1. Introduction

Speakers of a heritage language (HL) are bilinguals who speak at home with their family a language that is different from the societal language (SL), normally because the family has a migration background. This means that their HL is their first language (L1); the SL is either acquired simultaneously with the HL or later in childhood as an early second language (L2). A HL is typically acquired under particular conditions of language exposure, which modulate the process of its acquisition (Benmamoun, Montrul & Polinsky, Reference Benmamoun, Montrul and Polinsky2013). In comparison to monolingual speakers, HL bilinguals acquire their HL in contexts of reduced exposure – often within the family and under the influence of the SL, which is the language of the wider community and the main language of schooling. This means that HL speakers are mainly exposed to the oral, colloquial variety of their HL and have very reduced literacy exposure to this language since formal instruction is absent or restricted to extra-curricular HL courses (Caloi & Torregrossa, Reference Caloi and Torregrossa2021; Flores, Kupisch & Rinke, Reference Flores, Kupisch, Rinke, Trifonas and Aravossitas2017a). Research has shown that formal instruction is an influential predictor of HL competence, with explicit grammar instruction leading to more consistent grammatical knowledge over time, especially with reference to linguistic structures that emerge late in the target language and are stabilized by instruction in monolingual acquisition (Bayram, Rothman, Iverson, Kupisch, Miller, Puig-Mayenco & Westergaard, Reference Bayram, Rothman, Iverson, Kupisch, Miller, Puig-Mayenco and Westergaard2017; Bowles & Torres, Reference Bowles, Torres, Montrul and Polinsky2021; Fernández & Bowles, Reference Fernández, Bowles and Bowlesin press; Flores & Rinke, Reference Flores and Rinke2020; Montrul, Reference Montrul2016). In addition, the dominant SL may impact the HL by generating patterns of cross-linguistic influence and leading to a divergent outcome from that of monolingual development (Scontras, Fuchs & Polinsky, Reference Scontras, Fuchs and Polinsky2015).

Although all these factors affecting HL acquisition have received increasing attention in the research field of bilingualism, the interplay between reduced exposure (being mostly restricted to the family context), limited literacy exposure and cross-linguistic influence on bilingual language development is still not fully understood. Given the observation that bilingual speakers show varying difficulty with different linguistic structures, an open question also concerns to what extent the mentioned factors affect the acquisition of structures at different levels of difficulty.

2. Background

2.1. The role of language exposure in the family, formal instruction and timing of acquisition in heritage language development

Heritage language acquisition takes place under very specific language exposure conditions. Children acquiring a HL are exposed to their HL from early on and within their families. As soon as they start to socialize in the dominant SL – for instance, through kindergarten, their time (and exposure) gets divided between the two languages, which leads to a reduced amount of exposure to the HL. This seems to lead to differences in the acquisition pace and outcomes between HL and monolingual children (Benmamoun et al., Reference Benmamoun, Montrul and Polinsky2013; Scontras et al., Reference Scontras, Fuchs and Polinsky2015).

A variety of language exposure variables have been considered to measure the relative amount of exposure that a bilingual child receives in each language. These factors include the time spent with interlocutors speaking one or the other language with the child, the frequency of use of one or the other language during leisure activities or the periods of stay in the country of origin. The age of acquisition (AoA) of the SL has also been included among these language exposure variables across several studies (see Gagarina & Klassert, Reference Gagarina and Klassert2018). It has been shown that a later onset of the SL (L2 AoA, henceforth) – which corresponds to a greater amount of exposure to the HL in the early years – has positive effects on HL acquisition (Armon-Lotem, Rose & Altman, Reference Armon-Lotem, Rose and Altman2021; Janssen, Meir, Baker & Armon-Lotem, Reference Janssen, Meir, Baker, Armon-Lotem, Grillo and Jepson2015; but see Armon-Lotem, Walters & Gagarina, Reference Armon-Lotem, Walters and Gagarina2011; Makrodimitris & Schulz, Reference Makrodimitris and Schulz2021 for evidence against this conclusion). However, the advantage of a later L2 AoA may be restricted to the initial stages of acquisition. At later stages, children with an earlier L2 AoA may catch up with their peers who were exposed later on (Gagarina & Klassert, Reference Gagarina and Klassert2018). The assessment of these language experience variables is mainly based on quantifications extracted from parental questionnaires (De Cat, Reference De Cat2020; Gollan, Starr & Ferreira, Reference Gollan, Starr and Ferreira2015; Gutiérrez-Clellen & Kreiter, Reference Gutiérrez-Clellen and Kreiter2003; Unsworth, Reference Unsworth, Schmid and Köpke2019), although it has been claimed that parental ratings may not be as reliable as required (Marchman, Martínez, Hurtado, Grüter & Fernald, Reference Marchman, Martínez, Hurtado, Grüter and Fernald2017). A growing body of research shows that variation in language exposure, especially reduced exposure to the HL, has consequences for HL development across several language domains, from phonology to morphosyntax (Flores, Santos, Jesus & Marques, Reference Flores, Santos, Jesus and Marques2017b; Gagarina & Klassert, Reference Gagarina and Klassert2018; Gutiérrez-Clellen & Kreiter, Reference Gutiérrez-Clellen and Kreiter2003; Hoff, Core, Place, Rumiche, Señor & Parra, Reference Hoff, Core, Place, Rumiche, Señor and Parra2012; Paradis, Reference Paradis2011; Paradis, Rusk, Duncan & Govindarajan, Reference Paradis, Rusk, Duncan and Govindarajan2017; Place & Hoff, Reference Place and Hoff2011; Rodina, Kupisch, Meir, Mitrofanova, Urek & Westergaard, Reference Rodina, Kupisch, Meir, Mitrofanova, Urek and Westergaard2020; Thordardottir, Reference Thordardottir2011; Torregrossa, Andreou, Bongartz & Tsimpli, Reference Torregrossa, Andreou, Bongartz and Tsimpli2021; Unsworth, Chondrogianni & Skarabela, Reference Unsworth, Chondrogianni and Skarabela2018).

Recent research has underlined the importance of qualitative aspects of language exposure for HL acquisition, above and beyond quantitative ones (see Blom & Soderstrom, Reference Blom and Soderstrom2020; Gollan et al., Reference Gollan, Starr and Ferreira2015). These aspects mainly relate to the richness and diversity of a child's language experience and may be operationalized in terms of the number of persons with whom the child interacts in one or the other language, the size of the immigrant community and a child's literacy habits (see De Cat, Reference De Cat2021 for a review). Literacy, in particular, provides children with the opportunity to be exposed to a variety of registers (Paradis, Reference Paradis2011). Children's socioeconomic status (SES henceforth) has often been considered as a proxy for richness (and, hence, quality) of language exposure (see De Cat, Reference De Cat2021 for discussion). SES is usually measured using information related to household income, parental occupation, or parents’ education. As stated by De Cat (Reference De Cat2021), the effect of SES on bilingual children's language development is not easy to identify, since SES may correlate or interact with other language exposure variables. Furthermore, several studies are often based on groups of speakers that are homogeneous in terms of SES. According to some authors, SES may predict at least some aspects of children's language knowledge, with lower degrees of SES corresponding to lower performance in some linguistic tasks (e.g., in vocabulary tasks; De Cat, Reference De Cat2021; Meir & Armon-Lotem, Reference Meir and Armon-Lotem2017).

