1. Introduction

Four hundred and thirty-four witnesses, individuals with unique experiences and stories, testified at the trial of Radovan Karadžić, the former President of Republika Srpska, at the ICTY.Footnote 1 As one of the largest cases in the tribunal’s lifetime, it provides a rather extreme example of the volume of evidence that international judges are tasked with weighing in a single case. Nevertheless, a heavy reliance on oral testimony is one of the defining features of modern international criminal courts and tribunals (ICCTs), in contrast to their only predecessors, in Nuremberg and Tokyo, which strongly depended on written documentation.Footnote 2

The magnitude of oral testimony at the modern ICCTs can be explained by three sets of inter-related factors: (i) contextual (i.e., historical and socio-political circumstances, in which the ICCTs operate); (ii) institutional (i.e., prosecutorial and judicial policies and choices); and (iii) case-related. Firstly, the significance of witness testimony is shaped by each ICCT’s specific political and historical context. In certain circumstances few alternatives to testimonies may exist. The ability to obtain documentary or forensic evidence reduces with, inter alia, increased time lapse between the commission of the crimes and the investigations, lack of record-keeping, or informal perpetrator groups with no official paper trail: all characteristic of international criminal investigations. Here, the significance of state support cannot be underestimated. If state co-operation is lacking, not only do the courts have no access to crime sites, but to (potential) witnesses as well, or their safety cannot be guaranteed. The ICCTs have been operating in contexts ranging from largely co-operative to openly hostile, the relationships changing over time. For instance, each case at the ICC to date concerns a separate state, and while some have been largely co-operative (e.g., Cote d’Ivoire, Uganda), others have effectively disbarred the Court from any locally-based investigations (e.g., Darfur, Kenya). Similar fluctuations in co-operation have taken place in Rwanda and its neighbouring states with regards to ICTR operations,Footnote 3 and between the ICTY and some of the former Yugoslavian republics.Footnote 4 The general support from the international community for the courts has also fluctuated, from widespread optimism during the first decade of operations to growing disillusionment in the more recent years.

Next to the ever-changing political and historical circumstances, prosecutorial and judicial choices also play an important role in determining the evidence presented in court. In order to ensure fair trials and fair evaluation of evidence, international judges have, at least initially, strongly adhered to the principle of orality and preferred to hear the witnesses live instead of, for example, using their previous testimonies or written statements.Footnote 5 Though a number of rules have been implemented allowing the chambers to exert control over how many witnesses the parties were allowed to call, the willingness to utilize them has not been universal.Footnote 6 Some judges reasoned that hearing and assessing oral testimony is a key task of a trial chamber, and have expressed concerns regarding evaluation of witnesses who do not present their evidence in court.Footnote 7 The parties are also inclined to have their witnesses appear on the stand, and prefer to have the ability to cross-examine those of the opposing side, as cross-examination provides opportunities to challenge or bolster a given account. Besides, due to judicial preference for oral testimony, both parties would be aware that such evidence might be deemed more persuasive. In addition, the aim of ‘witnessing’ at the ICCTs arguably extends beyond providing information about an offence to exonerate or convict an accused. Live testimonies are also believed to help establish the historical record, to provide a ‘cathartic’ healing opportunity to those who testify, and to ‘give a human face’ to the proceedings.Footnote 8 The pursuit of these big aspirations, complementary to determining the accountability of an accused, could shed light on why thousands of witnesses have appeared before the criminal tribunals.

On top of these contextual and institutional factors, the unique characteristics of the cases tried at the ICCTs are perceived as the main ‘culprits’ behind the actual witness numbers.Footnote 9 International criminal justice scholars and practitioners generally agree that international criminal cases demonstrate exceptional complexity compared to typical serious violence cases adjudicated domestically.Footnote 10 International cases are commonly characterized by a wide temporal and geographical scope of the charges, multifaceted and shifting perpetrator groups, broad victimization, and complexities of international legal constructs. These characteristics then, unsurprisingly, translate into a plethora of facts to be established beyond any reasonable doubt, and in turn dictate the need to secure large amounts of evidence. Combined with the difficulties in obtaining alternative sources of evidence, witnesses become the main avenue available to international investigators.

However, trial observers have long criticized such heavy reliance on live witness testimony, owing to its real or perceived effect on the length of the proceedings.Footnote 11 On average, a case before the ICCTs lasts 4.9 years, and trials, during which the bulk of witness testimonies are heard, take on average 2.9 years.Footnote 12 Such proceedings in practice entail a colossal amount of financial, personnel and time investment, necessary to carry out full investigations and prosecutions, sparking a debate over the tribunals’ efficiency and judicial economy.Footnote 13 At the time of its most intense operations the ICTY, for instance, faced harsh criticism from academics for being too slow and too expensive,Footnote 14 with some commentators questioning the overall ability of international tribunals to conduct so-called ‘mega-trials’.Footnote 15 The scepticism got to its most heated point around the on-trial death of Slobodan Milošević, a former president of Serbia, after the proceedings had been going on for over four years.Footnote 16 It immediately prompted a wide discussion over whether the case could have been managed more efficiently, and what lessons the ICCTs could learn from it. These debates took place among increased political pressures to round off the Tribunals’ activities: in 2003, the UN Security Council adopted the so-called Completion Strategy, which required the ICTY and the ICTR to finish all their trials by 2008.Footnote 17

