Introduction

Cognition can be broadly defined as the mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses. There are dissociable cognitive functions that have been implicated across a range of mental health conditions. A wide range of mental health disorders are associated with poor working memory, impaired decision-making, and attentional impairments (Gould, Reference Gould2010; Grace, Reference Grace2016; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Rubinsztein, Michael, Rogers, Robbins, Paykel and Sahakian2001; Pironti et al., Reference Pironti, Lai, Müller, Dodds, Suckling, Bullmore and Sahakian2014; Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Everitt, Baldacchino, Blackshaw, Swainson, Wynne and Robbins1999a).

The profile of cognitive impairment is important for understanding the neurobiological changes that may underpin these conditions, however pragmatically they are vital in understanding how pathologies manifest themselves in the day-to-day activities of individuals. Abnormalities of decision-making have been researched in mental health conditions. For example, a stark example of this relationship is in gambling disorder (as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Version 5 [DSM-5] [American Psychiatric Association, 2013]): affected individuals repeatedly gamble, and make unwise decisions, despite negative consequences. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews have shown the differences in aspects of decision-making in gambling disorder documenting increased risk taking, impulsivity, and impaired judgment (Grant, Chamberlain, Schreiber, Odlaug, & Kim, Reference Grant, Chamberlain, Schreiber, Odlaug and Kim2011; Ioannidis, Hook, Wickham, Grant, & Chamberlain, Reference Ioannidis, Hook, Wickham, Grant and Chamberlain2019; Kertzman, Lidogoster, Aizer, Kotler, & Dannon, Reference Kertzman, Lidogoster, Aizer, Kotler and Dannon2011; Kräplin et al., Reference Kräplin, Dshemuchadse, Behrendt, Scherbaum, Goschke and Bühringer2014). These changes may not be as apparent in other conditions. A better understanding of how cognition is affected in mental health pathologies may assist in the assessment of possible risk, as impaired cognition may lead to adverse outcomes for themselves or those around them.

Risk taking and impaired decision-making can be objectively quantified using the Cambridge Gambling Task (CGT) (Brand, Labudda, & Markowitsch, Reference Brand, Labudda and Markowitsch2006; Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Owen, Middleton, Williams, Pickard, Sahakian and Robbins1999b; Yazdi et al., Reference Yazdi, Rumetshofer, Gnauer, Csillag, Rosenleitner and Kleiser2019), which is part of the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB) (Sahakian et al., Reference Sahakian, Morris, Evenden, Heald, Levy, Philpot and Robbins1988). The CGT has proven sensitive to impaired decision-making in groups of people with gambling disorder, v. groups of controls, with gamblers having a higher tendency to seek risk and prefer more immediate rewards (Kräplin et al., Reference Kräplin, Dshemuchadse, Behrendt, Scherbaum, Goschke and Bühringer2014). These changes are not specific only to gambling and can be potentially seen in other conditions. For example, use of the CGT in depressed patients have shown altered cognition with impaired reward processing of individuals (Halahakoon et al., Reference Halahakoon, Kieslich, O'Driscoll, Nair, Lewis and Roiser2020; Yazdi et al., Reference Yazdi, Rumetshofer, Gnauer, Csillag, Rosenleitner and Kleiser2019). Other studies have also shown decision-making changes in anxiety and ADHD (Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Rubinsztein, Michael, Rogers, Robbins, Paykel and Sahakian2001; Sørensen et al., Reference Sørensen, Sonuga-Barke, Eichele, van Wageningen, Wollschlaeger and Plessen2017; Tolomeo, Matthews, Steele, & Baldacchino, Reference Tolomeo, Matthews, Steele and Baldacchino2018).

Furthermore, studies have employed the CGT to understand the neural substrates involved in decision-making (Clark, Cools, & Robbins, Reference Clark, Cools and Robbins2004). For example, in patients with cortical lesions, damage to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex affected betting (irrespective of the odds of winning) on the CGT, whereas insula cortex lesions were associated with problems adjusting bets as a function of the odds of winning (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Bechara, Damasio, Aitken, Sahakian and Robbins2008; Clark, Manes, Antoun, Sahakian, & Robbins, Reference Clark, Manes, Antoun, Sahakian and Robbins2003). Both types of brain lesion were associated with significant abnormalities in probability judgment. Continued research on the relationship between mental health disorders and cognition may lead to a greater understanding of the neurocircuitry that is implicated in the manifestation of these conditions.

