1 Introduction

The “Great Divergence,” in which Western Europe industrially outpaced the rest of the world by the early 19th century, has puzzled scholars for centuries. Recent studies tracing its origins increasingly point to a deeper, underlying political divergence that may have begun much earlier (Cox, Reference Cox2017; Dincecco and Wang, Reference Dincecco and Wang2018; Stasavage, Reference Stasavage2020; Huang and Yang, Reference Huang and Yang2022; Fernández-Villaverde et al., Reference Fernández-Villaverde, Koyama, Lin and Sng2023; Chen, Wang, and Zhang, Reference Chen, Wang and Zhang2025). Central to this political divergence is the role of institutions, such as European parliaments. These parliaments limited the power of rulers through checks and balances, while the resulting credible commitments fostered political stability to a degree far greater than what was seen in many other parts of the world (Blaydes and Chaney, Reference Blaydes and Chaney2013).

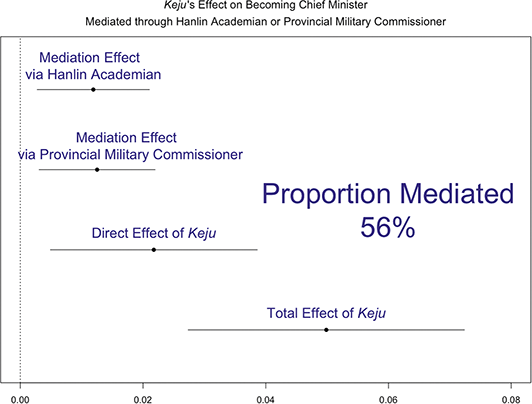

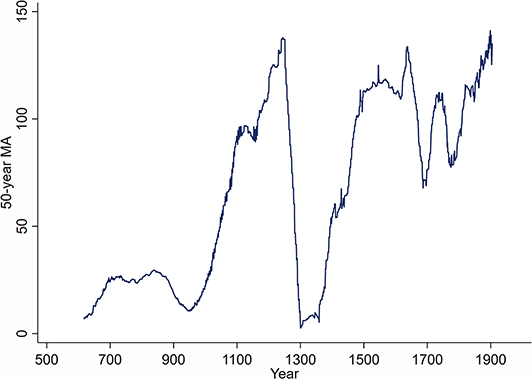

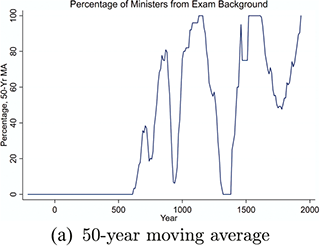

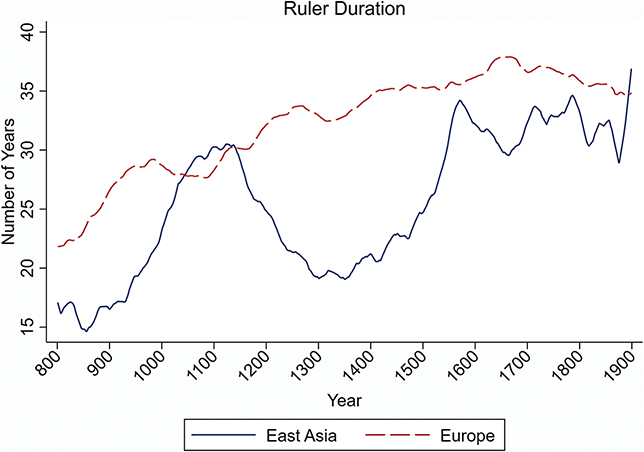

We argue in this Element that an important parallel institutional development in East Asia was the Imperial Civil Service Examination System, hereafter referred to as Keju (科举). Keju served as a method of recruiting officials for the imperial government through a standardized written test on Confucian classics and literature – a test that was open to most males. Emerging sometime between 587 and 622 ce and lasting until 1905 ce, Keju was not only an outcome of political development but also a potential contributor to the political divergence that set the East and West on different historical paths. Crucially, Keju enabled Chinese monarchs to maintain political stability comparable to that of their European counterparts, without the need for concessions resembling parliamentary constraints (Figure 13 and Table 2).

1.1 Twin Arguments

This Element makes two arguments regarding the link between Keju and long-run political development.

Argument 1

Keju contributed to stability and the consolidation of absolutism by fulfilling a political function. By evaluating candidates based on exam performance rather than family background or social status, and with its inclusiveness toward most males, Keju expanded political access to a broader segment of the population and promoted upward mobility.

Borrowing terminologies from the “selectorate” theory in De Mesquita et al. (Reference Mesquita, Bueno, Smith, Siverson and Morrow2005), Keju essentially expanded the selectorate. By increasing the pool of eligible candidates for office, Keju rendered each member of the monarch’s “inner circle” more replaceable and, consequently, more reliant on the monarch (Huang and Yang, Reference Huang and Yang2022). We demonstrate with extensive evidence in the following sections that this political function withstood the test of time with a surprising level of resilience. The magnitude of aristocratic advantage continued to decline, and the level of social mobility within the broader elite continued to rise over time. Moreover, leveraging a cross-country panel dataset, we show that the Keju was associated with an increase in ruler stability that was comparable to the impact of parliaments in Europe.

Keju was “proto-meritocratic.” It had the aforementioned meritocratic tendencies, but the meritocracy was only “proto” because it primarily equalized opportunities within the broader elite, as many commoners were not wealthy enough to afford the books and time (away from agriculture) to prepare for the exams.Footnote 1 The term “proto” suggests a continuum, indicating that the system’s capacity to equalize opportunities could either increase or decrease. Sections 3 and 4 detail efforts made by rulers to maintain Keju’s equalizing potential. These efforts included ad hoc but consistently applied affirmative actions against the powerful families during the 9th century, the narrowing of the curriculum and the standardization of exam format, and the expansion of the school system over the second millennium.

Keju was also proto-meritocratic because the exams might not test people’s “true” competence. There was a considerable gap between what was being tested and the skills necessary for effective administration or statecraft. Candidates usually succeeded by writing highly formulaic and predictable answers within a predominantly Confucian framework. We clarify, however, in Section 5.2.4 that selection based on true competence is not a precondition for Argument 1 to hold. There could even be a potential trade-off between the equalizing dimension and the competence dimension of meritocracy: a hypothetically perfect device to identify “true” talents could quite possibly end up selecting the political know-hows, who would have predominantly come from families with officeholding traditions. History seems to suggest that, at times, the emperors were willing to sacrifice talent in favor of the equalizing effect.

Argument 2

However, it’s crucial not to conflate the “effect” of an institution with its “origins” (Pierson, Reference Pierson2004). The long-term political consequences of Keju could hardly have been foreseen by powerholders in the late 6th and early 7th centuries when the system first took shape. Even though one of Keju’s key political consequences was to enhance the ruler’s power vis-à-vis the upper elites, it is unlikely that the “designer” of Keju, if there was one to speak of, had this purpose in mind. And even if he did, Keju would not be able to achieve this goal until a century later. The Keju system, originating from gradual institutional change over the long durée since the 2nd-century ce, evolved in a context where events that now appear as “breakthroughs” were merely incremental steps at their time. The eventual development in 622 ce, which endowed the system with the potential to expand political access, emerged as a contingent response to urgent issues at the time, revealing a functional logic rather than a deliberate political strategy. Given the gradual nature of Keju’s development, its initial impact was minimal and difficult to discern, thus encountering little resistance. Over time, as its significance grew and in conjunction with unforeseen political developments, both the ruler and the elites came to view the institution as beneficial to their interests, thereby making Keju a self-enforcing institution. The emergence of Keju was a process, not a shock.

By treating Keju as both an outcome and a contributor to political development, and focusing on the positive feedback for the participants in the institution, our work borrows insights from the literature on historical institutionalism (Mahoney and Thelen, Reference Mahoney, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2009). This Element presents the evolution of bureaucratic selection in imperial China as an excellent example of gradual institutional change over the very long run, in which Keju itself had attained at least 1,200 years of prominence. This process saw changes take place incrementally as rulers and elites responded to unforeseen and exogenous events.

1.2 Keju versus Parliament

A new scholarship in historical political economy now distinguishes between an institution’s consequences from its origins, though much of this literature chiefly concerns with representative institutions. Recent studies demonstrate that the ruler-constraining and mass empowerment functions of modern parliaments differed from the purpose of their emergence, which was to collect information and assist governance for the ruler (Stasavage, Reference Stasavage2020; Boucoyannis, Reference Boucoyannis2021). Boucoyannis (Reference Boucoyannis2021), in particular, shows how national parliaments were initially judicial institutions employed by rulers to extend control over the population and territory. Its original purpose was not to constrain the crown, a completely opposite political function that only materialized much later. Similarly (and conversely), it was also unlikely that Keju was “invented” to undermine the aristocracy (Sections 2 and 3), a consequence that took almost a century to materialize.

