Introduction

In recent years, the focus of the kin-state citizenship literature has shifted away from states toward individuals’ understanding of kin-state citizenship. It has been shown that the reasons behind individual decisions to acquire kin-state citizenship are not necessarily the same as rhetoric attached to such policies coming from the kin-state (Waterbury Reference Waterbury2020, 804).

Scholars argue that the transborder ethnic communities view citizenship through three dimensions: symbolic, instrumental, and legitimacy. They view citizenship as a formal recognition of previously held feelings of belonging and utilize it to claim the belonging (Pogonyi Reference Pogonyi2019), through opportunities it provides in comparison to the opportunities the home-state provides (Harpaz Reference Harpaz2019b; Harpaz and Mateos Reference Harpaz and Mateos2019) and as compensation for the past injustices that split the ethnic community in the first place (Knott Reference Knott2019).

However, scholars have looked only at the citizenship acquisition process. I argue instead that the individual’s understanding of citizenship changes over time, and the meanings they ascribe to citizenship evolve from the reasons and context of acquisition. Thus, rather than imagining citizenship as a fixed category, individuals align the meanings they ascribe to it with current circumstances and overall kin-state policies. Therefore, this article aims to look beyond the acquisition process alone and explore how individuals’ understanding of citizenship changes in the long term and what impacts the change.

The article builds on the case of ethnic Croats in parts of Herzegovina, where the Croat community makes up the majority (from here onward Croats in Herzegovina). Most of them acquired Croatian citizenship en masse back in the 1990s, and ever since, the newborn members of the community acquire it through their parent’s decision.

Overall, the article finds the changes across each dimension of citizenship. First, looking at the symbolic dimension of citizenship, the article shows how the perception of their inclusion into the kin-state impacts how individuals utilize citizenship. In other words, during the 1990s, when their inclusion into Croatia was indisputable, Croats in Herzegovina utilized citizenship primarily to distance themselves from the home-state and claim recognition of their kin-state ties by other ethnic communities in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH). However, since the 2000s, perception of their inclusion into the kin-state decreased among Croats in Herzegovina as a consequence of, in their view, experiences of traveling to or living in Croatia, changing rhetoric toward them in Croatia, and further strengthening of the border between them and Croatia. Since then, Croats in Herzegovina have utilized citizenship also to claim recognition of their belonging to the kin-state by their co-ethnics in Croatia. The findings suggest that kin-state citizenship fails to overcome the distance between co-ethnics from the two sides of the border.

Second, the article shows that the type and extent of opportunities citizenship provide impact the meanings individuals ascribe to the instrumental dimension of citizenship. Croatian citizenship provided two types of opportunities to Croats in Herzegovina at different times. First, during the 1990s, citizenship ensured protection against immediate threat and material deprivation and contributed to an understanding of citizenship as protective. Second, as the circumstance in BiH improved, the citizenship only enhanced already existing opportunities in BiH and contributed to an understanding of citizenship as pragmatic. Moreover, since Croatia joined the European Union (EU), the opportunities citizenship provided have expanded significantly. Thus, in addition to access to Croatia’s welfare state and labor market, Croats in Herzegovina gained ample opportunities across the EU, which impacted how they understand the instrumental value of citizenship.

Third, the article shows that the routinization of citizenship practices impacts the meanings individuals ascribe to the legitimacy dimension of citizenship. Croatia introduced the kin-state citizenship in the 1990s as compensation for the separation of the transborder ethnic community and the contributions Croats from Herzegovina made during the war in Croatia. The latter certainly strengthened the attachments. However, younger generations see citizenship as a consequence of routinization and think of it as a legal entitlement and not as legitimate compensation. In that way, they also distance themselves from controversies surrounding the kin-state policy.

More broadly, the findings suggest that the individuals respond to policy changes by aligning the meanings they attach to the policy’s entitlements and by expressing their views on the policy through the practice of entitlements. Therefore, future research on kin-state policies should look more closely at the interplay between state policies and individual responses to the policies. In that way, we can establish more precisely the impact of the kin-state policy on individuals.

Literature on Kin-State Citizenship

The most powerful and controversial of all kin-state policies is the expansion of kin-state citizenship (Waterbury Reference Waterbury2010, 142). It explicitly challenges the sovereignty of the home-state and the position of the transborder community vis-à-vis both states.

As the number of states adopting the kin-state citizenship policies increased, academic research on the reasons behind the state’s adoption of the policy and potential impact also grew (King and Melvin Reference King and Melvin2000; Fowler Reference Fowler2004; Iordachi Reference Iordachi2004; Štiks Reference Štiks2010; Pogony, Kovács, and Körtvélyesi Reference Pogonyi, Kovács and Körtvélyesi2010; Dumbrava Reference Dumbrava2014, Reference Dumbrava2019; Herner-Kovács and Kántor Reference Herner-Kovács and Kántor2014; Waterbury Reference Waterbury2014, Reference Waterbury2017; Stjepanović Reference Stjepanović2015; Udrea Reference Udrea2017; Bauböck Reference Bauböck2019). Overall findings suggest that kin-states primarily engage with kin-state policies for domestic reasons, but it remains unclear what the long-term impacts are (Waterbury Reference Waterbury2020, 803).

In recent years, the focus has shifted on how the transborder ethnic community’s members justify the acquisition of kin-state citizenship and frame their engagement with it (Knott Reference Knott2015b, Reference Knott2015c, Reference Knott2019; Kallas Reference Kallas2016; Wallace and Patsiurko Reference Wallace and Patsiurko2017; Vasiljević Reference Vasiljević2018; Harpaz Reference Harpaz2019a, Reference Harpaz2019b; Harpaz and Mateos Reference Harpaz and Mateos2019; Pogonyi Reference Pogonyi2019).

The bottom-up approach expands understanding of the impact kin-state policies have at the individual level. Kallas (Reference Kallas2016) suggests that the transborder community does not always approve of how the kin-states engage with the community. This study does not discuss such claims, but it focuses on the meanings individuals ascribe to kin-state citizenship and the ways in which kin-state citizenship shapes their everyday social context.

Scholars have established three mutually non-exclusive dimensions through which members of the transborder ethnic community view kin-state citizenship:

-

1. Identity/symbolic dimension: kin-state citizenship “strengthens the holder’s sense of belonging to the national group” (Pogonyi Reference Pogonyi2019). The transborder community can also utilize citizenship as a means of identity management – either to claim distance from the majority community across the home-state or to claim the community’s attachments to the kin-state and Europe.

-

2. Strategic/instrumental dimension: members of the transborder ethnic community acquire kin-state citizenship for instrumental reasons. This “trend reflects individuals’ interest in improving their position within a global system of inequalities premised on citizenship” (Harpaz and Mateos Reference Harpaz and Mateos2019).

-

3. Legitimacy dimension: acquisition of kin-state citizenship rectifies perceived past injustices. Knott (Reference Knott2019) goes beyond the dichotomy of the first two dimensions and shows how the discourse of legitimacy underpins kin-state citizenship. The discourse of legitimacy serves to normalize and explain the prevalence of kin-state citizenship beyond individuals who identify with the kin-state.

However, scholars mainly focus on real-time citizenship acquisition and the reasons behind the individual decision to acquire citizenship. By exclusively looking at the real-time acquisition, the research only accounts for people motivated to acquire citizenship and willing to invest additional effort or resources required for the acquisition process at the given time. Moreover, their research is only focused on cases where the kin-state policy was recently introduced.