In addition to variables related to the quality and quantity of language exposure, the effects of chronological age on children's abilities in the HL have been widely discussed. On the one hand, several studies show that HL children's competence in the HL increases with age (Rodina et al., Reference Rodina, Kupisch, Meir, Mitrofanova, Urek and Westergaard2020; Sopata, Długosz, Brehmer & Gielge, Reference Sopata, Długosz, Brehmer and Gielge2021), confirming a steady development of the HL even under conditions of reduced language exposure. On the other hand, some studies report that older HL speakers tend to perform similarly (or even worse) than younger ones (see, e.g., Chondrogianni & Schwartz, Reference Chondrogianni and Schwartz2020). In this case, the shift in dominance from the HL to the SL may correlate with language attrition or stagnation of HL development (Armon-Lotem et al., Reference Armon-Lotem, Rose and Altman2021).

An open question is whether the difficulty of the structure(s) to be acquired modulates the impact of language exposure variables and age on HL acquisition. In Rinke, Flores and Torregrossa (Reference Rinke, Flores, Torregrossa, Putman, Polinsky and Salmonsunder review), we account for the difficulty of structures in Portuguese in terms of different measures of linguistic complexity (e.g., derivational complexity, memory-based learning, context-dependency or non-linear form-function mappings). Furthermore, we show that the most complex structures correspond to the ones that are acquired late in monolingual language acquisition and are particularly challenging for HL children. These results are consistent with other studies showing that late acquired (or complex) structures seem to be more affected by language experience variables in both their quantitative and qualitative aspects than structures that are acquired early (Andreou, Torregrossa & Bongartz, Reference Andreou, Torregrossa, Bongartz, Dionne and Vidal Covas2021; Flores et al., Reference Flores, Kupisch, Rinke, Trifonas and Aravossitas2017a; Rinke & Flores, Reference Rinke and Flores2014; Schulz & Grimm, Reference Schulz and Grimm2019; Torregrossa, Caloi & Listanti, Reference Torregrossa, Caloi, Listanti and Romanoto appear).Footnote 1 For the stabilization of some of the difficult structures, exposure to formal language registers through schooling seems to be crucial (Bongartz & Torregrossa, Reference Bongartz and Torregrossa2020; Bowles & Torres, Reference Bowles, Torres, Montrul and Polinsky2021; Caloi & Torregrossa, Reference Caloi and Torregrossa2021; Rinke, Flores & Santos, Reference Rinke, Flores, Santos, Gabriel, Grünke and Thiele2019).

An additional factor that may impact the acquisition pace and outcomes exhibited by HL children is cross-linguistic influence. The outcomes of HL acquisition may diverge from those of monolingual language acquisition as a result of cross-linguistic influence from the SL, as has been shown in the domain of reference production (e.g., Sorace & Serratrice, Reference Sorace and Serratrice2009), gender assignment and agreement (Eichler, Jansen & Müller, Reference Eichler, Jansen and Müller2013; Montrul, Foote & Perpiñán, Reference Montrul, Foote, Perpiñán, Almazán, Bruhn and Valenzuela2008), and the interpretation of definite articles (Kupisch, Reference Kupisch2012; Montrul & Ionin, Reference Montrul and Ionin2010). However, only very few studies compare bilingual children of different language combinations to each other and, if they do so, they report contradictory findings. Some studies show that bilingual children speaking two languages that are typologically similar perform better than bilingual children speaking two typologically distant languages (see Blom, Boerma, Bosma, Cornips, van den Heuij & Timmermeister, Reference Blom, Boerma, Bosma, Cornips, van den Heuij and Timmermeister2019 on vocabulary; Serratrice, Sorace, Filiaci & Baldo, Reference Serratrice, Sorace, Filiaci and Baldo2012 on phenomena at the interface between morphosyntax and discourse). This suggests that cross-linguistic influence plays a relevant role in HL acquisition. Other studies have compared HL speakers with different SLs and have reported similar patterns of HL development independent of the contact language (Rinke & Flores, Reference Rinke and Flores2018; Rodina et al., Reference Rodina, Kupisch, Meir, Mitrofanova, Urek and Westergaard2020; Sorace & Serratrice, Reference Sorace and Serratrice2009; Torregrossa et al., Reference Torregrossa, Andreou, Bongartz and Tsimpli2021). Furthermore, cross-linguistic effects may be modulated by the difficulty of the structure to be acquired. For example, positive effects of language proximity may be especially visible with structures whose acquisition is particularly challenging for HL speakers.

2.2. The cloze-test as a measure for language proficiency

Cloze-tests consist of texts from which some parts have been deleted. The deletion may involve whole words, whole words except for the initial letter or only the second half of the word (see Hulstijn, Reference Hulstijn, Blom and Unsworth2010 for a review). Cloze-tests also differ from each other with respect to the criteria that guide word deletion. In some cloze-tests, specific words are deleted (e.g., the sevenths or eighth word from one gap to the other, as in the case of the fixed-ratio procedure). In other cloze-tests, researchers decide which type(s) of word(s) to delete (e.g., only functional words), based on the research question underlying their investigation, as in the case of the rational procedure, which will be used in the present study.

Cloze-tests are used to evaluate the participants’ knowledge of linguistic structures involving various language domains: lexicon, morphosyntax, orthography, pragmatics and discourse. Therefore, cloze-tests are viewed as integrative assessment tools, since participants have to access large parts of their linguistic knowledge to reconstruct the missing gap (Chung & Ahn, Reference Chung and Ahn2019). Participants need to “have the item in their vocabulary, to identify the item correctly based on the context, and to produce its correct grammatical and orthographical form” (Drackert & Timukova, Reference Drackert and Timukova2020, p. 123). Cloze-tests and their sub-types (such as c-tests) have been extensively used across different educational contexts such as language placement tests and as measures of language proficiency in experimental linguistic research (see Grotjahn & Drackert, Reference Grotjahn and Drackert2020 for an updated c-test bibliography; see also Brown, Reference Brown1980; Tremblay, Reference Tremblay2011; Tremblay & Garrison, Reference Tremblay, Garrison and Prior2008). However, most research on cloze-tests is conducted with adult foreign language learners, who acquired the assessed language in formal instruction settings. The validation of cloze-tests for other types of speakers, such as HL speakers, has been initiated only recently (Drackert & Timukova, Reference Drackert and Timukova2020; Luchkina, Ionin, Lysenko, Stoops & Suvorkina, Reference Luchkina, Ionin, Lysenko, Stoops and Suvorkina2021). Drackert and Timukova (Reference Drackert and Timukova2020) show that late L2 learners perform better than HL speakers in a cloze-test, mainly because the latter exhibit some deficits in orthographical knowledge (see also Mehlhorn, Reference Mehlhorn2016). The authors suggest to take this deficit into account when scoring the test by ignoring pure orthographic errors or considering partially correct answers as correct. When orthographic errors are not considered, cloze-tests turn out as reliable instruments for HL speakers’ language knowledge too (see also Luchkina et al., Reference Luchkina, Ionin, Lysenko, Stoops and Suvorkina2021 for a similar conclusion).

