1. Introduction

In 2019, US Congressional Democrats announced the creation of a new tool – the facility-specific Rapid Response Labor Mechanism (RRM) – in the revised North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), known in the United States as the US–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA). The RRM allows a government to take action against a worksite in another country if it believes that workers are being denied their right to organize and bargain collectively. The inclusion of the RRM was seen as the primary reason for the broad bipartisan support the USMCA garnered. It was seen as the commencement of a new era for trade and an important step forward for progressives – who had been increasingly critical of US trade agreements – as even organized labor in the United States supported the USMCA.

This article investigates the RRM and is organized as follows. Section 2 begins with an outline of the political–economic events in the United States and Mexico that led to the countries agreeing to this unique tool. It describes the importance of the North American automotive supply chain and the sector's protests that drove the Trump administration's renegotiation of the NAFTA, which led to the birth of the RRM.

Section 3 reviews the underlying problems the RRM is purportedly designed to tackle: the inability of Mexican workers to unionize and bargain collectively to overcome monopsony power. It explains the importance of Mexico's labor reform to the renegotiation of the NAFTA and to the first few years of the USMCA, a reform process that policymakers could ultimately use the RRM to support.

Section 4 describes how the RRM works and analyzes the penalties the RRM sets out that may incentivize actors in Mexico that otherwise may be reluctant to go along with the labor reforms. It also documents the considerable financial and human resources the US and Mexican governments have deployed to operationalize the RRM and complement the Mexican government's own efforts on labor reform. To the extent that the RRM improves political support for open trade between the two countries, the process and the expenditures share some similarities with policies of trade facilitation.

Section 5 presents some stylized facts on the RRM during its first three years. The RRM started slowly, with the US government investigating situations at just ten different facilities in Mexico during this period. Unsurprisingly, most of these investigations were of the automotive sector. Nevertheless, there were some interesting and important differences across the situations.

The last two sections look to the future. Section 6 turns to the political–economic literature on trade agreements and issue linkages and proposes additional research needed to understand the implications of the RRM, including the need to assess its impact on workers and Mexican suppliers at facilities affected and those unaffected by RRM situations. Section 7 draws on lessons learned so far and examines the potential for transposing facility-specific RRM-like structures for labor or other areas, such as the environment, into future economic agreements.

2. US Origins of the Rapid Response Labor Mechanism

Reaching agreement on the RRM required a perfect storm of political–economic events in the United States. These events included the election of Donald Trump in 2016; the unique way and position through which the Trump administration was able to renegotiate the NAFTA, including its timing with respect to the election calendars in both Mexico and the United States; and the way Democrats in the US Congress renegotiated the USMCA after Trump's deal arrived at their door.

2.1 Candidate Trump and the Anti-NAFTA Campaign

Candidate Donald Trump demonized Mexico during the 2016 presidential campaign. His nativist approach began the day he kicked off his bid, in June 2015, with ‘They're bringing drugs. They're bringing crime. They're rapists.’Footnote 1 His approach stoked fear over migrants crossing the southern border. He pledged to build a wall to stop them, which, he assured voters, Mexico would pay for, and he promised a massive new deportation program.

During the 2016 campaign, Trump also ran against trade with Mexico and against the NAFTA, which he called the ‘worst trade deal ever’.Footnote 2 He targeted American automakers. In April 2016, when Ford announced it was building a new assembly plant for small cars in Mexico, Trump stated that this ‘is an absolute disgrace’ and predicted that such investments in Mexico by American companies would continue ‘until we can renegotiate NAFTA to create a fair deal for American workers’.Footnote 3

Trump best played on American fears about the NAFTA when Carrier, a US-headquartered company that produced air conditioners and furnaces, announced plans in February 2016 to close a unionized plant in Indiana and open a new factory in Mexico. Trump made the company a pariah. He inserted Carrier into his stump speech, naming and shaming and threatening the company on the campaign trail for months. If elected, Trump promised, ‘I will call the head of Carrier and I will say, “I hope you enjoy your new building. I hope you enjoy Mexico. Here's the story, folks: Every single air conditioning unit that you build and send across our border – you're going to pay a 35% tax on that unit.”’Footnote 4

Trump exploited the narrative through the election, waiting until after 8 November to cut a deal. The chief executive of United Technologies (Carrier's parent), Trump, and his vice president-elect, then-Indiana governor Mike Pence, worked out a face-saving arrangement through which, in exchange for $7 million of state subsidies, Carrier would keep the Indiana plant open but still lay off half of the facility's 1,350 workers.Footnote 5 When Trump oversold the benefits of the deal publicly, the president of the local union representing Carrier workers called him out. Trump retaliated on Twitter with ‘Chuck Jones, who is President of United Steelworkers 1999, has done a terrible job representing workers. No wonder companies flee the country!’Footnote 6

2.2 The NAFTA on the Chopping Block to Fix the Trade Deficit

As promised during his campaign, on Trump's first Monday as president, he pulled the United States out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) Agreement – an agreement the Obama administration had signed with Mexico and ten other countries in February 2016 but that had been stuck in limbo, with Congressional leaders refusing to put it to a vote.

Trump's approach to US trade policy, including toward Mexico, would be nontraditional and confrontational. His administration announced its intention to renegotiate the NAFTA in May 2017, releasing a set of negotiating objectives in July.

Trump's negotiations began from a place of disappointment and grievance. The preamble of the negotiating objectives document stated:Footnote 7 ‘Since the deal came into force in 1994, trade deficits have exploded, thousands of factories have closed, and millions of Americans have found themselves stranded, no longer able to utilize the skills for which they had been trained … . In June 2016, then-candidate Donald J. Trump made a promise to the American people: He would renegotiate NAFTA or take us out of the agreement.’

Trump was not interested in achieving a mutually beneficial outcome for the United States, Canada, and Mexico. To Trump, trade was a zero-sum game. His goal was not the traditional one of reducing trade barriers, increasing economic efficiency, and growing a larger economic pie for the three countries to share. His intent was to shift a larger share of the pie toward the United States, even if the size of the pie shrunk.

Such an approach in trade negotiations has historically been difficult to pull off. When the negotiating starting point already had high trade barriers, unconstrained by an agreement, raising them further was often an idle threat. Put differently, countries could always choose not to participate in a trading partner's proposed deal if they would not gain from it.

That was not the starting point with the NAFTA in 2017. The three countries began with policies of nearly free trade toward each other and considerable asymmetry in the sizes of their economies and their resulting trade dependencies. The implication was that Trump could make the Mexican and Canadian economies worse off by raising trade barriers in ways that would hurt the United States but by less than it would hurt its partners. He often threatened to do so by ripping up the NAFTA, including in the negotiations objective preamble.Footnote 8 He also did so through specific trade policy actions described in more detail below.

In August 2017, the three countries began negotiating, aiming to reach a new deal by December. By October, after four rounds of talks, it had become clear that the governments were not on the same page, and negotiations were halted. Trump's US Trade Representative (USTR), Robert Lighthizer, said ‘Frankly, I am surprised and disappointed … . We have seen no indication that our partners are willing to make any changes that will result in a rebalancing and a reduction in these huge trade deficits.’Footnote 9

2.3 Autos at the Center of Trump's Trade Deficit Policy

The Trump administration's overarching trade policy goal was to reduce America's trade deficit. Mexico had the second-largest bilateral trade surplus with the United States,Footnote 10 and to Trump, the fault rested with the auto sector. In 2016, Mexico exported $293.5 billion of goods to the United States and imported only $230.2 billion, a $63.3 billion difference. For autos, US imports from Mexico were $64 billion larger than US exports, leading Trump's Commerce Secretary, Wilbur Ross, to argue in a Washington Post op-ed that ‘the United States would enjoy a trade surplus with its NAFTA partners were it not for the trade deficit in autos and auto parts’.Footnote 11

Trump's objective was political, as there is no well-accepted economic reason for policymakers to focus on bilateral trade balances overall, let alone balanced trade within a sector. Moreover, Trump was looking only at the bilateral trade deficit defined in terms of gross trade flows which do not account for the fact that, for example, an American-made auto part may cross a border multiple times before being embedded in the final vehicle assembled in Mexico being exported back to the United States. When the US trade deficit with Mexico was measured in value-added terms – taking into consideration the fact that much of the final value of a good imported from Mexico was US content embedded in that export – the bilateral deficit was considerably smaller (Johnson and Noguera, Reference Johnson and Noguera2012). Furthermore, Mexican customs data showed that the share of US content in imported Mexican manufactures was 30% – much larger than Ross's estimate of 18% (de Gortari, Reference de Gortari2017).

