Introduction

Because men and women are socialized differently towards the topic of politics, they grow an interest and come to learn about different things; however, the most used and readily available methodology dedicated to measuring political knowledge and interest is unable to grasp the implications that gender socialization processes have on what women and men learn or find interesting about politics. This happens because political surveys usually look for knowledge about – or an expression of interest in – institutions and national politics, which are male-dominated fringes of society, where women are nowhere close to parity. Unsurprisingly, data systematically show men as more knowledgeable and interested in politics than women, and women more apt to say that they ‘don't know’ even when they do know the answer. Ultimately, this bias extends from social researchers to public opinion, and from the data collection process to results, producing superficial and distorted interpretations about gender-based political behaviour.

Most attempts at making a fairer, gender-balanced measurement of political knowledge have asked respondents questions that make a clear reference to women involved in political institutions and have assumed these to be ‘female-relevant’ (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Quintelier and Reeskens2007; Dolan, Reference Dolan2011). Others have tried to encourage women not to say ‘I don't know’ before questions of political knowledge, as by concealing their knowledge they appear in data as less knowledgeable than they really are (Mondak and Anderson, Reference Mondak and Anderson2004; Ferrín et al., Reference Ferrín, Fraile and García-Albacete2017; Miller, Reference Miller2019). These adjustments alone are not sufficient; there are, in fact, areas of politics and political issues – for instance, healthcare and welfare policies – that women know more of as compared to men, for which they express as much knowledge as men, and that they find more interesting (Campbell and Winters, Reference Campbell and Winters2008). However, these issues, despite being truly relevant to women, are very rarely included in large-scale investigations and have mostly occurred in small studies dedicated to the observation of gender differences.

The lack of responsiveness to the calls for gender-sensitive renewal in this area of research and methodology needs to be readdressed. In fact, while other areas of investigation, such as political activism, have pushed to include a more sensitive mix of indicators in political surveys (see Inglehart and Norris, Reference Inglehart and Norris2000; Stolle et al., Reference Stolle, Hooghe and Micheletti2005), questions about knowledge and interest lack of gender-sensitive implementation and systematization.

I argue that women and men's knowledge and interest is more virtuously measured when people are prompted to disassociate the idea of political knowledge and interest to that of knowing and taking an interest in institutional and national politics exclusively. Specifically, I concentrate on three gender gaps – the knowledge, the interest, and the knowledge expression gap – and show how they strongly depend on how the researcher chooses to design question content and format. I therefore provide an encompassing account of all three gender gaps which have, instead, often gone under scrutiny singularly, as independent antecedents of political engagement.

To this end, I administer two survey experiments on a sample of about 200 Italian university students, who were asked to voluntarily fill an online questionnaire. So as to measure gender patterns of political knowledge, I offer an original set of questions, the content of which varies across three dimensions of knowledge: the topical, the temporal, and the female-relevant. So as to control for gender patterns of expression of knowledge, I randomly discourage individuals from replying ‘I don't know’ to these questions. So as to measure gendered patterns of interest in politics, I prompt a random half of the students to disassociate the idea of political interest to that of taking an interest in institutional and national politics exclusively, before asking them to self-rate their level of interest. The results of this research provide enough evidence to show that (a) men are made to look disproportionately more knowledgeable and interested by the methodology traditionally employed in large-scale surveys of political behaviour; and that (b) having respondents think about politics in a more articulated way proves to be an effective measure of women and men's levels of political knowledge and interest.

The gender gaps in political knowledge, knowledge expression, and interest

The gender gaps in political knowledge and expression of knowledge

Women have come a long way from the universal suffrage and have become critical actors of the public scene; nevertheless, data still report the systematic presence of a gender gap in political knowledge in large portions of the world (Frazer and Macdonald, Reference Frazer and Macdonald2003; Fraile, Reference Fraile2014; Fortin-Rittberger, Reference Fortin-Rittberger2016). The fact that certain social targets cannot dispose of the same intellectual means as other fellow citizens is problematic in the context of a representative democracy, for which citizens' involvement in the decision-making process is empowering. Informed citizens can hold their representatives accountable for the quality of their service with voting (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1980; Berelson et al., Reference Berelson, Lazarsfeld and McPhee1986), while less knowledgeable citizens might find it hard to have their rights represented. In this light, knowledge gaps between women and men represent a strong sign of social and political inequality.

