1. Introduction

Discourse particles have been attested in a wide range of languages (see e.g. Zimmermann Reference Zimmermann, Portner, Maienborn and von Heusinger2011, Grosz to appear for overviews), and they display several properties that distinguish them from other word classes. The most important properties in the context of our paper are that (i) most of them have counterparts in other word classes that are identical in form, and (ii) they do not influence the truth-conditional meaning of the host sentence. There is a debate in the literature whether these non-truth-conditional meanings are really conventionally implicated (Kratzer Reference Kratzer1999, Potts Reference Potts2005, McCready Reference McCready2010, Gutzmann Reference Gutzmann2015) or truth-conditionally vacuous presupposition triggers (Egg & Zimmermann Reference Egg, Zimmermann, Guevara, Chernilovskaya and Nouwen2012, Grosz Reference Grosz, Grinsell, Baker, Thomas, Baglini and Keane2014a). In this paper, we will contribute to this debate with the analysis of two discourse particles in Catalan where the counterparts are focus markers in the form of both focus particles and focus adverbs.Footnote 2

Catalan syntax-discourse phenomena as well as related lexical items have already been investigated in great detail in the existing literature from a formal linguistics perspective (e.g. Castroviejo Reference Castroviejo2006, Villalba Reference Villalba2008, Mayol & Castroviejo Reference Mayol, Castroviejo, Riester and Solstad2009, Mayol & Clark Reference Mayol and Clark2010). However, to the best of our knowledge, there are very few studies that investigated Catalan discourse particles from a formal perspective so far, let alone their relationship with their focus-marker counterparts. Although it has already been pointed out that Catalan is a language with a rich inventory of discourse particles (e.g. Espinal Reference Espinal2011, Torrent Reference Torrent2011), the only detailed formal study on Catalan discourse particles is Rigau’s (Reference Rigau, Brugé, Cardinaletti, Giusti, Munaro and Poletto2012) syntactic work on the particle pla (roughly meaning ‘it’s sure’), which is restricted to certain north-eastern varieties of Catalan. We will show below that, interestingly, some Catalan focus markers can take on a meaning which qualifies as a kind of meaning that we observe for discourse particles in other languages.

Specifically, we first introduce and demonstrate in Section 2 below that the Catalan focus particle també ‘also’ and the focus adverb precisament ‘precisely’ both feature a discourse-particle interpretation, in addition to their focus-marker reading. In particular, the focus particle també can take on an expressive reading such that the speaker conveys a negative attitude towards the proposition by using també. The focus adverb precisament, on the other hand, can emphatically assert an (unexpected) identity of two values or arguments in two different propositions. In Section 3, we will account for our observations within a probabilistic argumentative framework and provide a detailed analysis of the semantics and discourse properties of both també and precisament. Given this analysis, we will then turn to cross-linguistic comparisons of similar particles in other languages, and we will also address the more general question of how clear the categorial distinction between focus markers and discourse particles can be drawn at all, given their close semantic relationship we are observing in this paper.Footnote 3

Before introducing the relevant data in the following section, we would like to add a cautionary note on what we can and cannot (or will not) provide in this paper that compares focus-marker with discourse-particle readings of certain elements. We will provide evidence (and analyses) for the claim that the semantic contribution in present-day Catalan of some focus markers is rather a discourse-particle interpretation—but we will not look into the diachronic connections between those readings. Such a historical investigation is beyond the scope of our paper. It is controversial to what extent the different readings of these elements can be historically derived from each other, and, if so, which reading is older (see Mosegaard Hansen & Strudsholm Reference Mosegaard Hansen and Strudsholm2008, Mosegaard Hansen Reference Mosegaard-Hansen2018 on possible historical scenarios in Romance). Our goal is more modest: We first want to establish (by means of formal semantic tools and cross-linguistic observations) that there are discourse-particle interpretations of focus markers in Catalan in the first place. With these qualifications in mind, let us now turn to the two cases that to our mind are particularly interesting in this regard.

2. The Catalan particles també and precisament

2.1. The additive focus particle també and the expression of negative attitude

Like many other languages, Catalan features an inventory of additives (for additive particles in a general cross-linguistic perspective, see Forker Reference Forker2016 and König Reference König, De Cesare and Andorno2017). In what follows, we will restrict ourselves to the additive particle també because in this case, as we will argue, we also observe a reading that is reminiscent of cases in other languages where additive particles can acquire a discourse-particle reading.

Additive particles presuppose that what is predicated of the focused constituent also holds for at least one alternative of such constituent (e.g. Karttunen & Peters Reference Karttunen, Peters, Choon-Kuy and Dinneen1979; Krifka Reference Krifka1998). In Catalan, focused constituents occupy the last position of the matrix clause (Vallduví Reference Vallduví1992). In (1a), també associates with the object and it presupposes that Núria plays some other instrument. In contrast, in (1b) the additive particle associates with the subject, which here appears postverbally, and it presupposes that someone other than Núria plays the piano.

As has been shown extensively for English too, additive particles such as també feature anaphoric requirements, which can be analyzed as presuppositional anaphoras. Consider prominent examples like the following (Kripke Reference Kripke2009: 373):

Kripke (Reference Kripke2009) has pointed out that too has an anaphoric requirement that when one uses the particle too, one refers to information that is present in what Kripke calls the ‘active context’ (see also Ruys Reference Ruys2015 for recent discussion). The type of presuppositional anaphora associated with additive particles requires that it must be salient in the context that a person other than Sam is having dinner in New York. Crucially, as Kripke (Reference Kripke2009) argues, although one can reasonably and safely assume that many people are having dinner in New York on any given night, an account merely proposing an existential presupposition would not be able to explain why (2) would be infelicitous without a salient alternative to the individual Sam in the active context.

Observe now that the Catalan particle també has discourse uses where it does not convey additivity and the respective presuppositional anaphoras mentioned above; rather, també in these cases adds an expressive meaning to the utterance in the sense of Potts (Reference Potts2007a). We will detail this meaning contribution in Section 3 below, but for now consider the following key example from Torrent (Reference Torrent2011: 106):

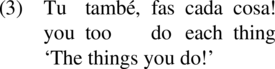

Example (3) does not convey that the addressee does something other than what is predicated in the sentence, but rather the speaker is expressing a negative emotion towards the actions of the addressee. The particle també in this expressive use frequently associates with sentence exclamations like (3) or wh-exclamatives such as (4); here, the speaker feels sorry for the addressee’s bad luck.

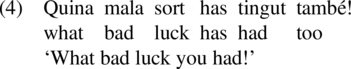

In contrast, this particle use of també is not felicitous when the speaker is not expressing negative surprise towards the proposition. In (5), també can only be interpreted as an additive particle: It is presupposed that other than having good luck, the addressee did something else (worked really hard to achieve something, for instance).

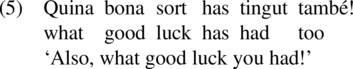

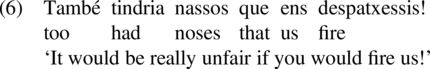

As already mentioned above, també often occurs not only in proper exclamatives (i.e. wh-exclamatives, see (4) above) but also in declarative clauses that can be characterized as sentence exclamations (according to Rett’s (Reference Rett2011) terminology), such as (6):

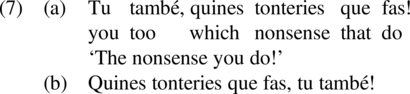

In wh-exclamatives like (7), també can modify a DP (very often a pronoun), and either precede or follow the exclamative; in both cases, we witness a clear prosodic break:

The particle també can also appear without a DP/pronoun, and in this case, there is a clear preference for using it clause-finally, where it takes scope over the whole proposition:

In sentence exclamations like (6) above, we observe similar placement options and preferences. In particular, també in its non-additive use occurs at the edge of the respective declarative clause: either clause-initially or clause-finally when modifying a pronoun, as in (9), or preferably clause-finally when it modifies the whole proposition, as in (10).

