Phonology, homophony, and eyes-closed rest in Mandarin novel word learning: An eye-tracking study in adult native and non-native speakers

When it comes to learning Mandarin, lexical tones are an inevitable topic. There are four main tones in Mandarin: tone 1 is high-level, tone 2 is high-rising, tone 3 is low-dipping, and tone 4 is high-falling (Chao, Reference Chao1930; Zhang & Lai, Reference Zhang and Lai2010; Zhu & Wang, Reference Zhu, Wang, Wang and Sun2015). This tonal system is notorious for being difficult to learn for non-native speakers. While some research shows that tonal contrasts are more difficult for learners from a non-tonal first language (L1) background than for those from a tonal L1 background (Cooper & Wang, Reference Cooper and Wang2012; Poltrock et al., Reference Poltrock, Chen, Kwok, Cheung and Nazzi2018; Schaefer & Darcy, Reference Schaefer and Darcy2020), speakers of tonal L1s do not necessarily outperform speakers of non-tonal L1s in non-native tone perception and word learning (Laméris & Post, Reference Laméris and Post2022; So & Best, Reference So and Best2010). However, another characteristic of Mandarin—the abundance of homophones—is often neglected in adult lexical learning. In the current study, we investigated the combination of these two Mandarin features, phonology and homophony, in a novel word learning experiment that tested both native and non-native speakers. In addition, we were interested in whether participants’ performance would be affected by a short break with either an eyes-closed rest or a distractor task (i.e., playing a computer game). The available evidence suggests that short periods of rest help memory consolidation and facilitate learning, in a similar manner to sleep (Brokaw et al., Reference Brokaw, Tishler, Manceor, Hamilton, Gaulden, Parr and Wamsley2016; Dewar et al., Reference Dewar, Alber, Butler, Cowan and Della Sala2012; Wamsley, Reference Wamsley2019).

Mandarin tonal contrasts and novel word learning

A number of studies have demonstrated the challenge of learning Mandarin tonal contrasts in adult non-native speakers, who come from a variety of linguistic backgrounds such as English (Hao, Reference Hao2018, Reference Hao2023; Shen & Froud, Reference Shen and Froud2016), Dutch (Sadakata & McQueen, Reference Sadakata and McQueen2014; Zou et al., Reference Zou, Chen and Caspers2017), Thai (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Munro and Wang2014), and Japanese (Tsukada et al., Reference Tsukada, Kondo and Sunaoka2016). These findings (alongside others, e.g., Kann et al., Reference Kann, Barkley, Bao and Wayland2008; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Chen and Yang2021) suggest that despite difficulties, adult speakers are capable of learning non-native tones to a certain degree. This is especially the case in tonal L1 speakers (Chan & Leung, Reference Chan and Leung2020). For example, Wayland and Li (Reference Wayland and Li2008) reported that Mandarin-L1 speakers outperformed English-L1 speakers when discriminating the low- vs. mid-tone contrast in Thai. Similarly, using a Cantonese tone discrimination task, Qin and Mok (Reference Qin and Mok2011) found that Mandarin-L1 speakers performed significantly better than English-L1 and French-L1 speakers. Nonetheless, both L1 tonal status and L1 tone type affect individual performance in tonal learning (Laméris & Post, Reference Laméris and Post2022), and tonal L1 speakers may perform worse than their non-tonal L1 counterparts in certain psycholinguistic tasks. For instance, Hao (Reference Hao2012) observed significantly lower accuracy among Cantonese-L1 speakers when perceiving Mandarin tone 4 and producing Mandarin tone 1 than among English-L1 speakers. Therefore, the specific tonal contrasts involved appear to be crucial when comparing performance between tonal and non-tonal L1 learners. However, the existing literature has primarily focused on speech perception and production (Ning et al., Reference Ning, Shih and Loucks2014; Shen & Froud, Reference Shen and Froud2016; Tsukada et al., Reference Tsukada, Xu and Rattanasone2015; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Spence, Jongman and Sereno1999), with much less research conducted on novel word learning.

Novel words can be defined as pseudowords that are phonologically legal but not associated with any meaning (Ziegler et al., Reference Ziegler, Besson, Jacobs, Nazir and Carr1997), i.e., they are possible, but not existing words. A majority of lexical learning studies using novel word learning designs pertain to infants and young children (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Tardif, Chen, Pulverman, Zhu and Meng2011; Chen & Liu, Reference Chen and Liu2014), especially comparing monolingual and bilingual infants (Burnham et al., Reference Burnham, Singh, Mattock, Woo and Kalashnikova2018; Byers-Heinlein & Werker, Reference Byers-Heinlein and Werker2013; Singh et al., Reference Singh, Poh and Fu2016; Wewalaarachchi & Singh, Reference Wewalaarachchi and Singh2020). Among the relatively few studies with adults, most have focused on tonal learning. For example, Wong and Perrachione (Reference Wong and Perrachione2007) found that non-native tones can be learned by English-L1 speakers when identifying English pseudowords superimposed with pitch patterns resembling Mandarin tones. Also using a lexical identification task, Laméris and Post (Reference Laméris and Post2022) suggested that “tonal rather than segmental distinctions were the hardest feature to memorize in the pseudolanguage words” (p. 857) for both English-L1 and Mandarin-L1 speakers, given that most errors were tone-only errors. Similar findings were observed in Chang and Bowles (Reference Chang and Bowles2015), who reported more tonal errors than segmental errors by English-L1 speakers while learning disyllabic Mandarin pseudowords. Note that most of these studies, like the present one, used stimuli made up of segments that occur in both Mandarin and English. Therefore, while the pseudowords were new to the learners, the segmental contrasts distinguishing them were already familiar from English, as pointed out to us by an anonymous reviewer (but see Wright & Baese-Berk, Reference Wright and Baese-Berk2022, on learning Thai tone contrasts and phonotactics).

In addition to tonal learning, several studies have investigated the role of tonal and segmental information in Mandarin spoken word recognition (Li et al., Reference Li, Wang, Davis and Guan2018; Malins & Joanisse, Reference Malins and Joanisse2010; Sereno & Lee, Reference Sereno and Lee2015). For example, Wiener et al. (Reference Wiener, Ito and Speer2018, Reference Wiener, Ito and Speer2021) conducted eye-tracking studies in which English-L1 speakers were trained on an artificial tonal language that mimics Mandarin’s syllable-tone combinations. Results indicate that both intermediate learners of Mandarin and naïve listeners used co-occurring tonal and segmental cues during spoken word recognition. Nevertheless, few studies have explicitly compared the difference between native and non-native speakers when learning Mandarin tones and segments, though findings from Cantonese learning may shed light on this question. For instance, Poltrock et al. (Reference Poltrock, Chen, Kwok, Cheung and Nazzi2018) found that native speakers learned Cantonese pseudowords better than non-native speakers; within the non-native group, Mandarin-L1 speakers outperformed their French-L1 counterparts in pseudowords that differed minimally in tones.

Homophony effects in lexical processing

Homophony is a common linguistic phenomenon, where pairs or groups of words have identical pronunciation but different meanings. However, the proportion of homophones varies across languages. It has been reported that 3.2% of English consists of homonyms (i.e., same pronunciation and spelling), whereas 11.6% of Mandarin is homophonous (Neergaard et al., Reference Neergaard, Xu, German and Huang2021; Wen, Reference Wen1980). According to Duanmu (Reference Duanmu2007), the average homophone density is 1.4 words per monosyllable in English (e.g., meat and meet), but five words per syllable in Mandarin. Some forms like shì (i.e., /ȿɻ4/ with the falling tone 4; the superscript number indicates the lexical tone of the syllable) correspond to nearly 30 unique homophonous morphemes (Wiener et al., Reference Wiener, Ito and Speer2018). An example of Mandarin disyllabic homophones is shǒushì /ȿo℧3ȿɻ4/, which has two meanings “gesture” (occurring 37 times in a corpus of five million words) and “jewelry” (occurring 44 times in the same corpus; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Huang, Chang and Hsu1996; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Chen, Gao, Chen and Shen1998).