The Trump administration was channeling a narrative of decline within the massive, multi-decade transformation of the American automobile industry, including during the NAFTA period, even though the beginnings of that transformation predated the NAFTA by years. The challenges facing America's unionized autoworkers also reflected economic shifts taking place within the United States. In the 1950s and 1960s, America's Big Three automakers – Ford, General Motors (GM), and ChryslerFootnote 12 – were at the center of the world's new automobile industry, making cars for the growing middle class, with the United Auto Workers (UAW) union at its core.

Many changes took place in the following decades – and much of the change was painful for American automakers and the UAW. The European and Japanese manufacturing economies had recovered quickly from the devastation of World War II, creating successful auto industries of their own. In the 1970s, OPEC weaponized oil supplies, causing US gasoline prices to spike and long lines to form at gas stations. US automakers – which had mainly developed large gas guzzlers – were caught flatfooted in the face of a large shift in American consumer demand. The result was a surge of imports from Japan of smaller, fuel-efficient, and less expensive cars. Chrysler nearly went bankrupt in 1979 and required a federal bailout.

In 1981, the United States demanded that Japanese automakers voluntarily restrain their export penetration into the US market. Those voluntary export restraints only accelerated the decision by Japanese automakers to build plants in the United States to produce locally for American consumers. With those plants, Japanese car companies such as Honda, Toyota, and Nissan created tens of thousands of American jobs. The first plant, churning out Honda Accords, was located not far from Detroit, in Marysville, Ohio. But most of the new plants from Japanese and then European automakers were located in southern states: Tennessee, Kentucky, Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina – the right-to-work states in which most of the new workers were not unionized, to the frustration of the UAW.Footnote 13 Much of this new local competition for the Big Three and their unionized workforces thus pre-dated the NAFTA, which came into force in 1995.

Total vehicle production at US plants actually increased by 2.4 million units between 1990 and 2016 – roughly the NAFTA period – but that growth often arose far away from Detroit.Footnote 14 Over time, assembly plants and many of the auto parts suppliers in the United States became clustered around a North–South corridor referred to as ‘auto alley’, defined as the area within 100 miles of US interstate highways I-65 and I-75 (Klier and Rubenstein, Reference Klier and Rubenstein2008). In part, the alley emerged to accommodate just-in-time suppliers shipping parts to multiple plants (often run by different automakers) and to minimize the cost of transporting finished vehicles to American consumers.

At the same time, the North American automotive supply chain deepened into Mexico. By 2016, Mexico was making 19.5% of all light vehicles assembled in North America, up from 6.5% in 1990. Mexican production thus accounted for about half of the 5.5 million unit increase in light vehicles produced in North America over this period.

These plants and their supply chains were doing more than simply assembling cars for sale into the United States. By 2016, Mexico had signed trade agreements with 16 countries that gave it potentially tariff-free access to 47% of the global new vehicle market and likewise gave those countries duty-free access to the Mexican market (Swiecki and Maranger Menk, Reference Swiecki and Maranger Menk2016). From the US perspective, one fear was that Mexico's reduction in trade barriers toward the rest of the world meant that parts that did not originate in North America – especially parts imported into Mexico from China, which had a growing auto sector of its own – would find their way into vehicles being assembled in Mexico for sale in the United States, further squeezing out American parts suppliers.

The automotive sector was thus important economically and politically to both countries at the time of the NAFTA renegotiations. Combining assembly and parts, autos made up a disproportionately large share (26%) of Mexico's manufacturing exports to the world, even though they accounted for just 3.5% of Mexico's GDP.Footnote 15 Roughly 830,000 people worked in Mexico's automotive sector, about 2% of Mexico's total employment in 2016.Footnote 16 By comparison, the United States employed 806,000 workers in the sector. Although they represented only 1% of the American workforce, autoworkers held roughly 7% of US manufacturing jobs, and policymakers had worried about declining US manufacturing employment for decades.Footnote 17

Comparative advantage was responsible for some of the fragmentation of the automotive supply chain and its geographic reallocation of segments into Mexico. For example, wage costs were significantly lower in Mexico. Estimates available at the time of the NAFTA renegotiation suggested that Mexican wages in assembly averaged about one fifth of US levels, whereas Mexican wages in auto parts manufacturing were only about one-eighth as high, with the resulting difference in labor costs averaging $674 per car (Swiecki and Maranger Menk, Reference Swiecki and Maranger Menk2016). Some of those labor cost differences reflected not productivity differences but differences in worker rights and collective bargaining power that trace back to concerns with Mexico's labor laws and their enforcement, as detailed below.

2.4 Getting to ‘Yes’ on the USMCA

At the time of the renegotiations, automakers were fairly content with the NAFTA; they organized politically to try to fight the Trump administration's proposals.Footnote 18 The industry argued that Trump's proposed new rules would raise their costs – and hence prices for American consumers – and make the North American industry less competitive globally.

The original US proposals for renegotiating the NAFTA were extreme. For autos, the Trump administration reportedly wanted to raise the regional content requirement from 62.5% to 85%.Footnote 19 Stressing America first, Trump also wanted an unprecedented US-specific content requirement of 50%. The administration also proposed a five-year sunset clause for the agreement, which would reduce certainty for firms investing in Mexico regarding their future duty-free access to the US market.

US trading partners were troubled by these early proposals. Canada's foreign minister and chief negotiator, Chrystia Freeland, called Trump's requests ‘unconventional’, indicating that they would ‘turn back the clock on 23 years of predictability’.Footnote 20

In the following months, the Trump administration turned to credible threats that the alternative for Canada and Mexico was something worse and to actions that would punish their economies in ways that went beyond the threatened withdrawal from the NAFTA (Table 1 shows the chronology of events). In June 2018, Trump imposed tariffs on steel and aluminum from Canada and Mexico. (From March to May of 2018, Canada and Mexico had been given a chance to negotiate a quick resolution to the NAFTA on Trump's terms, but they did not accept.Footnote 21) The move was costly for Canada, Mexico, and the United States, both economically and politically. The American aluminum industry association came out against the tariffs, as the sector was highly integrated across North America, with primary aluminum smelted in Canada sent downstream to US factories to make refined aluminum products.Footnote 22 The United Steel Workers (USW) union argued against imposing steel tariffs on Canada because the union represented workers at plants in both countries.Footnote 23

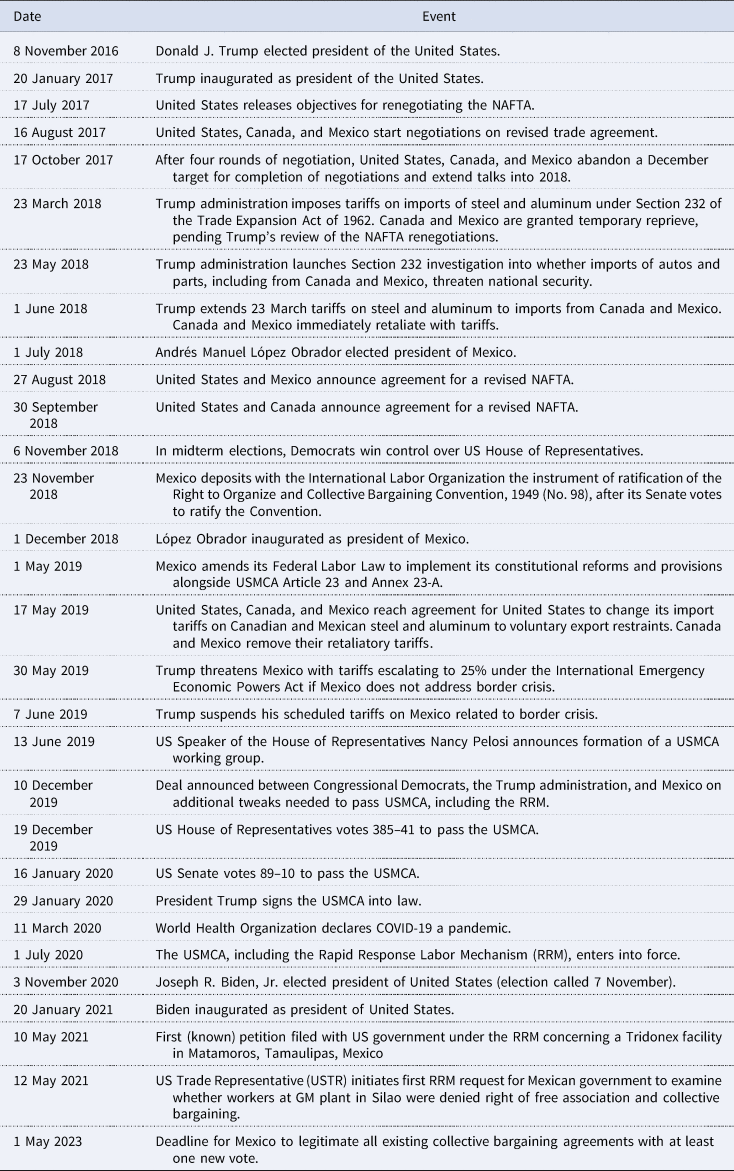

Table 1. Timeline of the US–Mexico–Canada agreement, the rapid response labor mechanism, and Mexico's labor reform agenda