In the latter case, there is no prosodic break between també and the proposition it modifies.

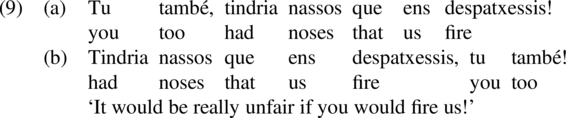

Although it is not our goal in this paper to analyze the syntax of this use of també, the data above seem to indicate that its base position is somewhere in the periphery of the clause. This is clearly evidenced by examples where the discourse and the additive particle també co-occur in one utterance, such as (11) – also again showing that we indeed can observe two very different meanings of també.

In those cases, the clause-medial occurrence of també can only receive the additive reading, while the non-additive version of també appears sentence-initially.

All in all, and regarding its syntax, Catalan non-additive també thus patterns with peripheral occurrences of discourse particles in Asian languages such as Cantonese (Matthews & Yip Reference Matthews and Yip2013), Mandarin (Paul & Pan Reference Paul and Pan2017), and Japanese (Kuwabara Reference Kuwabara2013), and with the placement of discourse particles at the outer edge of the clause that has been documented for the Indo-European language Romanian (Coniglio & Zegrean Reference Coniglio, Zegrean, Aelbrecht, Haegeman and Nye2012). Syntactically speaking, Catalan també seems to be another case where the clausal left periphery encodes discourse-oriented and/or attitudinal readings of an utterance.

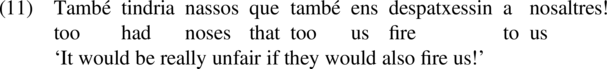

Finally, and turning to its semantic properties again, we have already observed above that també in its non-additive use expresses that the speaker has a negative attitude towards the proposition p. For ease of reference, let us therefore call this use of també ‘també expressive ’ and distinguish it from the focus marker ‘també additive ’. Crucially, també expressive is used in exclamation speech acts (as illustrated above), whose central feature is that they convey a presupposition of subjective veridicality such that the speaker believes that the propositional content is true (see Grimshaw Reference Grimshaw1979, Zanuttini & Portner Reference Zanuttini and Portner2003, Abels Reference Abels2010 for alternative accounts about the nature of this presupposition).Footnote 4 In other words, també expressive and its expression of negative attitude requires that it has to be in the Common Ground that p is true. To see this, note that utterances featuring també expressive cannot be used as answers to narrow-focus questions (12B), showing that they cannot provide the relevant new information.

However, we observe that the presupposition that the propositional content is true is not due to the use of també expressive , but rather is a feature of the exclamation speech act itself. That is, the utterance without també expressive is as bad as (12B) above when used as an answer to a question:

We thus hypothesize that while the negative attitude in (12B) is clearly due to també expressive , the presupposition that the speaker believes that the propositional content is true is not. Crucially, as we will argue in this paper, the expression of negative attitude is not the only meaning component conveyed by també expressive . In particular, we claim that there is another aspect that can be modelled according to ‘argumentative scales’ (see Winterstein Reference Winterstein, Bezhanishvili, Löbner, Schwabe and Spada2011, Winterstein et al. Reference Winterstein, Lai, Lee and Luk2018 and Section 3 below); these scales involve a consideration of the goal a speaker is aiming at in a discourse. In the case of també expressive , the speaker is not only expressing his negative attitude, but rather the utterance containing també expressive is interpreted as arguing for the goal ‘a negative attitude can be considered justified by both speaker and addressee’. We will turn to this point in detail in Section 3, but for now let us briefly illustrate this point.

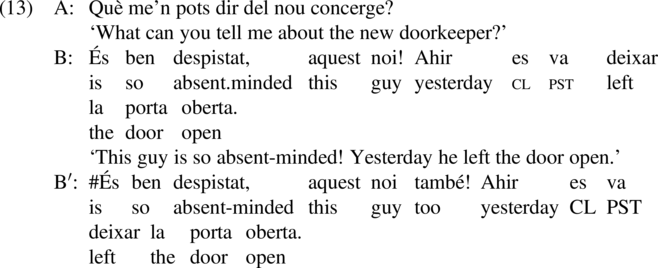

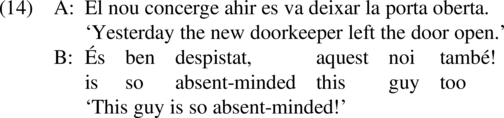

Example (13) below again contains a minimal pair of an exclamation with and without també expressive .

The version without també expressive (13B) is a felicitous response to the question posed by Speaker A, while the version with també expressive (13B′) is pragmatically deviant since in this case it is not clear in this broad-focus context whether there is any reason to hold a negative attitude. Once it is salient in the context for both speaker and addressee why one could have a negative attitude, the utterance becomes fully acceptable, as can be seen in (14):

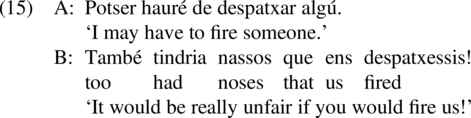

These examples indicate that both speaker and addressee must be able to relate to the speaker’s negative attitude in the sense that this attitude is not without cause in the respective context where també expressive is used. We hasten to add that this interpretation component of també expressive does not mean that the addressee also has to share the negative attitude expressed by the speaker. The addressee merely has to able to see that this negative attitude can be considered justified – in this way, també contributes a meaning that could also be considered evidential. Consider the following example:

In (15), it is clear that Speaker A does not need to share the negative attitude by Speaker B towards the surprising fact that Speaker B (and colleagues) will maybe be fired. Nevertheless, Speaker B can use també expressive in such a context because Speaker A is aware of the fact that Speaker B’s negative attitude is justified in the given context of surprisingly firing Speaker B (and colleagues).

All in all, the data discussed in this section have already indicated the following three meaning contributions that characterize the non-additive use of també, which we will analyze and thus further detail in Section 3 below:

-

• It is presupposed that the propositional content is true (not due to també expressive , but to its occurrence in exclamations).

-

• The speaker (and not necessarily also the addressee) holds a negative attitude.

-

• The interpretation of també expressive involves an argumentative component because the use of també expressive is interpreted as arguing for the goal ‘a negative attitude can be considered justified by both speaker and addressee’.

Given that també expressive thus contributes a negative attitude component, we can raise the question of what type of meaning this attitudinal component is. We hypothesize that it belongs to the class of conventional implicatures (CIs) just like other expressive items. One of the main tests to characterize expressive items is their behavior when embedded. According to Potts (Reference Potts2007a), expressive items are non-displaceable; that is, they predicate something about the utterance situation and cannot be used to talk about past events or express possibilities and cannot be semantically embedded (even if they are syntactically embedded).

For instance, the English expressive bastard cannot be interpreted in the scope of negation, as shown by the incongruence of the second sentence in (16): Negation only takes scope over the at-issue meaning (the proposition that Kresge is late for work) and does not apply to the attitude conveyed by bastard, which is left untouched (example from Potts Reference Potts2007a: 169):

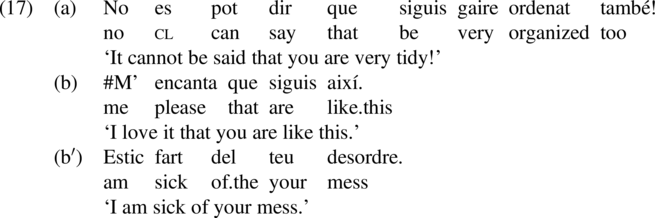

We can apply the same kind of test to també expressive . If the negative attitude conveyed by també expressive were truth-conditional, we would expect that it could be semantically embedded under negation, and (17a, b) should have a sensible reading, i.e. it should be interpreted as conveying that it is not the case that the speaker has a negative attitude towards the addressee (not) being organized. However, this is not a possible reading of (17), and this is why (17b) is incoherent.