Accordingly, different effects of homophony have been observed in English and Mandarin when processed by native speakers. For example, in lexical decision tasks, English homophones show longer response latencies and lower accuracy than non-homophones, especially among low-frequency words (Rubenstein et al., Reference Rubenstein, Lewis and Rubenstein1971). The size of homophony effects is found to be determined by the frequency of the homophone and its mate, as well as by the orthographic and phonological characteristics of the homophone (Pexman et al., Reference Pexman, Lupker and Jared2001). Contrarily, Mandarin homophones exhibit facilitative effects (i.e., faster processing than non-homophones; Ziegler et al., Reference Ziegler, Tan, Perry and Montant2000), which are also observed in non-native learners of Mandarin (Liu & Wiener, Reference Liu and Wiener2020, Reference Liu and Wiener2022). This homophony advantage is often attributed to the large amount of homophonic mates in Mandarin, which increases the phonological familiarity of a homophone and facilitates processing (Ziegler et al., Reference Ziegler, Tan, Perry and Montant2000).

To explore whether the distinct homophony effects in English and Mandarin can be explained by script type, Hino et al. (Reference Hino, Kusunose, Lupker and Jared2013) studied kanji, which are logographic Chinese characters used in Japanese writing. Native Japanese speakers showed an inhibitory effect for homophones with only one homophonic mate, but a facilitatory effect for those with multiple mates. Therefore, they concluded that the pattern is predicted by the number of homophonic mates that the target homophone has, rather than by the script type.

However, most studies in the previous literature focus on visual word recognition using the lexical decision task. Spoken language has received relatively less attention. Moreover, even though novel word learning was used in prior research, most work addresses homophony learning in infants and young children (Dautriche et al., Reference Dautriche, Chemla and Christophe2016, Reference Dautriche, Fibla, Fievet and Christophe2018; Ramachers et al., Reference Ramachers, Brouwer and Fikkert2017; Storkel & Maekawa, Reference Storkel and Maekawa2005). Yet until recently, some adult studies have examined non-native learning of spoken homophones in Mandarin. In Liu and Wiener (Reference Liu and Wiener2020, Reference Liu and Wiener2022), for example, native English speakers from a second-semester Mandarin class learned monosyllabic tonal pairs over three days. A facilitative homophone effect was observed when the talker variability was low. That is, new words that were homophonous with previously learned words were identified more accurately and recognized faster than those that were not homophonous, if learners were familiar with a single speaker’s voice.

Memory consolidation following learning

Studies have established sleep’s effects on memory enhancement after learning, when compared to an equivalent period of wakefulness (Diekelmann & Born, Reference Diekelmann and Born2010; Korman et al., Reference Korman, Doyon, Doljansky, Carrier, Dagan and Karni2007; Stickgold, Reference Stickgold2005). This benefit has also been validated in lexical learning research for English (Fenn et al., Reference Fenn, Nusbaum and Margoliash2003; Weighall et al., Reference Weighall, Henderson, Barr, Cairney and Gaskell2017) and Cantonese (Qin & Zhang, Reference Qin and Zhang2019). For example, Kurdziel and Spencer (Reference Kurdziel and Spencer2016) found that in a task of recalling novel words after a 12-hour delay that included sleep, English speakers outperformed their peers who spent the time awake. In terms of non-native tonal learning, Qin and Zhang (Reference Qin and Zhang2019) trained Mandarin listeners on identifying Cantonese tonal contrasts and found that those who had an overnight sleep between training and later post-tests showed improved performance in identification accuracy. Recently, Qin et al. (Reference Qin, Jin and Zhang2022) demonstrated that this overnight tone consolidation effect can be facilitated by a learner’s ability to detect pitch height differences.

Furthermore, even short periods of unoccupied rest can induce memory consolidation. Previous studies often categorize participants into two conditions: the waking rest condition where participants have an unoccupied rest and the distractor task condition where participants play a computer game. For instance, Brokaw et al. (Reference Brokaw, Tishler, Manceor, Hamilton, Gaulden, Parr and Wamsley2016) suggested that a 15-minute interval of waking rest can facilitate verbal declarative memory in a story recalling test, relative to playing a computer game as distraction (also see Humiston & Wamsley, Reference Humiston and Wamsley2018). Likewise, brief periods of wakeful resting enhance memory retention in a range of sensorimotor and cognitive tasks (Dewar et al., Reference Dewar, Alber, Butler, Cowan and Della Sala2012; Wamsley, Reference Wamsley2019). However, little research has addressed whether a 15-minute period of unoccupied rest can affect novel word learning, especially among learners from both native and non-native backgrounds.

The present study

The first aim of this study was to investigate the roles of phonology and homophony in Mandarin novel word learning among native and non-native (English) speakers. By combining different Mandarin tones and segments, we created a set of novel words that consisted of homophones and non-homophones and varied in types of phonological contrasts: consonant contrasts, tone contrasts, or both. To assess the time course of online processing after the learning, we tested novel spoken word recognition using the visual world paradigm, which allows for examining participants’ interpretation of linguistic stimuli without interruption (Dahan & Tanenhaus, Reference Dahan and Tanenhaus2005). The second aim was to explore whether brief periods of unoccupied rest would aid memory consolidation following the learning session. To this end, we designed the experiment with a break between the learning and test phases and compared the performance of participants who spent this interval either resting or gaming.

The novel word learning task consisted of three sections. The first one was an integrated Learning Phase/Test Phase I. In each trial, participants learned novel words via word-object associations and were then tested on the target word by selecting its matching object. The second section was a 15-minute break, during which participants either had an eyes-shut rest or played a computer game. The last section, Test Phase II, was a visual world eye-tracking experiment. Specifically, participants attended to three objects on a computer screen while listening to a novel word and selected the target object corresponding to what they heard. The target object was presented in two settings: in the competitor setting, it was presented with a competitor picture and a distractor picture; in the no-competitor setting, it was presented with two distractor pictures. Participants’ response accuracy in Test Phases I and II was collected, and their eye movements in Test Phase II were also analyzed.

We asked the following four research questions: (i) Do participants’ language backgrounds modulate their novel word learning outcome? Given that native speakers are familiar with the Mandarin phonological system and the task simulates their native word learning, we predicted that they would outperform non-native speakers overall, reflected by higher accuracy and more/earlier looks to the target object. (ii) Do phonological contrasts between novel words predict the outcome, and does this depend on participants’ language backgrounds? Considering previous evidence on the difficulty of tonal learning in non-native speakers (Chang & Bowles, Reference Chang and Bowles2015; Laméris & Post, Reference Laméris and Post2022), an interaction between phonological contrasts and language backgrounds was anticipated; in particular, English speakers would likely respond to novel words learned with tone contrasts least accurately. (iii) Is the learning outcome affected by the homophone status of novel words, and does this depend on participants’ language backgrounds? In light of different homophone effects in English (Pexman et al., Reference Pexman, Lupker and Jared2001; Rubenstein et al., Reference Rubenstein, Lewis and Rubenstein1971) and Mandarin (Ziegler et al., Reference Ziegler, Tan, Perry and Montant2000) as well as non-native speakers’ lack of Mandarin experience, it was predicted that homophony would interact with language backgrounds to affect the outcome, and a facilitative homophone effect may occur in native speakers only. (iv) Do different break types predict the outcome, and is this affected by participants’ language backgrounds? Since tonal learning can be consolidated overnight (Qin & Zhang, Reference Qin and Zhang2019; Qin et al., Reference Qin, Jin and Zhang2022) and brief periods of rest enhance memory as well (Brokaw et al., Reference Brokaw, Tishler, Manceor, Hamilton, Gaulden, Parr and Wamsley2016; Dewar et al., Reference Dewar, Alber, Butler, Cowan and Della Sala2012; Wamsley, Reference Wamsley2019), it was hypothesized that participants who had a rest would outperform those who played the game, regardless of their language backgrounds.

