote 84 Our article continues in the same vein and, with this in mind, we now turn to a review of our documentation of villager testimonies at Plai Bat II.

Oral Histories of Looting: The Villagers of Ban Yai Yaem Watthana

We hope that it is now apparent that it would be extremely difficult to piece together the actual events that took place in 1964 and the subsequent looting and illicit trafficking based on the extant literature alone. Thus, on March 7, 2014, armed with Bunker’s Reference Bunker2002 article, we set out to visit Plai Bat II ourselves and speak to the villagers (Map 2, Fig. 3). It quickly became apparent that there was still a strong collective memory among the community in Ban Yai Yaem Watthana, the nearest village associated with Plai Bat II temple, regarding the looting that took place there some five decades earlier. There was also a willingness to share information with us.

Map 2. Map indicating the location of Plai Bat II and Ban Yai Yaem Watthana in relation to Prakhon Chai and Prasat Lom Thom. © Stephen A. Murphy.

Figure 3. Plai Bat II temple in January 2024, courtesy of Stephen A. Murphy.

After the initial visit that day by the three of us, two of this article’s authors (Tanongsak Hanwong and Lalita Hanwong) returned frequently over the course of the next ten years to document and record these oral histories of looting.Footnote 85 This has allowed us to piece together the events that took place and the villagers’ role in it. We have also been greatly aided in this task by the concurrent investigations that took place into Latchford and Bunker over the past decade, as discussed above. What follows is a summary of the key observations and conclusions that we have drawn from our interviews.

Two of the first villagers that we met were Yod Phonsomwang, who was 94 years old at the time, and Chuai Mulaka, who was 80. In our initial discussions with Chuai Mulaka, he immediately recognized many of the images we showed him in Bunker’s Reference Bunker2002 article and confirmed that these were all looted from Plai Bat II temple.Footnote 86 Aware that Bunker had said in her article that she had spoken with villagers, we wanted to verify this. To do so, we showed Chuai a picture of both Douglas Latchford and Emma Bunker. He was immediately able to identify them both by name. Chuai sadly passed away on July 8, 2018 at the age of 84.

We were also able to establish from our interviews that Latchford was often present during the looting that took place between 1964 and 1965. He also had a Thai middleman named Boonlert who worked for Osotspa Public Company Limited, a pharmaceutical company. This appears to have been his initial connection to Latchford, who also worked in this industry. Boonlert and Latchford set up an office in a house in the village, and Boonlert sometimes functioned as Latchford’s driver. The house belonged to Singto Rojanabundit. This information was supplied to us by Singto’s son, Satien Rojanabundit, as his father had long since passed away.Footnote 87 Satien, who was a boy at the time, clearly remembers Latchford’s frequent visits. He recounted how Boonlert would often come with Latchford to buy pieces from the village. At times, he would also act as an agent for Latchford and base himself at Satien’s house. Here, with the help of Chuai Mulaka, they would gather up the bronzes.

Thanks to documents shared with us by Bradley Gordon from Douglas Latchford’s archive, we also have independent corroborating evidence indicating that Boonlert and Latchford worked together. In a series of correspondences from August and October 1975 between Latchford and Samuel Eilenberg, a Columbia University professor and prominent collector of Asian art, the pair discuss a bronze that Eilenberg had acquired, which had previously belonged to Latchford. Given its height, it is most likely Fig. 11 in Bunker’s 1971/1972 article (Table 1, no. 15), which credits Eilenberg as its owner. Latchford, in a letter dated September 22, 1975, states:

In October 1965, when I passed through New York with Mr. Boon-Lert, we had dinner at your apartment one evening and you showed us a Pra Kon Chai Bronze about 13” high which I remarked had originally belonged to me. I asked who you had bought it from and I think you said Peng Seng and the price, I believe was either $10,000 or $12,000.Footnote 88

We can see from this correspondence and the villagers’ testimony that Latchford and Boonlert were actively involved in the looting and trafficking of the bronzes from Plai Bat II right from the beginning of 1964/1965. Peng Seng was a well-known Thai antiquities dealer in Bangkok who also worked closely with Latchford.

Our interviews also revealed that almost everybody in the village knew about the looting. It continued for about two years, spanning 1964 and 1965. At that time, most men of working age in the village were involved because they needed the money. Latchford paid them well compared to what they could earn from farming. Some of the villagers, such as Satien’s father, Singto, earned enough to buy a jeep, something almost unheard of at the time.