Importantly, the relative profiles of decision-making abnormalities across these and other mental health disorders have not been well-characterized. Therefore, our study used the CGT in a large cohort with a rich profile of mental health psychopathology, allowing comparison to be made in how decision-making varies across diseases. The aim of the study was to explore the profile of decision-making performance (as indexed by the CGT) across a range of mental health disorders compared to people without the given disorder of interest (hereafter referred to as controls). We hypothesized that the decision-making impairments will be present across different mental health conditions compared to controls and this would be most significant in individuals affected by gambling disorder.

Methods

Sample

572 young adults (aged 18–29 years) were enrolled from general community settings using community advertisements in the Minneapolis and Chicago metropolitan areas were enrolled. Participants must have gambled at least five times in the past year (i.e. a proxy for some level of impulsive behavior) and be able to be interviewed in person to be included. Exclusion criteria for this study were hearing or vision problems that made performing cognitive tasks difficult, and an inability to understand and consent to the study – as determined by the study team following interview of the participants. Comorbidities were permitted in the clinical groups, for example if a given individual had both depression and anxiety, they were included in the clinical data for both the ‘depression’ computation and the ‘anxiety’ computation. Participants were recruited via media advertisements. Each participant received a $50 gift card to an online store as compensation. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Chicago approved the study and the consent statement. After receiving a complete description of the study, participants provided written informed consent. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Assessments

Demographic variables, including age, biological sex at birth, self-reported gender, self-reported racial-ethnic identity, and highest level of education completed, were recorded for all participants. Subjects received an in-person psychiatric evaluation from a member of the research team trained in the administration of all the instruments employed, these were:

➢ The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Inventory (Sheehan et al., Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs, Weiller and Dunbar1998). This was used to screen for depression, generalized anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, panic disorder, alcohol use disorder, schizophrenia, obsessive–compulsive disorder, and substance use disorder.

➢ The Minnesota Impulsive Disorders Interview which screens for compulsive buying, kleptomania, trichotillomania, skin picking disorder, pyromania, intermittent explosive disorder, compulsive sexual behavior, and binge eating disorder (Chamberlain & Grant, Reference Chamberlain and Grant2018; Grant, Reference Grant2008).

➢ ADHD World Health Organization Screening Tool Part A (ASRS v1.1) (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Adler, Ames, Demler, Faraone, Hiripi and Walters2005), which screens for putative Adult ADHD diagnosis. For the ADHD definition, in keeping with standard recommendations (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Adler, Ames, Demler, Faraone, Hiripi and Walters2005), endorsement of at least four of six ADHD symptoms on the ASRS Part A was deemed indicative of this disorder.

➢ The Structured Clinical Interview for Gambling Disorder (SCI-GD) (Grant, Steinberg, Kim, Rounsaville, & Potenza, Reference Grant, Steinberg, Kim, Rounsaville and Potenza2004), which screens for a diagnosis of gambling disorder alongside the severity.

