Introduction

Varicella, caused by the varicella-zoster virus, is an acute infectious disease that primarily affects infants and preschool children [Reference Heininger and Seward1]. The disease is more prevalent in winter and spring and is highly contagious, with infected patients being the sole source of transmission. Contagiousness begins 1–2 days before the onset of the disease and lasts until the rash has reached the dry and crusted stage, with transmission occurring through contact or inhalation of droplets.

Varicella is a highly contagious disease to which the population is universally susceptible. In 1974, a live attenuated varicella vaccine was developed in Japan [Reference Takahashi2]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends achieving and maintaining vaccine coverage of ≥80% to further reduce the incidence and morbidity associated with varicella [Reference Anon3]. In 1998, China introduced the self-paid varicella vaccine [Reference Xu4], which has been regarded as an effective measure to prevent and control the spread of the disease. Varicella vaccination is cost-effective [Reference Feng5]. Because varicella vaccination is self-funded, and in order to reduce the burden of disease caused by varicella, some provinces and cities in China, such as Shanghai and Nanjing, have included varicella vaccine in their local Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) and have made the vaccine available to children free of charge [Reference Feng5]. Different immunization strategies require different amounts of financial support, and the choice of one or two doses is a matter of concern. However, different study pairs presented different results, both for one and two doses, which may be related to the vaccination rate and the characteristics of the vaccinated population [Reference Hu6–Reference Mahamud8]. More research is needed on the effectiveness of a free vaccination policy in reducing the incidence of varicella.

To better prevent varicella, since December 2018, Wuxi has been providing free varicella vaccination for resident children born after December 2014, with two doses at 1 and 4 years of age, making Wuxi the first city in Jiangsu province to implement this initiative. The aim of this study is to evaluate the VE of varicella vaccine in the real world and provide evidence for the development of varicella vaccine strategy.

Materials and methods

Surveillance system

Wuxi, situated in the southern part of Jiangsu province, China, consists of eight districts and two counties, with a resident population of around 7.48 million and approximately 50 000 births per year. Statutory infectious diseases in Wuxi are reported through the China Information System for Disease Control and Prevention. Although varicella is not a legally reported infectious disease in China, in 2017, Jiangsu province required medical institutions to report suspected cases of varicella with reference to the requirements of Class C infectious diseases and to conduct regular inspections. Suspected cases are defined as the presence of spots, papules, and herpes on the skin and mucous membranes; the location of herpes is superficial, oval, and 3–5 millimetres in diameterm and they are thin-walled and easy to break and may be accompanied by systemic symptoms such as fever, headache, or sore throat. Vaccination records are maintained in the Jiangsu Province Vaccination Integrated Service Management Information System (JPVISMIS), where each individual is assigned a unique identifier at the time of vaccination, and the child’s demographic information and immunization history are recorded.

Data resources

In 2022, we conducted a systematic study to compile varicella case profiles from the past decade. This entailed collecting data on 70 412 reported varicella cases in Wuxi, spanning the years from 2012 to 2021. To ensure the observational data maintained a longitudinal perspective of 5–10 years, we employed a screening process that relied on fundamental criteria, including household registration, valid ID numbers, and age. This meticulous screening led us to include 15 686 cases born between 2012 and 2016, for which we successfully obtained immunization history information through the JPVISMIS system (Figure 1). According to the varicella immunization schedule, we defined timely vaccination as one dose of varicella vaccine within 2 years of birth.

Figure 1. Flowchart for case inclusion

We queried the JPVISMIS records for the cohort of children born in 2012–2016, totalling 382 397. Querying the immunization history revealed that the number of timely vaccinations was 207 904, the number of those who received only the first dose was 113 583, the cumulative number of those who received the second dose was 204 922, and the cumulative number of vaccinations was 318 505.

Statistical analysis

This study describes vaccination coverage and varicella incidence, presenting qualitative data as frequency (%)and uses a screening method to assess the protective effect of the vaccine. Person-years were calculated using the simple life table method, that is, individuals entering the cohort in the year of observation were counted as 1/2 person-years, and those who were lost to visit or had a final outcome were also counted as 1/2 person-years. The onset of varicella was assumed to be the final outcome.

The screening method, initially proposed by Orenstein in 1984, was first utilized to determine whether the VE was within the expected range. With its low cost and relative ease of implementation, screening methods have gained increased usage in the evaluation of VE [Reference Orenstein9].

A screening method was used to calculate VE using data on case and vaccination rates by dose. In estimating the effect of one dose of vaccine, people who had received two doses of vaccine were excluded from the calculations of case rates and the vaccinated population. Similarly, people who had received one dose of vaccine were excluded from the calculation of the effect of two doses of vaccine. The formula for calculating the screening method is as follows [Reference Greenland, Thomas and Morgenstern10, Reference Rodrigues and Kirkwood11]:

VEi represents the vaccine effectiveness (VE) of one or two doses, while PCVi and PPVi, respectively, denote the proportion of cases vaccinated (PCV) with i doses and the proportion of population vaccinated (PPV) with i doses.