In contrast, (17a, b′) is coherent since in (17a) també expressive is not semantically embedded under negation and conveys that the speaker has a negative attitude towards the fact that (it is not possible to say) the addressee is organized. We take the unacceptability of (17a, b) to show that the negative attitude of també expressive cannot be truth-conditional. It is, however, compatible with the attitudinal component being either a presupposition or a CI. To distinguish between the two possibilities, a test using the attitude verb ‘believe’ can be applied to our Catalan particle també expressive .

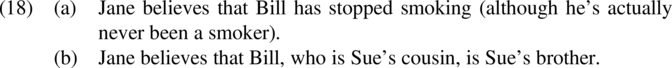

Presuppositions under ‘believe’ need not project, while CIs do project, as shown by the following examples from Tonhauser et al. (Reference Tonhauser, Beaver, Robert and Simons2013). The English example (18a) does not presuppose that Bill used to smoke (or that the speaker believes that Bill used to smoke), but that Jane believes Bill used to smoke. In Tonhauser et al.’s (Reference Tonhauser, Beaver, Robert and Simons2013) terminology, there is a Local Effect: The projective content of stopped smoking contributes to the local context of the embedding verb. In contrast, CIs project under believe, as shown in (18b). In (18b), the CI conveyed by the appositive noun phrase (i.e. the content that Bill is Sue’s cousin) projects and is attributed to the speaker and not to the subject of believe, who actually thinks that Bill is Sue’s brother).

Here, there is no Local Effect. If there were, the content of the appositive would contribute to the local context created by believe and the whole sentence would be contradictory (since two beliefs that cannot be true at the same time would be attributed to Jane).

Crucially, the particle també expressive displays the same behavior. Look at the following example:

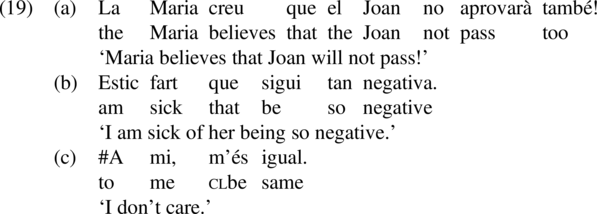

In (19a), the negative attitude conveyed by també expressive is really ‘anchored’ to the speech act of the speaker and can thus not be about the subject’s (= Maria’s) attitude, there is no Local Effect. This can be seen in the acceptable follow-up in (19b): The negative attitude is anchored to the speaker and not to Maria. If the negative attitude of també expressive in (19) had a Local Effect, we would expect a coherent meaning in which Mary has a negative attitude towards Joan’s not passing the exam which is not shared by the speaker. However, this reading is impossible, and the follow-up in (19c) is not coherent, since the negative attitude conveyed by també expressive is attributed to the speaker.

We can thus conclude that the expression of negative attitude is CI content, and together with its other meaning components (i.e. the presupposition that the propositional content is true and the argumentative scale), we will analyze this content in detail in Section 3.2 below. We will connect our findings to what we observe in the context of another Catalan particle: precisament (see the following Section 2.2). Among other things, we will show that while també expressive conventionally implicates the speaker’s negative attitude, precisament conveys an emotionally ‘neutral’ meaning. Interestingly, in other languages it is exactly the other way around; that is, while the cognates of també expressive are emotionally ‘neutral’, the cognates of precisament feature an expression of negative attitude. We will turn to these cross-linguistic comparisons in our final Section 4. But now let us take a detailed look at the other interesting particle: Catalan precisament.

2.2. The focus adverb precisament and the emphatic expression of identity

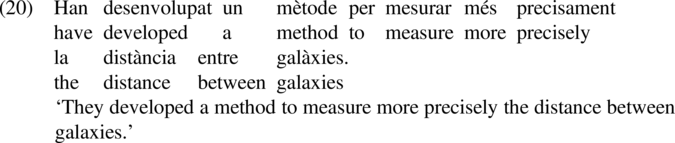

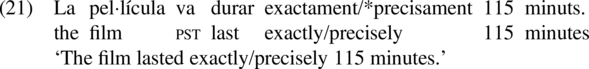

In this section, we will show that the Catalan adverb precisament ‘precisely’ has a variety of interpretations ranging from denoting manner to expressing discourse meanings. It can function as a VP-adverb with a manner interpretation, paraphrasable as ‘with precision’, as shown in (20). In contrast, it cannot be used as a degree adverb, meaning ‘exactly’, unlike its counterpart in English, as shown in (21).

A different use of precisament is as a focus adverb. As already mentioned above, in Catalan focused constituents occupy the last position of the matrix clause (see Vallduví Reference Vallduví1992). As can be seen in (22), precisament associates with the constituent in focus: la Maria in (22a) and el piano in (22b).

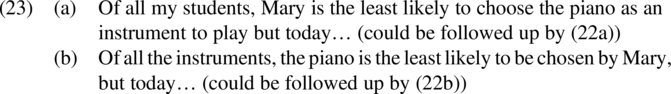

The focus-sensitivity of precisament can be demonstrated by the rather trivial fact that the two sentences in (22) cannot be used interchangeably. (22a), but not (22b), would be acceptable as a follow-up to (23a), while only (22b), and not (22a), would be fine in (23b):

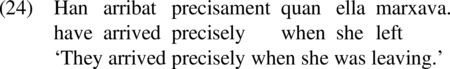

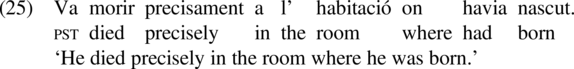

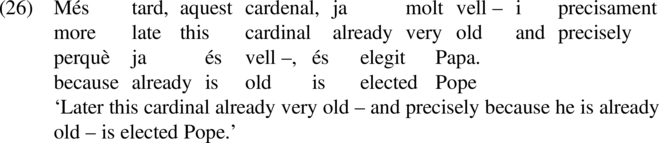

In its focus use, precisament often highlights the identity between two events or entities; this identity, which in its temporal reading can be conceptualized as a ‘coincidence’, can be temporal (24), locative (25), or causal (26), similar to the idiomatic expression ‘of all N’ in English (e.g. Krifka Reference Krifka1995: 227–229):

Let us look at the semantic import of this focus marker in more detail without going into the formal details at this point of the paper. Catalan precisament conveys that the expression in focus is also an argument in another salient proposition. For instance, in (24) the temporal argument of the event ‘He arrived at t’ has the same value of the temporal value of the event ‘She left at t’. The expression of this identity (in the temporal case: of this ‘coincidence’) often also conveys that it is unexpected; what precisament is thus doing is marking ‘a conflicting identity’ between the two arguments (see König Reference König and Abraham1991 on a relevant notion of ‘conflicting identity’). In other words, it is not usually the case that the arguments of these two propositions have the same identity. Accordingly, by using precisament, the speaker conveys that such an identity is noteworthy in the current discourse context. This can be seen even more clearly in some naturally-occurring examples retrieved from the web.Footnote 5

In (27), the adverb highlights that there is a noteworthy identity in that one character is seeking solace in another one despite having lived apart for many years.

In (28), the speaker points out that it is ironic that Turull will be the person to reconstruct the self-government, given that he greatly contributed to its destruction. In this case too, the identity of the relevant person is noteworthy (because in this case it is unexpected), and precisament is expressing this noteworthiness.

Finally, (29) can be understood as a reply to an addressee who is criticizing subsidies even though he is a beneficiary of such subsidies; this can be considered another case of an identity that is worth noting.