Another similarity is that sufficient ruler strength is required for the consolidation of both institutions. In the European case, nobles initially resented the heavy burden of serving their judicial duties in the parliament for the ruler. The national parliament was successful in England because ruler strength there was the highest across European polities and enough to achieve “elite compellence” (Boucoyannis, Reference Boucoyannis2021). The Chinese emperor was even more powerful than the English monarch in the following sense. The upper elites in imperial Chinese history, for the most part, had to operate within a bureaucratic framework and derive their power, prestige, and, to some extent, wealth from bureaucratic performance, the ultimate evaluator of which was the ruler herself. It was in this context, as Section 3 documents, that the elites’ pursuit of their own political benefit furthered their alignment with the Keju. Despite the similarly contingent origins, European parliaments would eventually become ruler-constraining and facilitate credible commitment to underpin high state capacity (Dincecco, Reference Dincecco2017). In contrast, Keju’s long-term consequence was to further empower an already powerful monarchy, the absolutism of which eventually inhibited state development (Wang, Reference Wang2022).

1.3 Organization of the Element

We substantiate our arguments by analyzing a diverse array of quantitative data and qualitative evidence, drawing on both primary materials and secondary literature. As this research studies a historical institution, we organize the sections in a semi-chronological order. We start with Argument 2 in Sections 2 and 3 and end with Argument 1 in Section 5, while the second half of Section 3 and most of Section 4 substantiate both arguments.

To give readers unfamiliar with Chinese history a concise context before exploring the detailed analysis of long-term institutional evolution, we include the following brief historical overview of the Keju system.

1.4 Brief Historical Overview

Before the consolidation of Keju, China’s bureaucratic selection limited candidacy either formally or informally to a select few. The “Chaju” system, initiated in the 2nd-century bce, involved local officials nominating individuals for entry into the bureaucracy via examination. The Nine-Rank Rectifying System (NRRS), dominant from the 3rd to 5th centuries, categorized men into different grades based on their virtue and pedigree, with entry into the bureaucracy largely reserved for those with high grades.

Keju began to take shape during the Sui dynasty (581–618 ce) as an outgrowth of previous recruitment methods, still restricting participation to those nominated by government officials. However, in 622 ce during the Tang dynasty (618–907 ce), the exam was opened to most men and continued to mature throughout the 7th–9th centuries.

The Song dynasty (960–1279 ce) refined the system by institutionalizing multiple levels of exams and strictly enforcing regional quotas. Participation further broadened at the societal level with the state’s commitment to promoting broader education and advancements in printing technology. The Ming and Qing Dynasties (1368–1911 ce) further refined the Keju with more rigorous qualification exams and the widespread establishment of public schools to standardize preparation.

The system was abolished in 1905 as the Qing dynasty faced internal and external pressures, including modernization demands and Western colonialism.

2 The Origins

2.1 Motivation

The core of this Element begins in the year 622 ce, when a significant institutional change seemed to have happened to the Keju. By then, what would later be recognized as the Keju system had been in its nascent stage for approximately two to three decades, albeit participation in the examination was limited to individuals nominated by senior government officials. Now, with an imperial edict by Emperor Gaozu of the Tang dynasty (唐高祖), the examination had been made open to the majority of adult males. From the perspectives of social science grand narratives, this was a monumental development. It essentially represented a “selectorate expansion” (Huang and Yang, Reference Huang and Yang2022). By enlarging the pool of potential bureaucratic candidates, the ruler increased his leverage over the existing elite, making them more reliant upon him (De Mesquita et al., Reference Mesquita, Bueno, Smith, Siverson and Morrow2005). Relatedly, it’s also tempting to view this policy as a deliberate move to promote social mobility, a key contributor to political stability as theoretical work of authoritarian politics would have us believe (Leventoğlu, Reference Leventoğlu2005; Jia, Roland, and Xie, Reference Jia, Roland and Xie2023).

Intriguingly, what should have marked a paradigm shift in the politics of the then world’s largest empire largely escaped mention in its standard histories. The paramount texts for the political history of the Tang dynasty, where this pivotal change occurred, are the Old Book of Tang (《旧唐书》), New Book of Tang (《新唐书》), and Comprehensive Mirror in Aid of Governance (《资治通鉴》). These texts meticulously document many significant policy shifts of the dynasty, but this particular transition is conspicuously absent.Footnote 2

More intriguingly, not a single historical source from the Tang makes mention of resistance or even debate regarding this policy. This notable silence stands in stark contrast to the grand narratives presented in social sciences about the Keju. For instance, a recent publication, specifically attributing the Keju as the primary cause of the “Great Divergence” between China and the West, describes this reform as possessing a transformative potential that “few actions in human history can match” (Huang, Reference Huang2023, p.43).Footnote 3 The same book also posits that this shift in policy was a calculated move to “disrupt, weaken, and decimate the incumbent aristocratic class” (p. 41). If there were indeed a single class so powerful as to be “incumbent,” why didn’t its members resist, or at least voice some complaints, about this dramatic shock?

Of course, we should not automatically equate the lack of recorded activities, be it discussions, debates, or resistance, with the lack of activities. It’s possible that any resistance or dissent from the aristocrats was omitted or erased from the records. Another possibility is that the records from the Tang are simply scarce, given that the event of interest transpired over 1,400 years ago. Naturally, the farther back we look, the fewer records remain. However, both scenarios are unlikely. The chief compilers of neither Old Book of Tang nor New Book of Tang were “aristocrats” by Tang standards. If anything, they were emblematic of the new elite that emerged from the 10th century onwards through Keju, long after the influence of the Tang dynasty aristocracy had already waned (Lu, Reference Yang2016; Wen, Wang, and Hout, Reference Fangqi, Wang and Hout2024). The author of Comprehensive Mirror was in the same category. For the argument’s sake, suppose that the purpose of manipulating history here was to protect the reputation of the “villains” in this event, the Tang aristocrats. Then post-Tang new elites would be the last one to do so. Had there been any dissenting views voiced by the aristocrats in 622 ce, the chroniclers of Tang history would be the least likely to hide them in protection of the aristocrats’ reputation. Indeed, 11th-century writers, like the authors of Comprehensive Mirror and New Book of Tang, were actually quite keen on casting aristocrats in a negative light.Footnote 4 Equally importantly, critiques of Keju are actually quite prevalent across historical records covering the Tang, so it is also unlikely that the absence of recorded debate suggests that the later compilers, despite their ascension through this system, intended to deflect criticisms about Keju.

More generally speaking, the Chinese historiography is not at all shy of recording the details of policy change, or the vigorous controversies, debates, and objections that might follow suit. A casual reader of imperial Chinese history could immediately think of the Wang Anshi Reform (王安石变法) in the mid-11th century, the “Single Whip” Reform (一条鞭法), and the submersion of the poll tax within the land tax (摊丁入亩) in early 18th century, all of which met fierce resistance from the vested interests.Footnote 5 Even prior to the Tang dynasty, when historical records were scarcer, there are detailed discussions of reforms that challenged the established powerholders, such as the Monopoly over Salt and Iron in the late 2nd-century bce (Wagner, Reference Wagner2001) and the state-building reform in the late 5th century that laid the foundation for the country’s reunification later on (Chen, Wang, and Zhang, Reference Chen, Wang and Zhang2025).

The Tang dynasty where the selectorate expansion via Keju happened was an era of great transformation. Numerous policies instituting profound changes were enacted in the dynasty. Some of them, such as the “Two-Tax Reform” (两税法) of 780 ce and the reform of 819 ce that divided military authority in the provinces, have recently been subjects of quantitative political science research (Wang, Reference Wang2022; Chen and Wang, Reference Chen and Wang2024). The former, in particular, was highly controversial and intense debates and critiques have been well-documented in the records.Footnote 6 The latter, while itself not causing much controversy, was set in motion in a larger context where the Tang rulers became increasingly intolerant of rebellious military commissioners in the provinces (Chen and Wang, Reference Chen and Wang2024). Debates and conflicts between the “doves” and “hawks” toward the provinces were on full display from the historical records.Footnote 7

Given the depth of Chinese historiography on policy reforms, the silence on the 622 ce Keju change is revealing. Perhaps the most logical interpretation is that the resistance from the powerholders, in this case the aristocrats, was indeed negligible. The lack of opposition or even discussion is puzzling in hindsight. Both the evidence in Sections 3 and 4 and the works by others reviewed in this Element, including Huang (Reference Huang2023), suggest that Keju would go on to have a profound impact. However, from the eyes of the early 7th-century beholders, such as the Tang aristocrats and even the emperor himself, it might not appear as if anything transformative had happened. The imperial edict in 622 ce, as we argue, was simply an incremental step in the longue durée of gradual institutional change over the course of medieval Chinese history. Rather than a jolting change, it might well have been perceived as a continuation of past developments, thus not triggering vigorous discussion, let alone fierce opposition.