The administration of cloze-tests with children has been discussed since Taylor's (Reference Taylor1953) seminal work on the use of cloze-tests as predictors of American school children's reading skills. Lapkin and Swain (Reference Lapkin and Swain1977) attempted to use cloze-tests as instruments to assess language knowledge in English and French among children attending bilingual education programs. However, it should be considered that cloze-tests may not be suitable for children at initial school levels or HL children who are never exposed to written language (in the HL), since these tests are in written form and their use implies that children have developed reading and comprehension skills as well as discourse and narrative abilities.

All participants of our study attended classes of European Portuguese (EP, henceforth) as a HL and, hence, have all been exposed to written Portuguese to varying degrees (see Section 3.1).

2.3. Portuguese as a heritage language in Switzerland

The Basic Law of the Portuguese Educational System (1986) establishes that all Portuguese-descendant children have the constitutional right to attend Portuguese classes. These are provided by the network Portuguese Teaching Abroad (Ensino de Português no Estrangeiro/EPE), which is organized and financed by the Portuguese Ministry of Foreign Affairs through the Camões, Institute of Cooperation and Language, I.P. The network offers EP HL classes in all countries that host a significant number of Portuguese emigrants.

Switzerland has an important role in the EPE network since it hosts a large Portuguese-speaking community. It is the third-largest immigrant group (13.1%), after the Italian (15.2%) and the German (14.7%) communities (OFS, 2017). Although the number of students attending EP HL classes in Switzerland has had a downward tendency in the last years, the network still serves around 8000 pupils, in the age span of 6 to 18 years, and employed 75 teachers in the school year 2019-2020. Importantly, EP HL classes take place in Swiss schools after the regular school activities: these classes are not integrated in the curriculum and attendance is voluntary (Gonçalves & Vinzentin, Reference Gonçalves, Vinzentin, Souza and Melo-Pfeifer2021).

When the EPE network was founded, the main purpose of EP HL classes was to teach Portuguese as the mother tongue. Due to current changes in the social, economic and migration paradigms, EP HL teachers are nowadays faced with a great diversity of their students’ linguistic competence in Portuguese (many children are 3rd generation migrants). Thus, the main purpose of EPE now is to support the construction of the plurilingual and pluricultural identity of Portuguese-descendant children and youth in the diaspora, by also facilitating their integration into host countries’ education systems. The Swiss cantons support the EP HL classes by providing the physical space for the classes and through diverse common pedagogical projects (Gonçalves & Zingg, Reference Gonçalves and Zingg2022), even if these classes are not integrated into the Swiss school system. Due to Switzerland's particular linguistic landscape with four national languages (German, French, Italian, Romansh), the official school curriculum includes other national languages as foreign languages in addition to English. The policies regarding the type and number of curricular foreign languages vary from canton to canton.

3. The study

We analyse the competence of 180 Portuguese-descendant HL children ranging in age from 8;06 to 16 years and living in Switzerland. The children were exposed to EP from birth and belonged to three different groups, depending on the respective SL (French, German or Italian). All children attended extra-curricular EP HL classes. Data collection included a written cloze-test in Portuguese, in order to assess children's mastery of different linguistic structures (Section 3.2.2), a detailed background questionnaire for parents, in order to collect information related to children's age, exposure to Portuguese and to the SL across different contexts (family, wider community and formal instruction) and L2 AoA (Section 3.2.1).

We aim to understand how children's overall performance in the cloze-test is affected by input factors, such as the amount of use of the HL at home and degree of formal instruction in Portuguese, age as well as the respective contact language. In addition, we investigate whether those factors are also relevant if we discriminate structures that are ‘easy’ (generally more target-like) or ‘difficult’ (generally less target-like) in the test.

As a first step, we aim to identify the structures that pose particular difficulties to the children, as indicated by the accuracy scores associated with the different items of the cloze-test. We will perform a cluster analysis in order to understand whether the items cluster into groups of similar difficulty. We will observe whether the items clustering around the highest degree of difficulty correspond to the structures that have been shown to be particularly vulnerable in HL and monolingual acquisition. In particular, we expect children to exhibit more difficulties with clitic pronouns, different types of subordinate clauses and prepositions (see Costa & Lobo, Reference Costa, Lobo, Baauw, Drijkoningen and Pinto2007; Costa, Lobo & Silva, Reference Costa, Lobo and Silva2009; Flores, Rinke & Sopata, Reference Flores, Rinke and Sopata2020 on the acquisition of clitics; Costa, Reference Costa2006; Costa, Lobo & Silva, Reference Costa, Lobo and Silva2011; Jesus, Marques & Santos, Reference Jesus, Marques and Santos2019 on the acquisition of different types of subordinate clauses; Brito, Reference Brito2018 on the acquisition of preposition in L2 Portuguese).

As a second step, we will consider the variables that have been shown to affect bilingual children's language acquisition, such as age – as a proxy for children's cognitive maturity –, HL input in the family, the number of family members that speak Portuguese to the children – as a proxy for a variety of input –, formal instruction in Portuguese, L2 AoA and children's SES (see Section 2.1). To achieve this, we will correlate the children's accuracy scores in the cloze-test with the language background variables as extracted from the parental questionnaires. We hypothesize that children's overall performance on the cloze-test benefits from the quantity and quality of input in Portuguese. Furthermore, if cumulative input to Portuguese affects accuracy in the cloze-test, children with a later L2 AoA (French, German and Italian) should exhibit better performance than the ones with an earlier L2 AoA, since they received more input in Portuguese over the years. However, based on the studies reported in Section 2.1, the variables related to the quality of input (such as formal instruction and variety of input) should be more relevant than the ones related to the quantity of input (such as the amount of exposure in the family and L2 AoA). Differences in SES may be reflected in differences in language acquisition outcomes, with children of higher SES performing better than children of lower SES (Section 2.1). Finally, we should observe that older children perform better than younger ones if our hypothesis that the acquisition of certain structures (especially the most difficult ones) requires time is correct.

The third step in our analysis concerns the interaction of the background variables with the level of difficulty of the items as identified based on the previous cluster analysis. We will run a generalized linear mixed-effects model with accuracy of each answer (accurate vs. inaccurate) as the outcome variable and the interaction between the level of difficulty of the corresponding item and the background variables as predictor. We hypothesize that ‘easier’ structures should be less sensitive to background variables than ‘more difficult’ ones.

As a final step, we investigate how cross-linguistic effects affect the extent to which children provide a correct (or incorrect) answer to the items of the cloze-test. We will run a generalized linear mixed-effects model with response accuracy as the dependent variable and language combination as the independent variable. Furthermore, we will consider the interaction between language combination and the degree of difficulty of the items (as defined by the previous cluster analysis), because we do not exclude that typological proximity between the HL and the SL facilitates the acquisition of the most difficult structures. For example, the French–Portuguese and Italian–Portuguese children may perform better in the production of clitics than the German–Portuguese children, since clitics are available in French and Italian, but not in German.

Table 1 provides an overview of all predictions of our study.