One of the discussion points in this ‘pursuit of efficiency’Footnote 18 was a possibility of reducing the number of witnesses and the heavy reliance on live witness testimony. Hence, in the hopes of bringing the trials to a more acceptable length, the principle of orality was eradicated from the legal framework of the ICTY. While it remained in the statutory documents of the ICTR, both institutions changed their rules of procedure and evidence (RPEs), giving more room for alternative ways of providing testimony. The most promising among them was ICTY/ICTR Rule 92bis, which allowed a witness to provide his/her testimony by means of a written statement, and not appear at trial, as long as the contents in the testimony did not go to the acts of the accused.Footnote 19 For some critics this reflected judges’ bias against a defendant, robbing him/her of the inherent right to cross-examine a witness,Footnote 20 for others it signalled the overall ‘end of orality’ at the ICTY.Footnote 21 However, in the general context of the pressures for completion of the tribunals’ mandates, the push for judicial economy took the upper hand and arguments calling for a cautious approach and more safeguards for the defence were largely overshadowed.

Consequently, the history of the ICCTs’ relationship to ‘witnessing’ appears to be a constant tug-of-war: Witnesses have been indispensable for the pursuit of international criminal justice, and at the same time, energy was poured into trying to limit their importance and central role. Despite the prominence of witness evidence in international criminal proceedings, empirical legal scholarship has so far neglected this phenomenon. International witness-related studies to date have largely focused on the lived experiences of the witnesses. Researchers have explored individual motivations for testifying,Footnote 22 the experiences of appearing at trial,Footnote 23 and the consequences thereof.Footnote 24 Another strand of witness-related research takes a truth-finding angle, uncovering the evidentiary shortcomings and challenges to fact-finding caused by live witness testimony, e.g., language, trauma, or differences in cultural backgrounds.Footnote 25 No study to date has attempted to systematically and comprehensively map the numbers of witnesses at the ICCTs and analyse the factors that can explain their variation; the existing discussions of the high volumes of this ‘most expensive and time-consuming category of evidence’Footnote 26 are largely based on anecdotes and assumptions.

In this article, we provide new, empirically-based insights into the trends and patterns in the numbers of viva voce witnesses at the ICCTs. Our data comprises information extracted from the trial judgments and other case-related documents issued by the ICTY, ICTR, and ICC. First, we map the numbers of witnessesFootnote 27 across the courts and over time, followed by testing whether complexity factors, pertaining to the characteristics of the cases and the defendants, and efficiency factors, relating to the policies implemented to reduce the numbers of witnesses, can account for their variation. We discuss the findings reflecting upon the historical, political and security contexts in which the ICCTs have functioned. Such evidence-based understanding of what necessitates the high numbers of witnesses is crucial for an informed assessment of the avenues taken to reduce witness numbers, and their effectiveness.

2. Twenty years of witnessing: Facts and figures

As of September 2018 the ICTY, the ICTR, and the ICC have handed down 111 trial judgments in cases of crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide, 19 of them following a guilty plea. In total, the judges have assessed 8,653 viva voce testimonies.Footnote 28 As demonstrated in Table 1 below, the ICTY stands out as the institution that has called the most witnesses both in total (n=5491) and on average per trial (M=125). The variability is also the highest at the ICTY, where the number of witnesses ranges from 12 to 434 in a single case compared to a minimum of 13 and a maximum of 242 at the ICTR, and a much smaller range at the ICC (55–77). In terms of average witness numbers per trial both the ICC and the ICTR rely on considerably fewer witnesses compared to the ICTY (ICC M=64, ICTR M=66).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of viva voce witnesses called, 1997–2017

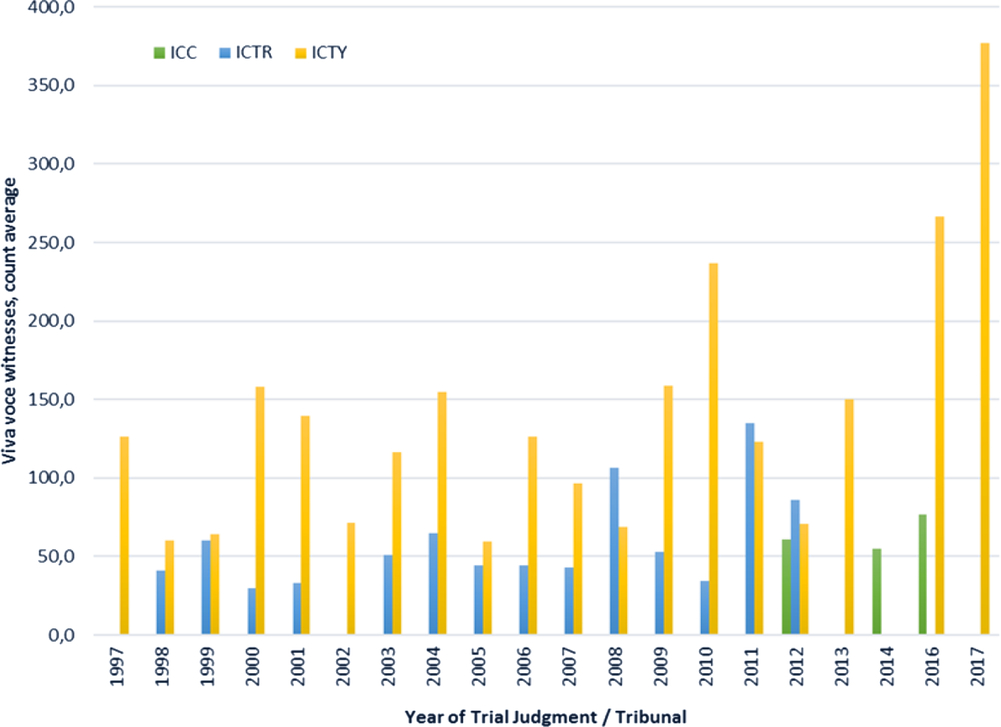

In order to illustrate how the witness numbers varied over time, Figure 1 above depicts the average number of viva voce witnesses per case per year at each of the three major ICCTs during the period of 1997–2017.