Literature has often reasoned on why women are neither as informed nor eager to speak out before a question about political content. It has pointed to women lacking the resources associated with political engagement – namely the money and time to get informed (Carpini and Keeter, Reference Carpini and Keeter1993; Verba et al., Reference Verba, Burns and Schlozman1997). For instance, women tend to allocate more personal time to taking care of their family, provided they have one, than to newspaper reading so that they are less likely to be accustomed to what is happening daily at the national political level (Ross and Carter, Reference Ross and Carter2011; Aalberg et al., Reference Aalberg, Blekesaune and Elvestad2013; Curran et al., Reference Curran, Coen, Soroka, Aalberg, Hayashi, Hichy, Iyengar, Jones, Mazzoleni, Papathanassopoulos and Rhee2014). Literature has also focused on the processes of socialization that articulate around gender, and that assign men and women to different roles within society; according to these directives and with some simplification, men are encouraged to chase status and independence, while women are traditionally and normatively dispensed from engaging with political institutions and discouraged to do so from a very young age (Bos et al., Reference Bos, Greenlee, Holman, Oxley and Lay2022). This creates a negative feedback loop that leads to gender gaps in the quantity and quality of political engagement (Ferrín et al., Reference Ferrín, Fraile and Rubal2015; Quaranta and Dotti Sani, Reference Quaranta and Dotti Sani2018). In fact, women develop weaker political ambition as compared to men, and are less likely to run for office or learn how to do so (Fox and Lawless, Reference Fox and Lawless2010; Preece and Stoddard, Reference Preece and Stoddard2015; Schneider and Bos, Reference Schneider and Bos2019). When they do run for office, they are often subject to either stereotypes regarding their inability to successfully fulfil leadership expectations, or judgements about them not complying with their gender role traits (Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Holman, Diekman and McAndrew2016; Schneider and Bos, Reference Schneider and Bos2019). Underrepresentation and lack of role models in political institutions, especially at the vertices, further discourage women to take an interest, whereas the male domination of institutions encourages men to participate even more (Verba et al., Reference Verba, Burns and Schlozman1997; Wolbrecht and Campbell, Reference Wolbrecht and Campbell2005).

Recent literature has argued that the gender gap in political knowledge we often see in data needs further investigation in relation to these processes of socialization. The claim is that women and men come to learn and know about different political things, and that the gender gap is due to a poor selection of knowledge questions on behalf of surveyors, who often prioritize what men deem important about politics. In fact, in large-scale surveys, political knowledge is traditionally computed through items that test the citizen's familiarity with political leaders, parties, and alignments, and with the constitutional principles of the democratic institutions – the so-called ‘rules of the game’. In fact, questions may ask for the majority rule and the separation of power; for the identification of national and international political figures and their role in a party, cabinet, or other institution; for the length of an institutional figure's term, or whose responsibility it is to determine if a law is constitutional (see Caripini and Keeter, Reference Carpini and Keeter1993; Miller, Reference Miller2019; Pereira, Reference Pereira2019). These are all topics pertaining to political institutions that men deem more important and have higher chances of learning than women, depending on a mix of structural and socialization factors, as previously established. Hence, limiting the measurement of ‘general’ political knowledge to knowledge about institutions disregards the implications of gender-based socialization processes on women and men's political learning outcomes, and automatically awards the comparative advantage of answering correctly to men.

Most attempts at balancing knowledge questions to custom the measurement of political knowledge in a gender-sensitive manner have contributed only marginally, often by conserving the traditional focus on institutions but adding a clear reference to women involved in high political positions. In other words, respondents have been invited to guess the proportion of seats held by women in national institutions, as well as the name of women in high-level political roles. These have been referred to as ‘female-relevant’ questions. However, while this strategy has shown, on the one hand, to significantly reduce or wipe out men's advantage in knowledge questions (see Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Quintelier and Reeskens2007; Dolan, Reference Dolan2011), on other occasions, it has borne mixed results, as women still have a harder time identifying political figures as compared to men, be them male or female politicians (see Stolle and Gidengil Reference Stolle and Gidengil2010; Ferrín et al., Reference Ferrín, Fraile and García-Albacete2018). Introducing questions in the measurement of political knowledge that can appeal to women directly is, on the one hand, a good attempt for drawing women's attention on a topic they pay less attention to in life and would pay less attention to in related knowledge tests. After all, men tend to do the same: while they may be more able to recognize political leaders in general, they are much more likely to recognize men, which suggests that they also pay less attention to their counterparts in politics (Dolan, Reference Dolan2011). On the other hand, a specific reference to women in political institutions might not be sufficient to turn the measurement of political knowledge into a gender-sensitive one: there seems to be a deeper topical segregation of knowledge between women and men that must be addressed.

Interestingly, when survey questions have considered other topical dimensions of political knowledge, such as ‘policy-specific’ issues, women appear as knowledgeable as men (as in Barabas et al., Reference Barabas, Jerit, Pollock and Rainey2014). Specifically, this set of issues refers to the offer of governmental services and benefits – for example, work or welfare-related policies, tax cuts or allowances, and so on – and it is crucially related to citizens' daily-lives requirements and needs. For this reason, it represents political information that active citizens should be aware of. Crucially, women, who are often burdened with family care duties, such as childbearing or taking care of the elderly, may spend more time learning about how to benefit from certain governmental services dedicated to these issues as opposed to men, or as opposed to spending time acquiring other types of political information (Stolle and Gidengil, Reference Stolle and Gidengil2010). Additionally, the more the policy-specific issue under investigation complies with the duties that come with women's social gender role, the more women know about it as compared to men. Indeed, in other research, women have outperformed men on political questions regarding health and childcare – that is, the cost of screening tests, where to report of a child being abused (Stolle and Gidengil, Reference Stolle and Gidengil2010), and where to go to obtain a health card (Ferrín et al., Reference Ferrín, Fraile and García-Albacete2017). Implementing policy issues, especially if female-relevant, in the mix of questions does consider the different socialization paths to politics of women and men; it thus seems to be a more effective strategy to renew the measurement of political knowledge in a gender-sensitive direction.