Given the above examples and paraphrases, the import of precisament seems somewhat reminiscent of scalar particles like even in English, at least in those cases where the emphatic assertion of an identity is embedded in a context of conflicting expectations and thus connected to a scale of likelihood (for an overview of further lexical means to convey scalar notions of emphasis, see Beltrama & Trotzke Reference Beltrama and Trotzke2019). However, precisament, in contrast to the additive even, does not presuppose that the predication holds for some other alternative. Crucially, in the current literature it is pointed out that the only three languages that feature particles expressing similar interpretations to Catalan precisament are German (ausgerechnet), Dutch (uitgerekend), and Hebrew (davka/דווקא); see König (Reference König, De Cesare and Andorno2017). If we take into account data like the above, we can now add Catalan to the class of languages that convey this kind of meaning by means of a single focus-marking element.Footnote 6

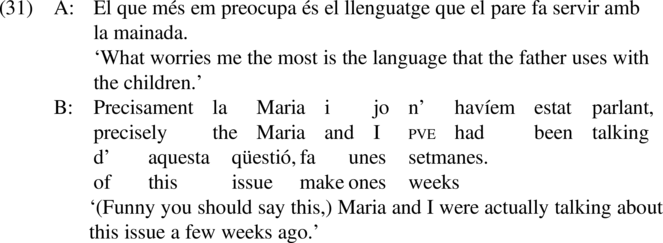

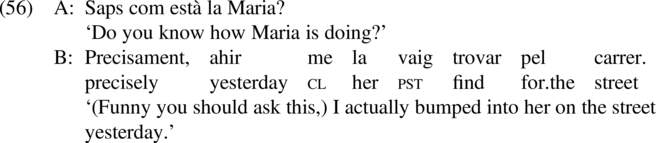

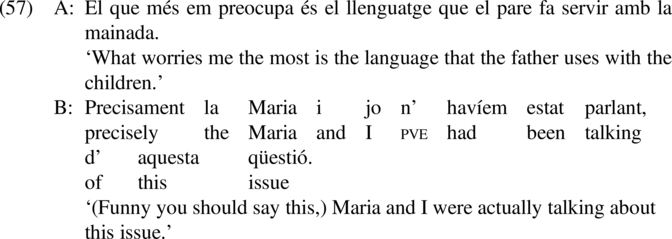

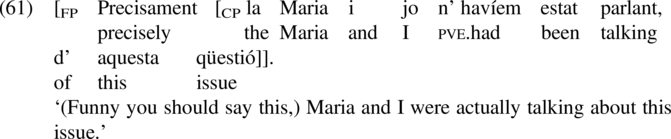

Now, precisament also has another discourse use, as shown in examples (30) and (31) below, in which its emphatic-identity reading refers to the respective sequence of speech acts in a dialogue. Here, precisament can serve to signal that there is a noteworthy coincidence between the previous utterance of the addressee and the current utterance of the speaker, similar to the expressions ‘funny you should ask/say this’ in English.

Specifically, in (30) the adverb signals that the speaker has a relevant answer for the addressee’s question given that he saw Mary yesterday. In (31), precisament signals that the speaker has something relevant to say about the issue raised by the addressee, and the fact that he has just talked about that particular issue with another person can be considered noteworthy. In these cases, the meaning of precisament is very similar to the use previously discussed, but with an important difference: It scopes over the whole speech act performed by the addressee in the preceding context. That is, in (31B) precisament does not emphasize that the speaker’s current speech act is identical to something what is said (i.e. there may not be anything surprising in uttering that he saw Mary yesterday), but that the previous question is surprisingly relevant for the speaker.Footnote 7

Let us take stock. The focus adverb precisament features anaphoric requirements in the form of specific presuppositions that must be met. Specifically, the use of precisament emphasizes the identity (or in many of our cases: the coincidence) of two values or arguments in two different propositions or of two consecutive speech acts. Note that some of our examples might suggest that the semantics of precisament contains a negative evaluative component. For instance, in (29) above the inference is that the addressee should not be talking about subsidies. However, this evaluative component is not always present; observe examples like the following:

We will thus consider this aspect of interpretation a conversational implicature and will not integrate it in our analysis. As we will also argue below, precisament is thus different from també expressive : In the case of també expressive , the evaluative component is indeed part of the lexical meaning and thus not triggered by a conversational implicature.

In sum, the data discussed in this section have demonstrated the following meaning contributions that characterize the Catalan focus marker precisament and that we will detail in Section 3 below:

-

• It conveys that there is (at least) an alternative q to the proposition p such that q it is not true.

-

• It emphasizes that there is either a value or an argument that is identical in two different propositions.

-

• Emphasizing this identity is used for expressing the overall interpretative effect that this identity is noteworthy.

Given all these illustrations of both Catalan també expressive and precisament, we are now in a position to turn to a formal analysis of these elements.

3. A formal analysis for Catalan discourse particles: A probabilistic-argumentation account

3.1. The probabilistic argumentative framework

To account for the discourse meanings of both també expressive and precisament in Sections 3.2 and 3.3 below, we will build on some previous work by Winterstein (Reference Winterstein, Bezhanishvili, Löbner, Schwabe and Spada2011, Reference Winterstein2012) and Winterstein et al. (Reference Winterstein, Lai, Lee and Luk2018), who use probabilistic semantics, following Merin (Reference Merin, Moss, Ginzburg and de Rijke1999), to capture the notion of argumentation (see Anscombre & Ducrot Reference Anscombre and Ducrot1977, Reference Anscombre and Ducrot1983) when investigating particle elements in different languages. Let us therefore briefly sketch some basics about this formal framework.

According to Merin (Reference Merin, Moss, Ginzburg and de Rijke1999), argumentation theory postulates that every utterance in a discourse is oriented towards an argumentative goal. In other words, speakers always use utterances to speak ‘to a point’. If an utterance argues for a goal, its orientation is positive regarding this goal; if it argues against it, it is negative regarding this goal. This notion of orientation is useful to explain a variety of discourse phenomena. For instance, observe the acceptability of an answer like in (33B); see Winterstein (Reference Winterstein2012) for a similar discussion.

The answer in (33B) is felicitous, although it is a logical contradiction: If the dinner is almost ready, it is not ready. Although ‘almost p’ entails ‘not p’, it argues for the same set of goals as p does (i.e. it preserves the argumentative profile of p and its orientation is positive); therefore, it is compatible with a positive answer; see Jayez & Tovena (Reference Jayez, Tovena, Bonami and Hofherr2008) for more extensive discussion.

Merin (Reference Merin, Moss, Ginzburg and de Rijke1999) casts argumentation as a probabilistic relation, such that a proposition p is an argument for a goal H iff asserting p raises the probability of H in the epistemic model, or, more formally, P(H|p) > P(H), where P is a probability measure. In addition, the strength of an argument can be captured by means of a probabilistic relevance function r such that p argues for H iff r(p, H) > 0.

This framework allows us to identify and account for the fact that some linguistic expressions are intrinsically argumentative, such as almost as illustrated above. Another well-known case is the connective but. In a sentence with but, the first conjunct argues for a goal, the second argues against it, the second one being more relevant than the first one. This is formalized in (34); see Winterstein (Reference Winterstein2012: 1875):

According to Winterstein (Reference Winterstein2012), the constraint in (34b) is why (35a) is interpreted as arguing against the goal ‘We should buy the ring’, while (35b) argues against ‘We should not buy the ring’:

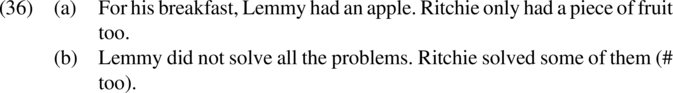

Winterstein (Reference Winterstein, Bezhanishvili, Löbner, Schwabe and Spada2011) argues also that the additive focus particle too is subject to some argumentation constraints. In particular, he is concerned with the following contrast:Footnote 8

