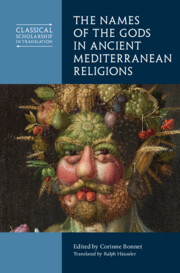

From Shadows to Dawn: Names as a Sign System

Figure 1.0 Zeus: detail of the colossal marble statue discovered at Aigeira in Achaia, second century bce

In the Aravaipa Canyon in Arizona, on 30 April 1871, more than 100 Apache men, women and children were massacred by a group of American, Mexican and (Tohono O’odham and Apache) Indian assailants. The trial that followed resulted in the acquittal of all the accused. This singular but not unique event, known as the ‘Camp Grant massacre’, questions the eruption of violence in history. Under the title Shadows at Dawn: An Apache Massacre and the Violence of History, Karl Jacoby’s book of 2008Footnote 1 adopts a multiplicity of points of view in an attempt to understand this ‘violent storm’. It also examines the way in which events are remembered, suppressed, distorted and forgotten. Between genocide and survival strategies, this fascinating and painful story has been transformed – in the author’s own words – into a ‘palimpsest of many stories’, a polyphony of places, actors, contexts and pictures, a kaleidoscope of readings of a controversial past.

If we wish to pay attention to what happened, we can begin by listening to the murmur of names involved in the events: names of places, peoples, actors, all of which are meaningful and lively, evocative of landscapes, characters, attitudes and ways of being and acting, tracing names that echo the past, present and future. For instance, Askevanche is the name of an Apache chief which probably means ‘Furious, he thinks only of himself’; other Indians are called Chilitipagé, ‘Gone to war without permission’ and Gandazisłichíídń, ‘The one with red sleeve flaps’. As we suggest in the Introduction, these names tell stories that we can barely imagine. In the story of the carnage, we also come across the ‘People of the mountain top’, the Dziłghé; we stop ‘Where the great sycamore tree stands’, Gashdla’áchoh o’āā. The names speak at the same time of the landscape, the men, their temperament or behaviour, a physical trait or a clothing attribute, and of the territory and its inhabitants; they can also refer to ancestors or spirits/gods. A bit like pictograms that can only be understood in relation to each other, names weave links and signal relationships;Footnote 2 they constitute a language – that is, a system of signs that makes communication possible. Names are both snapshots that refer to a gesture, a word and an action as well as the receptacle of a long-term memory which situates a being, community or place in a wider whole that goes beyond it and encompasses it. A name is therefore not a simple ‘label’, but a vital principle, with the capacity to act on beings, things and the world; in other words, it is endowed with agency. A name marks persons or things that bear it; it describes and constructs, designates and shapes them. In speech acts, such as oaths or rituals that may involve the name in a binding way, the name creates effects: it links people, conveys knowledge, fixes norms or transgresses them, fosters a shared imaginary.

Names, whether given or adopted, also entail an external viewpoint – that of a person, group or place – and reflects their perception of it. This complexity may prompt the need or desire to describe and explain by creating an ‘aetiology’ that makes the relationship between the name and the person or thing that bears it explicit. Like the Greek ekphrasis, the literary procedure used to describe images, artefacts and representations,Footnote 3 names call for exegesis, give rise to narratives and activate networks of meanings. When it comes to understanding why a particular statue of a god has an apple, dove or turtle, a plethora of interpretations develop with divergent points of view coexisting. In the same way, the implicit meanings of names can convey a multitude of meanings that require clarification. What exactly is the meaning of the name ‘Human beings’ that the Apache have given themselves? Does it imply that the surrounding peoples belong to another ontological category, such as that of animals? And what experiences or imaginary does the name ‘People of the rope under their feet’, Kełtł’ah izláhé, which the Apache attributed to a group of O’odham, express?

The Iliad: Names to Mark out the Narrative

The mother of all ekphraseis (plural of ekphrasis), so to speak, is the long and magnificent presentation of Achilles’ shield in Book xviii of the Iliad (478–608). The poet describes an extraordinary object, a thauma – ‘wonder’ or ‘prodigy’ – endowed with intrinsic power because it was forged by Hephaestus at the request of Thetis, Achilles’ mother. On it are represented societies at peace and others at war, as in Troy where Achaeans and Trojans were tirelessly slaughtering each other. On closer inspection, the Iliad is also a tale of carnage without concessions; it is the ‘Poem of Force’, to use the expression of the philosopher Simone Weil, who devoted a very fine essay to it in 1940–1941 whilst the whole of Europe was under fire; the Iliad is the story of a massacre taking place not at Camp Grant on 30 April 1871, but at Troy in a distant, heroic and memorable past, full of values and countervalues.Footnote 4

Achilles, Achilleus, whose name is composed of achos ‘pain’ and laos, ‘people, army’, announces better than anyone the final disaster that the Iliad insinuates without actually describing it: the annihilation of the Trojans. We have to wait for the poem of the return journey (nostos in Greek), the Odyssey, to hear the story of the deceptive wooden horse, a ruse invented by Ulysses, the polytropos, the man of a thousand tricks, and to discover the echoes of the carnage of the Trojans that impacted men, women and children. The Iliad for its part ends in Book xxiv with the old king, Priam, sending an embassy to Achilles to beg for the return of the violated corpse of his son Hector to bury him.Footnote 5 As with the Indians, the Greek and Trojan chiefs have programmatic names that sound like omens – nomen omen, as one says in Latin: Patroclus is ‘Glory of the father’, Telemachus is ‘He who fights from afar’, Demodocus is ‘He who is welcomed by the people’, etc.Footnote 6 The names are like beacons that illuminate the narrative path; they seem to have the power of anticipation, while also reminding us of the strength of lineages and heritage. They are powerfully polysemous, like enigmas waiting to be unravelled. Starting with a few examples from the divine sphere, let us therefore examine how the names given to the gods contribute to the elaboration of a complex narrative in HomerFootnote 7 that sees them interacting with each other and with men in the context of a ferocious struggle for survival.

