Introduction

The history of almost every field of cultural production chronicles the struggle between innovators operating at margins of a field—alias outsiders—who challenge the existing order and seek to establish their leadership by deploying and accumulating different forms of capital, and powerful field insiders interested in holding onto the status quo. Yet as cultural fields tend to reproduce the power and privilege structure of incumbent groups, outsiders’ chances of involving themselves meaningfully in the production of culture and proving their worth are typically slim.Footnote 1 Consider this passage from Edward Said’s penetrating reflections on the structure of modern society, wherein he evokes the kind of challenge outsiders must face as they seek to advance a new vision or an alternative way of doing things: “I have had in mind how powerless one often feels in the face of an overwhelmingly powerful network of social authorities […] who crowd out the possibilities for achieving any change.”Footnote 2 This observation underscores a fascinating puzzle: when it comes to establishing legitimacy, the odds are against outsiders because, by definition, outsiders are foreign to the field they seek to enter, are usually disengaged from the centers of power, lack crucial credibility markers, and have only few if no ties to field insiders. However, “outsiderness” also provides actors with a unique vision and distinctive approach to problems.Footnote 3 What are the processes that allow outsiders to stake out some ground in the insiders’ terrain, especially when their ideas clash with the status quo?

We address this question through a theoretically informed historical study of Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel’s entrepreneurial journey as a fashion designer from her early years as a “social outcast from the provinces”Footnote 4 to her rise to success and consecration as an icon within the haute couture field. Chanel’s case offers unique historical material for examining the trajectory of one of the first female entrepreneurs in business history to achieve a truly global success that still lasts, with the further challenge of establishing herself in what at the time was a male-dominated, mature, and stable field.Footnote 5 Described by George Bernard Shaw as one of the two most influential women of the twentieth century—the other was Marie Curie—Chanel was raised in an orphanage in a remote village in central France. Lacking a formal education and entering Parisian society as a mistress, she revolutionized the fashion industry by pioneering sportswear design and the use of textiles never seen before in haute couture dressmaking. Chanel’s innovation was not simply to remove the corset from the silhouette; she completely transformed the female silhouette: she shortened dresses, revealed ankles, freed the waistline, cut women’s hair, and bronzed their skin.Footnote 6 She also imposed the color black in haute couture, which was used only for bereavement, and made it an elegant color that women could wear at any time.

Despite modest cultural capital and entirely devoid of social, economic, and symbolic capital, Chanel managed to leave an unparalleled mark in the development of the fashion industry. Starting as a hat maker in 1909, she had already built a lucrative fashion business by 1916, with three successful stores and a staff of three hundred employees. In 1931 she employed twenty-four hundred women in her twenty-six sewing ateliers, and her business grossed 120 million francs that year (approximately $70 million today), the highest of any couturier in Paris;Footnote 7 her business nearly doubled in 1935 when, in addition to running a fashion house, she also owned various boutiques, a textile business, a costume jewelry workshop, and several brand extensions (including the successful perfume Chanel No. 5) and managed more than four thousand employees producing twenty-eight thousand items per year.Footnote 8 The fortune she amassed was enormous, especially for a woman at that time. In October 2020, the Palais Galliera, the City of Paris Fashion Museum, opened the first retrospective exhibition—Gabrielle Chanel. Fashion Manifesto—to honor the designer who brought fashion into the twentieth century by changing women’s style and appearance permanently. The exhibition examined Chanel’s unique influence on fashion history.Footnote 9 Few fashion designers could lay claim to comparable cultural significance.Footnote 10

We are not the first to analyze Coco Chanel’s career and accomplishments. Her life and impact on the fashion industry has been the subject of wide academic interest. Her biography has been thoroughly documented.Footnote 11 There is likewise abundant literature on Chanel’s stylistic and material innovations,Footnote 12 cultural influence,Footnote 12 and role within the modernist movement.Footnote 14 A lesser-studied topic, however, is Chanel’s entrepreneurial trajectory in light of, but also in spite of, her unique initial socio-structural position.Footnote 15 One theoretical perspective that we find particularly useful in thinking of Chanel’s puzzling journey form the margins to the core of the global haute couture industry is the sociology of ideas, a perspective associated especially with the work of theorists like Pierre Bourdieu and others in the same tradition (e.g., Charles Camic, Neil Gross, Neil McLaughlin).Footnote 16 Scholars in this tradition focus on individuals and groups who specialize in the production of cognitive, expressive, and evaluative ideas and examine the processes by which those ideas emerge and are pushed into good currency. These actors are seen as involved in historically situated legitimacy struggles that are always structured by the social properties of the fields in which these struggles occur. On the one hand, incumbent groups work to defend and reproduce their power structure and impose consensus; on the other, challengers try to call into question the dominant groups.Footnote 17 Audiences (critics, users, etc.), who occupy an intermediate position between individual actors and a field, are central to this oppositional struggle, because they control and therefore regulate access to the resources that challengers need to further their ideas.

Building on Bourdieu’s work on forms of capital—in particular, his distinction between cultural, economic, social, and symbolic capital—we argue that the interaction with these audiences is critical to understand how challengers engage in various forms of capital deployment and conversion to establish their leadership in a field. The success of any strategy, particularly strategies that aim to subvert the status quo, depends on having the right quantities of each type of capital as well as mastering the processes of capital conversion and accumulation.Footnote 18 As we shall see, at the heart of Chanel’s entrepreneurial journey was her ability to stimulate an upward spiral of capital accumulationFootnote 19 by cultivating connections to other like-minded artists, sympathetic sponsors, and influential members of Parisian high society.

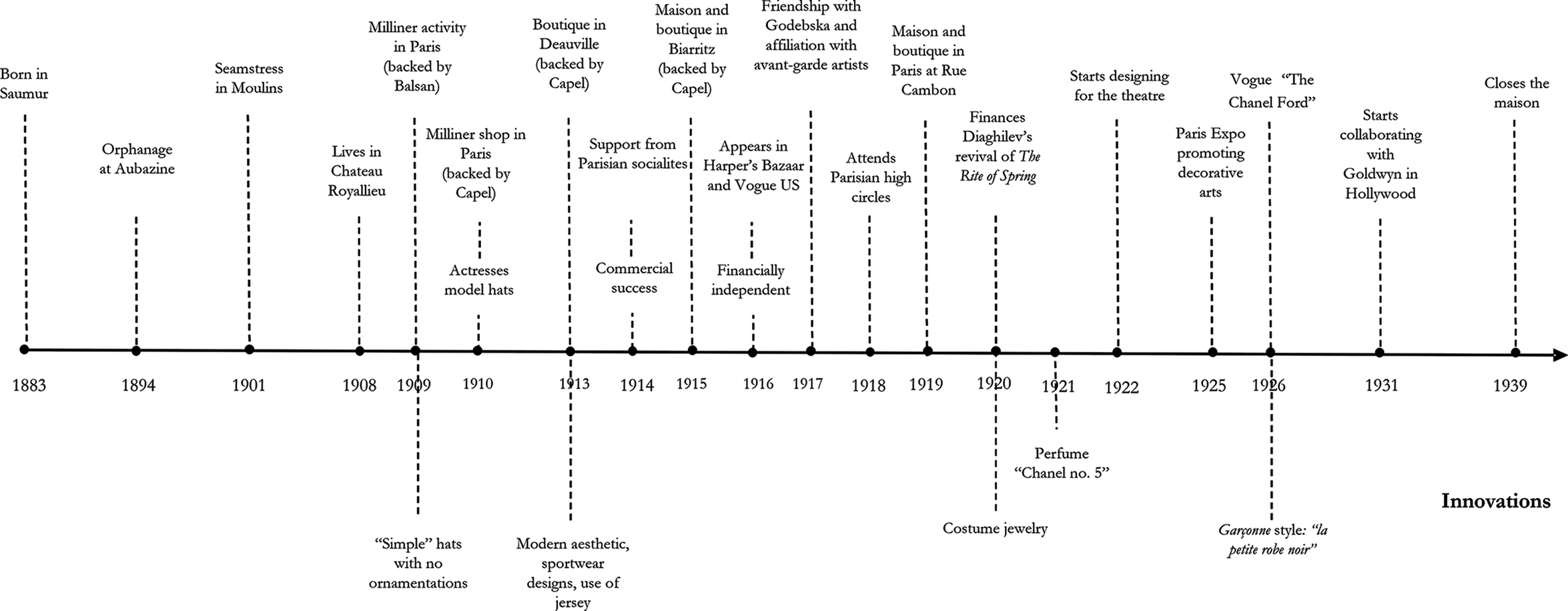

We start by outlining a theoretical agenda that identifies salient social forces informing the outsider problem. Next, we develop an historical narrative encompassing four main phases in Chanel’s entrepreneurial journey. The phases develop as follows: the field of Parisian haute couture (mid-nineteenth century till 1908, when Chanel started to design her own hats); the entry of Chanel into the fashion field (1909–1912); her early capital accumulation (1913–1919); the diffusion of Chanel’s modern fashion following World War I (1918–1925); and the transition of Chanel to the core of the fashion field and her consecration (1926–1939). We conclude the historical narrative by briefly discussing her last years of activity, from her voluntary retirement in 1939 to her comeback in 1954 to her death. We then extrapolate key insights from this historical narrative to elaborate a multilevel perspective that exposes how the interplay between agentic efforts, social audience dynamics, and large-scale transformation created a favorable social space for Chanel’s modern fashion, allowing for an increasing accumulation and mobilization of nonstandard forms of capital.

Methodologically, we accomplish this by adopting a sociohistorical approach to reach “a theorized understanding of the historical particularities and contingencies of the series and relationships under analysis,”Footnote 20 an approach called “history in theory.”Footnote 21 Central to this understanding is the recognition that agency and structure must be treated dialectically. As Ritzer put it: “A dynamic and historical orientation to the study of levels of the social world can be seen as integral parts of a more general dialectical approach.”Footnote 22 This dialectical approach illuminates the process by which, over time, a highly resource-constrained outsider may rise to prominence and highlights the shifting influence of forces operating at different levels (micro, meso, and macro) in the dynamics of capital accumulation, deployment, and conversion. In developing a process view of the career trajectory of one of the first women with global entrepreneurial impact in business history, this paper also responds to recent calls by female entrepreneurship scholars for “more process-oriented research within work on female entrepreneurship.”Footnote 23

Conceptual Background

Our overall theoretical argument is based on three observations. First, novelty claims that threaten the status quo often originate from actors who are marginal to a particular field, that is, actors “who are not initially engaged in the occupation which is affected by them and are, therefore, not bound by professional custom.”Footnote 24 Less constrained by prevailing norms and standards “outsiders, fringe players, and excluded voices bring ideas into established institutions, cultures and paradigms that are unlikely to be created by individuals more socially embedded in established ways of thinking.”Footnote 25 However, lacking the authority of insiders—and their privileged access to social, cultural, symbolic, and economic capital—such actors face significant obstacles in building legitimacy. Second, cultural fields usually include multiple audiences whose members may use different criteria to assess the desirability and the direction of change implicit in outsiders’ novelty claims. Crucially, outsiders’ chances of reaching legitimacy hinge on their ability to appeal to homologous social audiences,Footnote 26 especially those that control and hence can provide access to the material and symbolic resources they need to credibly voice their ideas. Third, while cultural fields tend to resist the entry of outsiders, this resistance may not be strong enough to prevent convulsive moments following exogenous shocks or other large-scale transformative events that suddenly alter existing relations in a field and prompt a shift in taste. By subverting a field’s structure, transient large-scale perturbations can precipitate outsiders’ entry into a field and make it more permeable to new offers. These three observations reflect the role of forces that operate at different levels of analysis, which we discuss in the following sections before introducing our historical and narrative methods.