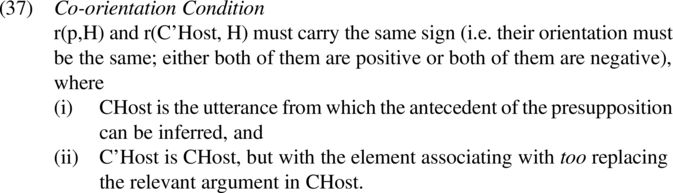

(36a) shows that the antecedent of the presupposition of too does not need to have been asserted, but it can be a conversational implicature of a previous sentence. In particular, the second sentence of (36a) presupposes that someone else had only a piece of fruit too, and this presupposition is satisfied by the conversational implicature of the first sentence (i.e. (36a) conversationally implicates that Lemmy didn’t have anything else apart from apple). (36b) also presents an implicated antecedent for the presupposition of too: The second sentence presupposes that someone else solved some of the problems, while the first sentence implicates that Lemmy solved some of the problems. Still, the presence of too renders (36b) infelicitous. In order to account for the infelicity, Winterstein (Reference Winterstein, Bezhanishvili, Löbner, Schwabe and Spada2011: 333) postulates the following constraint for the use of an additive particle like too:

For the case in (36a), we then obtain the following: p = Ritchie only had a piece of fruit; CHost = Lemmy had an apple; C’Host = Ritchie had an apple. If we take H to be ‘Ritchie only had a piece of fruit’ (so equivalent to p), we can see that both p and C’Host argue for it; that is, they both have a positive orientation. In other words, they satisfy the Co-orientation Condition. In contrast, for the example in (36b), we obtain the following: p = ‘Ritchie solved some of the problems’; CHost = ‘Lemmy did not solve all the problems’; C’Host = ‘Ritchie did not solve all the problems’. Since negation changes the sign of the orientation, p and C’Host will have opposite orientations (p argues for a goal H and C’Host argues against it) and, therefore, the Co-orientation Condition is not satisfied.Footnote 9 Note that the goal could be construed as equivalent to p, as we did in (36a), ‘Ritchie solved some of the problems’, or also more broadly, such as ‘Ritchie did well in the math test’.

Let us now see how we can apply these insights from argumentation theory to the analysis of també expressive (Section 3.2) and precisament (Section 3.3).

3.2. A probabilistic argumentative analysis for Catalan també

This section proposes an analysis for the two different interpretations of Catalan també (i.e. additive and non-additive, as illustrated in Section 2.1 above). The proposal is inspired by recent analyses of similar particles in other languages, in particular the analysis of the particle tim1 in Cantonese, which has both additive and mirative readings (see Winterstein et al. Reference Winterstein, Lai, Lee and Luk2018), the analysis of the Japanese evaluative particle yokumo in McCready (Reference McCready2010), and the analysis of German discourse particles proposed by Gutzmann (Reference Gutzmann2009). As will be shown shortly, també in both interpretations contributes meaning simultaneously at several dimensions of meaning: most notably, at the at-issue and the CI dimension (see Potts Reference Potts2005).

In a nutshell, at-issue meanings contribute the assertion of the utterance, which can be embedded under semantic operators and can be denied by another participant in the conversation.Footnote 10 In contrast, both CIs and presuppositions are harder to deny, and they project out of entailment-cancelling operators. The difference between presuppositions and CIs is, very roughly, that the former typically convey content shared in the Common Ground between speaker and hearer, whereas the latter contribute new information which is secondary to the main point (i.e. the assertion) that the speaker is making. We will treat both expressive meanings (needed for non-additive també) and argumentative constraints (needed for both additive and non-additive també) as CIs, following Winterstein et al. (Reference Winterstein, Lai, Lee and Luk2018) on this last point.

Given this conceptual background, we first analyze the focus particle també additive . According to what we have explained above for the very similar English additive too, també additive is an expression that simultaneously conveys at-issue and CI content. (38) represents its denotation, in which the ‘•’ operator joins at-issue and CI meanings (Potts Reference Potts2005, McCready Reference McCready2010):Footnote 11

in which

-

• x is the associate of també

-

• Q is the scope of també, the abstraction such that Q(x) = p, where p is the proposition també combines with

-

• Ψ(x) is the set of accessible alternatives of x

-

• Q(y)′ is akin to ‘C’Host’ in Winterstein (Reference Winterstein, Bezhanishvili, Löbner, Schwabe and Spada2011); i.e. the antecedent of the presupposition, but with the element associating with too replacing the relevant argument in Q(y)

-

• The function ‘co-oriented(p,q)’ is defined as r(p,H) and r(q,H) having the same orientation: Either they are both positive or they are both negative.

In other words, the focus marker també additive conveys the following three interpretative components:

-

(i) the assertion of Q(x), that is, of the proposition p

-

(ii) the presupposition that Q also holds of an alternative to xFootnote 12

-

(iii) the CI that Q(x) and Q(y)’ are co-oriented towards a goal H

The analysis in (38) represents that també additive introduces the presupposition (ii) and the CI in (iii), leaving its assertive at-issue content (i) unchanged.

In contrast to the additive focus-marker interpretation in (38), we propose that the non-additive reading of també with its expression of negative attitude does not involve a presupposition nor asserted content. Rather, it only involves CI content. We have already illustrated in Section 2.1 above why we postulate that its contributions are indeed CI contents only, and not presuppositions. The remaining question now is what semantic type exactly can be assigned to this content, and we believe that the answer to this question crucially relies on how we deal with the utterances també expressive occurs in: exclamations.

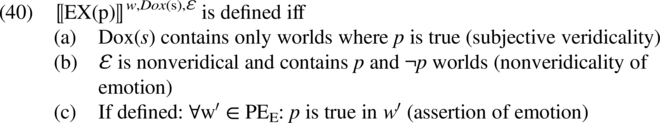

In Section 2.1 we have already indicated that també expressive can not only occur in wh-exclamatives, but also in exclamation speech acts more generally (e.g. also in declarative sentence exclamations like ‘This guy is so absent-minded!’ etc., see Catalan examples above). Given this situation, we follow Trotzke & Giannakidou (Reference Trotzke and Giannakidou2019) who unify the semantics of a variety of different exclamation types by claiming that the emotive stance of exclamation speech acts is actually an emotive assertion akin to assertions of sentences containing emotive predicates such as be amazed, be surprised in English, and that exclamation speech acts and such assertions have very similar truth conditions and presuppositions. We cannot discuss the details of their approach here, but let us briefly sketch how this works semantically.

Building on Giannakidou & Mari’s (Reference Giannakidou and Mari2020) proposal for emotive predicates, Trotzke & Giannakidou (Reference Trotzke and Giannakidou2019) assume that there is a set of worlds W ordered by the emotion (sentiment) S. W is partitioned into two equivalence classes of worlds. One is the set of worlds in which the attitude holder has the emotion and p is true. The other one is the set of worlds in which the attitude holder does not have the emotion and p is false. This partitioning allows us to define Positive-Extent-worlds (PE) for p; Ɛ refers to the emotive space:

The set P is the singleton set {p}. Accordingly, PEP contains all the worlds in which p is true. In PEP, the speaker has sentiment S. But not all worlds in Ɛ are PE worlds for p; Ɛ only partially supports p. PEP is a subset of Ɛ. The complement of PEP contains ¬p worlds. The semantics proposed here is reminiscent of the ‘Best ordering’ used for modals (Portner Reference Portner2009: Chapter 4); it is indeed a similar ordering function, only according to the present approach, the ordering source merely contains p. Figure 1 summarizes this constellation of worlds, based on the emotion ‘irritated’, which is gradable like all emotive attitudes are.

Figure 1 Emotion as a non-veridical space, from Giannakidou & Mari (Reference Giannakidou and Mari2020: 243).