On the plain of Troy, after ten years of fruitless fighting, the scales were finally tipped in favour of the Achaeans. It is the gods who pull the strings. Their names can be simple or compound, intriguing, chiaroscuro and bouncing like an echo in a cave. Their complexity and that of their actions have challenged countless generations of listeners and readers. The meaning or meanings attached to the names of gods and heroes are not constrained but multiple, open and negotiable, and they are reassessed throughout the chain of interpretations that unfolds before us. Depending on his or her skills and perspective, a modern ‘exegete’ of the Homeric text sees one meaning emerging more than another, without it being possible or even desirable to fix a single and definitive meaning. The text breathes, and the large repertoire of names mobilised in the narrative provides oxygen for both poet and audience.

Let us start with Book i of the Iliad: the final confrontation was about to begin, provoked by the anger of Achilles, offended by Agamemnon, which was shaking up the military. On Olympus, the gods also mobilised, some for the Achaeans, others for the Trojans, but all subject, despite their personal strategies, to the ‘will of Zeus’ (the Dios boule, v.5), the fulfilment of which would inevitably determine the war’s outcome. The listener/reader knows that Achilles would be avenged, Troy destroyed and the Trojans annihilated, just as they know that Achilles would die and that the Greeks, Odysseus in particular, would struggle to arrive at their homes. But to reach this conclusion, hundreds – or, rather, thousands – of victims are required on both sides: women raped, children thrown from the ramparts and sanctuaries delivered to the flames, followed by the exile of the Trojan women whose enslavement Euripides would later recall.Footnote 8 This unprecedented display of violence, as in the Aravaipa Canyon, Hiroshima or the Sabra and Shatila massacre many centuries later, shakes our conscience. Focussing on the deities’ actions, it questions the notion of divine justice and the balance between good and evil, while from the perspective of mankind, it questions the legitimisation of the violence exercised by humans on humans: homo homini lupus.

In the Iliad, as a ‘Poem of Force’, but also of suffering, the effects of destructive violence are spread throughout the narrative. It is certainly in the bellicose exploits, the hand-to-hand combat with the enemy, that the individual strives to achieve kleos – that heroic ‘glory’ which reflects on one’s entire family and ensures the immortality of one’s ‘name’. But this exploit comes at a terrible cost, and for Homer’s listeners/readers it belongs to a glorious but bygone past. Patroclus, whose name means ‘the father’s kleos (glory)’, lives up to the reputation of his lineage, but he loses his life. Patroclus is mourned and celebrated with a grand funeral ceremony, combined with athletic competitions, but Achilles remains nonetheless inconsolable. The pursuit of glory and warrior excellence (aristeia) is central to the value system of Homeric society as the supreme ideal that justifies the use of violence. However, the Iliad, as Pascal Payen has shown, offers no case of an apology for unlimited violence.Footnote 9It is instead a long and disturbing examination of war as a dangerous and self-destructive social practice. Although there are many battle scenes, with approximately a third of the Iliad’s 15,688 hexameters devoted to confrontations between 360 characters involved in 140 duels, 230 of whom are wounded or killed,Footnote 10 the field of war is the object of a surgical and uncompromising observation; the military values are shown in an emphatically ambivalent light, to the point of appearing at times a danger for the future of societies. Does not Zeus say to Ares, his own son, the god of bellicose violence: ‘To me you are most hateful of all gods who hold Olympus. Forever quarrelling is dear to your heart, wars and battles’ (Iliad 5.890–891)?Footnote 11 The ‘reversals of war’ do not escape the poet: the dark side of heroism and the excess of violence that disarticulate societies, blur moral boundaries and lead to annihilation. Achilles himself – the embodiment of a kind of ‘extermination drive’, the best and the most odious (like Ares!), ‘the one whom nothing appeases’ and ‘whose fury has no end’, as illustrated by the outrage that he inflicts on Hector’s corpse day after day – ends up excluding himself from society. In Book ix (410–416), momentarily reassured by his mother’s words, he lucidly considers the two paths that any man can take:

I carry two sorts of destiny toward the day of my death. Either, if I stay here and fight beside the city of the Trojans, my return home is gone, but my glory shall be everlasting; but if I return home to the beloved land of my fathers, the excellence of my glory is gone, but there will be a long life left for me, and my end in death will not come to me quickly.

Achilles would choose the ‘imperishable glory’ that the Iliad’s poetic singer achieved perpetually, while reminding us that war, with its endless sufferings, lamentations and deaths, is also what distinguishes men from gods. In fact, the existence of the immortal inhabitants of Olympus is, by contrast, one of pleasure and joy. From afar, from above, the gods, who occasionally throw themselves into the skirmishes – something Zeus, the ultimate arbiter of the kosmos’ future, never does – observe the human ants tearing each other apart. Among the men, some almost managed to bridge the gap between the divine and the human, like Achilles, the best of the Achaeans, described as ‘like a god’, even ‘divine’, and whose mother, Thetis, was a nymph. Agamemnon, too, the leader of the expedition and king of kings, is described when he engages in battle ‘with eyes and head like Zeus who delights in thunder, like Ares for girth, and with the chest of Poseidon’ (Iliad 2.478–479). However, Achilles would die whilst Agamemnon was slain by his wife, Clytemnestra, on his return to Mycenae. The gods let the men kill each other while waiting for the final outcome. The poem is thus interrupted by scenes of assemblies of the gods on Olympus, during which they deliberated bitterly on what to do next.Footnote 12 Zeus, whose decisions are always resolute, not only allowed his companions to argue and struggle, including to injure themselves when they entered the conflict, but above all he allowed the plot to develop, branch out and go astray only to find itself again, thus maintaining the suspense for an audience who, conversely, already knows that at the end of the twenty-four songs Priam would finally bury Hector prior to the city of Troy being wiped out.

