1 Introduction: Gender and Literary Geography

The difference between men’s and women’s relationships with public space has long shaped literature, scholarship, and social life. It has structured narrative plots and character development and has been integral in the development of feminist theory, gender studies, and critical race theory. Contemporary social movements – from #MeToo to Black Lives Matter to Occupy – attest to the continuing, urgent relevance of physical space to cultural identities. Literary and cultural critics have sought to understand how social rules that structure the gendered occupation of space and the ability to travel, whether around the world or through a neighborhood, impact life and its representation. Yet little is known about how gender and representations of space interact at broad scale, across centuries and in many thousands of books.

Previous studies of gender and literary geography were restricted, by necessity, to individual books or small groups of texts.Footnote 1 That work has enriched immeasurably our understanding of the relationship between gender, space, and narrative (usually within a single literary era). But it lacks the scope to identify persistent patterns or to investigate the veracity of “common knowledge” narratives about literary geography that are widely shared, if often unstated.

The predominant but under-supported critical story is as follows: in literature as in life, nineteenth- and early twentieth-century men had greater freedom of movement than did women. Men enjoyed greater access to urban environments, foreign locales, and public spaces, while women were more often confined to the home. Some gains in women’s mobility were made in the early years of the twentieth century, but significant change did not come about until World War II, when women took up jobs left vacant by enlisted men. Aside from a conservative reaction in the 1950s, women’s mobility thereafter increased until, in the late twentieth century, it approached that of men.

The details of this sketch are debated, but, despite a paucity of evidence, its broad outlines remain unchallenged, even unquestioned. This story has had important effects, not only on the history of gender, but on such core concepts as “the city” and “nature.” From its early days, metropolitan space, with its connotations of modernity, has been regarded as masculine, leading some to conclude that “The literature of modernity describes the experience of men. It is essentially a literature about transformations in the public world … of work, politics and city life” from which women were excluded or “practically invisible.”Footnote 2 Nature, on the other hand, bolstered by ancient conceptions of motherhood and fertility, has more often been represented as the preserve of the feminine.Footnote 3

By examining the relationship between gender and geography in over 20,000 volumes of fiction published in Britain between 1800 and 2009, including special focus on the long modernist era near the middle of that period, we offer corrections to widespread assumptions about the role of gender in the geographic imagination. We identify how literary geography has changed – and remained consistent – over time and provide vital contexts for enriching our understanding of individual works of fiction. We also strive to detail how choices we made in the course of our research helped to shape our findings. As our discussion will emphasize, data collection and analysis are inevitably intertwined with human decision-making.

The remainder of this section surveys gender and literary geography in traditional literary studies, identifies the strengths and limits of quantitative methods in the field, and introduces the parameters of our investigation, including how our choices at the outset have shaped our research results.

1.1 Gender and Geography in Literary Studies: An Overview

Feminist literary criticism has always been alert to the significance of space in the construction of gender roles. As Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own (1929) famously argued, the spatial expression of gender roles has many implications for what and how literature was produced. Women’s opportunities to become writers were – and perhaps still are – limited in two spatially constructed ways: women rarely enjoyed private space (the “room of one’s own” necessary for sustained creative work), and they were denied access to particular places, from universities to certain parts of the city to foreign locations, that were foundational to male writers’ development. While Woolf and her likeminded contemporaries saw unequal opportunities for men and women stretching back across centuries, it was to the Victorian era that they turned to explain the entrenchment of gender roles around spatial divisions. The ideology of separate spheres meant that men were duty-bound to brave the rough world of the public sphere, while women were obliged to create a sanctuary in the private home. As “the Angel in the House,” to use the title of Coventry Patmore’s hugely popular poem (first published in 1854), a proper (middle-class) woman would inhabit and produce domestic space, venturing alone into public spaces only to shop for her family or to conduct charitable visits to the homes of the poor.

However unevenly available and enforced separate sphere ideology was in practice, even after the end of Victoria’s reign, it continued to delimit women’s lives, as Woolf and others argued. Decades later, best-selling works of second-wave feminism such as Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963) testified to its persistence. Literary scholars, from the 1970s onward, have explored how literature inculcated and policed gendered spatial divisions and how, alternatively, literature could help readers to imagine subverting those divisions.Footnote 4 The past generation of feminist literary scholarship has deepened its engagement with the spatial aspects of gender, examining not only how gender roles have been expressed, policed, and resisted spatially but also how the crucial roles of race, class, nationality, sexuality, age, ability, and other categories of identity intersect with gender in spatial organization.Footnote 5

A key marker of social position is the availability and circumstances of travel. While people have always left (or been forced from) their homes to find new ones elsewhere – for work, for food, for a better life – the voluntary, temporary leaving of one’s home is relatively new in human history and, until quite recently, one had to be very rich to afford it. It also helped if one were a man. The tradition of the Grand Tour arose in the seventeenth century as a necessary part of a wealthy young man’s education, preparing him for his station as a political and social leader. Sending women abroad was generally regarded as a waste of money until the late nineteenth century, when finishing schools sprang up on the Continent to teach the daughters of elite families the skills that would help them secure a suitable husband. The nineteenth century in fact saw increasing numbers of women traveling abroad – for religious purposes, as the wives of colonial civil servants, and for education and pleasure – but they remained in the minority among travelers.Footnote 6 No wonder, then, that when women voyaged to more exotic lands, or traveled without chaperonage, they often seized the public’s imagination. Florence Nightingale, Mary Kingsley, Gertrude Bell, the anthropologist Margaret Mead, and, earlier, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu were remarkable women travelers whose glamor derived in no small part from how very unusual they were. In the postwar era, the iconic woman traveler was a stewardess, whose mobility was largely confined to the airplane and its supporting spaces, the airport and the hotel. Even now, when international travel for wealthy Western women is a sign of their success, independent travel by women remains often a subject of special concern, as evinced by the near-obligatory “for the solo woman traveler” section in guidebooks and travel sites.

An area of intense scholarly interest has been the role of gender in two phenomena that are often conflated: the urban environment and modernity. In Britain, Europe, and North America, the great migration to cities initiated by the Industrial Revolution created a new way of life. In place of lives spent surrounded by familiar people, in landscapes known by their forbearers, large numbers of people experienced the shock of urban estrangement. The relative anonymity of the city and the dominance of industrial capitalism, with its timetables and quotas, made “modern life” distinct. Technological and cultural innovations from the telephone to the department store – and the changes in social relations they helped to bring about – generally reached cities first and in greater numbers. Travelers from foreign lands came first to cities, too, reinforcing the association of metropolitan life with global currents of trade, politics, and culture.Footnote 7

Early scholarship on modernity and modernism largely neglected women’s participation in the modern city.Footnote 8 Its literature, as it was constructed by literary critics of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, largely celebrated the experience of the flâneur, the privileged man who walked the streets, observing closely under cover of his urban anonymity, and whose observation was rewarded with artistic inspiration. As an artist figure, the flâneur was linked both to modernity and to its representation. What, then, of the woman writer? Were flânerie and its artistic rewards available to her as well? Janet Wolff’s argument that they were not provoked a flood of scholarship investigating the historical possibilities for women on urban streets and in other public places, along with a new interest in literature representing women’s metropolitan experiences.Footnote 9 While the scholarly debate about the possibility of a flâneuse has subsided, there remains much interest among historians, literary scholars, and cultural critics in women’s negotiation of urban space dominated by men in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Scholarship on the late twentieth- and twenty-first-century city has turned increasingly to gender’s intersections with class, race, and global modernity, reflecting both an increasingly heterogeneous population and literary writers’ engagement with that diversity.Footnote 10 Sexual harassment and the danger of sexual violence have continued to be horrifyingly relevant to representations of women’s relationship with urban space.

Scholars have employed nuanced readings of individual literary texts to examine how gender informs the experience and representation of the urban environment and of space more broadly. These readings have paid substantial dividends for our understanding of certain texts. They are also the basis on which scholars have formed theories about larger patterns in literary history. If we want to understand the wider cultural terrain, however, we need to look beyond the relatively small number of texts that we read, write about, and teach. We need to examine the vast majority of books that are, to a greater or lesser degree, obscure to critical practice. Of course, we cannot read thousands of books as we would one or a dozen. But computational methods give us new evidentiary inroads to a series of questions that traditional forms of analysis cannot address in full – questions like: What difference does the gender of fictional characters make to their geographic mobility? How does an author’s gender influence where a novel’s characters travel? Are there differences in the kinds of places men and women authors represent in their fiction, and do those differences vary by the gender of their characters? How have the answers to all of these questions changed over time, from the early nineteenth century to the early twenty-first? This study uses the new affordances of computational methods, combined with more traditional modes of humanistic inquiry, to answer these and other questions of longstanding interest in literary and cultural studies.

1.2 The Texts in This Study

As with any literary study, it’s important to understand the texts under analysis. We work with 21,347 books held by the HathiTrust digital library, the largest repository of digitized texts available for scholarly use. Our texts are the near entirety of the HathiTrust’s holdings that we determined, through library metadata and other tools discussed at the end of this section, to be English-language fiction published in Britain between 1800 and 2009. They are the near entirety in that we removed duplicate texts and any subsequent editions of popular works.

It’s important to note the consequences of our choice not to include, so far as possible, multiple editions of a given work. Our goal was to allow each book equal weight in our analysis, so that volumes by minor and forgotten writers would “count” as much as those by canonical figures in English letters. We chose, in other words, to focus on the production and marketing of literature more than the consumption of literature. A different study would have resulted from a corpus that included multiple editions of single works, one that would more closely track the consumption of literature, but at the cost of decreasing the representation of minor voices. Despite our choice, canonical and widely popular texts do have slightly greater weight in our corpus than do other texts, for two reasons. First, they are more likely to have been reprinted in forms that our algorithm didn’t detect: a novel might have been published under significantly different titles or with different author names over multiple centuries, or a popular author’s books may have reappeared in collected forms that do not signal their specific content. Still, it’s rare for a book to go even to a second edition, so the over-representation of canonical texts in this regard is fairly small (we estimate that between 0.9% and 2.8% of our titles are undetected reprints).

