1. The Concept of National Security

There is an inherent indeterminacy in the term ‘national security’, which is essentially a function of the endowments and the risk aversion of the agents involved. A threat by St. Kitts and Nevis could look credible to Grenada but not to the United States (US). Similarly, Poland, a country that has seen its frontiers repeatedly change over time, might legitimately be more cautious when facing a threat than, say, a country such as St. Kitts and Nevis, which has practically never participated in (similar) warfare.

And here is the conundrum: to better understand to what extent specific means best serve the end (i.e., national security), we need to be clearer regarding the ambit of the term ‘national security’. Here is an illustration of why. Assume Patria considers having a certain minimal level of domestic production of semiconductors essential for safeguarding its cybersecurity. Alternatively, Patria could also take the more extreme view that complete self-sufficiency in this market is a prerequisite for its national security, so it does not wish to ever rely on foreign suppliers. Patria could achieve either of these goals by subsidizing the production of semiconductors or by implementing restrictive trade policies that limit imports. Does it matter which path it chooses? Similarly, what if Patria wants to promote its national security by reducing the income that Xantia, its archenemy, has at its disposal to finance its war machine? Patria domestic subsidies would be of limited help in this scenario, and Patria could conceivably be better served by restricting imports from Xantia. A trade embargo might do the trick, depending on the importance of Patria for Xantia's exports (and the ensuing switching costs for Xantian exporters).

All this is to state that the amorphous concept of ‘national security’ needs dis-aggregation if we want to assess the suitability of specific means to achieve the ultimate end. We argue that lumping various disparate objectives under the broad umbrella of national security hinders the identification of optimal policies. Instead, we examine how scrutiny of excised instruments offers a better starting point towards diagnosing complex security policy.

2. Security in the GATT-World

Article XXI of GATT acknowledges the right of its members to defend their essential security. Economic literature has privileged the term ‘national security’ when evaluating the intersection of power politics and states' domestic policy goals Wolfers (Reference Wolfers1951). However, the GATT exceptions rely on the term ‘essential security’, implying the elevation of security to a matter of international relations. Further, the absence of emphasis on ‘national’ reinforces to WTO members that justifying action inconsistent with international commitments does not strictly rest on a domestic determination. GATT Article XXI sets out how WTO members may deviate from GATT commitments:Footnote 1

• WTO members may refuse to disclose any information that goes against its security interests (Article XXI(a));

• WTO members may take necessary (undefined) measures to protect their essential security interests in specific circumstances (Article XXI(b)); and, finally,

• Nothing in the GATT can stop a WTO member from observing its obligations under the United Nations Charter (Article XXI(c)).

Over the years, while members have raised concerns about the relationship between information disclosure and assessing a member's invocation of Article XXI, to date no panel findings have explicitly defined this relationship. Rather, WTO members have only invoked GATT Article XXI to justify security measures as necessary in an emergency in international relations, which is also true of the cases we discuss in this paper.Footnote 2

2.1 The Text of Article XXI: When but Not How

The body of Article XXI does not prejudge the instruments that a GATT member can employ to safeguard its security interests. Owing to the complex relationship between what a member chooses to disclose and the protection of essential security interests, the question of ‘when’ an action occurs is central to a panel's objective assessment of GATT Article XXI(b). Sub-paragraph (b)(iii) of Article XXI more obviously considers ‘when’ as the text demands action in times of specific events, namely war or an international relations emergency. However, the ‘when’ question remains applicable for sub-paragraphs (b)(i) and (ii), respectively, as the ‘when’ must be a government taking necessary trade action for protecting essential security interests relating to ‘fissionable materials’ or for ‘the purpose of supplying a military establishment’.

Notwithstanding a narrow corridor concerning ‘when’ action to protect essential security can lawfully occur, the GATT remains silent regarding the variety of means available to reach the ends sought (protection of essential security interests). The text of GATT Article XXI states, ‘Nothing in this Agreement’ prevents a member from acting. The term ‘nothing’ confirms that members may choose from a wide array of instruments: increased tariffs, banned imports/exports from a specific source, subsidized production, or exclusion of a particular source from privileges under behind-the-border policies available to its production. Under what circumstances is each of these instruments optimal? We turn to this vital question next.

3. Optimal Economic Policies for National Security

While the maintenance of national security certainly has some economic dimensions, at its heart, it is fundamentally not an economic issue. An example helps. Suppose a country has market power in the world market for a product, in the sense that it can improve its terms of trade (i.e., lower the world price of its imports) by imposing an import tariff on it. As is well known, a country's optimal tariff balances the deadweight losses suffered by local consumers against the terms of trade improvement generated by the reduction in the net price collected by foreign sellers. Manipulating one's terms of trade via a cleverly designed import tariff is an example of a policy intervention based on purely economic considerations. Similarly, Helpman (Reference Helpman and Stern1988) has advanced the argument that a decision to preserve a monopoly status for a producer, say of arms, could be justified through export restrictions in the name of national security.Footnote 3

Now consider a situation where a specific intermediate input is critical for maintaining a country's defence infrastructure and industry. If so, the country may wish to avoid becoming overly reliant on imports since its ability to defend itself could be compromised if it can no longer easily secure the product from foreign sources, either due to economic changes in the world market, or because of the outbreak of an international conflict that impedes trade. Given these concerns, the country might justifiably pursue a non-economic objective that prioritizes domestic production of the good. Alternatively, it might even wish to be fully self-sufficient in the production of such a good and implement policies that help achieve that objective.

3.1 Using Economic Policies to Pursue Non-Economic Objectives

The concept of a non-economic objective was defined and developed in a series of papers by the great Harry Johnson who noted that, when pursuing such an objective, trade protection seeks to maintain a structure and composition of output for its own sake, as opposed to maximizing national real income or welfare.Footnote 4 Indeed, one key aspect of using trade policy measures to pursue non-economic objectives is that doing so usually lowers real income of the imposing country. For example, a central proposition of the economic theory of trade policy is that the optimal tariff for a ‘small country’ (i.e., one that has no ability to influence its terms of trade) is zero. In other words, a small country should practice free trade if it seeks to maximize national welfare. But small countries can have national security concerns as do large ones. If anything, their concerns could be even more pronounced, and if they use import tariffs to encourage local production of certain goods, they would be deliberately choosing a trade policy that is sub-optimal from a strictly economic perspective, but potentially justifiable because of national security concerns. The presence of such a trade-off is inherent to the pursuit of any non-economic objective, such as national security.

The formal literature in economics on the pursuit of non-economic objectives has provided several useful insights regarding the best means for pursuing such objectives and clarified that while all roads might lead to Rome, some of them might do so faster or at a lower social cost. In a classic paper, Bhagwati and Srinivasan (Reference Bhagwati and Srinivasan1969) drew an important distinction between a scenario where a country's primary policy objective is to simply encourage local production of a good versus another where the goal is to increase self-sufficiency in the sense of meeting more of its local demand by local supply than what occurs under free trade.Footnote 5 It turns out that the subtle distinction between these two objectives matters a great deal for the optimal policy prescription.

3.2 Encouraging Domestic Production

At the most general level, a country might wish to encourage domestic production of a good if its social marginal cost of production is lower than the private cost incurred by its producers. Public goods are often characterized by this discrepancy between social and private costs or between social and private benefits. For example, consider the production of weapons that help bolster national defence. By discouraging attacks from potential enemies, a stronger national defence may foster investments and growth in the broader economy that benefit private citizens as well as other industries, but such benefits would typically not be captured by the defence industry, at least not fully. In effect, the industry's perceived private cost of production would be higher than the true social cost, the difference between the two being the external benefits generated by its output for the rest of the economy. If left totally to its own devices, the industry's output would fall short of the socially optimal level since its profit maximization calculus would fail to account for the external benefits of its production. In such a situation, there is a case for policy intervention that seeks to encourage local production of the weapons in question. The question is how best to achieve this outcome. A rich literature in economics has addressed this question and argued that production subsidies are superior to import tariffs for incentivizing the local industry to produce the socially optimal level of output. Figure 1 illustrates the basic argument.