Table 1. Overview of the predictions of the study

3.1. Participants

We tested 180 Portuguese HL children ranging in age from 8;06 to 16 (M: 11;07; SD: 1;10). At the time of testing, the children were living in Switzerland in three different linguistic areas, in which the SL was either French, German or Italian. Therefore, we divided the children in three groups: 60 French–Portuguese, 60 German–Portuguese and 60 Italian–Portuguese children. Due to an error in the data anonymization process, we lost one cloze-test by an Italian–Portuguese child. Therefore, the analysis will be based on 59 cloze-test results of the Italian–Portuguese children. The children were recruited from the language classes offered by the Instituto Camões. All children acquired Portuguese from birth and the SL before the age of 6, except for 10 children who acquired it between 7 and 12 years. In the language background questionnaire (see Section 3.2.1), most parents reported that their children were born in Switzerland (N: 127), others that their children were born in Portugal (N: 43) and few either reported that the children were born in a country different from Switzerland and Portugal or they did not provide any answer to this specific question (N: 9). No moving between linguistically diverse Swiss cantons was reported.

Before the study, the parents provided written informed consent. Both the parents and the teachers reported that none of the children had prior identified speech, hearing or visual impairment. The study was approved by the ethics committee for Social and Human Sciences of the University of Minho (reference CEICSH 016/2019).

3.2. Materials

3.2.1. Background questionnaires

We administered a questionnaire (Correia & Flores, Reference Correia and Flores2021) targeting children's age, SES, language exposure to Portuguese and the SL at home and to Portuguese in HL classrooms and L2 AoA to the parents.

Children's SES was assessed based on the educational level of the mother and the father, following Calvo and Bialystok (Reference Calvo and Bialystok2014). In Portugal, the education system consists of four cycles extended over 12 years. For each parent, we asked if they obtained a degree in the first, second, third or fourth cycle (high school), a university degree or a post-graduate education degree (e.g., a master's or a doctoral program). The answers were scored using a 6-point Likert-type scale, with “1” representing the lowest educational level (first cycle) and “6” the highest one (post-graduate education). For each child, we calculated the mean between the degree of education of each parent. This score was our measure of children's SES.

We asked the parents how many family members spoke Portuguese to the child and with which frequency this happened. The questionnaire reported a list of family members including mother, father, stepmother, stepfather, siblings (maximum 3) and grandparents living in the same household (maximum 4). We also gave two open options indicated with “other”. For each family member, the parents had to answer with which frequency s/he spoke Portuguese to the child, choosing between “never in Portuguese, always in French/German/Italian”, “rarely in Portuguese, usually in French/German/Italian”, “half in Portuguese, half in French/German/Italian”, “usually in Portuguese, rarely in French/German/Italian” and “always in Portuguese and never in French/German/Italian”. We scored the answers using a scale from 1 (never Portuguese) to 5 (always Portuguese). We took the sum of the scores as a measure of the amount of input that the child received in Portuguese in the family. For example, if the parents wrote that the mother and the father usually spoke Portuguese to the child (both corresponding to 4 points) and one brother did it always (5 points), the child was associated with two values, i.e., 3 for the number of family members speaking Portuguese to the child and 13 for the amount of input in Portuguese in the family.

We also asked for how many years the children had been attending the Portuguese HL classes and for how many hours per week these took place. We multiplied the number of years by the number of hours and the average number of school weeks per year (i.e., 32). We considered this product as a measure of the amount of instruction that the children received in Portuguese. For example, a child that had been attending HL classes 2.5 hours per week for 2 years was associated with a score of 160 (i.e., 2.5 x 32 x 2).

Finally, we asked the parents to indicate at which age the child was first exposed to the SL (French, German or Italian), giving the possibility to report the age either in months or in years. We converted all answers into months.

3.2.2. The cloze-test in Portuguese

The task

Children's language proficiency in Portuguese was assessed using a cloze-test. Since no cloze-test for Portuguese was available at the time we conducted the study, we created a cloze-test specifically for school-age children ranging from ages 8 to 16, based on the methodology for the design of cloze-tests as reported in previous studies (see Section 2.2). We relied on a rational procedure, which allowed us to select target words concerning domains that have been shown to be particularly vulnerable in HL acquisition (see below for a list of structures). In other words, our test is informed by linguistic criteria. Our target words were of both the functional and content types. For functional words, we deleted the whole word or provided the initial letter in order to facilitate completion and restrict the number of possible answers. For content words, we provided the first half of the word (as is usually done in a c-test) for the same reasons. Overall, the cloze-test consisted of 40 items targeting different types of structures. Our large-scale study allowed us to provide robust data on the validity of this test for the age range investigated in this study. As shown above, successful performance on the cloze-test requires vocabulary and morphosyntactic knowledge. The test involves children's literacy abilities, too, given that the task is administered in written form.

We created the cloze-test based on a short narrative modelled after the B3 story of the Edmonton Narrative Norms Instrument (ENNI; Bongartz & Torregrossa, Reference Bongartz and Torregrossa2020; Schneider, Dubé & Hayward, Reference Schneider, Dubé and Hayward2005). We decided to develop a narrative-based task since some target structures were related to syntax-discourse interface phenomena (such as pronouns, clitic left dislocations and adverbial clauses). A narrative-based task allowed for a more ecological and reliable way to assess children's mastery of these structures than a cloze-test based on sentences that are not connected to each other. Therefore, it should be considered that the test also involved children's text comprehension abilities, which represent an important component of their literacy abilities.

Table S1 (in Supplementary Materials 1) reports a complete list of all sentences and items and Figure S1 provides an example of the cloze-test administered to the children. We designed the test to assess children's proficiency in Portuguese as related to different linguistic domains, i.e., nominal, verbal, prepositional and sentential domain. We refer to the Supplementary Materials for a classification of the items in these four domains. In each domain, we included items of different complexity (cf. Rinke et al., submitted for a complete review).

Procedure

The cloze-test was administered in paper form during the HL classes. The paper contained the text with gaps as well as three figures representing episodes of the narrative (Figure S1). The pictures were meant to support children (especially the youngest ones) in the interpretation of the narrative and make the test child-friendly. The children were told that they were going to read a narrative in which some words or parts of words were missing. The gaps indicated the length of the words or the missing parts. The children had to fill in the gaps, considering that each gap corresponded to only one letter. We gave the children 30 minutes to complete the test. Children were not allowed to use dictionaries or to talk to each other.

Analysis

There were four coding options: correct, incorrect, missing, or not expected but correct. For the analysis, we coded the correct and unexpected (but correct) answers as ‘correct’ (1) and the incorrect and missing answers as ‘incorrect’ (0).Footnote 2 All answers that were coded as unexpected but correct were checked by one of the authors of this paper and another native speaker of EP before being coded definitively as correct. For instance, for item [20], the expected answer was ao ‘to’. However, the answer do ‘of” was considered as acceptable too. Taking the generally low orthographic competence of HL children into consideration, spelling errors were ignored, i.e., an item with a spelling error was considered correct (e.g., felises instead of felizes), even when the number of gaps was not respected (e.g., lindisimo instead of lindíssimo) – see Section 2.2 for discussion.