Note: d = degree, w = world, p = proposition, Ɛ = emotive space, PEp = Positive-Extent-worlds for p

Given this semantic background, we can now formulate the denotation of an exclamation (EX), where Dox(s) is the belief state of the speaker, Ɛ is the emotive space, and PE refers to Positive-Extent-worlds for p (for more details, see Trotzke & Giannakidou Reference Trotzke and Giannakidou2019):

Let us now use this account of exclamation speech acts for our Catalan també expressive . Note that the emotive assertion of exclamations (‘I’m surprised/amazed at x’) is also present in the utterances containing també expressive . We thus conclude that també expressive does not cancel this assertion, but, just like també additive , conjoins at-issue (emotive assertion) and CI content (negative attitude + argumentative constraints) and is thus of type 〈ta,tc〉, according to the typing of such multidimensional items used by McCready (Reference McCready2010). That is, applying the denotation to a proposition φ yields ‘φ: ta • també expressive (φ): tc’. In other words, according to our analysis, també expressive applies after the exclamation operator EX.

Given these considerations, the CI content of també expressive can be represented as follows, where bad refers to a negative attitude on the part of the speaker (S) and highrel to the constraint of high relevance towards the speaker’s goal (for detailed decomposition of such a constraint, see Winterstein et al. Reference Winterstein, Lai, Lee and Luk2018: 27–28):

-

(i) the speaker holds a negative attitude towards ‘being surprised about x’ (the emotive assertion = p) and

-

(ii) a constraint stating that ‘being surprised about x’ is especially relevant to the argumentative goal ‘a negative attitude can be considered justified by both speaker and addressee’.

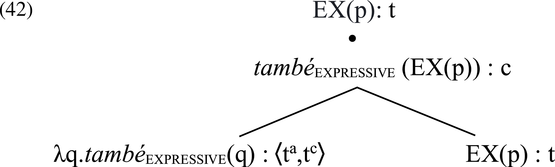

Note that according to our approach, both també additive and també expressive are hybrid expressions of type 〈ta,tc〉, the difference being that també additive , in addition to its assertive component, conventionally implicates that its assertion and presupposition are co-oriented towards a goal H, whereas també expressive conventionally implicates an expressive reading (negative attitude) and a related argumentative constraint, and this reading is conjoined with the emotive assertion of surprise expressed by the exclamation també expressive occurs in. Crucially, this assertion features at-issue content and can thus be targeted by truth-conditional denials just as declarative statements featuring emotive predicates can (e.g. A: I’m surprised that he is coming. B: No, you are not.). All in all, the composition of també expressive with the emotive assertion of surprise (EX(p)) can be represented as follows, which is very much reminiscent of what has been claimed for discourse particles in other languages (Gutzmann Reference Gutzmann2009); note that the proposition ‘being surprised about x’ is q in (42) in order to distinguish it from the descriptive content of the exclamation (p).

According to this multidimensional analysis, the truth-conditional content is passed up the tree unchanged and the conventionally implicated content sticks within the tree and thus cannot participate in any further semantic operations at the root node of the tree (i.e. cannot have any influence on the truth-conditional content of the utterance).

We thus conclude that the two different readings of Catalan també we have illustrated in Section 2 can be captured by the two different denotations given in (39) and (41) above. In particular, in contrast to the additive focus marker també, expressive també conventionally implicates that the speaker has a negative attitude towards the relevant proposition. With these claims and the application of the probabilistic-argumentation framework in mind, let us now turn to a detailed account of our second Catalan particle: precisament.

3.3. A probabilistic argumentative analysis for Catalan precisament

Let us now turn to the semantics of precisament in more detail. As we have already pointed out in Section 2.2 above, the import of precisament in examples such as (29), repeated here for convenience as (43), is (i) that the predication does not hold for some other focus alternative, (ii) that there is an identity between the expression in focus and the argument in some other salient proposition, and (iii) that this identity can be considered noteworthy.

As already mentioned in Section 2, one could hypothesize that what we see in examples like (43) is basically a likelihood-based presupposition that we also find in the literature on even. In our case, this would translate into something like ‘the referent of tu is the least likely person to talk about subsidies’. Note that not only additive even has been analyzed in terms of likelihood, but ‘of all X’ expressions as well (e.g. Krifka Reference Krifka1995).

However, some qualification is in order here, since some approaches have contested the claim that the scale is really based on likelihood or expectations. Consider the following example by Kay (Reference Kay1990: 84), illustrating that even can be used felicitously when the likelihood-based presupposition is not met:

In (44), it is explicitly mentioned that it was expected that Mary also beat the number three player, and thus p is marked as fulfilling rather than violating expectations. Nevertheless, even is perfectly fine in such a context. A related observation can be made for precisament in examples like the following:

The fact that Montse has been assigned to the French literature section of the library is not necessarily more unlikely than all other alternatives (say, the Japanese literature section, which may be smaller and, thus, less likely that one is assigned to work there). Still precisament is acceptable in (45) because it highlights the coincidence in this case between adoring (or hating) French literature and being assigned to work at the French literature section; accordingly, the prejacent of precisament is not surprising by itself.

On the other hand, Kay (Reference Kay1990: 83) has also pointed out examples like (46a), where even is infelicitous although the likelihood-based presupposition is met (see also Greenberg Reference Greenberg2016 for recent work on such scenarios). Note that other words, like still, that likewise emphasize the fact that p (here: working hard) can be regarded as violating expectations are felicitous in the same context (46b):

Given facts like the ones mentioned above, several characterizations other than likelihood have been suggested to capture all possible scenarios where scalar particles like even can occur felicitously (see Kay Reference Kay1990 and Herburger Reference Herburger2000). Recently, it has been suggested to replace concepts such as likelihood by a more abstract notion of a contextually supplied gradable property (see Greenberg Reference Greenberg2016, Reference Greenberg2018). We concur with the general approach articulated in this type of work, and we will thus use the general notion of ‘noteworthiness’ used by Chernilovskaya (Reference Chernilovskaya2014) and Nouwen & Chernilovskaya (Reference Nouwen and Chernilovskaya2015) in the context of exclamatives because we think that this notion is broad enough to capture all the uses we observe for Catalan precisament. Crucially, we claim that this meaning component is not encoded in the lexical semantics of precisament. Rather, precisament merely points to an identity between two values or arguments in two different propositions, thereby performing an ‘emphatic assertion of identity’, which has been proposed for similar particles (e.g. German ausgerechnet; see Section 4 below) in the semantics literature by König (Reference König and Abraham1991). However, the semantics of Catalan precisament conveys an argumentative constraint such that ‘an identity of x in p and q’ is especially relevant to the argumentative goal ‘the identity of x can be considered noteworthy’. Let us look at those separate meaning components in more detail.

According to our approach, what precisament essentially does in examples like (43) and all the other relevant cases in Section 2.2 above is to point out (i.e. shift the focus of the utterance to) the identity of two values or arguments in two different propositions. The particle can be used either in complex anaphoric situations like (43), or it can also occur in a sentence like (47), where the identity of an argument (here: ‘the people’), and not of a whole predicate, is emphatically asserted by using precisament:

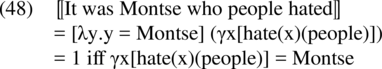

To approach this interpretation of ‘emphatic assertion of identity’ and thus the meaning of precisament in examples like (47), let us first adopt and sketch König’s (Reference König and Abraham1991) account of ‘emphatic assertion of identity’, which he formulated for the German particle ausgerechnet (which is very similar to precisament, see Section 4 below). König (Reference König and Abraham1991: 23) proposed to capture the semantics of the focus particle ausgerechnet by means of the collection operator γ, which has also been used to express identity relations in the context of English cleft constructions (see Atlas & Levinson Reference Atlas, Levinson and Cole1981: 52–53). In the cleft (48), γ forms a term phrase by combining with an open sentence and can be defined as in (49):

When we now turn to our example (47) above and the focus interpretation of precisament, we need a second argument (50) and also would like to say that (47) entails that whenever Montse helps someone, that individual is identical to someone who hates Montse; this is represented in (51):Footnote 13

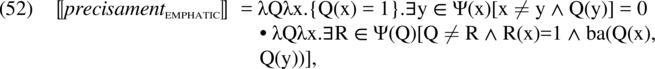

Given König’s (Reference König and Abraham1991) basic insights and his account of the relevant meaning components sketched above, we can now propose our analysis of the focus use of precisament in (52) (precisament emphatic henceforth), for which we adopt the argumentative view by Winterstein et al. (Reference Winterstein, Lai, Lee and Luk2018) again.

in which

-

• x is the associate of precisament,

-

• Q is the scope of també, the abstraction such that Q(x) = p, where p is the proposition precisament combines with,

-

• Ψ(x) is the set of alternatives of x and Ψ(Q) the set of alternatives to Q,

-

• ba expresses that Q(x) is a better argument than the alternative Q(y) for the argumentative goal H. Footnote 14

(52) represents that the Catalan precisament emphatic conveys meaning at the following separate meaning dimensions:

-

• It presupposes that the propositional content p is true.