Insiders, Outsiders, and Capital Accumulation

Field theorists agree in conceptualizing fields of cultural production as configurations of relations between positions that operate to help reproduce the privilege and power structure of dominating groups and define the positions of dominated groups. Both groups participate in a struggle in which they attempt to usurp, exclude, and establish control over the mechanisms of field reproduction and the type of power effective in it.Footnote 27 The structural outcomes of this struggle are usually theorized as dichotomies that classify actors into incumbents and challengers, old-timers and newcomers, insiders and outsiders. Indeed, in every field, the dominant groups “have an interest in continuity, identity and reproduction, whereas the dominated, the newcomers, are for discontinuity, rupture and subversion.”Footnote 28 Bourdieu argues that the precise social position of individuals in these competitive arenas is dictated by the amount and types of capital available to them—economic, cultural, social, and symbolic. For Bourdieu, capitals are unevenly distributed relational assets that endow actors with field-circumscribed agency and deployed to achieve and reinforce social distinction.Footnote 29 Economic capital, the control of financial resources, is a major source of power and a key driver of stratification, because wealth can be readily converted into other forms of capital. Social capital comprises relationships and networks between actors that provide recognition and the benefits of shared group resources.Footnote 30 Cultural capital includes dispositions, skills, and knowledge that can be acquired through education, informal transmission, and socialization. Finally, symbolic capital denotes distinctions such as accumulated prestige, reputation, honor, and fame. In the struggle to improve their positions, actors can exchange or transmute one form of capital into another, that is, convert one form of capital into another.Footnote 31 This is particularly important for those actors who aim to challenge the positions of dominant actors and actively create new positions in a field through the pursuit of strategies that exploit “newly emerging possibilities stemming from developments in tastes, incomes and technologies, moving quickly before more dominant players can nullify their strategic moves.”Footnote 32

As institutions that perpetuate cultural inheritance such as family and school significantly shape access to different forms of capital, extant structures of elite dominance and social distinction self-reproduce, thus minimizing opportunities for non-elite field members to supplant insider actors and advance new offers.Footnote 33 As a result, the propensity to produce work that departs from prevailing expectations is not randomly distributed but tends to map onto a field’s social structure: insiders are more likely to defend orthodoxy in cultural production.Footnote 34 In contrast, outsiders are more likely to make offers that depart from a field’s prevailing expectations, because “people on the periphery of a field, and thus less beholden to its practices, are more likely to initiate change.”Footnote 35 Yet the barriers to capital accumulation erected by insiders are so daunting that “many opportunities for successful challenge die before they produce change,”Footnote 36 especially when the initial settlement defining a field proves effective in creating an arena that is advantageous for those who have fashioned it.Footnote 37 The paradox for the outsiders is precisely that the very social position that allows them to advance dissenting ideas that challenge the prevailing order also implies that they lack crucial markers of credibility to attest to the legitimacy of such ideas. Typically, outsiders lack economic capital, have no or limited social ties to insiders, and no power or status in the fields they seek to challenge; in particular, they have neither the authority nor trust of experts. So, under what conditions can outsiders break through hierarchical social structures based on capital accumulation and successfully further their alternative views?

Bourdieu identifies two crucial conditions. The first hinges on the availability of a homologous reception space, namely an audience whose members are predisposed by their view of the social world, beliefs, and taste to accept (or at least listen to) the types of ideas proposed to them. The second rests on the occurrence of exogenous changes that open up space for dissident positions. Bourdieu suggests that because outsiders’ dispositions and position takings are often in conflict with the doxa (taken for granted sense of reality), they are unlikely to succeed without help from external changes. These changes “may be political breaks, such as revolutionary crises, which change the power relations within the field … or deep-seated changes in the audience of consumers who, because of their affinity with the new producers, ensure the success of their products.”Footnote 38 We now turn to these two social forces and elaborate on their role in shaping outsiders’ legitimacy struggles.

Connecting to Homologous Audiences

The appreciation of legitimacy as “a relationship with an audience”Footnote 39 rather than a possession of the actor is of particular relevance to the understanding of field dynamics, and we take seriously Bourdieu’s suggestion that “all the homologies which guarantee a receptive audience and sympathetic critics for producers who have found their place in the structure work in the opposite way for those who have strayed from their natural site.”Footnote 40 In Bourdieu’s assessment, the existence of a homologous audience—that is a receptive social space whose members share with the outsider the same or similar dispositions and thus are more eager to accept and support his or her ideas—is a crucial precondition for enabling outsiders to access the capital they need to pursue their ideas and make an impact on the inside. Deviant offers that clash with the dominant view “cannot be understood sociologically unless one takes account of the homology between the dominated position of the producers […] and the position in social space of those agents […] who can divert their accumulated cultural capital so as to offer to the dominated the means of objectively constituting their view of the world.”Footnote 41 The challenge for the challenger is to find a homologous audience—one whose view of the social world, beliefs, and tastes is attuned to theirs.Footnote 42

Empirical accounts consistent with this view include Sgourev’s analysis of the rise of Cubism, in which it is shown that the fragmentation of the twentieth-century Parisian art market resulted in an increasing taste for experimentation among relevant social audiences more attuned to Cubism’s radical novelty, which was emerging at the margins of the French art world.Footnote 43 This suggests “that disconnected actors may be successful in innovation not because of the specific actions that they undertake but because of the favourable interpretation of these actions by members of the audience.”Footnote 44 Farrell’s (Reference Farrell2008) research on collaborative circles too is illustrative of how like-minded actors can form a homologous social space where challengers are more likely to find the material, emotional, and symbolic capital they need.Footnote 45 Within this space, each member is provided with “the backing of the collectively owned capital,”Footnote 46 that is, the convertibility of this capital avails outsiders with resources otherwise very difficult to access. Similarly, Cattani et al. demonstrated that audiences of critics are more likely to allocate their symbolic capital to peripheral members of the Hollywood field than to central players.Footnote 47 Thus, by leveraging their relationship with these groups, outsiders can strengthen their assault on the basis of homologies between positions.

These arguments and findings suggest that shifting the focus on the demand-side role of social audiences in shaping legitimacy struggles opens up the possibility of theorizing on meso-level dynamics shaping fields’ variable disposition toward outsiders’ claims, irrespective of the amount of resources supporting them. They also suggest that the way audiences respond to novel offers may vary—sometimes dramatically—depending on their particular dispositions.Footnote 48 That brings us back to Bourdieu’s earlier reminder about the importance of considering macro-level sources of change.

Exogenous Shocks and Field Destabilization

Although a field’s institutional arrangements tend to resist outsiders’ challenges, such resistance may not be strong enough to forestall convulsive moments following exogenous shocks or other dramatic events that suddenly alter the status quo, setting in motion “a period of crisis in which actors struggle to reconstitute all aspects of social life.”Footnote 49 These events can take multiple forms, including revolutions,Footnote 50 wars,Footnote 51 terrorist attacks,Footnote 52 or natural disasters.Footnote 53 Alan Meyer used the term environmental jolts to describe events far from equilibrium, which he defined as “transient perturbations,” difficult to foresee and having a disruptive impact on organizations.Footnote 54

Capitalizing on this intuition, scholars have noted that similar events can catalyze the mobilization of outsiders who can advance their positions in a field’s social structure, precipitate the entry of new actors, or facilitate the rise of existing actors.Footnote 55 While most challenges from the periphery of a field do not produce dramatic changes, the occurrence of exogenous shocks may facilitate the emergence of “new logics of action,”Footnote 56 pushing a field toward more favorable settlements for new entrants and alternative practices and overthrowing core actors. Randall Collins, for example, illustrates how the political events leading up to the French Revolution were crucial in creating the intellectual opportunities necessary to unleash the creativity that spawned German Idealist philosophy: “These political and military upheavals […] cracked the imposed religious orthodoxy, and allowed a variety of new philosophical statements on religious topics.”Footnote 57 Likewise, Wesley Sine and Robert David document how the wave of entrepreneurial agency that hit the U.S. electric power industry in the aftermath of the oil crisis caused “increasing access for peripheral actors to central policy makers.”Footnote 58 Focusing on external shocks complements the previous audience-based perspective by highlighting the role of shocks in changing a field’s attention space and sensitizing social audiences to alternative ideas, cultural practices, or perspectives, but also helping challengers form new strategic connections that they can mobilize to access the capital they need.Footnote 59

The above research streams expose social dynamics operating at multiple levels of analysis that jointly shape the process through which a marginal actor can break through the hierarchal social structures of a mature and stable field. Each of these lines of scholarship, however, also confronts the limitations arising from its specific theoretical concerns.Footnote 60 Structural position-based arguments emphasize outsiders’ superior motivation and propensity to advance offers that deviate from a field’s normative expectations, but fall short of articulating the circumstances that precipitate the same actors to do so. Research emphasizing macro-level exogenous shocks, on the other hand, sheds light on the conditions that precipitate outsiders’ entry into a field but fall short of accounting for the micro-level processes by which outsiders go about accumulating and deploying different forms of capital. Meso-level accounts have greatly contributed to bridging the gap between micro and macro explanations by showing that the consequences of a given innovation effort are not intrinsic in the act, but rather will depend on the receptiveness of the social world within which such an effort takes place.Footnote 61 Yet we still have limited understanding of why and under what conditions this receptiveness can change over time, sometimes resulting in dramatic twists and turns in the journey from the margins to the core of a cultural field.

The largely autonomous pursuit of these lines of inquiry at the same time has discouraged investigation into questions concerning the interdependent relations between the micro-, meso-, and macro-levels of analysis in sustaining or hindering an outsider’s innovation efforts. To explore these relations, we turn now to a historiographic analysis of Chanel’s entry into the field of fashion. Based on this historical material, we elaborate a multilevel account of Chanel’s entrepreneurial journey that sheds light on the capital conversion dynamics that enabled her to emerge as a dominant economic actor and to be elevated to an iconic figure in the haute couture field. We argue that without adopting a multilevel perspective, it would not be possible to properly understand this journey.

Data and Methods

We use Chanel’s case material to develop a strategic narrative, that is, an account of actors and events based on a subset of historical facts that allow us to systematize the existing knowledge in a way that promotes theoretical advancement.Footnote 62 To ensure the robustness of such a historically grounded account, we relied on Matthias Kipping, R. Daniel Wadhwani, and Marcelo Bucheli’s methodology, which requires that the historical sources be triangulated to reduce bias and increase confidence in the empirical results.Footnote 63 To this end, we carefully analyzed historical facts that were first ordered chronologically, then concatenated to unveil sequential chains, and finally arranged in a strategic narrative.Footnote 64 Our historical analysis draws from several sources that describe the history of fashion from the end of the nineteenth century to the first decades of the twentieth century, including Chanel’s contribution to fashion. Available sources are historical, sociological, or biographical. Indeed, Chanel’s personal life and career have been copiously documented in past works, including memoirs by her friend the poet Paul Morand and The World of Coco Chanel by her biographer and former Vogue editor Edmonde Charles-Roux.Footnote 65 Table 1 summarizes the data sources used for the analysis.