4. Results

4.1. Background questionnaires

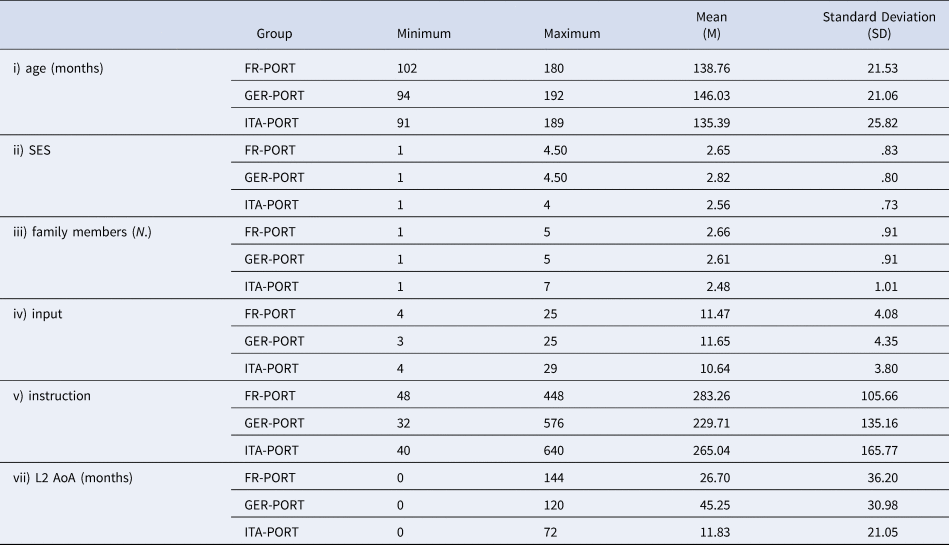

Table 2 reports the minimum, maximum, means and standard deviations for: i) children's age; ii) children's SES; iii) the number of family members that spoke Portuguese to the children; iv) quantity of input in Portuguese; v) amount of formal instruction in Portuguese; vi) children's L2 AoA. The results are reported for each language combination separately (French–Portuguese, German–Portuguese and Italian–Portuguese). We refer to Section 3.2.1 for a description of how each measure was calculated.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for children's age (in months), socio-economic status (SES), number of family members speaking Portuguese to the children, amount of input in Portuguese, amount of formal instruction in Portuguese and age of acquisition of the SL in months (L2 AoA). The statistics are reported for each language combination.

For each measure reported in Table 2, we performed a one-way anova analysis using the aov() function in R, in order to test whether the three groups differed from each other. If the anova-test was significant, we used the Tukey HSD (R function: TukeyHSD ()) for pairwise comparisons. However, if the assumptions for running an anova-test were not met, we ran the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test (R function: kruskal.test()) and used the Dunn's test for pairwise comparisons (R function: dunnTest(); package FSA, see Ogle, Doll, Wheeler & Dinno, Reference Ogle, Doll, Wheeler and Dinno2021).

The three groups did not differ from each other in any of the language or literacy exposure variables, i.e., the number of family members speaking Portuguese (χ2(2) = 1.25, p = .54), the amount of input in Portuguese (χ2(2) = 3.28, p = .19) and the amount of formal instruction in Portuguese (χ2(2) = 5.23, p = .07). We did not find any difference in the families’ SES either (χ2(2) = 2.60, p = .27). By contrast, the Kruskal-Wallis test is significant for children's age (χ2(2) = 6.83, p = .03), since the German–Portuguese children are slightly older than the Italian–Portuguese ones (z = 2.53, p = .03). Furthermore, the three groups differ from each other in the L2 AoA (χ2(2) = 28.73, p < .001), with the Italian–Portuguese children exhibiting the earliest L2 AoA (Italian), compared to the L2 AoA of the French–Portuguese children (French) (z = 2.13, p = .03) or the German–Portuguese children (German) (z = 5.31, p < .001). Furthermore, the French–Portuguese children were exposed to French earlier than the German–Portuguese children were to German (z = −3.38, p = .001)Footnote 3.

4.2. Cloze-test

4.2.1. Item analysis

We start by identifying the structures that pose particular difficulties to the children, as indicated by the accuracy scores associated with the different items of the cloze-test across children. Subsequently, we perform a cluster analysis, in order to understand whether the items cluster into groups of similar difficulty. We refer to Table S2 in Supplementary Materials for the total number, mean and standard deviation (per child) of each type of answer provided by the children (correct, unexpected correct, incorrect and missing, with the former two categories being classified as correct and the latter two as incorrect).

We conducted a Cronbach's alpha reliability analysis on the items of the cloze-test, using the alpha() function of the ‘psych’ package in R (Revelle, Reference Revelle2021), in order to understand whether the items of the cloze-test were internally consistent as a measure of language proficiency in Portuguese (Section 2.2). This analysis revealed that the reliability of our cloze-test is excellent, with an alpha of .95. We did not notice any increase in the Cronbach's alpha when dropping the items one by one.

Figure 1 shows the number of correct answers given by the children for each item of the cloze-test. The maximum score would correspond to 179 points if all 179 children provided a correct answer. The item flores at the top of the figure was associated with the greatest amount of correct answers (N: 170), whereas the item que_REL was associated with the lowest amount (N: 51).

Figure 1. Accuracy score of the 40 items of the cloze-test. The accuracy score corresponds to the number of children who provided a correct answer to the item. The most difficult items appear on the bottom of the figure, the easiest ones on the top.

We conducted a hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) in order to classify the items represented in Figure 1 into groups based on their accuracy scores across participants. The aim of this analysis was to understand which items exhibited a similar degree of difficulty. In other words, we wanted to identify a discrete number of levels of difficulty (alias accuracy) into which items cluster. First, we calculated all the pairwise distances between the rows in the dataset (each corresponding to an item) by means of the daisy() function in the ‘cluster’ package in R (Maechler, Rousseeuw, Struyf, Hubert & Hornik, Reference Maechler, Rousseeuw, Struyf, Hubert and Hornik2021), using Gower's distance. Then, we used the distances as inputs to the function hclust() for hierarchical cluster analysis. The resulting dendrogram reported in Figure 2 shows that the items clustered in two main groups of difficulty. The second group (on the right of the figure) contained a lower number of items than the first group (on the left of the figure). The items in the second group were: a_CLITIC [15], ajudá-los [33], balões [36], com [35], lhe [9], lo [7], pedirem [28], pela [2], por [34], qual [21], que_COMP [18], que_CONS [14], que_REL [12], repara [5], vem [30]. We used the Silhouette method to validate that 2 represents the optimal number of clusters in the present dataset (see Figure S2 in Supplementary Materials).

Figure 2. Dendrogram showing the result of the hierarchical cluster analysis of the items of the cloze-test based on their accuracy, using Ward's linkage and Gower's distance.

4.2.2. Correlation of the background variables with each other and with the accuracy scores in the cloze-test

We will now consider different variables that have been shown to affect HL children's language acquisition (as extracted from the parental questionnaires) and show their correlation with children's accuracy scores in the cloze-test.

Table 3 reports the correlation matrix of the variables considered in the present study. The accuracy score in the cloze-test corresponded to the number of correct answers given by each child. We found a significant correlation at a .01 level between the accuracy scores in the cloze-test and children's age, the number of family members speaking Portuguese to the children and the amount of formal instruction in Portuguese. There was a strong correlation between the number of persons speaking Portuguese to the child and the quantity of input in Portuguese to which the children were exposed. This was because the measure of the quantity of input – as assessed in this paper – referenced the number of persons speaking Portuguese to the children (see Section 3.2.1). We will take into account the strong correlation between these two variables in the next steps of our analysis, combining them into a single variable. We also found a moderate correlation between children's age and the amount of formal instruction in Portuguese. However, this correlation was not strong enough to justify the combination of these variables into a single factor. The L2 AoA was not correlated with children's overall accuracy.