The case of Croats in Herzegovina uncovers a different perspective for three reasons. First, Croatian citizenship was offered to Croats in Herzegovina en masse during the 1990s, and since then, the individual members have had the opportunity to experience the advantages and disadvantages of having kin-state citizenship. Second, the kin-state and the home-state circumstances have changed significantly since then, primarily with the end of the war in BiH and Croatian accession to the EU. Therefore, the circumstances, which motivated individuals to acquire citizenship back in the 1990s, might not exist anymore, and it is crucial to understand how participants reconcile with the decision today. Third, the time difference provides an opportunity to look at how individuals respond to changing perceptions of inclusion into the kin-state, which is shaped by the transformation of the kin-state policies and the discourse across Croatia surrounding the policy. This is particularly important for younger generations, born into citizenship, that is, whose parents acquired citizenship for them while they were still young. They never had the opportunity to choose citizenship, nor were they ever required to think of citizenship as a consequence of past events.

Therefore, the case of Croatia expands our understanding of kin-state citizenship’s impact by adding a long-term perspective to existing research. It also challenges the three dimensions established by the literature on kin-state citizenship by showing how individuals practice citizenship independently of kin-state aims.

Methodology

The study builds on the data collected in 2019 during two visits to Herzegovina. The research plan was granted the University of Liverpool Ethics Committee approval (number 3872) in preparation for the fieldwork.

The data include semi-structured interviews and focus groups conducted with 40 individuals in Herzegovina who identify ethnically as Croats regardless of their attachments to Croatia. The research participants vary in age, gender, place of residence, education, and income level. However, the aim was to explore multiple perspectives and contradictory narratives rather than look for a representative sample (Knott Reference Knott2019). I used the snowball method to reach out to participants, starting with six previously established personal contacts with people of different backgrounds and four email and phone requests to different NGO organizations across Herzegovina. Participants were then encouraged to invite other suitable candidates to join the research.

Several research participants perform executive political functions across Herzegovina – instead of TG-3, their quotes are referenced with TG-2 notation. Three focus groups have been conducted to explore citizenship discourse, which can be captured more precisely within the focus group discussion (Sokolić Reference Sokolić2016). The aim was to ensure that the interview questions do not depart significantly from what participants find essential when discussing citizenship. Focus groups are referenced as FG- followed by CTL, STD, or WV. The first focus group took place in the city of Čitluk, with four participants, aged between 55 and 61, and the majority were women. The second was conducted with students aged between 19 and 22, half of whom were women, and the third focus group consisted of war veterans from an organization that supports the veteran community.

Research participants were encouraged to discuss how they acquired Croatian citizenship and what kin-state citizenship means for them today. They reflected on the reasons behind the decision to acquire it and discussed how they use the kin-state citizenship today and how it shapes their everyday social context. Their stories contribute to understanding citizenship as something more than just a political/legal institution, but as something that is experienced in a consequential way at the level of everyday life (Knott Reference Knott2019; Reference Knott2015a).

Therefore, the article is informed by the experiences and practices of individuals. To analyze the data, I used thematic analysis (Attride-Stirling Reference Attride-Stirling2001), and in this study, I explore the categories of citizenship that emerged through the analysis.

Croats in Herzegovina – A Transborder Ethnic Community

Croatia and BiH claimed independence from Yugoslavia as the republics across Yugoslavia could not reach an agreement in the early 1990s on the future outlook of the common state. The nationalizing principle of establishing new states for and of dominant ethnic communities prevailed, which in Croatia caused a war between an ethnic majority comprised of Croats and a minority Serb ethnic community (Brubaker Reference Brubaker1996, 55; Bose Reference Bose2002; Ramet Reference Ramet2002; Caspersen Reference Caspersen2009). The circumstances in BiH, which consisted of three ethnic communities, proved more detrimental. The lack of agreement on the common state that would accommodate all three ethnic communities gave precedence to those among Bosniak, Croat, and Serb communities, which aimed to establish states only for and of members of their own community (Brubaker Reference Brubaker1996). A wealth of literature has explored the catastrophic humanitarian effect such policies left on BiH’s soil – the genocide against the Bosniak ethnic community, ethnic cleansing across BiH, and other crimes against humanity all communities conducted (Burg and Shoup Reference Burg and Shoup1999; Bose Reference Bose2002; Caspersen Reference Caspersen2004; Ramet Reference Ramet2006; Tabeau and Bijak Reference Tabeau and Bijak2005). Finally, the international intervention brought the three sides together to sign a Dayton Peace Agreement in 1995, establishing BiH as an asymmetric federation, made up of Republika Srpska (RS) and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH). The border split the Croat ethnic community between Croatia and BiH while most Croats in BiH remained in Herzegovina, part of FBiH.

After the failed attempts to create their own statelet in BiH across Herzegovina, which Croatia extensively supported, the Croats of BiH remained distant to BiH (Subotić Reference Subotić, Ramet and Valenta2016; Grandits Reference Grandits2007; Hoare Reference Hoare1997; International Crisis Group 1998). Their focus remains at the cantons across FBiH, where they make the majority, while at the state level, they claim the recognition of constitutive status, which, in their view, includes a fair share of institutional ownership and ethnic entitlements. This has created recurring tensions with the Bosniak and Serb ethnic community and shifts the Croat community’s attention back toward areas where they can successfully claim ethnic ownership and entitlements – toward cantons of FBiH where they make a majority, and toward Croatia (Subašić Reference Subašić2020). Meanwhile, Croatia has succeeded in establishing a state for and of a Croatian ethnic community, where the community members can claim ethnic ownership over institutions and institutional entitlements. In line with this policy, Croatia awarded all Croats across the globe, including Croats from BiH, with Croatian citizenship (Koska Reference Koska2011).

In this study, I look beyond the recent acquisition and explore how the meanings ascribed to citizenship change in the long term. All research participants who hold dual citizenship acquired it either during the 1990s or while they were very young when the circumstances were significantly different from today. Back then, Croatia’s EU membership was only a distant possibility, BiH was undergoing a state-building process, and the kin-state policy was widely accepted across the kin-state.

