Introduction

The indigenization of management and organizations in the postcolonial world, examined through various terms like “Africanization” or “Indianization,” was a major political issue in most of the newly independent states.Footnote 1 It was one of the major risks faced by multinational enterprises (MNEs) during the second part of the twentieth century.Footnote 2 In their study of the international human resource management strategy of the Burmah Oil Company in India, Abdelrehim, Ramnath, Smith, and Popp find that the continued deployment of British expatriates and the company’s slow rate of Indianization elicited dissent from the Indian government that culminated in the company’s nationalization in 1976.Footnote 3 In Indonesia, Sluyterman argues that Dutch multinationals deployed European expatriates in the top managerial positions to maintain control and operational efficiency. However, the Indonesian government’s persistent demands for Indonesianisasi forced the multinationals to train locals and later post them in middle managerial positions, while others opted for lucrative government jobs.Footnote 4 Expropriation was an alternative and hostile means of seizing foreign-owned property without legitimate compensation to the owners in former colonies in Asia and Africa. Bucheli and Decker argue that this form of decolonization occurs when there is host political collusion between the government and local business owners, the government and local workers, or between the government and civil servants to support and expedite the process.Footnote 5 In Africa, the focus of this paper, the term “Africanization” in the 1960s and 1970s denoted expropriation of foreign entities or their assets in the continent and was part of the decolonization process that was taking place especially in Nigeria and Ghana.Footnote 6 Decker further argues that British multinationals faced with legitimacy challenges adopted different staffing approaches and Africanized their subsidiaries to survive in Britain’s former colonies in West Africa.Footnote 7

After attaining their independence, most nationalistic African states called for greater involvement of the locals in strategic economic sectors, which were still under European control.Footnote 8 During the decolonization negotiations that transpired between 1945 and 1954 in Egypt, the rise of nationalistic movements demanded Egyptianization of industries, and the United Kingdom (UK) was obliged to safeguard its political and military interests in the country.Footnote 9 Nigerianization of board and managerial positions of Barclays Bank DCO from the pre-independence era, although slow, proved crucial in diffusing tensions between the London headquarters and local politicians who wanted greater control of foreign investments in the country.Footnote 10 Nigeria’s indigenization policy of 1972 was enacted to liberalize the strategic sectors from foreign dominance and boost locals’ active involvement in profitable sectors, hence minimizing profit expropriations.Footnote 11 Kenya established a Kenyanization Personnel Bureau in 1967 to fast-track the localization of industries, because the government deemed the process slow, and subsequently pursued state capitalism through various state agencies as an intermediate stage of establishing African capitalism, although these efforts failed, as discussed by Himbara.Footnote 12

According to the literature, the Africanization of management had ambivalent results. Some scholars emphasized that MNEs were prepared to face this issue and internalized it before independence in the management of their African subsidiaries, although it was not an easy process. In her study of British MNEs in Ghana and Nigeria, Decker argues that localization was initially conducted to mitigate political risks—albeit the process encountered hurdles such as lack of internal development of African employees—but training programs were later instituted to build the locals’ capacities.Footnote 13 Moreover, the appointment of local non-executive directors and managers provided access to key political networks and business intelligence.Footnote 14 Morris’s study of Barclays Bank DCO in Kenya finds that in the imminence of independence, the bank anticipated the institutional changes and extended its business goal beyond the traditional focus on expatriate banking and financing European plantations. It opened branch networks across major towns and offered current accounts, savings accounts, and credit facilities to the locals. Indigenizing some management positions provided access to key local networks, proved less costly in operations compared with an expatriate workforce, and cushioned the bank from vilification by nationalistic politicians.Footnote 15

Conversely, other scholars stress the unproductive effects of Africanization on MNEs that adopted such practices. Himbara argues that attempts by the state to fund the African bourgeoisie in Kenya through state agencies to steer commerce and industry stalled because the state agencies tasked with implementing the policy lacked sufficient funds and technical skills.Footnote 16 Morris finds that the employment of locals in Barclays Bank DCO in Kenya was based on individuals’ disposition rather than qualifications, and managerial appointments were a form of tokenism and reward to political cronies.Footnote 17 In the aviation industry, the replacement of French expatriates with locals has been highlighted as one cause of the multi-flag carrier Air Afrique’s collapse due to poor management and skill deficiency.Footnote 18

Finally, the indigenization of the public sector in post-independence African countries has been almost a given, with control passing from the (foreign) settler to local governments. This process often occurred in tandem with nationalization when public services and strategic resources were controlled by private companies under colonial rule. The natural resource industry is a notable example of local governments taking control of foreign companies, for example, iron in Mauritania; phosphates in Benin; and copper in Sierra Leone, Zambia, and Zaire.Footnote 19

Our focus is on a former colonial firm, East African Airways Corporation (EAAC), and a firm that emerged from its collapse, Kenya Airways (KQ).Footnote 20 The former was managed by the colonial administration and later in the post-independence era by the three East African states: Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania (former Tanganyika and Zanzibar). Throughout this study, the term “East Africa” refers to these countries, unless stated otherwise. The continuity of operations and change of ownership offers an opportunity to carry out a long-term analysis of human resource management in the EAAC and KQ and discuss the subject of Africanization within the context of these firms. One major issue is to understand to what extent the change of ownership was a major break in the recruitment policy of these companies. Hence, our objective is to discuss human resource management before and after the change of ownership from the postwar years. As a case study, we explore the process of recruitment, training, and integration of the local workforce in EAAC in the colonial and postcolonial period, and subsequently in KQ since 1977. The choice of these firms is instructive, because the aviation industry is technology intensive and competitive and requires competent human resources to ensure high safety standards and a competitive edge. KQ was chosen because it is the most successful airline out of the three that emerged from the defunct EAAC and has been operational to date.

The main research questions addressed by this paper are: How did airline companies in East Africa manage human capital since the end of World War II? How did this policy change over time? Secondary questions include: How was human capital development accomplished? To what extent was Africanization a political objective? This study is based on EAAC and KQ documents kept at the Kenya National Archives in Nairobi, consisting of primary sources (minutes of the board, correspondence, and internal memos) and annual reports, which were consulted from February 28 to July 28, 2020, and interviews with eight former African and two Dutch KQ executives between March 1 and April 30, 2020. Secondary sources include business newspaper articles, including the Financial Times.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: The second and third sections provide an overview of the development of aviation in Africa to explore the context in which airline companies evolved, with a focus on EAAC’s human capital development during and after colonization. The fourth section analyzes the case of KQ, and the fifth section discusses the results and presents our conclusion.