Table 3. Correlation matrix related to the correlations between the accuracy scores in the cloze-test and the background variables considered in the present study. The correlation coefficients in bold indicate statistical significance at a .01 level.

4.2.3. The effects of background variables and level of difficulty on response accuracy

In the next step, we take into consideration the interaction of the background variables with the levels of difficulty identified based on the previous cluster analysis in section 4.2.1. More precisely, we intend to understand how the background variables considered in this study predict children's response accuracy and how their effect varies based on the level of difficulty of the items of the cloze-test (Level 1 vs. Level 2 based on the classification in Section 4.2.1). We used R (R Core Team, 2021) and the lme4 (Bates, Maechler, Bolker & Walker, Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2015) to conduct a generalized linear mixed-effects model with accuracy as the dependent variable (0 = inaccurate, 1 = accurate). As fixed effects, we considered the interaction between the level of difficulty of the item (Level 1 vs. Level 2) and most of the background variables reported above (age, family members, input, instruction and L2 AoA) as well as SES as the main effect, since we did not expect the effect of SES on the acquisition of different linguistic structures to vary based on the difficulty of the structures themselves (Section 2.1). We used sum contrast coding (−.50/.50) for the factor level of difficulty. After centering all fixed effects, we combined the variables input and family members into a single composite variable that we called input2 since, in the previous section, we noticed that the variables input and family members correlated strongly with each other. We used the scoreItems() function of the ‘psych’ package in R (Revelle, Reference Revelle2021), which calculated the average score between the two variables. The new score had excellent reliability (Cronbach's alpha = .92). We specified random intercepts for participants.Footnote 4

Table 4 reports the outcome of the generalized linear mixed-model analysis. The positive estimate for the intercept, as well as the associated p-value, show that accurate answers were significantly above chance. As expected, based on the cluster analysis in 4.2.1, we found a significant effect of the level of difficulty, showing that the log odds of providing an accurate answer decrease in association with structures at Level 2 of difficulty. Among the background variables, we did not find an effect of input 2 (family input), but we found an effect of age and amount of instruction: their positive estimates indicate that the log odds of providing an accurate answer increase with age and under a greater amount of formal instruction in Portuguese. Furthermore, we found a significant interaction between the amount of instruction in Portuguese and Level 2 of the difficulty of the items. The corresponding negative estimate suggests that the logit slope is – as a function of the amount of instruction – lower in the group of items at Level 2 of difficulty compared to the items at Level 1.

Table 4. Parameters of the generalized linear model analysis related to the association between children's response accuracy and different background variables, considering also their interaction with the level of difficulty of the items of the cloze-test. The fixed effects, their estimates, standard errors (SE), z-scores and p-values are given.

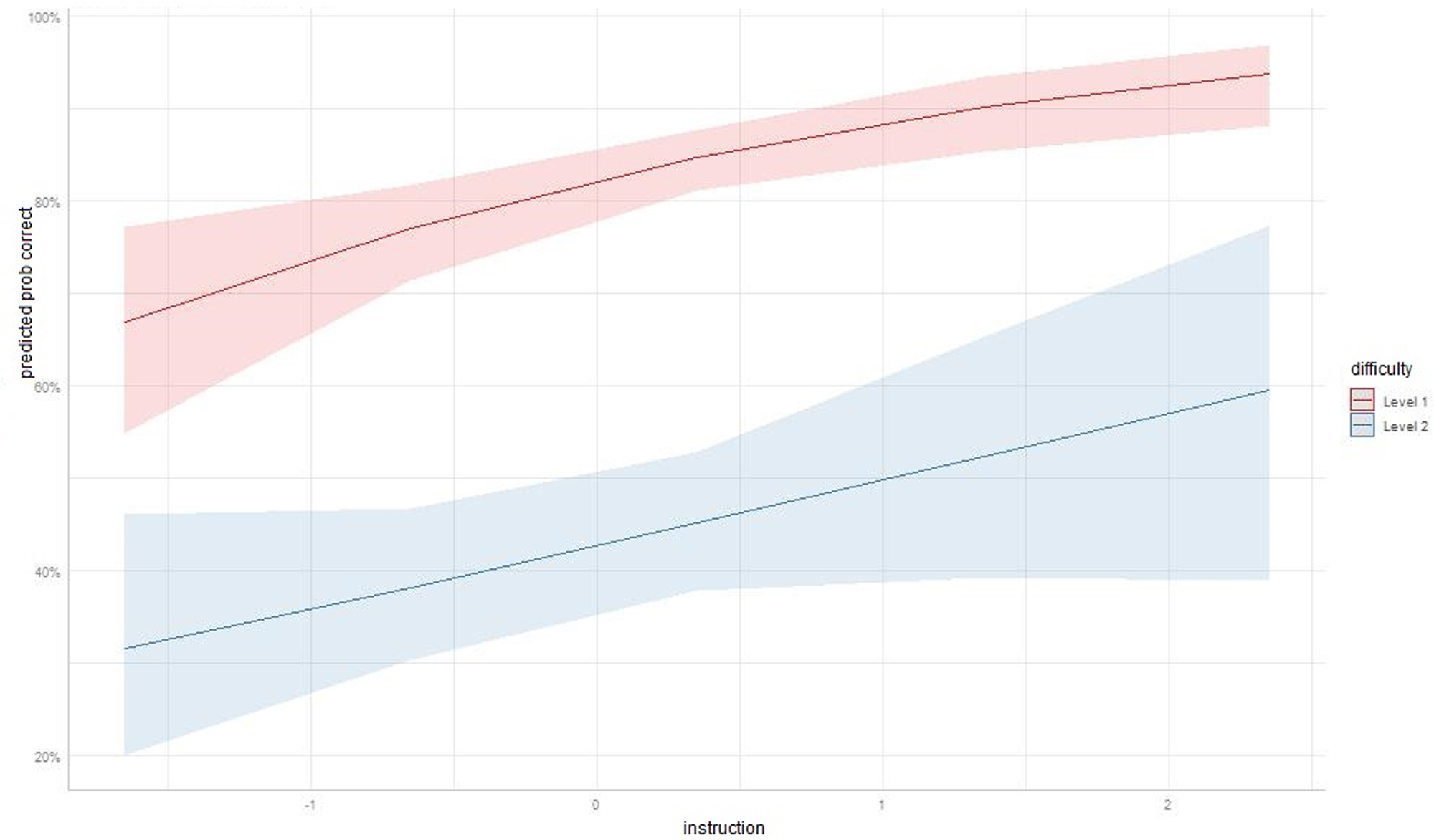

Figure 3 plots the predicted probability of producing a correct answer as a function of the amount of instruction across the two levels of difficulty. It shows that an increase in the amount of instruction of 1 unit (from −1.65 to −.65) leads to an increase in the probability of observing an accurate answer of 10% (from 67% to 77%) among the items at Level 1 and to an increase of 6% among the items at Level 2 (from 32% to 38%). We did not find any interaction between age and Level 2 of difficulty, i.e., age affects accuracy across all items.