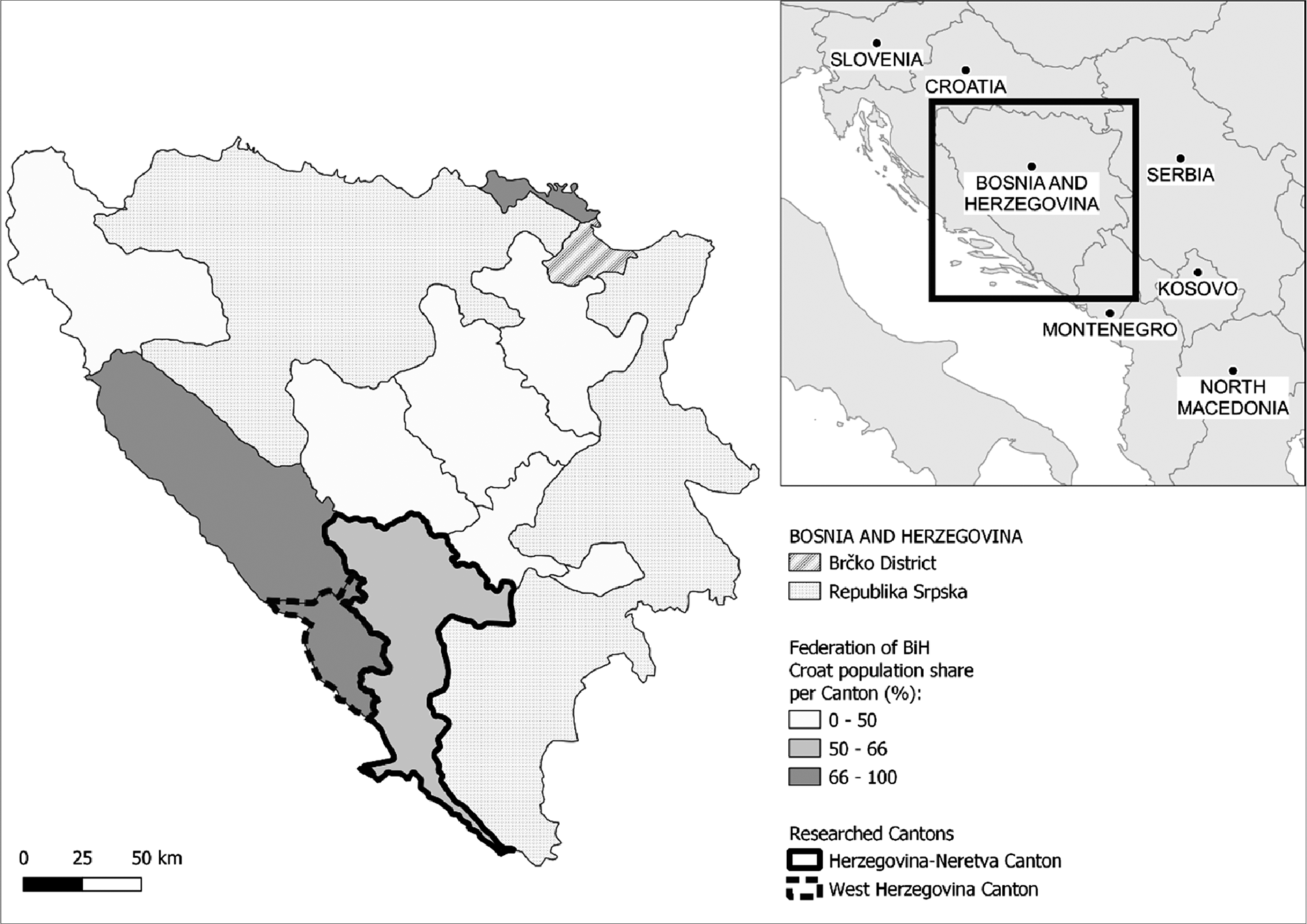

According to the most recent population census conducted in 2013, 544,780 Croats lived in BiH, making roughly 15% of the population (Agencija za statistiku Bosne i Hercegovine 2019). Most of them, 497,883, lived in FBiH, where they made up 22% of the population. My research is focused on the two cantons, part of FBiH, where Croats make up the majority: Hercegovina-Neretva Canton (Hercegovočko-neretvanski kanton, HNK) and West Herzegovina Canton (Zapadnohercegovački kanton, ZHK). Members of the Croat community represent 98% (93,725) of the population of HNK and 53% (118,297) of the population of the ZNK. Map 1 shows the administrative organization of BiH, highlighting areas discussed, including the two cantons.

Map 1. Administrative organisation of BiH and the Croat population share across cantons (designed by author).

The focus is on HNK and ZHK for three reasons. First, this was where the Croat community during the war in BiH tried unsuccessfully to establish the Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosna (Hrvatska Republika Herceg-Bosna, HR HB), a Croat community statelet. One of the war-related consequences was the increased share of Croats against members of other ethnic communities in the two cantons. Second, scholars (Knott Reference Knott2015c) have recognized the different dynamics across cases where transborder communities make up the majority at the substate level compared with cases where they only constitute a minority ethnic group. Third, the two cantons share the border with Croatia.

When it comes to Croatian citizenship, from 1991 to 2010, Croatia admitted 678,918 applicants to Croatian citizenship from people who held BiH’s citizenship at the time of application (Koska Reference Koska2013). Annual data are not available for the period. However, between 2005 and 2019, Croatia admitted a total of 28,315 applicants (MUP 2019a). Therefore, it is safe to assume that most Croats in Herzegovina acquired Croatian citizenship during the 1990s and early 2000s. The official number of Croatian citizens with residency in BiH is 384,631 (MUP 2019b), but individuals are not required to report their residency, which implies their number is much higher, suggesting the overwhelming majority of Croats in BiH hold Croatian citizenship and acquired it a long time ago.

Croatian Kin-State Citizenship Policy

Franjo Tuđman, who was president of Croatia in 1992, highlighted in his letter of BiH’s recognition that ”Croatia offers dual citizenship to all Croats [in BiH] who wish to obtain it.” He added that the two countries should ”regulate the issue by a bilateral agreement” (Tuđman and Bilić Reference Tuđman and Bilić2005, 87). However, the bilateral Agreement on Dual Citizenship was signed only in 2007 and ratified four years later in 2011 (RH 2007). Meanwhile, most Croats in BiH had already acquired Croatian citizenship. The available data and the research participants’ recollection show that the acquisition happened en masse after the Washington Agreement was signed in 1994Footnote 1. A research participant, with the help of his wife, shared his memory of when they applied for citizenship and how they experienced the process:

The Croatian [citizenship certificate] started to be requested [by the people] around 1994, 1995. Not before. Maybe, some people did before, but in 1994, 1995 it was en masse. Before that, I remember I travelled, I used BiH’s passport. [But after that] it went en masse. Last kid got it straight away, [woman adds] “because he was born in Croatia,” the same for the other, they were born in Croatia, during the war [when we were in refuge]. The others did not have it before 1994. [woman adds] “Then, I think I just went and took it for all of us, at the same time. You could do it here, in Mostar, you did not have to go to Croatia, I remember there were huge queues” (TG-3-12).

In 2001, the Council of Europe recognized the adverse impact of kin-state policies on interstate relations established in the Report of its advisory body, the Venice Commission (2001). Then in 2008, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) issued a recommendation suggesting the states “should refrain from granting citizenship en masse to citizens of another state” without the approval of the respective state (OSCE HCNM 2008). The OSCE High Commissioner recognized that such an approach “has the potential to create tensions. That is particularly likely to happen when citizenship is conferred en masse, i.e. to a specified group of individuals or in substantial numbers relative to the size of the population of the state of residence or one of its territorial subdivisions” (OSCE HCNM 2008, 19). By that time, Croatia had already signed the Agreement on Dual Citizenship with BiH and aligned its policy with the Council of Europe and OSCE recommendations despite previously awarding the citizenship in a way OSCE found potentially inappropriate. This ensured Croatia was able to maintain the kin-state policy and further its accession toward the EU, and eventually join the EU in 2013.

The Symbolic Dimension of the Kin-State Citizenship

As outlined in the introduction, Croatian citizenship provides the opportunity for Croats from Herzegovina to formalize previously held subjective feelings of belonging that they recognize and appreciate. In his research, Pogonyi (Reference Pogonyi2019) also established how kin-state citizenship allows individuals to utilize it as a means of identity management. He argued that individuals utilize citizenship to claim distance from the home-state majority, belonging to the kin-state and to Europe.