Development of Airline Business in Africa

After the end of World War I, European countries such as Britain established state airline monopolies, like Imperial Airways (British state carrier), that played a key role in connecting their colonial empires with their headquarters; these airlines were initially subsidized by their respective governments.Footnote 21 Commercial aviation was a highly regulated industry in the 1930s to ensure safety and stability and proliferated in Europe and North America, which possessed the capital, advanced aviation schools, and infrastructure to serve military, postal, leisure, and commercial purposes.Footnote 22 McCormack examines the relationship between aviation and colonization in the interwar period and argues that the idea of empire building was central to developing communication and transport infrastructure linking the hinterland territories and their respective colonial occupiers.Footnote 23 For instance, Britain prioritized air transport links to India and later to British African territories.Footnote 24

After the end of World War II, some of the European powers extended the aviation industry to their imperial territories in Asia and Africa to serve colonial interests such as surveillance, business, and tourism and as symbols of technological advancement and power.Footnote 25 The development of air transport provided fast and convenient connection to the hinterland and eased mobility of goods, services, and settlers in the colonial territories.Footnote 26 The British aviation model could be juxtaposed with other European powers such as Portugal, Belgium, and France, which preferred serving the colonies with their national carriers rather than developing autonomous air transport. In the African context, Britain established multi-flag carriers in colonial territories, where some operated in the post-independence eras, and the reasons for their failure have been examined.Footnote 27

Deregulation of airlines commenced in the 1970s, followed by series of bilateral agreements between the United States and European countries that paved the way for liberalized air services and the emergence of competitors in previously protected routes.Footnote 28 Open-sky policies in air transport expanded to all other regions. In the 1990s, the airline industry experienced what Doganis refers to as “the distressed state airline syndrome,”Footnote 29 as the majority of state-owned airlines in Europe required state capital injection to stay afloat after the oil crisis that resulted due to the Gulf War in 1991.Footnote 30 The wave of privatization of state-owned airlines was prevalent in the 1990s to make them competitive. Although still underdeveloped compared with the rest of the world, the aviation infrastructure and capacity in the African context has improved since the 1960s. In 1960, about seventeen state-owned airlines were operational, with a similar number of commercial airports. By 2018, the number had escalated to 352 commercial airports and 198 airlines that carried 115 million passengers in that year.Footnote 31 Between 1970 and 2019, the African continent accounted for 2 percent to 4 percent of the global passengers carried annually, although the absolute figures increased from 6.42 million in 1970 to 31.56 million in 2000 and 100.43 million in 2019.Footnote 32

Aviation in East Africa was formed in this context as a collaborative project of the colonial governments of Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania. Cooperation between these three colonies dates to the late nineteenth century when they formed British East African territories, each under a colonial governor (the three governors formed the East African Secretariat in 1926). In the 1920s and 1930s, the East African Secretariat coordinated the establishment of a unified currency, a common market, a common education system, and infrastructure to bring this vast region under firm imperial hegemony.Footnote 33 Transport infrastructure and services such as postal, harbor, and railway networks were centralized, precipitating the formation of regional corporations that required centralized management.Footnote 34 The aviation industry emerged as a crucial avenue for establishing communication and transport links between the colonial territories and imperial headquarters.Footnote 35

The aviation industry in East Africa was pioneered by a Briton, Florence Wilson, who established the privately owned Wilson Airways in July 1929.Footnote 36 Wilson flew from England to Kenya in a Fokker Universal (VP-KAB). She identified a market gap and invested capital in developing an airline that would serve the settlers in the East African region. The initial services included delivery of airmail and chartered transportation to rural settlements. By 1939, Wilson Airways connected the Nairobi, Mombasa, Dares Salaam, Zanzibar, Kisumu, and Lusaka routes. Despite facing stiff competition from imperially backed South African Airways, Wilson Airways operated for over a decade without any accidents or subsidies until it was wound up during the war in 1940. The colonial government took control of Wilson Airways’ routes, assets, and airports during the war, using them as bases for Royal Air Force military operations, and then the airports operated as noncombatant airfields after the war ended. In the post–World War II period, the East African Secretariat and British settlers played a crucial role in the formation of EAAC. They were extremely zealous about air transportation and urged Colonial Office Headquarters to develop a plan for local air transportation services like those they had experienced through Wilson Airways. In return, Colonial Office Headquarters sponsored feasibility studies that led to the creation of the EAAC.Footnote 37

East African Airway During the Colonial Era (1946–1959)

The East African Territories (Air Transport) Order in Council was established in 1945, paving the way for the EAAC’s formation later the same year by the British Territory and Colonial Office in London.Footnote 38 Sir Charles Lockhart was appointed the first chairperson of EAAC, and the multistate carrier commenced operations in 1946 under the East African Secretariat as a scale alliance comprising the Colony and Protectorate of Kenya (68 percent), Protectorate of Uganda (23 percent), and Tanganyika Territory, including Zanzibar (9 percent).Footnote 39

EAAC was established with an initial capital outlay of £50,000. The entity expanded and diversified its routes over the years. Operations commenced with a fleet of six Dragon Rapide aircraft that were hired from and operated by the British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC), with the maiden flight following the regional Nairobi–Mombasa–Dar es Salaam route. The multistate carrier was operated by the British ruling class and headquartered in the Eastleigh airbase in Nairobi. EAAC established its raison d’être through expatriates with a global view that connected British territories beyond the region. BOAC was responsible for providing technical assistance and recruited twelve expatriate pilots to operate EAAC. In 1946, it carried 9,403 passengers and incurred a loss of £25,483.Footnote 40

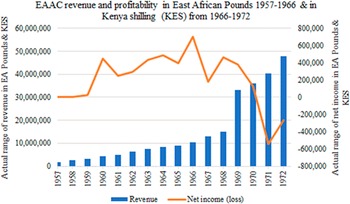

The imperial government established the East African High Commission (EAHC) in 1948 to oversee and manage common regional transport, communication, and educational services such as railways, airways, harbors, and universities. EAHC also introduced common tariffs to generate funds from the subjects. In 1949, the colonial governments raised £221,500 in additional capital to link regional towns and international route networks such as Nairobi–Salisbury–Mbeya and Nairobi–Durban–Dar es Salaam–Blantyre in 1950, and further extended to Ghana, Nigeria, India, Hong Kong, and other British territories by 1957.Footnote 41 In 1950, the firm’s revenue was £1.1 million, with 49,000 passengers flown. By 1960, the numbers had increased by 295 percent and 206 percent to £4.34 million and 150,000, respectively.Footnote 42 EAAC was therefore a growing business generating profits (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. EAAC’s actual revenues and profits between 1957 and 1972.