The choice of measuring political knowledge as a one-dimensional concept, which characterizes traditional indexes made on the blueprint of the one used by Carpini and Keeter in their seminal research (Reference Carpini and Keeter1993; Reference Carpini and Keeter1996), has often been criticized by many scholars in reference to its gender-related consequences. In fact, apart from being differently susceptible to the topic under investigation, women's knowledge may vary across the temporal dimension of political content – that is, according to whether the focus of question content concerns a historical or a currently salient piece of political news. Generally, questions of political knowledge ask for current political facts, which women have shown to be less knowledgeable about as compared to men (Barabas et al., Reference Barabas, Jerit, Pollock and Rainey2014; Ferrín et al., Reference Ferrín, Fraile and García-Albacete2018), while not much of a gender gap in political knowledge is found when questions ask for historical political information (Barabas et al., Reference Barabas, Jerit, Pollock and Rainey2014; Ferrín et al., Reference Ferrín, Fraile and García-Albacete2018). This has been reasoned by previous literature on the basis of women being less exposed to breaking news, and less targeted as the recipients of news in the mass information environment (Ross and Carter, Reference Ross and Carter2011; Aalberg et al., Reference Aalberg, Blekesaune and Elvestad2013; Curran et al., Reference Curran, Coen, Soroka, Aalberg, Hayashi, Hichy, Iyengar, Jones, Mazzoleni, Papathanassopoulos and Rhee2014). On the contrary, the knowledge gender gap is smaller as regards information that has been circulating for longer, in that women have had more time to catch up. Moreover, just as in the case of policy-specific issues, if questions about historical facts are also female-relevant, this might have women responding just as well as men; however, the effects on the gender gap in political knowledge of this combination of question content features is largely understudied.

A second strand of literature committed to studying the gender gap in political knowledge argues that there seems to be a sort of ‘gendered psyche’ (Fox and Lawless, Reference Fox and Lawless2010) – that is, an inherent feeling of inadequacy and low self-efficacy on behalf of women and a sense of self-assurance on behalf of men – before questions of political knowledge, which translates into a tendency of women not to provide a valid answer to questions they know the answer to, but resort to DKs more often instead and more often than men (Rae Atkeson and Rapoport, Reference Rae Atkeson and Rapoport2003; Mondak and Anderson, Reference Mondak and Anderson2004; Miller and Orr, Reference Miller and Orr2008; Preece, Reference Preece2016; Ferrín et al., Reference Ferrín, Fraile and García-Albacete2017; Ferrín et al., Reference Ferrín, García-Albacete and Sánchez-Vítores2022). I refer to this diverging gendered tendency as the gender gap in the expression of knowledge. The genesis of this gap can also be traced down to processes of gender socialization towards politics, but it focuses more on how these affect women and men's performances in knowledge quizzes rather than on how they lead to differential knowledge between women and men. In detail, there seems to be the presence of a stereotype threat before questions about political knowledge that affects women's performance negatively (Ihme and Tausendpfund, Reference Ihme and Tausendpfund2018). In other words, the abundance of negative stereotypes regarding women's ability to perform as well as men in both political institutions and political-related tests is said to affect women by lowering their self-reported motivation, their confidence and memory capacity, requiring stronger cognitive effort to answer. Men, on the other hand, usually tend to overstate their capabilities in political-related tasks and quizzes (Fortin-Rittberger, Reference Fortin-Rittberger2016; Pereira, Reference Pereira2019), as a consequence of being, on the contrary, positively stereotyped as more knowledgeable. This can inflate the gender gap in political knowledge by making women appear even less informed about politics and men even more.

Research attempting to minimize the gender gap in expression of knowledge, and hence soften the tendency of women to resort to DKs, has succeeded by using certain survey design choices, such as employing a DK-discouraging protocol, where DK answers are eliminated or strongly unadvised. In fact, discouraging DKs can eliminate about half or more of the gender gap in political knowledge, as women uncover some hidden knowledge (Mondak and Anderson, Reference Mondak and Anderson2004; Lizotte and Sidman, Reference Lizotte and Sidman2009; Miller, Reference Miller2019). However, this strategy boosts guessing among men (Mondak and Anderson, Reference Mondak and Anderson2004; Fraile and García-Albacete, 2017), and the effects of guessing depend on the mix of open- vs. closed-ended knowledge items. Literature thus appears unresolved as regards the ‘best practices’ that can be used to minimize the impact of women and men's patterns of knowledge expression on the gender gap in political knowledge, and has produced very mixed results (see Luskin and Bullock, Reference Luskin and Bullock2011; Ferrín et al., Reference Ferrín, Fraile and García-Albacete2018).