-

• It asserts that there is (at least) an alternative y to x such that Q(y) it is not true.

-

• It conventionally implicates that (i) there is an alternative to R to Q such that R(x) is true and (ii) that Q(x) is a better argument (ba) for the argumentative goal than the alternative Q(y).

Note that according to our analysis, an utterance containing precisament emphatic is arguing for the goal ‘the identity of x can be considered noteworthy’. Accordingly, emphasizing that there is an identity between x in two different propositions Q(x) and R(x) argues for the goal ‘the identity of x can be considered noteworthy’.

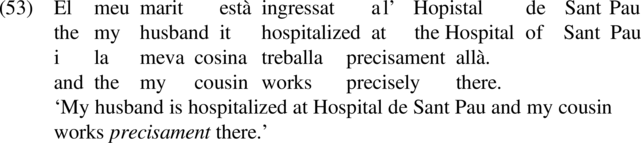

This analysis captures our data given in Section 2.2 above, and it can also account for differences like the following. (53) below is fully acceptable since it is easy to reconstruct the argumentative goal of noteworthiness in the case of a husband being in the same hospital where a cousin works.

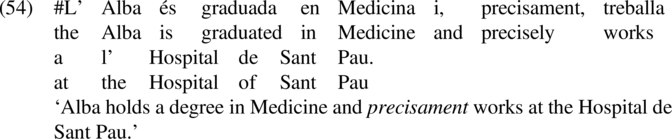

In contrast, precisament emphatic is pragmatically deviant in examples like (54) because it is not noteworthy at all that a person holds a degree in medicine and that s/he works in a particular hospital.

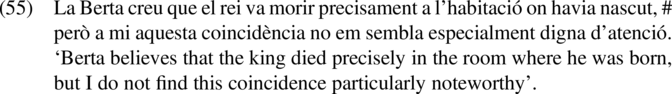

Moreover, just as we have shown for també expressive in Section 3.2 above, we can also demonstrate that the argumentative constraint of precisament emphatic must be attributed to the speaker, since it projects under the verb believe; observe the unacceptability of the second sentence in (55):

Given the analysis for precisament emphatic in (52) above, we can now turn back to our examples from Section 2.2 where the meaning of precisament emphatic is the same as in the analysis above, but where the particle operates at an illocutionary level. Look at (30) and (31) again, repeated here for convenience as (56) and (57):

In Section 2.2, we have already pointed out that precisament emphatic in those examples signals that the speaker has something relevant to say about the issue raised by the addressee, and the fact that the addressee has raised this particular issue can be considered noteworthy. In (56B) for instance, precisament emphatic does not signal that the speaker’s current speech act is conflicting with something (i.e. there may not be anything noteworthy in uttering that he saw Maria yesterday), but that the previous question is surprisingly relevant for the speaker.

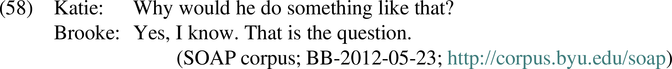

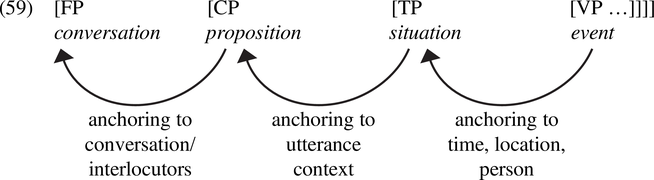

This use of precisament emphatic and its corresponding scope is reminiscent of particles in other languages that operate at the level of the so-called ‘conversation clause’ (FPconversation; see Wiltschko & Heim Reference Wiltschko, Heim, Kaltenböck, Keizer and Lohmann2016). Look at the following English corpus example from Wiltschko (Reference Wiltschko, Bailey and Sheehan2017: 254):

In (58), the wh-question can be answered by using polar ‘yes’ although Speaker B is not responding to Speaker A at the propositional level of CP. Rather, she expresses her agreement that Speaker A’s posing of the question is relevant; accordingly, her response operates at the conversational level. Without going into too much detail here, we can say that the basic idea of a syntactic approach distinguishing between these two different scopes is to account for readings like the one illustrated in (58) by postulating a functional projection above the CP level. This projection (FPconversation) encodes parts of utterance that are either referring to previous (as in our case) or future conversational moves (as in the case of ‘confirmationals’; see Wiltschko & Heim Reference Wiltschko, Heim, Kaltenböck, Keizer and Lohmann2016). We can illustrate this as follows:

With this approach to encoding conversation-related interpretations of discourse particles, response particles, and other elements in mind, we can now see how the two different scopes that precisament emphatic can take can be represented syntactically. On the one hand, we have discussed ‘propositional’ precisament emphatic like in example (60); on the other hand, we can now analyze (61) by postulating that precisament emphatic takes higher scope at the level of the conversational clause:

After having proposed our detailed analyses for the different readings of precisament emphatic above, we can now ask whether emphasis of the identity of two arguments in different propositions and the argumentative goal of conveying that p can be considered noteworthy may lend itself to further pragmatic effects that are not part of either the denotation or the specific scope-taking of precisament emphatic illustrated above.

In particular, it is obvious that in many of our examples featuring precisament emphatic (e.g. in our key example (43)), the speaker also expresses a negative attitude towards the proposition (further emphasized by continuations like Quina barra! ‘What a cheek!’ in (43)). However, we would like to claim that unlike in the case of the particle també expressive , this interpretation is not part of the denotation of precisament emphatic and thus totally context-dependent (compare the many other ‘non-negative’ examples given above). The particle precisament emphatic only conveys an evaluatively neutral meaning that we captured above in terms of emphatic assertion of identity and the denotation in (52).

Interestingly, when we now turn to languages other than Catalan, we can observe that it is exactly the other way around: While cognates of també expressive are emotionally ‘neutral’, the equivalents of precisament emphatic feature an expression of negative attitude. Let us look at some German data to illustrate this point and then conclude this paper by summarizing and highlighting some cross-linguistic implications.

4. Cross-linguistic implications and the thin line between focus markers and discourse particles

In this paper, we have looked at focus markers that can take on a discourse-particle reading. In particular, we have investigated Catalan discourse particles, which have not been studied from a formal semantics perspective so far. We demonstrated that the Catalan focus adverb precisament ‘precisely’ and the focus particle també ‘also’ feature interpretations that we identify as a type of meaning familiar from discourse particles in languages other than Catalan. After having outlined the basic distribution and interpretative effects of these particles in Section 2, we analyzed the semantics and pragmatics of Catalan precisament and també within a probabilistic argumentative framework in Section 3. We concluded that while també expressive is a particle that conveys a negative attitude on the part of the speaker, the particle precisament emphatic lexically conveys an emotionally neutral meaning only, which we captured in Section 3 in terms of ‘emphatic assertion of identity’.