The second reason that canonical and pseudo-canonical texts are overrepresented in our corpus, despite our commitment to weighing equally all texts published in Britain, is that the academic libraries from which we source our texts are not equally likely to have collected every book. We chose to use HathiTrust’s holdings to assemble our corpus because it offered the largest number of fictional volumes available for computational processing, providing an unprecedented collection of popular, largely forgotten novels, as well as most of the usual subjects of critical attention. It does not, however, include everything published in Britain, in part because the collection comes mostly from academic libraries in the United States.Footnote 11 The British Library probably comes closer to a comprehensive collection of the British publishing industry, including many texts that were never acquired by American educational institutions. Books published in Britain that never made it to American universities were likely disproportionately “popular” rather than literary, including childrens’ books and pulp books, such as railway books, meant to be purchased, read once, and discarded. The British Library, however, despite a large-scale digitization program, has not made its texts publicly available for computational research. It is also the case that not all authors enjoyed equal access to formal publication. Even if our corpus did include every published book, there would exist a significant body of narrative fiction excluded due to the biases and priorities of the historical publishing industries.Footnote 12 We must, as Doris Lessing cautioned, “remember that for all the books we have in print, [there] are as many that have never reached print, have never been written down” (Golden Notebook, xxiv).

There is some evidence that the particular qualities of a sample of historical literary texts may make less difference than is often imagined. Research by Ted Underwood, Patrick Kimutis, and Jessica Witte comparing differently constructed subsets of fiction volumes drawn from the HathiTrust library shows that, for a wide range of problems, “trends of interest to researchers follow many of the same diachronic arcs,” suggesting that at least some patterns are “too durable to be purely an artifact of library collection practices.”Footnote 13 Further, comparisons of HathiTrust’s collection with corpora assembled from other sources – Publishers Weekly, for example, or a manually assembled corpus of novels available from diverse sources – showed similar trends in author and character gender composition over time (Underwood, Bamman, and Lee, “Transformations of Gender,” 3–7).

Further choices deserve comment. This study uses only works published in English, including translations of foreign-language books (we estimate between 9% and 10% of included volumes are translations, mostly from Western European languages). One could eliminate some of the translations via bibliographic metadata, but we have not attempted to do so, because we seek to survey as much of the British fiction market as possible. We want, in other words, to assess the books that were available to Anglophone British readers, regardless of their provenance. A different choice might have produced different results, though we have no evidence to suggest that translated books are necessarily different from nontranslated books in the dimensions of interest to us. Works published in Britain are of course not the same as works written by British authors, but there is a high degree of overlap (about 80% in our corpus, according to our estimates, though the fraction varies over time; see also Wilkens, “Too Isolated”).

It’s important to acknowledge that fiction is surprisingly difficult to detect. Libraries did not begin classifying genre until the late twentieth century. Even now, library metadata is inconsistent in labeling early books as “fiction” or “nonfiction.” According to Underwood, Kimutis, and Witte, a sample of pre-1900 fiction that relied purely on metadata “would leave out more than half of the fiction, and it might be biased specifically against obscure writers” (3; see also Underwood, “Understanding Genre”). Our identification of “fiction” is drawn from Underwood et al.’s algorithmic predictions over the whole of the HathiTrust library, setting our selection cutoff at volumes predicted to be no less than 80% likely to contain at least 80% fiction content. This probabilistic method means that our corpus erroneously excludes some fiction volumes and includes others that skilled human readers would not classify as fiction, though these are often marginal cases such as memoir, biography, travelogue, and narrative history. We begin our study in 1800 because HathiTrust’s coverage is sparse and uneven before that. We end our study in 2009, the most recent year available. Underwood, Kimutis, and Witte, in “NovelTM Datasets for English-Language Fiction, 1700–2009,” provide a rich discussion of the makeup of the HathiTrust collection.

1.3 Overview of Research Results

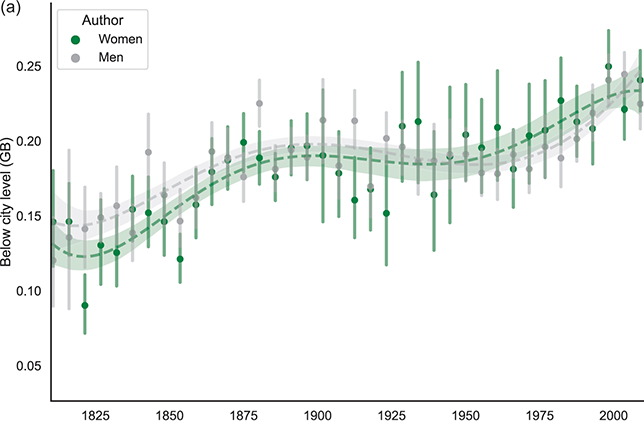

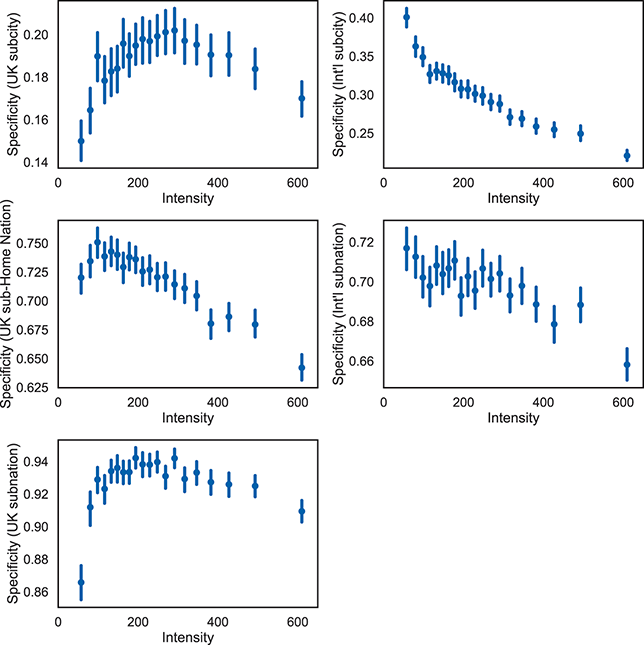

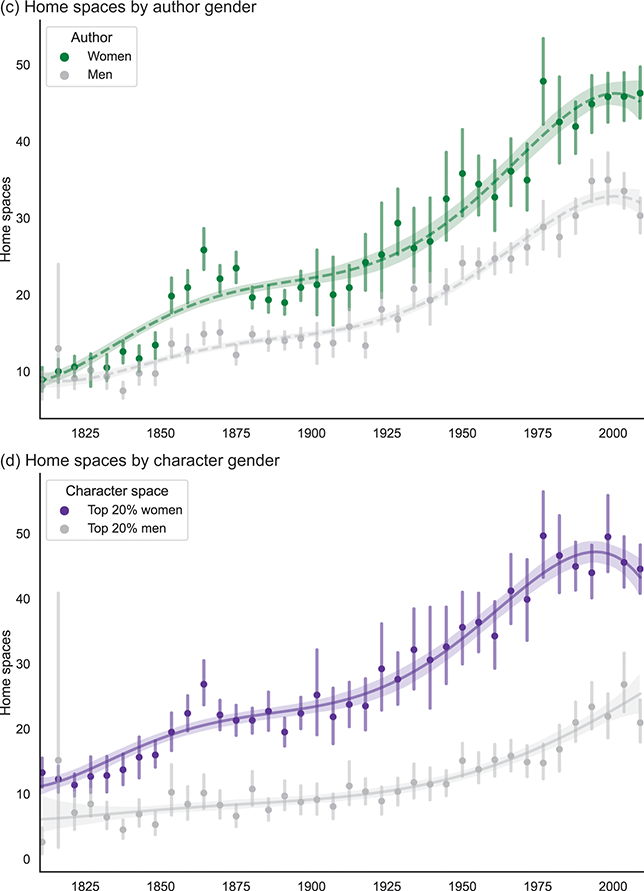

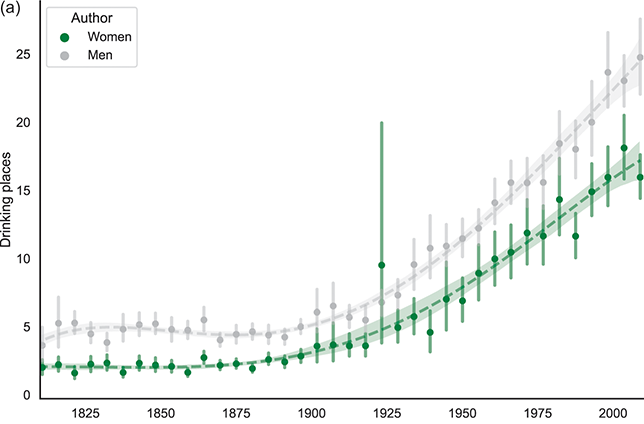

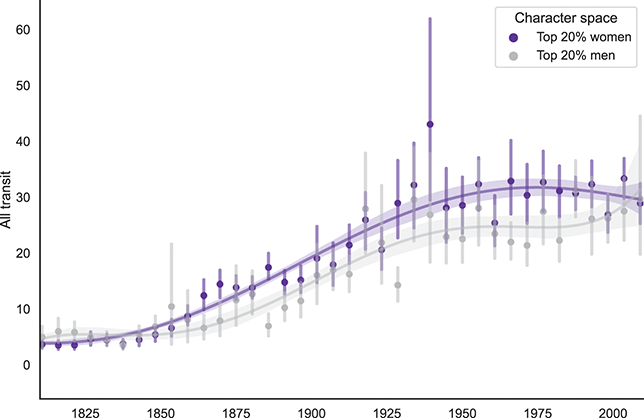

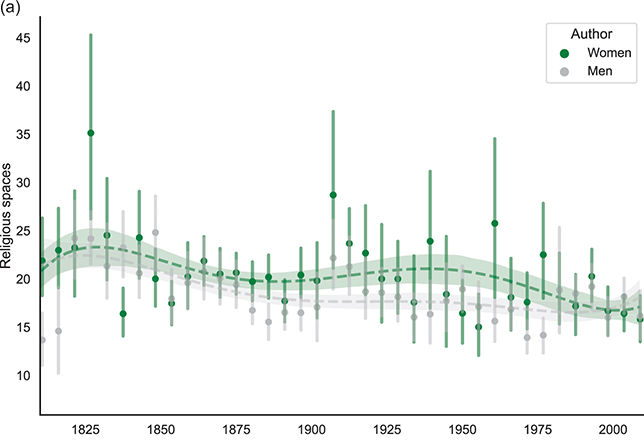

At the beginning of this section, we summarized the popular, if undersupported, critical consensus about the intersection of gender and literary geography over the past two centuries. This set of expectations imagines literature reflecting Western women’s increasing mobility over time as they moved out of the home and traveled more extensively beyond it. In opposition to this critical consensus, we demonstrate that books by men and women authors over the past two centuries of British literature showed relatively little difference in their characters’ overall mobility. The mobility of men and women characters, however, diverged much more sharply and the gap between them remained surprisingly consistent over time. We theorize that literary geography functioned less as a reflection of gender-determined differences in authors’ personal experience than as an index of other cultural forces that shaped conventionally masculine and feminine roles, such as the availability of formal education and opportunities for economic independence. In other words, authors expressed a multitude of constraints for women through geographic limitations for their characters. While opportunities for travel opened up to women over time, the ongoing constraint of women characters at the turn of the twenty-first century suggests that the physical world is not yet seen as fully available for women’s exploration. Furthermore, while we do find evidence of the doctrine of separate spheres – women authors and characters were more aligned with the home and male authors and characters were more aligned with streets and other public byways – we discover a surprising reversal of expectations in urban and natural spaces. In the British fiction we examine, cities were associated most frequently with women, while rural and natural spaces were most affiliated with men. This finding provides an opportunity not only to reevaluate the critical conflations of urban modernity with masculinity and of nature with women but to trace their roots in the history of textual acquisition and canon formation.