Table 1. Data sources

Consistent with historically oriented research, the primary concern of the present study is not to advance explanations that can be generalized to other settings. Our narrative is intended to sharpen, illustrate, and ground our theoretical agenda instead of providing an empirical test.Footnote 66 It thus exposes key contextual circumstances that affect the opportunities facing outsiders and the constraints to their efforts. This history- and field-sensitive account helps to unveil the reasons why the same innovative efforts may be opposed at one time, but praised and seen as legitimate at another, or vice versa.

The Field of Parisian Haute Couture: A New Fashion in the “Old” Era

To appreciate the origins of the fashion revolution at the outset of the twentieth century and the scope of Coco Chanel’s contribution, it is important to start with a description of the field of haute couture around this period. As the French fashion writer René Bizet once put it, “Every revolution begins with a change of clothes.”Footnote 67 Indeed, the years just before the outbreak of World War I had witnessed “the beginning of modern fashion.”Footnote 68 During those years, women progressively abandoned the so-called S-corseted silhouette, overly elaborate and long skirts, and pastel shades in favor of simple and straight silhouettes, softer and more flexible materials, and natural colors. The war strongly accelerated this process, but the corset had already begun to evolve into a softer and more comfortable garment by 1913, partly in line with the modernist movement.

This process was the culmination of an effort to reform women’s clothing that started in the second half of the nineteenth century. Several dress reform movements—inspired by concerns about politics, health, hygiene, and aesthetics—had emerged in America, England, and continental Europe. Dress reformers promoted “rational alternatives” such as “bifurcated” garments, split skirts, or knickerbockers that were considered highly controversial and usually triggered a negative response.Footnote 69 An important advocate of this movement was the American activist and editor Amelia Bloomer who, in 1851, introduced the so-called “Bloomer costume.”Footnote 70 Yet this reform movement did not produce a radical change, because only the feminists adopted the new dress. Efforts to reform clothing were also made in Great Britain, where the pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic movements developed the “artistic dress”— a garment that flowed and draped elegantly on the body.Footnote 71 The work of architect Henry van de Velde, a proponent of dress rationalization, contributed significantly to the debate on dress reform in Germany.Footnote 72 To make the rational dress more attractive to women’s tastes, he tried to shift attention from the medical sphere to a purely aesthetic realm. At the same time, in Vienna, a group of architects, designers, and artists (e.g., Gustav Klimt, Josef Hoffmann, and Koloman Moser) initiated a movement that sought new forms of aesthetic expression that reflected changes in modern life. In 1911, the establishment of the Wiener Werkstätte fashion division marked this transformation.Footnote 73 The impact of these early attempts to modernize female clothing, however, was limited to feminist and artistic circles, remaining rather confined compared with the change that took place in Paris. Thus, at the beginning of the twentieth century, when Chanel started making clothes, fashion was still lagging behind societal and cultural changes.

During the period called mode de cent ans, which began around the mid-nineteenth century and lasted until the mid-twentieth century, Paris “dictated the women’s fashion, which was followed internationally.”Footnote 74 Paris was the epicenter of the arts at the time, and female high fashion (i.e., haute couture) represented the leading production model of the Parisian fashion business.Footnote 75 The first haute couture house in Paris was established by the English couturier Charles Frederick Worth in 1858, and the term “fashion designer” was coined to designate an artist, not a mere dressmaker. French pioneer designers founded and institutionalized early couture houses whose basic features would characterize the system of fashion production for a whole century.Footnote 76 As it is usually the case in mature fields, the Parisian fashion world exhibited a distinct status ordering wherein a few couturiers operating at the top had all the incentives to maintain the prevailing arrangements. The identity of couture houses was defined by traditional practices that set the boundaries of the industry and the rules of the game. The existence of protective institutions and rules emphasizing stability and conformity prevented attempts to rejuvenate the field.

The oldest and most important institution for the development and maturation of the sector was the union of employers in the high fashion sector. In 1868, Le Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne was founded for the first time as a safeguard for high fashion.Footnote 77 In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the high fashion industry grew rapidly, gaining importance in the French economy: despite strong local roots, Parisian fashion had increased its international impact by contributing significantly to French exports. The Chambre Syndicale established rigid industry regulations to protect its prestige: not all of the haute couture houses could join the institution, and only producers of very high quality garments were accepted as members. According to Véronique Pouillard,Footnote 78 the Chambre Syndicale acted as a field gatekeeper by raising the membership bar so high that only a small elite group of couturiers became members before haute couture earned a legal definition in 1943.Footnote 79 Thus, the Chambre Syndicale greatly contributed to the stability of the field with the development of rigid norms. In the mythology of Paris fashion, and especially so in the case of haute couture, there was a clear divide between the Parisians and the “barbarians or provincials,”Footnote 80 as “provincials put on clothes, the Parisienne dresses.”Footnote 81 Hence, following Worth in 1858, influential and dominant designers established their fashion houses in the French capital: Jacques Doucet in 1870, Gustave Beer in 1877, John Redfern in 1886, Jeanne Lanvin in 1886, Jeanne Paquin in 1893, the Callot sisters in 1896, Louise Chéruit in 1901, and Paul Poiret in 1903.Footnote 82

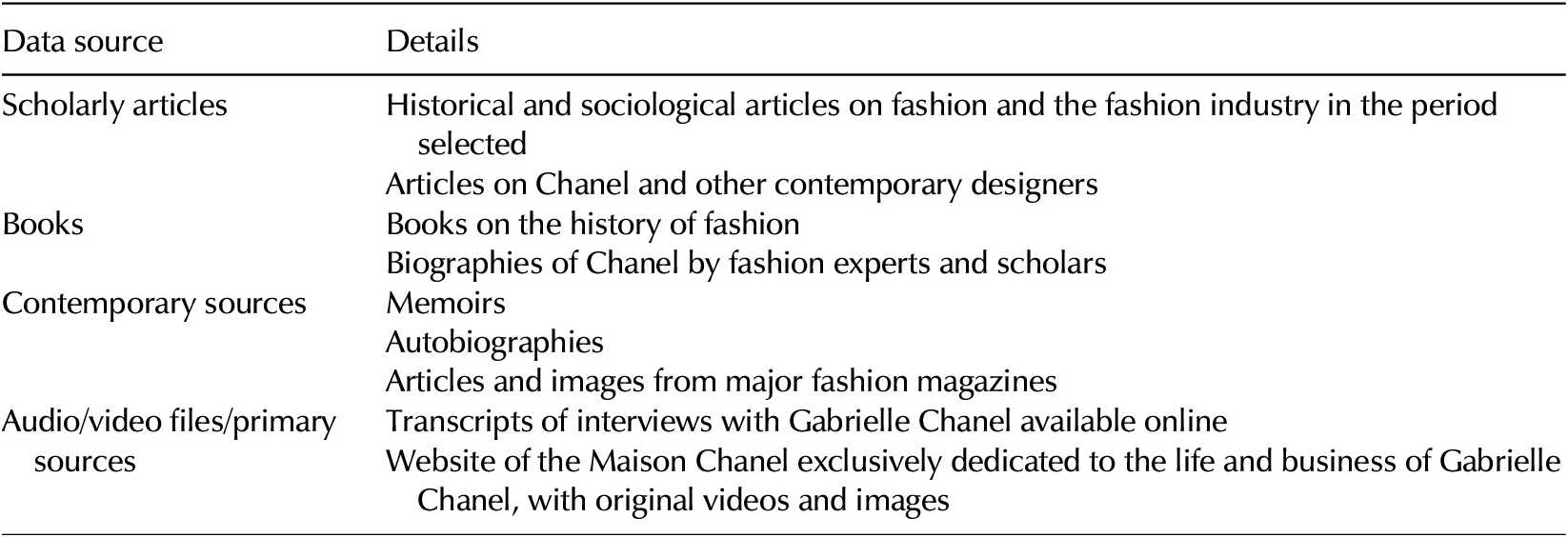

The highly institutionalized field of haute couture and, in general, Parisian society were like a stage on which fashion was displayed according to specific “rules [that were] maintained, preventing fashion anarchy.”Footnote 83 Strict rules determined the appropriate dress to wear at the theater or the racetrack—which at the time were regarded as social events, or rituals, in which fashion was part of the public spectacle.Footnote 84 Haute couture, in particular, had rigid cultural norms that created strong conformity to social pressure among both producers and consumers. The dominant style, the so-called belle époque fashion, consisted of cumbersome outfits, heavy fabrics, lots of ornamentation, and a clearly defined silhouette: use of a corset (the S-bend corset was fashionable during the early 1900s) and long skirts with a cage crinoline (a structured petticoat designed to hold out a woman’s skirt) or with skirts fitted over the hip and fluted toward the hem. Dresses were supposed to signal the wealth and status (i.e., social position) of women’s husbands or families;Footnote 85 and while the upper class adopted a taste for outdoor activities from Great Britain, women participated in them wearing inappropriate clothing: long and bulky skirts, fragile hats, and narrow shoes with high heels (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Belle époque fashion: (A) dinner dress by Jacques Doucet, 1909;

(B) women attending races at Auteuil, 1913 (photo by Séeberger Frères); (C) ensemble by House of Worth, ca. 1900.

Source: (A) Rennolds-Milbank, Couture, 41; (B) https://www.moma.org/collection/works/89088; (C) https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/107017.

Until Chanel—and, in general, during the first decade of the twentieth century—fashion aimed to accentuate women’s physical charm, sometimes to the point of caricature, as several layers of lacing compressed a lady’s chest underneath the corset. As a result, women could not walk without the assistance of a man: “with wives unable to put one foot in front of the other unaided, the open-air craze could not but enhance the authority of men.”Footnote 86 Referring to that period, Chanel said that “1914 was still 1900 and 1900 was still the Second Empire, […] for it lacked a way for expressing itself honestly.”Footnote 87 The radical ideas that transformed women’s fashion in the 1920s had started to emerge years before when, in 1909, Chanel first introduced her personal style with a straight and simplified silhouette and casual clothing inspired by upper-class male sportswear. To understand the origins of this transformation, it is important to examine the early years of Chanel’s entrepreneurial journey, particularly the context in which she was born, raised, and accumulated her cultural capital, to which we now turn.

An Outsider Entering Modern Fashion

Gabrielle Bonheur Chanel was born in 1883 in Saumur, a small rural town, where she was raised in conditions of extreme poverty.Footnote 88 Her father worked as a traveling peddler and her mother was a laundress.Footnote 89 When she turned twelve, her mother died and her father abandoned his five children. Chanel and her two sisters were sent away to an orphanage at the abbey of Aubazine, where she spent nearly seven years. After the orphanage, Chanel entered the Notre Dame Pensionnat, an institution for poor girls in Moulins—where she was accepted to finish school as a charity case, doing housework to pay for her schooling and housing. At the orphanage, Chanel received a rudimentary education, but she learned how to sew, and this helped her find employment as a seamstress in Moulins in a lingerie and hosiery shop. She also sang in cabarets frequented by cavalry officers in Vichy and Moulins. It was at this time that Chanel took on the name “Coco”—possibly based on two popular songs she used to perform.Footnote 90 Because of the poor quality of her voice, however, her career as café singer was short-lived.