Figure 1. Oral testimony in numbers: trends at the ICTY, the ICTR, and the ICC.

2.1 Observation #1: High variability in numbers of trial witnesses over time

The quantity of live witness testimony referred to in the trial judgments did not increase or decrease steadily over the years. As Figure 1 clearly demonstrates, the numbers were highly variable across cases, time periods, and institutions in charge of the adjudication.

The fluctuations in witness numbers over time are, in part, reflections of the historical period of tribunals’ work, political context and changes in the institutional practices (e.g., appointment of new prosecutors, or amendments to the rules). For example, some of the lowest numbers of witnesses were called during the first phase of the ICTY and the ICTR (1997–2003). During this time the courts faced a number of issues, inter alia, the inability of finding and securing witnesses, obtaining state co-operation, or the inexperience and lack of established institutional practices.Footnote 29 It is of note that when the ICTY came into operation the war was still ongoing in the territories under its investigation, hampering the ability to contact witnesses.Footnote 30 In addition, a number of states on which the ICTY depended for securing the evidence were less than co-operative, especially until the 2000s.Footnote 31 While the initial years of the Rwandan tribunal appear to have been less riddled with troubles, in 2002 the ICTR President reported serious delays due to lack of co-operation by the Rwandan government leading to non-appearance of witnesses, as one of the major issues facing the institution.Footnote 32 As a case in point, in Niyitegeka, out of 16 prosecution witnesses scheduled to testify only two appeared. Similarly, in Butare in the first three phases of the trial only four out of 11 scheduled witnesses were present.Footnote 33

While the contextual factors have undoubtedly been influential in the strategies of case selection and prosecution, including how many viva voce witnesses the parties were willing and able to call, it is unlikely that they explain the whole picture. For example, we observe substantial variability in the average numbers of witnesses called in consecutive years: the ICTR called 35 witnesses on average in 2010, and 135 in 2011. The ICTY average number of witnesses between 2008 and 2009 ranged from 69 to 159. Taking into consideration the rather slow pace of change in institutional practices of large-scale organizations, the observed differences in witness numbers in consecutive years is likely to also reflect the variability in case characteristics and their complexity.

2.2 Observation #2: The ICC and the ICTR call, on average, fewer viva voce witnesses than the ICTY

Another observation is the considerably higher numbers of live witnesses at trial at the ICTY in comparison to the ICTR and the ICC. The varying institutional mandates and practices among the three ICCTs can provide some explanation for this. The geographical and temporal scope of the ICTY’s tasks has been by far the broadest: its judicial record covers five modern day states: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, Kosovo, and the Republic of Macedonia.Footnote 34 In terms of population, the ICTY had jurisdiction over the crimes committed by and against over 23 million individuals representing at least ten ethnic groups, in comparison to a little over 7 million mainly Hutu, Tutsi, or Twa people in Rwanda.Footnote 35 In contrast to a civil war with two main belligerents in Rwanda, which culminated in the genocide organized by the Interim Government against mainly the Tutsi minority, the conflict in the Former Yugoslavia encompassed a large number of state and non-state actors with shifting allegiances and goals. Additionally, while the ICTY attempted to investigate and prosecute a number of parties to the conflict, the ICTR only prosecuted the belligerents of one side, i.e., crimes committed by and on behalf of the Interim Government; no alleged crimes by its adversary at the time, i.e., the Rwandan Patriotic Front, were charged. In addition, the temporal jurisdiction of the ICTY was open-ended and covered crimes committed since 1991. The ICC, while potentially having jurisdiction over the whole world, in reality has only prosecuted accused for offences committed in a single country.Footnote 36 A broader jurisdictional scope arguably can complicate the investigations and prosecutions by requiring more evidence and access to multiple crime sites. It also commonly translates into a larger pool of potential witnesses. Within the institutions the broader geographical and temporal scope could also lead to more variation among the cases, due to the diversity of their character: Indeed, we find more internal variation in trial witness numbers within the ICTY cases than those at the ICTR or the ICC.Footnote 37

As indicated above, both the ICTY and the ICTR faced difficulties in obtaining and securing live witness testimony. However, this issue appears to have been more pronounced at the ICTR, due to several specific concerns. First, researchers note the inabilities or unwillingness of the Rwandan government and judicial system to provide protection to (defence) witnesses, and as such, assist the ICTR.Footnote 38 Even further, allegations abound that the individuals acting on behalf of the Rwandan government had tried to pressure witnesses into not testifying. Relatedly, the potential witnesses reportedly were deterred from testifying in defence of genocide suspects so as not to be accused of harbouring ‘Genocidal Ideology’ themselves.Footnote 39 The threats were not limited to the defence witnesses, as documented by human rights organizations,Footnote 40 and significant allegations of witness intimidation were present at almost every ICTR trial.Footnote 41 While the ICTY witnesses undoubtedly were threatened, intimidated, and otherwise obstructed from providing their testimony, especially in the cases related to Kosovo or Macedonia,Footnote 42 their availability outside of the countries of origin, the relative ease of travel within Europe, and increasingly over time stronger state co-operation lessened such constraints in comparison to the ICTR.