Method

Participants

We recruited 68 adults via an online participant pool or flyers at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada: 67 were students who participated in exchange for course credits, and one was an employee who received a small payment. Four native English speakers were excluded due to previous experience with Mandarin and/or Japanese, considering that the pitch features of Japanese may assist Mandarin tone learning (Caldwell-Harris et al., Reference Caldwell-Harris, Lancaster, Ladd, Dediu and Christiansen2015; So & Best, Reference So and Best2010). Therefore, a total of 64 participants were included in the final analysis: 34 native Mandarin speakers who were from mainland China (25 female; M age = 20.5 years, range = 18–27, SD = 1.86), and 30 native English speakers who were from Canada and without tonal language background or experience (21 female; M age = 22.9 years, range = 18–63, SD = 9.86). While an a priori power analysis was not performed, the sample size of each language group in the current study was largely comparable to that reported in previous research (Brokaw et al., Reference Brokaw, Tishler, Manceor, Hamilton, Gaulden, Parr and Wamsley2016; Poltrock et al., Reference Poltrock, Chen, Kwok, Cheung and Nazzi2018; Qin & Zhang, Reference Qin and Zhang2019; Ziegler et al., Reference Ziegler, Tan, Perry and Montant2000).

Given the facilitative effects of musicality on linguistic tone learning (Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Wong and Bradlow2005; Wong & Perrachione, Reference Wong and Perrachione2007), we collected information about participants’ musical background using the Goldsmiths Musical Sophistication Index, which consists of five dimensions: active engagements, perceptual abilities, musical training, singing abilities, and emotions (i.e., emotional responses to music; Müllensiefen et al., Reference Müllensiefen, Gingras, Musil and Stewart2014). This index was included as a variable of interest in statistical modeling. All participants reported normal or corrected-to-normal vision and normal hearing and gave written informed consent prior to participation. The experiment protocol and consent procedures were reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Board of the University of Alberta.

Materials

Novel words

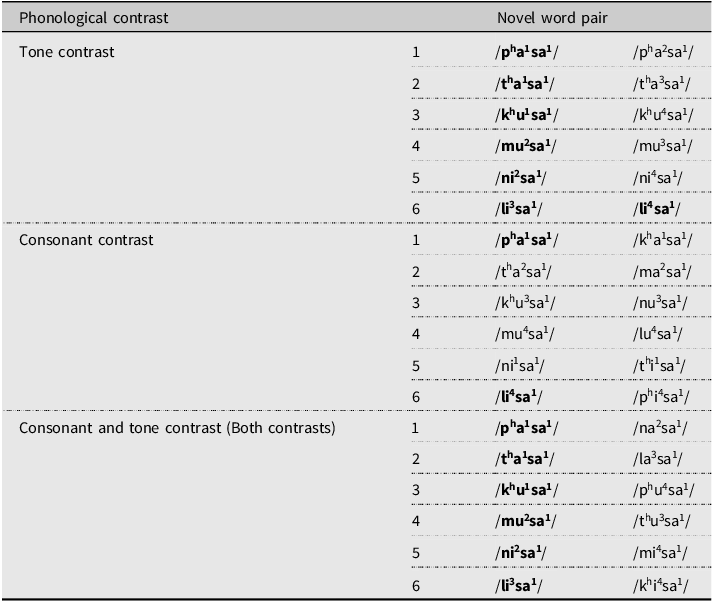

We created 18 pairs of Mandarin disyllabic novel words (see Table 1). The first syllables were generated by integrating the six consonants /ph, th, kh, m, n, l/, three vowels /a, u, i/, and four lexical tones in Mandarin, whereas the second syllables were constantly /sa1/. We avoided phonological combinations that are real words in Mandarin (i.e., existing Mandarin disyllabic words were not used). Thus, 28 novel words were created, of which seven (25%) are homophones: /tha1sa1/, /khu1sa1/, /mu2sa1/, /ni2sa1/, /li3sa1/, /li4sa1/, and /pha1sa1/. We were not interested in controlling potential frequency effects; participants encountered phonological forms of homophones more often than those of non-homophones since they learned homophonous forms with two (for /pha1sa1/, three) different meanings.

Table 1. Mandarin novel words

Note. Novel words in bold are homophones.

There are three phonological contrast groups. First, pairs in the tone contrast group differ in the first syllables’ tones only, representing all six possible tonal comparisons in Mandarin (i.e., tone 1/tone 2, tone 1/tone 3, tone 1/tone 4, tone 2/tone 3, tone 2/tone 4, tone 3/tone 4). Second, novel words in the consonant contrast group differ in the first syllables’ consonants only. To even out the number of pairs in each group, tones 1 and 4 were used more than once in this group because they are less difficult than the other two tones for native English speakers (Chang & Bowles, Reference Chang and Bowles2015). Third, the consonant and tone contrast (hereafter referred to as both contrasts) group incorporates segmental and tonal differences within the first syllables.

Further, another two novel words /musa/ and /thusa/, carrying the Mandarin neutral tone in both syllables, were created for the practice trial. The first author, a native Mandarin speaker from northern China, recorded all novel words in a sound-attenuated booth and manually split them into separate sound files using Praat (Boersma & Weenink, Reference Boersma and Weenink2020).

Novel objects

From the Novel Object and Unusual Name Database (Horst & Hout, Reference Horst and Hout2016), we selected 47 novel objects that control for complexity in color, shape, and material. These objects were randomly assigned to the created novel words for participants to learn (see Appendix A in Supplementary Materials for a list of the word-object mappings). Except for the two objects in the practice trial, all were used in experimental trials: 36 as target or competitor objects and nine as distractor objects (see Appendix B in Supplementary Materials for a list of the distractor objects).