Figure 1. Encouraging domestic production: tariff versus subsidy

In Figure 1, the supply curve for the local industry (which is its private marginal cost curve) lies above the social marginal cost of local production, since there is a social benefit to local production that is not captured by the local industry. Indeed, the vertical distance between these cost curves denoted by parameter β measures the amount by which the industry's private cost of production exceeds the social cost. Under the free trade price pF, local production is xF while consumption equals dF, so that mF = dF–xF measures imports. However, the socially optimal level of local production xW is pinned down by the intersection of the free trade price pF and the social cost of local production. As is clear from Figure 1, xW > xF. This is not a surprise: since the private cost of the industry exceeds the true social cost of producing the good, the industry's output is sub-optimally low. This discrepancy calls for policy intervention aimed at increasing local production of the good. But what type of policy intervention is optimal?

Consider first a production subsidy s set at a level that helps align the private costs of production with social costs, i.e., s = β. In Figure 1, this subsidy policy costs the government – (A + B) in terms of subsidy payments and generates additional surplus of A for local producers who receive an effective price of pF + s. Since local consumers continue to consume dF at the free trade price pF, they are completely unaffected by the subsidy. The total external benefits generated by the subsidy are captured by the area lying between the social and private cost curves and the expansion in output caused by the subsidy from xF to xW, i.e., areas B and E. Taking account of all parties, we calculate that the net effect of the subsidy s = β on local welfare as ΔW S = –(A + B) + (A + B + E), i.e., the subsidy increases local welfare by the amount E.

Now suppose the local government were to impose an import tariff t that exactly equals the differential between social and private cost of local production, i.e., t = β. Like the subsidy, the tariff too induces the socially optimal level of local production xW but, unlike the subsidy, it simultaneously reduces imports from the socially optimal level dF to dT, thereby generating a loss in consumer surplus of area D. Thus, for the policy objective at hand, the tariff proves to be an inferior policy tool relative to the subsidy since it generates a lower net gain of ΔWT = E–D. Note also that it is possible that E < D, i.e., not only is the tariff a worse instrument than a subsidy for increasing local production, it also does not necessarily raise local welfare relative to non-intervention.

While the above analysis justifies policy intervention due to a positive externality associated with production, the superiority of the production subsidy over the tariff for encouraging local production does not require such an externality to necessarily exist (i.e., hold even when β = 0). Indeed, even if the government seeks to encourage local production for any other reason, including pure protectionism, a production subsidy is preferable to a tariff since it achieves this objective without interfering with the consumption decisions of local consumers who can still purchase the imported product at the free trade price pF. In Figure 1, the efficient way of achieving local production of xW units is the production subsidy β of per unit as opposed to an import tariff of the same magnitude.

But what if the policy objective of a country is to increase self-sufficiency or reduce reliance on imports of certain goods? We next address this key question.

3.3 The Pursuit of Self-Sufficiency

An important finding of existing literature is that for furthering the policy objective of self-sufficiency, an import tariff is a superior policy instrument to a production subsidy. Intuitively, for a small open economy, a subsidy encourages local production of the good but has no effect on local consumption since the foreign price of the good (as well as the local price) remains unchanged. By contrast, an import tariff encourages local production while simultaneously discouraging imports since it increases the local price of the good. As a result, an import tariff ends up being a more effective instrument for promoting self-sufficiency. In their canonical general equilibrium analysis of the issue, Bhagwati and Srinivasan (Reference Bhagwati and Srinivasan1969) show that not only is an import tariff superior to a domestic production subsidy for promoting self-sufficiency, but it is also the optimal policy instrument for achieving this objective.

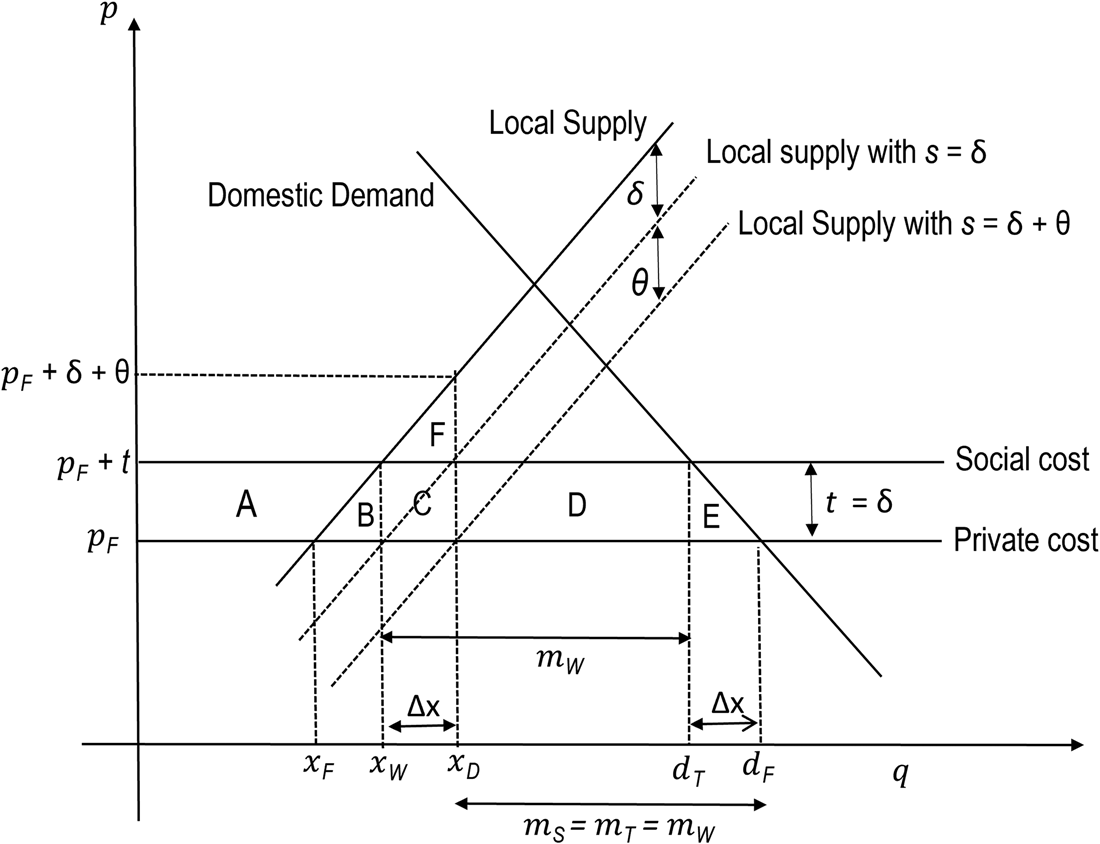

Figure 2 illustrates the comparison of a tariff and a subsidy when the local government's objective is to restrict imports because the social marginal cost of imports exceeds their private costs. This discrepancy is captured as follows: while consumers can import from abroad at price pF, the social costs of a unit of imports equals pF + δ, where the parameter δ captures the external damage inflicted by each unit of imports. In Figure 2, the free trade level of imports equals mF = dF–xF and local policy aims to reduce them to the welfare maximizing level mW = dT–xW, where mW < mF. The local government can meet this objective by imposing the tariff t under which consumption equals dT while local production equals xW, so that imports under the tariff equal the socially optimal level mW = dT–xW.Footnote 6

Figure 2. Limiting imports: tariff versus subsidy.

Note that a subsidy equal to δ fails to do the job since imports under it exceed the socially optimal level mW. To see why, note that production under the subsidy s = δ equals xW while consumption equals the same level as that under free trade (i.e., dF) so that imports under the subsidy equal dF–xW = mW + Δx, where Δx > 0. Thus, to deliver the socially optimal level of imports, the production subsidy must be higher than δ because it has to make up for the fact that the consumers continue to buy the same amount of the good as that under free trade.