The Trump administration then turned to automobiles. In late May 2018, the Commerce Department began an investigation that threatened tariffs on autos and auto parts. The self-inflicted harm of the steel and aluminum tariffs showed partners that Trump was serious about redistributing the economic pie toward the United States, even if it meant shrinking it for everyone. US tariffs on automobiles were a much bigger economic threat. Canadian and Mexican exports of steel and aluminum to the United States were only about $15 billion annually. Their combined exports to the US of automobiles and parts were over ten times that, at $160 billion.Footnote 24

These economic threats arrived on Mexico's doorstep at the moment of a national election. On 1 July 2018, Andrés Manuel López Obrador was elected president, with 53% of the popular vote. It soon became clear that he wanted an agreement in place on a new NAFTA before taking office on 1 December. Legal calendars surrounding the approval of the deal in the US Congress meant the deadline for its conclusion had to be the end of August. The United States and Mexico pushed Canada to the side and began negotiating bilaterally, thus reaching agreement in August. With the new bilateral deal with Mexico within reach, Trump once again threatened to terminate the NAFTA and implement a tariff on auto imports from Canada.Footnote 25 One month later, Canada signed as well.

The USMCA that was sent to Congress differed from the NAFTA in several important ways. As Trump wanted, it included more restrictive rules of origin for the automotive sector. Although the initial US proposals were scrapped, the regional content provisions increased from 62.5 to 75%. Furthermore, at least 40% of the value of North American content had to be manufactured with wages of $16 an hour or more. This requirement likely ensured that more content was from the United States (or Canada), as wages in Mexico were much lower. Next, more expansive binding state-to-state dispute settlement provisions for labor and environment were added. Finally, Article 32.10 allowed any country to terminate the agreement if either of the other partners signed a free trade agreement with a non-market economy (i.e., China).

Trump's threat of tariffs on Mexican and Canadian autos was sufficiently credible that both countries also negotiated side letters – getting the administration to allow a certain import volume annually before the tariffs would kick in – in the event that the United States followed through with the auto tariffs that remained under threat.

Such was the initial 2018 agreement that Trump sent to Congress. But House Democrats had made clear that Trump's USMCA was insufficient. Rep. Sander Levin (D-MI), former Chair of the House Ways and Means Committee, said that the labor provisions in the deal would garner little if any Democratic support for votes in the House.Footnote 26 Democrats wanted more, in part because of discontent over the perceived failure of labor provisions and enforcement mechanisms in US free trade agreements preceding the USMCA.

The original NAFTA renegotiations had begun within months of a final decision by the only arbitral panel constituted under a US trade agreement to address labor matters. The United States lost the case, which it had brought over Guatemala's failure to effectively enforce its labor laws in a process that had begun more than a decade earlier (Claussen, Reference Claussen2020). This protracted enforcement exercise prompted the emphasis on rapid response in the development of a new tool to combat labor violations.

2.5 How House Democrats Added the RRM

In November 2018, the Democrats won back control of the House of Representatives. The Trump administration would need to engage in bipartisanship to approve the USMCA. It took over a year before Congress finally agreed to do so.

Before the House would take up the USMCA, the Republican-controlled Senate had to work through its main objections. Senator Chuck Grassley (R-IA) indicated that the Senate would not consider passing the USMCA until Canada and Mexico removed their retaliatory tariffs on American agriculture exports. Canada and Mexico said that they would not do so unless Trump removed his steel and aluminum tariffs on their exports. Only in May 2019 did the United States, Canada, and Mexico agree to remove those tariffs so that the deal could push ahead.Footnote 27

In mid-June, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi set up a USMCA working group with eight Democrats under Ways and Means Chairman Richard Neal (D-MA) to address four main issues: labor, the environment, enforcement, and drug pricing.Footnote 28 (Katherine Tai, who would become the US Trade Representative under the Biden administration, was Chief Trade Counsel on the Ways and Means Committee.)

On 10 December 2019, Congressional Democrats announced a deal on a set of amendments to the 2018 version of the agreement that would secure enough support to approve the USMCA.Footnote 29 The most substantive change was the creation of the RRM. It was important politically because it caused significant groups of organized labor to support a US trade agreement for the first time.Footnote 30 AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka, stated ‘I am grateful to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and her allies on the USMCA working group, along with Senate champions like Sherrod Brown and Ron Wyden, for standing strong with us throughout this process as we demanded a truly enforceable agreement.’Footnote 31

The UAW was more circumspect. It neither rejected nor endorsed the deal, emphasizing the need for enforcement. ‘USMCA will not bring back the hundreds of thousands of good US manufacturing jobs that have already been shipped to Mexico’, it noted. ‘We will be watching. We will be aggressive in pushing for enforcement of provisions. And we are under no illusion that this revised agreement alone will restore America's middle-class manufacturing base.’Footnote 32

The USMCA Implementation Act passed with overwhelming bipartisan majorities in both the House (385–41) on 19 December 2019, and the Senate (89–10) on 16 January 2020. On 29 January 2020, President Trump signed it into law; on 1 July 2020, the agreement came into force.

3. The Rapid Response Labor Mechanism from the Perspective of the Mexican Labor Reform Movement

For Mexico, getting the RRM required its own perfect storm of political–economic events. One was the timing of the Mexican presidential transition. Another was the decision to focus on the lack of democratically elected unions as a major source of the problem holding back Mexican workers, who had long suffered from low wages, long hours, and hazardous working conditions (OECD, 2019). Their economic livelihoods had failed to significantly improve despite the opportunities presented by Mexico opening up to the global economy when it joined the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1986 and integrating supply chains with the United States and Canada more closely under the NAFTA.

To some observers, the longstanding structural problem – which would become the RRM's main target – was Mexico's ‘protection contracts’. Mexico had a long history of collusion against worker rights. Labor advocates argued that ‘since the 1940s, government officials, employers, and the ‘official’ unions have colluded to prevent strikes, keep down wages, and to fire workers who stood up for their rights all for the purpose of encouraging foreign investment’ (Alexander and LaBotz, Reference Alexander and LaBotz2014, 49). Areas of Mexico were dominated by corporatist or state-controlled unions, such as the Confederation of Mexican Workers (CTM).

Some labor scholars saw the Mexican government as complicit in allowing sham unions to masquerade as representing workers and to sign collective bargaining agreements that were unfavorable to their workers’ own interests. These ‘protection unions’ would negotiate ghost contracts with firms without the participation of the workers they were supposed to represent (Department of Labor, 2019; Santos, Reference Santos2019b). The underlying problem was well documented, including by the International Labor Organization (ILO) and the US government.Footnote 33

Under outside pressure, the Mexican government had promised to undertake labor reforms on numerous occasions, especially during the US-led negotiations of the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP). However, when the Trump administration pulled the United States out of the TPP, domestic progress on labor reform in Mexico once again stalled (Santos, Reference Santos, Kingsbury, Malone, Mertenskötter, Stewart, Streinz and Sunami2019a; LeClercq and Curtis, Reference LeClercq, Curtis, Huerta-Goldman and Gantz2021).