Source: Kenya National Archives EAAC reports for various years (compiled by the authors).

However, despite this expansion, aircraft technology advanced in the late 1950s, and higher-capacity U.S.-made Lockheed aircraft replaced the Dragon Rapides, which necessitated the construction of bigger hangars and runways and better maintenance equipment. The deployment of this aircraft technology in Africa initially faced limitations, such as inadequacy of technical skills, communication barriers, and the geographic landscape.Footnote 43 Workforce training took place to meet these challenges, as well as challenges surrounding the overall expansion of the company. EAAC needed not only more employees, but also employees with specific skills.

Recruiting and Training the Local Workforce

The workforce was continuously trained to keep up with the advancements in technology, and the long-term panacea entailed involving the local workforce in the airline. By 1953, EAAC had a total workforce of 900,Footnote 44 which increased to more than 1,500 by 1960 (see Table 1). To recruit locally, the company circulated details of vacancies and the qualifications required to all schools in the British East African territories. Progressive training of existing staff continued in parallel with recruitment.Footnote 45 In 1959, the chairman of EAAC, Sir Alfred, explained:

To enable the corporation to implement its staffing policy, the essentials are that there should be an adequate number of suitable local candidates with suitable educational qualifications up to the School Certificate and above, and that adequate facilities should be available for continued training such as that provided by the Technical Institute in East Africa or at the specialized institutes in the United Kingdom. To this end, discussions have been held with the East African Common Services Organization, who has indicated that the governments will assist the corporation in finding suitable personnel for training. The corporation will liaise with the Territories by keeping them advised of vacancies and the qualifications required.Footnote 46

Table 1. Breakdown of origins of EAAC staff in 1960 in numbers

Source: EAAC internal reports, Kenya National Archives, East African Airways Corporation Papers, Nairobi.

EAAC employees’ housing and transportation challenges were addressed to ensure they could conveniently undertake their duties. As Sir Alfred noted, the corporation worked in conjunction with the County Council of Nairobi to develop EAAC staff housing at the Embakasi Village (adjacent to the airport), with the first phase completed in September 1959 and the second in February 1960.Footnote 47 Because the British East African Territories lacked advanced infrastructure suitable for such training programs, the EAAC collaborated with partners such as the British Aircraft Corporation and Rolls Royce in the United Kingdom, Lufthansa in Germany, and the BOAC training center in India.Footnote 48

The management’s stance was that no course of instruction, however well conducted, could replace steadily acquired experience, which enables one to assume responsibility for making decisions. All technical personnel were required to hold qualifications or licenses, most of which were obtained only after long periods of training and experience. For example, pilots were required to have ten to twelve years of flying experience in conjunction with robust training to qualify as a Comet aircraft captain. EAAC used the following criteria to identify and match local candidates with suitable roles:

-

1. identification of jobs suitable for accelerated localization;

-

2. reorganization of jobs with Africanization in mind;

-

3. recruitment and selection of suitable candidates; and

-

4. planning training programs.Footnote 49

As a result of the advent of the jet age, with the consequent trend from piston aircraft to turboprop and pure jet, changes in the character of international air services—such as fares and training—were implemented. Crew training continued under the supervision of flying instructors, check pilots, and examiners, who were all senior captains specially selected for these important duties. The competency of the operating crew was maintained and improved, and flying, training, and type conversions were carried out with efficiency and as economically as possible. Demonstrations and instructions of emergency procedures and drills were again a feature of the yearly training program.

The company’s management, dominated by British nationals, demonstrated a clear commitment to basing the company’s growth on the engagement of Africans. How was this goal achieved? The EAAC archives hold only a few documents containing details of the entire workforce. The oldest document is an internal staff survey from 1960 (see Table 1). Gender and racial disparity were important issues. Top-level roles such as flight crew were entirely the preserve of male Europeans. Female Europeans dominated the sales and reservation roles, which were also open to Asians and Africans. Male Africans occupied low-ranked roles in engineering, stations and traffic handling, accounts, management, and administration positions, which accounted for 42 percent of the total workforce. The female African workforce was inexistent except for one assigned the management and general administration position, in contrast with female Europeans and Asians who constituted 8 percent and 2 percent of the total workforce, respectively. The near absence of African women is also a result of gender inequality in education and access to the labor market. In traditional African societies, women were not educated to take a job, but to take care of the family.Footnote 50

Most of the Asian men, probably from India, were engaged in engineering and station and traffic management, positions similar to those of the Africans. This suggests that the company’s management found it difficult to recruit only locals for these positions. The recruitment policy thus reveals a bipolarization between aircraft crews composed mainly of Europeans and ground crews employing mainly Africans and Asians. The highest-paid positions were clearly given to Europeans.

End of British Rule and Africanization of EAAC (1960–1977)

In 1960, the decolonization process gained momentum, and the British were preparing to hand over the operations of EAAC and other entities to the new governments, albeit in a piecemeal manner. All along, the corporation was run with a control rationale without much thought given to long-term succession plans. The three states of Tanganyika, Uganda, and Kenya attained their political independence in 1961, 1962, and 1963, respectively.

Tanganyika was willing to delay its independence if that meant the British would grant independence to the triad states concurrently, and Tanganyika’s leader Julius Nyerere was keen on forming a regional federation that would continue overseeing operations of the joint entities. The EAHC was still seen as a colonial instrument, but following the independence of Tanganyika in 1961, the East African Common Services Organization (EACSO) was established that same year to replace EAHC. EACSO was overseen by the Common Services Authority, which was chaired on a revolving basis by the three heads of state, although Kenya and Uganda were still under colonial rule. The ministerial committee was responsible for the administration of EASCO. It was composed of ministers for social and research services, finance, labor, commerce, and industrialization, who agreed that all net cash surplus of operational costs in the regional corporations must be remitted to headquarters for reallocation to development and recurrent expenditure.Footnote 51 During negotiations for the independence of Uganda and Kenya, the British government pressed for continued involvement through the Royal East African Navy (an arm of the EAHC), but Tanganyika opposed the move, citing that it would contravene its sovereignty and arguing the need to create an autarkic economy devoid of influence from its former colonial power. This resulted in the dissolution of the Royal East African Navy.