The case of Croats from Herzegovina adds to the symbolic dimension by showing how individuals’ perception of inclusion into the kin-state impacts how they utilize citizenship. During the 1990s, Croats in Herzegovina utilized citizenship primarily to claim recognition of their belonging to Croatia by other ethnic communities across BiH. However, once their perception of the inclusion into the kin-state decreased, Croats from Herzegovina utilized citizenship to claim recognition of their belonging to Croatia by their co-ethnics in Croatia.

All of the research participants, except one, held Croatian citizenship, and the majority expressed how they hold Croatian citizenship in recognition of their subjective feelings of belonging. In discussion with students from the focus group, this has become evident. Each student suggested how they hold citizenship simply because they “feel attached to Croatia” (FG-STD-F1). Four of them have family relatives in Croatia, and by acquiring citizenship, they suggested, the family relations are also strengthened. One participant used the family relation to depict the relationship between Croatia and the transborder ethnic community. He said, “I have citizenship because I feel attached to Croatia, and I think” with awarding citizenship to Croats of Herzegovina, Croatia acknowledges “the responsibility to take care of us. When I say to take care, I mean as if they are a mother and we are a child” (FG-STD-M3). The discussion in other focus groups was very similar (FG-CTL-FG).

Some students used the sports examples and the atmosphere in Herzegovina when the Croatian team plays to suggest how they feel attached to Croatia regardless of citizenship. “When it comes to sport, all Croats from Herzegovina support the Croatian national team. However, when it comes to BiH’s sport, Croats simply do not feel attached to BiH’s national team” (FG-STD-M3). Other participants throughout the fieldwork also used sport to suggest how citizenship formalizes attachment Croats from Herzegovina experience (NO-TG-ST, NO-TG-CTL, TG-3-3, TG-3-11, TG-3-12, TG-3-14, TG-3-18, TG-3-23M, TG-3-24F1, TG-3-24F2).

The following statements illustrate how formal recognition strengthens the existing feelings of belonging: “I did not acquire Croatian documents to make it easier for me, but simply because I want to express the attachment. I feel that when I hold the Croatian ID, I belong to Croatia” (NO-FG-CTL). Thus, passports, IDs, and other documents that Croats from Herzegovina hold bear an emotional, symbolical, and formal value – it reconfirms their belonging to Croatia. One participant’s reflection captures well all aspects of identity management through the use of documents:

“I think you can’t divide something that the heart brings together. We thirst for Croatia. Why do I have a Croatian ID? When somebody asks me for an ID, I will always show a Croatian ID, even if I have two IDs. Why? Because it is emotional for me. I have the FBiH ID, but I will always give the blue and pink one. It is simply an emotional attachment. It was hard for me to withdraw my address in Croatia; it means the world to me” (TG-3-12).

Another participant, aiming to express how citizenship is a formal recognition of an attachment she already holds, was puzzled by expressing her belonging. She said, “well, you feel somehow, you are not in Croatia, but you are with Croatia, it is our second homeland” to which she stopped, rethought what she said and added “I mean it is our main homeland” (TG-3-21). Her reflection precisely outlines the insecurities arising from the position between the two states. Politicians in Croatia often trigger competing claims between the two states, not least concerning the belonging of a community.

One political representative, a research participant from Croatia, stated in the interview that he thinks “many Croats from Herzegovina, had there not been a double citizenship, would choose the Croatian rather than BiH’s citizenship” (TG-ZG-2). The “second homeland” is used to suggest the special status Croats from Herzegovina have concerning both states. However, the second homeland usually refers to Croatia, even if some, such as Kolinda Grabar Kitarović, an ex Croatian president, used to say that BiH is a “second homeland” to Croats in BiH (N1 2018). She intended to highlight that Croats from Herzegovina are equal to Croats from Croatia. Unlike those who put Croatia “second” to emphasize Croats’ constitutive, core status in BiH.

During the 1990s, kin-state citizenship was introduced to distance Croats in BiH from the home-state and bring it closer to the kin-state. It was a compromise between recognizing the Croat statelet in BiH and the inclusion of the community into the home-state. Their belonging to the kin-state was indisputable. Individuals back then utilized citizenship primarily to claim recognition of their distance from the home-state by other ethnic communities in BiH. However, Croats from Herzegovina claim that they utilize citizenship today primarily to seek recognition of their belonging to the kin-state by their co-ethnics in Croatia. It is, in their view, a consequence of changing perceptions of their inclusion into the kin-state. The need to claim recognition by co-ethnics almost three decades after belonging had been formalized suggests that, contrary to expectation, the distance between the ethnic community from the two sides of the border only increased.

Three factors contributed to their perception of decreased inclusion into the kin-state. First, several young participants explained how their perception of inclusion changed when they worked or traveled in Croatia (TG-3-1, TG-3-6, TG-3-7, TG-3-16, TG-3-22, TG-23-M, TG-3-12, TG-3-16, FG-CTL-F). Many of them experienced adverse treatment from their co-ethnics across Croatia, which led one of them to realize that “she does not belong there” (TG-3-7). In the participants’ view, the second factor was the public discourse in Croatia that appeared when the kin-state aligned its policy with the Council of Europe and OSCE recommendations. One participant explained how “they steered people up [in Croatia] against people from Herzegovina [back then]. That same portrayal of us, from that time, exists even today in the media” (TG-3-8). “The argument exists that we are only taking money” (FG-CTL-M), another participant stated. One participant conveyed how she often finds herself “accused and attacked” while in Croatia because the Croats in Herzegovina apparently “only use Croatia” (TG-3-12). Finally, since Croatia joined the EU, the border between the ethnic community has strengthened. For some Croats in Herzegovina, that was another signal contributing to their perception of decreasing inclusion into the kin-state (TG-3-06, TG-3-07, TG-3-12, TG-3-14, TG-3-16, TG-3-22, TG-3-23). As one participant put it, “it feels as if I am a criminal when I come to the border … while other Croats [from Croatia] will enter [Croatia] with no problems” (TG-3-23).

These participants utilize citizenship primarily to claim recognition of their belonging to Croatia by their co-ethnics in Croatia, such as the participant in the following quote:

When I am in Croatia, I feel like in Herzegovina. When I compare it to how I feel in Ljubuški, my home, I feel local, similar to how I feel in Croatia. Even if [people] in Croatia look at Croats from Herzegovina with slight suspicion, and I feel that. I used to have a Bosnian passport, and frankly, I felt [strange]. As if some part of me has been artificially imposed on me. It felt as if I am not on my own. I live here, and BiH is a nice state, but Croatia is still something I am focused on. The citizenship certificate means that I can have a Croatian passport, which is ultimately Croatian. (TG-3-23M)

Several (FG-CTL-F, FG-CTL-F1, TG-3-3, TG-3-13, TG-SA-2, TG-SA-3, TG-3-21, TG-3-25) participants, including, naturally, political representatives, linked Croatian citizenship to voting as another opportunity to utilize the passport to claim recognition. One participant framed it precisely “I vote in Croatian elections. There have recently been elections for the EU Parliament, and we went to Mostar to cast a vote, it was only organized in one place. Indeed, I vote – you should use whichever right you have” (TG-3-21). As Kasapović (Reference Kasapović2012) shows, since the quota of seats for non-residents in Croatian parliament had been defined independently of participation, the electoral mobilization efforts decreased. Previously, kin-state parties framed the participation as another opportunity to demonstrate belonging to the kin-state, and some participants, similarly to women in the previous quote, still utilize voting to claim recognition of their belonging to the kin-state by their co-ethnics in Croatia. For others, it is yet another signal that the inclusion of the community in Croatia has decreased.