In 2017, Mexico adopted a constitutional reform intended to transform its labor justice system. In 2018, it ratified the ILO Convention on the Right to Organize and Collective Bargaining. As required by the USMCA (November 2018 version), in May 2019 Mexico enacted amendments to its Federal Labor Law to implement its constitutional reforms of 2017. The overhaul included changes to its domestic institutions for registering unions and resolving labor disputes. The Mexican government also appropriated over $70 million to implement the new labor courts, inspectors, and other administrative bodies that would form its new labor justice administration (Department of Labor, 2019).

With the Federal Labor Law, and as required by the USMCA, Mexico established a four-year transition that set 1 May 2023 as the deadline for full implementation of its reforms. Full implementation could have meant that all of Mexico's estimated 139,000 existing collective bargaining agreements would need to be voted on by workers at least once by that date, which in some instances would require voting out an existing protection union, voting in a new union, and having the employer and the Mexican government recognize the new union.Footnote 34 Throughout this period, some saw the RRM as a way to use external enforcement – e.g., naming and shaming firms, backed by US trade sanctions – to complement the Mexican government's own reform efforts to empower workers to navigate this new system.

4. Explaining the Rapid Response Mechanism

The RRM is a facility-specific mechanism that seeks to address violations of freedom of association laws and rights. If, for example, the US government believes that workers at a facility in Mexico are being denied the right to bargain collectively, it can take punitive action against the facility (Claussen, Reference Claussen2019). The belief must relate to a ‘covered facility’ – a plant producing for export or that competes with exports in a ‘priority sector’, defined as one that produces manufactured goods, supplies services, or involves mining.

The typical situation to emerge is a denial of rights at a plant in Mexico initiated by the US government under the bilateral US–Mexico RRM (there is also a Canada–Mexico RRM).Footnote 35 Although it is reciprocal in its commitments, facilities in the United States and Canada are largely shielded from Mexico's review, as a result of a limiting condition on the eligibility of those facilities for consideration in the agreement text.Footnote 36

4.1 How the RRM Can Work

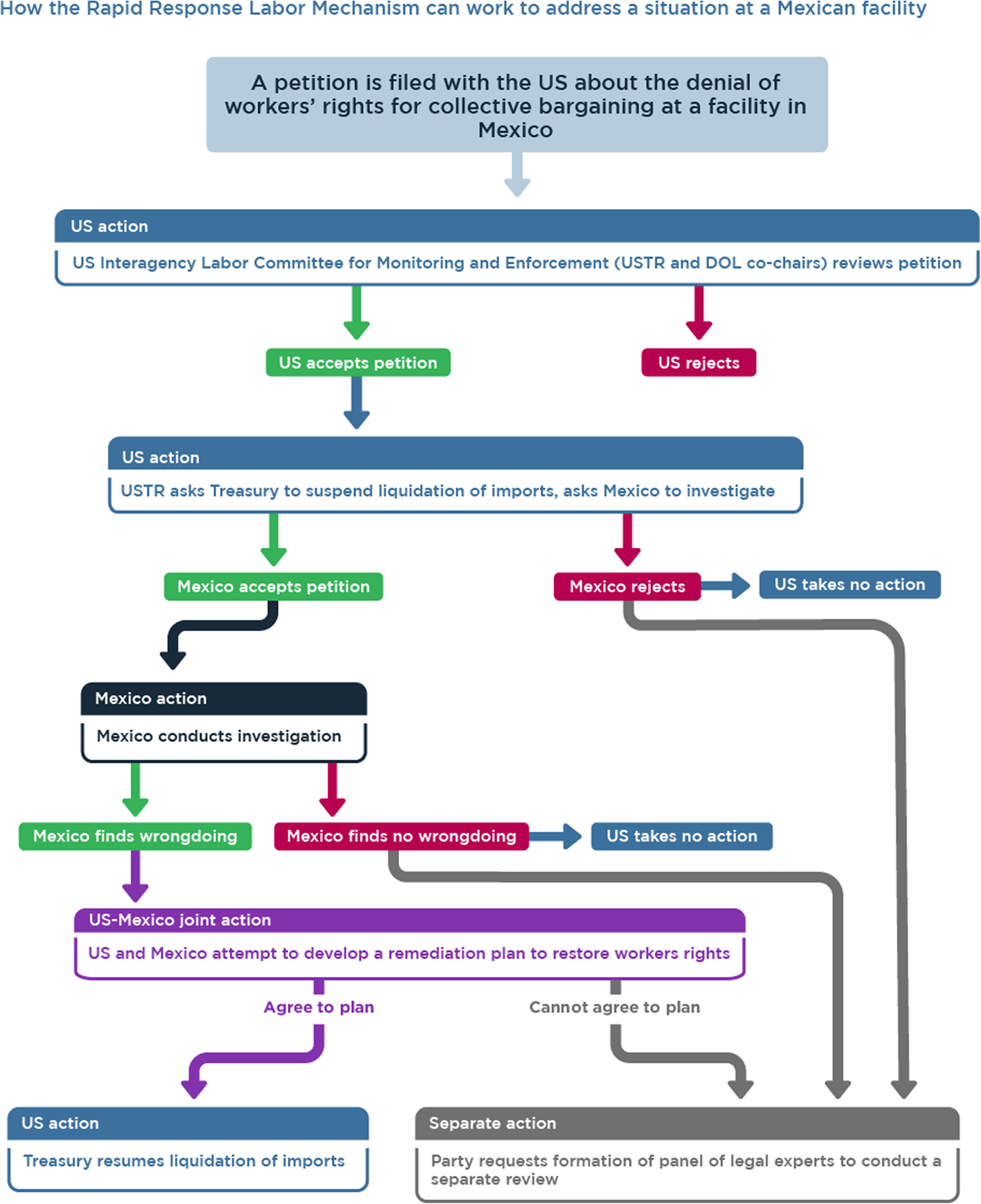

Under the RRM, any individual, group, or government can file a petition with the US government; the US government can also initiate an investigation into potential situations at a facility in Mexico on its own. An anonymous web form and phone hotline allow individuals to report rights violations, while remaining shielded from retribution. Figure 1 shows how the RRM can work.

Figure 1. The US–Mexico–Canada Agreement implements a strict review process meant to improve workers' rights in Mexico

Note: USMCA = US–Mexico–Canada Agreement; RRM = Rapid Response Labor Mechanism

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Within the US government, a petition is reviewed by the newly established Interagency Labor Committee for Monitoring and Enforcement, co-chaired by the USTR and the Secretary of Labor. If the committee finds sufficient evidence of a denial of rights, it can accept the petition and ask Mexico to review the matter. Upon delivering such a request to Mexico, the USTR may ask the US Secretary of Treasury – the chief tax collection official in the United States – to suspend liquidation of import duties on goods from that facility until the issue is resolved. This move has the effect of putting in limbo the tax bill for all transactions between the Mexican facility and US importers of its merchandise.

If Mexico agrees that a denial of rights took place or is ongoing, the United States and Mexico may pursue a ‘course of remediation’, designed to rectify the violation of rights. The text of the agreement does not offer specific content for the course, but agreements have included requirements to hold a new union vote and for external observers to monitor the election. Where no course of remediation is concluded or successful, the United States can impose penalties on the company until the problem is fixed. Where the United States and Mexico disagree, either party is entitled to convene a panel of labor experts to review the matter and make a factual determination about any denial of rights.

4.2 US Government Support for the RRM and Mexico's Labor Reform

The RRM requires significant financial resources.Footnote 37 The US Congress appropriated $30 million over 2020–2027 to ‘monitor compliance with labor obligations’, including by allocating funding to support full-time employees from the US Department of Labor's Bureau of International Labor Affairs (ILAB) to staff the committee.Footnote 38 The Department of Labor sent five full-time employees to the US Embassy and consulates in Mexico to help monitor and support RRM actions and to report back to Congress quarterly. Appropriations also supported the hiring of several additional attorneys and labor-focused staff at the USTR, as well as the USTR official detailed to the US Embassy in Mexico City.