Likewise, the procedural frameworks and the degree of judicial intervention differ at the three institutions. Whereas the ICTR emphasized the importance of judicial control over, e.g., how many witnesses the parties are allowed to call, since early on in the trials,Footnote 43 the ICTY only allowed for such judicial involvement with the amendment of the rules in 2001.Footnote 44 However, the early adoption did not necessarily translate into comparatively more judicial control. Further amendments to the ICTY rules resulted in more intervention by the Chambers over time.Footnote 45 Moreover, the ICTY appears more open to the practice of admitting written depositions instead of live witness testimony, being the first to adopt various rules facilitating such admission.Footnote 46 Regarding the ICC, one should not ignore that it has benefitted from the experience of the ICTY and the ICTR, which informed its foundational documents. The Court began its operations with the rules allowing for the admission of written statements and other testimony in lieu of appearing in court already in place.Footnote 47 Whatever the intended and actual effects of the specific institutional contexts and practices, the fact that the ICC and the ICTR have called, on average, considerably fewer witnesses per trial than the ICTY can also relate to different characteristics of cases at hand and their complexity, as we explore below.

2.3 Observation #3: The number of viva voce witnesses increased over time

A final observation from Figure 1 is that, despite the fluctuations, there seems to have been an overall increasing trend in viva voce witness numbers, in particular in the later trial years at each of the Tribunals.

It seems that despite intense efforts to shorten the trials, the parties called increasingly more witnesses over time, especially at the ICTY. The various rules implemented in pursuit of efficiency (Section 1) thus appear to have been either not applied or ineffective. Indeed, a previous empirical study found that the introduced procedural changes at the ICTY were counter-effective and resulted in lengthier trials, and the statements admitted in lieu of oral testimony were generally used on top of, and not as a replacement for, viva voce witnesses.Footnote 48 Similarly, McDermott concludes that the rules allowing for the admission of witness statements in place of (part of) live testimony were largely not utilized by the parties at the ICTR.Footnote 49 However, it is also plausible that the cases adjudicated in the initial phases of the tribunals’ lifetimes were different, less complex than the later ones, which indeed included more high-ranking accused, charged with longer and broader campaigns of violence, simultaneously characterized as all three legal categories of international crimes.

3. Explaining variation: Case complexity and efficiency factors

Having observed the fluctuations in the number of witnesses called per trial over time and across ICCTs, we turn to case-related factors to explore whether they are indicative of how many witnesses appear to testify per case. We hypothesize that the variability in numbers of witnesses is likely related to the complexity of the cases at trial. Case complexity and scope is a rather commonly cited justification for lengthy proceedings at the ICCTs,Footnote 50 and is allegedly one of the ‘central challenges facing the judges’.Footnote 51 However, conceptually it remains a rather vague notion in relation to (international) justice: it is not clear how to operationalize case complexity, and little empirical research has been carried out with the aim of examining it. The notable exception, Ford,Footnote 52 distinguishes three types of complexity: factual, participant, and legal. He argues that factual complexity depends on the issues that need to be (dis)proven at trial, and as such increases if, inter alia, the crimes are committed by groups of people working together, crimes take place across multiple locations, and/or over long time periods. The second, participant complexity, increases with the number of defendants (single-accused trial thus being less complex than multiple-accused trial) and their authority levels. Lastly, legal complexity depends on whether the law is determinate and certain (i.e., the legal precedent is consistent and clear), whether it is technical in nature, and how dense it is (i.e., having many elements or requirements). The importance of these three types of complexity factors has also been confirmed in practice, by the judges of the ICTR as well as the legal aid section of the ICTY.Footnote 53

We focus on the aspects of case complexity present in the indictments issued by the prosecutorsFootnote 54 by which the accused are charged, and which, in essence, delineate the focus and scope of trials. First, we include rather straightforward factors related to the charges, such as the number of counts, the length of criminal activity charged, or the number of accused. In simple terms, all other things being equal, proving the guilt of one accused on one count spanning one day would require less evidence than in the case of multiple accused committing multiple offences over a longer time span. It is also reasonable to expect that each defendant would call his/her own witnesses, increasing the amount of live testimony.