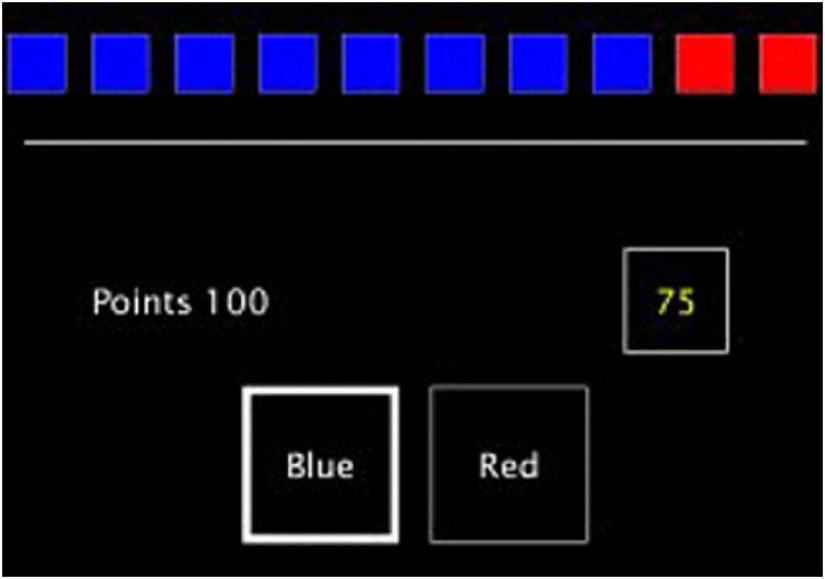

The CGT from the CANTAB (Sandberg, Reference Sandberg, Kreutzer, DeLuca and Caplan2011) was used to assess cognition of participants. The CGT was chosen as it is computerized, can fractionate distinct aspects of decision-making, and has received extensive investigations into its neurobiological underpinnings. In this assessment task ten blue and/or red boxes are presented in varying ratios (e.g. 7:3. 6:4) on a touch-sensitive computer screen. Participants then decide whether the yellow token is hidden in a red or blue box, staking a proportion of their cumulative points on their choice being correct. The proportions shown are 5, 25, 50, 75 or 95% randomly displayed in either descending or ascending order. If their choice was correct the stake is added to their total accrued points, or subtracted (i.e. lost) if incorrect. Participants are told that they should try and gain as many points as possible. Thus, the task explores different aspects of decision-making under controlled laboratory conditions (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Image of the CGT © Copyright 2018 Cambridge Cognition Limited. All rights reserved.

Three decision-making parameters were then recorded: the overall proportion of the bet, risk adjustment and the quality of decision-making. The overall proportion of the bet was the average proportion of points that was staked across the whole of the task. Risk adjustment was the degree to which a subject changed their risk taking in response to the ratios of red to blue boxes on each trial. Consistent riskier betting would lead to a lower risk adjustment score. A high risk adjustment score indicated a tendency to bet more in the rounds with better odds (Deakin, Aitken, Robbins, & Sahakian, Reference Deakin, Aitken, Robbins and Sahakian2004). Lastly, the quality of decision-making was the mean proportion of rounds where the most probable color (i.e. logical color choice) was chosen.

Data analysis

Only psychiatric disorders endorsed by at least 1% (5 or more) of participants were included in the data analysis. To assess the degree of impairment as quantified using the CGT, results were calculated into relative z-scores (effect size) v. controls. For each disorder of interest, controls comprised everyone in the total sample who did not have that disorder. For example, the control group for depression consisted of all participants that did not have depression as assessed by our instruments. Individuals that had comorbidities were included in the clinical data of all assessed conditions. For instance, an individual with anxiety and depression was included in the Z-score computation for both anxiety and depression. The effect sizes were interpreted per convention using Cohen's D criteria, with 0.2 being regarded as small/mild, 0.5 being moderate, and lastly 0.8 being large. Scores represented the proportion of participants either below or above the average of the control group (Fig. 1).

Results

The sample consisted of 572 participants, 65.7% were female and 34.3% male. The average age was 22.3 years old, with the majority (73.6%) having college education or higher. 72.1% were white Caucasian, 14.6% were African-American, and 6.3% were Asian. The remaining 7% consisted of Latino/Hispanic, Middle Eastern, Native American and mixed race. Table 1 shows the number of participants with each disorder.