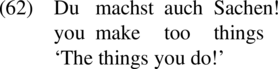

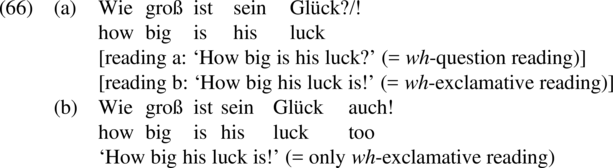

With these analyses in place, let us now turn to an interesting cross-linguistic comparison that suggests itself. German is a language where the additive focus particle auch ‘too’ has a discourse-particle reading as well, just like in the cases we have pointed out for Catalan above. While the standard contribution of auch as an additive focus particle has been analyzed in some depth (e.g. Reis & Rosengren Reference Reis and Rosengren1997; Büring & Hartmann Reference Büring and Hartmann2001; and many others), its discourse-particle use is acknowledged in the current literature, but it is only listed and mentioned as a side issue and has thus never been accounted for in detail (see e.g. Thurmair Reference Thurmair, Meibauer, Steinbach and Altmann2013). Crucially, when auch occurs in a sentence exclamation (62) or in a wh-exclamative (63), it functions just the same as Catalan també expressive :

Since this reading of auch in exclamation speech acts has been described as a clear case of a discourse-particle interpretation (Thurmair Reference Thurmair, Meibauer, Steinbach and Altmann2013: 642–643), we can therefore conclude that there clearly is a German counterpart to Catalan també expressive .Footnote 15

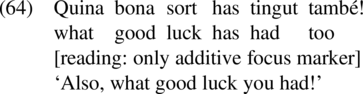

However, in contrast to Catalan també expressive , which, according to our analysis in Section 3.1, always features an expressive meaning in conveying a negative attitude, the German particle auch does not lexically encode such an attitude. (64) shows again that també expressive is not felicitous when the speaker is not expressing negative surprise towards the proposition. That is, in (64) també expressive can only be interpreted as an additive particle: It is presupposed that other than having good luck, the addressee did something else (worked really hard to achieve something, for instance).

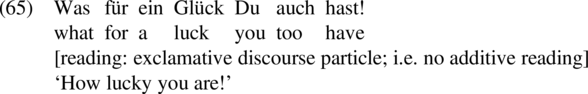

In contrast to Catalan també expressive , German auch is perfect in such a context (65):

We thus see that although both també expressive and auch can be characterized as particles occurring in exclamation speech acts, only Catalan també expressive is confined to contexts of negative surprise. The German particle auch does not add such an evaluative component. Rather, it additionally conveys the meaning of the intended exclamation reading of wh-configurations and thus serves as what Grosz (Reference Grosz2014b) has called communicative ‘cues’ in the context of optative clauses in German. In particular, the fact that the German language features a lot of syntactically ambiguous structures such as V2 wh-constructions (which can be either a question or an exclamation) correlates with the fact that this language features many discourse particles that together with other non-syntactic means such as intonation add up to the intended speech-act reading. That is, once auch is added to a structurally ambiguous wh-configuration such as (66a), the construction is disambiguated, and the reading is clearly an exclamation speech act (66b):

We would thus like to adopt Grosz’s (Reference Grosz2014b) proposal and claim that German auch in exclamation speech acts is accounted for by his ‘Utilize Cues’ framework, which does not posit a direct connection between the respective speech act (in our case: exclamation) and the respective particles in semantics, but rather assumes that there is an interaction established via general principles of communication. Crucially in our context, this also implies that auch in exclamations does not add any ‘extra’ meaning to the exclamation, in contrast to what we have shown for Catalan: Here, també expressive clearly adds a negative interpretation and could thus never occur in examples like German (66b) above, where the speaker can be happy about someone’s luck. In other words, German auch acts as a disambiguator in wh-exclamatives, given that German wh-exclamatives sometimes feature the same syntactic structure as wh-questions.

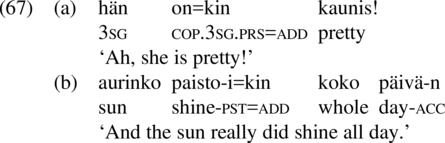

Broadening the cross-linguistic perspective further, we thus see that German seems to pattern more with Finnish than with Catalan because in Finnish the additive marker -kin (a clitic corresponding to English too) can also signal pleasant surprise or may just strengthen an exclamation, according to Karttunen (Reference Karttunen1975) and Karlsson (Reference Karlsson1999); examples from Forker (Reference Forker2016: 86):

Catalan, on the other hand, seems to pattern more with Mandarin Chinese, where additive markers are used to express a negative evaluation. In this language, for instance, the additive particle yĕ is used to express resignation or (tactful) criticism directed to the addressee, according to Hole (Reference Hole2004: 27). If our observations regarding the Catalan additive focus marker també expressive are on the right track, we may now add Catalan to this class of languages.Footnote 16

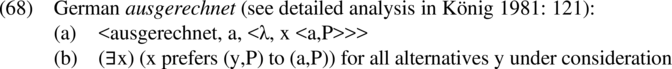

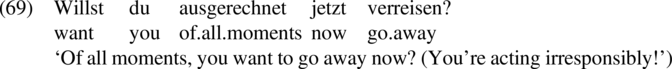

Turning back to our comparison of Catalan and German, it is interesting to see that German does not only feature a counterpart of també expressive in its inventory of discourse particles, but it also features an equivalent to precisament emphatic (already mentioned in Section 2.2): ausgerechnet (lit. ‘calculated’). Now, if we turn to this particle, we observe that in contrast to Catalan precisament emphatic , it has been claimed that the meaning of ausgerechnet is always evaluative and characterizes the focus associate as a non-optimal choice; that is, the speaker and/or hearer prefers any other situation than the present one (according to König Reference König, De Cesare and Andorno2017 and many others). Look at the classic analysis by König (Reference König, Eikmeyer and Rieser1981), which is using a categorial-grammar framework and assigns particles such as ausgerechnet a category schema where a in (68) is a category variable that stands for all categories that can occur as focus of ausgerechnet:

It is easy to bring out the evaluative component of the German counterpart of precisament emphatic . For instance, ausgerechnet turns a polar question into a biased question that obligatory conveys a negative evaluation of an affirmative answer. The following example from König (Reference König and Abraham1991: 20) makes this very clear:

We thus see that while the evaluative component of Catalan precisament emphatic is not always present and thus a conversational implicature (see our many data above), it is exactly the other way around in the case of the German counterpart ausgerechnet, following previous work by König (Reference König, Eikmeyer and Rieser1981, Reference König and Abraham1991). All in all, while the German cognate of també expressive (‘auch’) lacks an expressive specification, the counterpart of precisament emphatic (‘ausgerechnet’) seems to have it, and this is again in contrast to what we see in Catalan.

To conclude, our paper lends support to the central hypothesis that focus markers in many (even typologically less related) languages often have discourse-particle readings, and we hope that future work might detect and identify further discourse-particle elements in languages that are less known for discourse particles, like we have illustrated in this paper for Catalan. A question that has not been addressed by us in this paper is how the more ‘regular’ uses as focus markers and the discourse-particle uses of the particles are related. We have already highlighted at the outset of the paper that a diachronic investigation is beyond the scope of this paper. However, we have some final thoughts (or better: speculations) about that, which could be a starting point for future investigations: As for the element també, it is hard to see at first sight how també additive and també expressive are related, given the different analyses and denotations we are proposing in Section 3.2 above. Our hunch is that the ‘evidential’ component of també expressive is in a way additive just as the regular focus use of també additive is: By using també expressive , the speaker conveys that the reasons for having a negative attitude must be salient not only for him, but also for the hearer – and we could consider this the ‘additive’ component of també expressive . As for precisament, an explanation of how the readings of the manner adverb precisament ‘precisely/with precision’ and its emphatic focus use (precisament emphatic ) are related seems more obvious: In its emphatic use, the speaker highlights that two elements are the same, and this is noteworthy because one can say ‘with precision’ that they are the same and thus truly identical. After all, these are just speculations. But the detailed observations and semantic analyses in our paper might help future work to develop a full-fledged theory about the exact historical relations between the different readings and their respective developments.