PCVi refers to the proportion of cases who received i doses of vaccine among the total number of cases who received i doses and those who did not receive any dose. PPVi refers to the proportion of the population who received i doses of vaccine among the total number of people who received i doses and those who did not receive any dose.

The data were collected using Microsoft Excel (version Microsoft 365) and analysed using SPSS (version 18.0). Differences in proportions were calculated using chi-square tests, while onset time was compared using t-tests or analysis of variance, with a significance level of 0.05.

Results

Case characteristics

A total of 382 397 children with 15 686 cases of varicella were included in this study. From 2012 to 2021, the number of varicella cases increased first and then decreased, with the peak in 2018 (Figure 2). Due to differences in time of exposure, the later the birth cohort, the lower the number of cases, with a gradual decrease in the mean age of onset (χ2 = 5 399.385, P = 0.000), and a higher number of cases in males than in females (χ2 = 15.45, P = 0.004). The mean incidence rate for the birth cohort was 55.50/10 000 person-years, ranging between 27.86/10 000 person-years and 68.77/10 000 person-years (Table 1).

Figure 2. The annual incidence of varicella

Table 1. Incidence of varicella in different birth cohorts in Wuxi City, 2012–2021

To further clarify the average age of onset, we chose the incidence of 0–5 years old in each cohort for analysis, and the average age of onset still showed a downward trend, especially since the 2014 birth cohort, the average age of onset showed a significant decline (Table 2).

Table 2. The incidence of varicella in 0–5 years old in different birth cohorts

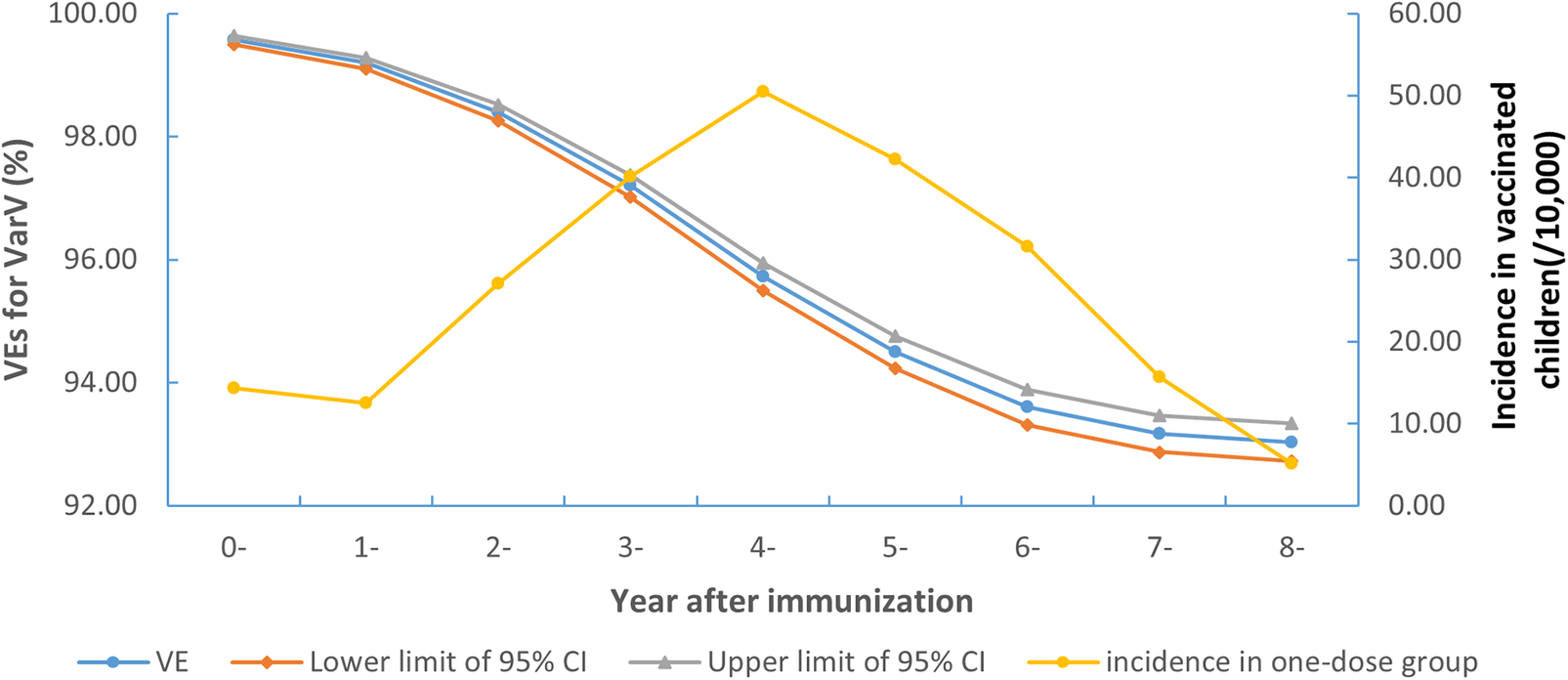

The incidence rate of breakthrough varicella cases in the one-dose vaccinated population increased during the first 4 years, reached a peak in the fifth year, and then began to decline in subsequent years (Figure 3).

