Introduction

The US Constitution stands as one of the oldest yet least amended national constitutions in the world today, and while conventional wisdom has long held that this low amendment rate is largely attributable to the onerous amendment process outlined in Article V (Lutz Reference Lutz1994; but see Ginsburg and Melton Reference Ginsburg and Melton2015), some contemporary constitutional commentators argue that difficult amendment rules are not solely to blame. Footnote 1 Echoing Thomas Jefferson’s famous warning that citizens inevitably treat their constitutions “like the arc of the covenant, too sacred to be touched” (letter to Samuel Kercheval, July 12, 1816, in Jefferson Reference Jefferson and Ford1904-1905, 12:11–12), they suggest that a culture of “reverence” for the Constitution has left most Americans unwilling to seriously consider the possibility that it needs to be amended (Jackson Reference Jackson2015; Levinson Reference Levinson1990, Reference Levinson2006; but see Blake and Levinson Reference Blake and Levinson2016), despite the fact that many have grown dissatisfied with the system the Constitution establishes. Footnote 2 On this view, constitutional veneration can act as a sort of threshold psychological barrier to constitutional amendment.

The notion that the USA is unusual in the extent to which its citizens treat their national constitution with almost religious-like respect is nothing new, but Zink and Dawes’s (Reference Zink and Dawes2016) study marks one of the first attempts to examine the empirical plausibility of the claim that reverence for the Constitution biases individuals against constitutional amendment. They conducted a series of experiments designed to test respondents’ willingness to support several constitutional amendment proposals, ultimately finding that many individuals exhibit a specific bias in favor of the constitutional status quo that disposes them to reject the amendment proposals, even when accounting for alternative explanations such as individuals’ political and policy preferences, knowledge, and risk orientations. As Brown and Pope (Reference Brown and Pope2019, 1147) point out, however, Zink and Dawes’s findings essentially rest on inference: They design their experiments to control for likely alternative explanations and then infer the effects they observe are attributable to “constitutional veneration.” But their study does not include a measure of constitutional veneration, and thus, it does not clearly establish a direct link between individuals’ respect for the Constitution and their reluctance to support amendments to it.

We set out to test whether “veneration” for the Constitution – a sense of attachment to the Constitution that is substantially based on the document’s symbolic significance – translates into resistance to amending it. To do this, we refine and build on Zink and Dawes’s study by attempting to replicate their results on a representative sample of US adults through the 2016 Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES). Footnote 3 Importantly, whereas Zink and Dawes infer that individuals’ bias in favor of the constitutional status quo is attributable specifically to their attachment to the US Constitution, we use self-reported measures of respondents’ support for the Constitution to establish a direct link between individuals’ resistance to constitutional amendment and their attitudes about the Constitution. We also account for an alternative explanation that Zink and Dawes’s study did not: individuals’ tendency to rationalize their social and political systems (Jost, Banaji, and Nosek Reference Jost, Banaji and Nosek2004; Jost et al. Reference Jost, Liviatan, van der Toorn, Ledgerwood, Mandis-odza and Nosek2010; Kay and Jost Reference Kay and Jost2003), a tendency that offers an especially powerful explanation for why individuals may resist amending the Constitution and stick with the constitutional status quo, even when they would benefit from a proposed change (Blasi and Jost Reference Blasi and Jost2006). Finally, we conducted a follow-up study using Brown and Pope’s (Reference Brown and Pope2019) seven-question measure of constitutional respect to confirm that our results hold when using a different (and better) gauge of respondents’ feelings toward the Constitution.

Overall, we find that respect or “reverence” for the US Constitution can translate into resistance to amending it. Our results bolster and build on Zink and Dawes’s findings and show that, in addition to institutional factors, citizens’ veneration of the Constitution can act as a psychological obstacle to constitutional amendment. These results highlight an important extra-constitutional factor that can affect amendment difficulty.

Experiment 1

We conducted a version of Zink and Dawes’s (Reference Zink and Dawes2016, 541–48) experiment on a representative sample of adults on the post-election wave of the 2016 Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES) (N = 822). As in Zink and Dawes’s study, respondents were asked about their willingness to support two hypothetical proposals, one that would reinforce collective bargaining rights and another that would require a legislative supermajority to approve any proposed tax increases. Footnote 4 Respondents were randomly assigned to either the control or treatment condition where they were asked about both proposals in randomized order. The conditions differed only in that the questions in the control framed the issues as proposed changes to federal law while those in the treatment framed them as proposed amendments to the US Constitution. Complete question wording is included in the Appendix.