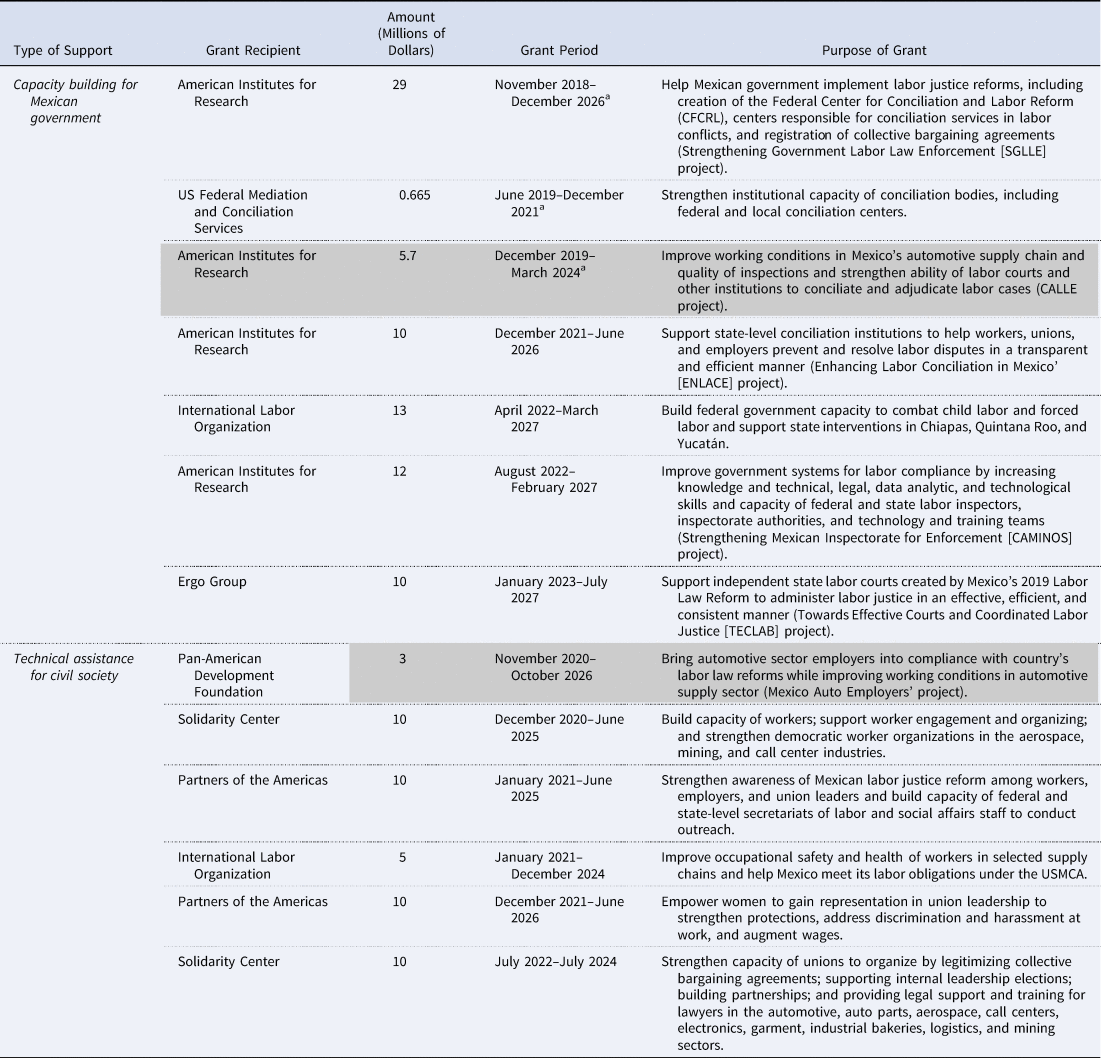

Congress also appropriated funding for technical assistance and capacity building within Mexico, including $180 million for ILAB to support Mexico's labor reforms made available in 2020–2023 (Table 2). ILAB has since directed some of the capacity building to help the Mexican government create new institutions to register legitimate unions and their collective bargaining agreements, conduct inspections of plants and workplace facilities, and support fair adjudication between firms and workers over the latter's rights. It has funded efforts to digitize all collective bargaining agreements and union registration documents, train labor officials, and develop a career civil service structure (IMLEB, 2021).

Table 2. Examples of capacity building and technical assistance by the Department of Labor's International Labor Affairs Bureau in support of Mexico's labor reforms under the USMCA

Capacity building has also meant working on the ground to provide information to Mexican workers about their rights. Under the Mexican labor reforms, workers had the ability, if they could organize quickly, to vote out the old protection union and vote in a new union that might better represent their interests. Much as trade facilitation can help firms learn about latent foreign demand for their products, this funding could empower Mexican workers by providing information about their rights under the new law and how to exercise them through Mexico's new institutions. (Doing so could facilitate the continuation of trade if improved Mexican worker rights made it politically easier for US government officials to keep the US import market open to goods produced at their place of work.) Toward this end, ILAB provided grants of roughly $50 million to various NGOs to raise awareness of the new labor systems among workers, employers, and union leaders.

Much of the early funding for capacity building and technical assistance focused on workers in Mexico's automotive supply chain, with potential implications for early use of the RRM itself. In November 2020, ILAB made a $3 million grant to the Pan-American Development Foundation for a Mexico Auto Employers’ Project. Another $5.7 million grant was allocated to the American Institutes for Research for the Compliance in Auto Parts through the Labor Law Enforcement (CALLE) project, which seeks ‘to improve working conditions in the Mexican automotive parts sector by improving government enforcement of labor laws’ (Department of Labor, 2020).

5. Early Use of the Rapid Response Labor Mechanism

The USMCA entered into force on 1 July 2020. Some observers expected an immediate surge in RRM filings. In early September 2020, AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka indicated plans to submit petitions for consideration that month.Footnote 39 Yet, the first (publicly known) petition did not arrive until the following spring.

5.1 Some Delay before the RRM is Used

There are a number of reasons why the RRM situations were slow to materialize. First, the COVID-19 pandemic led to lockdowns, social distancing, and supply chain disruptions, including for the North American automobile industry. Many facilities remained idle throughout 2020.Footnote 40 Second, organized labor in the United States was busy campaigning against President Trump and on behalf of candidate Joe Biden during 2020; it was unlikely to want to give Trump any political wins that might help his reelection chances.Footnote 41 Third, disseminating information about the tool and educating stakeholders about how to use it took time. Fourth, given the political spotlight on the RRM, early uses would likely need to have a high probability of success.

By the late spring of 2021, conditions were ripe for the RRM. The Biden administration had fully staffed the principal positions overseeing the RRM. Appointees were well versed in the details of the mechanism; several, including Katherine Tai, President Biden's choice for USTR, had helped write its text.Footnote 42 At the Department of Labor, the administration chose Thea Lee to head ILAB, the other key partner in the US interagency process on the RRM, as Deputy Undersecretary for International Affairs.Footnote 43 The first invocations of the RRM emerged in May 2021, as these appointees took up their new roles.