Varicella vaccination coverage

Out of 382 397 children, 207 904 were vaccinated in time with an average timely vaccination rate of 54.37%. One dose of vaccination was completed by 318 505 children, with a cumulative coverage of 83.29%. A total of 204 922 children received two doses of vaccine, with an average coverage rate of 53.59%, and the two-dose coverage rate has been rising year by year (Table 3).

Table 3. Coverage rate of one dose and two doses varicella vaccine in different birth cohorts

Figure 3. Morbidity and post-immunization VEs in children who received only 1 dose of vaccine between 2012 and 2021 in Wuxi

Vaccine effectiveness of varicella vaccine

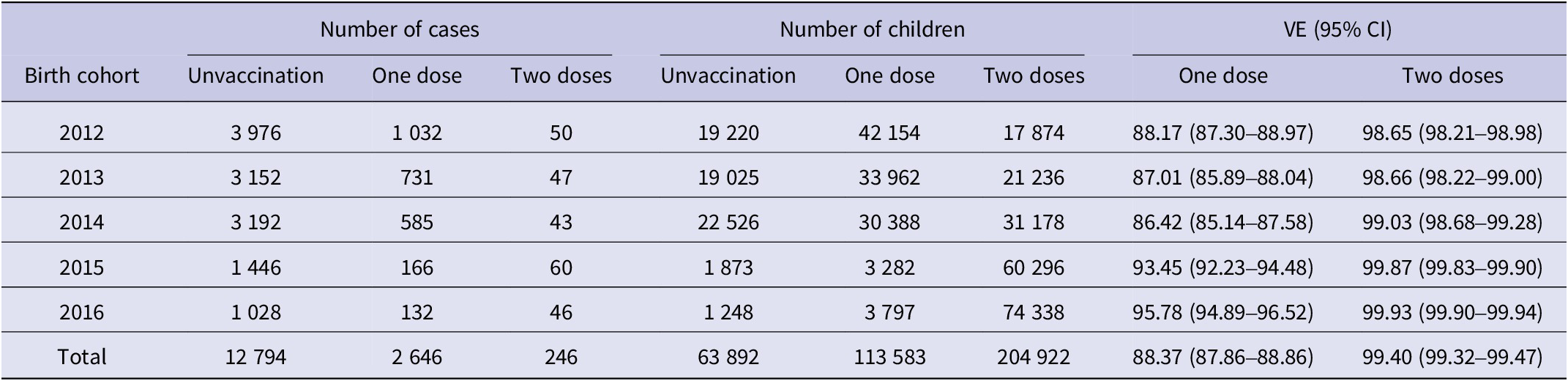

Of the 15 686 varicella cases, 12 794 (81.56%) did not receive varicella vaccine, 2 646 (16.87%) received one dose of varicella vaccine, and 246 (1.57%) received two doses of varicella vaccine. The VE of the single-dose varicella vaccine decreased and then increased in the five birth cohorts, with a minimum value of 86.42% and a maximum value of 95.78%. The overall VE was 88.37% (95% CI: 87.86–88.86%). The effectiveness of the two-dose vaccine increased year by year, with a minimum of 98.65% and a maximum of 99.93%. The overall effectiveness of the two-dose vaccine was 99.40% (95% CI: 99.32–99.47%). In each cohort, the VE was higher with two doses than with one dose (Table 4).

Table 4. Estimate the vaccine effectiveness of one dose and two doses varicella vaccine in different birth cohorts in Wuxi City, 2012–2021

The protective efficacy of one dose of varicella vaccine declined with time, decreasing from 99.57% (95% CI: 99.50–99.63%) in the first year to 93.04% (95% CI: 92.73–93.33%) in the eighth year (Figure 3).

Discussion

The internet-based big data analysis in China Information System for Disease Control and Prevention enables a comprehensive collection of varicella cases, providing a robust and reliable dataset for analysis [Reference Sun12], which, combined with the complete immunization history recorded in the JPVISMIS, further enhances the accuracy and reliability of our results. The vaccination rate for one dose of varicella vaccine in Wuxi has been stable at around 70% for many years and the estimated VE results for the screening method are stable and within the expected range [Reference Moberley13].