Three (TG-3-01, TG-3-03, TG-03-23M) participants explicitly suggested how they utilize citizenship across the EU. Essentially, when traveling outside the region, they do not wish to be identified with BiH for its international outlook, as they perceive it, and the higher status they receive with Croatian documents. When you “come with a Croatian passport,” one participant said, “it is a sovereign state, it proved itself through the war. I am happy and proud to show my Croatian passport when I come to a German border control. Honestly, it would be embarrassing for me to show BiH’s passport where they could mock me: ‘Look at him.’ ” (TG-3-03). Another participant similarly reflected:

It is looked differently [at you] if you are a Croat because Croatia is a part of the EU. As soon as you are part of the EU, it is different. It is looked at differently across the EU if you are an EU citizen. There are certain standards the country needs to achieve and some culture. I worked in the NGO sector for a while, I attended over 50 seminars, and people who travelled confirmed to me that once you mention BiH, the first association is terrorism. (TG-3-01)

Contrary to the other participants, two participants specifically distinguished what the formal recognition citizenship implies from their subjective feelings and denied the apparent identity management opportunities that citizenship provides. While holding a Croatian passport, one participant stated how she “do[es] not have a problem with the identity,” and continued “it comes naturally to me what I am. It is clear to me, so I am more focused” on the other aspects of citizenship (TG-3-08). Another participant used his Australian citizenship to highlight the irrelevance of the citizenship in recognition of his belonging. He said “Australian?,” not really, “I have an Australian passport, but I am not Australian, I do not feel Australian” (TG-3-14).

Looking at the symbolic dimension of meanings Croats in Herzegovina ascribe to citizenship, the data suggest that citizenship fails to overcome boundaries between the communities from the two sides of the border in the long term. Croats in Herzegovina recognize the value of formal recognition of their belonging. They also utilize citizenship as a means of identity management. However, contrary to kin-state policy expectations, the participants primarily utilize citizenship to claim their belonging to Croatia by their co-ethnics in Croatia even almost three decades after the kin-state policy was introduced. They explain it by highlighting their perception of decreased inclusion across the kin-state, building on their experiences, discourses across the kin-state, and further strengthening of the border that separates them from the co-ethnics.

Instrumental Dimension of the Kin-State Citizenship

Harpaz (Reference Harpaz2019a) and Harpaz and Mateos (Reference Harpaz and Mateos2019) argue that the growing number of people strategically acquiring second citizenship is associated with the rise in instrumental attitudes toward nationality. Individuals expect the second citizenship to provide them with economic advantages, global mobility, a sense of security, or even higher social status. EU membership status provides all those advantages to Croats in Herzegovina.

All participants across the sample highlighted Croatian membership in the EU as the single most significant factor contributing to the value of citizenship. The membership expanded the opportunities available to Croats in Herzegovina, especially regarding travel, work, and status across the EU. At the same time, EU membership opportunities reassured participants that acquiring citizenship two decades ago was justified in the long term.

However, at the time of acquisition, the circumstances were very much different. The war in BiH was still ongoing, and the future of the home-state was still at risk. Thus, the instrumental value of citizenship at the time implied a sense of security from the immediate threat individuals were facing. In addition, many Croats who now live in Herzegovina were still refugees in Croatia or only recently returned to BiH. With such an experience and in this context, individuals acquired citizenship against an immediate threat. Therefore, I argue that we need to differentiate between the citizenship that protects against the immediate threat, that is, protective citizenship, from the citizenship that enhances existing opportunities and provides security against potential risks, that is, pragmatic citizenship. Both protective and pragmatic citizenship imply the instrumental value, but the dynamics of acquisition and meanings ascribed to each are substantially different.

First, the acquisition numbers for protective citizenship are significantly higher. Second, the acquisition of protective citizenship is not framed as a choice but as the only option against the immediate danger and material deprivation. Third, protective citizenship generates more robust ties between the individuals and the kin-state.

One participant explained precisely how the protective kin-state citizenship impacted on the meanings she ascribes to citizenship. She said, “During the war, we fled, and Croatia helped us, you could rely on that, we were genuinely grateful. It provides a sense of security; God forbid if there is a similar situation in the future” (TG-3-21). Another participant who lived throughout the war, building on her experience, emphasized how she thinks of citizenship in terms of “security - who knows what comes with the time” (TG-3-19). Even some younger participants, building on their understanding of the war, recognize citizenship as protection against the potential worsening of the situation. One participant suggested how recurring societal tensions contribute to “instability and one never knows what could trigger another war” (TG-3-06).

Kin-state citizenship, at the time, protected individuals against material deprivation, caused by the war, by ensuring access to social benefits in Croatia. Two participants explained how their household benefited during the 1990s from maternity allowance (TG-3-19, TG-2-20). War veterans also received substantial war-related benefits. However, in 2000, once the circumstances in BiH improved and Croatian governments implemented stricter residency rules, access to benefits became a matter of choice. Croats in Herzegovina had to choose a residency in either Croatia or BiH, which led one participant (FG-CTL-F2) to claim that citizenship, at this point in time, lost its appeal and only created tensions. In the same year that this policy was introduced, 20,560 people stopped receiving contributions from Croatia (MF 2000, 46). War veterans from the focus group described the legal process many veterans initiated to get their pension entitlements back, explaining “we do not have any high expectations from Croatia, we only claim our pensions and health insurance” (FG-WV-M). Today, only 6,780 people receive a pension from Croatia (HZMO 2018, 111).

From 2000 onward, the type of opportunities citizenship provided changed significantly. Citizenship could only enhance existing opportunities. Some participants still recognize citizenship as an “insurance policy” (TG-3-19). However, the insurance policy, rather than it being used against an immediate threat, now only protects them against potential future risks. Altan-Olcay and Balta (Reference Altan-Olcay and Balta2020) and Harpaz (Reference Harpaz2019a, 98) established similar patterns in the case of the US and the EU citizenship acquisition from eligible individuals in Turkey and Israel. Since 2000, the decision to acquire Croatian citizenship or strategically utilize it was subject to consideration and weighing all the risks and benefits. Essentially, it was a pragmatic decision for Croats in Herzegovina to acquire or utilize citizenship.

The insurance policy argument periodically appears in headlines across Croatia and BiH when the prosecuted individuals in one country move to the other country in expectation of a sentence. Those individuals pragmatically use citizenship to avoid justice, despite efforts by Croatia and BiH to circumvent such attempts (Primorac, Buhovac, and Pilić Reference Primorac, Buhovac and Pilić2020). When this opportunity is used by wealthy, publicly exposed, and well-organized lawbreakers, it usually appears in headlines and, consequently, negatively portrays all dual citizenship holders.

For other people, pragmatic citizenship includes access to social benefits and services across Croatia and other support measures that Croatia directs toward the Croat community in Herzegovina. In a focus group discussion, participants outlined ways in which individuals can benefit from citizenship:

F2: It wouldn’t be good for us today had it not been for Croatia. Croatia helps us a lot.

F1: Croatia gave us more than BiH.

M: [Croatia] also supports culture.

F1: It supports war veterans financially.

M: Income from Croatia ensures one’s existence. Those who lost their lives or who were wounded get compensated, their status is recognized.

F2: … I have a pension [in Croatia], and I remain there. (FG-CTL).