We will have much more to say about all of these findings in the sections ahead. But first, we must make a short detour through the mechanics of our work and the intellectual considerations they raise.

2 Gender and Language through Computation

As we noted in Section 1, this study involves 21,347 volumes of fiction published in Britain between 1800 and 2009 and digitized by the HathiTrust library consortium. Our work relies on two different types of information extracted from these books. The first concerns their use of spatial and geographic references. We’ll have more to say about that data in Section 3. The second concerns the gender performances of the books’ authors and characters. Here, we describe the process by which gender information was collected and the range of limitations attached to it.

There are two important points to make before we dig into the details of our gender data. First, we note that, like much research in digital humanities, our work is the product of many hands. The data we use concerning the gender identities of authors and characters in our corpus was produced by Ted Underwood, David Bamman, and Sabrina Lee and was originally used in their article “The Transformation of Gender in English-Language Fiction.” We cannot recommend that article highly enough to anyone who cares about the history of gender and literature.Footnote 14 Of course, responsibility for the accuracy of the data we use and for the suitability of the methods by which it was produced lie with us, even in cases where we weren’t the ones who wrote or ran the original code that produced it. We have made some small changes around the margins of the Underwood et al. dataset, and some much larger ones involving corpus selection, but when we describe the methods in this section, we want to be careful not to claim credit for the labor of others.

We believe that there are substantial benefits to working with existing data where possible. Beyond the practical advantages of efficiency and accessibility, using standard datasets helps to build a library of results that draw on shared resources. These results, in turn, help other researchers better understand the data and its limits, and they lend credibility to a baseline against which new work and new datasets can be evaluated. As quantitative methods spread more widely in the humanities, the value of widely used, well understood, and carefully vetted datasets, especially those linked to the HathiTrust library, seems certain to grow. That said, no dataset, no matter how well established, stands on its own. As we discuss in the next subsections, the data we use – whether produced directly by us or borrowed from others – is the product of human decisions, cultural processes, and technical constraints that stretch backward from our own desks through academic laboratories, cultural institutions, commercial concerns, and social formations over decades and centuries.

The second high-level point is that the model of gender we use for both authors and characters is partially binary, though our data allow us to treat a given book as occupying a position along a continuum between feminine and masculine. Each author and each fictional character in our corpus is labeled man, woman, or unknown. We make no algorithmic attempt to further divide or refine individual gender identities in our data. We do so because we believe that there are substantial benefits to working with these high-level, historically salient categories. Large-scale analysis of binary gender construction’s textual effects helps to reveal historical inequities and areas of gender convergence that may not match our critical expectations. It can also illuminate new aspects of the historical construction of gender and new aspects of literature’s role in gender performance. This is to say that binary approaches to classification, in combination with nonbinary aggregation of gendered characteristics, can do more to produce nuance than to undermine it. When we look at the “masculine-coded” and “feminine-coded” allocations of textual space, we discover that practically no book is all one or the other.

It should be obvious that we are not concerned on any occasion with biological sex. In the social realm of gender, our focus is on the aggregate interaction of individual performances with historically evolving positions. To minimize confusion on this point, and in keeping with current practice in gender studies, we generally avoid the adjectives female and male, preferring women and men or, rarely, feminine and masculine.

2.1 Methods: Author Gender

We examine the genders of both authors and fictional characters in our corpus. Each book that we study thus has at least two gender attributes: the (binary) gender of its author and the (nonbinary) fraction of narrative space devoted to men and women characters. Both of these attributes are derived directly from the data released by Underwood, Bamman, and Lee.

To assess authorial gender, Underwood et al. used US census records to match authors’ first names with prevailing use at the time of publication.Footnote 15 While British census records would have been preferable for our purposes, we find no evidence of large, systematic differences in the gender associations of first names between the United States and Britain over the last two centuries. Well-known cases of women authors who used male pseudonyms (i.e., George Eliot, George Sand) were hand-corrected, but there are surely other, less familiar cases that slipped through. There is an argument to be made that authors who chose to publish under a name with marked gender associations shouldn’t be “corrected” at all, since an author’s chosen name is a significant part of the gender performance of the text. But in the handful of prominent cases where we have overridden the gender implied by a pseudonym (as with Mary Ann Evans/George Eliot and Charlotte Brontë/Currer Bell), the author’s gender was widely known soon after the publication of their first novels. Names missing from the census records, including those identified only with initials, were assigned “unknown” gender. These books (3,358 in total, 15.7% of the corpus) were excluded from some of our analyses, but remain in the corpus and are included in cases where we do not focus on authorial gender. The composition of the full corpus by author gender is 30% women, 54% men, and (as noted) roughly 16% authors of unknown gender, though these percentages vary over time.

Census records are an imperfect proxy for author gender, of course. They are, moreover, inconsistently imperfect. Names missing from the census records, and therefore excluded, are more likely to be of non-Anglo origin. We therefore can expect that the corpus of books with an identified authorial gender may skew somewhat more Anglo-American in authorship than our original HathiTrust fiction corpus as a whole. This has the effect of making our “British” books – by which we mean books published in Britain – more likely to be “British” in the sense of being written by an author identified as British.

Straightforward errors – where an author’s name signals a gender that is inconsistent with the known historical record and where we might have wished to rectify the discrepancy – are possible but infrequent. In a few cases, a name once associated with men became ambiguous or given primarily to women, as has been the case with Alexis, Ashley, and Kim, but these are mostly handled by the historical nature of the name-lookup data. Errors are slightly more likely to occur when we’ve mistaken the date of first publication – when, for example, a reprint is misidentified as the original publication, sending the algorithm to search the census in the wrong period. But there are relatively few reprints in our corpus and even fewer gender-evolving names. Names that might refer to either a man or woman holder in a single historical moment (e.g., Evelyn, Claire, Sidney) are labeled “unknown,” the method requiring over 80% of a single gender to declare a result.

Overall, the accuracy of authorial gender prediction is better than we might have feared. Among authors, men are identified with precision of 0.99 and recall of 0.83, while women show better recall (0.90) but somewhat worse precision (0.91, still pretty good). Precision refers to the fraction of labeled instances that are correct; here, for example, among all the authors labeled women, 91% are indeed women, as determined by biographical research. Recall refers to the fraction of all instances in the data that are labeled correctly; in our case, for example, among all the authors in the corpus who should have been labeled women, we catch 90% of them. Authors labeled with unknown gender are, in a sample of cases where historical research is able to identify a gender, significantly more likely to be men than women (78.2% men, compared to 64.5% men among volumes with algorithmically labeled author gender). There is thus no evidence that women authors in our corpus were disproportionately likely to publish under gender-obscuring pseudonyms or initialisms.

2.2 Methods: Character Gender

The perceived gender of its author is one facet of a book’s gender performance. Another concerns the fictional characters within the book. To assess the latter, we used a modified version of Underwood et al.’s character gender data. Broadly speaking, this data was produced by identifying the characters present in a book, labeling all the words associated with each character, and inferring the gender of each character by reference to the gender-indicating words associated with it (pronouns and honorifics, for the most part). This data allows us to assign a gender “score” to each book, which measures the fraction of overall narrative attention devoted to women characters.

Character gender data was the product of a natural language processing pipeline called BookNLP, developed by David Bamman and built on standard natural language processing (NLP) tools used in computer science and computational linguistics.Footnote 16 To infer the probable binary gender of each character, BookNLP uses pronouns and gender-indicating honorifics, such as Mr., Mrs., Sir, and Lady. In effect, nearly all characters are gendered according to the pronouns and titles they use in a way that mirrors contemporary social practice. In cases where such direct evidence of gender performance is absent or ambiguous, the algorithm also considers low-noise historical name data. Because “I” does not unambiguously indicate gender, first-person narrators are not included, nor does the algorithm catch characters who aren’t given proper names, such as “teacher” or “the shopgirl.” But the process does produce good results. Underwood et al. report that women are identified with 94.7% precision/83.1% recall and men are identified with 91.3% precision/85.7% recall. While the algorithm fails to find 16.9% of women characters and 14.3% of men characters, when found, a character’s gender attribution matches what human readers would assign in over 90% of cases. Even more importantly, both for the arguments Underwood et al. present and for the arguments this Element will make, accuracy is relatively stable over time (3).Footnote 17

George Eliot’s Middlemarch (1871–72) provides a typical example of the method’s performance. Gender is correctly assigned to the major characters – Dorothea, Lydgate, Mr. Casaubon, and so forth – and we measure the fraction of narrative space (see later in this section) devoted to women at 0.371. This result may surprise readers who remember Dorothea as the novel’s protagonist, but it captures the book’s overall distribution of character space by (binary) gender.

There are obvious constraints imposed by this method, however. Chief among them is that we miss gender ambiguity. The pronoun “he” will trigger a male label no matter the character’s personal sense of gender identity. If the text calls Roger a man, a man he will be. An example helps us consider the implications of this fact. Radclyffe Hall, author of the important early queer bildungsroman Well of Loneliness, wrote a short story, “Miss Ogilvy Finds Herself” (1926/34), in which the protagonist is described as deeply uncomfortable in a woman’s body and conventional roles. Assigned female at birth, Ogilvy insisted as a child “that her real name was William and not Wilhelmina” (6). While, throughout her life, “Miss Ogilvy” struggles internally with the dissonance between her felt and attributed gender, the text continues to use feminine pronouns and the feminine title “Miss” to describe her, with one notable exception: pronouns shift to he/him in a sequence in which Ogilvy either dreams of or temporarily becomes (the text is ambiguous) the man she was in a previous life “thousands and thousands of years ago” (22). Because this prehistoric man is not named, he would not be identified in our study as a character, while Miss Ogilvy would simply be identified as a woman character. While our process flattens the much more complex and nuanced account of gender produced by the story, it does accurately capture the way in which she is labeled by the majority of the text and by the fictional world around her. Critics have followed the text in using she/her pronouns for Miss Ogilvy.