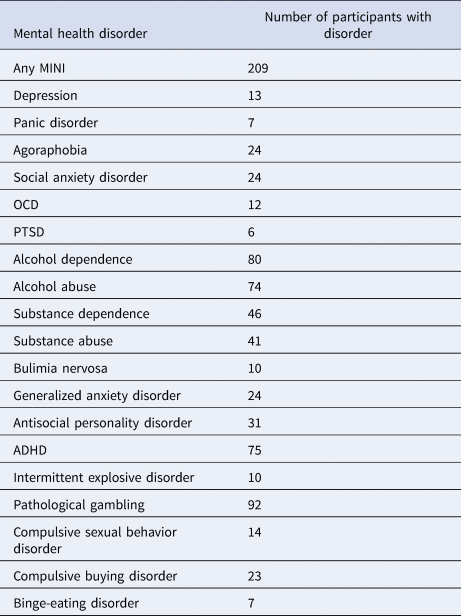

Table 1. Number of participants with each mental health disorder

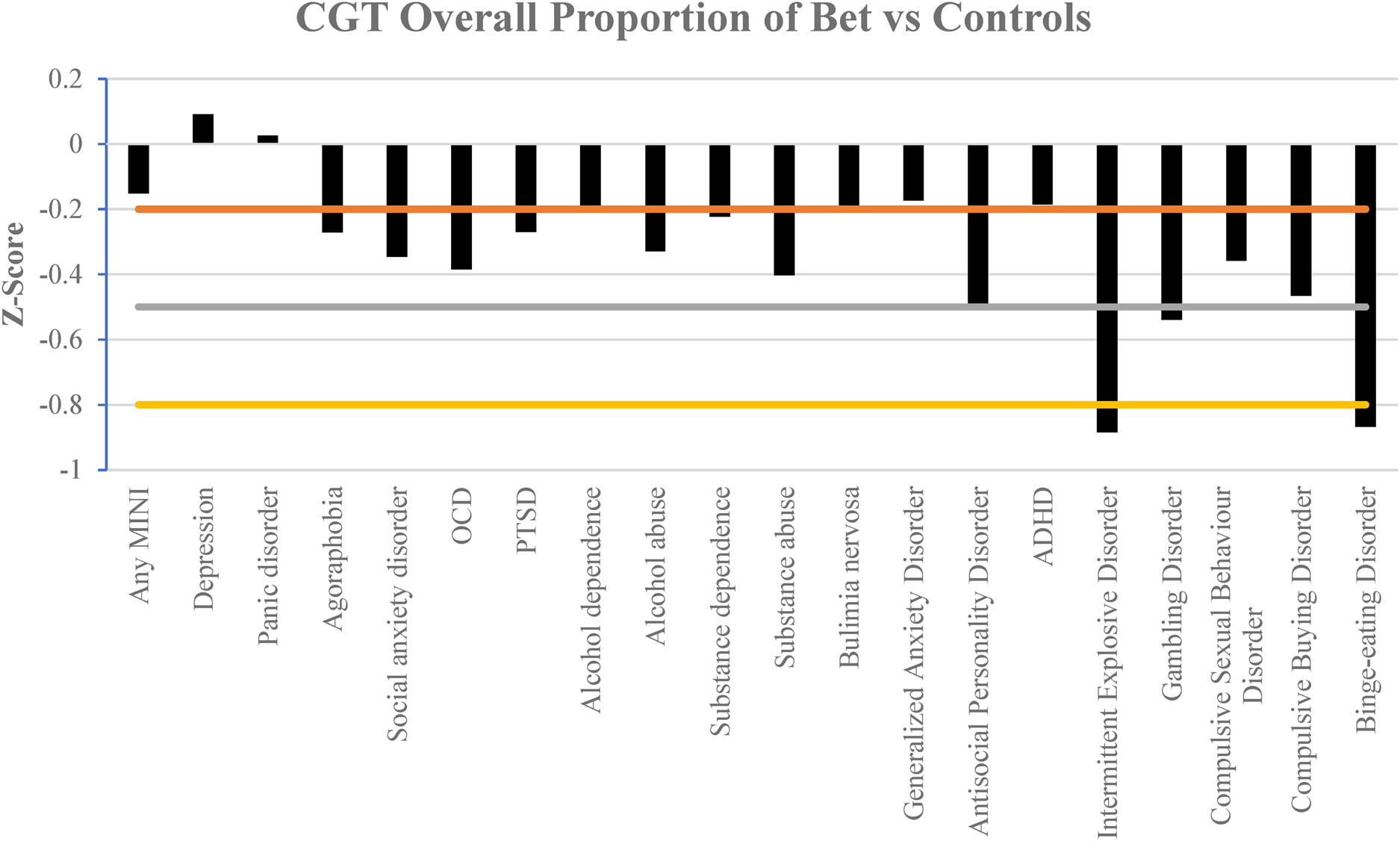

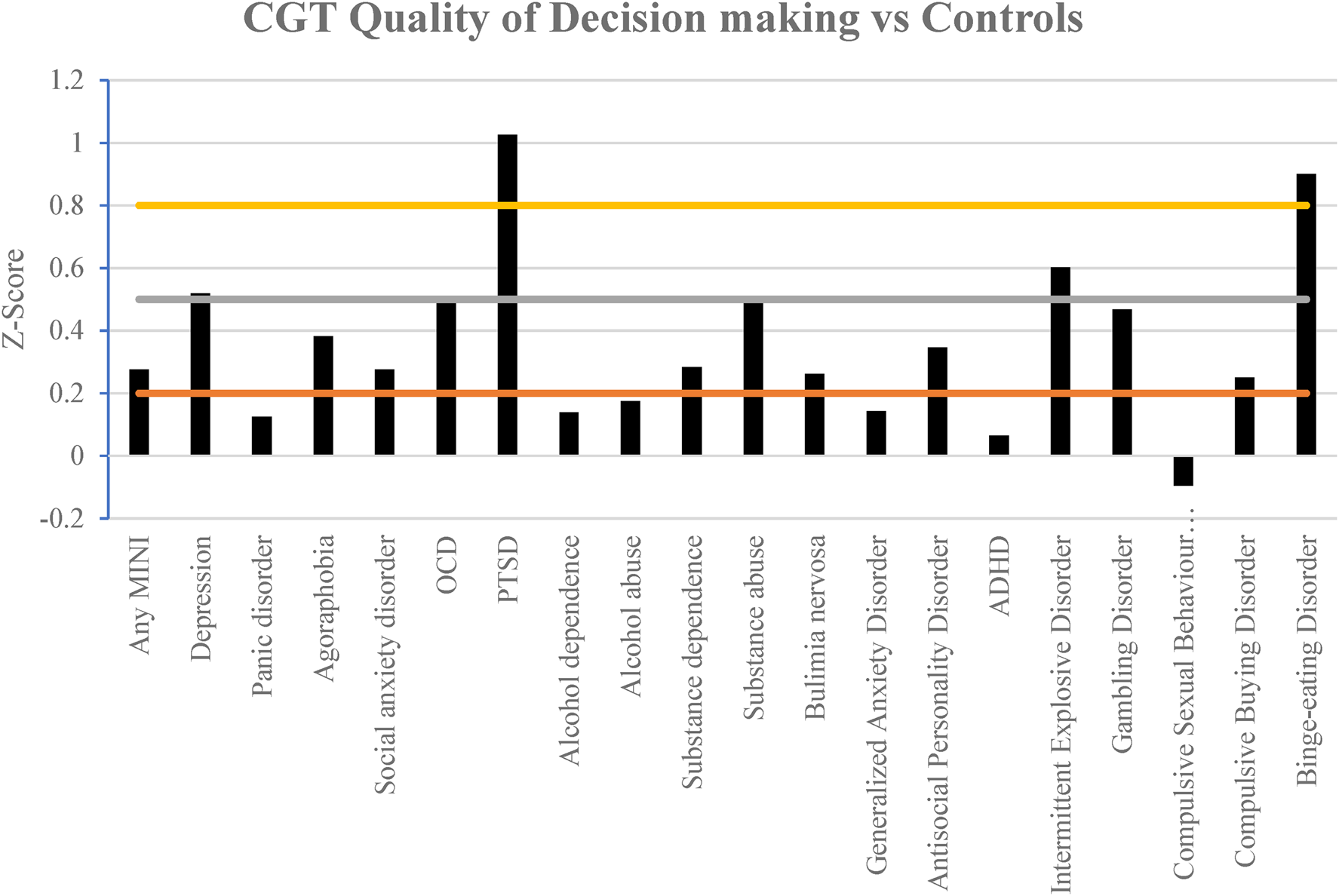

Figures 2–4 illustrate the results of the three different parameters as assessed via the CGT. Almost all mental health disorders were associated with at least a mild impairment in all parameters, as compared to respective control groups of individuals without the given condition.