To see this more clearly, suppose the domestic supply curve is qS = p/2 and the demand curve is qD = a–p/2. If the government imposes an import tariff of t, then local price becomes pF + t and imports equal mT = a–(pF + t)/2–(pF + t)/2 = a–pF–t. If the local policy is the production subsidy s instead of the tariff t, the local price remains pF and imports equal mS = a–pF–s/2. It follows immediately that for mS = mT, we must have s = 2t, i.e., the domestic production subsidy s needs to be twice as large as the import tariff t to yield the same level of imports. If s = t, imports under the production subsidy exceed those under the import tariff by the amount Δx = t–t/2 = t/2.

In Figure 2 the socially optimal subsidy equals sW = δ + θ. As the figure shows, when s = sW = δ + θ, imports equal mW. Since both the tariff tW = δ and the subsidy sW = δ + θ yield the socially optimal level of imports, they are equally effective in reducing the external damage caused by imports. The total benefit of reducing the external damage associated with imports is the same under both policies and it equals δ(mF–mW) = δ(dF–xF) + δ(dT–xW).

Given their equal efficacy in reducing imports, when comparing the two policy instruments tW and sW, we can ignore the external damage associated with imports and focus on the usual effects of these instruments on market participants (i.e., consumers and producers) and the government. In Figure 2, under the tariff t = tW = δ imports shrink from mF to mW and the local price increases from pF to pF + t so that consumers lose – (A + B + C + D + E), local producers gain + A, and the government collects tariff revenue equal to C + D. Thus, ignoring the benefit accruing from the reduction in the external damages caused by reduced imports, the net effect of the tariff on local welfare equals – (B + E).

Unlike a tariff, the production subsidy sW has no effect on local consumers since they continue to have the same level of consumption as under free trade. Due to the subsidy, local producers increase their output from xF to xW. Subsidy payments are simply a transfer from the government to the local industry so they do not affect total local welfare.Footnote 7 The net loss suffered by the local economy gross of the reduction in external damages of imports equals the total additional cost incurred by the local economy due to the expansion in production from xF to xD, i.e., – (B + C + F). These additional costs arise because whenever local output exceeds xF the local cost of production is higher than the free trade price pF.

Comparing the two policy instruments, we note that the tariff tW is preferable to the subsidy sW iff E < C + F, which is necessarily true since area C is a rectangle with the same base and height as the triangle E and is therefore twice as large as E (i.e., C = 2E). Thus, an import tariff is clearly superior to a production subsidy for achieving self-sufficiency in production. Furthermore, this conclusion holds even if imports generate no negative externality (i.e., δ = 0) and the government wants to reduce imports to mT for political-economy reasons: a tariff which reduces imports to mT is still preferable to a production subsidy which achieves the same outcome.

The maintained assumption in the above analysis is that the importing country cannot affect world price. But what if this is not the case? Figure 3 illustrates how the use of a tariff to restrict imports affects the importing country when its tariff alters the terms of trade in its favor. In Figure 3, free trade results in mF imports at price pF and local welfare equals the area of the triangle ADH minus the area of the parallelogram ABHG (which measures the total damage caused by imports mF). Thus, net welfare of the importing country under free trade equals the area of triangle BDI minus the area of triangle IHG. Accounting for the externality associated with imports calls for allowing only mW units of imports. Just like a small importer, a large importer can also achieve this outcome by imposing a tariff t = δ that equals the per unit damage associated with imports. The key new element is that the tariff also improves the larger importer's terms of trade by lowering the world price from pF to pT. Local consumers pay pT + t but do not bear the entire tariff since the decline in the foreign price from pF to pT shifts some of the tariff burden on to the shoulders of foreign producers.

Figure 3. Limiting imports via tariff for a large country.

Social welfare in the importing country under the tariff t = δ equals the area AFKE minus the area of the parallelogram ABFK (which measures the total damage caused by the socially optimal level of imports mW), which is simply the triangle BEK. Observe that since triangle BEK contains the triangle BDI within it, welfare under the tariff t = δ is strictly higher than that under free trade. Of course, the tariff t = δ simply neutralizes the damage associated with imports and is not the ‘fully optimal tariff’ for a large importer since such a tariff would also need to account for terms of trade effects and would therefore be higher.Footnote 8

3.4 Key Economic Message and Further Considerations

A major insight obtained from the economic analysis of non-economic objectives such as national security is that there is a subtle but significant difference between producing more of something locally and discouraging its imports or increasing self-sufficiency. If national defence considerations primarily require that the scale of output of a domestic industry exceeds some threshold level, production subsidies are the optimal instrument for fulfilling that objective. However, if a country is concerned that it has become overly reliant on a certain trading partner for securing a product to which it does not want to risk losing access, then the policy objective calls for encouraging domestic production and simultaneously reducing purchases from that trading partner, or simply put, reducing imports.Footnote 9 This objective is best met via an import tariff or a quota as opposed to a production subsidy to local industry. These results emerged from the classic theory of distortions according to which the first-best policies directly target the root causes of distortions that make the market equilibrium sub-optimal.

The analysis above considers national security from the perspective of encouraging domestic production and/or increasing self-sufficiency in a classical framework of competitive markets that are subject to externalities. While insightful, this framework does not address at least two relevant concerns. First, necessary imports may be produced by only a handful of foreign suppliers as opposed to many competitive ones. Second, as we noted earlier, national security considerations may call for inflicting economic damage on a specific industry in an enemy power to reduce the likelihood of aggression on its part. Under the former situation, it would be desirable for a country to ensure that it is not overly dependent on one or two suppliers for key products. Having multiple sources of supply could not only improve the terms at which imports can be purchased but also insure against the risk of losing access to the product if a specific supplier exits the market or withholds supply to potentially bargain for better terms or other strategic reasons. Policies aimed at diversifying the sources of critical foreign products fall outside the scope of traditional instruments, such as tariffs or subsidies that affect the level of production and trade but take market structure as given. But the basic idea is not that different: in the classical analysis, the only alternative source to producing the good locally is importing it from a trading partner, but clearly, one could also import it from a third country.

As far as inflicting damage on a foreign industry is concerned, a tax on foreign sellers (i.e., an import tariff) would directly reduce their profits and hurt their ability to survive in the marketplace. Of course, the problem with using an import tariff is that it would also hurt domestic consumers. Finally, if the foreign industry relies heavily on a domestic intermediate input to produce a final product, an export ban on the domestic intermediate could be potentially justifiable if national security calls for damaging the foreign industry. Under such a situation, it is conceivable that an export ban dominates a prohibitive tariff on imports of the final product from the foreign country if, for example, the ban causes the foreign industry to shut down by making production infeasible. By contrast, a prohibitive tariff on the foreign country's exports of the final good (with free trade in the intermediate market) would not hurt the foreign industry's ability to produce and sell the good in its own market or in third-country markets. We leave the formal analysis of these fascinating questions to future research.

With the preceding overview of the implementation of GATT Article XXI and the economic aspects of the pursuit of national security in hand, we now examine two major recent trade disputes where the United States invoked Article XXI in disputes involving its trade measures: US–Steel and Aluminium Products (Switzerland) Footnote 10 and US–Origin Marking (Hong Kong, China). Footnote 11

4. US Instruments and the Purported Aims

In both cases, US–Steel and Aluminium Products (Switzerland) and US–Origin Marking (Hong Kong, China), the respective panels never moved beyond identifying the situation as falling within the enumerated circumstances of GATT Article XXI(b)(iii) to evaluate the desired means and the US instruments chosen, as against the US's articulated essential security interests. In other words, the panels focused on the ‘when’ dimension, i.e., whether or not the US's usage of the GATT security exceptions conformed to any of the scenarios under which Article XXI permits a member to act. As elaborated in Section 3, both disputes engage different facets of the United States' essential security interests – questions of self-sufficiency and improved US steel and aluminium capacity utilization versus clarifying trade relations with another member owing to international rights concerns.