Gendered character-space is a measure of how much of a book concerns the lives of women and girls and of how much of it concerns the lives of men and boys. “Character-space” refers to those portions of a fictional book that are concerned with identified characters and words connected with those characters.Footnote 18 A character’s “space” includes the words used to narrate the actions they perform, the actions of which they are the objects, the adjectives that modify them, the nouns they possess, and the words they speak. We weighed each of these five ways of occupying fictional space equally. Our character-based gender score is then simply the amount of weighted character space devoted to women and girls, divided by the total gender-assigned character space of the book. A book that devotes exactly the same amount of attention to men and women characters would have a gender score of 0.5, or 50% women. We termed this score the “absolute” gender score of the text. For reference, Virginia Woolf’s novel Mrs. Dalloway (1925) measures close to even distribution of character space by gender (at 53% women).

As we noted earlier, an advantage of this book-level scoring method is that it allows us to treat a book as a mixture of masculine and feminine characterization, acknowledging and working with a continuum of literary gender performance even within a framework of binary character-level gender attribution. In some cases, we found it useful to compare books closer to the poles of gendered character space. But this left us with an interpretive dilemma. The books in our corpus contain, on average, significantly more character space devoted to men than to women (about twice as much, in fact). If we define the poles of character space in absolute terms (at 75% men or women, for instance), we will have many more books centered on men than on women (about 10 to 1 at that level), reflecting (accurately) the general hyperallocation of character space to men over the last 200 years.Footnote 19

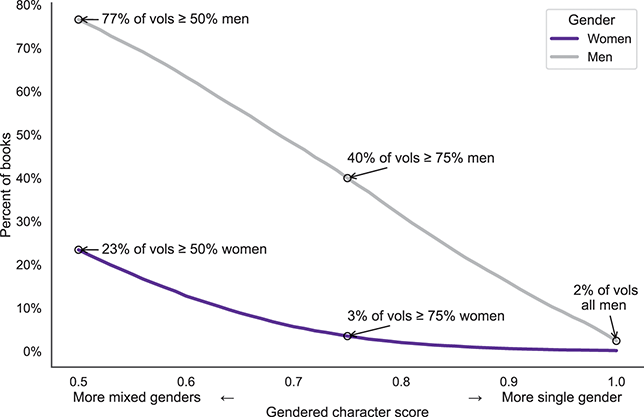

The stark difference in degrees of attention given to men and women characters is important here because it means that if we want to compare predominantly feminine texts and predominantly masculine texts by gender score alone, we would necessarily work with wildly different subcorpus sizes. The number of books in our corpus that have a gender score of at least 75% (mostly women) is just 746 (out of 21,347 volumes), compared to 8,528 books that have a gender score lower than 25% (mostly men). The quantity of women-centered books is enough for analyses of the period as a whole (1800–2009), but is generally not enough to produce high levels of statistical confidence when we split those 746 books into subsets by narrower time periods.Footnote 20 Comparing the size of these highly gender-skewed groups is a useful exercise in itself to appreciate this aspect of the sexist history of the book trade (Figure 1). It provides a vivid indication of whose stories have been deemed worth writing, reading, publishing, acquiring (by academic libraries), and preserving. One hopes it also provides motivation to change those practices.

Figure 1 Varying the definition of “mostly women” and “mostly men.” A plot of the percent of books in the corpus as a function of the computed character space score, grouped by predominant gender. Less than 25% of books are majority-women by this metric. Less than 5% are above three quarters women. Compare the male case: 75% of books devote the majority of their character space to men; 40% devote more than three quarters to men.

To address the problem of small samples and to implement an alternative critical model of what it means for a book to be oriented toward women characters, we took the top and bottom 20% of books ranked by character space. (We might have chosen a different cut point, of course.) Doing so gave us equal numbers of each (4,270 volumes in each class, to be exact), but set different limits of what it means for a book to be “mostly about men” (no more than 13% of character space devoted to women, in practice) or “mostly about women” (not less than 53% of character space devoted to women). To put this another way, texts that devote over 53% of their attention to women and girls are, by historical standards, highly women-centered, even when they devote nearly as much character space to men as to women. When, in subsequent sections, we analyze books that are “mostly about women” (or men) or that “skew toward women” (or men), these top and bottom 20% subsets are the groups to which we refer. On no occasion do we simply divide the corpus at the 50% level.

We selected the top and bottom 20% of books as measured across the entire corpus. This means that our two character-space subcorpora are of equal size and consistent meaning over the period, even as the historically contingent meaning of a women-centered work changed. (In some periods, the top 20% of books were less women-centered than at other periods.) This means that our two subcorpora do not represent all time periods equally. The women-centered books contain somewhat fewer books from the 1940–70 period, for example, since books published in those decades devoted an even smaller fraction of their character space to women than was the norm across the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

In short, there is no way to measure or subdivide our way out of the gender inequality of the last two hundred years of literary history. But we can choose different ways to assess that inequality, depending on which of its aspects we seek to understand. In the next section, we’ll see a similar phenomenon concerning the distribution of spatial attention in the corpus. We’ll also consider what’s involved in extracting geographic references from billions of words of literary narrative, what we can learn from patterns of literary geography, and what challenges we face when we try to map colloquial, historical, and imaginary places to specific coordinates on a globe. Just as we have found in the case of literary gender, measuring textual geography is possible only at the confluence of intellectual and practical concerns. Quantitative work is very much like conventional criticism in this way: we make assumptions, we set bounds, and we read, always, under constraints that enable us to make specific, situated claims.

3 Measuring Literary Space

If you’ve seen one piece of scholarship in the digital humanities or one DH project, there’s a good chance it involved a map. The maps and cartograms in Moretti’s Graphs, Maps, Trees help to identify social relationships and modes of spatial narration in nineteenth-century literature. Stanford’s Mapping the Republic of Letters produced what may be the most frequently seen DH visualization of the last two decades in their orange-on-black network map of eighteenth-century European correspondence (Edelstein et al.). Dozens of one-off projects include Google-based static and interactive maps of significant locations in specific novels or connected to the lives of individual authors.Footnote 21 Maps, it is safe to say, are a signature visual form of modern digital humanities.

Why is this? Why are maps so popular today when they were (and remain) rarely present in analog scholarship? The reasons are several. For one, paper maps are good to think with, but hard to publish. For all the Joyceans who have maps of Dublin on the walls of their offices, covered in color-coded pins that mark significant locations, how many have translated those scholarly devices into camera-ready, rights-cleared, publisher-approved illustrations? Who owns the rights to the base map? How much does that entity charge to republish it? How does one scale a full-color wall map of a square meter or more into a grayscale version legible at a quarter page? It has often thus proven (much) easier to describe in words a geospatial pattern identified on a map than it has been to display that pattern graphically.

Digital maps solve, or at least ameliorate, most of these practical problems, especially when the ultimate publication format is itself digital. Base maps from OpenStreetMap and (with some hand waving) from Google, Microsoft, Stamen, Mapbox, and others are freely available to academics. Web mapping interfaces handle scaling fairly well, support colors, are familiar from readers’ daily use, are generally suitable for collaborative use, and can be embedded within most digital publishing platforms. With a little more experience (or help from a university’s digital scholarship center), digital maps also work well with georectified archival basemaps, which can be important for historical work.

Maps are excellent exploratory tools, and digital maps solve a lot of the practical problems previously inherent in scholarly map use. Hence their ubiquity in digital scholarship. But maps’ range of potential applicability is narrower than one might imagine, even for work that is explicitly concerned with literary geography. Maps are, for the most part, mesoscale devices, best deployed in service of a moderate amount of text. They work well at the scale of the book or the small collection (poets’ travels in the English Lake District or Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha novels, for instance), where they can help to surface patterns of use that might otherwise escape readers’ attention. But maps can lose value at larger scales, where they become both visually overloaded and, in many cases, recapitulate other aspects of human geography (population density, for example, or topography).

The affinity between mapping and mesoscale collections helps to explain the early rise and continued relevance of cartography as a DH technique. Digital maps are computationally tractable, manageable by individual researchers, and appropriate to the kinds of collections with which many literary scholars are comfortable (and on which those scholars can lay hands via general-purpose resources like Project Gutenberg or specialized collections like the Whitman Archive). But you won’t find any maps in this Element, because the patterns we care about – the patterns of geographic usage that are relevant to the study of thousands of books published over more than two centuries – are not primarily visual in the sense encoded by maps. These patterns are instead temporal, demographic, political and, above all, statistical: how characters were distributed within and outside Britain over decades, or the differing associations between specific places and character genders in the work of men and women authors, or the shifting gender use of non-geographic spaces in urban and rural settings across historical events.

To identify and study these patterns requires bulk extraction of geospatial information from our corpus. This extraction is difficult and prone to certain errors, just as is the gender identification pipeline we described in Section 2. What we detail in Section 3.1 is how we carry it out, the underlying theory of the process, where some of the limits of the derived data lie, and how very recent developments in natural language processing methods do (and do not) offer the prospect of future improvements in the accuracy of the overall approach.

The remainder of this section will be most useful to those who want to follow the details of our method, whether to understand its affordances, to reproduce our results, or to carry out similar research on their own. Our aim has been to present technical material in accessible language. While some readers may prefer to skip directly to Section 4 – which they may do without overlooking substantive results – the information in the rest of this section will help to make clear the ways in which our investigation has been shaped by the tools at our disposal.

3.1 Spatial and Geolocation Extraction Methods

The first, and easiest, way to identify spatial and geographic references in unstructured text is to look for specific words that indicate places of interest.Footnote 22 We can find every instance of the generic terms like “street” or “bedroom,” for example, or of specific place names like “London” and “France,” provided we know in advance the words that are relevant to our problem. Indeed, we use this method for a subset of our results, especially in those cases where our interest is in space and spatial types (streets, domestic interiors) rather than in geography.

There are several important limitations to such dictionary-based methods. Most significantly, word counts do not cope well with polysemy. The noun “park” (a public green space) and the verb “park” (to stop and leave a vehicle) – to say nothing of a car park – are distinguished not by their orthography, but by their context. A version of the same problem holds for some geographic references, too. “Charlotte” might be a person or an American city. “Cambridge” is (almost) certainly a city, but is it British or American? We discuss these problems and our solutions to them in detail below.