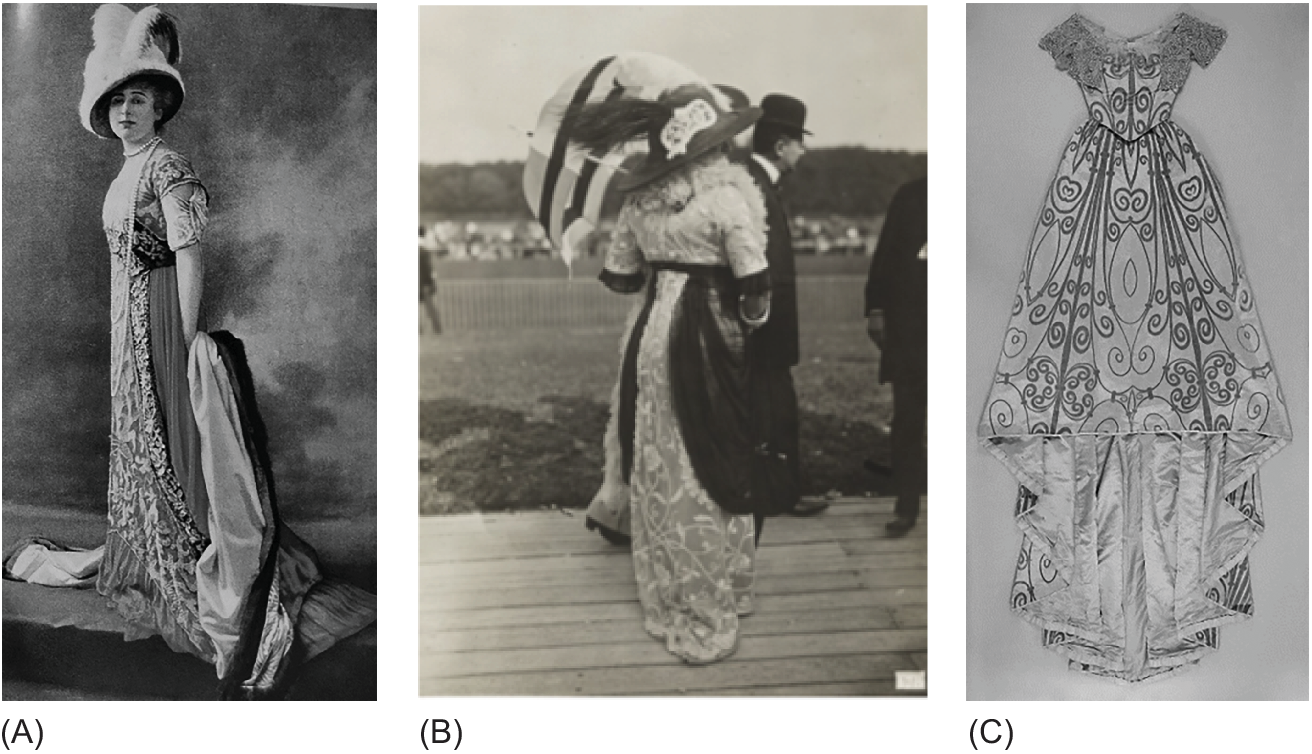

At Moulins, Chanel met Étienne Balsan, a young ex–cavalry officer and wealthy textile heir. In 1908, they moved together to his Chateau de Royallieu where, given Balsan’s interest in breeding horses and participating in races, she became acquainted with the world of horses and racetracks. Here Chanel was introduced to sport, rules, and discipline—concepts that would influence her first designs. In 1909, with Balsan’s financial support, Chanel started as a milliner in Paris selling hats—which she was already making for herself and her friends in Balsan’s garçonniere in boulevard Malesherbes. In Balsan’s circle of friends Chanel also met Arthur “Boy” Capel, a British man of distinction and a famous polo player, who also became her lover. In 1910, with Capel’s funding, Chanel opened her first shop at 21 rue Cambon in Paris, making hats under the name “Chanel modes.”Footnote 91 She then devoted herself to changing the rest of the women’s attire by introducing casual clothes. Her style departed immediately from that of her contemporaries and embodied the idea that being fit mattered more than wearing a corsetFootnote 92—and “this was radical, her idea of the body.”Footnote 93 As Chanel put it: “Eccentricity was dying out; I hope what’s more, that I helped kill it off.”Footnote 94 Chanel also stood for prewar experimentation with masculine style and fabrics, eventually disrupting the way fashion’s style and practices mapped onto those of gender and class distinctions.Footnote 95 Figure 2 illustrates the stark contrast between Poiret’s and Chanel’s ideas on women trousers: while the former turned to exoticism and decoration for his “harem” pants outfit, Chanel borrowed the design of her trousers from sailors.

Figure 2. (A) Robes sultanes or “harem pants” by Paul Poiret, 1911.

(B) Gabrielle Chanel wearing sailor shirt and trousers, 1930. © All rights reserved

Source: (A) Morini, Storia della moda, 198; (B) https://www.chanel.com/us/about-chanel/the-founder.

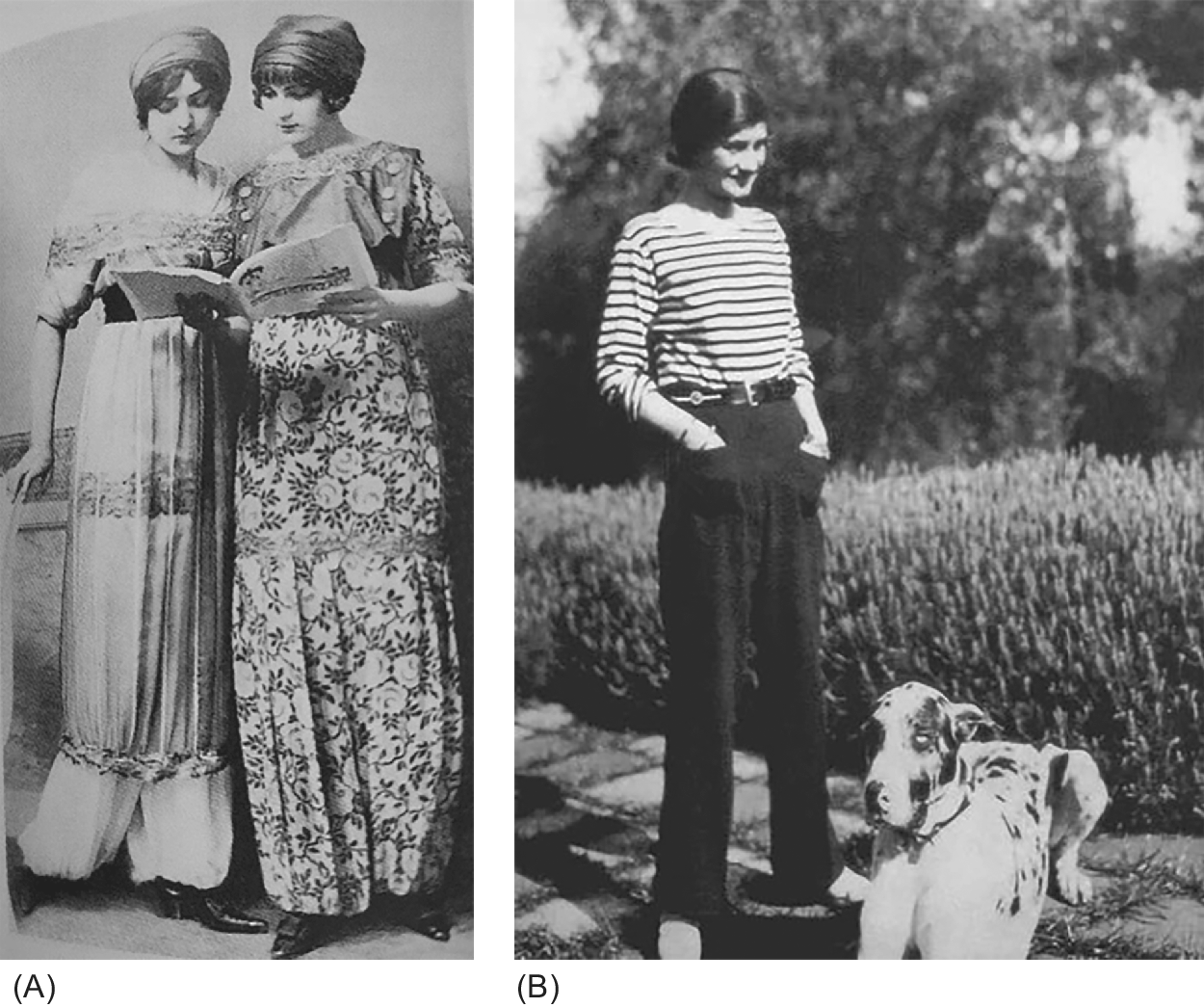

Chanel’s unique socio-structural location played a crucial role in shaping her vision. The years she spent at the orphanage—where the initial accumulation of her cultural capital mainly took place—had a lasting effect on Chanel’s habitus, that is, the deeply ingrained dispositions that guide behavior and thinking.Footnote 96 According to Bourdieu, “habitus” refers to the way the social environment to which people are exposed becomes deposited “in the form of lasting dispositions, or trained capacities and structured propensities to think, feel and act in determinant ways, which then guide them in their creative responses to the constraints and solicitations of their extant milieu.”Footnote 97 For instance, the Romanesque purity and austerity of the Aubazine Abbey—the ascetic place where she was raised—would inspire her sense of rigor and simplicity, as well as her taste for black and white: white corridors and white walls contrasted with black painted doors and black aprons worn by the nuns. Black and white were also the colors of the dresses she wore during her childhood: white blouses and black skirts were the uniforms worn by orphans.Footnote 98 Chanel admitted that “it was my Auvergne ‘aunts’Footnote 99 who imposed their modesty on the beautiful Parisian ladies. Years have gone by, and it is only now that I realize that the austerity of dark shades, […] the almost monastic cut of my summer alpaca wear and my winter tweed suits, all that puritanism that elegant ladies go crazy for, came from Mont-Dore. […] I was a Quaker woman who was conquering Paris.”Footnote 100 Figure 3 highlights Chanel’s hallmarks: the black and white, a little boater worn down over the ears, the austerity and simplicity of her garments, and the use of jewelry.

Figure 3. Portrait of Chanel wearing a little black dress, a typical hat, her Maltese cross cuffs, and her iconic necklace with strands of faux pearls with interlocking CC charms. © Man Ray Trust/ADAGP Paris 2016.