Figure 2. Comparison of the effect size in the overall proportion of bet staked in the CGT in different mental health disorders compared against controls. Horizontal lines indicate magnitude of impairment, mild (−0.2), moderate (−0.5) and large (−0.8 and less). A more negative z-score indicates larger bets v. controls.

Figure 3. Comparison of the effect size in the quality of decision-making assessed via the CGT in different mental health disorders compared against controls. Horizontal lines indicate the magnitude of impairment, mild (0.2), moderate (0.5) and large (0.8 and greater). A more positive z-score indicates greater relative impairment v. controls.

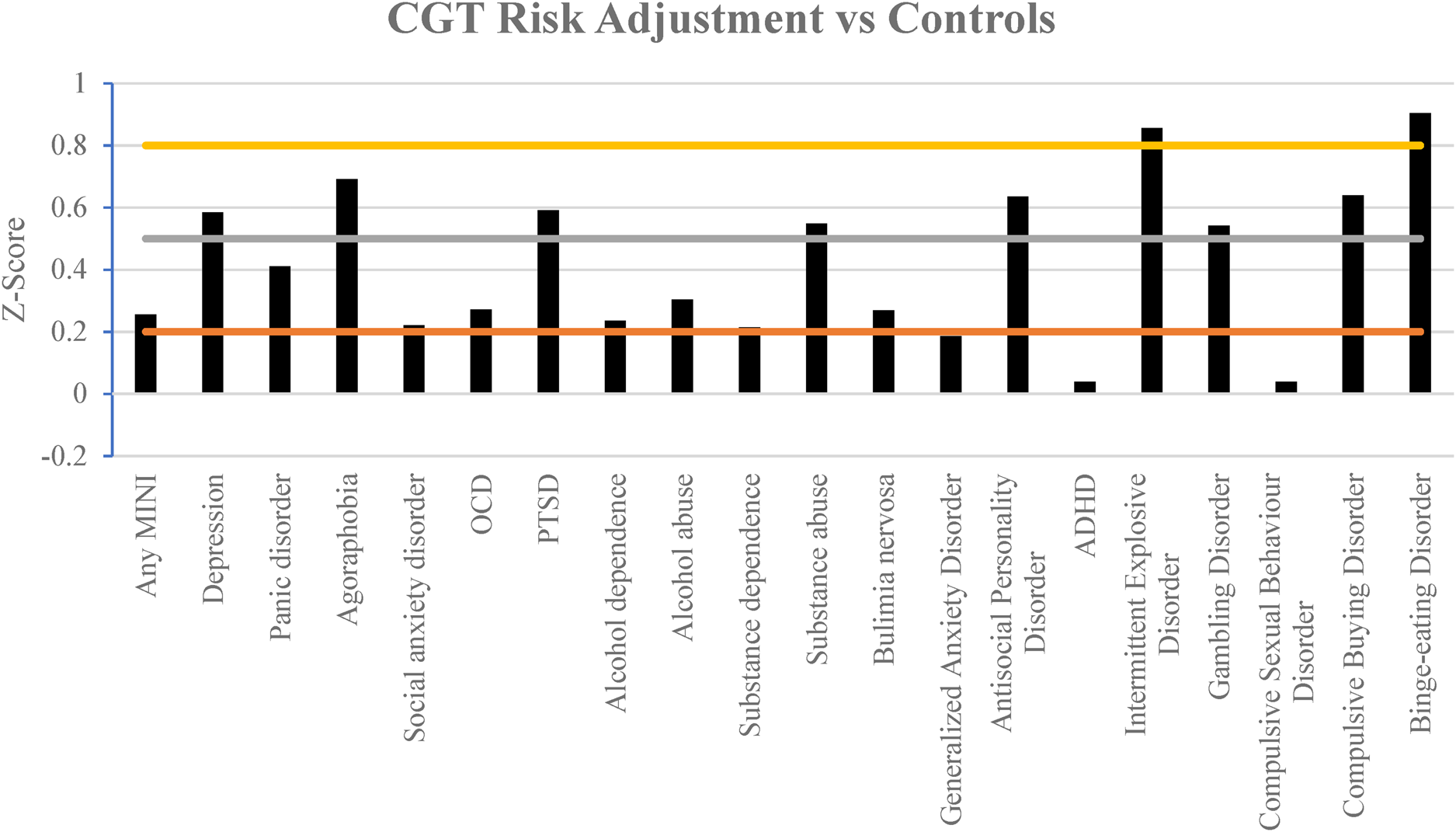

Figure 4. Comparison of the effect size in the adjustment of risk assessed via the CGT in different mental health disorders compared against controls. Horizontal lines indicate the magnitude of impairment, mild (0.2), moderate (0.5) and large (0.8 and greater). A more positive z-score indicates greater relative impairment v. controls.