4.1 US–Steel and Aluminium Products (Switzerland)

All complainantsFootnote 12 believed that the dispute stemmed from specific investigations and actions taken under Section 232 concerning imports of steel and aluminium products, as described in two major reports of the US Department of Commerce:

a. ‘The Effect of Imports of Steel on the National Security: An Investigation conducted under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, as amended’, US Department of Commerce Report, 11 January 2018 (Steel Report), and

b. ‘The Effect of Imports of Aluminium on the National Security: An Investigation conducted under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, as amended’, US Department of Commerce Report, 17 January 2018 (Aluminium Report).Footnote 13

These reports identify the findings and determinations of the US Department of Commerce investigations into the effects of imports concerning steel and aluminium (per each report). Both Reports justify actions on the position that US ‘national defence includes both defence of the US directly and its ability to project military capabilities globally’. Additionally, the term ‘national security’, as understood by the Department of Commerce, refers to a broad consideration of the ‘general security and welfare of certain industries, beyond those necessary to satisfy national defence requirements that are critical to the minimum operations of the economy and government’.

The US Secretary of Commerce determined that the

displacement of domestic steel [and aluminium] by excessive imports and the consequent adverse impact of those quantities of steel imports on the economic welfare of the domestic steel [and aluminium] industry, along with the circumstance of global excess capacity in steel [and aluminium], were ‘weakening our internal economy’ and therefore ‘threaten to impair’ US national security as defined in Section 232.Footnote 14

The Steel Report (the Aluminium Report arrives at a similar conclusion) contains four main findings:

a) Steel is required for critical infrastructure and is used in strategic industries.

b) High import penetration adversely impacts the US steel industry by impacting prices and supply with adverse knock-on effects, including domestic steel mill closures and unemployment, rising trade actions, and loss of domestic opportunities.

c) The displacement of domestic steel by excessive quantities of imports weakens the US economy and limits the capacity available for a national emergency.

d) Global excess steel capacity contributes to the weakening of the US economy because free markets are ‘adversely affected by substantial chronic global excess steel production led by China’, and US steel producers face increasing import competition.Footnote 15

The Steel and Aluminium Reports offered alternative courses of action with global quotas, tariffs, or selected tariffs on a subset of countries.Footnote 16 In response to the two reports, former US President Donald Trump adjusted the level of imports by imposing quotas and/or tariffs on steel and aluminium products. The Trump administration intended to raise domestic steel and aluminium production to above 80% of capacity, the threshold by which the sectors would remain viable.Footnote 17 At the time, capacity utilization in the steel industry was under 75%, and the aluminium industry had a capacity utilization rate of under 45%.Footnote 18 In a series of presidential proclamations, the US President imposed additional import duties of 25% and 10%, respectively, on certain steel and aluminium imports from all countries, with various exemptions granted to selected WTO members, introduced import quotas on steel and aluminium imports from specific countries, and imposed additional import duties on steel imports from Turkey to 50%.Footnote 19

Each complainant submitted their assessments of the legal instruments that constitute the US measures. For example, Switzerland challenged the legal instruments that implemented import duties, country exemptions, and product exclusions. Furthermore, Switzerland did not directly challenge Section 232. Still, it argued that US authorities had ‘repeatedly interpreted’ Section 232 in a manner that was ‘inconsistent with the United States’ obligations under the covered agreements’. In contrast, in US–Steel and Aluminium Products (Norway), Norway challenged ‘four sets of measures’ that entailed (i) the import tariffs, (ii) import quotas, (iii) country-wide tariff exemptions, and (iv) product exclusions.

In addition, the complainants in the US–Steel and Aluminium Products disputes argued that the Section 232 measures are safeguard measures and are inconsistent with obligations under GATT Article XIX and the Agreement on Safeguards.Footnote 20 The US disputed the applicability of these obligations, arguing that its defence lies in GATT Article XXI – the Agreement on Safeguards is inapplicable to the Section 232 measures by virtue of Article 11.1(c) of that Agreement as the measures were ‘sought, taken, or maintained’ pursuant to GATT Article XXI, not Article XIX.Footnote 21 In assessing the applicability of the Agreement on Safeguards the panel looked at whether the Section 232 measures were ‘sought, taken, or maintained pursuant to Article XXI of the GATT 1994’ within the meaning of Article 11.1(c) of that Agreement.Footnote 22 On review of the relevant evidence of the measure's design and application and the US characterization of the measures in its communications to WTO bodies, the panel found the Section 232 measures were ‘pursuant to’ a provision ‘other than’ Article XIX within the meaning of Article 11.1(c) of the Safeguards Agreement.Footnote 23

After having distinguished a review evaluating action ‘pursuant to’ Article XXI and action ‘consistent with’ Article XXI, the US–Steel and Aluminium Products (Switzerland) panel turned to the consistency of the US invocation of the GATT security exceptions.

4.2 United States – Origin Marking Requirement

In this dispute, Hong Kong, China challenged the requirements applied by the US as published in the US Customs and Border Protection (USCBP) in the Federal Register Notice of 11 August 2020 that states imported goods ‘produced in Hong Kong … may no longer be marked to indicate “Hong Kong” as their origin but must be marked to indicate “China”’Footnote 24 Such action is taken according to the Executive Order on Hong Kong Normalization of 14 July 2020.Footnote 25

Hong Kong, China complained, among other things, that the US measure was discriminatory, as the US had adopted no similar conduct towards other WTO members. Hong Kong, China challenged the US measures under the Agreement on Rules of Origin (ARO), the Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT Agreement), and the GATT.Footnote 26 At the centre of the dispute was Executive Order 13936 which suspended the applicability of section 5721(a) to title 22 of the US Code to the customs marking statute found in 19 USC sec. 1304. The Executive Order required that Customs and Border Protection should no longer apply US laws to goods produced in Hong Kong, based on the finding that Hong Kong, China was ‘no longer sufficiently autonomous to justify differential treatment in relation to [the People's Republic of China] under the particular United States laws’.Footnote 27

Based on the new policy, as specified in the Executive Order and reiterated in the Federal Register notice, the USCBP rejected the use of the words ‘Hong Kong’ in the required mark of origin after 9 November 2020 (including ‘Hong Kong, China’ or ‘Made in China – Hong Kong’).Footnote 28 After 9 November 2020, the US authorities required the mark of ‘China’ to be applied to the customs territory of Hong Kong, China, and the People's Republic of China to determine the country of origin for duty and other customs purposes.Footnote 29 The measure's rationale provided to the Hong Kong Trade Development Council was that ‘[t]he reference to Hong Kong under the current policy may mislead or deceive the ultimate purchaser as to the actual country of origin of the article and, therefore, is not acceptable for purposes of 19 USC. sec. 1304’.Footnote 30

The US argued that its measures were a response to ‘a threat to the essential security of the United States’.Footnote 31 The US raised, yet again, and unsurprisingly so, its proverbial argument that Article XXI is non-justiciable and that the security exceptions are self-judging. To the US, a WTO panel could take note of, but not review, the US invocation of all security exceptions.Footnote 32

The US decision to invoke the GATT essential security exceptions created a new challenge for the panel. Hong Kong, China wanted the panel to consider its claims under the ARO and TBT Agreement before proceeding to the GATT.Footnote 33 Yet, the US presented only one legal argument in response – total authority to invoke GATT Article XXI. If the panel consented to Hong Kong's sequence of arguments, it would need to establish the connection between the GATT security exceptions and other WTO agreements, such as the ARO and the TBT Agreement.Footnote 34 However, the panel concluded it would first turn to Hong Kong, China's claims under Article IX:1 of the GATT, and through this decision, its choice to consider first the reviewability of action under Article XXI(b) of the GATT.Footnote 35

The panel rejected the US claim, stating that the negotiating record pointed to no common understanding regarding the self-judging nature of the term.Footnote 36 Having rejected this claim, the panel went on to find that the US was in violation of Article IX.1 of the GATT, requiring WTO members to treat all other members in a non-discriminatory manner concerning marking requirements. The panel found that this had not been the case as, unlike what the US had been practicing with respect to imports from other WTO members, there was no correspondence between the determination and the marking of origin of products.Footnote 37 As a result, Hong Kong, China had suffered damage since its exports could not benefit from the reputation of products originating in its territory.Footnote 38 As discussed below, the panel found the US failed to justify its measure under Article XXI(b) of the GATT.Footnote 39

5. Panel Assessment of the US Security Measures

Owing to the potentially wide scope of measures that may fall under the security exceptions, the case law confirms a general uneasiness regarding discerning good faith invocations from those based on bad faith and opaque invocations of security. Without clearly setting out members' burdens of proof or the appropriate standard of review, the US–Origin Marking (Hong Kong, China) and US–Steel and Aluminium Products (Switzerland) panel reports assessed US actions taken in an emergency in international relations in accordance with Article XXI(b)(iii) of the GATT.