Growth of EAAC Under African Management

The formation of the EASCO paved the way for the establishment of the East African legislative council that passed laws to facilitate the transfer of ownership of joint-owned entities such as EAAC from the colonial government to the newly independent states. EAAC’s shareholding after independence maintained the status quo, with the government of Tanzania (including Zanzibar) holding 9 percent, the government of Uganda, 23 percent, and the government of Kenya, 68 percent, until 1965, when BOAC injected capital equivalent to 53 percent. Consequently, with the arrival of a new investor (BOAC), East African government participation was diluted in the new capital structure, with Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania holding 32 percent, 11 percent, and 4 percent, respectively. In 1970, the departure of BOAC (for reasons discussed later) resulted in an equal shareholding of 33.3 percent among the three East African governments. EAAC continued recording an impressive financial performance. In 1960, gross sales stood at £4.34 million and reached an apex of £14.89 million in 1968 before dropping to £4.74 million in 1973 (sales data were unavailable from 1974 onward) (see Figure 1).Footnote 52 This was equivalent to 243 percent growth and a 68 percent drop, respectively. As for net income, it was always positive during the 1960s, and the first deficit appeared in 1971. The decline in revenues resulted from the withdrawal of credit facilities by the local banks in 1971, which left the airline unable to procure spare parts and other supplies necessary for supporting effective operations. The passenger segment, which had recorded traffic of 150,000 in 1960, grew to 421,989 in 1968 and 553,800 in 1973.Footnote 53 In addition to the expansion of regional routes to include Zanzibar–Pemba–Dar es Salaam, the international routes Dar es Salaam–Rome and Nairobi–London–Rome were launched in 1960 and 1973, respectively, and the Kinshasa, Cairo and Seychelles, and Dar es Salaam–Peking routes were extended in 1975. Benchmarking against the best in class in 1969—including Japan Airlines, Trans World Airlines, Scandinavian Airlines, Air Afrique, Ethiopian Airlines, and Air Congo—reveals that employee productivity measured by available tonne-kilometer per employee was 57 for EAAC, compared with 240 for top performer Trans World Airlines (see Table 2). However, this was still low compared with the other international airlines.

Table 2. Airline Productivity per employee-Selected IATA Carriers for the year 1969

Source: KNA/Rv/9/28, 1969.

Abbreviations: SAS, Scandinavian Airlines; TWA, Trans World Airline.

The year 1971 was difficult for EAAC, as it encountered financial challenges. Stiff competition from chartered operations across all routes led to reduced revenue and high fixed costs that could not be managed by downscaling operations, and was compounded by unsustainable variable costs whose major component—fuel cost—escalated due to its coincidence with the onset of the oil crisis.Footnote 54 These operational hiccups were further compounded by the 1971 coup d’état in Uganda, and the member states ceased remitting funds from regional corporations, thus stifling the smooth operation of EAAC until 1977. Although financial data are not available for the years 1973–1977, the company was definitely losing money.Footnote 55

Training African Employees

The 1960s was a decade of rapid growth for the company. The total number of employees grew to more than 4,300 by 1969 (see Table 2). However, the main concern was not the increase in the workforce itself. The management of EAAC was predominantly British, and the new governments called for accelerated Africanization, despite the states being ill-equipped with respect to skilled labor forces and resources. EAAC incurred training costs on the local workforce to bridge the skill gaps. Sir Alfred Vincent held the chairmanship of EAAC from 1949 until December 1964. In 1965, Chief Abdullah Said Fundikira (who had served in the ministries of water and justice in Tanzania and was a graduate in agriculture from Makerere University) and Wilson Kyobe took over as president and managing director, respectively.Footnote 56 They were the first Africans to hold such high positions. Job opportunities in EAAC were shared equally among the three states.Footnote 57

The appointment of senior managers and aircraft crews also followed the principle of Africanization. For example, Elijah Ochieng Kammayoyo was the first African pilot and aeronautical engineer for the EAAC.Footnote 58 He trained at Seafield in England and returned to fly in 1959 in colonial Kenya. He began flying small DC aircraft in Tanzania, Uganda, Sudan, Congo, and South Africa, while gaining international experience. Moreover, in 1966, a graduate African engineer was appointed purchasing and stores manager, and the positions of executive recruitment officer, personnel manager, and housing officer were also Africanized.Footnote 59 Among other duties, the executive recruitment officer was responsible for visiting secondary schools and university colleges in East Africa to alert graduates to career possibilities at East African Airways and attract talented individuals to the company. Finally, the Africanization of EAAC was accelerated even in overseas offices, such as in London, where most clerical jobs were offered to Africans.Footnote 60 The training of African employees targeted three major activities.

First, the formation of a team of African pilots was a major objective of the firm. Four African Comet crews (pilots) completed their training at the beginning of 1962 in preparation for increased UK schedules, which commenced in April. The Comet crews’ biannual checks were taken on the BOAC simulator at London Airport. All other training was undertaken in East Africa. By the middle of the year, arrangements were made to train pilots for the Friendship aircraft (a type of Dutch aircraft manufactured by Fokker). The first four African Friendship captains underwent training in Amsterdam, but all subsequent training—ground and flight—was undertaken in East Africa. In addition, there was the usual large-scale conversion training that resulted from the promotion of pilots from one fleet to another due to the expansion of operations. Considerable thought was given to the type of synthetic training most suitable to the corporation’s needs, with orders placed for one flight trainer for Friendship aircraft and another specially designed for training for Comets on the Smith Flight System.Footnote 61 In 1963, there were other courses for management teams consisting of flight and cabin crews. Nairobi Airport housed a Cabin Service Training Centre for recruits who assumed flight attendant duties aboard aircraft. An additional sixteen male and five female African staff were trained and handled various service operations. EAAC and the governments of the three partner states met the costs of young East Africans training to become pilots. At the end 1967, there were twenty-five Africans training at the Embry Riddle Aeronautical Institute in the United States and six at the Oxford Air Training School and three at Airwork Services Training in the United Kingdom.Footnote 62 Due to the high turnover of expatriates in the 1970s, continuous training of Africans in flight navigation courses to obtain a commercial pilot license for the EAAC’s four aircraft types (SVC1.0, DC9, F27, and DC3) proceeded in partnership with organizations such as the Danish Civil Aviation School and aviation schools in the United Kingdom. For instance, in 1974, fourteen graduated as captains and another seven qualified as first officers.Footnote 63