Simplicity and austerity became indelible features of Chanel’s style. Remembering the years spent at Chateau de Royallieu attending horse races, Chanel said: “It is not that I love horses. […] It is nevertheless true that horses have influenced the course of my life.”Footnote 101 While watching racetracks, Chanel noted that women attended these sporting events wearing encumbering outfits and enormous hats, with complicated decorations made of feather, fruits, flowers and ribbons, “but worst of all, which appalled me [Chanel], their hats did not fit on their heads.”Footnote 102 Chanel, on the other hand, had a more practical style: she made herself a trim little boater suited for the open-air conditions, secured with a huge pin against the stormy winds of the mistral, and wore a man’s white collar with a necktie, already a Chanel trademark in 1907. Twenty years later, women all over the world would wear this ensemble.Footnote 103

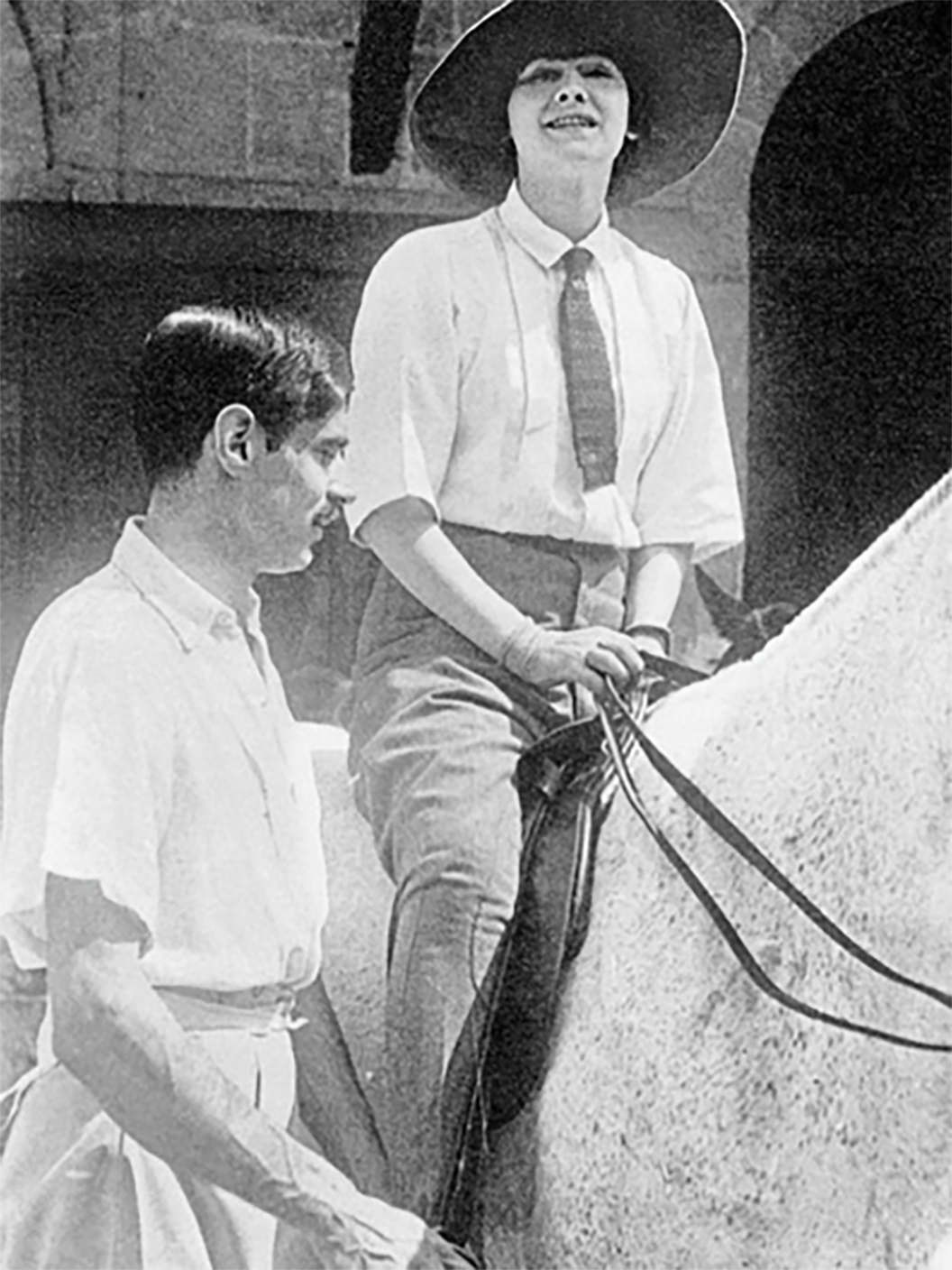

Chanel’s attitude was well suited to chateau life. As Figure 4 shows, in 1908 Chanel was already sporting a masculine white collar, necktie, shirt, and pants—practical garments for horse riding. In the world of stables and horses at the chateau, Chanel discovered the core principle of her style: elements of male attire adapted for feminine use. Her designs borrowed elements of upper-class men’s sportswear, particularly from the attire of her lovers—first Étienne Balsan and then Boy Capel. As fashion critics noted, “The Chanel style has everything to do with elegance but is founded on elements once considered foreign to it: comfort, ease and practicality.”Footnote 104 Chanel stated that the most difficult aspect of her job was “to allow women to move with ease, to allow them not to feel dressed up […] Very difficult! […] and this is the gift I think I have.”Footnote 105

Figure 4. Arthur “Boy” Capel with Chanel on horseback, 1908, at Chateau de Royallieu.

Source: Vaughan, Sleeping with the Enemy, 7.

In the years she spent at the margins of society, Chanel also developed an aesthetic disposition characterized by the primacy of function over form, epitomized by her idea of clothes as uniforms. It takes an appropriate dress to achieve a distinctive social identity like the uniform she wore at the orphanage: miserable but conferring a precise role in society.Footnote 106 Other “uniforms” that influenced Chanel were those used for horse riding and designed to facilitate movement. The dresses worn by irrégulières (i.e., mistresses) reflected a luxurious and excessive style. An irrégulière herself, Chanel rejected such female eccentricity, opting instead for a more masculine and sporty style. Her goal was to defy the dominant overly feminine fashion canon, because “she had to set herself apart from everyone else in her position.”Footnote 107 As Salvador Dalí remarked: “Chanel always dressed like the strong independent male she had dreamed of being.”Footnote 108 In fact, her designs could not appear more feminine, yet they were “based in large part on a masculine model of power and freedom.”Footnote 109 Chanel’s “little black dress” of the 1920s also was inspired by the social worlds she inhabited during her troubled upbringing. The dress reflected Chanel’s resentment against parade clothes representative of the French society’s established order but also her desire to provide women with the same power of men: the stiff white collar and cuffs make a chic statement of masculine conformity and superiority; but it also recalled the nuns, in their black dresses and white coifs.Footnote 110 Interestingly, adding a white collar and cuffs to a simple black dress “perversely” transformed an aristocrat into a servant. This strongly unconventional, simple, and practical style marked the beginning of “an elegance in reverse […] the stable would dethrone the paddock.”Footnote 111

Early Capital Accumulation

With the financial help of Arthur Capel, who had already funded her first boutique in Paris, Chanel started making clothes as a sportswear designer in two elegant and aristocratic resort areas—Deauville in 1913 and Biarritz (where she established her first fashion house) in 1915—where many wealthy families found refuge in the midst of World War I. Deauville was regarded as the summer capital of France,Footnote 112 and Biarritz was fashionable, as it hosted royals from all over Europe—the perfect setting for luxury shopping.Footnote 113 Actresses and demimondaines of Balsan’s entourage endorsed Chanel’s early creations and secured publicity for her hats. Thus, in 1910, actress Lucienne Roger wore Chanel’s hats on the cover of Comoedia Illustré,Footnote 114 followed in 1911 by actress Jeanne Dirys (illustrated by the famous illustrator Paul Iribe).

In 1912, Gabrielle Dorziat, Royallieu habitué and high-profile actress, well known as a fashion trendsetter in Paris, helped popularize Chanel’s unique designs by wearing her hats in the play Bel Ami by Maupassant (with the costumes made by the well-known designer Jacques Doucet). She also modeled other Chanel creations in the magazine Les Modes, one of the most influential fashion periodicals before World War I. Cécile Sorel, one of France’s leading actresses, wore Chanel’s hats in the play L’Abbé Constantin and in American Vogue in 1918. High society women also started to take notice of Chanel’s work. In 1914, among the prominent clients of her shop in Deauville were Baroness Diane “Kitty” de Rothschild with her friend Cécile Sorel. Baroness de Rothschild—who declared “Coco Chanel not only a milliner of talent, but a [fashion] personality”Footnote 115—was a glamorous and influential member of Parisian society and was soon followed by other socialites such as Princess “Baba” de Faucigny-Lucinge, Pauline de Saint-Sauveur, and Antoinette Bernstein, wife to the fashionable playwright Henri-Adrien Bernstein.Footnote 116

According to Bourdieu the volume of the social capital possessed by an individual depends on the size of the network of connections he or she can effectively mobilize as well as the volume of the capital possessed by those to whom he or she is connected.Footnote 117 Chanel’s early success was built on forming an influential network of clients and champions. Through Etienne Balsan’s circle of actresses, demimondaines, and aristocratic sportsmen at Royallieu and then Arthur Capel’s access to the most fashionable echelons of Paris society, Chanel came into contact with socialites and clients whose aesthetic orientations matched her stylistic vision: straight and relatively short skirts, sweaters in sailor fashion, blouses, straw hats, and low-heeled shoes.Footnote 118 Women were finally dressed to enjoy outdoor activities, sandy beaches, tennis courts, walks, and parties. By supplying economic capital and mobilizing social contacts, these audiences helped Chanel expand her network and build reputation (symbolic capital), which she transmuted into economic capital as more and more women were eager to purchase her clothes. Indeed, in 1916, Chanel’s stores were so successful that, at the end of the year, she had a staff of three hundred employees working in her fashion house. Chanel repaid her loan from Boy Chapel and became financially independent.

Chanel’s growing business success stands in stark contrast to the ostracism of colleagues and critics she had to endure from the beginning of her career until the early 1920s. Indeed, Chanel’s progression was not a linear and uncontested process. Paul Poiret was among the first to perceive Chanel as a threat: “We ought to have been on guard against that boyish head. It was going to give us every kind of shock, and produce, out of its little conjuror’s hat, gowns and coiffures and jewels and boutiques.”Footnote 119 Professional dressmakers in general dismissed Chanel: Madeleine Vionnet used to derogatorily call her “that milliner,”Footnote 120 and Paul Poiret followed up “that boyish head” by later declaring that she had invented “la pauvreté de luxe.”Footnote 121 Having no institutionalized cultural capital (i.e., professional credentials), Chanel was also frequently criticized for her lack of technical knowledgeFootnote 122 and for relying on premières. Footnote 123 She was a bricoleur,Footnote 124 knew little about garment construction, and often failed to find the correct terms to explain what she wanted to her staff.Footnote 125 Print and fashion critics paid only tepid attention to Chanel’s style, instead favoring established designers who continued to offer designs that were a revival of the late eighteenth century—that is, when corsets, crinolines, pagoda hips, and tapered hems were the dominant fashion style.