A less clear-cut, though highly important, case complexity factor is the hierarchical rank of the accused, i.e., his/her actual position within the political or military structures. International crimes are typically a result of large scale, collective and organized action. Thus, the defendants in international courtrooms, whether associated with the military or the political apparatus, represent various levels of organizational leadership. The idea that the so-called leadership cases are more complex to investigate and prosecute than those concerning foot soldiers appears to be generally accepted.Footnote 55 By including the rank/position of the defendant, we investigate whether it translates into more witnesses called to the stand. Similar to other empirical studies of ICCTs,Footnote 56 we classified the defendants’ positions within the overall state or non-state organizational hierarchy into four categories: high, middle-high, middle, and low. The categories represent the differing degrees of authority and autonomy of the accused. The lowest category contains individuals ‘on the ground’ with little to no authority to give orders or otherwise influence the situation (e.g., soldiers, duty officers, guards, police officers). A step higher, the middle-ranking category encompasses defendants with a broader de jure or de facto authority, who have the power to command or influence a certain group of people, such as lieutenants, captains, sergeants in the military, militia/paramilitary commanders, or civil servants such as leaders of regions/municipalities (bourgmestres/sous-bourgmestres at the ICTR), priests, and media influencers. The third, middle-high, rank is made up of political party leaders, high-office holders in the ministries, and high-ranking military commanders (ranging from brigadier general to commanders of tactical groups). The high echelon of leadership in our dataset are the presidents, prime ministers, ministers, chiefs of staff of the army, chiefs of national police or gendarmerie, and military commanders in charge of armies, corps, and divisions.

Further, defendants at the ICCTs are linked to individual crimes by applying different modes of liability. A mode of liability is a legal construct that reflects the manner in which the accused participated in or contributed to the crimes. In broad terms, the ICCTs statutes differentiate between individual and superior liability.Footnote 57 Superior liability is a liability by omission for the crimes of others, deriving from a position of authority and superior–subordinate relationship. Consequently, it needs both the proof of the crimes that the accused did not punish or prevent, his/her knowledge of the crimes taking place, and proof of the accused having been in position of effective control of the perpetrators. Arguably, due to these characteristics, proving superior responsibility may necessitate more facts to be proven at trial, and thus increase the amount of evidence, including witnesses.Footnote 58

Next, the ICCTs have jurisdiction over the crimes of genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes. While their statutes do not distinguish between the crimes in terms of their seriousness, arguments have been advanced that the crime of genocide is the most grave and complex.Footnote 59 Genocide has particular legal requirements that have proven difficult to prosecute, inter alia the requirement of specific intent to destroy a protected group and the narrowly defined protected groups.Footnote 60 These legal requirements might result in the need for more evidence. A number of authors argue that crimes against humanity are at least more complex than war crimesFootnote 61 since they require proof of (i) widespread and systematic attack against a civilian population, and (ii) the perpetrator’s knowledge of his contribution to such an attack. Footnote 62 Furthermore, crimes against humanity stem from customary international law, which is arguably more ambiguous than the treaty-based origins of genocide or war crimes. Theoretically, legal uncertainty allows for multiple interpretations of what individual elements of a crime mean and what is necessary to prove them on trial. This legal ambiguity opens up more avenues for the parties to argue their case, supposedly increasing the total amount of evidence at trial. In turn, war crimes, with their mainly treaty-based character and the armed conflict nexus as the main chapeau element are arguably the least complex category of international crimes. To see whether these legal differences are related to witness numbers, we included all the crime categories and combinations thereof.

Finally, we included two variables representing measures adopted by the tribunals to decrease the amount of live witness testimony: the number of witnesses who testified not viva voce and the number of facts accepted by judicial notice. Since the amendments of the rules, a number of witnesses were allowed to testify fully or partially by means of a signed deposition/statement. As these rules were advanced with a view to speeding up the proceedings by reducing the number of witnesses at trial,Footnote 63 we would expect to see a reduction in the amount of live witness testimony depending on the number of non-oral testimonies accepted by the judges. In a similar vein, decreasing the number of facts that have to be argued at trial is presumed to ‘achieve judicial economy’ by reducing the evidentiary load of the case.Footnote 64 Therefore, we include the number of facts the judges have taken judicial notice of to see whether they relate to changes in witness numbers. The overview of the data we collected is provided in the Annex (Table 1).

4. Results: Witness numbers in relation to complexity and efficiency

The relationships between the case-related factors and the numbers of viva voce witnesses were explored using bivariate correlation tests.Footnote 65 Such tests allow us to measure the strength of association between two variables, and its direction (positive/negative). We examined the relationships between witness numbers and complexity and efficiency factors for the ICTR and the ICTY separately as the two datasets were highly divergent,Footnote 66 and excluded the ICC from statistical tests due to small sample size (ICC data is included in a descriptive manner, see Figures 2, 3, 4). Table 2 in the Annex presents complete outcomes of the calculations.

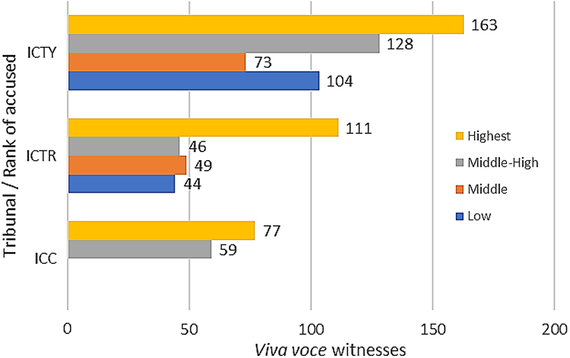

Figure 2. Average witnesses per case dependent on the highest ranking accused in a case.