Second, EAAC actively engaged in training African sales and marketing staff. The company was highly dependent on international routes and agency business for its viability and therefore had to maintain international competitive standards in its dealings. This presented recruitment problems, as the firm had to recruit those best suited to airline work. In 1963, a total of forty Africans were recruited to join the sales and traffic departments and were trained at the EAAC Commercial Training Centre in Nairobi by the firm’s experienced staff for possible promotions to the assistant grades. A higher success rate in recruiting African officers to work in the international relations and sales dockets was achieved.Footnote 64 The sales training booklet included the basic principles of engaging people and offering courteous and efficient services. Sales and marketing aimed to project the Safari image, EAAC as the Safari airline to the preferred Safari region with beautiful coast, mountains, and game parks favorable for holiday experiences.Footnote 65 The Commercial Training Centre was considerably enlarged, and the commercial training manager had four instructors to assist with the training courses for existing commercial staff and new recruits. Courses were interspersed with periods of practical on-the-job training to achieve the best results. During the year, courses covering induction, sales, weigh bay procedures, aircraft documentation, reservations, and ticketing, as well as refresher courses, were attended by 240 commercial staff. In accounting, wholly on-the-job training was carried out within the firm. However, staff were encouraged to attend evening classes at the Kenya Polytechnic and other centers on bookkeeping and allied subjects, and arrangements existed for assistance with fees upon satisfactory completion of courses. Africans made up two-thirds of the accounting department, and opportunities for accelerated promotion were provided to staff who exhibited potential for development.Footnote 66 In 1972, the EAAC entered into a management services agreement with Eastern Airlines in the United States to second up to nine EAAC staff members as needed. That same year, Eastern Airlines staff were seconded to serve as technical advisors, financial controllers, and marketing managers at EAAC.Footnote 67 Some African Americans at Eastern Airlines were pioneers in holding leadership positions in corporate America in the 1960s and 1970s. One notable example is James O. Plinton, the first black person to be appointed to the top management of a national airline in the United States. He assumed the role of executive assistant to the director of personnel and industrial relations at Eastern Airlines in 1957 and was responsible for hiring African American flight attendants.Footnote 68 He was part of the group of personnel seconded to EAAC by Eastern Airlines and was instrumental in recruiting the first group of African pilots for EAAC.Footnote 69 The cooperation between Eastern Airlines (a U.S., not a British, company) and EAAC may be due to the proximity of the seconded personnel in terms of corporate culture, with both African American and African executives taking pioneering roles.

Third, the formation of engineers for the maintenance of aircraft was the last major target of EAAC Africanization. Engineer training was initially conducted through an apprenticeship program. In 1963, eight of the sixteen engineer apprentices were African students being trained at Air India’s maintenance base, which offered to train more African candidates annually when they were recruited.Footnote 70 In 1974, the academic-based apprentice program was dropped in favor of a more practically oriented curriculum to produce licensed engineers and supervisors with on-the-job training experience, utilizing facilities of the Flying School at Soroti, Uganda.Footnote 71 Moreover, in the same year, several training courses for EAAC African engineers were conducted, such as avionic training at the Ethiopian Airlines training school in Addis Ababa and supervisory and instructional technique courses were conducted at the International Civil Aviation Organization training school in BeirutFootnote 72

In 1966, the scheduled introduction of the Super VC (British-made aircraft suitable for operating across long distances and landing on short runways) required the inception of a considerable conversion program. Senior captains and first officers from the Comet fleet attended courses arranged by the manufacturer in the United Kingdom, which subsequently necessitated training more Comet pilots and recruiting more pilots as aircraft replacements for the domestic fleet continued. The Super VC training was completed on schedule, and the aircraft entered service with fully trained African crews.Footnote 73 The commercial department was critical for revenue generation and was targeted for localization of management-level positions in 1967. As noted in EAAC’s 1967 report by the general manager Wilson Kyobe:

The growth of the commercial department which is an urgent target for Africanization programme has been such that the intake of new staff and their training, in addition to providing replacements for trained and partially trained staff who leave for higher education and other reasons. A continuous recruitment process of calling forward, aptitude testing, interviewing, and selecting applicants produced 423 new commercial staff during the year. In 1966, positions such as sales office superintendent, Kampala; assistant manager, Uganda, assistant manager, Tanzania; staff travel officer; public officer; assistant to area sales manager (East Africa), assistant to the commercial planning manager and assistant passenger handling instructress were filled by Africans.Footnote 74

Results of EAAC’s Africanization Policy

Human resource development by the newly independent EAAC was set up in a sensitive context. There was political pressure to promote African employees. For example, in 1963, the Transport and Allied Workers Union was vocal in agitating for Africanization; training African pilots; and improving employment terms such as bonuses, holidays, and special uniforms.Footnote 75 Conversely, the company’s management attached importance to meritocracy to ensure its efficiency and profitability. In 1961, EAAC chairman Sir Alfred expounded this position:

It has been the Corporation’s policy and practice to recruit staff from within the East African Territories whenever candidates who possessed suitable qualifications could be found, but due to rapid expansion of the corporation’s activities it has at times proved impossible to recruit staff locally due to lack of sufficient experience to fill the posts necessary to maintain this rate of expansion. The training organization now set up is designated to produce in the course of time trained personnel, particularly Africans of the required caliber.Footnote 76

Moreover, the new East African governments were conscious of their dependence on foreign partners, especially knowledge and technology transfer. In 1963, Kenyan president Jomo Kenyatta and the minister of planning and economy Tom Mboya opined that foreign and private capital were crucial instruments in the country’s quest for creating job opportunities in the long run, and Africanization was of secondary importance.Footnote 77 This was echoed in 1963 by the minister of labor in Tanzania, Michael Kamaliza, who stressed that “we need overseas investment, and we shall not get it if we nationalize. It would just frighten everybody away.”Footnote 78

In the case of the aviation industry, it was not only the investment of foreign companies that had to be safeguarded, but their willingness to cooperate technically with EAAC. In fact, the company remained state-owned and the collaboration with BOAC was mainly carried out without taking any capital, except for a short period between 1965 and 1970, when BOAC acquired a short-lived stake of 53 percent. BOAC’s capital injection was directed toward acquiring more aircraft and strengthening its partnership with EAAC beyond technical assistance to support route diversification and expansion strategy. In 1970, the United Kingdom began implementing major aviation industry restructuring reforms contained in Ronald Edward’s report “British Air Transport in the Seventies.” Therefore, the East African governments’ buyout of BOAC’s stake in 1970 could be seen as a strategic move to finance BOAC’s takeover of the British United Airways group (a large independent airline) whose market prospects were negative under the new legislation.Footnote 79