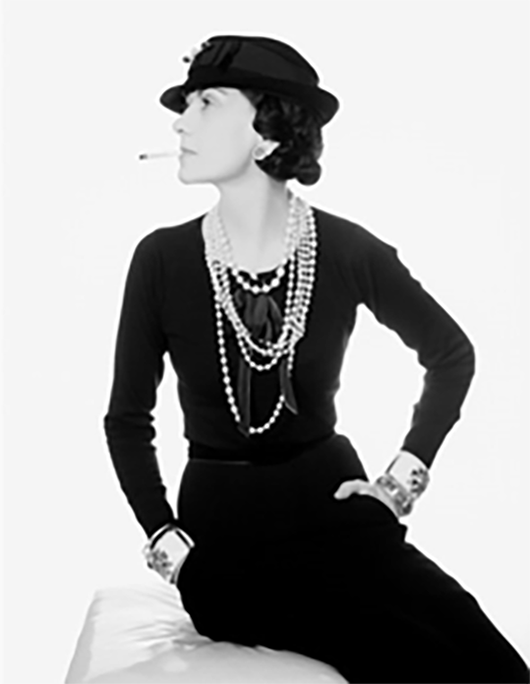

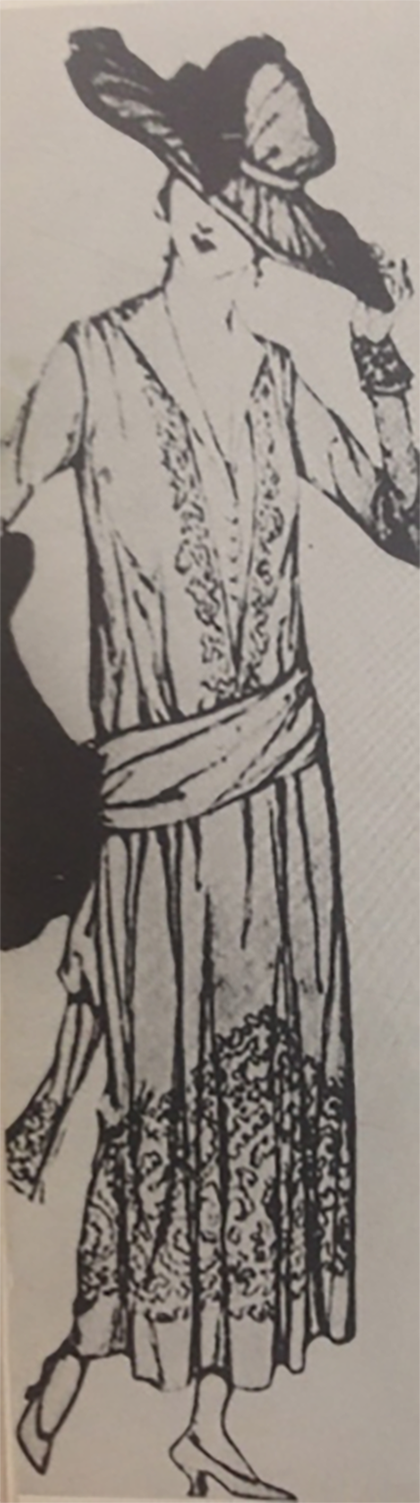

Interestingly, critical recognition for Chanel came first from North America rather than Paris when her designs appeared in 1916 in Harper’s Bazaar—one of the major American fashion magazines—which was the first to publish a photo of the chemise dress by Chanel (a simple gown of gray jersey with neither collar nor bodice, but a deep V-cut in front and a low sash, as illustrated in Figure 5) and then in American Vogue. Les Elegances Parisiennes first published a design by Chanel in 1917, although her name was misspelled (“Costumes de jersey—Modèles de Gabrielle Channel”). French critics did not openly support Chanel’s work until the early 1920s, when casual wear had become a major trend in French haute couture. Against this backdrop of suspicion if not open ostracism, World War I played a crucial role in accelerating the social changes that had started during the prewar years, creating a soil in which Chanel’s style could take root and thrive. Also, the connections Chanel established with other like-minded artists in Paris proved crucial to her journey.

Figure 5. Illustration of Chanel’s chemise dress from Harper’s Bazaar, March 1916.

Source: Davis, “Chanel, Stravinsky, and Musical Chic,” 434.

World War I and the Diffusion of Chanel’s Style

The outbreak of World War I offered women a unique opportunity to become emancipated and take a more active role in society. Recalling this macro-level change, Chanel noted: “One world was ending, another was about to be born. I was in the right place; an opportunity beckoned, I took it. I had grown up with this new century: I was therefore the one to be consulted about its sartorial style. […] When I went to the races I would never have thought that I was witnessing the death of luxury, the passing of the nineteenth century, the end of an era.”Footnote 126 The war initiated a process of liberation: with men at war, women were asked to work and, for the first time, had the opportunity to take on roles they had never held before. At a time when women were looking for a new social identity, Chanel’s style of simplicity, shorter skirts, and more comfortable materials matched their new lifestyle very well. She presented “her clothes as suitable for a new lifestyle that was being adopted by young women during and after the First World War.”Footnote 127

The war generated momentum for change by accelerating the emergence of a new style that challenged the established haute couture field. This effect is evident in the case of Paul Poiret—the most inventive designer of the early twentieth century and a key member of the fashion field during the prewar yearsFootnote 128— who was rapidly edged out of the field: after World War I, modernism was favored over ornamental fashion, and Poiret’s elaborate sense of luxury was overshadowed by the functional simplicity of designers like Coco Chanel.Footnote 129 Poiret eventually shuttered his business in 1929.

Conversely, these social transformations favored Chanel, whose clothes were particularly appropriate for women’s post–World War I lifestyle, and garçonne fashionFootnote 130 sanctioned her ultimate success. The notion of women as objects of possession became antiquated, and with the advent of new social customs (i.e., no more horse-drawn carriages, no servants, women’s new professional lives), the war led to a completely new conception of how to dress the female body. The war “played right into her [Chanel’s] hands, for nothing could prevent its giving women what had been previously beyond their grasp: liberty.”Footnote 131 Chanel created a practical uniform for the modern bourgeois women, helping them to redefine their position in society. In the late 1920s, Chanel’s designs were emblematic of the social changes that, after the war, had granted women more freedom: wearing shorter skirts and bobbed hair, drinking and smoking in public, driving cars. As Charles-Roux points out, women “needed to be able to move about on foot, to walk rapidly, and without encumbrance. This made the Chanel outfit the dress of the moment.”Footnote 132

Before World War I, fashion was a privilege of the elite (mainly aristocrats), and haute couture was the leading production model, even though only a small fraction of French women could afford it. French couturiers like Jacques Doucet, Charles Frederick Worth, Emile Pingat, and Paul Poiret were very influential, having ruled the fashion industry since the middle of the nineteenth century. The war dramatically amplified changes that had already begun to hit avant-garde circles but that quickly diffused through all of postwar society, thanks to the concomitant development of printing, advertising, and mass consumption.Footnote 133 When Chanel and “her cohorts burst upon the post-war world, their fashions immediately became inscribed in a debate about the war’s effect on gender.”Footnote 134 Freer in behavior and more independent, the femmes modernes adopted a silhouette “without breasts, without a waist, without hips.”Footnote 135 Traditional prewar fashion proved outdated when the taste for minimalism and a pared-down look gradually became the norm.

From the Margins to the Core of Haute Couture

Chanel cultivated her unique vision and gained early market recognition while working at the margins of French haute couture, where she did not have to face real conformity pressure from contentious peers and skeptical critics. But in 1919, at the end of the war, Chanel was ready to open her famous fashion house in Paris at 31 rue Cambon.Footnote 136 Arthur Capel, who had played a key role at the beginning of Chanel’s career by supporting her financially and who had left her £40,000—a fortune at the time—in his will (a sum that she inherited in 1919 when he died prematurely in a car accident),Footnote 137 was also fundamental in putting Chanel in touch with members of Paris’s vibrant avant-garde artistic circle. Pivotal among them was Misia Godebska-Sert,Footnote 138 who hosted an artistic salon in Paris and whose circle of friends included the Cubist painters Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, the founder of the Ballets Russes Sergei Diaghilev, and the poet and playwright Jean Cocteau. In 1893, Misia had married Thadée Natanson, editor of La Revue blanche, the bimonthly periodical of the intellectual avant-garde in Paris. She was considered “the spirit, indeed, the symbol of La Revue blanche”Footnote 139 and held a central position among the avant-garde artists who gravitated to her salon.Footnote 140 Chanel was introduced to Misia by Cécile Sorel (a friend of Capel) on May 30, 1917. Members of artistic circles usually meet through an acquaintance network centered on a gatekeeper (Misia in this case) who also recruits new members “based on complementary expertise, but getting along and fitting in matter most.”Footnote 141 Chanel was the first dressmaker to join this circle of artists and collaborate with them in developing a new, boldly modern, style.Footnote 142

Despite lacking an artistic background, Chanel shared with contemporary avant-garde artists the essence of the modern aesthetic that viewed street style as the foundation for a new art. She was at the forefront of this change, and the “slangy chic”Footnote 143—which became her trademark—set an example for artists across different fields “in which a popularizing style […] overruled abstraction and intellectualized decadence.”Footnote 144 For instance, the new music of the period, including Igor Stravinsky’s neoclassicism and Darius Milhaud’s lifestyle modernism, “comes into focus, and its characterization as an ‘art of the everyday’ is exposed as an unfinished view. Like Chanel’s cashmere cardigans, this was an art that went down to ‘the streets’ but the materials found there were filtered through an élite sensibility and reconstructed for a socially privileged audience.”Footnote 145 This cultural movement eventually promoted new aesthetic standards that emphasized geometric and simple shapes, symmetrical motifs, and modern materialsFootnote 146 used in all applied arts.