5.2 US RRM Situations Brought to Mexico's Attention over the USMCA's First Three Years

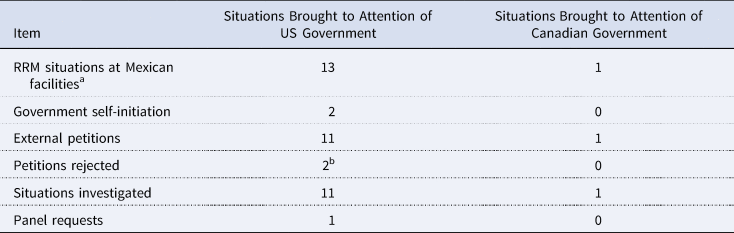

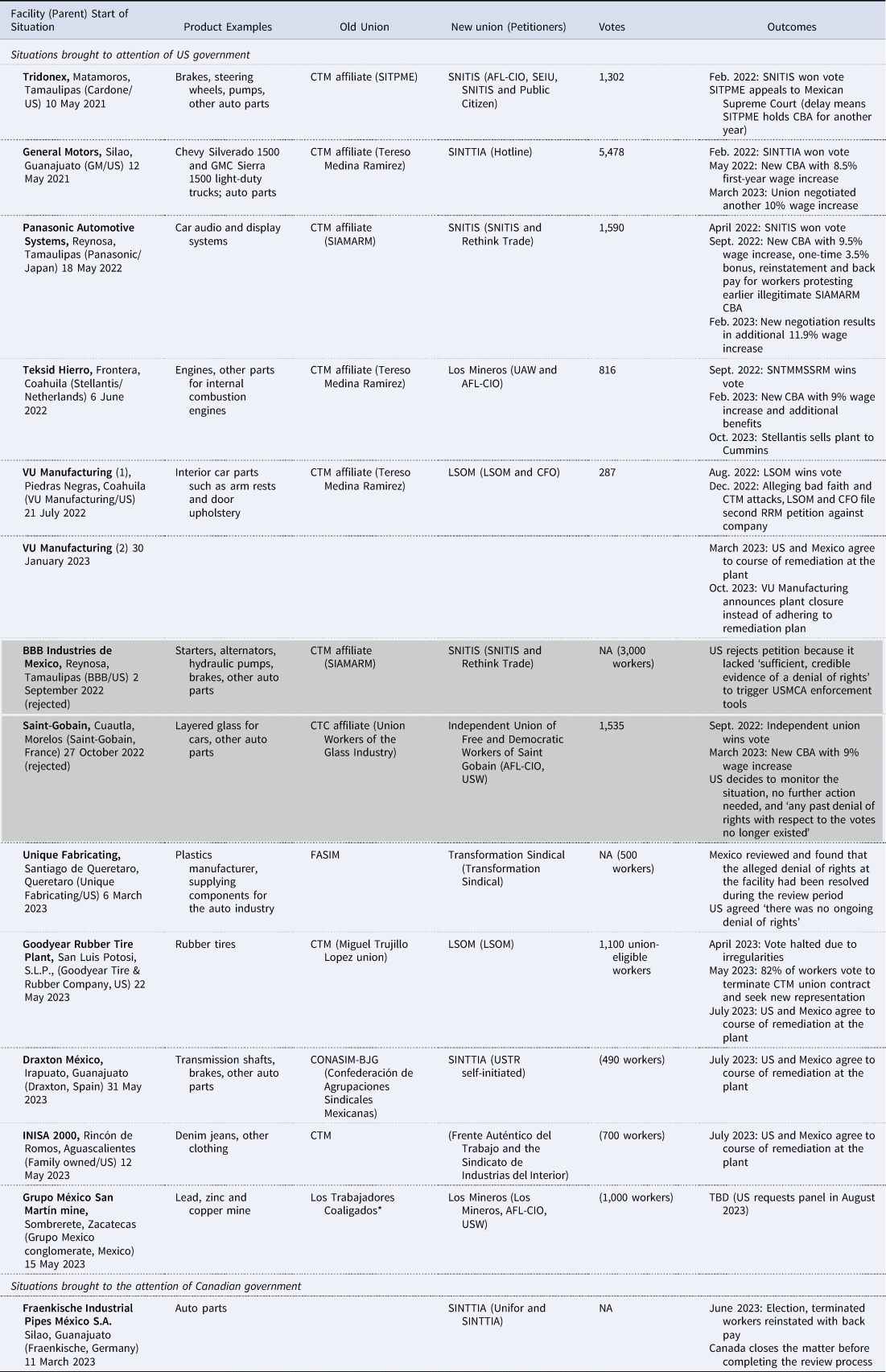

The USTR accepted nine petitions and self-initiated two others, seeking Mexico's review on 11 occasions in the first three years of the RRM (Table 3). These situations cumulatively only covered an estimated 16,500 Mexican workers. Some details are known of two other petitions that the USTR rejected during the period. Canada received and pursued one petition under its bilateral RRM with Mexico. (The full set of petitions that USTR and/or Canada rejected is not publicly known.)

Table 3. Number of Mexican Rapid Response Labor Mechanism situations brought to attention of US and Canadian governments between July 2020 and June 2023

Notes: aFacilities facing multiple situations (e.g., VU Manufacturing) are counted as separate facilities.

b Additional rejected petitions likely exist, but public data concerning the facilities targeted in those petitions are not yet available.

Sources: Information for ongoing situations as of 10 October 2023. Constructed by authors from media reports, petitions, USTR website, Canadian government website, and IMLEB (2023).

In some ways, the US RRM situations with Mexico were all very similar. Most attacked the same problem: a fight at a Mexican plant between two sets of workers. Typically, one set was attempting to oust an old union and then establish itself as the new union (i.e., exactly the concern identified in Section 3).Footnote 44 Many of the old unions were affiliates of CTM.Footnote 45 The first nine situations targeted facilities in the automobile supply chain, as did the sole situation raised by Canada.Footnote 46

Although the process to resolve each situation was unique, in the majority of situations the old union was thrown out and a new union was installed and legitimated. In some situations, the new union bargained collectively to achieve a wage increase that was greater than the rate of inflation. The governments also sometimes worked to resolve unfair situations facing workers who may have lost their jobs or otherwise been mistreated through restoration of employment and payment of back wages. In one situation, the company chose to shut down the Mexican plant rather than comply with US and Mexican government demands.Footnote 47

There were also some important differences across the 11 situations the US government pursued in Mexico (Table 4). One of the very first invocations of the RRM was against a plant belonging to the Mexican subsidiary of GM. The plant was in the city of Silao, in the state of Guanajuato, in the middle of Mexico (Figure 2). Workers at the plant assembled name-brand Chevy Silverado and GMC Sierra trucks, among other vehicles. The most favored nation (MFN) tariff on these trucks was 25%; suspending liquidation could thus potentially have left GM with a sizable tariff bill to pay if the situation were not resolved. The Silao plant was also large; reportedly, over 5,000 workers eventually voted in the union election.Footnote 48 The outcome of the RRM situation with GM was also relatively successful from the perspective of the workers seeking new representation: After winning the vote, the new union negotiated a collective bargaining agreement in May 2022 that included an 8.5% wage increase the first year. Less than a year later, it negotiated another 10% wage increase. (The inflation rate in Mexico was 7.4% in 2021 and 7.8% in 2022.)

Table 4. Descriptions of Rapid Response Labor Mechanism situations brought under the US–Mexico–Canada Agreement between July 2020 and June 2023

Notes: NA = Not available, TBD = To be determined.

*Not a protection union, but during a strike by the petitioning union, ‘a labor organization not lawfully authorized to represent workers for the purposes of collective bargaining’.

Shaded potential situations are those in which USTR rejected the petition. Additional rejected petitions likely exist, but public data concerning the facilities targeted in those petitions are not yet available.

Source: Information for ongoing situations as of 10 October 2023. Constructed by authors from media reports, petitions, USTR website, Canadian government website, and IMLEB (2023). Products identified from company and state (not facility) level data shared by S&P Global Market Intelligence for 2022.

Figure 2. Most US Rapid Response Labor Mechanism situations have targeted Mexico's automobile supply chain

Note: With the exception of INISA 2000 (textiles) and Grupo México (mining), all facilities are in the automobile sector.

Source: Compiled by the authors, map data © OpenStreetMap.

That one of the first RRM situations was so high profile likely put on notice all of the other automakers with assembly facilities and supply chains in Mexico. However, the next RRM situation was very different. It was also more typical of other situations that were about to emerge.

Just before the USTR activated the RRM at GM, labor groups filed a petition involving Tridonex, a subsidiary of Cardone, a Philadelphia-based auto parts company. The Tridonex facility was located on the Mexican border with Texas, two states away from the GM plant (see Figure 2). This plant manufactured auto parts such as steering wheels and brakes. Behind the petition were two American unions (the AFL-CIO and the SEIU); a Washington, DC think tank (Public Citizen); and the new Mexican union (SNITIS) struggling to be recognized by the facility and seeking to do so under Mexico's new labor law.

On procedural grounds, the case of Tridonex was different for other reasons. The Mexican government refused to accept the US review request, arguing that the problematic events at the facility occurred before the USMCA entered into force. Not to be deterred, the USTR reached out to Cardone and entered into an agreement directly with the company.Footnote 49 Although Tridonex eventually recognized SNITIS as the new union, the protection union managed to delay that outcome by over a year, including through appeals to the Mexican Supreme Court.Footnote 50

As with GM and Tridonex, all but two of the RRM situations to emerge involved Mexican subsidiaries of foreign-headquartered companies.Footnote 51 Several reasons may explain why few Mexican-headquartered firms were targeted. The early caseload inevitably reflected the interests of American unions and policymakers, as the capacity building to educate Mexican workers to generate locally motivated petitions would require time to take effect. Workers at subsidiaries of foreign-headquartered companies may also be better informed about their potential rights than workers at Mexican-headquartered companies, thanks to access to information from union activity in other countries that travels through worker networks within the multinational. It also could be that US officials intend to target firms that export to or have brand recognition in the United States.