The rest of this section and Section 3 explain the origins and early development of Keju. This section documents the gradual institutional evolution of China’s bureaucratic selection system prior to the 7th century. Section 3 addresses the evolution of Keju in the second half of the 7th century, focusing on the rising importance of this institution under Empress Wu. It then employs both quantitative and qualitative evidence to show how Keju eventually became a self-reinforcing institution in which both the ruler and the elites saw benefits from participating. These sections integrate insights from historical institutionalism (e.g. Mahoney, Thelen et al., Reference Mahoney, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2009) to focus on institutional layering and positive feedback that made Keju eventually self-reinforcing. A key takeaway from this section is that institutional changes that are ex post transformative like the Keju should often be understood as a process, not a shock. This understanding is also in line with recent findings on the emergence of European parliaments (Boucoyannis, Reference Boucoyannis2021).

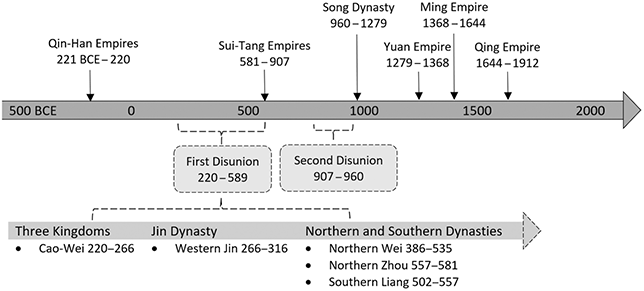

As this Element, especially in this section, extensively mentions numerous polities in Chinese history, Figure 1 presents a timeline featuring the relevant regimes.

Figure 1 Timeline of regimes studied in the Element

2.2 Gradual Institutional Change Over the Long Durée (The 2nd-Century bce to 622 ce)

We begin by examining the historical evolution of methods and institutions for bureaucratic selection prior to the Keju. The narrative focuses on two primary methods: one based on exams, though participation was limited to a select few; and the other based on pedigree, with those assessing pedigree also belonging to a privileged group. Chronologically, the latter method was layered on top of the former, although the exam-based approach was never completely crowded out. In the 6th century, however, there was a reversal of fortune between the two methods. The exam-based approach began to rise again, with the emergence of Keju viewed as an outgrowth of this revival.

Throughout this long durée of institutional change, it is undeniable that rulers were concerned about political selection coming under the control of a small group of privileged elites. However, our account emphasizes other, more functionalist factors, such as the need to reassert central government authority over localities and to recruit talent in the absence of reliable information. These factors were arguably more pivotal to the eventual emergence of Keju, which, in any case, was unlikely viewed by contemporaries as a transformative strategy by the ruler to undermine the aristocracy.

2.2.1 Han Dynasty (202 bce to 220 ce): Exam for the Nominated

Although exams were a defining feature of Keju, recruiting bureaucrats through examinations was not new in imperial China. In fact, the practice dates back to the Former Han dynasty (202 to 9 ce), the “time zero” of our historical explanation for the rise of Keju (Bielenstein, Reference Bielenstein1986). It was the first durable empire in Chinese history and employed a sizable bureaucracy (Zhao, Reference Zhao2015). The recruitment system for this bureaucracy was Chaju (察举制), which further matured in the Later Han dynasty (25–220 ce). Under this approach, imperial officials would identify individuals in possession of high morals or talent within their local jurisdictions and then nominate these individuals to sit for an examination in the capital. Upon successful completion of this test, the nominees would be recruited into the bureaucracy (Doran, Reference Doran, Denecke, Li and Tian2017).

In some aspects, exams were even more crucial for bureaucratic selection under the Chaju system during the Han than under the Keju system in the Tang. During the 7th–9th centuries, success in Keju exams only made an examinee a candidate for imperial bureaucracy, with actual appointments depending on a separate vetting process by the Ministry of Personnel (吏部), often leading to significant delays and challenges (Lai, Reference Lai2008).Footnote 8 In contrast, passing a Chaju exam more directly and swiftly led to official positions.

As emphasized earlier, the transformative aspect of Keju lies not in the use of exams per se but in the broader eligibility for exam participation. Under Chaju, exam takers were limited to a select few, as only those nominated by officials were allowed to participate. The predominant method of political selection from the 2nd-century bce to the 2nd-century ce could be described as “exam for the nominated.”

In Later Han, Chaju increasingly relied on the collective opinion of elite society in each locality to recruit new blood into the bureaucracy. Local notables in each prefecture held gatherings akin to social clubs, where they discussed and provided informal ratings for young men in their locality (Zhang, Reference Zhang2015). These ratings, though never standardized across elite societies in different prefectures, were broadly based on the men’s possession of morals and talents as perceived by the local elite.Footnote 9 As prefects in the Han took very seriously the opinion of the local elites (Brown and Xie, Reference Brown and Xie2015), the rise of an informal local “rating” system heavily influenced bureaucratic selection via the Chaju.

As the Han empire crumbled in the late 2nd century amidst civil wars, its successors faced a deeply flawed Chaju system. Functionally, the system struggled as wars and upheaval dispersed local elites, disrupting the collective assessments crucial for individual ratings. Politically, the new rulers viewed the system’s reliance on local elite opinion for appointments as a threat, fearing it could lead to state capture by localist interests.

2.2.2 The 3rd to 5th Centuries ce: Nine-Rank Rectifying System

This subsection explains the rise of another recruitment institution that was originally designed to resolve the flaws of the examination-based Chaju system. Its core mechanics, however, soon rendered the new institution equally (if not more) prone to state capture by the politically and socially privileged few.

By the early 3rd century, the fragmented warlord territories in northern China were progressively unified under the leadership of Cao Cao (曹操). Cao sought to remedy the functional and political shortcomings of the Later Han Chaju, while still incorporating the more recent development of individual rating practices. The resultant “Nine-Rank Rectifying System” (九品中正制, hereafter NRRS) was initially an effort to address both challenges. Acknowledging the absence of a stable elite society due to the civil wars and mass migrations, Cao strategically appointed members from the most prominent clans of each region to identify and recruit local talents for his government. This approach was based on the belief that these prominent clans were more resilient and retained their influence despite the turmoil of war and disasters, and, as a result, they would remain as the best “know-how” and “know-who”s in the region and could offer valuable information for bureaucratic selection (Zhang, Reference Zhang2015). Politically, the prestigious elites appointed for such roles were, by definition, Cao’s own government officials. This way, Cao made sure that those in charge of assessing and recruiting local talents shared with him the same political vision.Footnote 10

A historian writing in the late 5th-century ce considered Cao’s invention to be just an “ad hoc” (权立) solution.Footnote 11 Yet, toward the end of Cao’s reign, this assessment method had become formalized into a system where male individuals from each locality would expect an assessment of his quality from the government (Zhang, Reference Zhang2015). It was his son Cao Pi (曹丕), the founder of the “Cao-Wei” dynasty, who fully institutionalized this new method of bureaucratic selection around 220 ce (Ebrey, Reference Ebrey1978).

A simplified description of the NRRS is as follows. Each locality had a “rectifier” (中正) responsible for evaluating the “quality” of local men. Every three years, rectifiers would assign a grade from one to nine (hence the phrase “nine-rank” in the name of the system) to each educated male, with higher grades indicating superior quality. These assessments were then forwarded to a higher-level government organ for approval (e.g. Ebrey, Reference Ebrey1978; Zhang, Reference Zhang2015).

When applying for government positions, individuals were assigned entry-level roles by the Ministry of Personnel based on their most recent quality grades. These entry-level positions varied significantly in office rank, importance, and prestige. Generally, individuals with higher quality grades received more prestigious entry-level positions with higher office ranks. Starting from these positions often led to advancement to senior roles in the national bureaucracy, reaching the pinnacle of political power. Notably, these quality grades influenced not only initial bureaucratic placements but also the peak positions attainable in one’s career. Individuals with higher quality grades faced no “cap” on their career advancement, whereas those with lower grades were typically confined to lower bureaucratic levels for life.