During the 1920s, Chanel’s style became increasingly central within this growing movement as it synthesized all the dominant aesthetic elements of its time: simple lines and the abandonment of ornament, which mirrored a similar change in all the decorative arts. Consistent with the modernist ethos, which was defined in opposition to the past, Chanel made unconventional stylistic choices—abandoning expensive and heavy fabrics in favor of jersey (not elegant, cheap, impossible to decorate with embroidery)—which led to simplified designs with architectural lines and a de-sublimation of fashion. According to social philosopher Gilles Lipovetsky, these stylistic choices found parallels in Picasso’s and Braque’s (contemporaneous) visual art creations.Footnote 147 As Cocteau noted, Chanel worked in fashion according to the same rules as the painters, musicians, and poets with whom she interacted very closely and, in some cases, collaborated with for years.Footnote 148 Chanel’s combination of pure lines and plain colors drew comparisons with the Cubist Analytic phase and its use of humble materials and muted colors. Purity, precision, and simplicity were also the basic characteristics that Chanel’s designs shared with the new music, especially Stravinsky’s musical structure with its emphasis on repetition and architecture over ornamentation, and the idea that elements of everyday life should be the basis of sophisticated garments or music compositions. Vogue acknowledged that the most important designers who had emerged in the 1920s were “the two most involved with new movements in other fields—Chanel, whose circle included Picasso, Cocteau, and Stravinsky, and the new Schiaparelli, whose friends were surrealists.”Footnote 149

The homology between avant-garde artists and Chanel fostered the recognition and diffusion of her style. This homology is evident from her intense collaborations with artists from different fields who shared similar dispositions (e.g., taste, aesthetic orientation, and style).Footnote 150 For instance, Chanel became actively involved in the theater world, working with Jean Cocteau for fourteen years. Cocteau first chose Chanel for the costumes and Picasso for the set of his 1922 adaptation of Antigone, a fresher version and a modern reduction of Sophocles’s Greek tragedy. Critics acclaimed Chanel’s costumes, and many reviews in fashion magazines such as Vogue, Gazette du Bon Ton, and Vanity Fair, among others, praised her work.Footnote 151 This collaboration had the effect of enhancing her status in Paris. However, the artistic consecration of her work came in 1924 when Sergei Diaghilev, the founder of the Ballets Russes, asked her to design the costumes for Le Train Bleu. Diaghilev imbued his productions with the works of avant-garde contemporary artists such as Pablo Picasso, Jean Cocteau, Henri Laurens, and Darius Milhaud. Cocteau wrote the libretto, Picasso painted the curtain, Laurens constructed the set, Milhaud composed the music, and Nijinska created the choreography. Chanel dressed the actors in jersey costumes, bringing reality and her garçonne-style hallmarks to the stage. For the first time, dancers appeared onstage wearing street clothes, as Chanel used sportswear copied from her collection—swimsuits as well as tennis and golf uniforms. With Le Train Bleu, “the lens of lifestyle modernism was trained on fashion itself.”Footnote 152 Critics unanimously praised Chanel’s creations, reinforcing her centrality within the modernist era. As Cocteau declared, “Chanel was to couture what Picasso was to painting.”Footnote 153

Consistent with research on collaborative circles, it is through these collaborations that like-minded artists develop a common vision while preserving their own artistic freedom. By supporting and legitimating the work of their members, collaborative circles enhance the cultural capital of each member and facilitate its conversion into symbolic and ultimately economic capital. The critical acclaim that Chanel received for her theatrical work increased her status within the fashion industry, but also contributed to her commercial success. Relationships among members of collaborative circles are multifaceted, as they offer emotional and material support to their members. In 1920, for instance, Chanel financed Diaghilev’s creative project for 300,000 francs (more than $150,000 in cash today). Recalling that episode, Chanel said: “I wanted him to mount ‘The Rite of Spring,’ I told him: I put a condition on you, that no one knows that I gave you money to do this.”Footnote 154

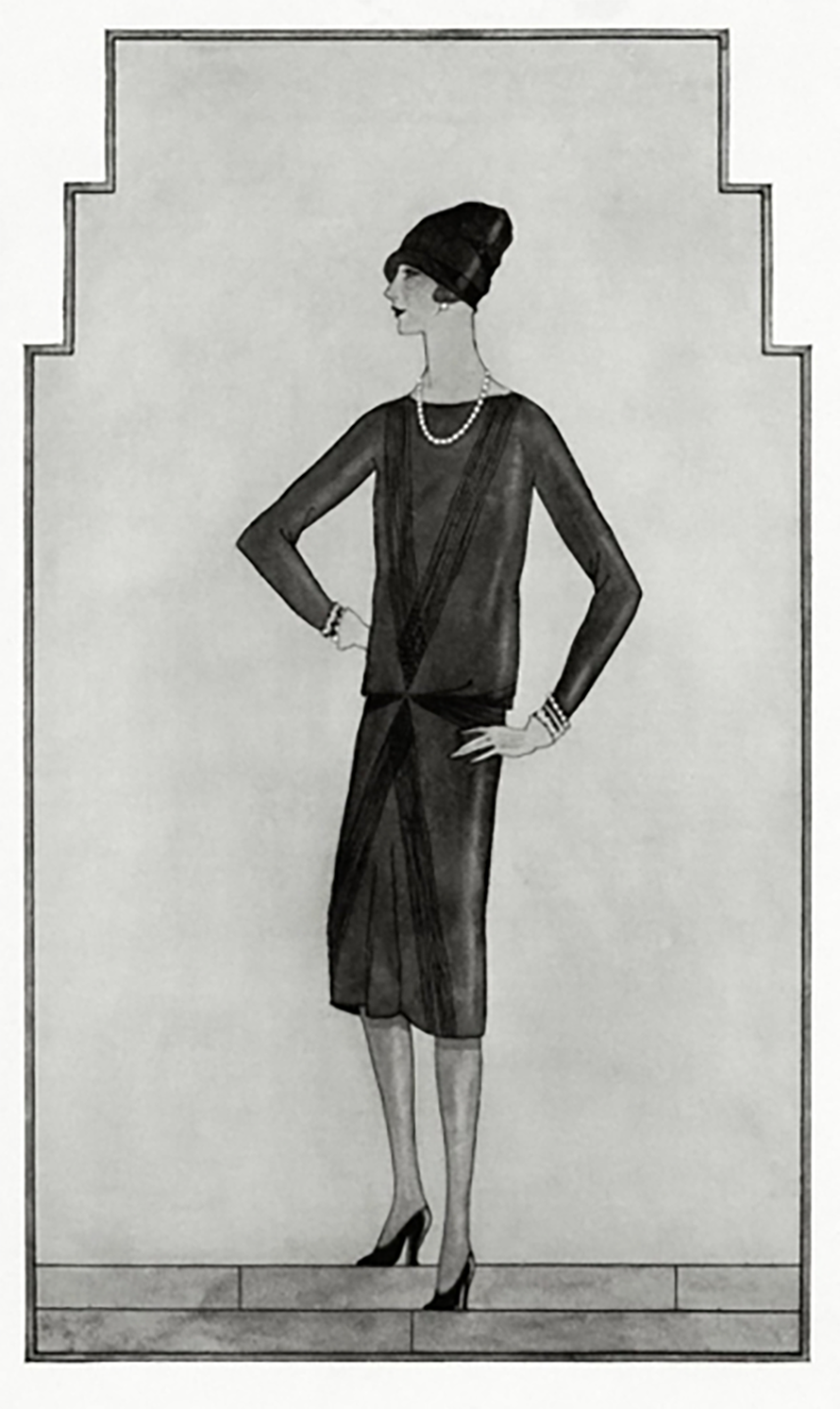

In 1926, Chanel presented the “little black dress” (see Figure 6)—a simple and versatile dress suited for any occasion—that embodied the idea of functionality that was at the core of the art deco movementFootnote 155 and suddenly became a symbol of the modern age.Footnote 156 Often cited as Chanel’s contribution to the fashion lexicon, it has survived to this day as the modern woman’s uniform. In presenting this simple dress, Chanel emphasized its blank-slate versatility: It could be worn during the day and in the evening, depending on how it was accessorized. Chanel also endorsed the appropriateness of black several years before any other designers saw its power. American Vogue compared this frock to another icon of modernity, the Ford Model T, the automobile for the mass market. On October 1, 1926, American Vogue hailed this creation as “the Ford signed Chanel,”Footnote 157 predicting that Chanel’s little black dress would become a uniform for all women.Footnote 158

Figure 6. Illustration of Chanel’s “little black dress” from American Vogue, October 1926.

Source: https://www.vogue.com/article/from-the-archives-ten-vogue-firsts.

This dress was soon copied in all price ranges, more than any other dress. Functionality, modernity, and simplicity were all key elements of her fashion, but also of music, visual art, theatre, and other artistic fields. Chanel’s creations evoked the spirit of contemporary art movements with an emphasis on functionality and purity of line, aligning Chanel with the principles of art deco.Footnote 159 The institutionalization of this new fashion coincided with French women accepting the idea of boyish-looking figures and an overall reassessment of the meaning of being fashionable. As the Marquise Boni de Castellane—at the time a notorious fashion personality—noted, prewar manners and mores did not exist anymore as “women no longer exist: all that’s left are the boys created by Chanel.”Footnote 160 Not surprisingly, Poiret left the fashion business: he did not accept the idea that women could be dressed “like a flock of school-girls as if in an institutional uniform.”Footnote 161 Figure 7 shows the diffusion of Chanel’s style in women’s attire with variations of her original little black dress and typical hat.

Figure 7. Little black dresses in 1920s.

Source: http://artdecoblog.blogspot.com/2009/10/little-black-dresses-1920s.html.

As Picasso aimed to affect society instead of simply talking to an intellectual elite, so Chanel believed that fashion “in its broadest interpretation, seeks to be adopted by the masses, and incrementally change the way they dress, for the better.”Footnote 162 This explains why Chanel relied on multiple channels to help spread her style and reach a wider audience. In the early 1930s, for instance, Chanel recognized the growing importance of cinema in the popular culture, as opposed to the more elitist theatre, and realized it was a medium through which new models and styles could be widely diffused. From 1931 to 1934, she started working with Samuel Goldwyn on the wardrobes for his Hollywood productions.Footnote 163 Around this time, Chanel met Carmel Snow of Harper’s Bazaar, Margaret Case of Vogue, and Condé Nast, the publisher of Vogue in New York. Once in New York City, most importantly, Chanel became aware of new business models in the retail industry: she discovered the department stores (e.g., Macy’s, Saks, and Bloomingdale’s) and a discount bazaar in Union Square: Klein’s.Footnote 164

In the 1930s, fashion underwent a major transformation that coincided with a new change in taste. Chanel realized that “she had nothing to say to the new fashion world, society had evolved in a way that was inconsistent with her ideas and, in order to avoid a slow exit from the market, it was necessary to break with it. Like an artist who stops creating.”Footnote 165 Thus, in 1939, on the eve of World War II, Chanel decided to close her fashion house and the couture business. Only the boutique at 31 rue Cambon remained open: perfumes and accessories continued to be sold throughout the war. In fact, her brand remained very strong with the production of perfumes, cosmetics, and fabrics through the branches Chanel Parfums and Tissus Chanel.Footnote 166

Toward the end of World War II, however, Chanel faced a major setback because of her suspected involvement with the Nazis. Chanel, who had demonstrated anti-Semitic views during the interwar years (e.g., she had a five-year-long relationship with the Duke of Westminster, an outspoken anti-Semite), acted as a spy in a Nazi operation in Occupied Europe with Baron von DincklageFootnote 167 and tried to take advantage of the Nazi laws to regain full ownership of Les Parfums Chanel S.A.Footnote 168 As a businesswoman, she probably established such relationships to maintain her high standing in French society if Germany won the war. Her many connections to powerful personalities helped Chanel protect her reputation: Interrogated in 1944 after the liberation of Paris, she was in fact soon released due to the lack of evidence of her collaborative activities and apparently thanks to the intervention of her friend the British prime minister Winston Churchill.Footnote 169

In 1954, after fifteen years of voluntary retirement, Chanel decided to come back to haute couture at the age of seventy-one, with the financial backing from the profits of her perfume, Chanel No. 5. During her retirement, spent in Switzerland, Paris, and New York, she had stayed in touch with fashion critics (e.g., Carmel Snow, editor of Harper’s Bazaar) and celebrities,Footnote 170 and for a decade spanning the 1960s and 1970s, she committed herself to refining the “perfect tailored suit” for women, searching for an ideal harmony among the pieces (i.e., a jacket, a skirt, and a dress or a sleeveless shirt) that compose the suit—even though conceptually it was a unique garment. Figure 8 shows Chanel’s suit—arguably the most iconic outfit of the sixties—worn by Jackie Kennedy on the day her husband, President John F. Kennedy, was assassinated. In 1957, Chanel received a fashion award as the most influential designer in the twentieth century from Neiman-Marcus,Footnote 171 but she refused both the “Fashion Immortal” award from the Sunday Times and the Légion d’honneur, because both honors had been previously granted to other fashion designers. In 1968, Time estimated that Chanel’s fashion business, perfume included, with about four hundred employees on its payroll, was bringing in more than $160 million per year.Footnote 172 Chanel died on Sunday, January 10, 1971, at the age of eighty-eight. Figure 9 summarizes Chanel’s entrepreneurial journey through a chronological representation of key facts, events, and outcomes from the year she was born to her retirement on the eve of World War II.