Both the socialization theory and the stereotype threat theories face, however, a big constraint as regards their empirical verification. For one, political knowledge indexes that are predominantly in use are built on the blueprint of Carpini and Keeter's five-item scale (Reference Carpini and Keeter1993, Reference Carpini and Keeter1996), hence offer knowledge about institutions as the only proxy for the measurement of political knowledge. Consequently, there is a substantial lack of representative data showing what women and men know about other domains of politics. Similarly, the scholarship investigating the gender gap in knowledge expression has mainly been able to observe gendered patterns of behaviour when question content is traditional, in that it concerns issues of institutional and national politics. It is then very rare to find research observing women and men's propensity to express their knowledge before questions that deal with other types of political content. Yet, gender differences in knowledge expression may also be related to the limited and biased choice of question content in standardized surveys, which is also responsible for distorting the measurements of the gender gap in political knowledge. In other words, it may be that the stereotype threat is circumscribed to the same cluster of questions that is also subject to criticism for failing to measure other types of political expertise. The limited literature that has tackled this issue – although only secondarily – has in fact shown that women tendentially answer less to questions that are related to topics of institutional politics even when they do not challenge knowledge but ask for opinion instead (Rae Akenson and Rapoport, Reference Rae Atkeson and Rapoport2003), but that when asked about policy-specific issues, they bear about the same chances as men of providing a valid or a correct answer (Fraile, Reference Fraile2014), regardless of whether the DK option is encouraged or discouraged (Miller, Reference Miller2019). Changing the content of the questions about political knowledge can then both help researchers to measure knowledge in a more gender-sensitive manner and minimize the gender gap in the expression of knowledge.

To test this theory, I administer respondents a series of eight political knowledge questions, the content of which varies along the three dimensions of political knowledge – the topical (institutional politics vs. public policies), the temporal (current vs. past political affairs), and the female-relevant (no reference vs. clear reference to women in politics). In accordance with the literature presented, I expect women and men's levels of knowledge to vary accordingly. Specifically, I expect the knowledge gap to be in favour of men and (a) larger when questions ask for knowledge about either institutional politics or current political issues; and (b) smaller when questions ask for knowledge about either public policies or historical political happenings. Hypothesis H1a reads as follows:

Hypothesis 1 (the gender socialization hypothesis): the gender gap is in favour of men and greater when questions are about institutional politics or current political facts; it is smaller when questions are about public policies or historical political facts.

At the same time, I test the effect that different political content has on women's ability to express knowledge. To do so, for each question of political knowledge, I randomly encourage half of the sample to provide a valid answer via a DK-discouraging treatment, thus compare knowledge gaps among treated individuals to those among respondents in control. If the gender stereotype threat is larger when question content concerns topics of institutional politics or current political facts, as expected, treated women will benefit from treatment and reveal more knowledge than the women in control. I do not expect the same effect on treated men, who would be indifferent to treatment in the same way they are indifferent to the stereotype threat. Relatedly, I suggest the stereotype threat to be smaller in questions about public policies and historical political events; I do not hence expect treated women to reveal with treatment a great deal of otherwise-hidden knowledge on these items. The second hypothesis goes as follows:

Hypothesis 2a (the gender-stereotype hypothesis): treated women reveal more knowledge than women in the control group when questions concern topics of institutional politics or of current political events; they do not reveal more knowledge than the women in control when questions are about public policies or historical political events.

If this were true, the gender gap would decrease between treated men and women on questions regarding institutional or current politics, because of treated women revealing more knowledge. It would not, on the contrary, decrease on questions regarding public policies or historical political events. Following this reasoning, I extend the second hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis 2b: the gender gap in political knowledge decreases with treatment when questions are about institutional politics and current politics; it does not decrease with treatment when questions are about public policies or historical political facts.

The gender gap in political interest

Interest in politics is conventionally measured by having respondents self-assess their level; it is hence difficult to measure objective perceptions. In fact, women are, on average, less interested in politics than men (Kittilson and Schwindt-Bayer, Reference Kittilson and Schwindt-Bayer2012; Fraile and Gómez, Reference Fraile and Gómez2017; Fraile and Sánchez-Vítores, Reference Fraile and Sánchez-Vítores2020), but a non-residual part of the gender gap is due to subjective feelings, and in particular, to the tendency of women to underestate their level of involvement, or that of men to overestimate theirs (Preece and Stoddard, Reference Preece and Stoddard2015; Pate and Fox, Reference Pate and Fox2018). Experimental research has demonstrated that women will declare higher levels of interest in politics once confidence in their own cognitive abilities is boosted (Preece, Reference Preece2016). Yet just like political knowledge, political interest is presented in surveys in very general terms and is hence automatically understood as taking an interest in ‘public affairs’ or ‘national politics’ (Prior, Reference Prior2018; Ferrín et al., Reference Ferrín, Fraile, García-Albacete and Gómez2020).