What were the core issues underlying these disputes? In the case of US–Origin Marking (Hong Kong, China), the US determination of a security threat was due to the undermining of the Hong Kong autonomy based on the actions of the People's Republic of China. In the case of US–Steel and Aluminium Products (Switzerland), the inability of US domestic steel and aluminium producers to compete with imports led to several knock-on effects that included reduced domestic capacity. Does the text of Article XXI(b)(iii) require a panel to assess whether the US trade tools could plausibly relate to the articulated security interests? Both answers depend on properly identifying the international situation before proceeding to evaluate policy actions. In other words, the assessment must begin with a ‘when’ and not a ‘how’.

As this section will show, these panel reports have attempted to fix the boundary between ‘trade’ and ‘essential security interests’, even if the boundary today has become a spectrum along which members may move depending on their goals. Fleshing out the limits of Article XXI through such disputes is essential to the future design of managing mixed security and economic objectives.

5.1 Tailoring Means to Ends

GATT Article XXI(b) does not clearly set out the appropriate level of deference to a respondent member regarding its security measures taken. All existing WTO panel reports must begin with theory to establish a baseline for weighing a member's trade interests derived from the benefits of WTO commitments and any essential security interests.Footnote 40 The first WTO panel report for Russia–Measures Concerning Traffic in Transit (Russia–Traffic in Transit) would be the inevitable starting point, even if it left several issues for future review.Footnote 41

Subsequent panels have read the Russia–Traffic in Transit panel report as adopting a two-tier standard of review for GATT Article XXI(b)(iii), whereby:

• It would first ask whether the challenged measures had been adopted during wartime or emergency in international relations (understood as a war-like situation);

• If yes, the challenged measures would not be disturbed if they were ‘minimally plausible’, that is, if they were inappropriate to serve essential security interests;Footnote 42

• If not, then the plaintiff would prevail.Footnote 43

However, there is greater nuance in the two-tier review set out in the Russia–Traffic in Transit panel report. The Russia–Traffic in Transit panel defined the circumstances falling within the scope of subparagraph (b)(iii) but left it unclear whether or what types of economic disputes may also be ‘serious security-related conflicts’.Footnote 44 A key imperative of the Russia–Traffic in Transit panel was to root its assessment in members’ efforts to separate economic and trade interests from ‘military and serious security-related conflicts’.Footnote 45 The logic of this conclusion supported the attention to deterring abuses of the exceptions, e.g. to shield protectionist measures. Yet, it was clear that Russia's economic and military security interests motivated its actions. A primary legal instrument for the Russian measures is the Decree of the President of the Russian Federation No. 1 of January 2016, which states that the measures are to ‘ensure the economic security and national interests of the Russian Federation in international cargo transit’.Footnote 46 However, it is unclear whether future assessments of the security exceptions must unpack the segregation of economic and security considerations, though nothing within the text requires the actions to be strictly non-economic.

In line with this argument, reconsider the Russia–Traffic in Transit panel report. The panel set place holder interests by finding that situations ‘refer generally to a situation of armed conflict’ and therefore ‘give rise to … defence or military interests, or maintenance of law and public order interests’.Footnote 47 The Russia–Traffic in Transit panel used this to evaluate Russia's identification of the emergency at issue. However, it then returned to Russia's interests, finding that Russia's articulation of these interests depends on the emergency at issue: ‘the less characteristic is the “emergency in international relations” invoked by the Member … the less obvious are the defence or military interests … generally expected to arise’.Footnote 48 In a dispute, the further apart the international emergency is from the obvious ‘hard core’ of war then, in turn, the more specificity the defendant must provide to articulate its impacted essential security interests. Therefore, the crux of the Article XXI assessment lies in whether the defendant, subject to an obligation of good faith, can adequately articulate its essential security interests based on the emergency at issue.Footnote 49 It is impossible to assess the situation without first identifying the interests implicated. In other words, a panel must consider the plaintiff's interests in this dispute to assess whether these interests were sufficient to establish an emergency in international relations. This analysis does not suggest loosening the requirements to use Article XXI exceptionally. Rather, it presents a more holistic balancing of the rights and obligations of these exceptions.

Finally, as elaborated below, this panel report confirms that members may not wholly ‘self-judge’ the invocation of GATT Article XXI. The level of deference accorded to a member when evaluating the ‘plausibility’ of actions is dependent upon the member's articulation of its ‘essential security interests’.Footnote 50 However, as detailed below, this question only arises if an invoking member passes the first threshold of identifying the ‘when’ in these cases – e.g., a situation ‘very close to the “hard core” of war or armed conflict.Footnote 51

What remains unclear from the existing case law are more complex questions as to how governments anticipate, or even preempt, the total breadth of the ‘when’ a member takes security actions in times of ‘emergency in international relations’, even in the context of a traditional understanding of war and conflict. Section 5.3 addresses questions regarding risk aversion and anticipating war.

5.2 Self-Judging GATT Article XXI(b) and the Order of Analysis

The first question that arises is whether Article XXI is self-judging. Indeed, the US had maintained that GATT Article XXI is wholly self-judging and, therefore, excludes any review of the challenged measures.Footnote 52 Asserting the self-judging nature of GATT Article XXI enabled the US to argue in US–Steel and Aluminium Products (Switzerland) that ‘any and all of the three circumstances described in the subparagraphs [of Article XXI] are present’.Footnote 53 The Russia–Traffic in Transit panel had, already, thwarted this claim. The US–Steel and Aluminium Products (Switzerland) panel could have reviewed the matter by asking one question: Was an approach different from that in Russia–Traffic in Transit warranted, and if so, why? It declined (most likely, on purpose) to do so and decided to assess the legitimacy of US actions as if this was the first time a WTO panel faced a defence based on GATT Article XXI. In contrast, the US–Origin Marking (Hong Kong, China) panel acknowledged that Hong Kong, China defined the legal standard of GATT Article XXI(b) based on the Russia–Traffic in Transit panel but proceeded to develop its own order of analysis.Footnote 54

The self-judging argument proved challenging for these panels in a rather particular way – the US was not forthright in identifying the specific subparagraph on which it based its security defence under Article XXI(b). According to the US in US–Steel and Aluminium Products (Switzerland), its burden of proof ‘is discharged once the Member indicates, in the context of dispute settlement, that it has made such a determination’ that it considered ‘one or more of the circumstances set forth in Article XXI(b) to be present’.Footnote 55 These disputes reveal that the complainants (and panels) shared a frustration – but forced acceptance – of the US's ambiguous acknowledgement during the proceedings that ‘publicly available information’ on the record ‘most naturally’ relates to GATT Article XXI(b)(iii) in both cases.Footnote 56 No panel elaborated on the impact of the US's belated identification of the circumstances upon the complainants’ position regarding what requires rebutting.