Initially, the NRRS seemed to be a highly centralized system (Tang, Reference Tang2010; Zhang, Reference Zhang2015). A rectifier’s appointment must satisfy two eligibility conditions. One is that the appointee must originate from the locality in question. The other is that the person holding the rectifier position must be a central government official holding the post concurrently. The second requirement thus built upon Cao Cao’s practice of having government officials, rather than local elites outside the political system, make evaluations of men’s quality.Footnote 12

However, the NRRS soon fell under the control of local “aristocrats,” a term commonly referring to prestigious and wealthy landed families (such as the prominent clans mentioned earlier) from the 3rd to 6th centuries (Ebrey, Reference Ebrey1978). Typically, those selected as local rectifiers belonged to these families, as they held the cultural and moral high ground and possessed unparalleled knowledge about their locality. As one could expect, these aristocrats often assigned high grades to their own kind in the locality, who then entered civil service through prestigious and advantageous posts, conducive to further career advancement. Once these individuals secured influential positions in the bureaucracy, capable of impacting the appointment of rectifiers, they tended to favor their own kind for such roles. This practice perpetuated a cycle of intergenerational aristocratic advantage in officeholding (e.g. Miyazaki, Reference Miyazaki1977; Tang, Reference Tang2010; Zhang, Reference Zhang2015).

2.2.3 The 6th-Century ce: Decline of the NRRS and the Revival of the Examination Method

This subsection documents the decline of the NRRS and the corresponding revival of exams as a recruitment method. It emphasizes that the Chaju system was never abandoned but simply became less prominent. The rise of NRRS as part of China’s recruitment system should thus be seen as institutional layering (Mahoney, Thelen et al., Reference Mahoney, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2009). When different polities in the 6th century gradually downplayed or even repurposed the NRRS, we see that the examination method became prominent again, and the eventual emergence of Keju is arguably an outgrowth of this trend of revival.

There are two prevalent misconceptions in recent social science works on early Keju. The first is that examinations were “discontinued” from the 3rd to 6th centuries as the NRRS “arose to replace” the Chaju (Huang, Reference Huang2023, pp. 32–33). The second misconception, reflected in the likes of Chen, Fan, and Huang (Reference Chen, Fan and Huang2023), is that the NRRS remained the dominant method of bureaucratic recruitment until the exogenous introduction of Keju. However, these assertions are in fact fundamental misunderstandings.

Examinations were never discontinued as a recruitment method between the 3rd and 6th centuries. What happened was akin to institutional layering (Mahoney, Thelen et al., Reference Mahoney, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2009). Just as in the Han dynasty, those individuals nominated by local officials, once passing the exam, could still begin their careers in the bureaucracy swiftly.Footnote 13 Chaju did take a back seat from the 3rd to 5th centuries, when the majority of elites who would eventually secure ranked positions in the bureaucracy entered the civil service through the NRRS route. In contrast, those who entered via the Chaju typically secured less prestigious entry-level positions and consequently had limited career progression. Individuals opting for the Chaju route often came from relatively modest backgrounds (Zhang, Reference Zhang2015). However, starting from the late 5th century, the situation began to shift significantly in both north and south.

Northern Wei (386–535 ce): The NRRS Declined While Chaju Became Prominent Again

The Cao–Wei regime in the north was later toppled by the House of Sima, leading to the brief Western Jin dynasty (266–316 ce), which conquered the south but soon fell apart due to internal strife and pressures from the so-called barbarian groups who originated beyond the imperial frontiers. In the ensuing chaos, a Sima prince founded the Eastern Jin dynasty (317–420 ce) in today’s Nanjing, controlling the empire’s southern half. This period transitioned into the Southern Dynasties era (420–589 ce), marked by successive regimes in the south.

Meanwhile, numerous warring kingdoms in northern China, founded in the aftermath of Western Jin’s collapse, struggled to exert control over rural areas, which had become turfs of the powerful local aristocrats. In the late 4th century, nomadic warriors from the steppes established the Northern Wei dynasty (386–535 ce) under the House of Tuoba, soon conquering other northern kingdoms. A major reform in 485–486 ce allowed Northern Wei to impose direct rule over the countryside. To compensate for the aristocrats’ loss of local autonomy, the regime integrated them into the national bureaucracy, converting them from local powerholders into stakeholders of the imperial state (Chen, Wang, and Zhang, Reference Chen, Wang and Zhang2025).

Revival of Chaju was key to the recruitment of local aristocrats. From the late 5th century onward, the number of elites who entered civil service through Chaju dramatically increased. Unlike prior regimes and southern dynasties, where Chaju was left to those of lower birth, in the Northern Wei dynasty, aristocrats eagerly participated in Chaju (Yan, Reference Yan2021). Perhaps the most remarkable change was the rapid rise of Chaju as a predictor of career success. According to Yan (Reference Yan2021), among the fifty-five elites who entered the civil service through the xiucai examination (a category of Chaju for which we have the most comprehensive data), a significant 82.1% achieved ranks above Rank Five Junior.Footnote 14 Furthermore, an impressive 52.3% reached positions above Rank Three Junior, a threshold distinguishing senior government roles.Footnote 15

Yan (Reference Yan2021) also collects data for imperial and national academy students in Northern Wei. The academy system had been part of the broader Chaju institution since the Han dynasty, where students who studied in imperially sanctioned venues in the national capital could enter civil service upon passing an exam. When the Northern Wei regime revived the Chaju, it boosted the academy system as well. Among the forty-seven students for whom the data were available, a stunning 96% attained positions above Rank Five Junior, and 61.9% surpassed the Rank Three Junior threshold. Northern Wei, the regime that laid the foundation for the unified Sui and Tang empires where Keju took shape (e.g. Huang, Reference Huang1996; Yan, Reference Yan2017), witnessed the resurgence of the examination method as a prevalent and the most elitist route to the bureaucracy.

Meanwhile, the Northern Wei regime undermined the primacy of the NRRS in various ways. The first is its underutilization. Recall that, via the Reform of 485–486 ce, the regime imposed direct rule over areas that local aristocrats once enjoyed autonomy. As a part of the political deal, the Northern Wei rulers disproportionately recruited aristocrats from these areas into the upper echelon of the imperial bureaucracy. This was a crucial episode of Chinese history in which rulers substantially increased state penetration at the local level via a “compensation” package that transformed the erstwhile local powerholders into national stakeholders (Chen, Wang, and Zhang, Reference Chen, Wang and Zhang2025). These compensated aristocrats became more likely, during and after the Reform, to take a variety of important, prestigious, and powerful offices at both national and regional levels, even including ones that could constrain the rulers’ own power (Chen, Wang, and Zhang, Reference Chen, Wang and Zhang2025). One may naturally expect that the rectifier positions central to the NRRS would also be used by rulers in this master stroke of political maneuvering, but it was not the case at all.Footnote 16

Besides its diminishing role as a political tool, the prestige of the NRRS also appeared to erode during the Northern Wei period. Notably, the Tuoba emperors began appointing two groups of men from humble backgrounds to rectifier positions. The first group comprised individuals who, in the eyes of the elite society, had apparently fabricated their aristocratic identities.Footnote 17 The second group consisted of eunuchs (Yan, Reference Yan2021). This shift was particularly striking, considering that, traditionally, rectifier positions were exclusive to elites with distinguished family pedigrees. Yet now, it appears that even those considered the most despised in Chinese history could become rectifiers!

Northern Zhou (557–581 ce): The NRRS Became Largely Ceremonial

It was under Northern Zhou that the NRRS became completely sidelined. Zhou was a new regime in northwestern China that arose from the division of Northern Wei in 534 ce under the House of Yuwen. By 579 ce, the Yuwens had unified much of northern China and laid critical political groundwork for the subsequent centuries under the Sui and Tang Dynasties, with the Sui established in 581 ce via a palace coup.

Critically, the emerging consensus in historical research suggests that Northern Zhou rulers completely repurposed the NRRS to a ceremonial system, with rectifiers serving in decorative roles rather than their former bureaucratic recruitment function. The examination method via Chaju continued to rise until it blossomed into Keju in the early 7th century.Footnote 18 Contrary to the aforementioned misunderstandings, Keju did not “replace” the NRRS. There was a significant hiatus between the founding of Northern Zhou and 605–607 ce (discussed next) when Keju was allegedly introduced, during which the NRRS was already marginalized and Chaju was in full use. The emergence of Keju therefore followed a much more gradual process than a “replacement.”

Parallel to the institutional evolution in the north was a similar process in the south, where the rulers fostered “selectorate expansion” by making a qualification exam for entering the bureaucracy open to most adult males in 509 ce. This development was also built on the gradual revival of examination via Chaju even though the NRRS in the south remained vital unlike in Northern Zhou (Yan, Reference Yan2021). It should now become even clearer that selectorate expansion through examination could and did evolve from Chaju’s revival and that it did not occur as a replacement of the NRRS.