In another focus group, two students emphasized the opportunity to keep Croatian health insurance, even if it is against the residency policy, but in case of anything more serious, they both suggested they would go to Croatia (FG-STD-M5, FG-STD-F2). Other participants also recognized the importance of health insurance and claimed that the Croatian health system is advanced compared with BiH’s (TG-3-12, TG-3-16, TG-3-19, TG-3-20, TG-MST-2). “I was taken by ambulance to Split, and they saved my life,” one participant explained (TG-MST-2). Another suggested that some people he knows kept the double residence “to feel safe if they needed medical assistance” (TG-3-16). Other participants highlighted Croatia’s financial help to different institutions, the opportunity to study in Croatia, or scholarships that students can receive (TG-3-06, TG-3-13, TG-3-11, TG-3-15, TG-2-MST-3, TG-3-6, TG-3-8, TG-3-24F, FG-CTL-F).

Finally, the most significant aspect of the pragmatic dimension of citizenship is related to the rights and opportunities related to EU status. The opportunities are framed well beyond the preferential treatment at the border and include the opportunity to work, travel, and study across the EU. All research participants highlighted the opportunities arising from EU citizenship, and this was even the case for the one research participant who did not hold Croatian citizenship. He semi-sarcastically insinuated he “is afraid to travel abroad” because he “might never return” when asked about the citizenship acquisition. His parents try to convince him to “sort out the papers, just to escape, should the situation require,” but he refuses (TG-3-17). Another young participant in Čapljina wishes to never leave Herzegovina, where she studied, but “just in case” she decided ‘to apply for formal diploma recognition in Croatia, should she “ever leave the country to have the papers clear” (TG-3-24-F2).

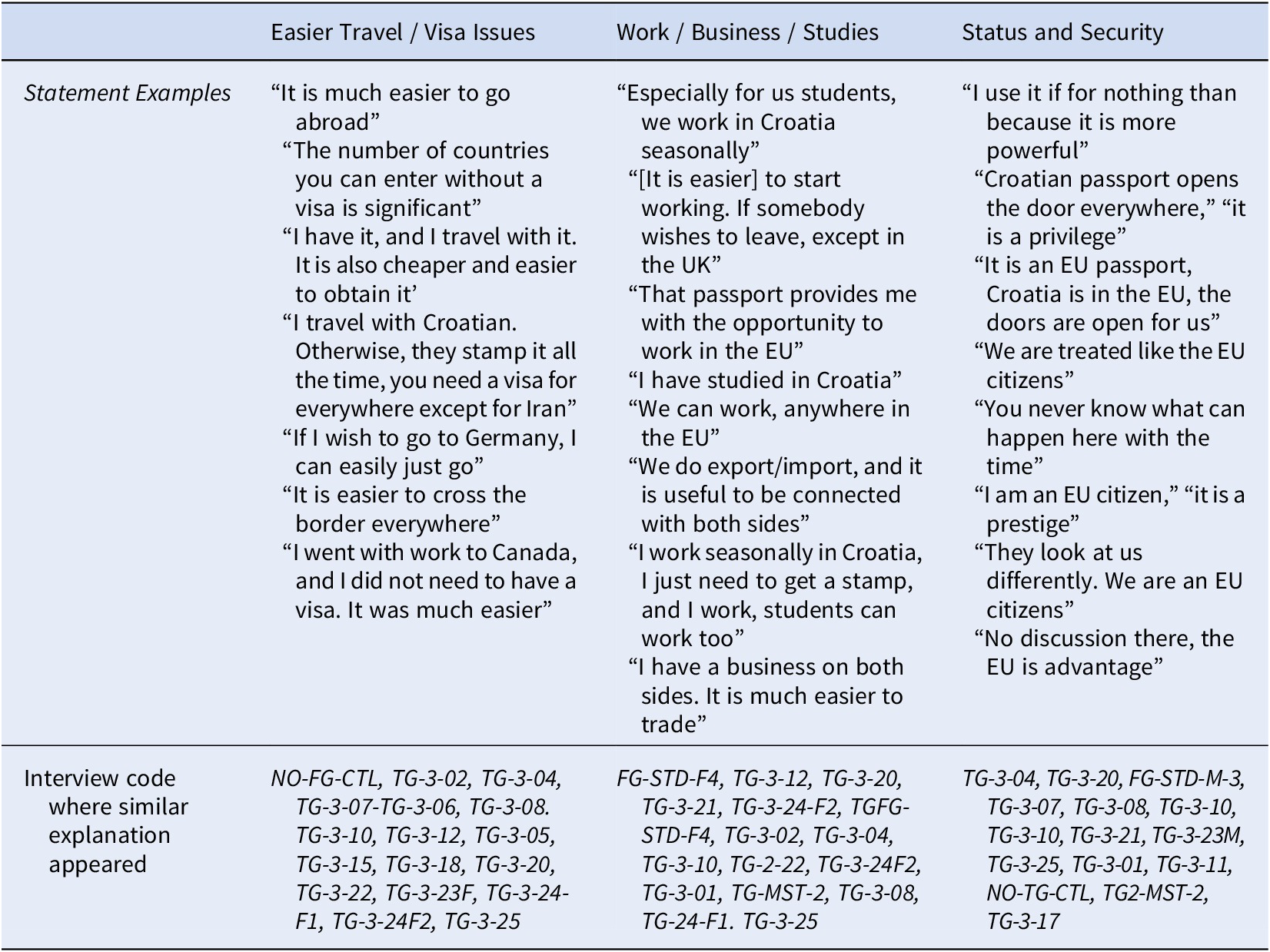

Below, in Table 1, additional examples of how participants reflect on opportunities attached to Croatian citizenship concerning the EU are outlined. All participants who discussed citizenship, even those who denied citizenship as a formal recognition of belonging, recognize the value of Croatian citizenship. Through the opportunities attached to citizenship, the kin-state expands the influence and captures more members of the transborder community. Furthermore, the status attached to Croatian citizenship across the EU generate recurring competing claims among transborder community members between the kin-state and home-state, in which the kin-state takes precedence for the opportunities it ensures. In almost all of the highlighted examples, research participants directly compared the opportunities each citizenship offers.

Table 1. Examples of Interview Reflections Capturing the EU Opportunities and the Interviews in which Similar Examples Appeared (some participants expressed all three categories of opportunities)

Some individuals illustrate the value of citizenship building on the experiences of individuals from BiH who do not have the opportunity to acquire EU citizenship (TG-3-01, TG-3-02, TG-3-06, TG-3-08, TG-3-11, TG-3-15, TG-3-21, TG-3-25). One participant elaborated that “I am very grateful for having Croatian citizenship alongside BiH’s. My colleague has wanted to work in Germany for over a year now. However, the procedure is long. He went several times to a visa interview in Sarajevo. The expenses are high, and it requires a lot of effort, while he cannot be sure if he will get the work permit and if all the expenses will pay off” (TG-3-02). “My friends often tell me,” another participant said, “lucky you for having [an EU] citizenship, If I had it, I would have left long ago.” (TG-3-08). Others express more generalized assumptions such as “my friends are jealous” (TG-3-25), “Others cannot leave that easily” (TG-3-01), or “They always tell us how lucky we are, we can always leave for Europe” (TG-3-11).

A woman (TG-3-21) who occasionally works in Croatia, witnessed how the number of people who used to work in Croatia seasonally, like her, and hold only BiH citizenship decreased once Croatia joined the EU: “They used to go with us,” she said, “but it is stricter now, those who do not hold [Croatian] citizenship cannot join us. They can, but only if they have the paperwork,” a work permit which is hard to obtain.