Procedure

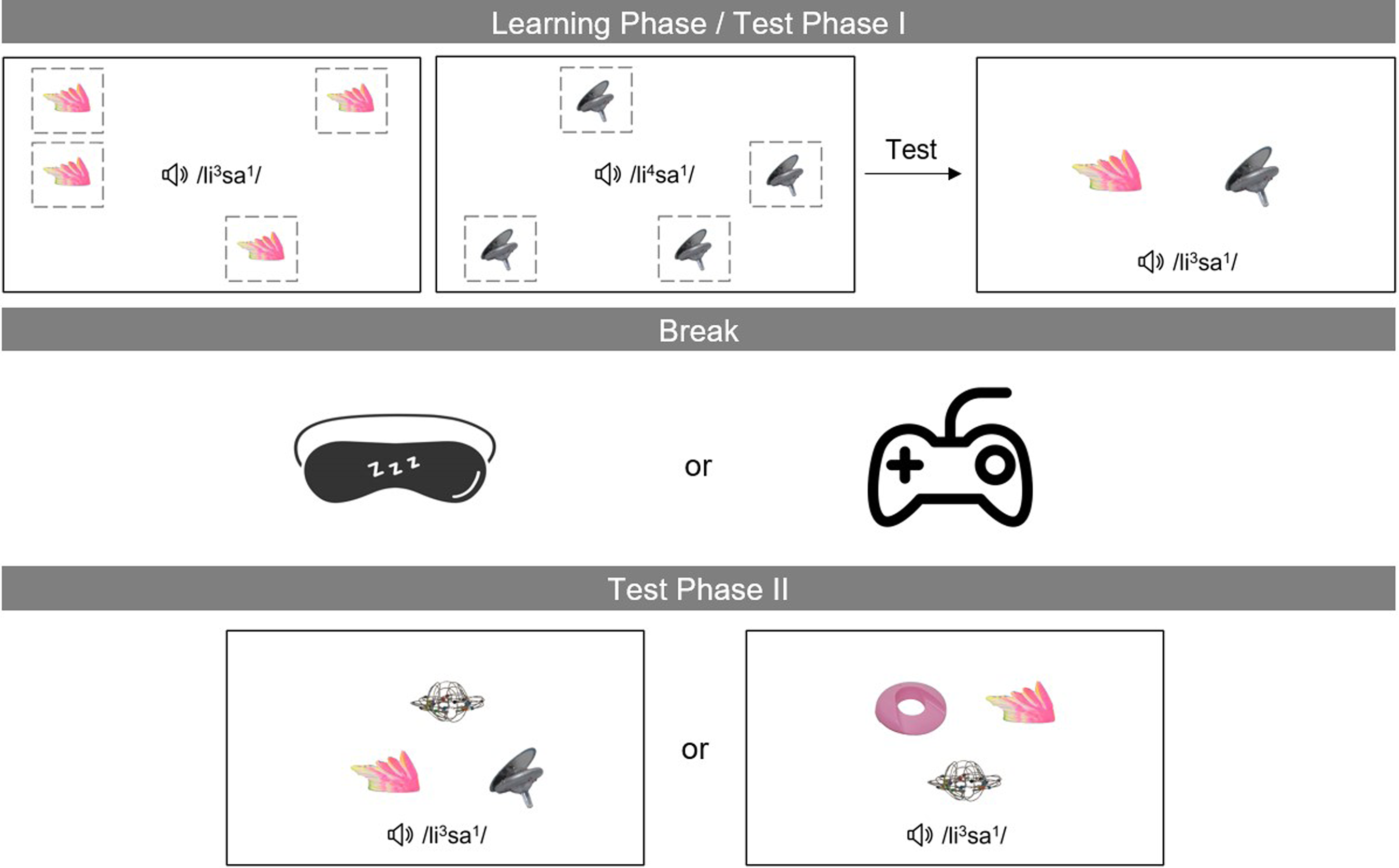

Each experimental session was composed of three sections, as illustrated in Figure 1: the integrated Learning Phase/Test Phase I, Break, and Test Phase II. It took approximately 35 minutes to complete the whole session.

Figure 1. Novel word learning task.

Note. The task consisted of three sections: Learning Phase/Test Phase I, Break, and Test Phase II. During the integrated Learning Phase/Test Phase I, participants learned pairs of novel words (e.g., /li3sa1/ and /li4sa1/; the glosses illustrate novel words played auditorily and did not appear on the screen during the experiment) and then tested on one of them (e.g., /li3sa1/). Afterward, there was a 15-min break when participants either had an eyes-shut rest or played a game. In Test Phase II, participants were tested on one of the novel words (e.g., /li3sa1/) again, which was presented either with its competitor (/li4sa1/) and a distractor (i.e., the competitor setting on the left) or with two distractors (i.e., the no-competitor setting on the right).

Learning Phase/Test Phase I

In each trial, participants learned one of the 18 pairs of novel words and then tested on one of them (cf. Figure 1). During the learning, a novel object randomly appeared at four different locations on a display screen (24 inches, 1,920 × 1,080 pixel resolution), with its name (i.e., the novel word) presented auditorily twice at each place. Then, the second object went through the same process. Thereby, within each trial, participants were presented with the novel word/object 8 times (4 visual displays × 2 audio plays). During the test, the two novel objects simultaneously appeared at the center of the screen, but only one novel word was played. By pulling one of the two triggers on a gamepad, participants matched the novel word they heard to its corresponding object. Within the paired novel words, the tested one was labeled as the target (referring to the target object) and the other one as the competitor (referring to the competitor object). No feedback was given to participants after they responded.

This section was programmed with Experiment Builder (SR Research, 2015). Participants’ eye movements were tracked with an SR Research EyeLink 1000 desktop mount eye tracker, which was run on a Dell PC with a sampling rate of either 500 Hz or 1,000 Hz. There was one practice trial for participants to familiarize themselves with the task, followed by 18 experimental trials (see Appendix C in Supplementary Materials). It took around 10 minutes to complete this section. We collected participants’ responses and eye movements, but only analyzed the former.

Break

During the break, participants were randomly assigned to either the game or the rest group. In the game group, participants played the computer game “Snood” as a distractor task for 15 minutes. In this game, players clear blocks of colors by joining three or more icons of the same color. It was chosen because the game is engaging and involves only minimal hand and eye movements. In the rest group, participants wore an eye mask while sitting back or lying down on a reclining chair and had an eyes-closed rest for the same duration.

Test Phase II

At each trial, three novel objects simultaneously appeared on the screen, some of which had occurred before; the name of one of them (i.e., the target word) was played auditorily, while participants’ eye gaze to the presented pictures was tracked. The target object was presented in two settings, either with or without its competitor. Specifically, in the competitor setting, the target object occurred with its competitor and one unrelated distractor object; in the no-competitor setting, the target object appeared with two unrelated distractor objects that participants had not encountered during the learning. Participants were instructed to use the computer mouse to click on the target object that matched the spoken novel word they heard. No feedback was provided after their responses.

This section was programmed with Experiment Builder (SR Research, 2015) as well, and participants’ eye movements were recorded using the same eye tracker. Since each novel word (cf. Table 1) served once as the target and once as the competitor, there were altogether 72 trials (18 novel word pairs × 2 targets × 2 competition settings; see Appendix D in Supplementary Materials for a list of the 72 trials). It took around 10 minutes to complete this section. We collected and analyzed participants’ response and eye movement data.

Data analysis

Response data

We analyzed response accuracy in Test Phases I and II. Using the lme4 package (v1.1-28; Bates et al., Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015), we built generalized linear mixed-effects models in R (v4.1.1; R Core Team, 2021). Estimated p-values were obtained through the lmerTest package (v3.1-3; Kuznetsova et al., Reference Kuznetsova, Brockhoff and Christensen2017). The dependent variable was Accuracy, which was coded as a binary variable (Correct vs. Incorrect). Accordingly, we specified the family argument as binomial in model construction. For fixed effects, the independent variables consisted of Language Background (Native Mandarin vs. Native English), Homophony (Homophone vs. Non-homophone), Phonological Contrast (Consonant Contrast vs. Tone Contrast vs. Both Contrasts), and Musical Sophistication (Active Engagements vs. Perceptual Abilities vs. Musical Training vs. Singing Abilities vs. Emotions) in Test Phase I, as well as another two: Break Type (Rest vs. Game) and Competition (Competitor vs. No-competitor) in Test Phase II. For random effects, we included random intercepts for Subject and Word and tested random slopes for all of the manipulated factors mentioned above.

To attain the optimal model, fixed-effects and random-effects structures were fitted separately using a stepwise backward approach. Specifically, we used the anova function to compare a complex model to its simpler version which had one component removed, by inspecting the estimated p-value and Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) value. The complex model was favored only when the difference was significant as indicated by the p-value (smaller than the conventional alpha level of 0.05) and when it provided a better fit for the data as indicated by the AIC value. Otherwise, we selected the simpler model (Matuschek et al., Reference Matuschek, Kliegl, Vasishth, Baayen and Bates2017). After the optimal model was determined, we used the emmeans package (v1.7.2; Lenth, Reference Lenth2022) to conduct multiple comparisons for significant factors and interactions and applied the Tukey adjustment method to guard against Type I error. We report significant comparisons (p < 0.05) below.

To visualize data, Accuracy was converted to a numeric variable as Accuracy Proportion. Effects of significant factors and interactions were visualized using the ggplot2 (v3.3.5; Wickham, Reference Wickham2016) and lattice (v0.20-45; Sarkar, Reference Sarkar2008) packages. To indicate significant group differences on the graphics, the ggsignif package (v0.6.3; Constantin & Patil, Reference Constantin and Patil2021) was used.

Eye movement data

Eye movements in Test Phase II only were analyzed. For preprocessing, data were output as a sample report using the SR Research EyeLink Data Viewer and then preprocessed using the VWPre package (v1.2.4; Porretta et al., Reference Porretta, Kyröläinen, van Rij and Järvikivi2016). To index each unique recording sequence of eye movements, Event was created as a combination of Subject and Trial. Prior to binning the data, we identified events with excessive trackloss. Specifically, 171 events (3.71%) were detected with more than 25% trackloss data and thus were removed. We were only interested in eye fixations that occurred in the target interest area (i.e., target looks). In order to obtain proportion looks, we aggregated the sample data into 20 ms bins, and each bin was coded as Target or Nontarget. Since proportions are not suitable for analysis, empirical logits (Barr, Reference Barr2008) were calculated for the binned target proportion data, within the time window from 200 to 1,700 ms after the target stimulus onset. We used 200 ms as the starting point because it usually takes around that duration of time to program a saccade and execute an eye movement (Fischer, Reference Fischer and Rayner1992).