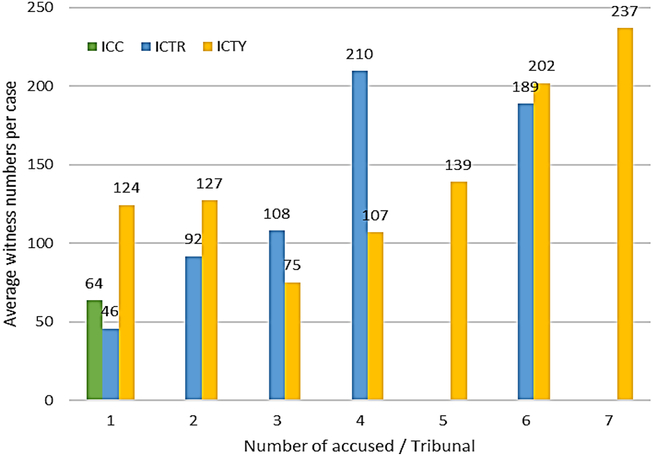

Figure 3. Average viva voce witnesses per case by the number of accused.

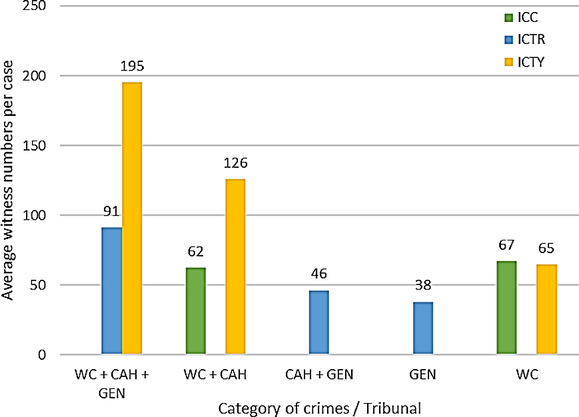

Figure 4. Average viva voce witness numbers in relation to category of crimes charged, per tribunal.

4.1 Participant complexity: Number of accused and their authority levels

We find clear differences in the relationships between participant complexity factors and trial witness numbers at the ICTY and the ICTR. While in absolute numbers, it appears that the highest rank of the accused (see Figure 2) is more reflective of the number of witnesses called during trial than the number of accused (see Figure 3), in fact these relationships are more complex.

First, at the ICTY, although the largest absolute amount of witnesses was called when the highest number of high-ranking defendants were standing trial together (see Figures 2–3), these correlations are not statistically significant. Hence, these factors, in isolation, do not explain the variation in witnesses at the ICTY well. Meanwhile at the ICTR, the findings appear to align with case-complexity assumptions: viva voce witness numbers are significantly higher in cases with more accused, and when they are high-ranking.Footnote 67 In fact, the difference between the numbers of witnesses called when at least one of the accused is high-ranking and all the other authority categories here is starker than at the ICTY or the ICC (see Figure 2). However, once we take into account the potential overlap between the rank and the number of accused within a single case, we discover that at the ICTR the effect of the rank of a defendant is lost when controlling for how many defendants stand trial together (we find no such effect at the ICTY).Footnote 68 Thus, for the ICTR it seems to be mainly the number of accused and not their rank in the hierarchy that is associated with higher numbers of witnesses, as further illustrated in Figure 3.

These outcomes may reflect the different approaches of the two courts in relation to single- and multiple-defendant cases. While the ICTY had more multiple-accused trials than the ICTR (ICTY n=21, ICTR n=9), high or middle-high ranking defendants at the Rwandan tribunal were more likely to be tried together, which explains the results.Footnote 69 The lack of statistically significant relationships between witness numbers and factors related to defendant characteristics at the ICTY might also mean that other aspects of the cases (legal or factual complexity) better explain this internal variation, as explored below.

4.2 Complexity of the charges/case: Number of counts, period of charges, and category of crimes

The analysis also revealed differences between the ICTY and the ICTR regarding the complexity of charges factors. Here again, the relationships uncovered at the ICTR confirm our expectations: more counts, covering a broader temporal scope relate to more witnesses called at trial, which does not seem to be the case at the ICTY.Footnote 70 These differences between the tribunals can be partially explained by the divergences in their charging patterns. Since the ICTR was concerned with an event of a limited, pre-defined time-span,Footnote 71 the range and variability of the period charged is considerably smaller than that of the ICTY. Footnote 72 Similarly, the number of counts charged per case at the ICTR is narrower and less fluctuating than at the ICTY.Footnote 73 These widely spread ICTY charging practices result in highly irregular data (indicated by large standard deviationsFootnote 74) and a considerable amount of outliers. Calculations performed on such data are less reliable and the data characteristics might be one of the reasons for the counter-intuitive results. Besides this, it may also be the case that even though the ICTY charged, on average, more counts per case, they related to the same incidents or were related to facts already adjudicated in prior cases, and thus did not require exponentially more witnesses.

Next, we found the correlations between the witness numbers and the categories of crimes charged to be in accordance with the assumptions of legal complexity, which increases when more complex or broader legal concepts need to be adjudicated.Footnote 75 At both tribunals, cases including charges of all categories of crimes (genocide (GEN), war crimes (WC), and crimes against humanity (CAH)) has moderate, positive correlations with witness numbers. These are also the cases where the largest numbers of witnesses are called on average (see Figure 4).