The two panels discussed here refuted the US claim that Article XXI was self-judging (following Russia–Traffic in Transit in this respect), and then the next question regarded the allocation of the burden of proof. Turning to prior case law, the burden of proof was a crucial issue in the Russia–Traffic in Transit dispute. Russia did not disclose information about the ‘emergency in international relations’. Instead, Russia formulated ‘hypothetical circumstances’ and cited Ukraine's Trade Policy Review Report to identify the ‘emergency in international relations’.Footnote 57 Ukraine maintained throughout the proceedings that Russia could not invoke Article XXI(a) to refuse to disclose any factual evidence and evade its burden of proof.Footnote 58

The Russia–Traffic in Transit panel did not set an onerous evidentiary burden on Russia and accepted that the ‘situation’ giving rise to the measures was ‘publicly known’.Footnote 59 Yet, the panel did not rule on Russia's invocation of Article XXI(a) when failing to provide any factual evidence or legal arguments related to its invocation of subparagraph (b) of that same provision. Critics observed that though the panel retains the authority to seek information to fulfil its duty in the dispute, it must explain the respondent's Article XXI protections to preserve the complainant's rights in the proceedings (Crivelli and Pinchis-Paulsen, Reference Crivelli and Pinchis-Paulsen2021, 588; Van Damme, Reference Van Damme and Bethlehem2022, 741).Footnote 60

After Russia–Traffic in Transit, Saudi Arabia refused to engage with ‘the facts or arguments presented by Qatar’ in the Saudi Arabia–IPRs dispute.Footnote 61 As a result, the panel clarified that it must ‘satisfy itself’ that the complainant made a prima facie case in relation to each claim. The panel evaluated whether the claims were ‘well-founded in fact and in law through various means, including written and oral questions and undertaking a careful review of the evidentiary basis underlying Qatar's various factual assertions’.Footnote 62

As to the order of analysis, the Saudi Arabia–IPRs panel departed from the Russia–Traffic in Transit panel's approach of first examining whether Russia's measures fell within the scope of GATT Article XXI(b)(iii).Footnote 63 Instead, it adhered to ‘common practice’. It decided the complainants first must show that a violation of a GATT provision before the burden would shift to the respondent to justify its actions through the invocation of Article XXI.Footnote 64 The US–Steel and Aluminium Products (Switzerland) panel maintained the Saudi Arabia–IPRs panel's approach, first evaluating the WTO consistency of the US security measures.Footnote 65 The US–Origin Marking (Hong Kong, China) panel also arrived at this order of analysis, but only after first establishing that GATT Article XXI is not entirely self-judging.Footnote 66

Ultimately, there are systematic implications of the US ‘self-judging’ argument. Declining to isolate the ‘when’ a security measure occurred may be a product of the United States' refusal to have a WTO panel conflate the ‘when’ with the ‘why’ question – better understood as probing the ‘necessity’ of action taken under GATT Article XXI. The phrase ‘which it considers’ sets the scope of Article XXI(b), which the Russia–Traffic in Transit panel found only qualifies what actions are ‘necessary’ when protecting essential security interests (in other words, this is the element that is self-judging).Footnote 67 Notwithstanding this finding, the Russia–Traffic in Transit panel inherently curtailed this discretion when it found that the obligation of good faith imparted a minimum requirement of plausibility when examining the emergency at issue and the measures imposed in response.Footnote 68 Therefore, though the Russia–Traffic in Transit panel found ‘no need to determine the extent of the deviation of the challenged measure from the prescribed norm’ to evaluate ‘necessity’, it evaluated whether the articulation of Russia's essential security interests was ‘minimally satisfactory’ in the circumstances.Footnote 69

Likewise, the Saudi Arabia–IPRs panel disciplined the invoking member's discretion with the review outlined by Russia–Traffic in Transit. It found that Saudi Arabia's authorities non-application of criminal procedures and penalties to a commercial-scale broadcast pirate, beoutQ, failed to have ‘any relationship’ to its stated objective of ending all interactions between entities in Saudi Arabia and Qatari nationals (necessary to protect its essential security interests).Footnote 70 Thus, albeit discretely, the Saudi Arabia–IPRs panel did accord attention to evaluating ‘how’ a measure can best meet its desired objective.

5.3 The Meaning of ‘in Time of … Emergency in International Relations’

As stated, all WTO disputes to date focus solely on GATT Article XXI:b(iii) invocations, where members acted during an ‘emergency in international relations’. Beginning with Russia–Traffic in Transit, the panel emphasized that the idea of ‘war’ informs the broader category of ‘emergency in international relations’. Equally important, the Russia–Traffic in Transit panel found that Article XXI(b)(iii) does not capture ‘political or economic conflicts … unless they give rise to defence and military interests, or maintenance of law and public order interests’.Footnote 71 Only particular interests would rise in response to ‘a situation of armed conflict, or of latent armed conflict, or of heightened tension or crisis, or of general instability engulfing or surrounding a state’.Footnote 72 The Russia–Traffic in Transit panel emphasized situations of ‘danger … that arises unexpectedly and requires urgent action’. Relying on UN documents, the Russia–Traffic in Transit panel found that the international community acknowledged an emergency existed between Russia and Ukraine.Footnote 73

In comparison, the Saudi Arabia–IPRs panel evaluated the existence of an ‘emergency in international relations’, finding agreement with Saudi Arabia that severance of all diplomatic and consular relations is the ‘ultimate state expression of the existence of an emergency in international relations’.Footnote 74 The panel did not opine on the burden of persuasion or proof required to determine the existence of an ‘emergency in international relations’.Footnote 75 Nor did it opine on the legal test when a panel does not find an emergency exists.Footnote 76

Most importantly, the Saudi Arabia–IPRs panel did ‘not consider’ the existence or extent of cooperation between the disputing parties because ‘the complete severance of diplomatic, consular, and economic relations … remained essentially unchanged’ to the present day.Footnote 77 As assessed below, this criterion would become central to evaluating an ‘emergency in international relations’ within sub-paragraph (b)(iii) of Article XXI for the US cases.

Finally, Pinchis-Paulsen (Reference Pinchis-Paulsen2020) has delved into the negotiating record and found that the construction of this sub-paragraph anticipated a narrow set of circumstances closely tethered to wartime. The drafters settled on the more ambiguous ‘emergency in international relations’ over the alternative of ‘imminent war’. The record, thus, suggests a relatively narrow understanding, in line with the prevailing practice in the 1940s.Footnote 78 Things have changed since then, but the members have yet to adapt the text of Article XXI.Footnote 79

5.3.1 Evaluating the Emergency in US–Steel and Aluminium Products (Switzerland),

Like the earlier panels in Russia–Traffic in Transit and Saudi Arabia–IPRs, the US–Steel and Aluminium Products (Switzerland) panel observed that the circumstances of ‘emergency in international relations’ in the sense of subparagraph (b)(iii) of GATT Article XXI must be ‘equally grave or severe’ to ‘war’ in terms of the impact on international relations.Footnote 80 The panel decided the circumstances must subscribe to this ‘severity’ to properly balance the rights and obligations reflected in GATT Article XXI.Footnote 81

In contrast, the US disagreed that it must show the ‘gravity or severity’ of an ‘emergency in international relations’. It interpreted the phrase as a ‘situation of danger or conflict, concerning political or economic contact, occurring between nations, which arises unexpectedly and requires urgent attention’.Footnote 82 The US relied on the Steel and Aluminium Reports to argue that China's steel production harmed US domestic capacity and exacerbated global excess steel capacity.Footnote 83 Both, the US argued, posed a threat to US national security. It supplied these reports as evidence of an urgent international situation engaging global concerns whereby coordination among ‘steel-producing nations’ failed to provide a solution to steel excess capacity. Accordingly, the United States acted at a ‘crucial point’.Footnote 84 Without ‘immediate action’, the US steel industry would ‘suffer’ damages that ‘may be difficult to reverse’; or face a time where the industry would be unable to address future ‘national emergencies’.Footnote 85