Using the mgcv package (v1.8-39; Wood, Reference Wood2017), we built generalized additive mixed-effects models (GAMMs), as they are well designed for analyzing time series data (Baayen et al., Reference Baayen, van Rij, de Cat, Wood, Speelman, Heylen and Geeraerts2017). Eye movements in the correct trials (n = 3,304) only were modeled. The dependent variable was the logit-transformed proportions of target looks. The independent variables were the same as those in the accuracy analysis. The fixed-effects structure consisted of a significant predictor and its nonlinear interaction with time (i.e., smooth). The random-effects structure contained a random intercept for Event, a random smooth for Subject by time, and a random smooth for Word by time.

The fixed-effects and random-effects structures were fitted separately in a stepwise forward manner. Specifically, we employed the maximum likelihood (ML) estimation approach for model comparisons, through the compareML function in the itsadug package (v2.4; van Rij et al., Reference van Rij, Wieling, Baayen and van Rijn2020). The contribution of a new component was evaluated based on the estimated p-value obtained from comparing the models’ ML scores, and the component was included only when the p-value was smaller than the conventional threshold of 0.05. After the model structure was determined, considering possible autocorrelation, an AR(1) (i.e., first-order autoregression) model for the residuals was constructed by specifying the rho parameter and the starting point for each time series to account for the fact that each value in a time series is affected by the preceding value.

In terms of data visualization, averaged proportion looks to different interest areas were plotted using the VWPre package (v1.2.4; Porretta et al., Reference Porretta, Kyröläinen, van Rij and Järvikivi2016). Additionally, as the summary of GAMMs does not indicate the exact shape of regression lines and whether they differ from each other significantly, we used the itsadug package (v2.4; van Rij et al., Reference van Rij, Wieling, Baayen and van Rijn2020) to plot the nonlinear smooths and significant difference curves.

Results

There were neither significant effects of musical sophistication on participants’ performance, nor did the Mandarin and English speaker groups differ significantly with respect to musical sophistication. Thus, we do not further discuss this factor in the rest of the paper.

Response accuracy

Test Phase I

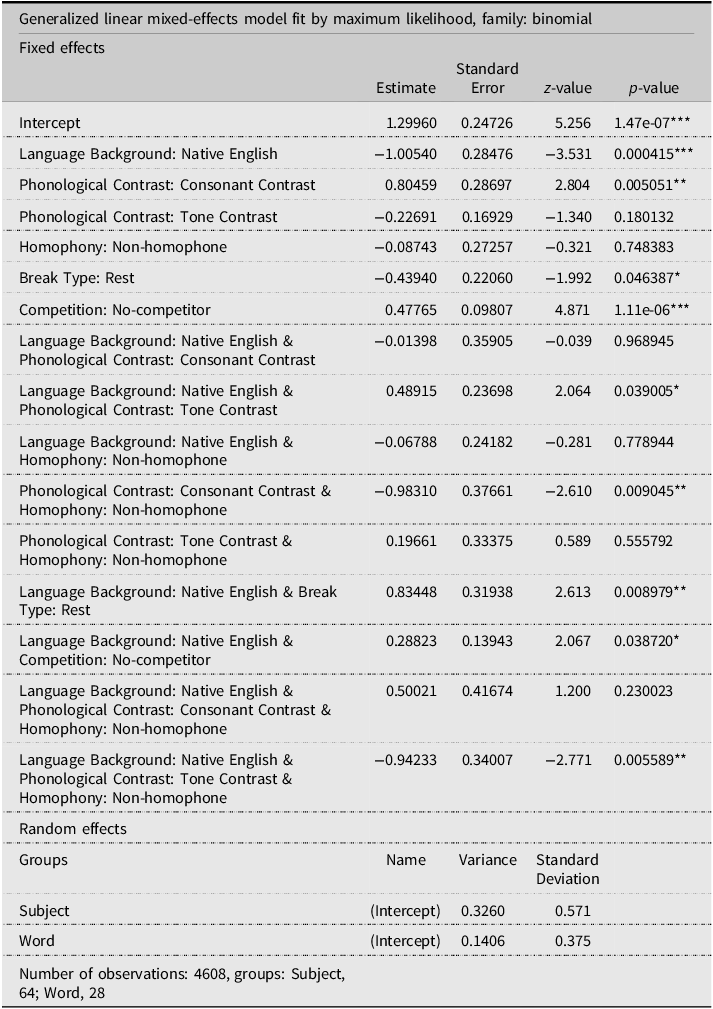

There were 1,152 trials (64 participants × 18 trials). Model comparisons suggested that Language Background (p < 0.001) and Phonological Contrast (p = 0.021) affected response accuracy, whereas Homophony did not (p = 0.908); no significant interaction was found among the three factors. The random-effects structure consisted of random intercepts for Subject and Word, as adding random slopes did not improve the model fit. A summary of the optimal model is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Model summary: Accuracy in Test Phase I

Note. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

For the significant effects, multiple comparisons indicated that Mandarin speakers had significantly higher accuracy than English speakers (p = 0.0001; see Figure 2 left panel). Mandarin speakers achieved near-ceiling performance (98.5% mean accuracy), probably because this test phase occurred right after the learning. Further, novel words learned in pairs with both contrasts received significantly more correct responses than those learned in pairs with tone contrasts only (p = 0.028; see Figure 2 right panel). In the consonant contrast condition, accuracy was slightly lower than the both contrasts condition and higher than the tone contrast condition, but neither difference reached the significance level.

Figure 2. Significant effects on accuracy in Test Phase I.

Note. Left and right panels show the effects of Language Background and Phonological Contrast on accuracy proportions (y-axis), respectively. Error bars represent the standard error of mean; asterisks indicate a significant difference (*p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001).

Test Phase II

There were 4,608 trials (64 participants × 72 trials). In the final model, the fixed-effects structure consisted of three significant interactions: a three-way interaction among Language Background, Phonological Contrast, and Homophony (p < 0.001); an interaction between Language Background and Break Type (p = 0.011); and an interaction between Language Background and Competition (p = 0.040). The random effects included only random intercepts for Subject and Word, since none of the random slopes improved model performance. A summary of the best model is shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Model summary: Accuracy in Test Phase II

Note. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Figure 3 displays the effects of these significant interactions. Panel (a) shows the three-way interaction among Language Background, Phonological Contrast, and Homophony. Multiple comparisons suggested that when learning non-homophones in pairs with tone contrasts, English speakers had significantly lower accuracy than Mandarin speakers (p = 0.002). Within Mandarin speakers, homophones presented in pairs with consonant contrasts received significantly higher accuracy than those presented in pairs with tone contracts (p = 0.007), and for words learned in pairs with consonant contrasts, homophones were significantly more accurate than non-homophones (p = 0.042). Surprisingly, Mandarin speakers had lower accuracy than English speakers when learning homophones with tonal contrasts, though this difference did not reach the significance level. Panel (b) illustrates the interaction between Language Background and Break Type. Interestingly, English speakers had higher accuracy after resting, whereas Mandarin speakers achieved better results after gaming; yet neither of these differences between resting and gaming was significant. However, after playing the game, Mandarin speakers performed significantly better than English speakers (p = 0.002). In addition, the interaction between Language Background and Competition is presented in panel (c). The no-competitor setting had significantly higher accuracy than the competitor setting in both language groups (Mandarin, p < 0.001; English, p < 0.001), although Mandarin speakers outperformed English speakers in the competitor setting (p = 0.012).

Figure 3. Significant effects on accuracy in Test Phase II.