Another limitation is practical. We source the digital texts in our corpus from the HathiTrust digital library. For volumes that are out of copyright, we can store and query the full text of each book locally, using whatever computational methods and resources are available to us. This makes it relatively quick and easy to perform iterative experiments (changing word lists, retaining or eliminating capitalization, identifying multi-word target terms [“car park,” “New York City”], and so on) on these public-domain texts. But Hathi cannot, for legal reasons, release to researchers (or to the public) the full text of in-copyright volumes. Unfortunately, in-copyright volumes make up a large portion (about half) of the books in our corpus. Specifically, nearly all the books in our corpus that were originally published after the early 1920s remain in copyright.

To work with in-copyright volumes – and thus to extend our study through most of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries – we have three options, each of which is useful, but none of which is perfect. We use each of these options for parts of our study.

1. We can use the HathiTrust Research Center’s (HTRC) extracted features dataset (Jett et al.). This dataset contains page-level bags of words (i.e., a list of the unique words that occur on a given page of a volume), each tagged with its computationally inferred part of speech (POS), along with the number of times the word-POS pair appeared on that page. The extracted features lose word order, which rules out many advanced analysis methods and simple counts of multi-word terms, but they have the merit of being freely available for local use and of covering the entirety of our corpus, including in-copyright volumes.

2. We can work with the HTRC’s data capsule system. These are remote computers that allow offline access to the full text of all Hathi volumes. What this means is that researchers can write analysis code to be run against Hathi’s full holdings on the HTRC’s systems. The output of that code is then reviewed by HTRC staff to ensure that it does not leak copyright-protected content (by writing out the full text of in-copyright volumes, for example) and, once cleared, the results are supplied back to the researcher. This is a good system for small- to medium-scale projects, but it’s hard to use for larger ones. It places significant strain on HTRC staff who review outputs. It is flatly unusable for outputs that are too large for realistic human review. It limits the computational power available to the equivalent of a single desktop, and it slows down iterative development by introducing time-consuming manual legal compliance review of every output. The data capsules are an excellent solution to a difficult legal problem for smaller projects, and we have used them in select cases, but they aren’t intended to replace direct access for large-scale work.

3. Finally, for library-scale work that includes in-copyright volumes, we can collaborate with HTRC developers to run our code on the HTRC’s full compute resources. This, too, involves human review of code and outputs, plus the significant overhead inherent in any research collaboration, but it allows us to run targeted, high-value (to us), computationally intensive workflows on a one-off basis, with outputs that we can then store locally for later analysis. This is the route we followed in devising and implementing the Textual Geographies project (txtgeo.net), which is the source of most of the geographic data we use in the present work.

We have used each of these access methods for parts of our study. We focus here on the third option, algorithmic extraction of named geographic locations from the full corpus, which we carried out in necessary collaboration with HTRC staff including Guangchen Ruan, Boris Capitanu, and Beth Plale. The second option is technically similar, though smaller in scale. We discuss the first option in more detail in Sections 6 and 7, in conjunction with those parts of our work that make extensive use of generic spatial terms rather than geographic data.

As we noted early in this section, polysemy is a problem for many dictionary-based methods. To address the uncertainties of textual reference to geographic locations, we implemented a multistep pipeline that first identified words and sequences of words in books that were used, in context, as geographic references.Footnote 23 These might include, for example, real and well-known places like “Berlin” or “Los Angeles,” but also obscure, fictional, or extraterrestrial locations (“Moon,” “Heaven,” “Yoknapatawpha County”). Our system relied on a conditional random field named entity recognition algorithm of the type introduced by Lafferty, McCallum, and Periera and implemented by Finkel et al. as part of the Stanford NLP toolset. Full details for the technically inclined are in the original papers, but the idea is that one can predict the role or meaning of a given word in context by examining the handful of words around it and comparing them to the words around other target terms of known type. Such an inference is a form of supervised learning; it depends on labeled training data to build the set of probabilities from which the algorithm makes its predictions. In more personifying terms, the algorithm learns not only that some words are used (almost) exclusively as place names, but also that phrases like “travel from … ” or “in the city of … ” are strong predictors that the next word (or words) will be a location (especially if capitalized). The algorithm thus also “knows” the difference between “a flight from Charlotte” and “my friend Charlotte” and can classify each “Charlotte” as a different type of named entity.

Naturally, predictive named entity recognition of this type is imperfect. Its accuracy depends on the regularities of the training data from which it extracts its contextual probabilities. If the training data is very different from the text on which the model is applied, that is, if the target text contains many terms or constructs that the model has never seen, the model’s accuracy will suffer. Poetic, catachrestic, and anachronistic language use poses special challenges (as it does for human readers). Existing statistical models are generally trained on contemporary nonfiction, rather than on the historical literary sources that make up, to a greater or lesser degree, our corpus, so our case is an especially challenging one. In fact, we tested a new model trained on nineteenth-century literary texts in an attempt to improve performance on the texts in our corpus. But we found that the larger size of the pretrained models supplied by Finkel et al., combined with the perhaps underappreciated historical stability of relevant aspects of English usage, led to superior accuracy when employing the stock models alone.

Readers familiar with recent developments in natural language processing may note that another approach to improving the performance of our system would involve using a large neural language model such as BERT or its many descendants to perform named entity recognition, perhaps fine-tuning on the literary training data that proved inadequate as the basis for a standalone model. Indeed, David Bamman and his group at Berkeley released such a system, an updated version of BookNLP, after our work was substantially complete.Footnote 24 These language models implement a form of transfer learning, in which model parameters learned from very large corpora provide a base representation that is then refined for a particular task and corpus. If we were beginning this research from scratch, there is no doubt that a large language model would be our point of departure. But the extra five or so percentage points of NER accuracy we would gain, while very welcome, are no panacea. We haven’t yet discussed the geolocation and hand correction steps that lie downstream from entity recognition and that have a significant impact on the overall performance of the system. Large language models, especially of the scale necessary to achieve the most impressive performance, are also expensive to train and to use, requiring specialized compute hardware to complete their calculations in acceptable time.Footnote 25 And there is, as of this writing, no possibility of using such models with in-copyright Hathi texts. In short, while a move to large language models wasn’t tenable for this project today, researchers in the field should be aware that such methods exist, and that they are the default starting point for most new work. Those researchers should also remain cognizant of the rapid pace of change in contemporary NLP, which is a source of both great excitement and of some disorientation.

Named entity recognition provides us with a list of the locations used in each volume. These locations range from the very specific (a building or business, a city square) to the very general (nations and continents), include both real and fictional places, and include a large number of variant names, spellings, and colloquial usages. To treat these locations as parts of a geographic system, we need to associate each of them with harmonized geographic and political data. We need to know, for instance, that Trafalgar Square is a public square located at 51.5080390° latitude, −0.1280690° longitude in the city of Westminster, which is part of the city (but not the City) of London, which is a locality in the district of Greater London, which is part of the top-level administrative area of England, which is part of the nation of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, which is, geographically at least, part of Europe. For most places, there is a simple, one-to-one or many-to-one mapping between a set of names by which a location may be referred and its canonical geopolitical data. We retrieve these mappings via Google’s Places and Geocoding services. The Places API is the comparatively expensive one, which knows that “Constantinople” and “Istanbul” refer to a historically continuous city-level entity and that “Londan” is almost certainly a typo (or digitization error) for “London.” From the Places API, we retrieve a set of probabilistically ranked unique identifiers for the geospatial entities to which a given string might refer. In most cases, we accept the most likely entity and use the Geocoding API to associate it with detailed geographic data. For relatively high-frequency places with significant ambiguity (“Cambridge” or “Richmond,” for example, but not “Paris,” because the instances in which a book uses “Paris” to mean “Paris, Texas” without writing out “Paris, Texas” are few), we determine the appropriate referent through a combination of heuristics (where and when the book was published, the nations containing the greatest number of its other named locations) and hand review.Footnote 26

Finally, we review by hand the places that occur most frequently in the corpus. That is, for every place name that occurs, on average, at least once every 5 million words (the equivalent of about once in every fifty volumes), we examine the location to which that place name is mapped, correcting the mapping globally or by volume where appropriate. Where relevant and practicable, we map historical places (“Soviet Union,” “Smyrna”) to their nearest modern equivalent (“Russia,” “İzmir”). By focusing on the most frequently occurring locations (about 1% of unique place names), we are able to review 70% of the total location occurrences in the corpus.

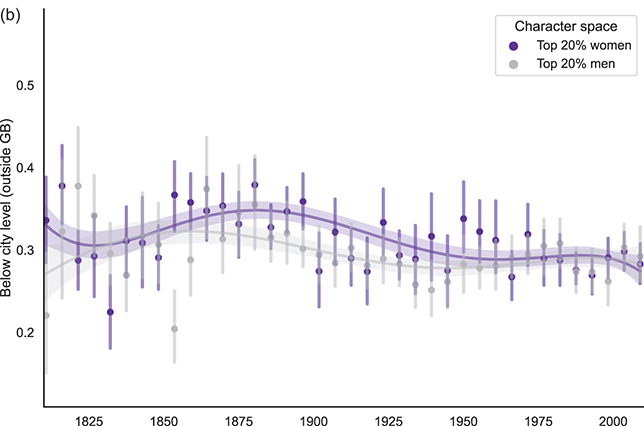

Machine learning researchers use a metric called F1 to assess the performance of information retrieval systems like ours. F1 balances two desired features: we want our system to identify all the places used in our corpus (that is, it should have high recall) and we want all the places we identify to be correct (it should have high precision). F1 is the harmonic mean of precision and recall. In our case, precision is 89.7%, recall is 71.0%, and F1 is 79.3%; we miss some locations, but the locations we do identify are generally correct. In many of the instances we care about, a more forgiving metric is appropriate, one that asks only if we have correctly identified the primary national or subnational (state, province, etc.) setting of a book by the preponderance of identified location references. We get the primary national setting right 96% of the time and the primary top-level subnational setting right 92% of the time.

On the whole, our pipeline performs well, though it is far from perfect. It is well suited to the comparative analysis of similarly constituted corpora and subcorpora. In these cases, the phenomena of interest are typically relative differences or rates of change that are robust to baseline errors, and the errors in any one volume can be offset in others. This statistical approach to robustness and error isn’t yet typical in literary-historical work, but it is the foundation of not just the physical sciences but the contemporary social sciences as well. We hope to show, in the sections ahead, that it is equally appropriate in cases that interest humanists.

4 Measuring Spatial Mobility

Few would dispute that, as a group, women in Britain have historically been less geographically mobile than men. Biological and social connections to childbirth and childrearing tended to root women of reproductive age, while fewer opportunities for education, employment, and adventure for women of all ages limited their horizons. Most readers would expect to see that difference in geographic mobility reflected in literary texts. Literature, after all, is often used as evidence of historical experience and, secondarily, is often regarded as an influence on extra-literary experience.