In addition, we found a moderate negative relationship between war crimes-only charges and the number of witnesses at the ICTY. In fact, at both institutions the lowest numbers of witnesses on average were called in single-category cases: Genocide at the ICTR (M=38) and war crimes at the ICTY (M=65).Footnote 76 This partially supports our hypotheses, as fewer categories charged indicate lower legal complexity. However, this result goes against the assumption that genocide, as the legally most complex category would require more evidence, including witnesses. Further understanding of these findings necessitates reflection on the charging patterns. At the ICTY, genocide was charged only in combination with the two other categories of international crimes, so we cannot separate the relationship of genocide charges and the numbers of witnesses. At the ICTR, all defendants were charged with genocide, in the majority of cases in combination with crimes against humanity and/or war crimes. Since there were no cases not including genocide charges, it is difficult to draw any meaningful comparisons among the categories. In addition, it is also significant that in 2006 the ICTR judges accepted the occurrence of genocide as a fact of common knowledge, relieving the prosecution in this and subsequent cases of the burden to produce evidence on it.Footnote 77 At the ICC, no genocide charges have been issued in any of the cases that have yet made it to trial. Any meaningful comparisons in this respect, thus, cannot be made.

4.3 Efficiency factors: Fruitful efforts?

The two factors included in our analyses to see whether the initiatives meant to reduce the numbers of witnesses called at trial were successful demonstrate no evidence of any intended effects. In fact, at the ICTR, the number of witnesses whose statements were admitted in lieu of oral testimony was positively correlated with the number of viva voce witnesses,Footnote 78 indicating that the number of viva voce witnesses increases with more prior recorded testimony admitted in a case. Further, we found no statistically significant relationship between prior recorded testimony and the number of witnesses called to testify at the ICTY. Notably, the two institutions relied upon the new rules in widely divergent ways. In the vast majority of the ICTR cases no witnesses testified via prior deposition (only 13.64% of cases had more than one witness testimony admitted in writing; 83.21% of all the not viva voce witness testimony was admitted in a single case, Karemera et al.). Thus, the numerical analyses are based on a limited sample. This in itself is indicative of the meagre impact these procedural changes had on the evidential record of the ICTR: Even the cases with very high viva voce witness numbers had little of this testimony replaced or supplemented with written depositions, the pattern remaining consistent over time. In comparison, the ICTY made much broader use of the rules allowing witnesses to testify in writing: The majority of the cases had at least some written testimony admitted (70.45% of cases had more than one such witness). Supplementary analyses revealed that the factor most indicative of higher not viva voce testimony at the ICTY is the date of the judgment.Footnote 79 Cumulatively, these observations reveal the, over time, increasing willingness of the parties and judges to utilize untested witness testimony at the ICTY (with no observed reduction in witnesses), and the relative conservatism of their counterparts at the ICTR (likewise with no observed reduction). While the ICTR demonstrates the most cautious approach, it is no different from all the trial judgments passed down by the ICC to date.Footnote 80 Little to no use of Rule 68(2) or 68(3) was made in these cases, though the situation is currently undergoing change. In the trials of Dominic Ongwen, Bosco Ntaganda, and Laurent Gbagbo and Charles Blé Goudé, both the defence and the prosecution have already introduced dozens of witness statements in lieu of their testimony at trial,Footnote 81 with the judges demonstrating an unprecedented willingness to accommodate such requests.Footnote 82 Thus, the ICC appears to have recognized the need for expediency and the potential utility of avoiding large numbers of trial witnesses in achieving speedier proceedings. However, looking at absolute numbers, we see that these latter (ongoing) cases have utilized much higher numbers of oral witness testimony at trial. While in the four non-guilty plea cases where trial judgments have already been rendered the OTP called 31 witnesses on average, in the later cases, where more of the expediting measures have been adopted, they have called more than double, 74 witnesses on average. In terms of the defence, we only have provisional data on the ongoing cases, but the numbers are also higher than those in the initial cases (53 on average).

Regarding the other efficiency measure, judicial notice of facts, we observed no significant relationship with witness numbers at the ICTR, and a positive correlation at the ICTY. Overall, the ICTR did not rely on the judicial notice doctrine heavily; only 11 per cent of the trial judgments mentioned more than one adjudicated fact.Footnote 83 The maximum number of facts the ICTR judges took judicial notice of within a case was 147. Compare that with the ICTY, where adjudicated facts range from zero to 2,379, and more than a third of the trial judgments refer to at least 40 of them. Still, the use of a doctrine did not result in less testimonial evidence presented at trial. Similar to the observations regarding admission of written testimony, our findings are in line with previous empirical studies, concluding that the procedural changes did not have their intended effects.Footnote 84

The reasons for such outcomes can vary, one among them being that the cases where more witness testimony was admitted in writing were also systematically more complex, requiring more testimony overall. In that case, had the new rules not been in place, the parties might have called even higher numbers of witnesses to the stand. Along these lines, supplementary analyses revealed that more written witness testimony was indeed admitted in cases with higher-ranking accused and more categories of crimes charged at both institutions.Footnote 85 However, based on the calculations and the descriptive analysis of the ICC, it still seems evident that the ability to admit witness testimony in ways other than oral did not directly lead to significant reductions in trial witnesses.

5. Discussion and conclusions

This article starts with the often-employed explanation for why international criminal trials are such lengthy pursuits, requiring hundreds of individuals to put their daily lives aside and come testify; ‘the case complexity and scope’. The phrase is not only over-used but also largely based on individual experiences or observational, anecdotal knowledge. Hence, this study attempts to empirically explore the existing assumptions regarding the effects of case complexity on a salient ‘result’; the number of viva voce witnesses at trial. Our analyses of newly collected data from the ICTY, the ICTR, and the ICC indicate that legal, participant, and factual complexity aspects of the ICCT cases are related to the changes in the numbers of trial witnesses. However, the direction of the relationship is often counterintuitive. Our results mirror the complex landscapes of international criminal prosecutions, and the range of the cases decided at the three judicial contexts. We observe significant differences in the amount of trial witnesses over time, across institutions, and in between cases at the same institutions. In this, some patterns emerge.