Note. Panel (a) presents the significant three-way interaction among Language Background (x-axis), Phonological Contrast, and Homophony; (b) presents the interaction between Language Background and Break Type (x-axis); (c) presents the interaction between Language Background and Competition (x-axis). Across panels, y-axis indicates accuracy proportions and error bars represent the standard error of mean.

Eye movements

Eye movement data in Test Phase II consisted of 4,608 events (64 participants × 72 trials). After removing the 171 events identified with more than 25% trackloss data, the remaining dataset contained 326,599 observations. Then, we focused on data with correct responses, which resulted in a total of 232,564 observations.

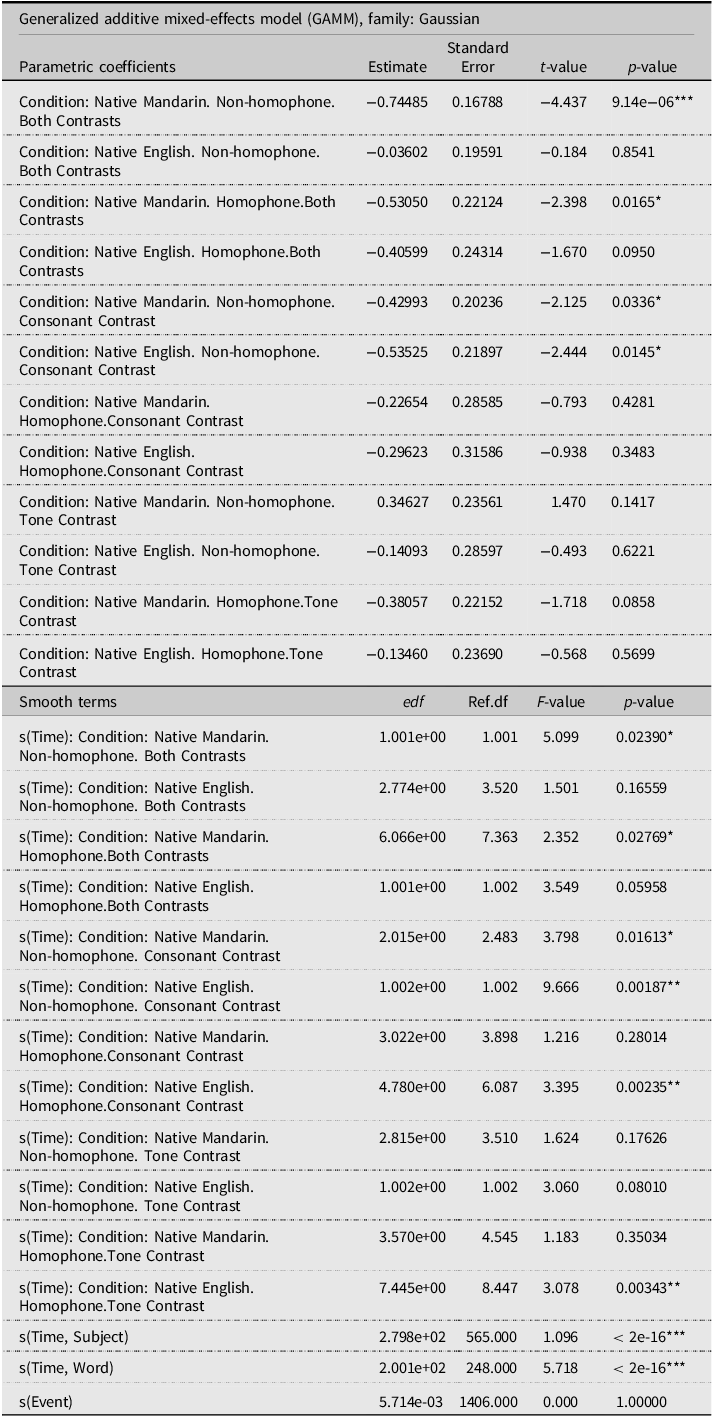

For GAMMs analysis, we generated empirical logits of the binned target proportion data from 200 ms after the target stimulus onset until 1,700 ms, which served as the dependent variable. The random-effects structure contained a random intercept for Event, a random smooth for Subject by time, and a random smooth for Word by time. For the fixed-effects structure, model comparison suggested a significant three-way interaction among Language Background, Phonological Contrast, and Homophony (p < 0.001). In order to inspect the effect of time on this interaction, the three factors were concatenated as a new variable Condition with 12 (2 × 3 × 2) levels. A smooth term indicating its nonlinear interaction with time was also significant (p < 0.001). Moreover, model selection revealed a significant interaction between Condition and Competition (p < 0.001). This was further evidenced by visualizing the averaged proportions of target looks in different conditions for the competitor and no-competitor settings (see Appendix E in Supplementary Materials). Therefore, we analyzed how Condition affected target looks over time in the two settings separately.

The competitor setting contained 106,774 observations. A summary of the optimal model is presented in Table 4. According to the smooth terms section, a significant nonlinear curve over time was found for six levels of Condition, as shown by the edf (i.e., effective degrees of freedom) value greater than 1 (indicating wiggliness) and the p-value lower than 0.05. These nonlinear smooths were plotted in Figure 4. Different patterns were found between the two language groups: overall, target looks increased over time in Mandarin speakers but fluctuated in English speakers.

Table 4. Model summary: Logit-transformed proportions of target looks in the competitor setting

Note. edf : effective degrees of freedom; Ref.df: reference degrees of freedom; ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Figure 4. Significant nonlinear smooths over time in the competitor setting.

Note. The x-axis indicates the time after the target stimulus onset, from 200 to 1,700 ms; the y-axis indicates logit-transformed proportions of target looks. Each curve represents a nonlinear smooth, and the shaded area indicates 95% confidence interval. Left panel shows nonlinear smooths for Mandarin speakers. Black curve: non-homophones learned in pairs with consonant contrasts; light gray curve: non-homophones learned in pairs with both contrasts; dark gray curve: homophones learned in pairs with both contrasts. Right panel shows nonlinear smooths for English speakers. Black curve: non-homophones learned in pairs with consonant contrasts; light slate gray curve: homophones learned in pairs with tone contrasts; dark slate gray curve: homophones learned in pairs with consonant contrasts.