The Spectacle of War, Between Gods and Humans

For the gods, war was a spectacle that is both distressing and pleasing. Some engaged in it to the point of injury, like Ares being struck by Diomedes’ spear that also wounded Aphrodite (Iliad 5.855–861, 330–351), but most enjoyed the picture of men at war from afar: they were ‘rejoicing in the warriors; and the ranks of these sat close, bristling with shields and helms and spears’ (Iliad 7.61–62). Similarly, at the beginning of Book xx (23–24), Zeus says that, ‘sitting in a fold of Olympus’, he would be able to see the Trojans and Achaeans clash, a scene that ‘will make glad my heart’. The register of sight is crucial and strategic in the plot that unfolds, and then unravels, between the plain of Troy and the eternal abodes of the gods. The gods observed the humans who turned their gaze to the Immortals for help and support. Now, the names of the gods subtly bring into play their visual power and the worried gaze of men.

In an article entitled ‘Ce que les Hopi m’ont appris sur le paysage’ (What the Hopi taught me about landscape), Patrick Pérez highlights the role of the far-reaching view in the process of identifying, structuring and naming a landscape among the Hopi Indians of northern Arizona.Footnote 13 The first of the sensitive data that must be taken into account is ‘the fact of height, the domination of the gaze over the desert, the development of a wide and deep view that probes more than 150 km in winter, with a remarkable transparency of the air’.Footnote 14 It is a scene that the perceptual viewpoint constructs, a ‘microcosmic theatre’, a panoptic gaze that transpires in the toponyms and that is narrated, transmitted, memorised and updated through myth and ritual. In the Homeric poems, it is the gods who have a bird’s-eye view of the small world at war. From Olympus, from the summit of Mount Ida and the top of Gargaros, the gods looked down on both armies, while keeping an exceptionally close eye on the actions of their protégés. The gods’ view was at once superior, panoramic and precise, and the names that they were given provide a subtle and complex interplay of gazes: between the different gods, between gods and men, between the characters and the public who attend the performances. For the gaze is empathy and humanity, observation, analysis and judgement. Does not the one-eyed Cyclops belong to a ‘non-society’ where people do not come together to deliberate and where they do not care about others (Odyssey 9.112–115)?

Portrait of Euryopa Zeus, ‘Vast Voice’ and ‘Ample Sight’

Euryopa is a frequent name for Zeus, expressing the breadth of his gaze and voice; it is a polysemous qualification that constructs the representation of a god with extraordinary powers. His sensory performance, sight and voice are out of all proportion compared to what a human being is capable of. ‘Matters do not have the same appearance from far off as when seen close up’, says Ion in Euripides’ play of the same name, a family tragedy that revolves around the powers of Apollo who sees and knows what humans do not.Footnote 15 Apollo’s gaze, which surpasses that of men, is also endowed with an acuity that makes a difference. Paradoxically, the distance allows the gods to be more clairvoyant and efficient. This can be seen in a famous passage in the Odyssey (3.231) when Athena reminds Telemachus ‘Easily might a god who willed it bring a man safe home, even from afar.’Footnote 16 This ability to act from a distance presupposes a gaze that is both extensive and acute, similar to that of an eagle, the emblematic animal of Zeus, the ruler of the gods, whose designs are unfathomable and who orchestrates everyone’s fate from a distance. This is why the name Euryopa is associated with Zeus, and exclusively with him, no less than twenty-three times in Homeric poetry: sixteen times (including a duplicate) in the Iliad and seven times in the Odyssey.Footnote 17 Through this name, the poet underlines Zeus’s decisive role as arbitrator of the Trojan conflict; from the top of Olympus or Ida, he scrutinises events and, like a chess player, moves the pawns on the great and bloody chessboard of war. Nonetheless, his own son, Sarpedon, king of the Lycians and Priam’s faithful ally, dies in battle, despite the pity his fate inspires in Zeus (Iliad 16.431–461). In celebrating the exceptional abilities of the ‘father of men and gods’, the expression Euryopa Zeus, always in this order, often for metrical reasons at the end of the verse, is only once, in the Odyssey,Footnote 18 extended into Olympios Euryopa Zeus, which specifies Zeus’s topographical location, enthroned at the top of Olympus, in a dominant position like an eagle on the highest peak of a mountain.