But the historical contours of that gendered difference in mobility are harder to pin down. For example, it seems self-evident that the discrepancy between men and women’s geographic range in both life and literature diminished between 1800 and 2009 as women closed a range of opportunity gaps. But was this a steady, linear change or a development characterized by rapid shifts and periods of stability (or even of retrenchment)? How might our corpus of more than 20,000 works of fiction provide (or fail to provide) evidence of a change in men and women’s geographical range, at least in the realm of the imagination? How, in other words, can we measure men and women’s comparative geographic mobility, as represented in literary texts?

In this section we discuss two proxies among many for geographic mobility: attention to international locations and spatial range. Since we are studying British fiction, we can summarize the former simply as the fraction of named locations that are outside the UK’s (present-day) borders. How much of a book’s geographic imagination is given to national cities, streets, and landmarks, and how much is directed at other nations and the places within them? Spatial range refers to the distance between named locations. A book set entirely in Greece, for example, would register as highly international but with little spatial range. We assess how men and women authors and their gendered characters compare on these two metrics, describe the process by which we derived these conclusions, and consider the implications of our findings for gender-based analysis of fictional texts.

4.1 International Attention

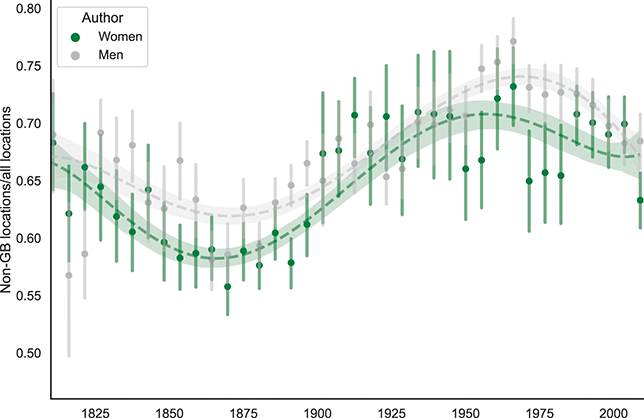

We find that, as expected, male authors name more international locations as a fraction of all locations mentioned than do women. This is the case in the cumulative 209 years of our study and it is also the case in both the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries, considered independently. But the difference is surprisingly modest. Cumulatively, named locations in books by men were about 68% international, while those by women were about 64% international, a difference of just 4 percentage points.Footnote 27 In some five-year intervals, the difference between the internationalism of men and women authors was reversed or was too small to be statistically significant; that is, there are brief periods during which we can’t be sure there was a difference at all.

The difference between men and women authors’ international attention was greatest in the second half of the nineteenth century (especially the 1850s, 1860s, and 1870s) and the second half of the twentieth century (especially the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s). In the first half of both centuries, there was no statistically significant gap in international attention between texts by men and those by women.

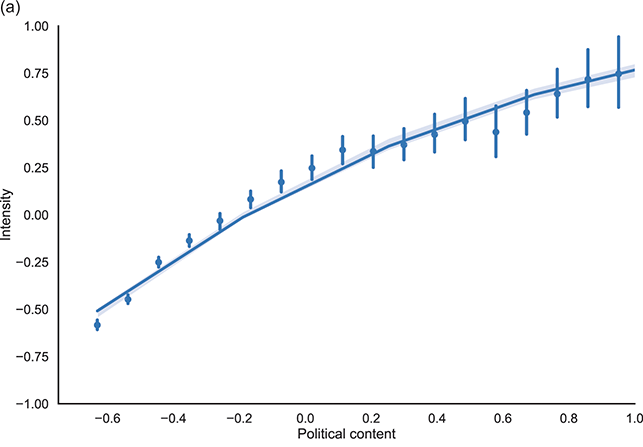

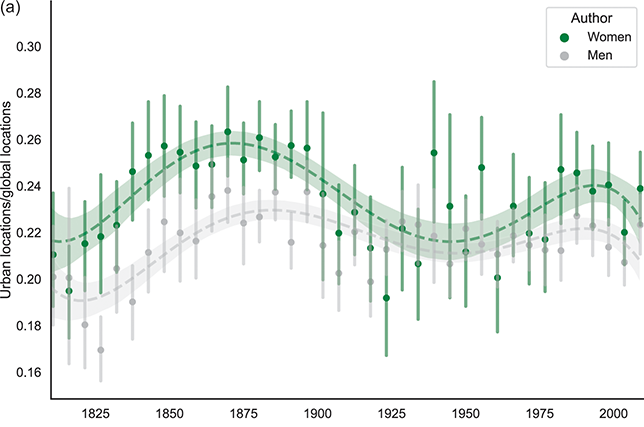

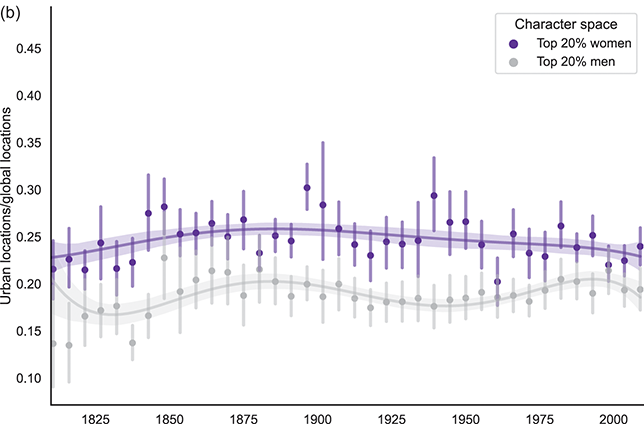

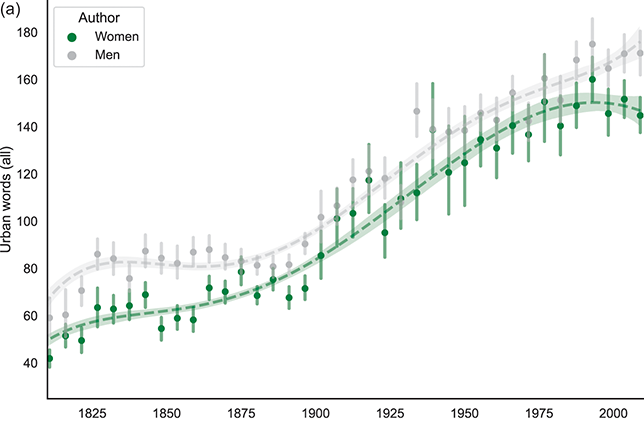

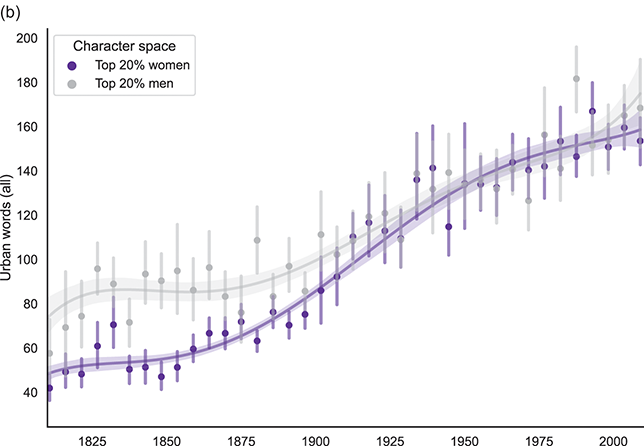

How to Read the Graphs

The y (vertical) axis corresponds to a dependent variable of interest, which is always labeled vertically along the axis itself. In Figure 2, the y axis shows the fraction of all named locations that were outside the (present-day) UK. The x (horizontal) axis corresponds to a different, independent variable, generally historical time as captured by the publication date of the books in the corpus.

Figure 2 International attention by author gender over time.

Each dot on the graph is the mean (average) value of the dependent variable as measured in all books published in a five-year bin. So, in Figure 2, each dot tells us the mean fraction of international locations in books published over five-year periods between 1810 and 2009 by men and by women. While the data we report and analyze begins with books published in 1800, we trim our figures at 1810 to avoid occasional visual artifacts that result from small samples in the earliest years. The vertical bar surrounding each dot is the 95% confidence interval for that mean. Longer bars indicate greater uncertainty of the mean, typically because the individual values are either widely dispersed or because there aren’t very many of them.

The line moving horizontally through time is the line of best fit (calculated using a fifth-order polynomial) through the data, with shading to show the 95% confidence interval of the fit. As with the vertical error bars, wider shaded regions indicate greater uncertainty concerning the exact location of the line of best fit. The line of best fit helps us to see trends across the two centuries, while the dots give us more detail in narrower time frames.

Colors and textures: Throughout the text, figures representing data aggregated by author gender (as in Figure 2) use green markers and dashed fit lines. Figures that show character gender use purple markers and solid fit lines. Figures that are not aggregated by gender use blue markers.

A more interesting finding may be just how large the international fractions were. Roughly two thirds of all geographic references were to places beyond British borders. A comparable study of American fiction over the same period found roughly 35%–40% of named locations were international in the US case (Wilkens, “Too Isolated”).

The fluctuations across the period are interesting, too. As we might expect, fiction of the early twentieth century – an era associated with cosmopolitan modernism and with two world wars – was more international (about 15% more) than was fiction of the late nineteenth century. However, this rise was partly making up ground lost from the fifty years before. Counterintuitively, the second half of the nineteenth century – when the British Empire was expanding – was a period of relative insularity (as measured by geographic references) in British fiction, though the fraction of international attention was still notably high in comparison with the American case (which was also much more stable over historical time). Critics have sometimes noted a potential suppression of direct engagement with the sites of empire during the height of colonial expansion, offering a range of possible explanations. Fredric Jameson, for one, has argued that, before World War I, “the relationship of domination between First and Third World was masked and displaced by an overriding (and perhaps ideological) consciousness of imperialism as being essentially a relationship between First World powers or the holders of Empire, and this consciousness tended to repress the more basic axis of otherness, and to raise issues of colonial reality only incidentally” (“Modernism and Imperialism”). And we have seen, in other contexts, that, even in the absence of explicit ideological suppression, certain types of geographical attention evolve only slowly, over decades or generations (Wilkens, “Literary Attention Lag”). Here, we offer the first large-scale evidence that, relatively speaking, British fiction did indeed engage more intensively with colonial and other extraterritorial locations in the twentieth century than during the nineteenth. There are other ways to assess international investments, of course; we will consider them in the sections ahead.