Our most basic expectation is that framing the proposals as constitutional amendments will significantly reduce support for them relative to the control questions emphasizing change to federal law. As with Zink and Dawes’s study, the experimental design controls for the possibility that any treatment effects we observe are reducible to status quo bias based on risk aversion or uncertainty (see Zink and Dawes Reference Zink and Dawes2016, 538–40, 545–48). Respondents who are biased against change per se should be as likely to resist changes to federal law as they are changes to the Constitution, holding the issue constant. The questions in both conditions also included language emphasizing that the proposals would not upset the policy status quo if approved. This language was intended to mitigate concern about unintended consequences and thus account for the possibility that some respondents may simply oppose using constitutional means to implement a policy, even one they prefer, because it is more difficult to reverse the change in the event it has unanticipated negative effects. To be clear, the questions explicitly present the proposals as changes to the legal or constitutional status quo. But those who harbor these concerns do not resist amending the Constitution because of a preference for the constitutional status quo per se, but rather because they worry about how amending the Constitution might affect the policy status quo. The additional language should allay these concerns. Footnote 5

To the extent we find greater opposition to the proposals in the treatment condition, then, it is likely in part due to the specific fact that the proposals involve constitutional change. In contrast with Zink and Dawes, however, we do not rest our interpretation of the results on inference. In the pre-election wave of CCES, we asked respondents about their views on how much, if at all, the Constitution should be changed to make it more relevant today. This question allows us to more directly test whether the treatment effects are attributable specifically to respondents’ attitudes about the Constitution. We expect our treatment to be strongest among those who believe the Constitution is a “document that works well today and does not need to be changed” compared to those who think the Constitution needs minor or major changes.

We acknowledge this measure is not ideal. As an initial matter, it seems entirely obvious that individuals who think the Constitution works just fine without any changes would be much less supportive of amending it. To this point, we note that, in principle, even those who think the Constitution works fine as it is should not necessarily oppose amending the Constitution, especially when they support the policy embodied in an amendment proposal. Holding the view that the Constitution works without any changes does not commit one to the view that it should not be changed. More generally, this “Constitution works” question arguably could capture respondents’ opinions about how well the Constitution performs as a practical governing instrument, which in turn would allow for an alternative explanation for our results: Instead of offering evidence that “reverence” for the Constitution biases individuals against amending it, our results demonstrate that respondents are making rational judgments about how amending the Constitution might affect its performance. This reading of the measure, however, attributes to individuals more considered attitudes about the Constitution than extant research suggests is plausible. Recent studies indicate that Americans overwhelmingly approve of the Constitution (Stephanopoulos and Versteeg Reference Stephanopoulos and Versteeg2016), despite knowing very little about it (Farkas, Johnson and Duffet Reference Farkas, Johnson and Duffet2002), and that individuals’ attitudes about and approval of the Constitution are stable and remain mostly unchanged by exposure to new information about its content or history (Brown and Pope Reference Brown and Pope2019). Footnote 6 Taken together, these studies suggest that attitudes about whether the Constitution “works” are mostly reflexive and likely do not reflect a careful, rational appraisal of its content or performance, which is why we contend the question is useful, if imperfect, proxy for constitutional veneration. To the extent respondents who think the Constitution works are much less supportive of amending the Constitution, it is likely due to a background attitude or feeling toward the Constitution rather than a considered judgment about how a specific amendment might affect how well the Constitution works. Nevertheless, we revisit this measure in Experiment 2, where we include a better gauge of respondents’ tendency to revere the Constitution.

Finally, our experiment also accounts for another likely alternative explanation Zink and Dawes did not address in their study. As Jost, Banaji and Nosek (Reference Jost, Banaji and Nosek2004) explain, many individuals are motivated to rationalize the political and social systems that most affect them – to emphasize their system’s virtues and downplay its vices – in part as a way of feeling better about their place within the societal status quo. System justification theory offers an especially powerful explanation for why individuals might resist social, political, and legal changes that they otherwise could benefit from (Blasi and Jost Reference Blasi and Jost2006), so it is important to control for this tendency. An individual who is prone to system justification might resist amending the Constitution for reasons that have little to do with the Constitution itself; instead, a bias in favor of the constitutional status quo may simply reflect the more fundamental inclination to justify one’s position within the political system as a way of coping with existing institutional arrangements that one feels powerless to change. To account for this possibility, we included on the pre-election survey a battery of questions that together measure the extent of individuals’ inclination to justify status quo political arrangements (Jost et al. Reference Jost, Liviatan, van der Toorn, Ledgerwood, Mandis-odza and Nosek2010). If the results we observe are explained by system justification rather than constitutional veneration, then we would expect the treatment effects to be significantly larger among those who score high on the system justification scale.