Hence, it was practical to opt for moderate nationalism to avert foreign capital flight.Footnote 80 The localization policy had several impediments, as the general manager of EAAC Captain P. A. Travers captured in 1961:

The corporation recognizes the need for localization of staff as quickly as is predictable, and has set up a Commercial, Engineering and Accounts Training Scheme. Details of vacancies were circulated to all schools. At the same time, progressive training of existing staff continued. It will be recognized that the more senior posts in any airline must be occupied by persons of many years specialized experience, such as can only be acquired in the highly developed countries. Experience of this kind gained in the ordinary course of employment, is not available on a sufficiently large scale in the East African territories, and it is this deficiency that our training schemes, which will be conducted by experienced and specialist staff of the corporation, seek to remedy.Footnote 81

Thus, during the 1960s, the Africanization of EAAC’s recruitment included a meritocratic dimension, in the sense that the company valued the training and ability of its local employees, not just their origin. It was necessary to guarantee international standards, not only for the firm’s own operations, but also to ensure collaboration with external stakeholders, such as BOAC. Initially, only junior positions were given to the qualified workforce, as Sir Alfred noted in 1964:

Much has already been done in employing African trainee passenger assistants at main stations, as stewards, and stewardesses on the aircraft. Training courses for reservation, counter and traffic assistant are in constant progress. Success depends on attracting candidates of a higher education standard than have been forthcoming in the past, while giving the existing staff the opportunity to improve their positions. At the same time, it can be but recognized that the corporation must in the public interest seek to maintain the highest international standards, most of which are prescribed by law.Footnote 82

The senior management positions required qualified and internationally experienced staff, and few Africans met these criteria. Moreover, the board and executive positions were offered through clientelism and patronage, as demonstrated by the appointment of the first Africans into those positions (see “A Competitive African Airline Company”). The meritocratic policy implemented by EAAC after decolonization negatively impacted Africanization during the first years of operation. Table 3 shows that Africans represented 34 percent of the total workforce in 1965, against 44 percent in 1960. EAAC gave priority to qualified staff, regardless of their origin. The senior managerial positions of flight and cabin crews were dominated by Europeans (mostly British personnel), accounting for 8 percent of the total workforce. The same positions were opened to qualified Africans (1.3 percent) and Asians (1.1 percent), although the flight crew was male dominated across the board. Male Asians dominated the engineering, stations, and traffic-handling positions, constituting 35 percent of the total workforce; Africans in similar positions constituted 26 percent of the total workforce. Female Europeans, female Asians, and female Africans constituted 6.5 percent, 2.0 percent, and 0.7 percent of the total workforce, respectively. The formation of African staff under the training schemes organized by EAAC developed and enabled an accelerated Africanization during the second part of the 1960s. In 1970, Africans constituted 75 percent of the total workforce of 5060, while Europeans represented 12 percent and Asians 13 percent (breakdown of the data by positions was unavailable).Footnote 83

Table 3. Breakdown of EAAC staff by origins in 1965

Source: EAAC internal reports, Kenya National Archives, East African Airways Corporation Papers, Nairobi.

The emphasis on recruiting European personnel was thus used during the colonial period for control purposes, as the initial goal of developing the airline industry was to connect the colonies to imperial headquarters and exclude the locals from executive positions.Footnote 84 Toward independence of the East African colonies, EAAC had begun to appoint more African pilots, managers and general staff, due to political pressure and increased demand for Africanization and local human capital development to replace departing expatriates. The EAAC and governments committed to funding educational programs for African talent, both locally and abroad. Historical notions of uneven development among East African states since the colonial era have placed Kenya in an advantageous economic position relative to its neighbors, leading to sentiments that Kenya benefits disproportionately at the expense of its neighbors when it comes to the operations of common entities such as EAAC.Footnote 85 BOAC had acquired a stake to stimulate the expansion of EAAC in 1965, but eventually sold its interest in EAAC in 1970 for commercial reasons and the political tensions that had built up between the member states. In the same year, in an attempt to resolve recurring control problems among the three member states, an equal share of capital was agreed in the restructuring of EAAC’s capital (33.3 percent each), with Uganda and Tanzania having to inject more capital in return.

The company collapsed in 1977, due to political factors such as the coup d’état of President Idi Amin Dada in Uganda in 1971. It led to the deterioration of relations between the three states. The failure to release funds collected from the joint venture operations for central planning and allocation crippled flight operations, plunging the company into losses and preventing its ability to meet liquidity. Commercial banks stopped extending credit to EAAC, and the company filed for bankruptcy. Three competing airlines emerged (Kenya Airways, Uganda Airways, and Tanzania Airways), the first being the largest. The following section discusses Kenya Airways’ human resources experience.

Human Capital Development by Kenya Airways (1977–2020)

This section discusses the impact of creating a national flag carrier (1977) and the subsequent injection of capital by the Dutch multinational company KLM in 1996 to develop human capital. Because company records for this period are not available, we base our discussion on annual reports and business newspapers. These sources do not allow us to develop as detailed an analysis as in the previous section. They do, however, provide an opportunity to examine the impact of organizational changes after 1977 on the executive recruitment policy of a formerly jointly owned airline. A major issue is understanding whether the formation of KQ led to more intensive indigenization due to the firm belonging to a single state. In addition, we analyze the impact of KQ’s transformation into a joint venture with foreign capital on the human capital development strategy.

State-owned Company (1977–1995)

KQ was established in January 1977 as a national flag carrier to capitalize on the market opportunities left by the defunct EAAC, the increasing number of tourists visiting the country, and MNE employees who were operating from Nairobi. At the formation stage, the firm encountered obstacles such as inadequate financial resources, inexperienced technical staff, pressure to absorb staff, physical assets, and costly external debts of the extinct EAAC.Footnote 86 The company’s senior management and board positions were awarded to political allies who lacked business acumen and expertise, thus plunging the airline into financial turbulence.