But what exactly does Euryopa mean? Its etymology points to both the visual and auditory spheres since the term is formed from the Greek noun ops, which means ‘voice’ and ‘eye’, ‘sight/vision’. This term is found in the famous onomastic sequence Athena Glaukopis (‘with blue eyes’) and in Hera Boopis (‘with the eyes of a heifer’), two names to which we shall return.Footnote 19 The adjective eurys means ‘large’, ‘ample’. Euryopa can thus be translated as ‘with a large voice’ and ‘with a vast gaze’. The term’s polysemy is constitutive of the representation of Zeus’s sovereign powers: the large sounds he emits, notably the rumble of thunder, fills the world with divine resonance, while the fullness of his gaze means that nothing escapes him. The first mention of Euryopa Zeus in Book i of the Iliad (498) is quite revealing of the narrative and the figurative potential of this name. Achilles, offended by the fact that Agamemnon has taken from him Briseis, the Trojan captive who belonged to him as his share of the booty, lets his anger explode, the anger that the Muse is invited to sing from the very first lines of the poem: a ruinous anger that brought infinite suffering to the Achaeans and sent the souls of powerful heroes to Hades, their bodies being delivered to dogs and birds (Iliad 1.1–5). The picture is grim from the start. Achilles, ‘the best of the Achaeans’, humiliated, retires to his tent and cries in the arms of his mother, the nymph Thetis. She then decides to go to Olympus to beg Zeus to save her son’s honour by giving victory to the Trojans until the Achaeans open their eyes to the wrong suffered by Achilles and restore his rank and honour. The scene of the meeting between Zeus and Thetis on Olympus is crucial to the development of the plot: “She found Kronos’ broad-browed (euryopa) son apart from the others sitting upon the highest peak of rugged Olympus” (Iliad 1.497–499). The poet chose the name Euryopa, son of Kronos to emphasise the high stakes of this face-off. The son of Kronos, Zeus, sits apart, higher up, in a dominant position, as is his will (in Greek, boule), which Thetis strives to bend in favour of her son. Euryopa, ‘powerful voice’ and ‘wide-eyed’, simultaneously qualifies – like the names of the Indian chiefs mentioned earlier – the decisive force of Zeus’s sentences and the breadth of his gaze that embraces all the actors in the drama, all the places and all the resources. However, when Thetis seeks a word of consent from Zeus – whom she addresses by calling him ‘Father Zeus’, another way of emphasising his authority whilst trying to soften him up – she receives a sign with his eyebrow.Footnote 20 As supplicant, Thetis kneels and holds the god’s knees; Zeus, described as ‘Assembler of the clouds’, another name indicating the extent of his powers, confides in her his fear of the reaction of Hera, his wife and ‘intimate enemy’,Footnote 21 before showing his favourable decision with a movement of his eyebrow and his hair that makes the enormous mass of Olympus tremble.

It is true that Zeus has a ‘human’ body, like all of Homer’s gods. He is depicted in an anthropomorphic pattern, but, on closer inspection, everything about the way he is and acts differentiates him from humans.Footnote 22 Anthropomorphism is nothing more than a narrative strategy, a language that provides the poet with emotional and relational resources and tools, but it in no way means that the Greek gods were conceived of as being ‘human’.

In 1811, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres produced an extraordinary portrait of Euryopa Zeus in the famous canvas Jupiter and Thetis, now in the Musée Granet in Aix-en-Provence (Figure 1.1). Here, the asymmetrical communication between the two figures involves an incredible interplay of glances: below, the pleading Thetis, her gaze imploring, turns to Zeus who sits above, majestically on his throne, his eyes riveted on the horizon in the distance. Next to Zeus’s throne, an eagle seems to have lent the god its piercing, sharp and intense gaze. In Book ii of the Odyssey (146–147), while Antinoos, the leader of the contenders who had discovered Penelope’s ruse, threatened to stay as long as she did not choose a new husband, Telemachus appealed to the immortal gods and to Zeus’s justice and ‘Zeus, whose voice is borne afar [Euryopa], sent forth two eagles, flying from on high, from a mountain peak.’ Halitherses, the soothsayer of Ithaca, easily interpreted this fatal sign for the contenders: Ulysses was on his way and would take revenge on them. The modus operandi of the eagle and that of Zeus become conflated: from a great height and a great distance, they see and act quickly and strongly. In the scene of Thetis’ supplication, Zeus is not so much insensitive to the imploring gaze of his interlocutor as ‘visionary’. With his vast and luminous gaze, he fixes the destiny of each person and ensures the functioning of the kosmos by making definitive judgements. His voice, in the sense of ‘decision’, and his gaze, in the sense of ‘vision’, complement each other to paint the portrait of an eminent, superior, omnipotent god.

Figure 1.1 Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Jupiter and Thetis (1811)

The poet – and this is his art – subsequently plays with the wealth of meanings conveyed by the name Euryopa Zeus, directing the spotlight sometimes in one direction, sometimes in the other, so that the listener or reader, by successive insinuations, enriches their understanding of the god designated by this name. Thus, the ‘visionary’ Zeus who is master of the course of events, the one who fixes and controls the future of the world and of men, is again brought to the stage in Book xiii (730–733), when Polydamas, a Trojan chief, discusses with Hector the distribution of qualities among men:

Managing each person’s destiny, we see the Moirai intervene at the end of Eumenides, Aeschylus’ tragedy that closes the cycle devoted to Orestes, the parricide pursued by the Erinyes. Goddesses responsible for the moira, the ‘part’ that falls to each mortal, the Moirai are called Panoptas, ‘who see everything’, as guarantors of the universal order established by Zeus (1045–1046). This panoptic gaze of Zeus, an expression of his power, is also a source of justice and fairness, two values that Thetis claimed for herself when she interceded on behalf of her humiliated son. This is why Hera recommended to Apollo and Iris, who join Zeus Euryopa, seated at the highest peak of Mount Ida, Gargaros, with ‘fragrant cloud gathered in a circle about him’ (Iliad 15.153): ‘when you … looked upon Zeus’ countenance, then you must do whatever he urges you, and his orders’ (Iliad 15.147–148).

In other passages, the poet emphasises the impact of his decisions; Euryopa Zeus’s large and powerful voice takes precedence over his gaze, as in a passage in Book iii of the Odyssey: Nestor, the wise old king of Pylos, told Telemachus, who had gone in search of his father Odysseus, about the difficulties of his own return from Troy in the company of Menelaus. After a stop near Cape Sounion, where he had to bury his pilot struck by Apollo’s arrows, Nestor set sail again and arrived under the cliffs of Cape Maleas, not far from his final destination; ‘then verily Zeus, whose voice is borne afar [Euryopa], planned for him a hateful path and poured upon him the blasts of shrill winds’ (288–290). The power of the sea, unleashed by Zeus, eventually caused them to drift to Crete, delaying their return home. The whistling of the evil winds and the crashing of the swell refer here to the sound register of Euryopa. Similarly, in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, Euryopa Zeus is referred to as baryktypos, ‘with a deep roar’.Footnote 23 In verse 3 of this hymn, the poet sings of Demeter and her daughter ‘given to him [Hades] by all-seeing [Euryopa] Zeus the loud-thunderer’. When he rumbles from the heights or the depths of the kosmos, Zeus makes his voice heard as a final decision. Deep or wide, both the vision and the voice of Zeus ensure effective communication without appeal.