Experiment 1 results

The top panel of Table 1 presents the average treatment effects for both proposals based on the CESS study. Confirming Zink and Dawes’s finding that respondents are more reluctant to change the Constitution than ordinary federal law, framing the proposals as amendments to the US Constitution significantly reduces support for them (i.e., increases support for the status quo) relative to the corresponding control conditions. In addition, the treatment effect based on the CCES representative sample is very similar to the MTurk convenience sample (bottom panel) analyzed by Zink and Dawes (10 percentage points versus 14 percentage points). Footnote 7

Table 1 Average treatment effects for hypothetical propositions in the original Zink and Dawes experiment as well as the replications in the CCES and Lucid samples. Support for the status quo is coded as “0” if the respondent supported proposal and “1” if they opposed proposal. P-values are associated with two-tailed t-tests.

As Figure 1 indicates, the treatment effects are strongest among those who believe the Constitution “works well,” consistent with our expectations. Similarly, those who believe the Constitution “still works” but “needs minor changes” are less likely to support the amendment proposals. The effect sizes are smaller in magnitude, as expected for this group, although the treatment for the collective bargaining proposal does not quite achieve statistical significance (p = 0.07). We find no significant treatment effects among respondents who view the Constitution as “outdated” and in need of “major changes.” Footnote 8 This offers more direct evidence that the effects are not reducible to general status quo bias but rather are attributable specifically to respondents’ attitudes and/or feelings about the Constitution.

Figure 1 Treatment effects and 95% confidence intervals for the collective bargaining and 2/3 majority conditions among respondents feeling the constitution is “outdated and needs major changes,” needs some minor changes,” and “works well today still works and does not need to be changed.” Average support for the constitutional status quo within each group is presented in Appendix Table 1.