In a focus group with war veterans, who primarily think of citizenship as recognition of ethnic attachments and war contributions, participants strongly disapproved of cases where a member of another ethnic community obtained citizenship by claiming Croatian heritage. However, in a less disapproving and more understanding way, another participant emphasized how others wish to obtain Croatian citizenship for the opportunities it offers:

I often get proposed, in a witty manner, just for my Croatian citizenship. But it is not Croatian citizenship that matters; it is EU citizenship that matters. Croatia is privileged for the EU status. When you think about Serb people in BiH, they hold Serbian citizenship, but it does not mean a lot, except for one’s pride. I also know a lot of people who are not Croat, they do not declare themselves as Croats, not to say that they do not even feel as Croats, but they have Croatian papers and the passport, it is another interesting phenomenon (TG-3-25).

The case of Croats from Herzegovina shows how kin-state citizenship can enhance opportunities available to citizenship holders. However, during the 1990s, the opportunities protected the citizenship holders from immediate threats and material deprivation caused by the war. This contributed significantly to en masse acquisition, which appeared necessary and as the only available option. Only once the circumstances in BiH improved, citizenship gained pragmatic value. Since 2000, individuals have ascribed pragmatic meanings to citizenship, especially concerning access to social services and benefits. From this point onward, individuals could weigh the advantages and disadvantages of citizenship and align the meanings they ascribe to citizenship accordingly. Once Croatia joined the EU, the pragmatic value of citizenship increased significantly, including extensive work and travel opportunities and a higher status worldwide.

The Legitimate or Legal Dimension of Citizenship

Building on the case of Moldova, Knott (Reference Knott2019) introduced the legitimacy dimension. She showed how individuals claim citizenship as something normal, natural, and as a right. Rather than explaining citizenship through identity considerations or pragmatic reasoning, individuals claim it as a right they deserve, as a legitimate compensation for remaining in another state.

However, compensation claims for Croats in Herzegovina primarily capture the contributions the community made during the war in Croatia. The most explicit in expressing such claims are participants who fought the war. This is expected as these people feel they jeopardized life for Croatia – either by fighting in Croatia or BiH. Despite the recognition that war unfolded in BiH, participants argued that the Herzegovinian contribution was crucial to prevent Serb forces from merging all the territories they claimed during the war.

Furthermore, their ultimate loyalty lay with Franjo Tuđman, a wartime Croatian president, who ensured appropriate and deserving contributions according to a local political representative:

Tuđman and minister Šušak [Croatian Defence Minister at the time] appreciated the fact that Croats from Herzegovina were among the first, alongside other Croats, willing to engage, defend and die for Croatia. They compensated our contributions (TG-MST-2).

War veterans expressed similar thoughts. However, as seen in the previous part, they are frustrated with seemingly undeserving people who acquired Croatian citizenship. They are partly frustrated because such awarding of citizenship departs from their depiction of citizenship as a reward, compensation, and a right, which rectifies the sacrifices and loss they experienced in the war. They named people who fought against Croats in BiH but still acquired Croatian citizenship (because they could prove Croatian ancestry or had declared themselves as Croats within Yugoslavia). In contrast, “people who were in Croatian forces (HVO), Serbs and Muslims, who were with us the whole time - do not hold citizenship. They cannot acquire it … When it was easier to get it, somebody should have offered it to them for the contributions they made. They were four years in HVO! These things should be addressed! (FG WV).

Other research participants, including those who did not participate in the war, claimed citizenship as legitimate compensation. It was suggested, for example, that people “fought the war to be with Croatia, and they left” them in BiH “to deal with Muslims and to prevent the establishment of a Muslim country here” (NO-FG-CTL) or “we have it, but do not have it – Croatia is our homeland, it is” (TG-3-18). “Half of us went to war because we thought we would merge [with Croatia]” (TG-3-11) another participant stated when he reflected on citizenship. Overall, he would have wished more to be in Croatia than only to have citizenship. Another participant suggested that “Homeland war [which for Herzegovinians includes the war in BiH, while in Croatia alternative discourses exist] was fought for Croatia, and that attachment exists, and the help from Croatia toward us and those who fought is normal” (TG-3-22). One participant went further back in history to show how since long ago, Croats from Herzegovina supported Croatia, and all the people are “aware of their Croat nationality, more than people in Croatia,” which in his opinion, suggests that they deserve citizenship (TG-3-10).

Unlike their older counterparts, younger participants are not focused on compensation claims. They still consider citizenship as normal and natural, but rather than framing it as legitimate compensation, they simply think of it as a legal entitlement (FG-STD-M3, FG-STD-F3, FG-STD-M2, TG-3-02, TG-3-03, TG-3-04, TG-3-06, TG-3-07, TG-3-08, TG-3-15, TG-3-16, TG-3-19). In that way, they also distance themselves from the controversies surrounding the kin-state policy. For example, one participant explained, “I did not ask for it, there was an opportunity, so I took it, I mean, I feel grateful, but I did not ask for it, nor do I expect anything because of it” (TG-3-04). Similar to others, for her, citizenship is a legal entitlement. “I always had dual citizenship because I am entitled” (TG-3-06), another participant said. Another focus group participant similarly established how “[he] had the opportunity [to take it] so why not have it” (FG-STD-M6).