For example, Eliud Mathu, who was appointed president of KQ in 1977, had a political career between 1944 and 1957.Footnote 87 Taita Toweett, who served as president from 1983 to mid-1985, was a member of Parliament, minister of education, and minister of housing and social services between 1960 and 1979.Footnote 88 Omolo Okero also had a successful political career between 1969 and 1979 as a member of Parliament, serving in various ministries of health, power and communications, and information and broadcasting. He joined the KQ board of directors in 1991 and was appointed chairman in 1996.Footnote 89 Being a career politician is not in itself incompatible with running a public company. It may even facilitate communication with government and departments. However, these appointments were the expression of a recruitment policy that placed more importance on personal relationships than on managerial knowledge, precisely at the time when the new company needed this expertise. In 1980, the company’s total number of employees was 2,100 and increased by 33 percent to 2,800 in 1985. In 1981, the government appointed Richard Nyaga (a lawyer by training and a graduate of the University of Dar es Salaam and McGill University) to the position of managing director.Footnote 90 He remained in that position until 1985, when he was replaced by Leo Odero, who quickly assumed the dual position of executive chairman and managing director before Fred Neto was appointed managing director the same year, with Odero retaining the other position. Neto’s tenure was short-lived. He was suspended in 1987 and replaced the same year by Joseph Nyaga (who studied economics and political science and was a banker, ambassador, and politician), who remained in office until 1991.Footnote 91

The company recorded a net loss of US$1.3 million and US$130 million for the years 1977–78 and 1980–81, respectively, and a net profit of US$28 million in 1982–83.Footnote 92 It posted a net loss of about US$50 million in the 1991–92 fiscal year, and a net profit of US$16 million in 1994/95.Footnote 93 In terms of profitability, KQ went from a loss-making situation in 1977 and for a few years in the 1980s to low profitability and losses in the early 1990s (see Figure 2). The number of passengers flown annually rose from 356,894 in 1978 to 402,566 in 1980, 559,997 in 1985, 643,398 in 1990, and 1,800,000 in 1995, demonstrating increases of 13 percent, 39 percent, 15 percent, and 180 percent, respectively. Despite the impressive increases in passenger numbers, KQ reached the nadir of its financial performance in 1993–94 when it recorded a net loss of US$30 million, but political goodwill and subsidies kept the company afloat. The company became a drain on public resources, and privatization was deemed the only solution to make the company operationally sustainable.Footnote 94 Evidently, the appointment of locals with no business acumen and experience was detrimental for KQ.

Figure 2. KQ’s net income and sales turnover in US$ (thousands) for 1990–2017.

Source: Kenya National Archives, Kenya Airways annual reports for various years (compiled by the authors).

In 1990, the Kenyan government contracted Swissair AG for two years to assist in realigning the flight operations, information technology, marketing, and customer care departments of KQ.Footnote 95 In 1991, the process was fast-tracked when Speedwing Consulting, a subsidiary of British Airways, was appointed as the advisor on business restructuring. It recommended introducing financial controls, maximizing fleet utilization, reviewing routes’ revenue generation, reorganizing the company’s balance sheet, and a new management framework.Footnote 96 These issues necessitated the appointment of a new management team by the government to implement the changes, followed by commercialization and privatization of the companyWhen KLM took a stake in the airline, it provided capital and management knowledge to support the firm’s development.Footnote 97

A Competitive African Airline Company (1996–2020)

Privatization of KQ took place in 1996. KLM acquired 26 percent equity for $26 million, including a technical assistance deal; institutional investors acquired 28 percent; the public bought 20 percent; employees were allotted 3 percent equity; and the Kenyan government retained a minority of 23 percent.Footnote 98 This acquisition allowed KLM to nominate two directors to the KQ board and gave it the discretion to nominate candidates for managing director and finance director positions. KLM’s first board nominee Robert J. N. Abrahamsen, the managing director and chief finance officer of KLM, had a background in economics and twenty-five years’ experience as the chief executive of the Nedbank Group in South Africa.Footnote 99 The second board nominee was KLM’s executive vice president of passenger sales and services, Andries B. Van Luyk. His background was also in economics and he had held regional manager, area manager, and senior vice president of field organization positions in KLM across twenty-five year.Footnote 100 In the same year, KLM trained all of KQ’s pilots, offered new computer systems as a technical assistance package, and formalized the marketing alliance.Footnote 101 These measures were crucial for human capital formation in KQ.

The number of KQ employees decreased by 3 percent from 2,860 in 1990 to 2,780 in 2000. However, in FY2010–11, KQ’s total workforce was 4,355, and by the end of 2020, this number had decreased by 16 percent to 3,652 due to a gradual streamlining of staff. Again, we do not have details on the origins and educational backgrounds of the entire workforce. However, the profiles of executive directors appointed since the early 1990s illustrate a desire to emphasize management expertise rather than ethnicity. Brian Davies (a former general manager of British Airways) was the managing director from 1992 to 1999.Footnote 102 He instituted changes in organizational structures, reoriented the company’s strategy toward customers, and returned the company to profitability. These radical changes minimized government interference in the company’s affairs and led to transparent recruitment and the posting of available positions on public boards.Footnote 103 Davies was succeeded by Richard Nyaga (former managing director of the aforementioned state-owned KQ), who held the position for four years until 2003, when Titus Naikuni (engineer, former managing director of Magadi Soda Company and Magadi Railway Company) was appointed.Footnote 104 Upon Naikuni’s retirement in 2014, KQ’s COO Mbuvi Ngunze (with a background in accounting, he was the former CEO of Group Internal Communications and CFO of Lafarge) was named managing director.Footnote 105 Finally, in 2017, Sebastian Mikosz (former CEO of Polish Airlines with a background in economics and finance) became the second foreigner to serve as CEO of KQ.Footnote 106 He was appointed in 2017 after a recruitment process finalized by Spencer Stuart, a U.S. executive and leadership consulting firm. These appointments show that KQ’s top-level recruiting focused on experience and ability, rather than ethnicity. An interesting observation is the absence of women in all of these top-level hires.