First, and importantly, we see more variance between institutions than between cases within an institution. While it is correct that the ICTY and the ICTR had a fair share of similarities, not to mention the processes of their creation, the actors involved and the conflicts preceding their inception had little in common, as described in Section 2. Accordingly, the considerably lower number of witnesses called at the ICTR is possibly a product of its institutional practices and context, more limited charges with smaller geographical and temporal scope combined with the persistent difficulties in securing live witness testimony, reducing the need for and the ability to call as many witnesses as the ICTY. Our statistical analyses, showing significant differences in the numbers of trial witnesses at the ICTY and the ICTR, and their contrasting relationships with the complexity and efficiency related factors also confirm the choice of treating the tribunals as unique judicial contexts with distinctive political, historical, and operational environments. This should inform future researchers of the dangers in studying the ‘ICCTs’ as a singular phenomenon.

Second, according to our expectations, certain case complexity characteristics are associated with the numbers of trial witnesses. At the ICTR, we found positive correlations with high authority levels of a defendant, more counts, longer periods of charges, and more categories of crimes charged. Conversely, at the ICTY we observed a number of unanticipated outcomes, none of them in line with case complexity hypotheses. While we suppose some of these results are due to the highly skewed nature of the data (there were strong, systematic differences between several major cases, and the rest), the data is also a reflection of the higher variety of the trials held at the ICTY. As discussed above, the Yugoslavia tribunal had a much broader temporal and geographical mandate than that of the ICTR and the characteristics of the ICTY cases were much more diverse. Moreover, the high variability between the cases at the ICTY highlights the possibility that, even within the same institutional context, individual cases, especially if they concern crimes committed in different states or by different actors, may be better understood as separate ‘universes’. The interplay of their unique contexts and characteristics necessitates and allows for considerably different investigative and prosecutorial strategies, producing largely variable witness numbers contrary to any assumptions, which is especially important to keep in mind if attempting any analysis of the ICC as a singular unit.

Another noteworthy finding is the apparent ineffectiveness of the tribunals in reducing the number of trial witnesses. Notwithstanding the increasing focus and rules promoting efficiency, it seems that over time the parties kept on calling more witnesses to the stand. We entertain a number of potential explanations: the parties could have been changing their behaviour to neutralize the impact of the new rules, for example by introducing supplementary witnesses via written testimony, and calling the same number of witnesses at trial. Additionally, the rules allowing the admission of written statements and transcripts in lieu of oral testimony were rather narrow and applied mostly to evidence going to ‘proof of a matter other than the acts and conduct of the accused’.Footnote 86 Accordingly, the parties could only dispense of the viva voce testimony from the non-core witnesses in the case. Finally, the judges, deliberately or not, could have made limited use of the new rules and procedures, especially in relation to oral witness testimony. The two measures adopted to decrease the amount of live testimony that we included in bivariate tests show no link with its reduction. Although the ICC was not assessed statistically, the parties there have also called increasingly more witnesses during the more recent, ongoing trials, where a number of measures expediting the proceedings by admission of pre-recorded witness testimony were used. The finding that the admission of not viva voce witness testimony did not seem to have reduced the amount of witnesses at trial may be worrying from the efficiency point of view. On the other hand, it can also be reflective of the caution exercised by the judges in balancing their obligations towards the accused as well as the fulfilment of their fact-finding role in increasingly more complex cases.

This article is part of emerging empirical legal scholarship of international criminal law, providing data and evidence base for statements on procedures and practices in the international courtrooms. Its contribution lies not only in its findings but also in the example of how the treasure trove of the archives of the ICCTs can be exploited for the use of scientific inquiry. At the same time, this type of empirical study of international criminal law faces challenges. Even though the tribunals have been active for over 20 years, only slightly more than 100 trial judgments have been issued. At the same time, the convoluted character of international crimes cases calls for complex multivariate models and explanations. However, given the small sample size, possibilities for statistical analyses are inevitably limited. Widely different cases, including extremely large ones against former heads of state as well as very small ones against foot soldiers, are bound to lead to outliers and ensuing distortions in any modelling. We hope to have sufficiently addressed this issue by combining a number of techniques to understand the same data. Further, the information available to the researchers fundamentally depends on the transparency of the tribunals, the completeness of the repositories, and the accuracy of their cataloguing. Finally, even if the information gathered in secondary sources is as complete as possible, the internal operations and decision-making of the courts, whether international or not, is a highly sensitive area subject to substantial privacy considerations. While these concerns are justified, it also means that any explanations gleaned from public sources will only be able to paint the ‘outside picture’.

Our article has demonstrated that, despite these limitations and challenges, there are multiple possibilities to use empirical social scientific methods to explore functioning of the ICCTs. The scholarship of international criminal justice is in need of empirically grounded analysis and more evidence-based discussions to evaluate and draw lessons from the past and move forward.Footnote 87 Remarkably little has been subjected to empirical examination, and we hope that this study is another step towards a better understanding of functioning of the three key institutions dispensing international criminal justice.

Annex

Table 1. Measurement strategies and descriptive statistics

Table 2. Results of bivariate correlation tests