The panel rejected the US assessment, finding that the US equated domestic legal standards to the legal bases of the WTO-covered agreements.Footnote 86 Specifically, the panel found US concerns with its domestic situation were inapplicable to an assessment into ‘an international situation’ – in this case, of global excess capacity in steel and aluminium.Footnote 87 Thus, all factual evidence or legal arguments ‘relating to the domestic situation of steel and aluminium industries in the United States’ failed to prove the existence of an ‘emergency in international relations’ within the meaning of the GATT Article XXI(b)(iii).Footnote 88

The panel's findings were rooted in a rejection of the self-judging argument presented by the US. The panel did not render its conclusions based on a more exacting probe into whether members can invoke the GATT security exceptions to anticipate security concerns (like war) – via risk calculations and security preparedness. Nor did the panel weigh in on whether a threat to essential security interests could constitute an ‘emergency in international relations’ to justify GATT-inconsistency. And, of course, the panel never comes to evaluate if the US articulated its security interests considering the evidence and the domestic legal bases of the Section 232 measures. Counter-intuitively, had the US abandoned its self-judging arguments, there may have been more scope to assess the ends and means of supply security policies to protect US interests. Ultimately, the emphasis on the gravity of tensions between members flattens more complex questions about the complex reality of essential security, even the temporal dimensions of ‘when’, and certainly abandons the questions of ‘what’ actions are appropriate.

5.3.2 Evaluating the Emergency in US–Origin Marking (Hong Kong, China)

Like US–Steel and Aluminium Products (Switzerland), the US–Origin Marking (Hong Kong, China) panel stressed the quality of the situation for identifying the circumstances as falling under GATT Article XXI(b)(iii). Hong Kong, China asserted that the panel must objectively assess whether the situation ‘directly implicate[s] defence or military interests, or maintenance of law and public order interests’ (citing the findings of the Russia–Traffic in Transit panel report).Footnote 89 In contrast, the US argued that the situation is inseparable from a judgment about a state's essential security interests. Assigning a measure of severity or gravity to the situation or finding the emergency necessarily implicated defence or military interests were ‘non-textual’ readings of GATT Article XXI.Footnote 90 Asserting unilateral determination as to what interests tripped GATT Article XXI, the US asserted the text created no limits on essential security interests, including a requirement of ‘the protection of its territory and its population from external threats’.Footnote 91 It was sufficient for the US to notify the panel of a destabilizing situation that implicated its essential security interests to invoke GATT Article XXI.Footnote 92

The US–Origin Marking (Hong Kong, China) panel rejected a strict requirement that an emergency in the sense of GATT Article XXI(b)(iii) ‘necessarily involve defence and military interests’, even if such interests are ‘normally’ implicated.Footnote 93 The US–Origin Marking (Hong Kong, China) panel ‘refrain[ed]’ from opining on the interests involved, consciously distinguishing its assessment from Russia–Traffic in Transit.Footnote 94 Yet, in doing so, it eliminated the importance of understanding how the interests dictate the circumstances (and whether actions were taken in good faith). While the panel offers its own understanding of the threshold required to be an international relations emergency, it does silence the Russia–Traffic in Transit panel's efforts to turn these elements from fixed boundaries into a spectrum. With this in mind, the panel stated that the phrase ‘emergency in international relations’ must represent ‘a breakdown or near breakdown in the relations between states’.Footnote 95

The panel turned to the US evidence and arguments, stating that the US identified an ‘erosion of freedoms and rights of the people in Hong Kong, China, as well as the institutional degradation of democracy in Hong Kong, China’.Footnote 96 Further, the matter involved the relations of the US, China, and Hong Kong, China (and other members) and the relations between China and Hong Kong, China.Footnote 97 The panel evaluated four categories of US evidence: US domestic instruments; reports and statements by US officials on the situation in Hong Kong, China; other Members’ views; and press reports. It concluded that the US evidence did not clarify the threats to US security arising from the Government of China and Hong Kong, China authorities’ actions concerning human rights and freedoms of people in Hong Kong and the autonomy of Hong Kong.Footnote 98

Evaluating the factual evidence, the panel found that the situation failed to meet the requisite level of gravity to constitute an emergency in international relations under GATT Article XXI(b)(iii).Footnote 99 The core logic of the US–Origin Marking (Hong Kong, China) panel's conclusion reflects its attention to the relations at issue. The panel depicted the US and Hong Kong, China relations as binary – either off or on. It concluded that for an emergency to impact the US's essential security interests, the US must show that its relations with Hong Kong, China had reached a ‘point of breakdown’ to constitute an emergency in international relations.Footnote 100 Only exceptional circumstances, such as the severance of all diplomatic, consular, and economic relations with Hong Kong, China, would constitute an emergency in international relations under Article XXI(b)(iii).Footnote 101 In its assessment of the evidence, the panel was unconvinced that the requisite high threshold for invoking GATT Article XXI was met due to the selectivity of the US measures – targeting specific aspects of relations between Hong Kong, China and the US. To elevate the exceptional nature of the security exceptions, the panel report adds a notable and new clarification to past panels’ interpretations of Article XXI(b)(iii): to identify an international emergency, a member must show exhaustive actions to sever all relations with a member to invoke this WTO security exception properly.

Yet, embedded in the US–Origin Marking (Hong Kong, China) panel's assessment is another requirement: the US must demonstrate that such a breakdown had also occurred between the US and China. The panel noticed how the US and other members responded to events in Hong Kong, China, with measures taken vis-à-vis Hong Kong, China.Footnote 102 The panel called attention to the fact that ‘there is no evidence before us that there were measures taken vis-à-vis China’.Footnote 103 Here, the panel pointed out that though US arguments reflect actions taken to respond to China, no evidence enabled the panel to assess US–China relations. Even when comparing the situation in Russia–Traffic in Transit and Saudi Arabia–IPRs, the panel observed that the US condemnation of human rights abuses and threats to democracy never led to a ‘total collapse’ of relations between the US and Hong Kong, China (and China).Footnote 104

Finally, the panel applied a two-tier assessment to the US invocation of GATT Article XXI(b)(iii) – inevitably in line with the framework captured in earlier disputes. However, the panel cemented a stricter analytical framework by demanding fractured (or very nearly fractured) international relations. The strict adherence to this element fails to generate a pathway back to the ambitions of restoring balance in trade among members through WTO dispute settlement.Footnote 105 The US–Origin Marking (Hong Kong, China) dispute is a solid example of why this is the case.

6. The Missing Middle

Thus far, the WTO panel reports interpreting GATT Article XXI(b)(iii) suggest that a WTO-consistent invocation of security must come at the close of a security-raising situation – not before or during. The panels’ interpretation of an ‘emergency in international relations’ within the meaning of subparagraph (b)(iii) now translates into an international situation that demands an end to all international cooperation between affected members.Footnote 106 Further, the panel's interpretation confirms that a domestic situation cannot be the basis for justified security measures. If a member invokes Article XXI(b)(iii) to improve self-sufficiency, the impetus to do so must stem from necessary actions at a time of an international emergency between two or more members.

In the reports discussed here, the panels found that the US had identified international concerns but not a situation that could be characterized as an ‘emergency in international relations’. In US–Origin Marking (Hong Kong, China), the US had failed to demonstrate how concerns over the autonomy of Hong Kong, China impacted international relations – whether the relations between the US and China, China and other WTO members, or even between China and Hong Kong, China. In US–Steel and Aluminium Products (Switzerland), US evidence suggested a concern with excess global capacity in the steel and aluminium sectors. Still, the panel found no evidence that such a concern implicated two (or more) members’ relationships – let alone that the evidence satisfied the high threshold of near or total breakdown. As the analysis stopped at the first tier, none of the panels proceeded to evaluate the US articulation of its essential security interests based upon the circumstances that gave rise to them.