Another villager, Son Chantasi, the former village headman, was a young boy at the time and remembers bringing food to his father at Plai Bat II each day. Villagers would reserve their own plots and would only pause when police officers came.Footnote 89 Villagers also told us that over the course of the two years, many of them stayed on the grounds of Plai Bat II temple. The women would cook and the men would dig often throughout the night. There are also accounts of them washing and cleaning the bronzes once they were found. Many villagers can still recall the exact objects recovered. Samak Promrak, for instance, was in his mid-20s at the time. He claims to remember the day the large Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, which is today in the Metropolitan Museum of Art New York (Table 1, no. 35), was uncovered.Footnote 90

From the accounts of the villagers, it appears that after about two years, the site of Plai Bat II had been completely pillaged. It is hard to estimate exactly how many bronzes were found but, according to Chuai Mulaka, it could be as many as three hundred.Footnote 91

We also learned that it was Mr Pong Yangmee and Mr Ken Bungthong, two villagers from Ban Yai Yaem Wattthana, who found the large Buddha under the Naga mentioned by Bunker in her 2002 article.Footnote 92 They recounted how the district officer of Lahan Sai, Mr Sompon Pongsawad, confiscated it and handed it over to the 6th Regional Office of the Fine Arts Department in Phimai on February 11, 1966. According to the villagers we interviewed, Mr Sompon Pongsawad was shot dead on January 15, 1967, at 8.30 pm at Ban Suksamran, Tambon Pakham, Lahan Sai District because he also confiscated bronzes from the villagers but did not pass them on to a museum or the Fine Arts Regional Office. It is believed that he was assassinated because some villagers were furious that they did not get any money from him, but we have been unable to confirm this.

While this is the only account of looting-related violence we have encountered during the course of our interviews, its specter is always there to a certain extent. We are reminded of accounts provided by Mackenzie and Davis in their research into looting in Cambodia and the criminal gangs who operated along the Thai-Cambodian border. As they have documented, the threat of violence was commonplace, as can be seen in the murder of a Cambodian smuggler’s uncle in Sisophon.Footnote 93 However, in Ban Yai Yaem Watthana, this level of criminality never took hold. It seems that, by and large, the villagers, by dividing up the site into plots, mitigated against such circumstances.

In conclusion, villagers also told us that even after the looting ended, Latchford remained a frequent visitor to the site. They recounted how for many years he would return to the village, go up to Plai Bat II, look up at the sky, look at the temple, and feel grateful because of how much he had profited from it. Each time he would go back he would give money to people and children from the village. This should come as no surprise. As Bradley Gordon, puts it, it appears that the hoard “… might have been Latchford’s first big heist.”Footnote 94

This is significant as it provided him with the financial clout, local networks, and overall nous to expand his operations into both Northeast Thailand and, increasingly, Cambodia. As Bradley Gordon and his team have clearly documented, Latchford was a major player in the looting and smuggling of Cambodian antiquities for many decades until the time of his death. The hoard from Plai Bat II thus acted as the genesis of his looting and smuggling networks that would wreak so much havoc and destruction of Cambodian and Thai cultural heritage over the next five decades.

Conclusion

Today, we have a much better understanding of the events surrounding the looting of the hoard. However, much is still unclear and may, unfortunately, forever remain so. Such is the lasting legacy of looting. Based on our documentation of villager testimonies, we now know for certain when and where the looting took place, who was involved, and the impact it had on that community. At the same time as we were conducting our interviews, Latchford’s world began to unravel, and by 2019 a criminal case was brought against him. His subsequent downfall, albeit posthumously, has allowed us access to his archives and court testimony. Reviewing the literature in light of this, we have been able to unravel much of the misdirection and misunderstandings that took place. In doing so, we hope that we have finally brought some much-needed clarity to one of the most notorious cases of looting in Southeast Asia.

What then should happen next? The Thai government, through its Committee on Repatriation of Stolen Artifacts, is in the process of making claims regarding some of this material, but it is a difficult task given its widespread dispersal and the uncertainty surrounding which objects came from the original hoard (see Table 1). However, at the time of writing, we know that the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco is in the process of deaccessioning most of its Plai Bat II material (Table 1, nos. 3-6) so that it can be repatriated to Thailand. We can only hope that other museums, collectors, and cultural institutions in possession of material from the hoard will follow suit. This would at least provide some means of redress for the wrongs perpetrated by Latchford and his collaborators.

Acknowledgements

We would first and foremost like to thank the villagers of Ban Yai Yaem Wattthana for sharing their memories and providing us with detailed information on the events that occurred. We would also like to thank Bradley Gordon for providing us with documents from the Latchford archive relating to Prakhon Chai material. Thank you too to Matthew Campbell and the two anonymous peer reviewers for their helpful comments on this article.

Funding

Stephen A Murphy would like to acknowledge and thank the following funding bodies: Fieldwork to Thailand in September 2023 was provided by the Southeast Asian Art Academic Fund at SOAS, University of London; Fieldwork to Thailand in January 2024 was carried out in conjunction with the Getty Foundation Connecting Art Histories Grant Circumambulating Objects: on Paradigms of Restitution of Southeast Asian Art.