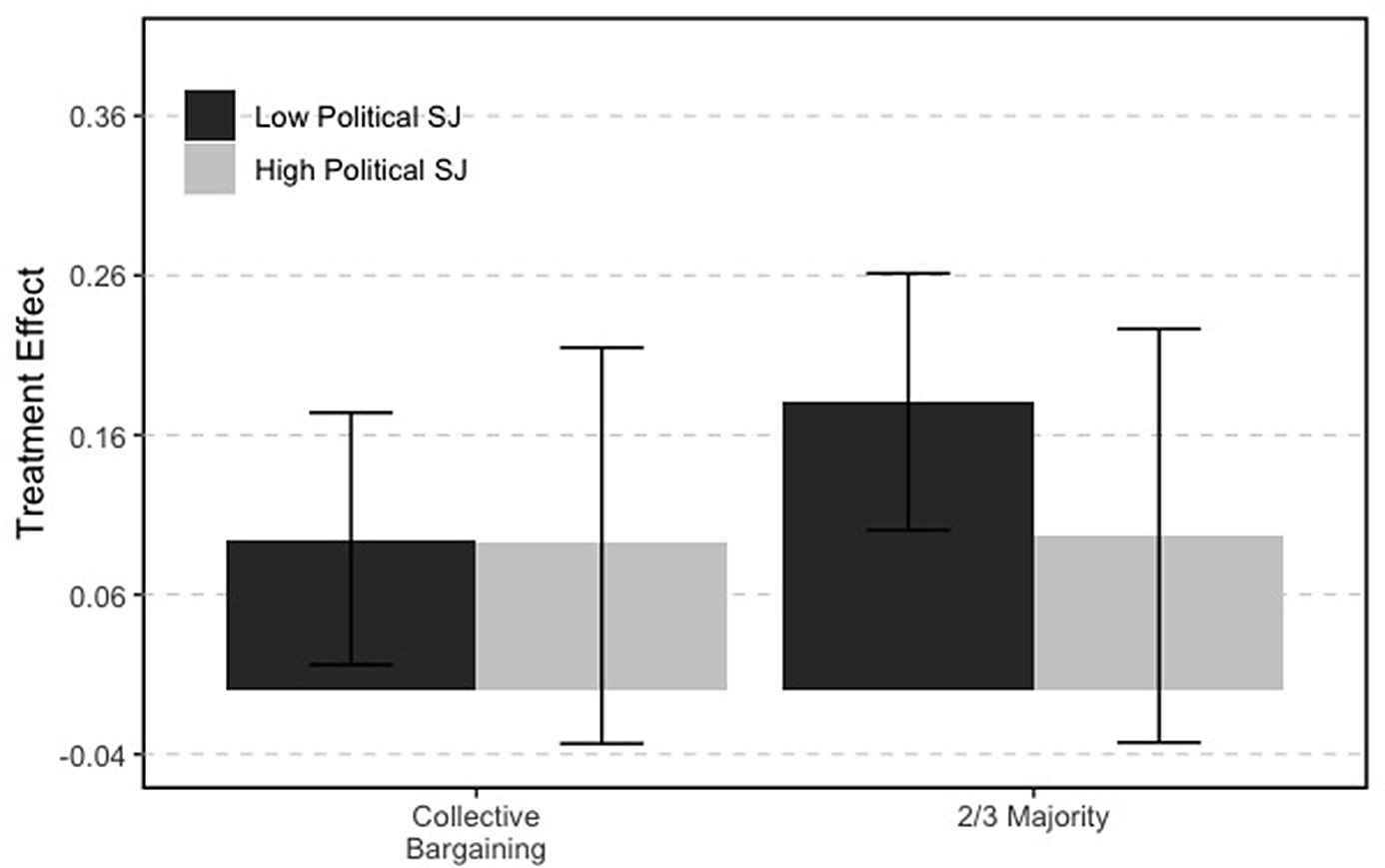

As the results presented in Figure 2 suggest, these effects are not driven by respondents’ more basic propensity to justify their sociopolitical systems. Because high system justifiers are more likely to prefer the status quo, we would expect our treatment effects to be much larger among those who score high on the political system justification measure. Footnote 9 But the effects do not significantly differ based on respondents’ level of support for the political system.

Figure 2 Treatment effects and 95% confidence intervals (associated with two-tailed t-tests) for the collective bargaining and 2/3 majority conditions among high and low political system justification respondents. Average support for the constitutional status quo within each group is presented in Appendix Table 3.

Experiment 2

We have argued that to the extent the treatment effects are higher among those respondents who think the Constitution works without changes, it offers strong evidence that something like constitutional veneration biases individuals against amending the Constitution. As we have suggested, however, the “Constitution works” question is an imperfect proxy for constitutional veneration. Among other things, the question may tap into other attitudes, such as respondents’ considered opinions about how well the Constitution performs as a governing instrument, that offer plausible alternative explanations for our results.

To address this difficulty, we ran a follow-up experiment in December 2020 on the survey respondent aggregator Lucid. Footnote 10 In total, we recruited 470 participants, but we restrict our analysis to the 336 respondents that successfully completed a Mock Vignette Check (Kane, Velez and Barabas, Reference Kane, Velez and Barabas2020). Footnote 11

Prior to random assignment, we asked respondents about their views on the US Constitution using the seven questions that make up Brown and Pope’s measure of respect for the Constitution (Brown and Pope Reference Brown and Pope2019, 1146–49). The complete question wording is included in the Appendix. We note that “constitutional veneration” as we understand it – a diffuse, implicit attitude, or feeling toward the Constitution – does not readily lend itself to direct measurement. As Brown and Pope (Reference Brown and Pope2019, 1146–48) suggest, however, a more indirect approach that asks respondents several questions gauging their attitudes about the Constitution across different dimensions should help triangulate for each respondent this more fundamental, background attitude, or feeling toward the Constitution. For our purposes, then, the questions that constitute Brown and Pope’s measure collectively should reveal an underlying posture toward the Constitution that at least strongly correlates with an individual’s propensity to revere the Constitution. Footnote 12 As such, it is a useful proxy for veneration and a better one than the single-question measure used in Experiment 1. After responding to the constitutional respect battery and completing the MVC exercise, respondents were randomly assigned to treatment and control conditions that are identical to those used in the CCES experiment.