Interestingly gambling disorder was associated with moderate impairment consistently in all three parameters, whereas binge eating disorder had large impairment throughout. Participants with intermittent explosive disorder also had a large tendency to bet larger proportions of their points and exhibited large impairment in risk adjustment.

Participants with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) had greater impairment in the quality of decision-making, whilst participants with major depressive disorder and obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) exhibited moderately impaired quality of decision-making (Fig. 3).

Participants' ability to manage risk and adapt was moderately impaired in half of the mental health disorders assessed. In contrast only ADHD and compulsive sexual behavior disorder failed to show at least a mild impairment on this domain (Fig. 4).

Discussion

This study is one of the first to report on the relative profiles of decision-making impairments across a broad range of mental disorders, using a laboratory-based paradigm. The key findings were that almost all disorders were linked to at least mild (i.e. small effect size) impairment in one or more decision-making measures. Some disorders were more profoundly affected than others, as described in detail below.

These results importantly highlight that decision-making was impaired – in relative terms – across different conditions, and contrary to our expectation while gambling disorder was linked to deficits, some other disorders had more profound impairments. Notably, binge eating disorder had larger cognitive impairment in comparison to all other psychiatric disorders, whereas in contrast gambling disorder had a moderate impairment throughout. The fact that decision-making was particularly impaired in binge-eating is interesting in light of a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of the available literature (Colton, Wilson, Chong, & Verdejo-Garcia, Reference Colton, Wilson, Chong and Verdejo-Garcia2023) – which found a range of impairments, across tasks and measures, relating to aspects of decision-making in binge-eating disorder. The authors suggested that the deficits could arise from a combination of processes, such as: difficulty forming stable preferences in situations involving ambiguous or complex outcomes; attentional response disinhibition; inflexibility; and difficulties using moment-by-moment feedback to optimize decisions (Colton et al., Reference Colton, Wilson, Chong and Verdejo-Garcia2023). Thus, these processes (or a combination of them) may have contributed to the particularly pronounced deficits seen in the current study, though future work would be needed to confirm this.

Those with intermittent explosive disorder were also the only participants that had a large effect size tendency to make larger bets, with poorer risk adjustment. As one would expect, those with gambling disorder also bet more which is consistent with the known psychological profile of the disorder (Ioannidis et al., Reference Ioannidis, Hook, Wickham, Grant and Chamberlain2019).

Participants with PTSD had large impairment in their quality of decision-making which was an interesting result. This may be due to a reduced expectation of a positive outcome as seen in a similar study assessing reward processing in PTSD (Hopper et al., Reference Hopper, Pitman, Su, Heyman, Lasko, Macklin and Elman2008; May & Wisco, Reference May and Wisco2020). Therefore, this may have led to participants believing the majority color was not as favorable due to a perception that regardless of their actions the rewards would be minimal (i.e. an ‘assumption of defeat’).

Most importantly, half of the mental health disorders assessed in this study showed a moderate to large impairment in risk adjustment, manifesting as a relative inability to flexibly adjust gambling behavior as a function of risk. However, it is unclear whether this is due to a tendency to engage in risky behavior. Two different strains of thought may be implicated in this result. Either the individual had a psychiatric disorder that caused them to be more risk averse, less pursuant in reward, and thus more rigid in their thinking e.g. PTSD, depression (Halahakoon et al., Reference Halahakoon, Kieslich, O'Driscoll, Nair, Lewis and Roiser2020; May & Wisco, Reference May and Wisco2020). Or alternatively the individual had a condition that is more risk prone such as gambling disorder (Kräplin et al., Reference Kräplin, Dshemuchadse, Behrendt, Scherbaum, Goschke and Bühringer2014). Therefore, they would be less likely to alter their risky behavior in pursuit of higher gains because their overall profile of approach was to take higher risks.