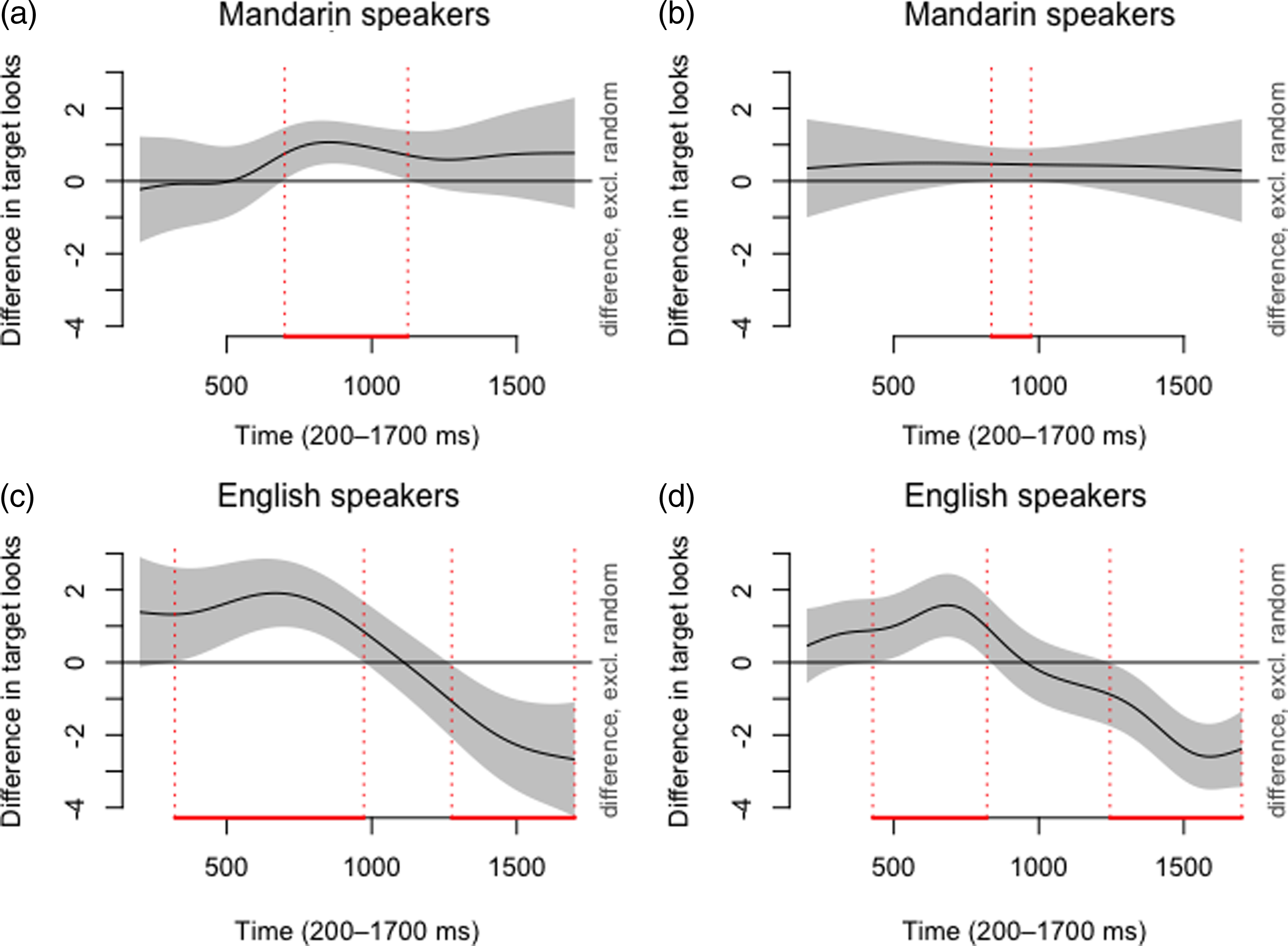

Further, significant difference curves are illustrated in Figure 5. Among Mandarin speakers, non-homophones generally received more target looks than homophones when learned in pairs with both contrasts, with a significant difference from 700 to 1,124 ms (see panel a); non-homophones learned in pairs with both contrasts had more target looks continuously than those with consonant contrasts, with a brief period (836–973 ms) showing a significant difference (panel b). Among English speakers, in the consonant contrast environment, homophones received significantly more target looks than non-homophones within 321–973 ms, though the latter had more target looks from 1,276 ms to the end (panel c); homophones learned in pairs with consonant contrasts received significantly more target looks in 427–821 ms, but less from 1,245 ms until the end, compared to those with tone contrasts (panel d). In summary, where differences occurred, Mandarin speakers showed more looks to non-homophones than to homophones learned in the same conditions, whereas it was the other way around for English speakers. Additionally, the data provide some evidence that consonant contrasts facilitate early target identification compared to tone contrasts for English speakers.

Figure 5. Significant difference curves in the competitor setting.

Note. The x-axis indicates the time after the target stimulus onset, from 200 to 1,700 ms; the y-axis indicates the difference in logit-transformed proportions of target looks. For each curve, the red interval (with vertical dotted lines) indicates the time window with a significant difference. The shaded area indicates 95% confidence interval. Panel (a) compares non-homophones and homophones learned in pairs with both contrasts by Mandarin speakers, with a significant difference within 700–1,124 ms. Panel (b) compares consonant contrasts and both contrasts in non-homophones learned by Mandarin speakers, with a significant difference in 836–973 ms. Panel (c) compares homophones and non-homophones learned in pairs with consonant contrasts by English speakers, with significant differences within 321–973 ms and 1,276–1,700 ms. Panel (d) compares consonant contrasts and tone contrasts in homophones learned by English speakers, with significant differences within 427–821 ms and 1,245–1,700 ms.

The no-competitor setting consisted of 125,790 observations. Table 5 presents a summary of the final model. The smooth terms section suggests two nonlinear curves with significant changes over time for Condition, both in English speakers, which were plotted in the left panel of Figure 6; the right panel shows the significant differences between these curves. Specifically, we observed a similar pattern as in the competitor setting: among English speakers, homophones learned in pairs with consonant contrasts received significantly more target looks than those with tone contrasts from 609 to 1,033 ms, but less from 1,579 ms until the end. However, there were no significant nonlinear curves found in Mandarin speakers.

Table 5. Model summary: Logit-transformed proportions of target looks in the no-competitor setting

Note. edf : effective degrees of freedom; Ref.df: reference degrees of freedom; ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Figure 6. Significant nonlinear smooths and difference curve in the no-competitor setting.

Note. Left panel shows two significant nonlinear smooths, both found in English speakers. The x-axis indicates the time after the target stimulus onset, from 200 to 1,700 ms; the y-axis indicates logit-transformed proportions of target looks. Each curve represents a nonlinear smooth, and the shaded area indicates 95% confidence interval. Black curve: homophones learned in pairs with consonant contrasts; dark gray curve: homophones learned in pairs with tone contrasts. Right panel shows the significant difference curve. It compares consonant contrasts and tone contrasts in homophones learned by English speakers, with significant differences within 609–1,033 ms and 1,579–1,700 ms.

Discussion

This study used the visual world eye-tracking paradigm to explore how adults from native and non-native backgrounds learn Mandarin novel words, which had homophones and non-homophones and varied in types of phonological contrasts: consonant contrasts, tone contrasts, or both. We also examined if brief periods of unoccupied rest would affect participants’ learning outcome. In Test Phase I, which occurred immediately after the learning, accuracy results show near-ceiling performance, with Mandarin speakers outperforming English speakers. In Test Phase II, which occurred after a 15-minute break, several significant interactions among the manipulated factors were observed, and Mandarin speakers only outperformed English speakers under certain circumstances. Further, eye movement findings reveal that segmental and tonal information may contribute differently to novel spoken word recognition.

Language background effects

We first asked whether participants’ language backgrounds would modulate their novel word learning outcome and predicted that native speakers would outperform non-native speakers in general. In Test Phase I, this hypothesis was borne out, as Mandarin speakers had significantly higher accuracy than English speakers. This result suggests that Mandarin speakers possessed an advantage due to their native phonological knowledge, which is in line with Poltrock et al. (Reference Poltrock, Chen, Kwok, Cheung and Nazzi2018) who found that native speakers performed better than non-native (Mandarin-L1 and French-L1) speakers when learning Cantonese novel words.

In Test Phase II, however, the picture becomes more complicated. Participants’ language backgrounds interacted with phonology and homophony to affect the accuracy measure. Although English speakers were generally less accurate than Mandarin speakers, the group difference was only significant when learning non-homophones in pairs with tone contrasts (see further discussion in the following sections). Thus, the language background effects here should be interpreted within the context, where participants were tested on novel words learned a short period of time before. That said, our results provide further evidence for the relative difficulty of tonal learning in adult non-native speakers (in line with Hao, Reference Hao2018; Laméris & Post, Reference Laméris and Post2022; Pelzl, Reference Pelzl2019).

In addition, eye-tracking data showed some patterns unique to English speakers. For example, when comparing homophones learned in different phonological environments, English speakers had more target looks to those learned in the consonant contrast condition during an early stage, but more target looks to those learned in the tone contrast condition later. This result indicates that English speakers were able to use not only the segmental information but also tonal cues in novel word recognition (in line with Wiener et al., Reference Wiener, Ito and Speer2018, Reference Wiener, Ito and Speer2021), although the latter seems to be less straightforward and readily accessible. It is possible that the later effect of tonal contrasts is simply due to the fact that tonal cues appear mainly on vowels, i.e., later than consonantal ones, which were localized to syllable onsets (Cutler and Chen, Reference Cutler and Chen1997; Ling and Grüter, Reference Ling and Grüter2022, but also see Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Guo, Zhou and Shu2011; Zou et al., Reference Zou, Caspers and Chen2022). Yet more evidence is needed to verify this inference, for example, by comparing the learning of novel words starting with or without an initial consonant. Overall, our findings suggest that beyond accuracy, participants’ language backgrounds affected their eye movement behavior, which demonstrates differences in online language processing.