2.2.4 Keju in 605–607 and 622 ce

This subsection explores the early development of the Keju system, highlighting how it was more a continuation of gradual institutional changes rather than a revolutionary shift. Keju in the early Tang era carried the legacy of nomination and recommendation from the Chaju system, and was in fact an outgrowth of Chaju. It thus remained limited as a recruitment tool. This gradual evolution suggests that the modest changes in 622 ce were unlikely to have been seen as transformative in the eyes of the beholders.

The institution later known as the Keju formally began in the early 7th century. However, pinpointing the exact year of its inception has been a subject of intense debate among historians. This debate primarily revolves around multiple proposed dates. Dominant among these are the perspectives of the “pro-Sui camp” and the “pro-Tang camp.” The pro-Tang camp’s rationale is straightforward: They argue that the Keju, known for offering individuals from modest backgrounds a chance to compete, could only have started when examinees were allowed to participate through self-nomination. In their view, Keju began when it was no longer the Chaju, examination for those nominated by government officials. For them, Keju began when it “expanded” in 622 ce, under the Tang dynasty, for the exact reason discussed in the beginning of this section.Footnote 19 On the other hand, the pro-Sui camp suggests two possibilities: 587 and 605–607 ce, with the latter receiving more emphasis.Footnote 20 In 605–607 ce, the examination category known as Jinshi (进士科) was introduced.Footnote 21 By the late imperial China (14th to 19th centuries), Jinshi had become synonymous with the highest and final degree of the Keju examination.

The very existence of this debate itself is important for social scientists interested in institutions. It suggests that significant institutions like the Keju often do not emerge as sudden, transformative shocks with immediate impact. If the Keju had been such a pivotal institution effecting immediate change upon its inception, then its founding year, and specifically what kind of institutional changes should really constitute as the inception of Keju, would likely not be as disputed. By examining these years chronologically, we demonstrate that neither marked a significant change at their respective times. Rather, the developments in these early years of the 7th century were simply a continuation of the long history of gradual institutional change that began in the Han dynasty and continued until the end of the 6th century, as documented earlier.

Between 605 and 607 ce, Emperor Yang of the Sui dynasty (隋炀帝) promulgated a series of edicts that some modern historians cite as marking the inception of Keju.Footnote 22 A detailed examination of these edicts reveals that this so-called inception was more a continuation of an existing trend rather than a new beginning.Footnote 23 In 605 ce, Emperor Yang decreed that officials should “identify and recruit talent based on their abilities” within their respective jurisdictions. This decree also included a provision for talented individuals who chose not to join the bureaucracy, stipulating that such individuals should still receive a state salary “proportional to their abilities and their family pedigree.”Footnote 24 In 607 ce, the emperor issued another edict, part of which simply said: “Those who hold government positions at Rank Five or above should nominate people to participate in one of the ten categories of the imperial examination.”Footnote 25 Taken together, these two edicts do not reveal any significant departure from the Chaju tradition since the Han dynasty. The eligibility for the imperial examination continued to be limited to individuals nominated by government officials. Thus, the Imperial Examination System of the Sui dynasty appears as a natural progression of the Chaju system. This evolution should be viewed in the context of the revival of Chaju and the decline of the NRRS over Northern Wei and Northern Zhou, the predecessors of Sui regime. In short, the institutions “created” in 605–607 ce were, just as Chaju was, exam for the nominated. The 607 edict is of particular importance because there seems to be a technical connection between this edict and the one in 622 ce marking the selectorate expansion, which we address next.

In 622 ce, as previously mentioned, Emperor Gaozu of Tang issued an edict expanding the Keju system. The provisions regarding imperial examinations in this edict closely resembled those from the 607 ce edict, with both requiring officials of “Rank Five” and above to nominate talented individuals.Footnote 26 The edict of 622 ce, however, included a minor addition at the end: “those talents not nominated by these officials should self-nominate to participate (in the exams).”Footnote 27

There are several reasons to doubt that the developments in 622 ce would have been perceived as revolutionary at the time. First, these developments were a direct continuation of the preceding institutional changes, particularly the revival of recruitment through examinations and the decline of NRRS. Second, the 622 edict essentially built upon its 607 predecessor, with the addition of self-nomination – a discernible yet minor refinement – appearing only at the end of the provision regarding the imperial examination.

One way to appreciate the minimal nature of this step is by examining the composition of top officials in the Tang dynasty. During the reigns of the first two emperors, when this selectorate expansion occurred, fewer than 22% of chief ministers entered the bureaucracy initially through Keju. Among these six chief ministers, five had prestigious family background, with only one being a complete outsider to the system.Footnote 28 Data from Tang dynasty epitaphs, representing a broader elite spectrum, paints a similar picture (Wen, Wang, and Hout, Reference Fangqi, Wang and Hout2024). Among the elites who passed away before 649 (the end of the second Tang emperor’s reign), only 3.8% held a Keju credential. Throughout the 7th century, merely 8% of new recruits into the bureaucracy had Keju credentials. In short, statistics from both the highest echelons of political power and the broader elite society reveal that Keju’s role in early Tang politics was not only quite limited as a tool for general recruitment, but it also predominantly functioned as a pathway for the powerful few to attain office, even following the expansion in 622.

These figures should not be surprising to those familiar with early Tang history, where the nascent examination system continued the legacy of nomination, and the political selection process still mirrored the entrenched interests of the incumbent elite. A notable instance is the case of Zhang Chujin (张楚金), who was selected by his local government to take the imperial exam in the capital, over his brother. Zhang offered to relinquish this opportunity, arguing to the local authorities that his brother was more talented. This act caught the attention of Xu Shiji (徐世绩), a regional superintendent and high-ranking government official, who intervened to have both brothers nominated for the exam. Xu, a distinguished founding elite of the Tang dynasty and a close ally of the first two emperors, had earned the privilege of adopting the imperial surname “Li.” The Zhang brothers were related to another high-ranking founding elite, once a colleague of Xu in the central government.

While Tang historical records depict this episode as demonstrating Zhang’s talent and humility, and Xu’s knack for recognizing true talent, it also unwittingly reveals how patronage and privilege could manipulate the system. Notably, the record ends with the phrase “he nominated both to pass the final exam” (emphasis added).Footnote 29 This implies that, from the perspective of Tang contemporaries, Xu’s intervention was seen as ensuring their success in the final stage of the exam, not just their chance to participate. More significantly, this episode highlights that despite the 622 Keju expansion allowing for self-nomination, the long-standing tradition of Chaju, particularly nominations by government officials, continued to play a pivotal role in the examination system.

To sum up, by documenting the abundant primary and secondary evidence, this subsection demonstrates that the beginning of Keju was very much a continuation of gradual institutional change over the long durée. The legacy of prior institutions, especially the Chaju system, still loomed large in the early years of Keju. Furthermore, in the early Tang era, Keju’s role was quite constrained both in and of itself as a recruitment institution and as a political tool to expand the selectorate. Its limited use appeared to be practically (though not legally) restricted to those with patronage and power. Consequently, it seems highly improbable that the modest adjustment in 622 ce (and even less so in 605 or 607 ce) was regarded as a groundbreaking change by the “aristocrats,” however they are defined.Footnote 30 Instead, the bulk of evidence points toward a “business as usual” sentiment prevailing among the elite of that era.

2.2.5 Keju as Ad Hoc Solution

While it’s challenging to ascertain the emperor’s exact intentions behind the 622 Keju expansion, attributing it solely to an effort to undermine the aristocracy overlooks a more plausible functionalist explanation that is well aligned with critical political developments preceding the Tang. A notable trend was the administrative and political centralization initiated during the Northern Zhou period and pursued vigorously by the Sui. This legacy of centralization was inherited by the Tang and would persist throughout the subsequent history of imperial China for over a millennium. It’s beyond the scope of this work to elaborate on these policies in detail, but the essence of the most pivotal one was that, previously, prefects had the autonomy to appoint their own staff, typically drawn from local elites, for their prefecture governments. Now, the central government appointed virtually all officials within the prefecture government. This shift was viewed as a transformational strategy that significantly redirected power from local governments and local elites toward the central government (e.g. Ebrey, Reference Ebrey1978; Jin, Reference Jin2015). However, this change undoubtedly placed a burden on the central government to devise mechanisms for official selection, as officials even at the very local level now required direct appointment from the center.Footnote 31 Keju, though still in its early stages, emerged as one of the centralized responses to this need for centralized recruitment.Footnote 32