Networked Names: To See, Monitor, Protect and Judge

The Ancients, who learned Homer at school and made the Iliad and the Odyssey the basis of their education (paideia in Greek), wondered about their meaning or meanings despite being familiar with the innumerable names that ‘colour’ the gods and highlight facets of their multiple personalities. The whole stock of poetic, refined, rare and often compound terms, such as euryopa, baryktypos, glaukopis and boopis, that Homer coined to describe the multiplicity of divine powers and that many authors after him recycled, have fed a scholarly reflection that has spanned the centuries. Homer’s scholiasts who flourished from the Hellenistic period onwards and were still very active in the Byzantine period, as well as the authors of dictionaries, lexicons and other encyclopaedias, explored the possible meanings of these often polyvalent qualifications, as we have seen for euryopa. The attempt to fix ‘the true meaning’ is doomed to failure as it is clear that the poet played with the ambivalence of the names and their elements. Euryopa Zeus is no more truthfully ‘wide-voiced’ than ‘wide-eyed’: he is both because the divine possesses sensory properties – in this case, voice and sight – that are superior and different from those of humans.

Some ancient authors, just as we suggested, also did not make a decision. The Byzantine dictionary called the Suda (E 3726) cautiously advances: ‘(Meaning) large-eyed, or large-voiced. The nominative (is) euryôps.’ The link between the amplitude of the gaze and voice and the ability to survey the kosmos is also retained by the first-century ce grammarian Apollonius the Sophist in his Lexicon Homericum (79.19–21, ed. H. Ebeling): ‘Euryopa: epithet of Zeus, either by reference to the fact that he watches amply [ephorônta], or to the fact that he produces powerful sounds and noises, or because of his great eye.’ Zeus is thus the great ephor of the world, a term which in Sparta refers to the five magistrates who governed and oversaw the population as much as the two hereditary kings. Homer was the first to make Zeus the ‘overseer’ of the world, a function that Demosthenes later attributed to Dike,Footnote 24 proof that ‘watching and punishing’ already went together. Helios, the Sun, by virtue of his daily course through the heavens, is also the witness of all things, thus a god of justice, described as ephor, for example, in Book iii of the Iliad (276–279). There Agamemnon addresses a solemn prayer to the gods to seal the pact that is supposed to unite Achaeans and Trojans in an attempt to reach a truce and solve the conflict by a single combat between Paris and Menelaus. He first turns to ‘Father Zeus, watching over us from Ida, most high, most honoured’, and then to ‘Helios, you who see all things, who listen to all things’. Sharing an overarching position, Zeus and Helios see, hear, watch and rule everything. Zeus, however, is the only one who is ‘most glorious’ and ‘most high’.

For an ancient reader, Euryopa thus resonates with other words and deities, belonging to similar registers. The term ops, ‘voice’ and ‘sight’, enters into composition with various adjectives and substantives, such as panoptas/panoptes that we encountered in Aeschylus’ Eumenides to emphasise the capacity of the Moirai and Zeus to see and know everything.Footnote 25 Similarly, in Sophocles’ Oedipus at Colonus, a tragedy whose plot revolves around Oedipus who is now blind after discovering the truth about his existence, the hero is confronted with a destiny that is completely beyond his control as he thought he was omniscient since he had been able to answer the riddle of the sphinx; in verses 1080–1086, the chorus of Athenian elders, having just announced to Oedipus Theseus’ victory over Creon, the king of Thebes who drove out Oedipus, and the return of his own people to Thebes thanks to Zeus’s action, cry out: ‘Oh, to be a dove with the strength and swiftness of a whirlwind, that I might reach an airy cloud, and hang my gaze above the fight! Hear, all-ruling lord of the gods, all-seeing Zeus! Grant to the guardians of this land to achieve with triumphant might the capture that gives the prize into their hands!’Footnote 26 The text subtly plays on the opposition between Oedipus, plunged into darkness, and Zeus, who governs all the gods (pantarche theon) and who sees everything (panopt’) above the clouds, like a dove this time, bringing good news. As for the adjective eurys, ‘wide, large’, which forms part of Euryopa, it occurs in various other divine qualifiers: Euryanax, ‘vast prince’, is used for Zeus, as well as Euryanassa, ‘vast princess’, for Demeter; Eurybatos, ‘with vast stride’, again for Zeus; Eurybias, ‘with vast strength’, for Poseidon, and so on. Ampleness and amplitude are typically divine qualities that denote physical, sensory and cognitive dispositions superior to those of men. In this respect, both eury- and pan- function as intensifying superlatives.

In addition to this interplay between words that creates echoes from one god to another, from one text to another, from one context to another, we must also mention scholarly prowess based on Homeric reminiscences. Some authors had fun updating Euryopa Zeus in contexts that are out of context in order to display their high cultural level and increase their prestige; this is the case of Dioscorus of Aphrodito, an Egyptian dignitary and author of a eulogy dating to around 551 ce in Constantinople, which is addressed to a certain Hypatios, a senior civil servant attached to the praetorian prefect.Footnote 27 He sketched a comparison between the eulogy’s addressee and nothing less than Zeus: ‘If Euryopa Zeus carried the consular leadership in the capital, you could bear your name.’ Dioscorus played on the name Hypatios, which he linked to the term hypatos, ‘elevated’, and on Zeus’s designation Euryopa. Echoing Homer, he flattered Hypatios by describing him as a god of the peaks and by offering him a model of social ascension.