Table 1 lists some relatively well-known books that were close to the period average, far below it, and far above it, in the fraction of their locations allocated internationally. A few patterns quickly emerge. Unsurprisingly, the least international books take place entirely in the UK, often in circumscribed settings. These need not be rural settings, however: Margaret Oliphant’s A House in Bloomsbury and G. K. Chesterton’s The Napoleon of Notting Hill, for example, take place in particular neighborhoods of London (named in their very titles). As importantly, their imaginative universe is also local, with few references to foreign locations. In contrast, the most international books are set outside of the UK and include translated works by foreign writers (such as André Gide, Prometheus Illbound) and stories gathered from elsewhere (as with Mary Agnes Hamilton’s Greek Legends).

Table 1 Sample texts in each of four half-century periods that were far below average, about average, and far above average (for the period) in the fraction of named locations outside the UK.

| Period | Least international | Near average international | Most international |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1800–1850 |

|

|

|

| 1851–1900 |

|

|

|

| 1901–1950 |

|

|

|

| 1951–2009 |

| Samuel Selvon, Moses Migrating | Salman Rushdie, Midnight’s Children |

The works closer to average in their international fraction are perhaps more enlightening. Their major settings include the UK, but they are not exclusively set there. Elizabeth von Arnim’s The Enchanted April (1922), for example, has two settings: its early pages are set in London, while most of the remainder of the novel takes place in rural Italy. Though the majority of the narrative is set in Italy, the London portions are geographically intense, which explains why the book isn’t more international than around the period average of 70%. The lower, but still significant, average degree of internationalism in books of the late nineteenth century – 61% international – is well illustrated by George Moore’s Confessions of a Young Man (1888), which is set in Paris and London.

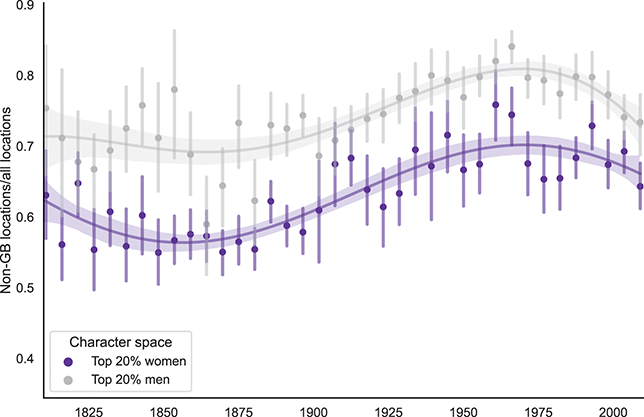

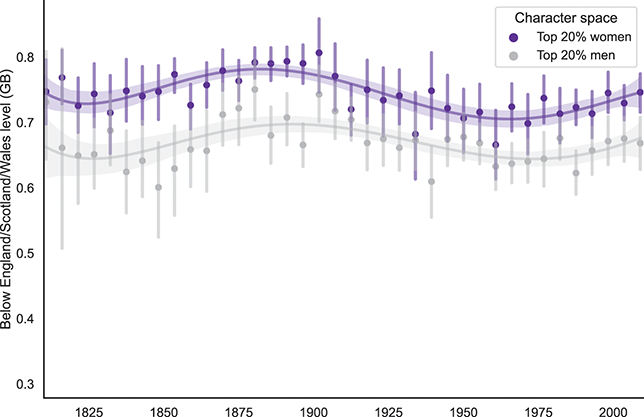

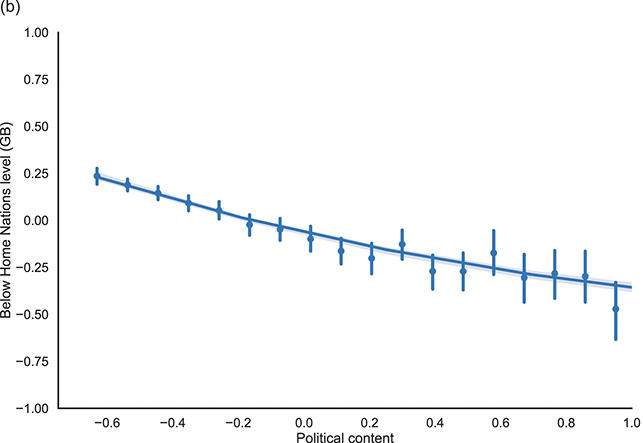

While author gender played only an apparently modest role in books’ degree of internationalism, differences in international geographic attention by gender were more pronounced when our unit of measurement is the poles of gendered character space.Footnote 28 Books mostly about men were distinctly more international in their location usage than were books mostly about women – about 20% more across the full corpus.Footnote 29 In terms of gendered character space, the gap between masculine and feminine international attention remained relatively consistent across the centuries of our study, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Books that are mostly about men have a higher average fraction of named locations outside the UK than do books mostly about women.

While conforming to prior expectations about men’s greater mobility, the results probably also reflect gendered literary genres and gendered character roles. Seafaring yarns and adventure tales tend to have predominantly male characters; characters with positions in government or international business have been more likely to be men from 1800 onward. But we know very little about the large-scale evolution of genres over the last two centuries, so it is difficult to disentangle shifts between genres that use men and women characters at different rates from changes in gender usage within genres over time. If the generic distribution of the HathiTrust corpus becomes better known in the future, we could directly disambiguate the findings to determine how much of the difference we see in gendered characters’ international links is the result of genre choices (spy fiction versus domestic romance novels, say) and how much difference occurs within the same genre. That said, the choice to write in a particular genre is also a choice about whether the story will likely contain more men or women. As Mikhail Bakhtin argued decades ago – and as Franco Moretti has more recently re-emphasized – where a book is set determines what will happen (Bakhtin, Dialogic; Moretti, Graphs, ch. 3). We would add that setting also determines to whom events will happen. If women-centered genres rise in popularity, that fact would signal a preference for a certain form of geographic attention, and vice versa, even in the absence of intra-generic geographic change.

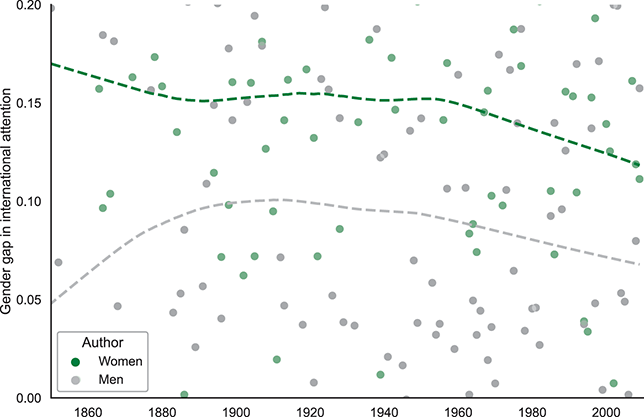

Intriguingly, women authors created greater difference between character genders than did men (Figure 4). In sum, women’s gender-skewed texts were more different (at 14.5 percentage points) in their international attention than were analogously imbalanced texts by men (at 9.5 percentage points). That is, the women-authored case has a nearly 50% greater gap than the male-authored one. The effect is that readers of books by women have consistently encountered larger gaps in international attention between women-heavy and men-heavy books than have readers of books by men. Whether women authors have been more conservative or more realistic, this pattern remained true across each fifty-year period, though the exact degree of difference fluctuated slightly, with the greatest variance in the earliest years of our study.Footnote 30 We flag this result specifically as meriting further investigation, since it conforms to no existing theory of gendered authorship of which we are aware.

Figure 4 Women authors allocate international space more differently between books about women and those about men than do male authors. We plot the difference (gap) in the annual raw fraction of international locations used in gender-skewed texts by women (green) and by men (black). Trend line is a LOESS estimate. Note that the horizontal axis begins at 1850; data are too sparse for useful comparison in the early decades of the nineteenth century.

The degree of international attention (as a fraction of all geographic attention), then, is one way to compare mobility. We’ve compared by author gender, by gendered character space in the most single-gender-dominant texts, and by men and women authors’ own differentiation in single-gender-dominant texts. We’ve seen that, although male authors’ degree of attention to international locations was only modestly greater than that of women authors, both categories of authors, but especially women, were decisive in associating international locations more with male characters.

Before we move on to further analysis of gender’s role in geographic attention, we should consider a more fine-grained problem: how the fraction of references to particular international locations changed over time – and how they didn’t. (We’ll also consider a different approach to this question, built around the average specificity of geographic references, in Section 5.) Table 2 shows the top international locations in each half century, as well as the most frequently occurring locations (of any type) in the corpus as a whole.Footnote 31 Paris and France were the most frequently referenced locations beyond the UK’s borders in every period, providing a measure of quantitative support for Pascale Casanova’s argument in The World Republic of Letters that Paris was the center of the (imagined) literary world. Ireland was prominent in early nineteenth-century British fiction, but diminishingly so in the decades and centuries that followed.Footnote 32 Rome and Italy were named more in the nineteenth century than in the twentieth, when their use declined. By the late nineteenth century, India rose in the ranks and would stay in the third position until after its independence. Africa, on the other hand, didn’t enter the top 10 until most of its colonized nations were achieving independence. Russia and Germany rose in the era of the world wars. Russia was the object of particular attention, probably boosted by widespread interest in – and concern about – the Russian Revolution, socialism, and communism. America and its most famous city rose in prominence as the centuries progressed. In sum, Western Europe was important in British literature throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, part of a preference for the near over the far. In contrast, the empire’s colonies make little appearance in the most frequently named places, Ireland and India being notable exceptions.

Table 2 Top international locations by era and, for reference, top overall locations in the full corpus (shaded cells in rightmost column).

| Rank | 1800– 1850 | 1851– 1900 | 1901– 1950 | 1951– 2009 | All locations, all years (per 100 k words) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Paris | Paris | Paris | Paris | London (18.3) |

| 2. | France | France | France | France | England (11.7) |

| 3. | Ireland | India | India | America | Paris (6.7) |

| 4. | Rome | Rome | Russia | New York | France (5.0) |

| 5. | Italy | Italy | Europe | Europe | India (2.8) |

| 6. | Spain | Europe | Rome | Africa | Europe (2.7) |

| 7. | Europe | Ireland | Germany | India | Rome (2.6) |

| 8. | Naples | America | America | Rome | America (2.5) |

| 9. | Dublin | Sydney | Ireland | Germany | Ireland (2.4) |

| 10. | India | New York | New York | Italy | Italy (2.3) |

4.2 Geographic Range

Internationalism is an important aspect of literary-geographic mobility. But it’s not the only one. Another approach to measuring imaginative mobility is to consider books’ spatial range, regardless of national boundaries. In this case, we seek to measure the geographic extent of each book. It’s a tricky metric to formulate; we want to account for large distances without being unduly influenced by fleeting mentions of far-off locales, and we want (all else being equal) to rank highly geographically diverse books above those that focus on a few widely separated places.