The effect that this specific understanding of the concept of politics has on the gender gap in political interest is difficult to observe and has indeed been often overlooked in literature. In fact, women are not as interested as men in topics like governmental actors, institutions, and economic affairs (Campbell, Reference Campbell2004; Campbell and Winters, Reference Campbell and Winters2008; Ferrín et al., Reference Ferrín, Fraile, García-Albacete and Gómez2020), but interest rates might change if we allow other issues – for instance, gender issues – to enter the realm of what we define as ‘political’. In fact, when asked to rate their interest in other areas of politics, like local politics and domestic issues, for example, women systematically appear as equally (if not more) interested as men (Coffé, Reference Coffé2013; Sánchez-Vitores, Reference Sánchez-Vítores2019). Women are also reported to be more interested in issues such as education, healthcare, and social policy, all of which are closely related to their personal experience as citizens (Coffé and Bolzendahl, Reference Coffé and Bolzendahl2010).

Gender socialization theories suggest that women are raised differently to men, and that their life experiences reinforce gender-based differences in political behaviour (Jennings, Reference Jennings1983; Verba et al., Reference Verba, Burns and Schlozman1997). As a result, the term ‘political’ might bring different associations for women and men (Fitzgerald, Reference Fitzgerald2013). However, prompting respondents to think about politics in broader terms, maybe including female-oriented political issues as well, has shown to completely close the gender gap in political interest (Tormos and Verge, Reference Tormos and Verge2022). Similarly, by randomly stimulating respondents to disassociate the general term ‘interest in politics’ to its common understanding of ‘interest in institutional politics’, and thus think about politics as including the so-called gender issues as well, I wish to explore the degree to which this narrow conceptualization of politics is inflating the gender gap in political interest. I expect the gender gap in favour of men in political interest to narrow as issues that are regarded as relevant to women are included in the definition of what is political. The last hypothesis can be articulated as follows:

Hypothesis 3 (the interest gap hypothesis): the gender gap in political interest is (a) greater, when the concept of political interest is given a generic definition; and (b) narrower, when respondents are prompted to think about political issues in broader terms.

Data and methods

Data were collected first-hand on about 200 bachelor students from the Departments of Social and Political Sciences and that of International, Legal, Historical and Political Studies via an online questionnaire. Students were invited to voluntarily complete a 5-minute online survey; most students did so in a lab, others were given the link and asked to kindly find time to fill it at home. The questionnaire included eight questions of political knowledge, a question asking respondents to self-rate their level of political interest, and a battery of 14 political statements asking respondents for their level of agreement to each. A large part of the data collection process was carried out between June and November 2019, and briefly reiterated in June 2020. The first part of the study is dedicated to measuring how levels of political knowledge change according to the combination of question content and DK protocol. Instead, the second part of this study focuses on self-reported levels of political interest.

Experiment #1: political knowledge and expression of knowledge

The first part of this study wishes to observe gendered patterns of knowledge when various question content is combined to a DK-discouraging protocol. To this end, I designed a battery of eight knowledge items on the blueprint of the Barabas et al.'s’ (Reference Barabas, Jerit, Pollock and Rainey2014) model, accounting for both the topical and temporal dimensions of political knowledge. I hence offer respondents (a) two questions regarding two historical political events – one of which is of institutional nature, while the other is about an important public policy reform; (b) two questions regarding more modern public policies; and (c) four questions about institutional politics, further detailed in two questions asking for knowledge about political leaders and two questions asking for knowledge about percentages of MP representatives. Questions about institutional politics are based on the XVIII Italian legislation. So as to integrate the third dimension, that of gender relevancy, for each topical and temporal characteristic of knowledge, I prepared a female-relevant question as detailed in Table 1. Items are ‘female-relevant’ since they ask for political information that is rated as important to women, in accordance with the literature presented in the theoretical framework of this paper. Therefore, as for the topics of institutional politics, the female-relevant questions ask to identify a woman in a leading political position and the percentage of female MPs; as for the policy-specific issue, I ask for the length of compulsory maternity leave in Italy; as for the historical fact, I ask respondents to place in history when divorce became legal, as it marks a pivotal point in time in the development of women's rights in Italy. The other half of the items do not reference women specifically in any way, and neither evoke the duties and expectations connected to women's social gender role.

Table 1. Open- and closed-ended questions of political knowledge administered to respondents and their correct answer

Questions were presented in random order.

Item format varies from open- to closed-ended depending on the complexity of the question, in that the hardest knowledge questions offer a response set of four possible options. The text and nature (open- vs. closed-ended) of each question is detailed in Table 1. Respondents were asked to answer two blocks of questions, one including the four closed-ended questions, the other grouping all four open-ended. The order of the blocks varied randomly, so that each respondent could have either answered the closed-ended questions first and the open-ended set thereafter, or vice versa. The questions included in each block were also presented to respondents in random order. For each block of questions, respondents were randomly assigned to a DK-discouraging treatment. In the four closed-ended items, treated individuals, as opposed to those in control, were not provided the DK option in their response set, although they were not obliged to answer, and questions could be left vacant. Instead, in the four open-ended questions, individuals in the treatment group were prompted to provide a solid answer by receiving an introduction discouraging them to say ‘I don't know’; respondents in the control group instead received neutral instructions on how to fill in the blanks.