The study showed a significant increase in vaccination rates in both cohorts in 2015 and 2016, and the increased vaccination rates led to a significant decrease in varicella incidence, providing strong evidence for the protective effect of the vaccination programme [Reference Nguyen, Jumaan and Seward14, Reference Sheridan15]. The reduction in the average age of onset also demonstrated the protective effect of the vaccine. Children born after December 2014 can receive two doses of varicella vaccine at 1 and 4 years of age, which has reduced incidence and led to an increase in the proportion of cases in the younger age group who have not been vaccinated.

The results showed that the VE of one dose ranged between 88.17% (87.30%–88.97%) and 95.78% (94.89%–96.52%), with a mean of 88.37% (87.86%–88.86%), which is at a similar level to similar studies in China [Reference Xu16]. This study was conducted in an environment with high natural exposure and transmission rates of varicella, where exogenous exposure leads to a long-term boost in immunity in vaccinated individuals and may overestimate the effect of one dose of vaccination [Reference Yin17]. The VE for two doses ranged between 98.65% (98.21%–98.98%) and 99.93% (99.90%–99.94%) with a mean of 99.40% (99.32%–99.47%), with results similar to those of a study in the United States [Reference Shapiro18].

In this study, the protective effect of one dose at around 90% can effectively prevent varicella disease [Reference Leung, Broder and Marin19], which is similar to the results of a study in Beijing [Reference Lu20]. Given that one dose can also provide high protection, one-dose therapy is recommended if vaccine supply is limited or cost concerns are raised [Reference Zhou21],and two doses of booster if needed, for example, post-exposure prophylaxis [Reference Lin22]. Currently, many countries promote the use of two doses of varicella vaccine, including the United States [Reference Marin23] and China [Reference Pan24], because it improves immunity and helps control the spread of the disease. These results suggest that two doses of varicella vaccine provide strong protection against the disease and support the current vaccination program in Jiangsu province [Reference Wang25].

The VE of one dose of varicella vaccine was 99.57% in the first year but dropped to 93.04% after 8 years. Although the VE decreased over time, it still had a high protective effect. The results of many studies are inconsistent regarding the decline in VE over time. Some studies suggest that VE declines substantially within 5–10 years, whereas others suggest no sign of waning over time [Reference Baxter26]. The procedure for the second dose of immunization varies between countries and regions: 4–6 years in the United States [Reference Marin23], 5–6 years in most European countries [Reference Bonanni27], and 4 years in Beijing [Reference Suo28] and Wuxi [Reference Wang29], China, in relation to the long-term effects and breakthrough cases of varicella VE. Breakthrough infections increase around 4 years after vaccination [Reference Huang30], and according to our VE study, even longer intervals of vaccination, such as the eighth year, still provide good protection, similar to other studies in Jiangsu province [Reference Sun31].

Limitations

The study does have certain limitations that must be acknowledged. First, from 2017 to 2020, due to the policy adjustment and COVID-19 epidemic, the number of cases in each year fluctuated greatly, and the risk faced by each birth cohort also changed, which may affect the VE. Some COVID-19 epidemic measures, such as mask wearing and quarantine measures, have reduced the incidence of respiratory diseases, and the number of varicella cases has also decreased [Reference Tang, Lai and Chao32, Reference Tanislav and Kostev33], which may overestimate VE. Second, as the second dose of varicella vaccine is typically administered after 4 years of age, the follow-up period for the two doses in this cohort was relatively short, which limited the ability to conduct an in-depth analysis of the vaccine’s long-term efficacy. Further research will be done to fully understand the importance of the long-term protective effects of vaccines, as well as qualitative research on parents in terms of perceived effects, vaccine hesitancy, and adverse reactions.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated a significant increase in vaccination rates in the birth cohort following the implementation of a free varicella vaccination strategy, with one-dose vaccination rates increasing from approximately 75% to approximately 98% and two-dose vaccination rates increasing from approximately 30% to approximately 93%. Varicella vaccine demonstrated excellent VE values, with an average VE value of 88.37% (87.86%–88.86%) for one dose and 99.40% (99.32%–99.47%) for two doses. Although the VE values decreased over time, from 99.57% in the first year after one dose of vaccine to 93.04% in the eighth year, the vaccine remained highly effective.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S095026882400102X.

Data availability statement

Data available within the article or its supplementary materials.

Author contribution

Administrative, technical, or material support: X.W. and Y.S.; Concept and design: S.X., Z.X., and Q.W.; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: X.W. and Y.S.; Drafting of the manuscript: S.X., Z.X., and L.Z.; Obtained funding: S.X. and Y.S.; Statistical analysis: S.X., L.Z., and M.Y. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. And that all authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work and approve the version for publication.

Funding statement

This study is supported by the Medical Development Discipline Foundation of Wuxi (FZXK2021010).

Competing interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.