Somewhat puzzling is the fact that many of the Mexican subsidiaries subject to RRM situations were relatively unknown. Aside from GM, in only three other instances (Panasonic, Stellantis, and Goodyear) was the foreign parent close enough to a household name that it had a sufficient public reputation and brand recognition that could be tarnished by bad press and the threat of consumer boycotts in the United States. While both the GM and Tridonex labor situations were covered by the New York Times,Footnote 52 in part due to their novelty, the others have yet to receive significant media coverage in the United States.Footnote 53

Some of the situations involved Mexican facilities with potentially very small direct exports to the United States. (Data are not available on domestic transactions between Mexican facilities.) Nevertheless, a targeted Mexican facility might be economically sizable through its sales to another Mexican plant of hundreds of millions of dollars of parts (e.g., steering wheels or tires) for assembly by that second plant into, say, final vehicles for export to the United States. An open (legal) question is whether the US government would attempt to sanction inputs embedded by the second plant if the threat of suspension of liquidation of direct US imports was not a big enough penalty to induce compliance at the first facility. Nevertheless, some of the facilities were likely relatively small – e.g., available evidence suggests the VU Manufacturing, Unique Fabricating, and Draxton situations involved fewer than 500 workers.

In terms of the unions, SNITIS and SINTTIA were the new unions attempting to oust the old union in three petitions each, often with the support of American unions or Washington, DC think tanks. (The AFL-CIO was involved in four petitions, the USW in two, and SEIU and UAW in one each; Public Citizen and Rethink Trade were involved in three of the petitions.Footnote 54) On the ground in Mexico, labor activists like Susana Prieto Terrazas actively worked across multiple situations as well.Footnote 55

Use of this tool – which led to the transition from one union to another – was often accompanied by improprieties. In the Tridonex situation, ‘thugs [were] hired by the incumbent union around the plant to intimidate workers’ during the vote,Footnote 56 with workers receiving ‘500 pesos if they snap photos as evidence of casting their ballot in favor of the CTM-affiliated SITPME’.Footnote 57 In the case of Teksid Hierro, Teksid fired seven workers after they were interviewed by the Department of Labor Attaché as part of the investigation, and they were not reinstated even with the remediation agreement (IMLEB, 2023). At VU Manufacturing, workers in the protection union took public their concerns over the leader of one of the other unions, raising fears about her personal safety.Footnote 58 At Unique Fabricating, there was allegedly interference by an official from the state's local labor secretariat.Footnote 59

6. Insights from and Questions for Political-Economy Research

Answers to important questions for political–economic research may speak to the sustainability of the RRM. These include why and how did Mexico and the United States agree to the RRM? Furthermore, what are the impacts, including unintended consequences, of the RRM on Mexican workers, local firms in Mexico, and multinationals?

6.1 Why did the Mexican and US Governments Agree to the RRM?

Multiple strands of political–economic research may be required to fully understand why and how Mexico and the United States agreed to the RRM and whether it will benefit each country in the aggregate and/or have substantial redistributive consequences.

One puzzle is why Mexico would agree to an RRM that is so asymmetric. A contributing explanation may come from the commitment theory of trade agreements (Staiger and Tabellini, Reference Staiger and Tabellini1987; Maggi and Rodríguez-Clare, Reference Maggi and Rodríguez-Clare1998, Reference Maggi and Rodríguez-Clare2007). Governments sometimes face a time-consistency problem and are unable to follow through implementing a policy tomorrow even if it was optimal when announced today. By tying its own hands in the future to ward off domestic lobbying forces, the government can sometimes improve aggregate outcomes (increase efficiency) for the country as a whole.

Suppose the pre-USMCA problem was that local firms in Mexico had monopsony power over workers that was entrenched institutionally by protection unions. A welfare-maximizing Mexican government might want to break the status quo by allowing workers to form new unions and bargain collectively, as doing so could improve efficiency by moving wages closer to the marginal revenue product of labor. (The desire to act could also be politically motivated, as the move would reallocate firm profits toward workers through higher wages.) However, even though it may be optimal to announce such a policy today, the government could renege on its promise tomorrow (after being lobbied to do so) unless it was able foreclose on the possibility of policy reversal. The RRM in the USMCA could be viewed as an external commitment device the Mexican government had voluntarily adopted to help it follow through with policies it would like to implement in the future.

A second puzzle has to do with the value of the RRM to the United States. The static effect of raising the wages of Mexican workers is higher prices for US imports and a reduction in US economic welfare. The literature on issue linkage – tying labor standards to trade sanctions – suggests at least two potential ways to counteract this static loss.Footnote 60 The ‘participation’ strand of that literature often finds that coalitions to coordinate trade sanctions may be needed to encourage other countries to participate in another issue area. (The most familiar issue linkage proposal may be between governments seeking to reduce carbon emissions [see the climate clubs approach of Nordhaus, Reference Nordhaus2015].) Under this theory, the RRM might play two roles when it comes to participation. Tying labor rights to trade could encourage Mexico to participate in broader efforts to improve worker conditions. Bringing labor into the trade agreement through the RRM could also help the United States find a large enough domestic political coalition willing to support continued open trade with Mexico.

The issue linkage literature on enforcement raises at least one other important question. Enforcement often arises in the context of repeated game models in which at each stage of the game, each government has an incentive to impose high tariffs. The equilibrium of the one-shot game without a trade agreement is the standard (suboptimal) prisoner's dilemma outcome of each country imposing high tariffs. In the repeated game, governments can cooperate and reduce tariffs (i.e., form a trade agreement) in which enforcement is modeled as one country punishing its trading partner with higher tariffs for cheating. That threat is what sustains lower, cooperative tariffs.

How does the RRM affect cooperation over trade alone (through tariffs)? Does a government's use of trade sanctions to enforce a partner's labor commitments dilute its ability to ensure that the partner keeps tariffs low?Footnote 61

Consider a hypothetical example. Suppose the United States deploys its full arsenal of trade sanctions to remediate labor violations at all of Mexico's facilities and ‘uses up’ its ability to threaten to retaliate against Mexico. Mexico could respond by raising its tariffs on US exports out of recognition that there is no additional penalty to doing so. Does using threats over US imports to improve worker rights make it more difficult to keep Mexico open to US exports? Does the asymmetry in the Mexico–US trade relationship help prevent such an outcome? The fact that Mexico's exports to the United States are so much larger than its imports may mean that the United States has ‘extra’ enforcement power to deploy tariff threats not only to keep Mexican tariffs on US exports low but also to help the Mexican government enforce domestic labor commitments through the RRM.

6.2 What Happens in Mexico When the RRM is Implemented?

This article has only begun to examine the impact of the RRM on labor market outcomes and behavior within Mexico, including its potential unintended consequences.Footnote 62 The full impact may extend well beyond the effect on workers at facilities facing RRM situations. To help frame how researchers can more systematically study such impacts in the future, we appeal to the theoretical framework provided by Alfaro-Ureña et al. (Reference Alfaro-Ureña, Faber, Gaubert, Manelici and Vasquez2022), which examines the implications of multinational firms imposing responsible sourcing codes of conduct policies on their suppliers in developing countries.Footnote 63

Suppose there are three firms: a multinational headquartered in the United States, a local supplier to a multinational in Mexico (Firm A) and a second firm (Firm B) in Mexico that, for some exogenous reason, is outside of the reach of the RRM.Footnote 64 Here, introduction of the RRM can be thought of as similar in its economic effects as the multinational firm's voluntary imposition of a responsible sourcing policy on its suppliers. The threat of RRM-type trade sanctions (from the US government) would hit the multinational's import demand for inputs from Firm A in a way similar to the hit the multinational would face if it did not impose responsible resourcing in response to consumer threats of boycotts for its output. Both are designed to raise worker wages at the local supplier to the multinational.

The Alfaro-Ureña et al. (Reference Alfaro-Ureña, Faber, Gaubert, Manelici and Vasquez2022) theory identifies a number of competing distributional effects and channels to keep track of and to identify the full effects of the policy. On the positive side, workers at Mexican Firm A would expect to enjoy higher wages and better benefits because of the existence of the RRM and the threat of trade sanctions. (Several examples have arisen among the RRM situations summarized in Table 4, though there is also one where the plant shut down and workers presumably lost their jobs.)

On the negative side, workers at Firm B could be hurt through two main channels. Under the first, the higher wage mandated by the RRM could reduce Firm A's demand for workers. If it does, the freed-up workers originally employed at Firm A will leave and seek employment at Firm B. The sudden increase in the supply of workers available to Firm B will put downward pressure on wages at that firm.