I measure gender gaps by calculating the percentage-point difference of women and men answering correctly across each knowledge item and experimental group. I use two-sample t-tests to verify whether any difference in magnitude of the gender gaps is statistically significant.

Experiment #2: political interest

In this second experiment, all respondents were asked to self-declare their level of interest by stating whether they were very interested, fairly interested, or not at all interested in politics. A random half of respondents (the control group) was asked to do so straight after answering the questions about political knowledge. The other half (the treated group) were first invited to express their level of agreement or disagreement with a few provocative statements about politics. Individuals were presented with 14 political issues on various topics – taxes, pro-life or pro-choice policy matters, vaccines – all of which are detailed in Table 2. Half of these items – that is, seven – focus on female-relevant aspect of each topic – for example, abortion, the tampon tax, and sexual assault, whereas the other seven are unrelated to gender, or make no clear reference to women or to women's rights – for example, euthanasia, immigration, workers' conditions, and so on. All statements were presented in random order to respondents.

Table 2. List of statements presented to respondents as a measurement of political opinion

Statements were presented in random order.

Results

Knowledge gaps when knowledge is expressed

I present here Tables 3 and 4, which show the percentages of men and women answering correctly in the control and treatment group to, respectively, the two questions about political leaders, the two questions about policy-specific issues (Table 3), the two questions asking for information about the current representation in Parliament, and the two questions asking about historical political events (Table 4). Knowledge gaps are presented in percentage-point differences (p.p.) for both the control and treatment groups; the difference in p.p. of the gaps between treatment and control is also displayed. When the difference is positive (last column of Tables 3 and 4), the knowledge gap has enlarged with treatment; when it is negative, the knowledge gap has reduced.

Table 3. Percentages of men (M) and women (W) answering correctly to each question on the topical dimension of knowledge, in control and in treatment respectively

Gender ‘knowledge gaps' (M-W) are displayed for control (M-W)c and treatment (M-W)t; when positive, they are in favour of men, when negative, they are in favour of women. The last column (DIFF) is the difference between gaps in treatment and gaps in control, so it represents whether the magnitude of gender gap has increased or decreased because of treatment. When positive it has increased, when negative, it has decreased.

*P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001.

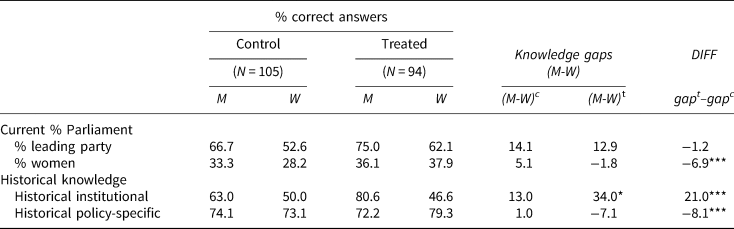

Table 4. Percentages of men (M) and women (W) answering correctly to each question on the temporal dimension of knowledge, in control and in treatment respectively

Gender ‘knowledge gaps' (M-W) are displayed for control (M-W)c and treatment (M-W)t; when positive, they are in favour of men, when negative, they are in favour of women. The last column (DIFF) is the difference between gaps in treatment and gaps in control, so it represents whether the magnitude of gender gap has increased or decreased because of treatment. When positive it has increased, when negative, it has decreased.

*P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001.

We see from the results displayed in Table 3 that allowing question content to vary along the topical dimension – and thus, from institutional politics to policy-specific issues – and combining the different topics to a DK-discouraging protocol has a clear effect on gendered patterns of knowledge. Men have a comparative advantage on women in terms of knowledge for the identification of both political leaders, be them men or women. However, while knowledge gaps are large but not significant in the control groups, men's knowledge advantage grows to a significant extent with treatment – in fact, it almost doubles, increasing of respectively 21.9 and 13.8 percentage points – as men are able to express more knowledge than women. The results suggest that men know more about institutional figures than women on average, especially if male politicians; and that the DK-discouraging treatment seems to be helping them, more than women, express additional knowledge about political leaders. As on the one hand, I had correctly predicted men to know more about political leaders than women, I had not expected them to benefit as much from treatment.

Gender gaps in the two questions about policy-specific items are, instead, very different. In accordance with the gender socialization theory, women know at least as much as men about policy-specific issues, and more than men if the policy-specific issue is also female-relevant. Additionally, treatment uncovers more knowledge on their behalf than on behalf of men on both items. As for the question about maternity leave, the knowledge gap in favour of women additionally grows with treatment of 3 significant percentage points. Instead, as regards the policy-specific question about universal income, appealing to no gender in particular, the gender gap in knowledge is in favour of men in control, although not significantly so, but closes with treatment, and the decrease in magnitude from control to treatment is of 12.7 statistically significant percentage points. Hence, on this occasion, it is women who benefit more from the DK-discouraging treatment in terms of knowledge gains. I can therefore conclude that, as prevented, women know no less and even more than men about policy-specific issues, especially when female-relevant; however, opposite to what hypothesized, they still tend to conceal their knowledge despite the topic of the question is also relevant to them. Indeed, had they not concealed their knowledge, the DK-discouraging treatment would have been ineffective.