Figure 3. Predicted probability of a correct answer as a function of the amount of instruction in Portuguese across items at the two levels of difficulty (Level 1 in the upper line and Level 2 in the lower line) considered in the study. The shaded lines indicate a 95% confidence interval. We plotted the predicted probabilities as derived by the ggpredict() function in the ‘ggeffects’ package (Lüdecke 2018).

From the observation of Figure 3, two other conclusions can be drawn. First, an increase in the amount of instruction in Portuguese leads to an increase in the probability of an accurate answer both among the items at Level 1 and Level 2 of difficulty. However, under a greater amount of instruction, the probability of a correct answer tends to plateau among the items at Level 1, but it increases steadily among the items at Level 2. Second, the probability of a correct answer in association with the lowest amount of instruction (on the left edge of Figure 3) is much higher with the items at Level 1 (i.e., around 67%) than the items at Level 2 (around 32%). This indicates that a great amount of instruction is not necessary to achieve a high probability of a correct answer with items at Level 1. In contrast, a relatively high degree of accuracy (around 60%) with items at Level 2 can be achieved only in association with the greatest amount of instruction as reported in the questionnaires.

As a last step in the glmer-analysis, we used the r2_tjur() function of the ‘performance’ package (Lüdecke, Ben-Shachar, Patil, Waggoner & Makowski, Reference Lüdecke, Ben-Shachar, Patil, Waggoner and Makowski2021) to calculate the Coefficient of Discrimination of the model. This analysis shows that the fixed effects account for 36% of the variation in the dependent variable (whether the children provided a correct or an incorrect answer).

4.2.4. The effects of language combination on response accuracy

Finally, we investigate how the language combination affected children's response accuracy in the cloze-test. First, we conducted a generalized linear mixed-effects model with accuracy as the dependent variable (0 = inaccurate, 1 = accurate) and language combination as the fixed effect, specifying random intercepts for participants.Footnote 5 We chose the German–Portuguese children as the reference level. The positive estimate for the intercept as well as the associated p-value show that accurate answers were significantly above chance for this group (β = .91, SE = .19, z = 4.69, p < .001). We observed no increase nor decrease in the log odds of providing a correct answer, which holds for both the French–Portuguese (β = −.31, SE = .27, z = −1.13, p = .26) and the Italian–Portuguese children (β = −.09, SE = .27, z = −.33, p = .74). These results show that the language combination does not have any significant effect on response accuracy.

In order to understand whether the effect of language combination varies depending on the degree of difficulty of the items, we first compared the above model (m0) with a model including the level of difficulty of the items as a fixed effect (Level 1 and Level 2, based on the cluster analysis in Section 4.2.1). Then, we compared the resulting model (m1) with a model including the interaction between language combination and level of difficulty.Footnote 6 For both comparisons, we conducted a Likelihood Ratio Test, based on the anova-function in R (Winter, Reference Winter2013). The former model (m1) led to a significant improvement in fit to the data (χ2(1) = 790.75, p <.001) compared to the original model (m0). In contrast, the interaction between language combination and level of difficulty (in m2) did not provide any significant improvement in fit to the data compared to m1 (χ2(2) = 3.49, p = .17). This suggests that the effect of language combination is visible neither in association with the easiest structures nor in association with the most difficult structures.

5. Discussion and concluding remarks

The first result emerging from the present study is that children with Portuguese as HL do not exhibit difficulties with all items of the cloze-test to the same extent. In particular, the HCA analysis reported in Section 4.2.1 shows that the items cluster around two levels of difficulty. On the one hand, the level including the easiest structures features items targeting knowledge of regular nominal, verbal and adjectival inflection (e.g., flores ‘flowers’, olham ‘they observe’ or lindíssimo ‘most beautiful’, respectively), negation, the reflexive clitic and subordinate connectors introducing adverbial clauses (e.g., enquanto ‘since’ or porque ‘because’). On the other hand, the level including the most difficult structures features third-person clitics, the relative pronoun que, (contracted and non-contracted) prepositions and the inflected infinitive in concessive constructions (introduced by apesar de ‘although’). Previous literature shows that all these structures are challenging for monolingual children as well and usually emerge late (or very late) in monolingual acquisition of EP. For example, monolingual children acquiring EP master clitic pronouns fully only at school age (cf. Costa & Lobo, Reference Costa, Lobo, Baauw, Drijkoningen and Pinto2007; Costa et al., Reference Costa, Lobo and Silva2009; Flores et al., Reference Flores, Rinke and Sopata2020). Relative clauses are also among the latest types of subordinate clauses to appear in EP child speech (cf. Soares, Reference Soares2006; Vasconcelos, Reference Vasconcelos and Faria1991). The same is true for the concessive connector apesar de (Costa, Reference Costa2006). Therefore, the triangulation between the results of this study and the evidence drawn from studies on the acquisition of EP by monolingual children suggests that the learning process and outcomes of certain structures by Portuguese HL children varies depending on their timing in monolingual language acquisition (Schulz & Grimm, Reference Schulz and Grimm2019; Tsimpli, Reference Tsimpli2014; see also the discussion below related to age effects). In Rinke, Flores and Torregrossa (submitted), we proposed a theoretical account of the difficulty of these structures in monolingual and bilingual language acquisition in terms of four main factors, i.e., derivational complexity, memory-based lexical forms, rules dependent on phonological or discourse contexts and non-linear form-function mappings. For example, third-person clitics are complex not only because their use involves the integration of syntactic and discourse information (Flores et al., Reference Flores, Rinke and Sopata2020), but also because, in EP, clitics exhibit different allomorphic forms, i.e., the form of a clitic may change depending on the phonological context. Thus, in EP, the form of clitics is context-dependent and there is no linear form-function mapping in their use.

It should be noticed that in some specific cases, HL children reduced the complexity of the target structure. For example, in the contexts in which the target structure corresponded to the complementizer que ‘that’, the use of the overt pronoun ele ‘he’ would also be possible, but the subordinate clause would be converted into a main clause. This was, in fact, a frequent answer given by the children. The production of two main clauses instead of a main clause selecting a subordinate one leads to a reduction of layers of embedding and, hence, results in a reduction of derivational complexity, as has been noticed in other studies on HL speakers (see, e.g., Hopp, Putnam & Vosburg, Reference Hopp, Putnam and Vosburg2019; Polinsky & Scontras, Reference Polinsky and Scontras2019). Coming back to the parallelism between monolingual and HL acquisition, it may be the case that the same mechanisms of reduction of syntactic complexity occur in monolingual language acquisition too (see Jakubowicz & Strik, Reference Jakubowicz and Strik2008). Results from a pilot study with monolingual children who filled out the same cloze-test as the one used in this study indicate that this may be indeed the case. Given that the present study does not include a group of monolingual children, we leave this issue open for future research.