The Mexican government's labor reform push to fight monopsony power could prevent wages at Firm B from falling; however, if Firm B is not able to absorb all of the workers displaced from Firm A, the result could be increased unemployment or Mexican workers moving into the informal sector. Alternatively, if the government misdiagnosed the problem and low wages were not the result of firms holding monopsony power, raising wages may shrink (and not expand) employment.

The second channel to consider involves the impact of RRM-induced changes on output prices. Mexican workers are also consumers; they care not only about their nominal wages but also about the purchasing power of their real income. Suppose Firm A supplies both the US-headquartered multinational and domestic firms in Mexico. Firm A will pass along some of the increase in wages in the form of higher local prices, hurting workers through the consumption channel.Footnote 65

A third, potentially positive (offsetting) effect depends on whether the RRM increases the US multinational's demand from Mexico. The analogy is to how responsible sourcing policies could, in theory, lead US consumers to pay more and switch toward multinational brands that adhere to such policies. Though unlikely, it is possible that some US consumers switch their purchasing toward multinationals that source from Mexico relative to other countries because the RRM signals that Mexican workers are being treated better than workers in countries without an RRM.Footnote 66 If they do, the increase in demand for supplies from Firm A could mean more employment and higher wages for its workers.

A key difference between the RRM and responsible sourcing is that the latter was rolled out globally (on suppliers in all developing countries) whereas the RRM currently applies only to facilities in Mexico. Global application meant that there was less of an incentive for a multinational to shift buying away from one developing country to another in response to responsible sourcing. For the period in which only Mexico is subject to RRM review, there may be an incentive for multinationals to switch sourcing to non-Mexican suppliers.Footnote 67

The RRM affects both Mexico and the United States through many channels. Examining data on worker outcomes at facilities facing RRM situations is important, but it is only one part of the story.

7. Preliminary Policy Lessons and the Future

With only 11 uses in the first three years of the RRM, data with which to evaluate the mechanism remain scarce. Many aspects of how the RRM works are unknown and difficult to evaluate. For example, the data reveal little about whether the RRM has a deterrent effect, and they shed almost no light on the long-run outcome for Mexican or US workers overall. It will also be important to await studies of the effectiveness of the capacity-building and technical assistance initiatives designed to help Mexico implement its labor reform program. Much of the process remains untested. Only one of the RRM situations had resulted in the request for formation of a panel request, and the outcome of that panel was still unknown as of the time of writing. Furthermore, the United States has not yet applied any of the remedies afforded to it under the USMCA (because all situations to date have been remediated successfully). Nevertheless, we offer here some preliminary reflections on the RRM experience to date.

The RRM is operating somewhat like a pilot program. US policymakers have deployed it cautiously and relatively infrequently to start, though the pace may be increasing (with six situations alone in the first half of 2023, more than half of the three-year total). Most of the situations to date have been resolved successfully, in the views of the two governments, and relatively quickly – an important departure from the US case against Guatemala. The Mexican government and the USTR have claimed victory, at least at some level, for Mexican workers, in most of the RRM situations that have been brought forward. However, some Mexican officials have expressed concern about the asymmetric nature of the RRM and issues of domestic sovereignty and urged the USTR to use the tool as a ‘last resort’ to ‘reinforce’ rather than ‘replace’ Mexico's labor institutions.Footnote 68 Finally, there is at least one situation in which a company did not comply with an announced remediation plan and instead shut down the plant.

Labor-oriented governments in both Mexico and the United States seem intent on using the tool to rebalance the benefits at facilities in Mexico toward workers. Nevertheless, achieving even a common goal requires coordination and cooperation, not one government blindsiding the other with an unexpected or unworkable situation. In practical terms, an effective case requires the complementary organization of two governments that, at any moment in time, may have a different prioritization for their resources.

For the most part, firms appear to have been complying with demands to support a fair process – one that allows workers to vote out old and vote in new unions (and then bargain collectively for higher wages, reinstatement of lost jobs, back pay, etc.) – despite facing tremendous uncertainty about the worst-case scenario for (costs of) failure to do so. At some point, tariff benefits may be withdrawn; greater clarity on their significance could then shape future behavior. The reality of the benefits of tariff-free trade could affect this calculation as well. Put differently, the threat of loss of duty-free trade may lose its bite as a penalty if the rules of origin requirements in the USMCA become so onerous that firms decide to pay the MFN tariff instead. This outcome was foreshadowed by a US International Trade Commission analysis that found that these new cost-raising features of the agreement were likely to drive up the price of buying a car assembled in North America (USITC, 2019). It would redistribute wealth from American consumers to auto workers, especially in the United States, but leave the overall US economy worse off than it was under the NAFTA rules of origin.Footnote 69

US and Mexican labor interests could also diverge from their currently aligned views. For example, suppose unions in the United States push RRM uses so far that compliance increases the costs of production in Mexico to the point at which they outweigh the comparative advantage-based reasons for trade between the United States and Mexico. In this case, firms might leave Mexico, reshoring to the United States or moving to countries not subject to an RRM. The loss of these jobs would hurt Mexican workers; worker outcomes are a function of wages and employment, not wages alone.

Where might facility-specific RRMs go from here? Labor advocates argue that the RRM is the new floor for the United States in any future trade agreements, much like the 10 May 2007 agreement between House Democrats and the George W. Bush administration that created a bipartisan consensus on trade negotiations by inserting enforceable labor and environmental standards into new US agreements (Destler, Reference Destler2007). The idea of some sort of facility-specific labor compliance tool was agreed as part of the negotiations between the United States and 13 other countries over the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF). The ‘proposed Agreement would also create a mechanism to cooperate with partners to address facility-specific allegations of labor rights inconsistencies’.Footnote 70 If IPEF precludes market access negotiations in the form of traditional tariff liberalization, one possibility may be that negotiators include only the trade facilitation carrots of grants for capacity building and training and not sticks (such as the suspension of liquidation, as is the case in the USMCA RRM).

Could facility-specific RRMs extend beyond labor to help enforce environmental standards? For example, suppose the trading system accommodates carbon border adjustment mechanisms that allow importing countries to impose differential import taxes based on the carbon intensity of foreign production. How would the ability to enforce – through targeted trade sanctions (sticks) or technical assistance (carrots) rapidly and at the facility-level abroad affect such negotiations and agreements? The RRM seems more likely to work and be useful in trade relationships in which the two governments have a common interest in enforcement and the main concern is a domestic problem of commitment. In future trade agreements, where such agreements are entered into voluntarily, such a prioritization would need to take both sides into account.

Such efforts would also likely need to be tailored to the needs of the local environment. The RRM in the USMCA may help tackle the protection union problem, collective bargaining, and Mexico's concerns about monopsony power. But Mexican workers (and workers elsewhere) face other problems, including a sizable informal sector in which workers may be treated even worse. Mexico also has a wide gender wage gap as well as low employment and labor market participation rates for women (OECD, 2020). Mexican workers have been exposed to their own China shock of both increased imports from China and competition for the goods they produce in third country export markets (like the United States), as China and Mexico share many of the same comparative advantages (Robertson et al., Reference Robertson, Halliday and Vasireddy2020). Mexico also faces challenges with migration, cartels, human trafficking, and other labor market worries that the RRM is not well positioned to help address.

The RRM is likely to be a transitional policy instrument. As Mexican labor rights improve, or as fatigue grows in its application, it could be phased out or fall into desuetude.

Many stars had to align to craft an RRM that targets the protection union problem in Mexico. Absent Trump, the panel decision in the Guatemala case, the asymmetric nature of North American automobile trade, the timing of the López Obrador transition, or the retaking of Congress by Democrats in 2018, the RRM is unlikely to have emerged in its current form. Policymakers seeking to introduce similar mechanisms in other international agreements will need to find incentives and motivations that are different from those that led to the RRM in the USMCA.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sonali Chowdhry, Kristin Dziczek, Crawford Falconer, Joe Francois, Bernard Hoekman, Gary Hufbauer, Nuno Limão, Giovanni Maggi, Douglas Nelson, Mona Pinchis-Paulsen, and Michele Ruta for helpful comments and Chris Rogers for sharing data. Yilin Wang and Julieta Contreras provided outstanding research assistance. Nia Kitchin and Alex Martin assisted with graphics.