The results as shown on Table 4 seem to suggest that the temporal dimension, which refers to the time frame of the issue under investigation – that is, current vs. historical – does not affect political knowledge or expression of knowledge in a systematic gendered manner. In fact, in Table 4, gender gaps are mostly never significant in neither control nor treatment. There is only one exception – the gender gap is in favour of men in correspondence of the historical institutional question, and significant only under the treatment condition. In other words, men know more about the one historical institutional fact but only when encouraged to provide a valid answer. However, being the sole exception, and reflecting exactly the pattern we have witnessed in Table 3, the gender gap for this item is, once more, very likely to be due to the topical domain of the question – that is, institutional politics.

Instead, women can express more knowledge than men with treatment when asked the questions that make a clear reference to women. In fact, they gain more knowledge when asked in treatment about the percentages of women in Parliament, and about the historical policy referring to divorce, and are able to significantly close the gender gaps in political knowledge on both occasions.

The overall combined effect of treatment and content on the gender gap is, therefore, very similar to what we have witnessed in Table 3 – it mostly helps women and men express more knowledge on topics they should have a comparative advantage on their respective counterparts to begin with. I can conclude from results that there is a clear segmentation of political knowledge between women and men, and that this develops alongside the topical dimension first, and the female-relevant second, whereas the temporal dimension of political knowledge does not seem to bear huge gender-related effects. Indeed, men will always have a comparative advantage when questioned about institutional facts and figures, and even more so if treated to a DK-discouraging protocol. Instead, women will have a comparative advantage on men when questioned about policy-specific items and policy-related events and compelled to provide a valid answer, and even more so if the topics of discussion are female-relevant.

The broader the concept, the frailer the interest

The interest gap hypothesis (hypothesis 3) had predicted the gender gap in political interest to narrow when respondents were prompted to think about politics in a broader sense, that is, inclusive of the topics that often go under the label of ‘gender issues’. This hypothesis is confirmed by our results. Table 5 presents the percentage distributions in stated levels of interest of women and men in both the control and treatment groups. The gender gap among those who state they are ‘very interested’ in politics is reported in the last line. It is evident that the gender gap in control – of 43.5 percentage points – is halved to a disparity of 18.5 percentage points with treatment. On the one hand, our last hypothesis is confirmed, as the gender gap shrinks with treatment; however, as opposed to initial predictions, this is not due to women gaining interest, but to men's levels of interest dropping dramatically. In fact, the percentage of men who say they are ‘very interested’ in politics drops from 51.7% in the control group to 26.5% in treatment. Hence, while men are still, on average, more interested in politics than women, when they are prompted to think about politics in different terms than standard, their levels of interest drop significantly. Instead, treatment does not seem to have any effect on women.

Table 5. Percentages of men and women for each category of the political interest scale, both in control and treatment

The magnitude of the gender gap (GG) is reported as the percentage-points difference between the men and the women who state they are ‘very interested’ in politics.

Discussion and conclusions

This paper wished to highlight that committing to the use of traditional survey methodology in the measurement of political knowledge and interest is introducing a bias in favour of men, blowing gender gaps over proportion. I argue that the bias is due to the fact that political knowledge and interest are often understood in both research and public opinion as knowledge and interest in institutional and national politics. I therefore collect sufficient data to show how this distortion becomes obvious – hence, gender gaps are reduced – once respondents are offered knowledge questions about other political areas and issues or primed to place the concept of politics in a larger frame of reference. Both strategies, I suggest, not only control for gender processes of socialization towards politics but can become gender-sensitive and standardized measures of political knowledge and interest.

As for the gender gap in political knowledge, I hypothesized that the gender gap would be in favour of men and large in questions that asked about institutional or current national politics – that is, ‘traditional’ survey question content – but would disappear if other political content was offered instead (in particular, policy-specific issues). I call this the gender socialization hypothesis, on the basis of women being socialized differently, especially towards politics, which results in them prioritizing and learning about different things as compared to men. The results gave credit to this hypothesis by showing that men tendentially know more about political leaders as compared to women, and that women tendentially know as much as men about public policies – and even more than men when public policies are female-relevant. The results hence point to a clear segmentation of political expertise between women and men across the topical dimension of political knowledge – but not only. They also enrich the literature theoretically framing this piece of research and suggesting the gender gap to be conditional to question content (see Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Quintelier and Reeskens2007; Stolle and Gidengil, Reference Stolle and Gidengil2010; Dolan, Reference Dolan2011; Ferrín et al., Reference Ferrín, Fraile and García-Albacete2017) by pinpointing the topic for which women appear to have a larger disadvantage above all – that is, the identification of political leaders. Indeed, less women than men are able to identify political leaders, be them men or women, but women and men perform no differently when questioned on percentages of party and women's representation in Parliament. Political leadership hence seems to be perceived in our sample as the most masculine domain. It does, in fact, promote ideals of power and agency, pursuing status, self-promotion and recognition, all of which are characteristics that are related to the male gender (as seen in Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Holman, Diekman and McAndrew2016). Moreover, men still dominate political positions globally, and in Italy, not only women hold on average only about 30% of the seats in the major law-making institutions, but very few are seen in political leading positions. It is then not surprising to find the rest of the female population as disinterested, disengaged and uninformed about the topic of political leadership. For this reason, I argue that as much as this is important information that citizens should know, and that surveys dedicated to political attitudes should still look for, the identification of female politicians cannot be considered female-relevant in any way and concurrently does not improve the measurement in a gender-sensitive way.