Athena ‘Sharp Eye’ and Hera ‘Heifer’s Eye’

Considering the gaze as an attribute of power, what exactly do the names Glaukopis, ‘Owl/gleaming-eyed’, and Boopis, ‘Heifer-eyed’, signify for Athena and Hera respectively? If Mona Lisa’s gaze fascinates people several hundred years after Leonardo da Vinci fixed it on canvas, what effect could Hera’s heifer gaze and Athena’s ‘glaucous’ gaze possibly have? At first glance, these designations may leave a modern reader perplexed. We must therefore look for the ancient codes to decipher them.

In his Lexicon Homericum (52.9–10), Apollonius the Sophist explains Boopis as megalophthalmos, ‘great eye’, or megalos ephorosa, ‘greatly watching’, adding a suggestive comment: ‘for Zeus, too, is called Euryopa’. The association of Boopis with Euryopa provides an interesting reading. Hera, and her alone among all the goddesses,Footnote 28 is called Boopis as early as Homer; some scholiasts interpreted this as a trait of beauty, perhaps similar to us today saying of someone that she has ‘doe eyes’. This connotation should not be excluded,Footnote 29 but Apollonius suggests a functional connection between Zeus and Hera, the couple of sovereign gods, who would share the property of having a wide view of the world to manage and protect it.Footnote 30 The large eyes also have an apotropaic value: that of repelling the ‘evil eye’. This is why Greek potters decorated certain vases with a pair of gigantic eyes that protected the owner of the object, just as large eyes were painted on the prow of ships to guard against the dangers of the sea.Footnote 31

As for Athena, the Virgin par excellence, born from the brain of her father Zeus, she is frequently called Glaukopis, a name rich in symbolic resonance.Footnote 32 Almost exclusive to Athena,Footnote 33 it refers on the one hand to the piercing and vigilant gaze (glaux) of an owl, the goddess’s symbolic animal, just like the eagle for Zeus; on the other hand, it refers to the colour glaukos used to designate a wide range of blue, green or grey tones, ‘which share a certain form of clarity and luminosity’.Footnote 34 The verb derived from the adjective glaukos is applied to wild beasts that fix their prey before attacking it. Athena Glaukopis therefore designates a goddess with a vigilant and frightening gaze, fascinating and disturbing, dynamic and savage, which speaks of her power, her ardour and her capacity to act for or against humans. Sharp and penetrating, this gaze characterises her so well that in Sparta she was called Athena Ophthalmitis, ‘of the eye’.Footnote 35 Her tree, the olive tree, is also glaukos, luminous and indomitable, sparkling and changing, and therefore combative.Footnote 36 A champion in metis, a form of cunning intelligence, Athena adopts a very large number of appearances: ‘Hard is it, goddess, for a mortal man to know thee when he meets thee, how wise soever he be, for thou takest what shape thou wilt’, Ulysses tells her (Odyssey 13.312–313).Footnote 37

Gustav Klimt expressed the power and fascination of Athena Glaukopis’ gaze remarkably well in his painting Pallas Athena of 1898. He shows her in a frontal position, wearing a golden helmet that encircles her face and allows only her red hair to show through.Footnote 38 The goddess’s hypnotic gaze captures the viewer’s attention; its fixity, limpidity and intensity are well matched by the brilliance of the gold that protects and makes her body glow. Klimt has chosen to break away from the academic style by giving the goddess a fearsome and active power. Her tetanising gaze is echoed in the Gorgon she wears on her aegis-covered chest, a figure whose sight literally petrified the beholder. The portrait of the goddess is a striking illustration of her name: Pallas, the Fierce Virgin, the title chosen by Klimt for his work, but it also refers to Glaukopis, she whose gaze fascinates, protects and frightens.

Burying the Dead and Fulfilling Your Destiny

Let us return briefly to the Aravaipa Canyon on the 30th of April 1871 with Karl Jacoby as our guide. In the midst of lush vegetation, on the banks of the stream that the Apache occupied, all was quiet on this spring night. Suddenly, death burst in: one group of attackers on horseback, others on foot. Within a few moments, hundreds of corpses litter the ground; the massacre was accomplished without a single hand or conscience shaking. In December of the same year, the trial of the murderers began that resulted in a general acquittal. In the spring of 1872, a year after the events, a peace conference was organised to help the different communities involved find a way to reconciliation. The Camp Grant massacre was destined to enter the realm of memory: memory and oblivion. No one knows what happened to the bodies of the Apache caught in their sleep. Were they ‘given over to dogs and birds’, as the poet bluntly puts it at the beginning of the Iliad (1.1–5)?Footnote 39

On the plain of Troy, as the war was drawing to a close, the story concludes around the fate of Hector’s corpse. The gods were invoked to accompany what is only a temporary reconciliation. Great governors of human destiny, the gods, though largely elusive, have names that humans gave them in order to interact with them. Approximations and conjectures, these human names for the gods will again be our common thread in the footsteps of Priam. In the last book of the Iliad (Book xxiv) several gods are involved in the perilous embassy that would lead Priam to Achilles. The stakes are high: recovering Hector’s body in order to bury him with dignity; the risk is great: exposing oneself to Achilles’ murderous rage. It is a humanitarian mission, so to speak, that the gods favour so that the positive values of living together would momentarily take over among both Greeks and Trojans. Achilles, if he grants the old king’s request, will at last be able to renounce his unquenchable fury; Priam, if he succeeds in moving the heart of the Greek, will finally be able to honour his dead son according to the prescribed rites. Order will return to earth before the tragic end. The climax of the story, Book xxiv, tells of the calm before the storm. With Hector buried, the Greeks, inspired by Ulysses, will stage their departure and leave the wooden horse, filled with soldiers, on Troy’s shore, which the Trojans will bring into their walls to offer it to Athena in her temple on the acropolis. It is then that violence will be unleashed in accordance with Zeus’s boule, with Achilles regaining his honour, Troy disappearing and Achilles dying.