Separating the analysis of GATT Article XXI into two tiers creates a strict assessment of the circumstances giving rise to the essential security interests. Yet, collectively, these panels imposed a ‘gravity of breakdown’ requirement without first scrutinizing the articulation of essential security interests – contorting around the topic when it clearly helps explain the context for actions taken. Overall, the limited evidence supplied by the US rendered it difficult to evaluate the ‘how’ of WTO-consistency of its security measures (in any of these disputes). Still, the legal assessment of subparagraph (b)(iii) suggests a desire to catch within the ‘objective’ review all potential, undesirable expansions that rightly would step on the invoking member's subjective purview. However, the desire to curtail abuse of the security exceptions silenced questions about the relationship between the interests at issue, the scope of actions taken, and the reasons underlying the security concerns. In the wide chasm that separates protectionism from war lies a great deal of ambiguity.Footnote 107

History shows how essential security of supply was to the early years of the GATT and the Cold War (McKenzie, Reference McKenzie2020). However – crucially – this did not detract from parallel concerns about unravelling the multilateral trading system with too broad an outlet for deviating from GATT commitments (Pinchis-Paulsen, Reference Pinchis-Paulsen2020, 129, 140–142). Moreover, Pinchis-Paulsen (Reference Pinchis-Paulsen2023) argues that archival research of the early Cold War shows how security was never exceptional to the foundations of trade institutions but was a structural feature that helped organize the competitive conditions among strategic resources and goods. She examines two case studies where the US used trade to fulfil its foreign economic policies in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Both case studies detail how the US carefully engineered legal principles, used different techniques to regulate trade among allies, and simultaneously relied on discriminatory practices against rivals. As history demonstrates, US trade policy never separated economics and security. Accordingly, by learning from history, the US and other states can reposition legal debates on pursuing multi-dimensional security imperatives while fostering strategies sensitive to how multilateral coordination can help sustain alliances with trade.

For now, we suggest a close evaluation of early grappling with the borders of economics, and security reveals how governments used formal and informal approaches to broach questions of military potential, self-sufficiency, and strained diplomatic relations with trading partners – and such outlets remain accessible today. In other words, the economic and legal analysis presented here suggests a progression from Article XXI's ‘when’ aspects of gatekeeping the (ab)use of security exceptions to seizing opportunities to utilize the spectrum between trade and security policies – get to the ‘how’ as a starting place for members to coordinate trade and security objectives.

The current interpretation of GATT Article XXI(b)(iii) does not delve into other relevant legal issues, such as the form and the durability of the security measures – e.g., do they necessitate temporary action or a permanent response? Is the object of the measure clearly identifiable? Is the intention to eliminate global overcapacity (suggesting the need for a multilateral solution), to prevent the dominance by one member of capacity (or, more generally – economic competitiveness), or to gain a monopoly over the manufacturing or production of strategically important products? These questions disregard the gravity of a crisis in international relations but highlight the relationship between means and ends.

Sub-paragraph (b)(iii) of Article XXI does not explicitly commit to reviewing the relationship of means and ends of trade measures. To date, no WTO dispute settlement panel has clarified the scope of sub-paragraph (b)(ii) of Article XXI, which refers to ‘traffic in arms, ammunition, and implements of war’ and to ‘such traffic in other goods and materials as is carried on directly or indirectly to supply a military establishment’. Nor have we seen how export controls or conservation of resources may engage security issues under GATT Articles XI and XX. In the future, a defendant may see fit to invoke these provisions, and, in any event, a panel may need to abandon the earlier dissection of subparagraph (b)(iii) to assess both the ‘when’ and the ‘what’ of an Article XXI invocation if the WTO is to remain relevant in today's geopolitical environment.Footnote 108

7. Conclusion

The panels for US–Steel and Aluminium Products (Switzerland) and US–Origin Marking (Hong Kong, China) did not follow the approach advocated in this paper. Instead, the two panels fixed on whether the challenged measures occurred during a war or a war-like (emergency) situation. But what qualifies as an ‘emergency’ depends on observable and non-observable elements. Undoubtedly, Russia's attack on Ukraine created an international emergency. But were Iran's plans to develop nuclear weapons widely known before the Stuxnet story broke out? Consequently, in our view, a major unresolved question in both disputes is: What exactly was the US trying to protect through its measures? National security is not a self-defining concept, and dis-aggregating it is the only way an adjudicator can assess the appropriateness of the challenged measures, especially from the perspective of achieving the intended objective(s). If the plaintiff or the panel had asked this question, the US might have had to explain the nature of the ‘emergency’ facing it and why it was appropriate to address it in the way it did.

Even though the reports confirm that GATT Article XXI is not wholly self-judging, the panels adopted a deferential standard of review. Nevertheless, the current state of play certainly needs improvement. For starters, the legal text itself is wanting, as ‘essential security’ is anything but well-defined. While the negotiating record can provide some guidance, and Pinchis-Paulsen's (Reference Pinchis-Paulsen2020, Reference Pinchis-Paulsen2022) analysis has further clarified this point, WTO panels have yet to delve deeply into the depth of its meaning.

Unless the critical term ‘essential security’ is disaggregated and sharpened, future panels cannot determine the appropriateness of measures used. However, dis-aggregating the concept of ‘essential security’ is only the first step towards examining the justification of invoking Article XXI in a particular context. The logical next step ought to be the evaluation of the appropriateness of the measure adopted. In our view, appropriateness implies a rational connection between means and ends. To be considered reasonable, the measure(s) adopted must contribute towards achieving the stated objective. A secondary evaluation criterion within this context could be whether the measures adopted significantly contribute to achieving the stated objective. Recall that Johnson's (Reference Johnson1960) analytical framework strongly suggests that when a state undertakes an economic policy action to promote national security, it is almost inevitable that some economic inefficiencies will arise. By pursuing a salient non-economic objective (such as national security), states reveal that they value the attainment of that objective over other objectives that might be worth pursuing, including the maximization of national income.

Alas, considering the reasoning adopted by the two panels, we find it difficult to go any further with our line of analysis. Since the panel did not ask the US to disaggregate its objective and explain how its chosen measures helped achieve it, it is impossible to second-guess what it really might have been and whether the chosen measures were justifiable. As our economic analysis highlights, even the subtly different objectives of ‘encouraging domestic production’ and ‘reducing imports’ call for fairly different policy interventions: while trade restrictions are justifiable for meeting the second objective, production subsidies are first-best for the second scenario.

It remains to be seen whether the legal test for evaluating claims under Article XXI, as expressed in Russia–Traffic in Transit, only makes good sense in cases of armed conflict that give rise to traditional, military or defence interests. After studying US–Origin Marking (Hong Kong, China) and US–Steel and Aluminium Products (Switzerland), we know that panels have (either directly or implicitly) scrutinized sub-paragraph (b)(iii) to control for abuse and to separate ‘security’ and ‘trade’ disputes.Footnote 109 Yet, it is time to look past the tiered structure of GATT Article XXI and recognize that a truly ‘objective’ assessment demands pliability and engagement with all the elements contained in the GATT – the security and economic elements of trade policy. Such a review would be the only way to guarantee that the legal interpretation is not primarily a function of a panel's subjective evaluation.

Finally, one might question whether panels are well-equipped to deal with security disputes. The recent experience shows an almost mechanistic implementation of a simple two-tier test. But how would panels deal with a case of export restrictions of sensitive material to China, a ‘systemic rival’ for both the EU and the US as per their recent official declarations? Can this test do justice to the objective function of Article XXI? Hoekman et al. (Reference Hoekman, Mavroidis and Nelson2023b) have recently added their voices to the pool of critics.Footnote 110 That said, Pinchis-Paulsen (Reference Pinchis-Paulsen2023) suggests more work needs to be done concerning mixed trade and security imperatives in the GATT era before making any conclusions as to the limits of today's multilateral institutions. History may provide clues as to how to develop international coordination and cooperation despite governments' increasing invocations of security rationales to justify exceptional measures. We believe that further discussion of how to handle security issues at the WTO should be a priority issue for its membership.