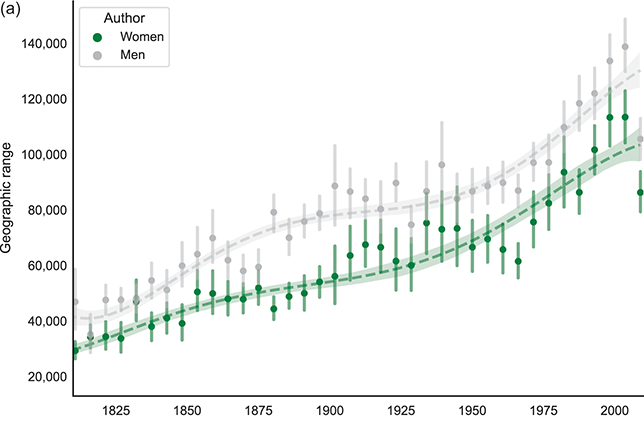

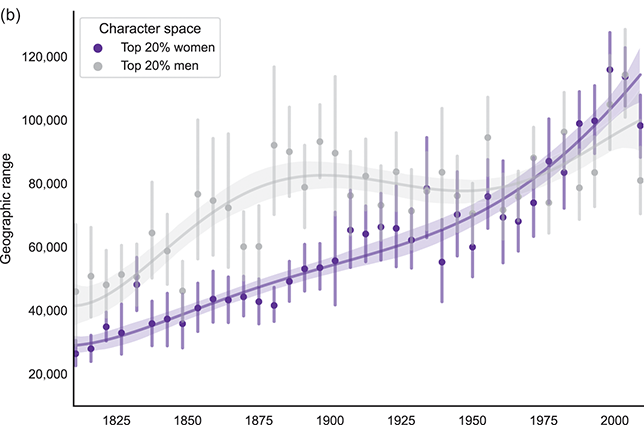

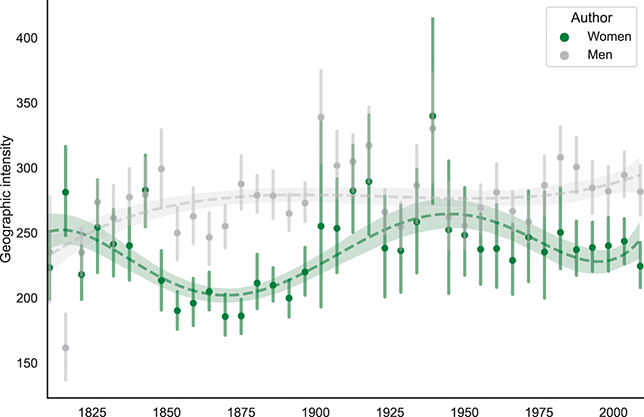

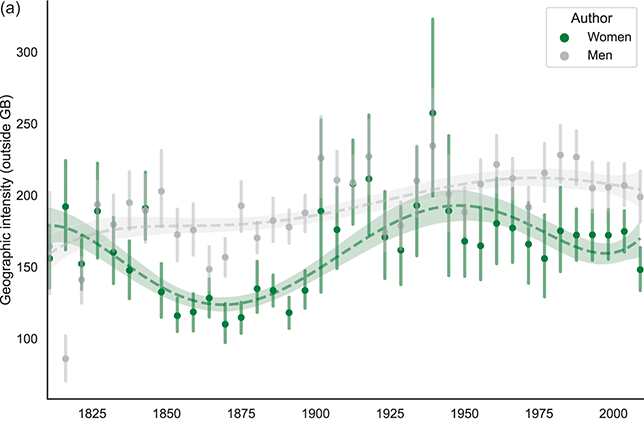

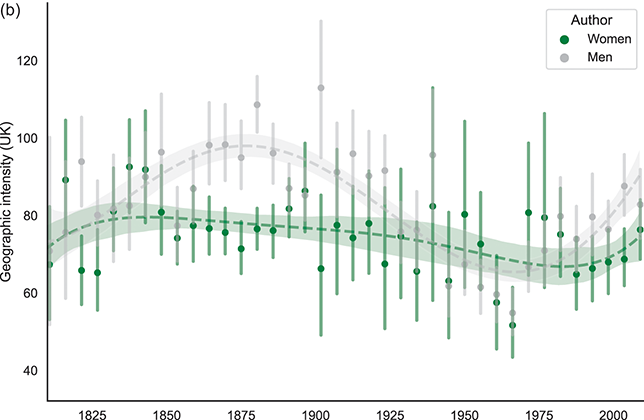

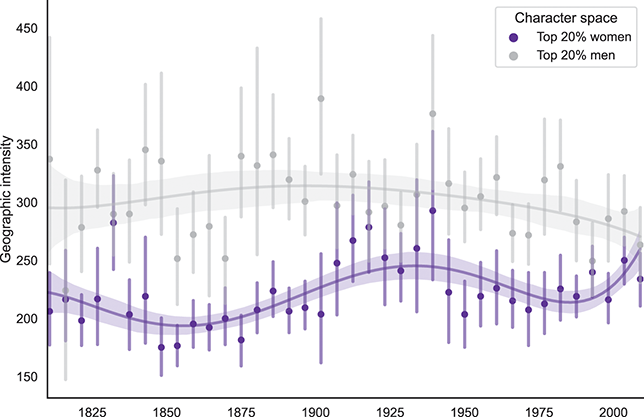

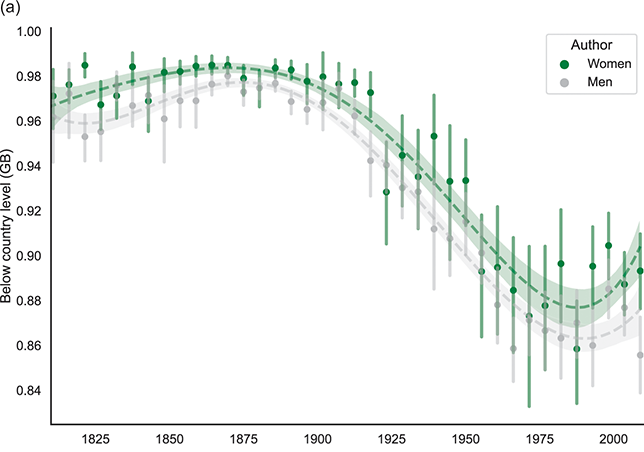

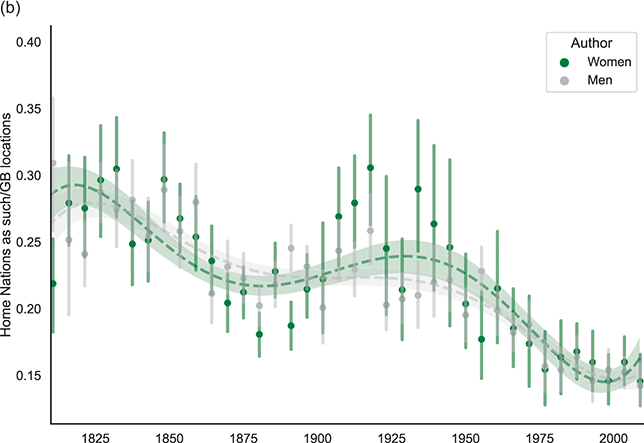

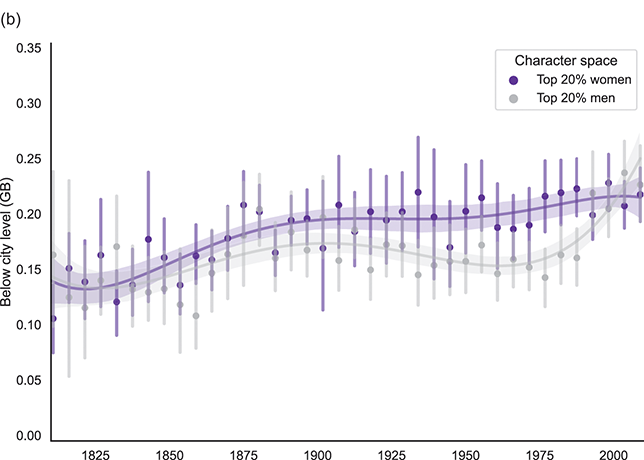

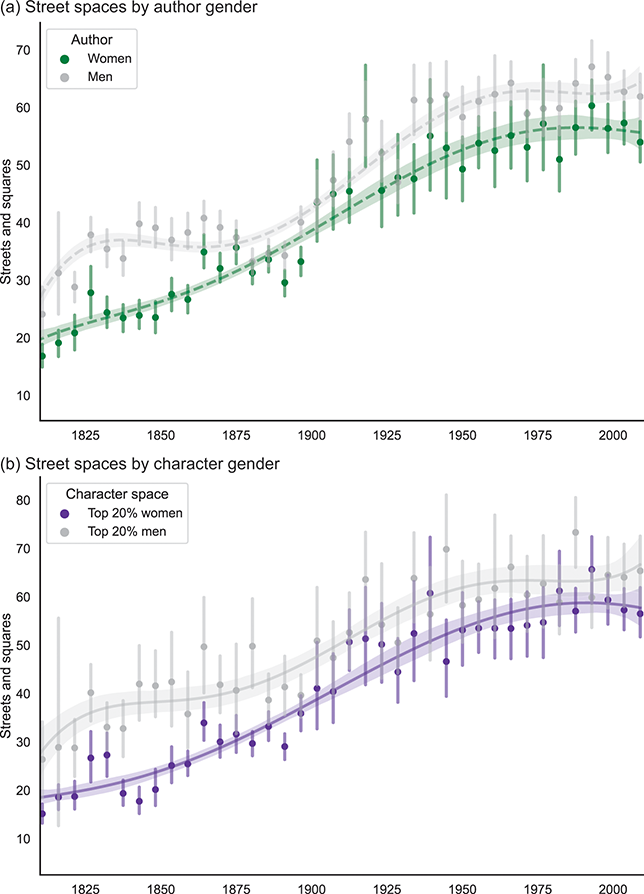

To calculate the geographic range of each book, we first restricted the locations under consideration to those that were among the 1,200 most frequently occurring in the corpus as a whole (to keep the total set of location pairs manageable). We then calculated the distance between every possible pair of these high-frequency places in a given text, scaled the distance between them according to their relative frequency in the volume, and weighted each pair by the fraction of all volume-level occurrences represented by members of the pair.