Another significant trend is the migration of local aristocrats to the imperial capitals, a phenomenon referred to as the “centralization of the aristocracy.” This movement began in the late 5th century (Chen, Wang, and Zhang, Reference Chen, Wang and Zhang2025), intensified during the 6th century (Ebrey, Reference Ebrey1978), and by the 8th century, most Chinese aristocrats had severed ties with their original hometowns (Tackett, Reference Tackett2020). Such developments challenge the notion that the emergence of Keju, particularly as a substitute for the NRRS, aimed to undermine the “aristocracy.” To the extent that the NRRS and Chaju benefited the aristocrats, it’s because both systems were locally organized in a way that particularly put aristocrats into the formal (as in NRRS) or informal (as in Chaju) position to favorably grade (as in NRRS) or nominate (as in Chaju) their own kind from the same locality for political office. Their relevance for the reproduction of political power by the aristocrats (allegedly for generations) now diminished as aristocrats became less localized. Consequently, the discontinuation of the NRRS (and similarly, Chaju) arguably did not significantly weaken aristocratic influence as much as some grand narratives suggest. In fact, the centralized nature of Keju, in this very sense, could be seen as beneficial to the aristocrats, now increasingly centralized in residence. Candidates from the capital enjoyed numerous advantages in the Keju (Fu, Reference Xuancong2020).Footnote 33 The decline of the NRRS, once beneficial to local powerholders, occurred as aristocrats shifted from local powerholders to centralized elites. This transition, coupled with the rise of Keju that would favor centralized elites, suggests that Keju’s introduction was unlikely to undermine the aristocracy. This is not to say that Keju would not facilitate social mobility, which it did in the Tang (Section 3). Our argument is simply that the rationale for it was unlikely anti-aristocratic in as early as 605 or 622 ce.

The particular “breakthrough” in 622 likely reveals a functionalist logic as well. The Tang dynasty was founded in 618 as a series of peasant and elite rebellions destroyed the Sui empire. It was initially a regime based in Chang’an (长安) and its surrounding regions, but later reconquered the rest of China, then dominated by numerous rebellion leaders fighting with one another. There is abundant evidence that elites (outside the Guanlong “northwestern” regions) in the early years of the dynasty were uninterested in politics, perceived as unstable, chaotic, and dangerous.Footnote 34 The aforementioned centralization efforts of the Tang’s predecessor regimes had already posed recruitment challenges for the Ministry of Personnel. Thus, the Tang faced particularly significant difficulties in political selection, especially given the urgent need to staff the new government amidst widespread chaos and uncertainty. Coupled with the unprecedented need for local talents was the lack of information allowing the rulers to identify them. The centralization of aristocrats and a century of elite migration amidst waves of wars and upheavals in the 6th century had only worsened the information gap. At one point, the founding emperor was so desperate that he even reinstated the NRRS in 624 ce so that “an aristocrat in each locality would be a rectifier to evaluate people’s quality.”Footnote 35 Yet, precisely because the aristocrats were no longer in their ancestral homes (“choronyms”), this initiative faltered and was quickly discontinued (Jin, Reference Jin2015, p.38). It seemed only natural that amid the desperate need for talents and the severe lack of information to identify them, the edict in 622 would allow individuals to self-nominate. The method of examination, from an informational perspective, was now also more important than ever.

To sum up, via detailed analysis of primary materials and secondary literature, we have highlighted the rise of Keju as a continuation of the gradual institutional change in early and medieval China over the long durée. The eventual breakthrough, the political effect of which could only manifest itself ex post (Sections 3 and 4), was most likely an ad hoc technical solution to new challenges in bureaucratic recruitment. The mechanism of institutional change in our account is similar to “layering” in historical institutionalism (e.g. Mahoney, Thelen et al., Reference Mahoney, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2009). The initial policies that scholars would later attribute the Keju to could be best understood as new layers added to the Chaju system whose evolution had a reversal of fortune vis-à-vis the NRRS.

Our account also contributes to the theory of bureaucracy as a solution to address informational asymmetries between the ruler and the ruled (Stasavage, Reference Stasavage2020). The bureaucratic solution would not be feasible if the initial level of information gap is prohibitively high: To recruit bureaucrats who would sustain the bureaucracy, one needs some information about local talents to begin with. In contexts where such knowledge was severely lacking, Keju arose as a solution.

Keju in 622 ce as Magna Carta in Reverse?

The Keju breakthrough in 622 ce, in our analysis, can be viewed as a Magna Carta moment in Chinese history, albeit in reverse. Like the royal Charter of 1215 ce, the edict issued by Emperor Gaozu had a profound impact on the balance of power between the ruler and the upper elites; however, in the Chinese case, the balance tilted in favor of the ruler rather than the nobles, as in the English context. The more significant similarity between these two moments is that the transformative nature of each could not have been envisaged by contemporaries. In England, it was subsequent political developments later in the century – such as “Henry III’s minority, his foreign ambitions, his lack of funds, and the general unpopularity of his government” – that eventually elevated the Charter’s importance in politics and the future institutionalization of parliament (Maddicott, Reference Maddicott2015, p.24). Similarly, this section discusses how regime changes, rulers’ centralization efforts, drastic civil wars, and elite migrations induced the emergence of Keju as a contingent solution. The next section details additional forces at play in the following three centuries that retrospectively make 622 ce appear eventful in a reverse Whiggish manner.

2.2.6 An Existing Study

Before moving on, we address an existing economics study that attempts to use 605 ce as the “treatment” year for the emergence of Keju (Chen, Fan, and Huang, Reference Chen, Fan and Huang2023). The paper analyzes a limited set of biographies from Chinese dynastic histories spanning from 265 to 1644 ce. Its core finding is that after 605 ce, bureaucrats who last served as local administrators were more likely to be purged than those who last served in central ministries. The authors use this result to argue that Keju undermined the aristocracy. Our critique underscores a key point: Keju did not emerge as a sudden shock but rather as a gradual process, evolving alongside various other developments over an extended period.

We outline four major flaws in the study, with a detailed analysis provided in the Online Appendix. First, the authors misreported the timing of the treatment. They cite Miyazaki (Reference Miyazaki1981) to support 605 ce, despite this source clearly stating that Keju began in 587 ce, with no mention of 605 ce in its timeline of institutional changes. Notably, 587 ce falls just before the treatment decade in the authors’ event study. Second, as discussed in Section 2.2.4, any form of Keju before 622 ce still limited candidacy to those nominated by incumbent elites, likely reinforcing rather than undermining aristocratic dominance. Third, the authors’ operationalization of aristocracy is highly unconventional, equating local (central) administrators with “commoners” (“aristocrats”), a view not supported by the historical sources they cite.Footnote 36 Lastly, as detailed in the Online Appendix, numerous events and political changes in the decade following 605 ce likely altered the fortunes of both nobility and commoners, further confounding the study’s results, but the authors did not disclose these well-known historical facts.

Our critique highlights the gradual nature of Keju’s emergence, making it impossible to pinpoint a singular “treatment” effect. Historians have identified at least ten different eras for the emergence of Keju (Liu, Reference Liu2000). These ambiguities and controversies arise because Keju evolved gradually as an outgrowth of earlier institutions, rather than emerging as a significant, singular event.

3 Early Development

This section explains how Keju gradually became the dominant pathway to power despite its minimal and ad hoc beginnings. First, it uses qualitative evidence to show how the aristocrats failed to recognize that Keju would eventually promote social mobility, leading to their lack of collective resistance. Specifically, Keju’s rise was so gradual that the “signal” of this development was hard to discern from the various noises of politics. Next, it quantitatively confirms the gradual increase in the importance of Keju, establishing that it had indeed become significant over time. Finally, it explores the institution’s positive feedback (Mahoney, Thelen et al., Reference Mahoney, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2009), in which both rulers and the broader elite came to see Keju as beneficial. The rulers gradually realized that Keju had the potential to equalize political opportunities and expand the selectorate, while specific political developments in the latter half of the Tang made Keju more central to career success for the elites.

3.1 Signal versus Noise: What Happened under Empress Wu?

Thus far, we have demonstrated that Keju emerged from a gradual institutional evolution spanning four hundred years. This period witnessed the initial decline and subsequent revival of examinations in bureaucratic recruitment. To the contemporaneous elites, its “inception” – if there was one to speak of – would likely have been perceived not as a revolutionary break, but as a continuation of an ongoing process. However, there is no denying that by the end of the Tang, Keju had become a game changer. By the mid-7th century, less than 22% of the Tang chief ministers entered the bureaucracy through Keju, but this proportion increased to a stunning 85% for chief ministers in the 9th century. Furthermore, only 3.8% of the male elites had examination credentials by the mid-7th century, but the number increased to 17.6% for male elites in the 9th century.Footnote 37

Given its modest beginnings, what explains Keju’s rise over the next three hundred years? A popular theory credits Empress Wu (武则天) in the late 7th century. As the only female monarch in a Confucian society, she faced strong opposition from the aristocracy and is thought to have promoted Keju to weaken their influence by introducing new talent into the bureaucracy. This idea, proposed by historian Chen Yinke in the 1940s, has faced significant criticism over the years but has recently been revisited by social scientists like Huang (Reference Huang2023), who argue that Keju strengthened autocratic rule.Footnote 38

While several changes under Empress Wu could have elevated Keju – such as allowing more people to pass exams, holding exams more frequently, and shifting the exam focus toward literature – there was no significant aristocratic dissent recorded, making this narrative difficult to substantiate. This lack of resistance returns us to our initial puzzle: Why did the aristocracy not resist more? In what follows, we explore this question through a thought experiment.