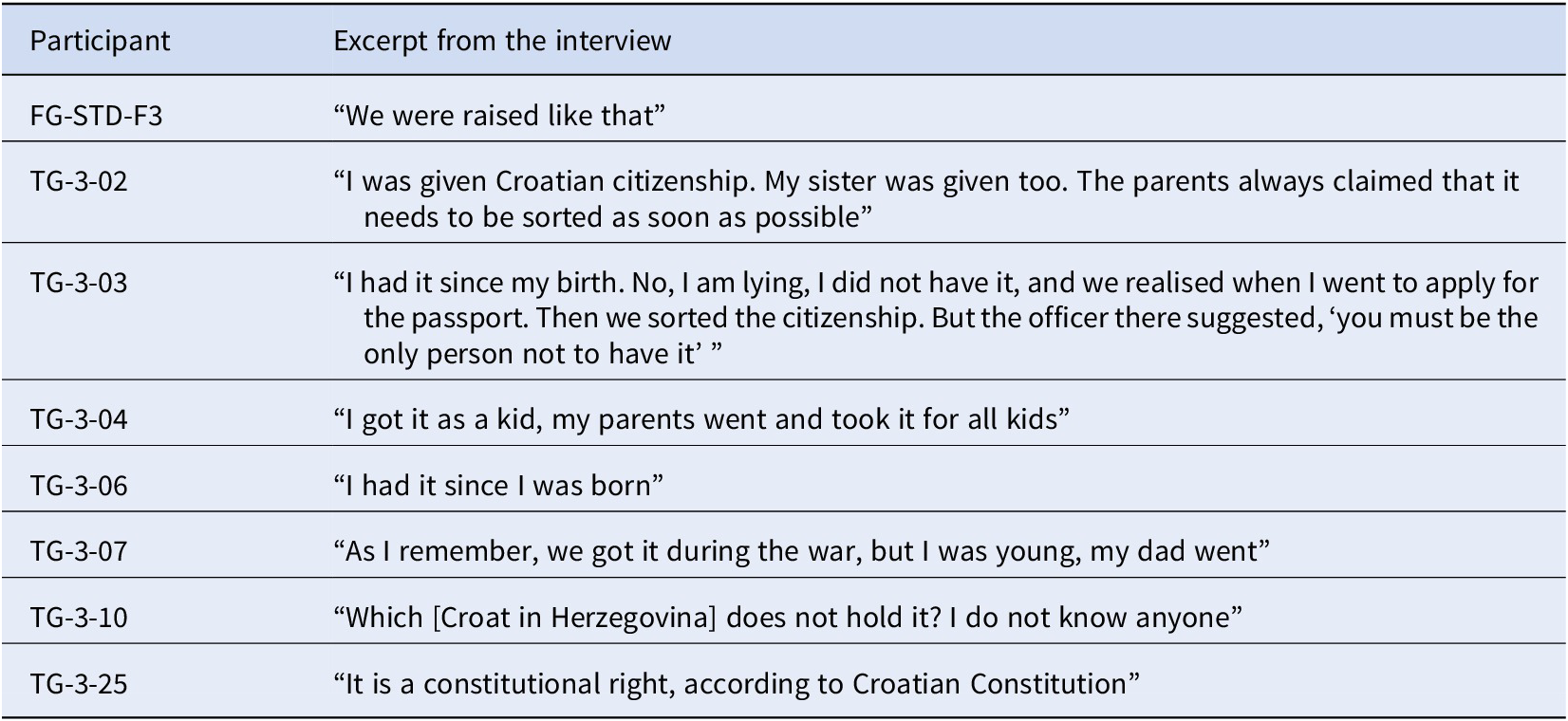

Most of these participants acquired citizenship when they were born, which remains a common practice, especially after Croatia became a part of the EU. It is normal to hold Croatian citizenship to the point where one individual even claimed that he does not hold the BiH’s citizenship, which is almost impossible, but it shows which citizenship is considered important (FG-STD-3). Some excerpts outlining how participants were born into citizenship, and how common the practice is, are highlighted in Table 2.

Table 2. Interview Excerpts Focused on Early Age Citizenship Acquisition

The following excerpts illustrate how, even among younger people, most still find it normal and common to request citizenship straight away upon the birth of a child.

Yes, straight away, it is the first thing to do once the kid gets born, you send papers to Zagreb [Croatian capital]. Certificate request, passport request, ID request, then you go to Metković [Croatia, in the proximity of border] to sign everything. That is the first thing, alongside baptism … Where to take health insurance and all. That is typical (TG-3-16).

Acquisition of citizenship has become a routine process for community members. While older participants still claim it as a legitimate compensation and justify the acquisition based on it, younger participants find citizenship indisputable. For them, having kin-state citizenship is normal and natural, a consequence of the already institutionalized legal system, and they are not concerned over the circumstance that impacted such an institutional design in the first place. In that way, they also distance themselves from the controversies surrounding the policy. Therefore, through the legitimacy dimension and routinization of citizenship practice, it becomes clear how the individuals become embedded in the kin-state’s legal framework in the long term. Moreover, the routinization of citizenship practice extends the pool of individuals who acquire citizenship beyond those who identify with Croatia or pragmatically acquire citizenship.

Conclusion

The kin-state citizenship is the most controversial policy kin-states pursue. In recent years, scholars have shifted attention from the state and looked at the meanings individuals ascribe to kin-state citizenship. The main findings in the literature on kin-state citizenship suggest that individuals view citizenship as a formal recognition of previously held feelings of belonging and utilize it to claim the belonging, through opportunities it provides compared with opportunities the home-state provides and as compensation for the past injustices that split the ethnic community in the first place. However, previous research focused on real-time citizenship acquisition and the states that only recently implemented kin-state citizenship policies.

Building on the case of Croats from Herzegovina, this article looks at how the meanings individuals ascribe to citizenship change in the long term and how the change impacts their understanding of citizenship. It does so by focusing on each previously established dimension of citizenship: symbolic, instrumental, and legitimacy.

First, by exploring the symbolic dimension of meanings individuals ascribe to citizenship, the study has shown how their perception of the decreasing inclusion into the kin-state impacts individuals’ claims. Back in the 1990s, when citizenship was introduced, and their belonging to the kin-state was indisputable, Croats in Herzegovina utilized it primarily to distance themselves from the home-state. However, since the 2000s, perception of their inclusion into the kin-state decreased among Croats in Herzegovina as a consequence of, in their view, experiences of traveling to or living in Croatia, changing rhetoric toward them in Croatia, and further strengthening of the border between them and Croatia. In response, Croats in Herzegovina have primarily utilized citizenship to claim recognition of their belonging to the kin-state by their co-ethnics in Croatia.

Second, the case of Croats from Herzegovina shows that the type and extent of opportunities impact the meanings individuals ascribe to citizenship. Two types of opportunities generate different understandings of citizenship. First, during the 1990s, citizenship protected individuals against immediate threat and material deprivation and contributed to seeing citizenship as protective. Second, as the circumstances in BiH improved, citizenship only enhanced already existing opportunities, and individuals viewed it as pragmatic. Protective citizenship increases acquisition level and depicts kin-state citizenship as the only option available to avoid the threat and generates stronger ties with the kin-state. On the other side, pragmatic citizenship prompts different sets of meanings ascribed to citizenship. Pragmatic citizenship is underpinned by careful considerations of competing opportunities provided by the kin-state and home-state. Moreover, since Croatia joined the EU, the opportunities citizenship provided have expanded significantly. Thus, in addition to access to Croatia’s welfare state and labor market, Croats in Herzegovina gained ample opportunities across the EU, which impacted how they understand the instrumental value of citizenship.

Third, by looking at the legitimacy dimension, the case of Croats from Herzegovina shows how compensation claims include war contributions individuals made to defend the home-state. As a result, such claims generate stronger ties to the kin-state than claims of past injustices when the border split the community. Moreover, the case of Croats in Herzegovina demonstrates how routinization of citizenship acquisition replaces legitimate compensation claims with legal entitlement claims among younger Croats in Herzegovina. As a result, individuals can distance themselves from the controversies surrounding the policies, and the pool of people who acquire citizenship expands beyond those who would acquire citizenship only for symbolic or instrumental reasons.

These findings extend our understanding of kin-state citizenship by demonstrating how the meanings ascribed to citizenship change over time. Moreover, it tells us that citizenship, as a category of practice, is not fixed but subject to changing perceptions of inclusion into the kin-state, the type and the extent of opportunities the kin-state provides and the routinization of citizenship practice.

More broadly, the findings suggest that the overall perception of the kin-state policies among individuals targeted with the policy can change in the long term. That is because the individuals respond to policy changes by aligning the meanings they attach to the policy’s entitlements and by expressing their views on the policy through the practice of entitlements. Therefore, future research on the kin-state policies should look more closely at the interplay between state policies and the individual responses to the policies. In this way, we can precisely establish the impact each kin-state policy has on individuals and their understanding of citizenship and other categories of practice the kin-state policies challenge.

Financial Support

The University of Liverpool funded this research through the Graduate Teaching Fellowship Scheme.

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this article was presented at ASN Annual Conference 2021. I am grateful to Eleanor Knott, Michiel Piersma, Erika Harris, and two Anonymous Reviewers for their insightful comments on earlier drafts of this study. Most importantly, this study would not have been possible without the engagement of research participants. I hope that the presented contribution justifies their trust.

Disclosures

None.