Between 1996 and 2007, the company recorded an upward trend in sales, and the operating revenue increased 301 percent, from US$29 million in 1996 to US$63.8 million in 2007. Passenger numbers grew by 250 percent, from 788,272 in 1996 to more than 1.97 million in 2007. The improvement in financial performance and service levels was attributed to commercialization, training, and joint marketing with KLM.Footnote 107 The firm became more efficient and recorded increased profits over the years until the 2008 financial crisis and recovered in 2010 (see Figure 2). KQ expanded internationally, backed by the acquisition of fifteen Boeing aircraft between 1996 and 2007, and emerged as one of the most profitable airlines in Africa.Footnote 108

Between 2012 and 2017, an ambitious expansion project led KQ to overextend itself to finance the purchase of nine new aircraft. Stockholders bailed the company out several times to preserve job losses and ongoing operations. This was followed by a poor financial performance that forced the government to take on more debt and become the largest shareholder, diluting KLM’s influence over the board’s mandate.Footnote 109 The resignation of Sebastian Mikosz from the chief executive position in 2019 paved the way for the appointment of a local, Allan Kilavuka, who had a business degree from the University of Nairobi.Footnote 110 Before this appointment, Kilavuka was the managing director of KQ’s subsidiary, Jambojet, a low-cost airline. Previously, he had been head of General Electric (Africa) and held various positions at Deloitte Africa. This marked the beginning of KLM’s withdrawal from the joint venture, followed by the replacement of expatriate staff who were assisting in the turnaround with local staff that climaxed in a mutual agreement in December 2020 to officially terminate the twenty-five-year joint venture in early September 2021.Footnote 111 The renationalization of KQ meant that the government was not satisfied with recruitment of executives that gave foreigners preference over local managers.Footnote 112

Discussion and Conclusions

This paper sought to examine human capital management since World War II and how this policy changed over time in the airline companies in East Africa. It also explored how human capital development was accomplished and to what extent Africanization was a political objective. Our findings indicate that localization was more than a mere political façade with an elaborate long-term view of producing experienced human capital for anchoring the development of the aviation industry in the East African region. After the formation of EAAC in 1946, all top positions were occupied by European expatriates because organizational development and filling technical positions were critical for control and bridging skill gaps in the firm until local personnel could be trained.Footnote 113 Toward the independence of East African states in the late 1950s, EAAC switched to a staffing policy of employing local personnel in all areas, including management and flight crews. It initiated Africanization schemes by training the local workforce at the company’s cost locally and abroad for roles in the company.

The management of EAAC maintained that indigenization would require locals absorbed into the company to possess sufficient educational qualifications and industry experience to maintain the airline’s international standards. The East African states adopted moderate Africanization that facilitated a smooth transition from a colonial to a postcolonial era, averting interference with the company’s financial performance and foreign capital flight from the region. This can be contrasted with the nationalization that was witnessed in some industries in Nigeria.Footnote 114 After independence in the early 1960s, the East African triad tasked the EAAC with identifying local talent from universities, paying for their training overseas, and placing them in international duty stations to gain experience in operations and management of airline business as a way of preparing for smooth indigenization. The training of African pilots, engineers, and managers was carried out in cooperation with foreign organizations, mainly in Europe and the United States, which provided technical education. The lack of local training centers could have been a weakness in the implementation of the Africanization policy. EAAC management solved this problem by looking outside for the necessary knowledge. An interesting feature in the EAAC’s human capital development is the gender imbalance, especially the local workforce in the colonial era, with only a single female employee in 1960. While there were deliberate efforts to accelerate indigenization between 1960 and 1965, senior managerial positions were occupied by male Africans who had political connections, and females were altogether overlooked. The localization policy went beyond what was outlined by Decker as a political simulation and developed a local workforce that facilitated the establishment of three national airlines after the collapse of EAAC in 1977.Footnote 115

Unlike Air Afrique, the multi-flag carrier in the former French colonies, whose demise was due in part to Africanization, EAAC collapsed for other reasons.Footnote 116 In East Africa, the deterioration of relations between the three owner countries is the main factor that led to bankruptcy. KQ emerged as one of the state-owned enterprises and had to absorb the local staff of the defunct EAAC.Footnote 117 The firm initially appointed qualified and experienced executives regardless of their origins. However, by the mid-1980s, clientelism became widespread, and political cronies lacking business acumen were given the top managerial and board positions. Appointment of former politicians was not uncommon in companies, but the reasons for their nomination and the measures of state intervention in the firm over the years were a matter of concern, such as constant bailouts without change of management. This shortcoming of Africanization of the board through patronage plunged the airline into losses in the late 1980s and early 1990s, leading to privatization of the airline for efficiency and expertise purposes.

KQ and KLM entered a joint venture, and KLM offered technical assistance by training all the pilots and providing new computer systems to build the capacity of KQ’s human capital. This was in return for two board positions, which were powerful enough to overturn the decisions of the other nine members. KQ became one of the most profitable airlines in Africa, and recruitment favored a mix of local and expatriate staff. From 2012 onward, a combination of disastrous board decisions and failed attempts of organizational turnaround led by expatriate management resulted in the dilution of KLM’s equity in 2017. The government of Kenya commenced plans to renationalize KQ, again favoring the recruitment of locals in senior managerial positions to replace expatriate staff.Footnote 118 KLM consequently commenced withdrawal from the joint venture that materialized at the end of 2020 and was finalized in December 2021.

Beyond the case of the aviation industry in East Africa, this research contributes to the literature on indigenization in business history. It has three main implications for future research. First, as noted in the “Introduction,” most academic work on this topic has focused on foreign multinationals in Africa and Asia, emphasizing that indigenization was primarily used to legitimize continued operations in newly independent countries. Our study focused on a state-owned company, owned by the colonial government until the 1960s and then jointly by three independent states. We thus proposed an analysis of indigenization from an African perspective. The challenges were not in adapting to a new institutional environment in order to continue business in a former colony, as the literature points out, but in acquiring the necessary management skills. In the case of the airline industry in East Africa, this was largely achieved through cooperation with foreign organizations.

Second, Africanization was not a purely local or national issue. It can be understood through a transnational history approach.Footnote 119 As mentioned earlier, the knowledge needed to implement effective indigenization came from outside East Africa. EAAC collaborated with a large number of foreign companies and training centers, primarily based in Europe and the United States, but also in India, to acquire expertise in a wide range of activities. Moreover, these transnational networks were not solely based on knowledge transfer. The cooperation between EAAC and the U.S. firm Eastern Airlines during the 1970s also had a strong ethnic dimension, with both companies promoting black people to management positions. Levy has recently demonstrated the importance of interrelationships between Africa and the United States in the global black empowerment movement during the latter part of the twentieth century.Footnote 120 Africanization can be addressed in this transnational context, and further research should focus on indigenization from this global perspective.

Third, and finally, our study has shown that indigenization has a gender dimension that remains largely unexplored.Footnote 121 Our study suggests that this policy, no matter whether it was implemented by the colonial government or the independent states, focused first and foremost on men. However, due to source limitations, as is often the case when attempting to write a history of gender,Footnote 122 it has not been possible to conduct a detailed analysis of the place of women in Africanization.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to three anonymous reviewers and Andrew Popp, the Editor-in-Chief of this journal, for useful comments that helped improve this article.