Unlike the minimal changes in 622 ce, the shifts in Keju during Empress Wu’s reign may have been significant enough to be noticed. However, political selection is a noisy process, and for the powerholders to react, the signal of what these changes meant for political power needed to be clear. In Tang politics, a clear signal would have been the rising importance of Keju in appointing chief ministers, but it’s possible that the powerholders struggled to distinguish signal from noise.

Among the 105 individuals who served as chief minister during Empress Wu’s era (649–705 ce), 32.11% began their bureaucratic careers through Keju.Footnote 39 This percentage represents a 50% increase from the era of the dynasty’s first two emperors (618–649 ce), a rise that could have been noticeable at the time. The key question, however, is whether these Keju-credentialed chief ministers became chief ministers because of Keju. This question is not one of “causal identification” in the pedantic sense. It is simply whether the incumbent powerholders at the time intuitively perceived that success in Keju, a competition with a relatively level playing field even for their own children, was becoming increasingly important for officeholding.Footnote 40 The answer is: unlikely.

When someone ascends to a top bureaucratic position after decades of service, many of his traits would have been observed, with passing a written exam decades earlier being just one of them. In this thought experiment, we suggest that discerning the rise of Keju as a key factor in appointing a chief minister, amidst other “confounding” factors, would be challenging for a powerholder. Take the example of Di Renjie (狄仁杰), whose administrative competence and moral integrity were widely praised by contemporaries. During his term in the Ministry of Justice, he reportedly resolved 17,000 backlogged cases in one year without any complaints of injustice. He also saved an official from wrongful execution, even daring to openly confront the Emperor Gaozong for this cause. The Emperor later rewarded him for his courage and integrity.Footnote 41 It seems unlikely that other elites would attribute his eventual promotion to chief minister to his earlier Keju success rather than to his widely recognized qualities. Another example is Wei Siqian (韦思谦). His exemplary county governance early in his career earned significant acclaim. Then as an imperial censor, he was praised for impartiality. He even launched anti-corruption charges against a chief minister, who revenged by demoting him. Several years later, the same chief minister was killed for opposing Wu’s promotion to Empress. Wei’s career subsequently advanced, attaining important positions. Wei then got promoted again, attaining important positions throughout his career. When Wei became chief minister at the age of seventy-four, it would have been difficult for others to see this as a result of passing the Keju four decades prior, rather than his administrative capabilities and a political gamble that eventually paid off.

To systematically document these “noises,” we compile original data on recorded qualities. For each of the thirty-five chief ministers with a Keju background, we examined their biographies in the Old Book of Tang and New Book of Tang, assessing whether they were also noted for merits or achievements in areas relevant to high office promotion: morality, literature, military, civil administration, knowledge of rituals, and notable political deeds.Footnote 42 Remarkably, 91.4% had merits recorded in at least one of these dimensions. Excluding “literature,” a dimension often seen as closely tied to Keju success, this percentage still stands at a significant 77.1%. This exercise confirms our idea that the aristocratic powerholders were unlikely to detect the signal of Keju’s rising primacy from the “noises” as far as political power was concerned.

The rise of Keju continued throughout the era of Empress Wu. While the changes it had brought to political power were noisy enough initially, they had become clearer over time. After dividing Empress Wu’s era into earlier (649–689 ce) and later (690–705 ce) periods, we see that the 32.3% of the chief ministers were Keju-credentialed in the earlier period, but the number grew to 43.1% in the later period.Footnote 43 Following a brief interlude after Wu stepped down in 705 ce, Tang China entered its stablest and most prosperous era under Emperor Xuanzong, which lasted until 755 ce. Between the end of Wu and the end of Xuanzong, this percentage rose to 61.9%. Given that becoming a chief minister was the ultimate aspiration for Tang elites, the majority having ascended through the examination system was a clear indicator of Keju’s significance. By the mid-8th century, Keju had arguably become the primary route to the highest echelon of political power. Should a time machine have existed, a Tang elite from the mid-7th century traveling forward a century would likely find the politics of bureaucratic recruitment dramatically transformed upon looking back.Footnote 44

3.1.1 What the Data Says

Now we illustrate the gradual yet significant rise of Keju throughout the Tang dynasty with more systematic data. Our analysis is based on career data from 3,640 epitaphs of adult males from the Tang period, drawn from Wen, Wang, and Hout (Reference Fangqi, Wang and Hout2024).Footnote 45 Unlike biographies from dynastic histories that predominantly feature high-ranking elites and political “winners,” epitaphic data is widely acknowledged by historians of medieval China as providing a more representative sample of the broader Tang elite society (e.g. Jiang, Reference Jiang2006, Reference Jiang2012; Tackett, Reference Tackett2014, Reference Tackett2020).Footnote 46 We use the following specification:

The level of analysis is individual, the deceased person for whom the epitaph was written. The outcome is the rank of the last office obtained in his career, which takes zero if he had not been in the bureaucracy. X denotes k number of independent variables, including whether he had passed the Keju, the rank of the highest office taken by his father, the rank of the highest office taken by his grandfather, whether he belonged to a prominent aristocratic branch, and whether he belonged to the elite marriage network based in the two capitals of the Tang dynasty (Tackett, Reference Tackett2020).Footnote 47 This specification therefore follows Wen, Wang, and Hout (Reference Fangqi, Wang and Hout2024) to decompose “medieval aristocracy” into two dimensions. One is the power of the individual’s immediate ancestors, measured by the office ranks of the father and grandfather. Another is the pedigree of the bloodline itself, proxied with membership in a prominent branch of a choronym-surname.Footnote 48

The person’s decade of birth is denoted by t, which we refer to as “time.” We evaluate the effects of these variables, Keju in particular, on the individual’s political achievement over time by including the interaction between them and the square and cubic terms of birth year with T and

![]() . The province-time fixed effects are denoted by

. The province-time fixed effects are denoted by

![]() , where p denotes the modern province in which the epitaph was excavated, and

, where p denotes the modern province in which the epitaph was excavated, and

![]() is the interaction between time dummies and ancestral regime dummies. As China was divided into three regimes in the northwest, northeast, and south before unification under the Sui-Tang empire, elites serving in the Sui and Tang Dynasties might belong to different factions based on the geopolitical identities of the regime their family descended from.Footnote 49

is the interaction between time dummies and ancestral regime dummies. As China was divided into three regimes in the northwest, northeast, and south before unification under the Sui-Tang empire, elites serving in the Sui and Tang Dynasties might belong to different factions based on the geopolitical identities of the regime their family descended from.Footnote 49

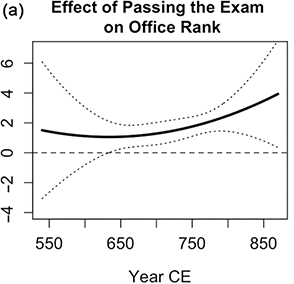

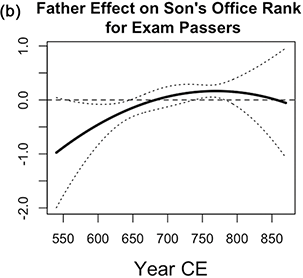

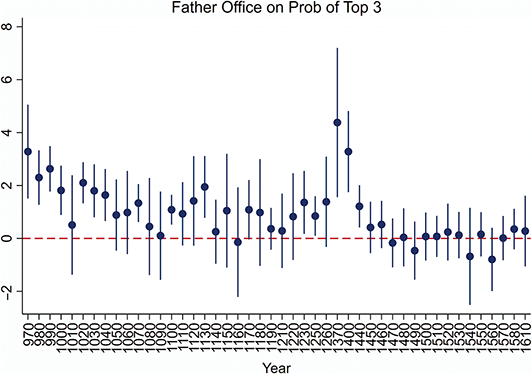

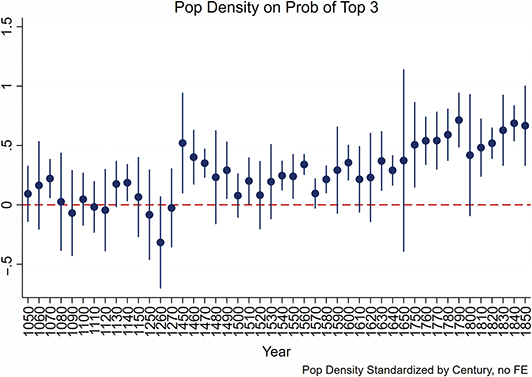

Figure 2(a) shows that the significance of Keju success as a predictor of an elite’s political achievement increased over the course of the dynasty. Initially, its predictive power for office rank was indistinguishable from zero. However, the lower bound of the confidence intervals went above zero for cohorts whose political coming-of-age coincided with the initial ascendancy of Empress Wu. Since then, the significance of Keju had continued to grow. For cohorts active in the late Tang, passing the Keju could translate into a career advantage of two full ranks within the bureaucracy’s nine-rank system.Footnote 50 The continuously increasing trend of Keju’s importance, gradual but substantial, is consistent with our qualitative analysis at the beginning of this section.