My second hypothesis concerned the ability to express knowledge of women and men. According to this second hypothesis, the presence of a stereotype threat connected to the questions about political leaders and institutions impaired women's performance in knowledge quizzes, to the point they failed to declare what they knew about the topic. I hypothesized that the threat could become smaller either by randomly discouraging DK answers in an experimental design, or by allowing question content to diverge from the traditional questions that intterrogate respondents about their knowledge of institutional politics. The results do not give credit to the stereotype threat hypothesis; in fact, they show that discouraging DK answers influences both women and men's ability to express knowledge in the opposite direction to that predicted. When the DK-discouraging treatment is administered in questions regarding institutional figures, for which men have a conditional advantage on women in terms of knowledge, it helps men more than women express the extra knowledge. This happens despite the one question being, supposedly, female-relevant. Instead, when the DK-discouraging treatment is paired with questions concerning policy-specific topics, women gain more in terms of knowledge after treatment as compared to men, despite the one question not being directly female-relevant. As for the temporal dimension, treatment does not seem to interact with gender in our sample; however, when questions are female-relevant, inasmuch as they reference issues that women would know more about because of socialization factors, it does uncover more knowledge on their behalf, regardless of whether the questions are about historical or current political information. Both women and men then seem to be expressing all of their knowledge on topics they tendentially know less but conceal some knowledge on the topics they know better. Two conclusions can be drawn from this finding: either treatment is not strong enough to overcome the stereotype threat connected to issues of institutional politics, or women are not as knowledgeable about these topics because of socialization factors, and hence do not know the answer or cannot begin to retrieve it from memory even when aided by a DK-discouraging treatment.

Finally, in relation to the gender gap in political interest, the results show that men appear significantly more interested in the topic so long as no framing of the concept of ‘politics’ is provided. Instead, when I force respondents to think about politics as including gender issues as well, men loose interest in a statistically significant manner. Evidence leads to confirm my hypothesis – I had predicted the gender gap in political interest to decrease with treatment – as interest rates decrease for men. This suggests that mostly men might be brought to think about politics in a one-dimensional way, relating it to the topic they are more interested in – that is, institutional politics. Instead, the so-called ‘gender issues’ may not be considered political as unswervingly, which would also explain why they are often seen as a specific niche of political interest or knowledge, as opposed to being considered of ‘general’ knowledge and concern.

Unfortunately, given the limitations related to sampling, and those to the availability of representative data, this paper can only speak of internal validity and not about the whole Italian context. Still, it is interesting to notice how expectations based on gender are already met in young participants, who hence already show to have segmented types of expertise and interests on the basis of gender. As I cannot make further inferences, I encourage future research to replicate these questions upon a representative sample of Italian citizens. In fact, the Italian context makes a very interesting case, as, being a conservative welfare regime (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990; Naldini and Saraceno, Reference Naldini and Saraceno2008), it still puts normative emphasis on the male-breadwinner arrangement of gender roles (Haas, Reference Haas2005; Zagheni et al., Reference Zagheni, Zannella, Movsesyan and Wagner2014) and has a history of poor implementation of work/family–life balance policies, which assigns caring activities to women privately.

My final note goes to research methodologists. Because institutional politics is not considered, as it should, a section of politics that men prefer and know more about than women but is taken as representative of all that politics means, social and political research only considers the latter when collecting data on political attitudes and behaviour. Especially in Italy, there is very little research investigating other dimensions of political knowledge and little data is collected about what women know or are interested in, which made the task of conducting this study quite arduous. The lack of effort is linked to the fact that most research in socio-political behaviour has traditionally been led by men, who we now know to conceptualize the term of ‘politics’ in a very narrow way. Indirectly, this allocates to what men know and are interested in, in a superior position, whereas all else is relegated to a lower status of importance. This research therefore stands as an invitation to provide respondents with a wider definition of what politics is, as to avoid reflecting the researchers' biases upon public opinion.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any public or private funding agency.

Data

The replication dataset is available at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/XQIDHK.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for having given time and attention to this piece, for their help and valuable comments.

Competing Interests

None.