These results suggest that mental health conditions not conventionally studied/conceptualized in terms of cognition may nonetheless have complex psychological profiles that include a degree of relative decision-making impairment. A better understanding of such impairment may allow for clinical treatment to better assess the risk that could be involved with these disorders. A holistic appreciation of the psychological profile may allow clinicians to better understand behavior and the subsequent choices patients may make and work towards better outcomes. For example, cognitive training is being explored as a candidate intervention for gambling disorder (Luquiens, Miranda, Benyamina, Carré, & Aubin, Reference Luquiens, Miranda, Benyamina, Carré and Aubin2019). Because some degree of deficit (in relative terms) was found across disorders, impaired decision-making may not be specific to any disorder, but could be viewed as a trans-diagnostic treatment target, and possibly an indication of vulnerability. Relatedly, the overlapping deficits may reflect overlapping comorbidities across disorders.

Limitations

Despite examining decision-making profiles across disorders, it is important to consider a number of limitations. Firstly, it is important to note that the CGT examines aspects of decision-making and is not designed to fully capture ‘impulsivity’ – especially in terms of disinhibition, which is better measured using tasks such as stop-signal paradigms. As a naturalistic study comparing people with v. without each mental health condition of interest, cognitive findings could have been contributed to by other variables (such as comorbidities, or demographic differences between groups). Some of the disorders studied had relatively small sample sizes, and it will be important to attempt to replicate findings using larger samples in future. The sample's average age was 22.4 years old, being majority female, which may reduce the generalizability of the data (Rolison, Hanoch, Wood, & Liu, Reference Rolison, Hanoch, Wood and Liu2014). Some research has shown that age and gender can influence CGT performance to some degree (Deakin et al., Reference Deakin, Aitken, Robbins and Sahakian2004; Rolison et al., Reference Rolison, Hanoch, Wood and Liu2014). Future work should address the influence of age and gender, and other potential confounding variables (e.g. comorbidities), but this would require a larger sample than was available here. The participants in this sample were non-treatment seeking which could reduce the applicability of the findings to people presenting in clinical settings. In addition, we were unable to control for co-morbidities or the use of medications or drugs that affect cognition due to the small sample size and the nature of the study. As comorbidities are common in mental health conditions it is likely that some participants had more than one disorder. Another limitation is that we focused on effect sizes, due to the variable and in some cases relatively small sample sizes in particular groups, rather than conducting formal statistical p values tests. Some of the disorders studied had relatively small sample sizes, and it will be important to attempt to replicate findings using larger samples in future. Lastly, as a cross sectional study, these results cannot determine causality between mental health disorders and cognition. Addressing this issue would require a very large-scale longitudinal study with inclusion of detailed screening for such a broad range of mental disorders, including gambling disorder (which is often overlooked).

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study presented the relative decision-making profiles of people with a range of mental health disorders, using a computerized laboratory-based task. The findings highlight the need to consider decision-making not only in conditions conventionally likely to be linked to impairments, such as gambling disorder, but also other conditions such as PTSD and binge-eating disorder. If these findings generalize to people with these conditions, the relative cognitive deficits may constitute trans-diagnostic targets for treatment interventions, or indicate the need to adapt existing treatments in order to help address these additional difficulties.

Author contributions

RE led on analysis of the data and writing of the report. JG designed the study and collected the data. SRC, JG, and KI provided input into the analytical approach, writing of the manuscript and interpretation of the findings. All authors take joint responsibility for integrity of the data.

Funding statement

This research was funded by the National Center for Responsible Gaming (NCRG) Center of Excellence grant (JEG).

Competing interests

SRC and KI receive a stipend from Elsevier for journal editorial work. JG has received research grants from Janssen and Biohaven Pharmaceuticals. He receives yearly compensation from Springer Publishing for acting as Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Gambling Studies and has received royalties from Oxford University Press, American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc., Norton Press, and McGraw Hill. RE has no disclosures.