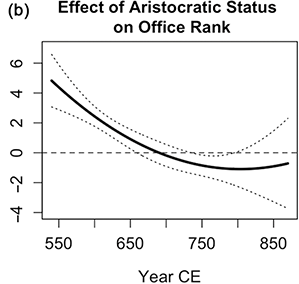

Panel (a) shows the effect over time of passing the Keju on one’s office rank.

Panel (b) shows the effect over time of being a member of a prominent aristocratic branch on one’s office rank. Both are with 95% confidence intervals.

We now explore the association between aristocratic status and political success, where two key observations emerge from the right panel. First, the significance of belonging to a prominent aristocratic branch for securing office positions declined throughout the Tang dynasty. By the generation born in the mid-7th century, aristocratic status ceased to be a reliable predictor of career success. Because whether an individual could be credibly traced to a prominent aristocratic branch is technically measured “before” his father and grandfather office ranks, his status in the marriage networks, and his success in the Keju, X in the specification excludes such control variables.Footnote 51 Second, this downward trend in the value of aristocratic lineage predated the rise in importance of Keju, as evidenced in the left panel. This contrast further casts doubt on the grand narrative critiqued throughout this Element that early Tang Keju aimed to undermine the “aristocracy.”

The empirical results here, alongside Wen, Wang, and Hout (Reference Fangqi, Wang and Hout2024), challenge the recent “persistent school” in Tang studies, which downplays the significance of Keju and overemphasizes the enduring influence of aristocratic advantage in officeholding (e.g. Tackett, Reference Tackett2014, Reference Tackett2020).Footnote 52

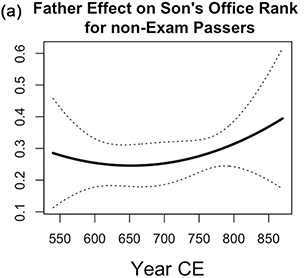

This does not imply that family background was inconsequential. In fact, findings in Wen, Wang, and Hout (Reference Fangqi, Wang and Hout2024) indicate that the office ranks of both fathers and grandfathers had a positive impact on the office rank of sons, with these trends remaining stable over time (neither increasing nor decreasing). Given that the significance of immediate ancestors in an individual’s success is a universal phenomenon across various cultures and eras, its consistent importance in the Tang dynasty is hardly surprising.Footnote 53 By comparing the steady influence of immediate ancestors’ ranks with the declining significance of broader ancestral prestige, it can be argued that in the era of examinations, the bureaucracy in medieval China became less “medieval” and aristocratic.

What about the effect of family background on examination success? A prevailing notion in the literature on Keju during the Tang dynasty states that the overwhelming majority of Keju passers (those who succeeded in the exam) were themselves “aristocrats” (Sun, Reference Sun1980; Mao, Reference Mao1988; Kung, Reference Kung2022). This statistical claim is problematic on multiple levels. First, a complete government roster of Keju passers (those who succeeded in the exam) from the Tang dynasty was never preserved. Any effort by post-Tang historians to compile a complete “list” of Tang Keju passers has had to either rely on reading biographies from dynastic histories, a sample that is severely biased for various reasons (e.g. Jiang, Reference Jiang2006, Reference Jiang2012; Tackett, Reference Tackett2014, Reference Tackett2020), or rely on secondary “catalogues” (e.g. Dengke Jikao 《登科记考》), which in turn relied heavily on dynastic histories.Footnote 54 When historians compute the proportion of aristocrats in any such “list,” those outside the list and those inside the list but without detailed family information are essentially omitted from the denominator, leading to upward bias in favor of aristocratic dominance as prestigious family backgrounds were more likely to be recorded in history.Footnote 55

Second, works claiming that the overmajority of Keju passers were aristocrats employ definitions of “aristocrats” that not only are excessively expansive but also fundamentally deviate from the Tang reality. Their definitions rely solely (as in Kung, Reference Kung2022) or significantly (as in Sun, Reference Sun1980 and Mao, Reference Mao1988) on “choronym-surname” combinations (“choronym” meaning an elite’s ancestral hometown).Footnote 56 There is overwhelming consensus among historians that the fabrication or “concoction” (建构郡望) of choronyms was widespread in the Tang (e.g. Qiu, Reference Qiu2016; Fan, Reference Fan2014).Footnote 57 Anyone with surname Li, an extremely common surname in Chinese history and today, could claim to come originally from the choronym Longxi or Zhaojun and enter the data in these works as a member of the aristocratic clan “Li of Longxi” (陇西李氏) or “Li of Zhaojun” (赵郡李氏).Footnote 58 In addition to these two major problems, the methodology of computing

![]() from any “list” of Keju passers is itself inherently flawed as it selects on the dependent variable.

from any “list” of Keju passers is itself inherently flawed as it selects on the dependent variable.

The more adequate approach would be to obtain a sample of Tang elites, which would inevitably contain individuals with Keju credential and individuals without it, and employ a precise definition of aristocrats that reduces the fabrication bias inherent in choronym-based measures that has been well-documented in the historical literature. The epitaph sample and the methodology of measuring the pedigree dimension of medieval Chinese aristocracy in Wen, Wang, and Hout (Reference Fangqi, Wang and Hout2024) underpins this approach. Our simple calculation suggests that only 38% of the Keju passers in the epitaph sample could be credibly traced to prominent aristocratic branches, much lower than prior estimates.Footnote 59

More importantly, econometric analyses by Wen, Wang, and Hout (Reference Fangqi, Wang and Hout2024) suggest that none of the family background measures consistently predicts exam success, whether they are father or grandfather office ranks, membership in elite marriage networks based in the Tang capitals (a measure of aristocracy preferred by Tackett (Reference Tackett2014)), or membership in a prominent aristocratic branch.Footnote 60 These nonresults should not be misconstrued to suggest that the Keju contest was entirely equitable across all societal classes or groups. The epitaph sample primarily reflects the elite segment of Tang society – individuals who were highly educated and could afford epitaphs. However, these nonresults in Wen, Wang, and Hout (Reference Fangqi, Wang and Hout2024), along with the concurrent trends of increasing Keju importance and diminishing aristocratic influence reported in Figure 2, support our argument in Section 1 that Keju broadened the “selectorate” by leveling the playing field within the elite class. The remainder of this section will explore how Keju evolved into a self-enforcing institution perceived as beneficial by both the emperor and (to some extent) elites, where we will further illustrate the equalizing nature of the Tang Keju through additional qualitative and quantitative evidence.

3.2 Self-reinforcing Institution

We now move to the next question: Why did Keju become an institution that sustains itself. Our answer is that both the ruler and the elites increasingly found it beneficial. For the ruler, although we initially minimized the notion that Keju was intentionally implemented to weaken the aristocracy or existing political powerholders, from a certain point onward, it became increasingly clear to the Tang emperors themselves that Keju indeed could serve such a political purpose. For the elites, they adapted to the new paradigm and began to view the Keju-credential as a key step in their political promotion. Our discussion starts with the perspective of the ruler.

3.2.1 The Equalizing Potential of Keju

Even in the subsection discussing Empress Wu, whom some historians and social scientists view as a crucial advocate of Keju with the aim of undermining the upper elites, we remain agnostic regarding her actual intentions, emphasizing instead the incremental and “noisy” evolution of Keju and consequently the absence of elite resistance. Nonetheless, it prompts the question of when Tang emperors eventually began to recognize Keju’s potential to serve the purpose often attributed to it: enhancing the ruler’s power. While it is impossible to look inside a ruler’s mind, we consider the increasing attention to a specific political issue as indirect evidence of Tang emperors acknowledging Keju as a tool to broaden the “selectorate.” This issue pertains to the participation of zidi (子弟) in the exam.