But the poet does not describe these moments of fire; he merely alludes to them. He concludes the Iliad with the splendid Book xxiv, which opens with Priam despairing to see, day after day, Achilles abusing the corpse of Hector by tying it to his chariot and dragging it around the walls of Troy. Achilles has lost his humanity and the gods are finally moved by this tragedy. The story is at an impasse and an assembly of the gods intervenes to unravel the threads of the narrative. In 804 beautiful verses, the poet then stages Hector’s redemption (in Greek, the lutra or ‘ransom’) through a series of narrative sequences of great intensity. According to our hypothesis, the names of the gods mark out the narrative and make the issues more explicit.

Achilles is weeping: this is the first scene. Patroclus’ funeral is over, but his grief does not leave him. His torment nags at him; he finds no other vain escape than the daily outrage inflicted on Hector’s body. Apollo, however, one of the Troy-friendly gods, safeguards the hero’s remains by means of the aegis, a talisman with apotropaic powers;Footnote 40 Hector’s body stays intact day after day. While both sides are suffering ravages, the ‘happy gods’ – such a designation in this instance accentuates the chasm between the divine and human spheres – are considering entrusting a mission to Euskopos Argeiphontes. We recognise Hermes under his common designation ‘Slayer of Argos’ (Argeiphontes) that refers to the hundred-eyed giant Argos, himself called panoptes, ‘all-seeing’, protector of Io, Hera’s priestess in Argos, whom Hermes had eliminated at the behest of Zeus.Footnote 41 Charging Hermes ‘Good View’ (Euskopos) with the care of Hector’s corpse also activated the psychopomp function of the god who accompanies the dead to the afterlife. However, Poseidon, Hera and Athena, the most ardent defenders of the Achaeans, are against this mission. After twelve days of waiting, Phoibos Apollo, a name that describes the god as luminous and sparkling, but also terrible and fearsome, returns to the Council of Gods.Footnote 42 Achilles, he argues, has lost his sense of pity and shame, two feelings that for men constitute a constraint as well as a benefit. The gods’ nemesis, their moral sanction, is imminent. Leukolenos Hera, the goddess ‘White Arms’,Footnote 43 a typically feminine qualification, shared with mortals such as Helen, Andromache and Nausicaa, takes offence at the prospect of equal honours being bestowed on Hector and Achilles, the latter alone being of divine descent through his mother. It is finally Zeus, ‘Assembler of the Clouds’, who decides the matter, as is right and proper. Hector never skimped on offerings to the gods, especially to Zeus, whose altar was always full. He is therefore legitimately entitled to the funeral honours, but the outcome should not be forced. By sending Iris, his messenger whose name refers to the rainbow, the sign of the gods,Footnote 44 to fetch Thetis, Achilles’ mother, Zeus favours the diplomatic route. ‘Fast as a storm’, Iris, also known as ‘swift-footed’ to evoke the way she carries out her mission, conveys to Thetis the will of Zeus ‘Infallible thoughts’: she has to visit him to receive his orders. The way in which Zeus is referred to signals a turning point in the plot: Achilles must give in and his mother has to notify him. In her reply, moreover, the divine ‘Silverfoot’ Thetis calls Zeus Megas Theos, ‘Great God’, as a sign of submission and loyalty. As in the supplication scene we analysed earlier,Footnote 45 it is again Euryopa Zeus who receives her, the god whose ample voice and panoramic gaze fixes the fates. This time, however, he is surrounded by ‘all the blessed gods who live forever’, a solemn title for a serious moment. Thetis is greeted with honours: Athena gives her place at Zeus’s side to her, while Hera offers her a drink in a golden cup. The nymph is charged by Zeus to convey to his son the indignation of the gods and their desire to see him return Hector’s body to his family. Zeus will convince Priam to go to Achilles’ tent with gifts.

Thetis complies and manages to bend Achilles’ hardened heart. The supreme authority of Zeus the Olympian could no longer be challenged; he is the ‘strongest’ of all the gods (Iliad 1.580). The names attributed to each character function as codes and signals that weave an underlying network of representations and meanings. The two passages describing Thetis’ visit to Zeus, in the first and last songs, resonate with each other, while the names, like beacons, alert the listener/reader to the interplay of echoes and reminiscences. Zeus then takes in hand, with the help of Iris, the organisation of the embassy of Priam ‘the magnanimous’. To reassure the old king, Zeus sends him Hermes Argeiphontes ‘Good View’; in these circumstances, a hundred eyes are better than two because the expedition is very perilous.