Figure 8. Jackie Kennedy wearing a Chanel suit, 1963.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pink_Chanel_suit_of_Jacqueline_Bouvier_Kennedy.

Figure 9. Key events in Chanel’s innovation journey.

Discussion and Conclusion

References to the role of outsiders as innovation catalysts are present across a variety of studies. Yet the paradox is that the same social position that helps outsiders to pursue imaginative projects that depart from prevailing social norms also constrains their ability to obtain support and recognition for their innovations. In fact, some scholars have recently referred to this conundrum as the “outsider puzzle”Footnote 173 or “the paradox of peripheral influence.”Footnote 174 Chanel’s case is no exception to this general observation. Being an outsider, who lacked formal education and had not apprenticed to an established fashion house, and a woman approaching a mature and stable field (Parisian haute couture) dominated by male fashion designers, she was an unlikely contender.Footnote 175 Yet Chanel’s position at the margins of the fashion field shaped the formation of her cultural capital in a unique way, exposing her to unusual stimuli and enabling her to defy pressures to conform to Parisian haute couture’s dominant canons. Because of her structural position, in other words, Chanel had the creative freedom to experiment with radical ideas: creating a functional dress with no corset and under which the body was merely suggested and imbuing her creations with a new notion of “natural” that was foreign to haute couture.Footnote 176

Chanel’s unique disposition also implied a very strong drive—she worked relentlessly to realize her unique vision—as well as remarkable powers of persuasion and social skills. Social skills encompass the ability to persuade pivotal individuals to offer support—in short, the skill “to induce cooperation in others.”Footnote 177 Evidence of Chanel’s social skills is her ability to ingratiate herself with several highly visible and powerful members of French society. Leveraging her social skills, Chanel succeeded in converting her embodied cultural capital into the economic capital needed to start and run her business, as well as the symbolic capital needed to fuel her status and visibility, despite facing strong opposition from field insiders. Chanel was indeed an accomplished relationship builder, supporting Charles Harvey, Jon Press, and Mairi Maclean’s observation that “cultural variety and social network variety are potentially valuable business resources.”Footnote 178 But it would be very hard to understand Chanel’s rise to the top of the international fashion field without accounting for the fit between her disposition and the meso- and macro-level historical context in which she operated. In particular, we identified two critical factors that sustained and strengthened Chanel’s progression toward the core of French haute couture: World War I and the rise of modernist movements in the arts. These two factors unfolded in a direction that worked in favor of Chanel’s stylistic and cultural vision, enabling her creations to gain exceptional recognition and acclaim.

First, we have shown that exogenous shocks or other dramatic events can alter the intellectual climate,Footnote 179 disrupt existing relations,Footnote 180 and raise awareness of extant and alternative logics, opening the way for the entry of new players and practices into the field.Footnote 181 In Chanel’s case, World War I was the exogenous shock that precipitated her entry into the fashion world by recasting traditional feminine fashion, replacing it with an austere elegance hitherto associated with the male dandy and based on a male model of power.Footnote 182 The post-conflict period was no longer a time for extravagance, and the deprivations of war made women more receptive to simplicity than they might otherwise have been. Chanel created the uniform for the modern bourgeois woman, an independent working woman like herself. Women confirmed her conviction, and in 1914, at the end of the first summer of the war, Chanel had her first commercial success and earned 200,000 gold francs.Footnote 183 As Mary Louise Roberts noted: “The new, more fluid style was above all—like the modern woman herself—a creation of the war.”Footnote 184 Second, our historical analysis reveals how the existence of a homologous social space is a crucial precondition for outsiders to marshal different forms of capital.Footnote 185 In line with the sociology of ideas, the emergence of new ideas should be explained by placing them in their historical context and identifying the social processes through which they emerged and evolved.Footnote 186 Besides surveying the broader context in which challengers (and their ideas) are located, such explanations emphasize the influence of mediating institutional factors among which social audiences play a critical role. Our evidence confirms that Chanel benefited from the homology between her fashion style and the core principles that animated influential modernist artistic audiences, particularly some increasingly prominent Parisian collaborative circles. Her innovations resonated with the French artistic avant-garde, who promptly endorsed the philosophy behind her novel designs and helped her forge a modernist ideal centered around comfort, geometric forms, and the rejection of ornamentation—a trend that was increasingly observable in many decorative arts. By forging ties with modernist artists and collaborating with some of them for years (e.g., Picasso, Cocteau, and Diaghilev), Chanel was able to push her style through with the backing of collectively owned social capital. Thanks to her deep involvement with social circles embedded in the modernist art movement, her creations received public display in theatrical performances, ballets, and movies, thereby facilitating the transmutation of cultural capital into symbolic (fame) and ultimately economic capital (commissions).

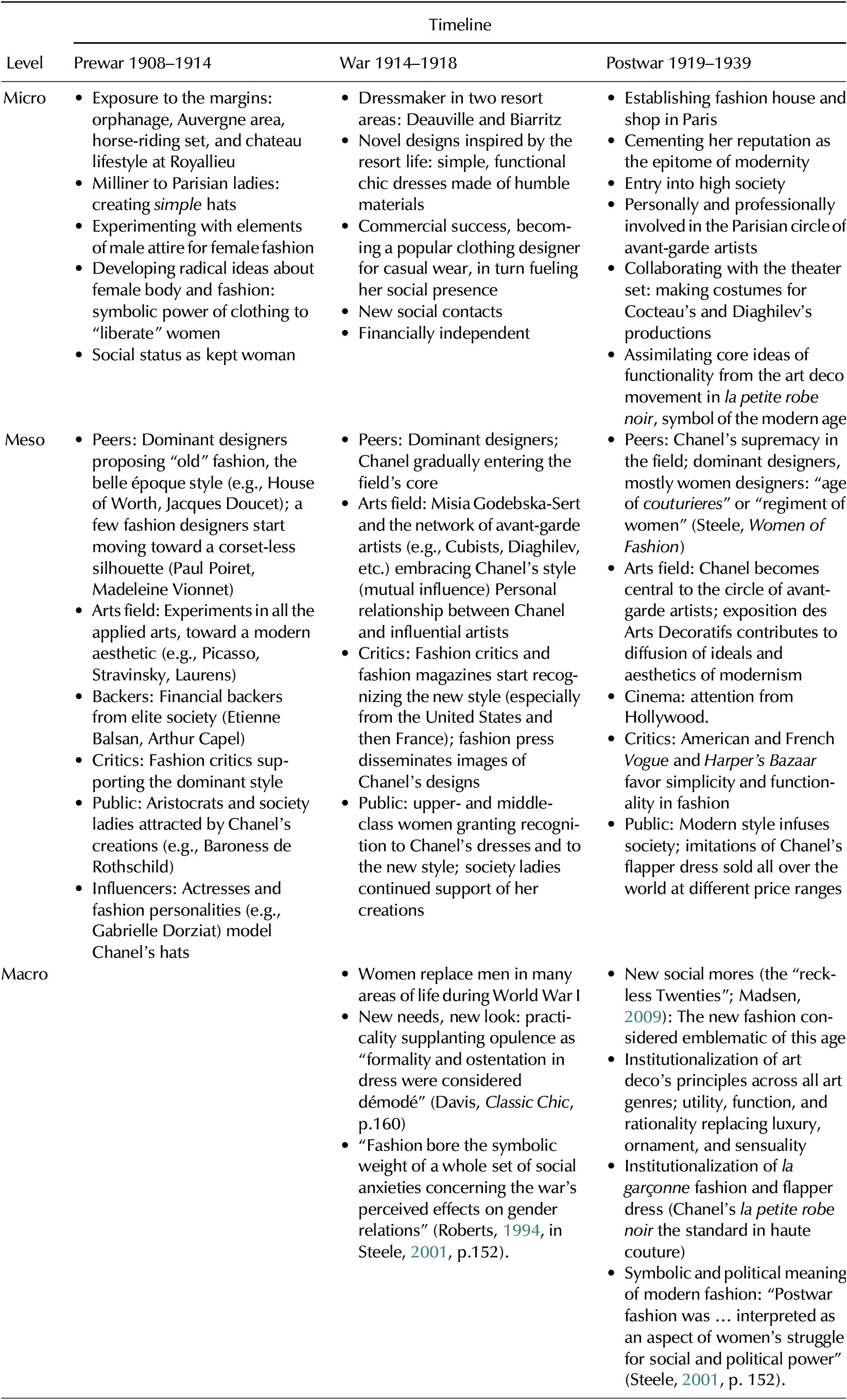

In taking Coco Chanel as our exemplar and placing her in a Bordieuan capital theoretic model of entrepreneurship, we followed the lead of recent history-oriented scholarship that has illuminated the processes of capital deployment and accumulation of such iconic figures as Andrew Carnegie,Footnote 187 William Rushworth II,Footnote 188 and William Morris.Footnote 189 In line with this line of work, our study confirms the importance of each of the four forms of capital and their interdependence when deployed in the struggle for social advancement. The bulk of the entrepreneurship literature on various forms of capital, however, has been silent on the capital accumulation dynamics of genuine outsiders and has paid only scant attention to the complex relations and mutual influence between innovation efforts and the social context in which those efforts unfold.Footnote 190 This demands a close look at the recursive influence of micro-, meso-, and macro-level forces shaping an innovator’s journey, from the moment novelty is introduced to when it takes hold and propagates. In practice, work in this area has remained bound to subdisciplinary conventions that channel some scholars to the micro-level and others to the macro-level, thus failing to fully take into account the interlocking relations of individual human lives with forces operating across levels of analysis. By contrast, our historical analysis of Chanel’s journey from the margins to the core of the fashion field, while not oblivious to her unique habitus and remarkable social skills, suggests that there is much to gain analytically by attending to how the social, economic, and cultural forces to which actors are historically exposed shape the way in which innovators mobilize, convert, and ultimately accumulate various forms of capital. We contend that only by examining the mutually constitutive relationships between these forces operating at different levels of analysis can one properly appreciate the conditions that jointly affect the journeys to the top taken by those outsiders who emerge as dominant economic actors. The adoption of a historical approach is especially useful for this purpose, as it is well-suited to expose the interplay of micro-, meso-, and macro-levels over time. This, in turn, helps illuminate why those efforts may be unconceivable during certain historical phases, yet comprehensible and perceived as legitimate in others. Table 2 summarizes the different forces that shaped Chanel’s entrepreneurial journey.

Table 2. Chanel’s entrepreneurial journey (1908–1939): a multilevel view a

a World War I is the dividing line between the “old” and “modern” eras.