Phonology effects

We also examined whether different types of phonological contrasts entailed in the novel word pairs would predict the outcome and whether this would depend on participants’ language backgrounds. In Test Phase I, different from our hypothesis, there was a significant effect of phonological contrasts on accuracy, but no interaction with language backgrounds. Specifically, across language groups, novel words learned in pairs with both contrasts received significantly higher accuracy than those with tone contrasts only. This finding can be explained in part by the fact that the coexistence of segmental and tonal distinctions facilitates novel word recognition and learning simply due to the availability of two cues rather than just one. Further, tonal contrasts not only are difficult to learn for native English speakers (Hao, Reference Hao2018; Pelzl et al., Reference Pelzl, Lau, Guo and DeKeyser2019) but also may pose a challenge for native Mandarin speakers to identify or process (Taft & Chen, Reference Taft, Chen, Chen and Tzeng1992; Ye & Connine, Reference Ye and Connine1999). For example, Taft and Chen (Reference Taft, Chen, Chen and Tzeng1992) found that native Mandarin speakers had significantly longer reaction latency and higher error rates when discriminating word pairs that differed in tones than those differed in vowels. Similarly, Ye and Connine (Reference Ye and Connine1999) reported faster reaction time when listening to Mandarin syllables mismatched on vowels than those mismatched on tones among native speakers. It has been suggested that tones may be a weaker cue than segments in Mandarin lexical access, because tones are primarily realized on vowels and thus are available later than segments in CV syllables (Cutler & Chen, Reference Cutler and Chen1997; Ling & Grüter, Reference Ling and Grüter2022). Yet, there are studies showing parallel processing of tonal and segmental information in Mandarin word recognition (Malins & Joanisse, Reference Malins and Joanisse2010, Reference Malins and Joanisse2012; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Guo, Zhou and Shu2011; Zou et al., Reference Zou, Caspers and Chen2022). From another perspective, it can also be hypothesized that tones provide fewer cues than segments since each tone is associated with far more lexical entries than each segment is. Ultimately, it is possible that these inherent differences may account for some of the differences we observed in the learning of novel words that contrast in Mandarin tones and segments (and their combinations).

In Test Phase II, also different from what we expected, phonological contrasts interacted with language backgrounds and homophony to influence accuracy. As stated above, Mandarin speakers outperformed English speakers when learning non-homophones in pairs with tone contrasts; however, surprisingly, they did not outperform English speakers in all other conditions. Further, within Mandarin speakers, homophones learned in pairs with consonant contrasts received more accurate responses than those with tone contrasts. In other words, tonal information complicates Mandarin homophone learning, especially in native speakers. This might be due to a less informative role of tones in Mandarin word retrieval than segments, and a larger interference from their mental lexicon in native speakers than non-native speakers. A further study could assess other tonal language speakers with a different phonology (e.g., Cantonese speakers who have a more complex tonal system) and consider vowel contrasts to compare learners’ performance on specific segments and tones.

Homophony effects

We investigated whether the homophone status of a novel word would affect the learning outcome and whether this would be dependent on participants’ language backgrounds. We predicted that homophony would interact with language backgrounds. However, this was not the case in Test Phase I, as we did not find any homophony effects on accuracy. By contrast, in Test Phase II, homophony and language backgrounds participated in a three-way interaction. For Mandarin speakers, homophones received more accurate responses than non-homophones when novel words were learned in pairs with consonant contrasts. Though a significant difference only appeared in this particular phonological condition, it is in line with previous research showing a facilitative effect of homophony on processing in Mandarin (Ziegler et al., Reference Ziegler, Tan, Perry and Montant2000). Nonetheless, this facilitative effect was not observed in English speakers at all, which is different from the findings of Liu and Wiener (Reference Liu and Wiener2020, Reference Liu and Wiener2022). A possible explanation could be that the English speakers in our study did not have any tonal language experience, whereas those in Liu and Wiener (Reference Liu and Wiener2020, Reference Liu and Wiener2022) had learned Mandarin for at least several months.

Since previous research has mainly used lexical decision tasks to explore different homophone effects in Mandarin and English (e.g., Ziegler et al., Reference Ziegler, Tan, Perry and Montant2000), our study is the first empirical investigation of homophony in Mandarin novel word learning among native and non-native adults. Importantly, our results demonstrate that the phonological information embedded in Mandarin homophones can interact with listeners’ language backgrounds to modulate their learning outcome. In particular, English speakers did not profit from homophony when learning Mandarin novel words in terms of the accuracy they achieved, though they did show more early target looks in homophones compared to non-homophones when presented with a competitor differing in a consonant. Whether the absence of a clear facilitative effect is due to the lower proportion of homophones and the inhibitory effect associated with homophones in English (Pexman et al., Reference Pexman, Lupker and Jared2001; Rubenstein et al., Reference Rubenstein, Lewis and Rubenstein1971) or to these participants being non-native speakers without experience with tonal languages is a matter for future research.

Rest effects

Lastly, we asked if different types of break would predict the learning outcome and whether this would be contingent on participants’ language backgrounds. Our hypothesis was that the rest group would perform better than the game group, irrespective of language backgrounds, based on previous research showing the benefits of sleep or rest in various tasks (Brokaw et al., Reference Brokaw, Tishler, Manceor, Hamilton, Gaulden, Parr and Wamsley2016; Dewar et al., Reference Dewar, Alber, Butler, Cowan and Della Sala2012; Kurdziel & Spencer, Reference Kurdziel and Spencer2016; Qin & Zhang, Reference Qin and Zhang2019; Wamsley, Reference Wamsley2019). However, this was not corroborated. We found that participants’ break type interacted with their language backgrounds, with different patterns in the two language groups. Interestingly, Mandarin speakers benefited from spending the break gaming, whereas English speakers performed better after resting, though the difference between resting and gaming was not significant within either language group. However, Mandarin speakers outperformed English speakers in the gaming condition, but not in the rest condition. Thus, the present study only provides limited statistical evidence for an effect of break type. This might be attributed to the difficulty of the task or the duration of the rest, which raises questions for future research about the role of rest in novel word learning. Nevertheless, to our knowledge, this is the first study addressing how brief periods of rest affect novel word learning in both native and non-native adult speakers.

Limitations

One limitation of our design lies in the number of investigated factors, which have led to the complexity of statistical models and undermined the statistical power, especially considering the relatively limited sample size. We addressed multiple questions related to adult novel word learning in the current study, and most of these questions are complicated by themselves. Future work could examine them more closely by focusing on one or two factors or having a larger sample size. In addition, we acknowledge the exploratory nature of the question about rest. Despite recent research on sleep-dependent consolidation of learning non-native tones (Qin & Zhang, Reference Qin and Zhang2019; Qin et al., Reference Qin, Jin and Zhang2022), the role of a short period of rest was not explored yet, which was the motivation and novelty of our work. Nevertheless, different from our expectation, the rest interacted with linguistic factors even though they may seem loosely related to each other. Thus, a future study could take another approach to analyze their association further, for example, by first examining the rest effects in Mandarin novel word learning and then extending to learning tones and segments, and lastly comparing native and non-native speakers.

Conclusions

Using visual world eye-tracking, this study is the first comprehensive investigation of Mandarin novel word learning in adult native and non-native speakers. We integrated two fundamental features of Mandarin, phonology and homophony, and assessed the effects of rest following lexical learning. Notably, these linguistic and non-linguistic variables interacted with the learner’s language backgrounds to affect their learning outcome. For example, native speakers outperformed non-native speakers only in certain conditions, and the role of short periods of rest remains unclear. The findings of this research provide insights into how various factors play a part in novel word learning.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716424000031

Replication package

Replication data and materials for this article can be found at https://osf.io/dt2sk/.

Funding statement

This work was funded by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada Partnership Grant (Words in the World, 895-2016-1008).

Competing interests

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.