Experiment 2 results

The middle panel of Table 1 presents the average treatment effects for the two issue proposals. Consistent with the results based on both the original Zink and Dawes study and the CCES replication study, the treatment increased support for the status quo in the Lucid study. The treatment effect sizes are also in line with both studies.

Figure 3 plots the treatment effect among those classified as having a high level of respect for the Constitution versus among those with lower levels of respect. Footnote 13 This allows us to evaluate our expectation that the veneration treatment will increase support for the constitutional status quo (i.e., increase opposition to the amendment proposals) among those expressing greater respect for the Constitution, the group most likely to contain venerators. The treatment increased opposition to the collective bargaining and 2/3 majority proposals by 27 and 21 percentage points, respectively. Our treatment had little or no effect among those with lower levels of respect for the Constitution.

Figure 3 Treatment effects and 95% confidence intervals (associated with two-tailed t-tests) for the collective bargaining and 2/3 majority conditions among high and low respect respondents. Average support for the constitutional status quo among each group is presented in Appendix Table 7.

Discussion

Our results indicate that, among those possessed of it, constitutional veneration translates into a higher baseline level of resistance to constitutional amendment. Our findings bolster Zink and Dawes’s conclusion that a specific bias in favor of the Constitution can act as an obstacle to constitutional amendment and demonstrate that their findings generalize to a representative sample.

We have focused narrowly on testing whether something like constitutional veneration biases individuals against amending the Constitution, but this study suggests other important questions. Perhaps the most important first step for future research is to better specify and measure constitutional veneration. It also is important to identify the determinants of constitutional veneration. Is one’s tendency to revere the Constitution a product of socialization, for example, or does it results from specific knowledge of the Constitution? Our own brief analysis, presented in the “Political and Constitutional Knowledge” section of the Appendix, finds that our treatment effects do not differ based on political or constitutional knowledge, which indicates that more knowledgeable respondents are not significantly more likely to revere the Constitution. This offers some evidence that veneration is more of a “prejudice” (to use James Madison’s term) rather than a rational evaluation based on knowledge of the Constitution’s content and history. But this question warrants more sustained analysis.

The question of whether the formal rules governing the amendment process might shape constitutional attitudes also remains very much alive. Ginsburg and Melton (Reference Ginsburg and Melton2015) find that the relative difficulty of a country’s formal constitutional amendment procedures is a poor predictor of how frequently it is amended, and they argue instead that a country’s “amendment culture” better explains its constitutional amendment rate. Footnote 14 Consistent with this view, our results suggest that, at least in the USA, there is an aspect of institutional inertia that is attributable in part to the public’s attitudes about the sanctity of founding documents. But because our studies relate only to a single institutional context (the US federal Constitution), we do not address the possibility that veneration or “amendment culture” itself is influenced by the amendment rules. Zink and Dawes’s original study, which also included experiments involving the US state-level context, find that respondents’ bias in favor of the constitutional status quo is weaker at the state level, where it is much easier to change the constitution and thus constitutional change is more frequent. Brown and Pope (Reference Brown and Pope2019) similarly find that individuals in the USA have much different attitudes about their state constitutions that make them more accepting of constitutional change at the state level compared to the federal level. These studies thus offer some evidence that the institutional context may shape how individuals feel about a constitution and their willingness to support changes to it, but the question deserves more attention.

Finally, these findings also have important normative and practical implications. They indicate that, rather than taking part in a truly sovereign people that actively (re)considers the Constitution’s adequacy for contemporary circumstances, reverence for the Constitution may lead many individuals to reflexively support the constitutional status quo. Constitutional veneration thus can contribute to constitutional stasis – not necessarily a bad thing – or, more problematically, facilitate informal constitutional change by means other than those prescribed by the Article V, effectively leaving it to political elites to “amend” the Constitution through interpretation, executive order, or legislation. That is, as Zink and Dawes suggest, individuals’ reverence for the Constitution can subtly encourage them “to cede their authority to change the Constitution to the very government officials the Constitution is meant to constrain” (Zink and Dawes Reference Zink and Dawes2016, 556).

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2021.29

Data Availability Statement

The data, code, and any additional materials required to replicate all analyses in this article are available at the Journal of Experimental Political Science Dataverse within the Harvard Dataverse Network, at: doi:10.7910/DVN/VZE18R.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to report.