Meanwhile, Priam, still crushed with grief, wrapped in his cloak, his head and neck covered with litter as a sign of mourning, is slumped on the ground. Everywhere, painful lamentations resound. But Iris encourages Priam to follow Zeus’s invitation. With courage and determination, the old king chooses precious tributes for Achilles, while consulting with his wife Hecuba, who considers the undertaking foolish. ‘Godlike’, a qualification that speaks of his strength and resolve, Priam does not give in. As the chariot is ready to leave, Hecuba recommends that her husband makes libations to Zeus, to address his prayers to the ‘Son of Kronos Assembler of the clouds’ and ‘Lord of Ida who watches over all Troy’. The names chosen to invoke Zeus’s protection point in two directions: on the one hand, the supreme master of Olympus, the son of Kronos, whose powers in heaven and on earth are (re)known to all; on the other hand, the lord of the mountain overlooking Troy, Ida, is mobilised, the god of the land who watches over Troy’s people and territory. The articulation between these two facets of Zeus – one Panhellenic, the other local – is particularly clear in this context; the impending danger implies that no resource should be neglected.Footnote 46 Hecuba advises Priam to ask Zeus for a sign of his favour, the sending of a bird that Priam will see and that will see Priam, accompanying him to Achilles’ camp. Hecuba asks Euryopa Zeus to grant her husband this favour; she invokes the god of the peaks, the god with the piercing gaze of an eagle, the god-ephor who watches over men. Priam then complies by stretching out his arms to Zeus, whom he calls ‘Zeus father who rules/watches from Ida, most glorious, most great’, a god whom Agamemnon, the king of the Greeks, had also invoked in Book iii of the Iliad.Footnote 47 In these equally solemn circumstances, Greeks and Trojans used the same onomastic sequence, a sign, here too, of a network of connivances subtly woven by the poet. These names, adapted to the context, honour and delight the gods. In this case, Zeus Metieta, the ‘Subtle’, the god of metis, hears Priam’s plea and immediately sends him an eagle, ‘the most auspicious of all birds’.

The chariot leaves Troy, driven by Idaeus, the coachman, whose name also refers to the local Mount Ida. Euryopa Zeus follows the two brave Trojans with his eyes as they are moving across the plain; taken with pity for old Priam, he sends him Hermes, ‘his dear son’, an interesting and rare qualification that indicates that Zeus’s empathy for Priam is that of a father driven by love; Hermes is to Zeus what Hector is to Priam, despite the context of a world unstructured by the outrages of war. Hermes’ mission is to ensure that the Achaeans neither see nor recognise the two Trojans before they reach Achilles’ tent. Hermes is a reliable guide; he is also an expert in hiding and lying, the god of thieves as well as travellers. The text qualifies him as Diaktoros, ‘Companion’. Equipped with the golden sandals with which he flies over land and sea, Hermes also carries a staff with which he bewitches the eyes of men or awakens those who are asleep. To guide Priam, he takes on the appearance of a young prince; he made himself Eriounios, ‘Benefactor’, echoing Zeus’s benevolence towards the Trojan ruler. The latter addresses the young man by calling him ‘dear child’ (373). The narrative gradually brings back the lost values of humanity swallowed up by the war. Having reached the Achaean camp, the travellers benefit from the powers of the one whose gaze is effective: Hermes spreads sleep over the eyes of the Greeks and leads Priam to Achilles’ tent. The denouement is near; the tension is at its height.

Hermes then reveals to Priam his identity as an ‘immortal god’ (460) and the nature of his mission, commissioned by Zeus; from now on, it is up to him. With Hermes having returned to the heights of Olympus, Achilles ‘dear to Zeus’ and Priam ‘the great’, ‘with divine allure’, face each other. The old king, in supplication, embrace Achilles’ knees – as, at the beginning of the poem, Achilles’ mother had embraced Zeus’s – and kisses his homicidal hands that deprived him of so many sons (Figure 1.2). The emotional intensity of this sequence is exceptional. The gods have withdrawn, but are watching; to men, there is still pain to be shared. ‘Remember your father’, Priam says to Achilles ‘like the gods’ (486). Face to face, ‘in the name of the father’, they mingle their tears and memories, softened by the shared emotion of a humanity which, although ‘like the gods’, is not given a happy eternity as a prize but suffering, death and compassion (525–526). ‘There are two urns’, says Achilles, ‘that stand on the door-still of Zeus. They are unlike for the gifts they bestow: an urn of evils, an urn of blessings’ (527–528). The fate of men oscillates between these two poles. Similarly, Achilles’ attitude towards Priam mixes gentleness and irritation, even threat, while Priam shifts several times from hope to fear. Finally, on Achilles’ orders, Hector’s body is washed, then placed in a coffin which is put on the chariot bound for Troy after Achilles and Priam have shared a meal. Soothed by food and drink, the two protagonists enjoy the sight of each other: Achilles is tall and handsome, like the gods; Priam is noble and wise. For the humans, as for the gods, the interplay of looks expresses emotions and mutual recognition. A twelve-day truce, which Achilles promises to keep, will allow the Trojans to bury Hector and pay homage to him. Afterwards, the battle will resume. This time Achilles stops the war not to give vent to his anger, but to show his humanity.

Figure 1.2 Priam pleading with Achilles. Onyx cameo (1815–1825)

The truce, as we know from the start, will be temporary. The gentleness that characterises this last song announces, paradoxically, the final violence. Andromache, Hector’s widow, alludes to Priam’s return as if to warn the listener/reader. Her son will not reach his prime, she announces, for the city will be destroyed long before that; for male and female Trojans, she continues, a fate of servitude, exile or death is inevitable. The performance of the funeral rites for Hector thus sounds like the harbinger of far greater disasters. As Hector is placed in a golden coffin, wrapped in a purple shroud, and a mound is raised over his grave, eyes turn to the shore from where the Achaeans are feared to attack. But the poet himself seems to look away as the dreadful fate of Troy is fulfilled.

Throughout Book xxiv, as in the poem as a whole, the names attributed to gods and men are neither mere ornaments nor pure fossils of an oral and formulaic past. Of course, they are also that, but they contribute above all to weaving the narrative’s complex construction, the poikilia made of relations between gods, relations between men, relations between these two spheres, relations between the past and the present, between the multiple narrative sequences that organise the ensemble into a vibrant whole with a thousand resonances. The names also draw up portraits in action that connect various functions, multiple appearances and innumerable modes of intervention, sumptuously highlighting the complexity of the divine nature. While knowledge of the gods is and will always remain imperfect, hypothetical and approximate, naming them means to create the conditions for an interaction that one hopes will be favourable, even in the most appalling trials.