Turning to the role of language external variables in the production of accurate structures in the cloze-test, we found a significant effect of age, which emerges both from the correlational analysis reported in Table 3 (Section 4.2.2) and the lmer-analysis in Table 4 (Section 4.2.3). This suggests that increasing age leads to an improvement in language abilities, most likely because full mastery of certain linguistic structures requires children to achieve a certain degree of cognitive maturity. This provides further evidence in favor of the idea that the process of HL acquisition parallels the one of monolingual language acquisition. Some studies on HL acquisition have found that young heritage speakers tend to perform better or on the same level as older ones, mainly because the latter exhibit a shift in dominance from the HL to the SL (see, e.g., Armon-Lotem et al., Reference Armon-Lotem, Rose and Altman2021; Chondrogianni & Schwartz, Reference Chondrogianni and Schwartz2020). The results of this study show the opposite, in line with research that has found an effect of chronological age on HL acquisition (Rodina et al., Reference Rodina, Kupisch, Meir, Mitrofanova, Urek and Westergaard2020). This may be due to two main reasons. First, our study targets a range of structures of different difficulty. Children may only be able to acquire the most difficult structures at older ages (see references in Section 2.1). Second, the HL children analysed in this study may, in fact, have more contact with the HL than the HL speakers analysed in other studies. EP is the third most spoken language in Switzerland, with a strong community and an extended network of HL classes in all cantons (Flores, Gonçalves, Rinke & Torregrossa, Reference Flores, Gonçalves, Rinke and Torregrossa2022; Gonçalves & Vinzentin, Reference Gonçalves, Vinzentin, Souza and Melo-Pfeifer2021 and references in Section 2.3). This indicates that Portuguese is continuously present in the children's lives in many contexts of socialization, complemented by frequent trips to Portugal, as often indicated in the parental questionnaires. Thus, Portuguese HL speakers may be more balanced in terms of language dominance than, for instance, some groups of Russian or Spanish HL speakers in the US.Footnote 7 Recent research has shown that the size of the immigrant community may have a positive effect on the acquisition of a HL (see, e.g., Rodina et al., Reference Rodina, Kupisch, Meir, Mitrofanova, Urek and Westergaard2020). Children from larger immigrant communities are more proficient in the HL than children from smaller communities (or children who do not have contact with a HL community). In addition, all children in this study attended HL classes, which are also crucial for HL maintenance and acquisition (Caloi & Torregrossa, Reference Caloi and Torregrossa2021; Kupisch & Rothman, Reference Kupisch and Rothman2018; Rinke & Flores, Reference Rinke and Flores2014; Rinke et al., Reference Rinke, Flores, Santos, Gabriel, Grünke and Thiele2019; Rodina et al., Reference Rodina, Kupisch, Meir, Mitrofanova, Urek and Westergaard2020).

This study emphasizes the importance of exposure to formal instruction for HL acquisition. Overall, greater exposure to formal instruction leads to higher accuracy in the cloze-test. We found that exposure to formal instruction has a different effect depending on the level of difficulty of the target structures (see Figure 3). In association with the easiest structures, exposure to formal instruction serves to stabilize knowledge and may lead to performance at ceiling. With the most difficult structures, exposure to formal instruction activates the learning process and leads to a higher degree of mastery (see Section 4.2.3). As mentioned in Section 2.1, several studies have reported that HL proficiency benefits from explicit language instruction (Bowles & Torres, Reference Bowles, Torres, Montrul and Polinsky2021; Montrul & Bowles, Reference Montrul and Bowles2010; Rinke et al., Reference Rinke, Flores, Santos, Gabriel, Grünke and Thiele2019; Rodina et al., Reference Rodina, Kupisch, Meir, Mitrofanova, Urek and Westergaard2020). Contrary to our expectations, the lmer-analysis does not show any effect of other language exposure variables on children's response accuracy (see Section 4.2.3). It should not be disregarded that some of the most difficult structures for the HL children in this study are also fully mastered by monolingual children only at school age. Therefore, it is not excluded that literacy exposure plays a crucial role in the acquisition of these (difficult) structures among monolingual children too. In addition, it should be remembered that the relevant role played by exposure to formal instruction may be related to the nature of the task. Spelling errors notwithstanding (which were not considered to be errors in the analysis), successful performance in a cloze-test requires children to be able to read and comprehend a text, which are literacy-related abilities (see Section 2.2).

The present study does not show significant effects of language exposure variables on HL children's performance in the cloze-test, apart from a weak correlation between the accuracy score in the cloze-test and the number of persons speaking Portuguese to the child. Crucially, this result suggests that the variety (or richness) of language exposure affects HL acquisition positively, in line with what has been found in many other studies (e.g., Gollan et al., Reference Gollan, Starr and Ferreira2015 – see Section 2.1). This relates to the fact that in general, the Portuguese descendant children living in Switzerland interact with a number of different speakers of EP since EP is usually spoken by both parents (see also Desgrippes & Lambelet, Reference Desgrippes, Lambelet, Berthele and Lambelet2017 for a similar observation) and is present in the wider community of Portuguese migrants, as discussed above.

Neither SES nor L2 AoA predicted children's response accuracy in the cloze-test. The lack of any effect of SES may be related to the fact that the group of children considered in this study is quite homogeneous in terms of SES (see Table 2 and Desgrippes & Lambelet, Reference Desgrippes, Lambelet, Berthele and Lambelet2017). The results related to L2 AoA are in line with other studies mentioned in Section 2 (Armon-Lotem et al., Reference Armon-Lotem, Walters and Gagarina2011; Makrodimitris & Schulz, Reference Makrodimitris and Schulz2021).

In general, the present study suggests that HL competence benefits more from variables related to qualitative aspects (i.e., exposure to formal instruction and a rich variety in the input) than quantitative aspects (amount of Portuguese spoken at home or a later L2 AoA) of language exposure.

Finally, the lmer-analysis reported in Section 4.2.4 does not provide any evidence for cross-linguistic effects. We hypothesized that children's response accuracy might benefit from language proximity between the HL and the SL, especially in association with ‘difficult’ structures such as third-person clitics. French and Italian have clitic pronouns, whereas German does not. However, the performance of German–Portuguese children did not differ significantly from either the French–Portuguese or the Italian–Portuguese children. Nor did the French–Portuguese or the Italian–Portuguese children show any advantage in the correct production of the most difficult structures, such as clitics. Although we cannot draw any inference from the lack of any effect, we speculate that these results are in line with our previous consideration that the acquisition process exhibited by HL children is similar to the one exhibited by monolingual children. Language-internal considerations as related to the ‘difficulty’ of the target structures and their timing of acquisition among monolinguals seem to be more relevant than cross-linguistic effects in HL acquisition.

Overall, we have emphasized that the results of our study suggest more parallels than divergences between the process of monolingual and HL acquisition. Both are sensitive to the difficulty of the target structures. Furthermore, literacy exposure seems to play a crucial role in the acquisition of ‘difficult’ structures both among monolingual and HL children.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the teachers of the Camões, Institute of Cooperation and Language, I.P. for helping us with the data collection and Dr. Maria de Lurdes Santos Gonçalves for coordinating them and contributing to the data coding. We are really grateful to the children who took part to the study and their parents for their availability to fill out the questionnaires. Finally, we thank the two reviewers and the editor for their constructive comments on previous versions of the paper.

Supplementary Material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728922000438

Table S1. Table reporting the target structures of the cloze-test in Portuguese sorted by linguistic domain (nominal, verbal, prepositional, sentential)

Figure S1. Example of the cloze-test administered to the children

Table S2. Total number, mean and standard deviation (per child) for each type of answer provided in the cloze-test (correct, unexpected correct, incorrect, missing)

Figure S2. Mean of silhouette values across different numbers of clusters. This method was used to determine the optimal number of clusters in the cloze-test data based on response accuracy across items