1 Here are a few examples: Bergman v. Minister of Finance and State Comptroller (1969) (I) 23 P.D. 693 (“Judicial Review of Statute” (1969) 4 Is.L.R. 559); Shalit v. Minister of the Interior et al. (1969) 23 (II) P.D. 477, Special Vol. S.J. 35, Akzin, B., “Who is a Jew? A Hard Case” (1970) 5 Is.I.R. 259Google Scholar and Ginossar, S., “Who is a Jew: A Better Law?”, (1970) 5 Is.L.R. 264CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Nationalist Circles (registered association) and 14 Others v. Minister of Police (1970) (II) 24 P.D. 141. (“The Temple Mount Case” (1971) 6 Is.L.R. 257). See also Tamarin v. State of Israel (1972) (I) 26 P.D. 197 containing a further discussion of the concept of Jewish le'om, an ethnic notion not synonymous with nationality.

2 (1950) 4 L.S.I. 114.

3 See precedents quoted supra n. 1, and also Rufeisen v. Minister of Interior (1969) 16 P.D. 2428 where it was held that a Jew who converted could not obtain Israeli nationality under the Law of the Return. (Special Vol. S.J. 1.)

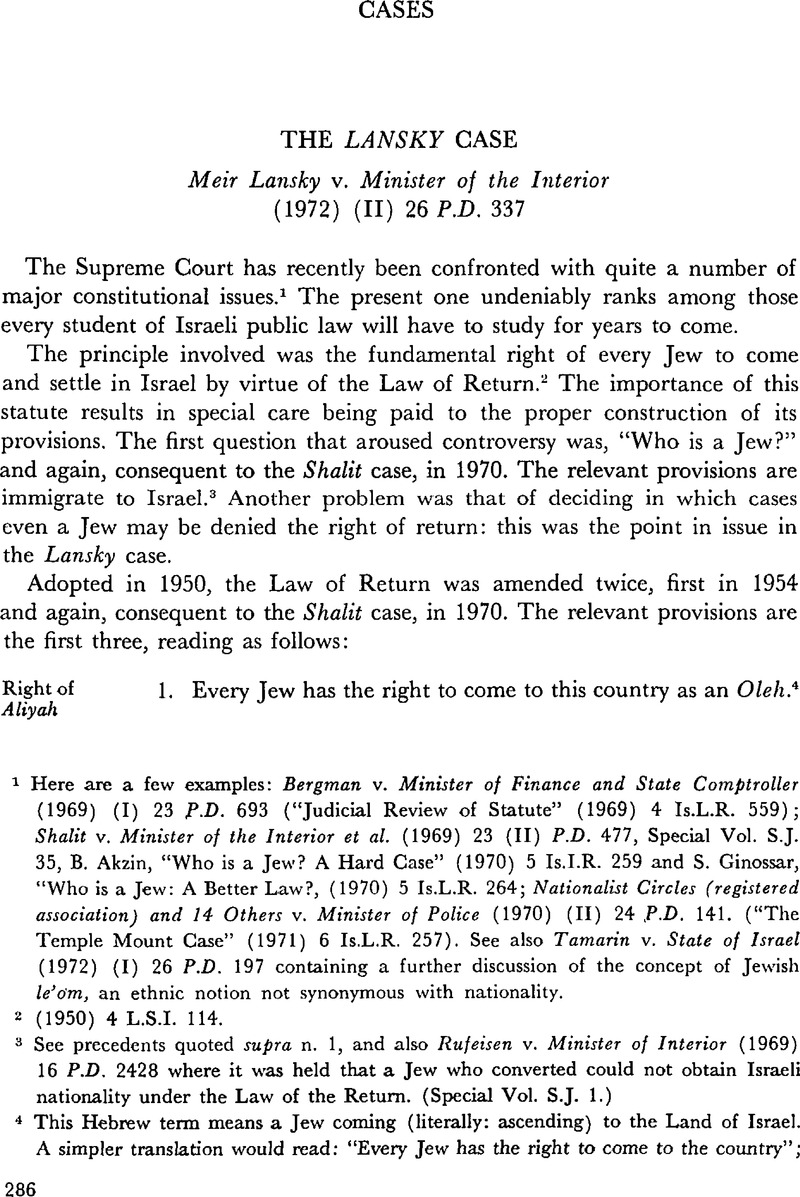

4 This Hebrew term means a Jew coming (literally: ascending) to the Land of Israel. A simpler translation would read: “Every Jew has the right to come to the country”; but it would fail to convey the full significance of returning to settle in the land of the forefathers (aliyah).

5 Joanovici v. Minister of the Interior (1958) 12 P.D. 646. The petitioner who had been living in France for a long time, had been sentenced for collaboration with the Nazis during the occupation. Wanted by the French policy under new charges, he arrived in Israel with a forged passport, but was eventually expelled to France. See also, between the same parties, a subsequent judgment in (1958) 12 P.D. 1959.

6 8 L.S.I. 144.

7 The parliamentary debates are reported in (1953) 15 (1) Divrei Haknesset 816 (first reading) and in (1954) 16 (2) Divrei Haknesset 2459 (second and third readings). Objects and Reasons were published in (1954) Hatza'ot Hok no. 192 at p. 88. At the first reading the Minister of the Interior, Mr. I. Ben Yehuda, mentioned the fact that several foreign governments had expressed readiness to release some Jewish criminals on condition that they proceed to Israel; and before the amendment there was no legal possibility of denying them the benefit of the Law of Return. The Minister also explicity pointed to the future role of the Supreme Court sitting as a High Court of Justice to prevent possible misuse of the new power vested in the Minister. It was probably no coincidence that the Law of Extradition, (1954) 8 L.S.I. 144, was proposed, discussed and adopted parallel to the amendment to the Law of Return; and it will be noted that the statute allows the extradition of Israeli citizens, including those having immigrated by virtue of the Law of Return, provided all other conditions for extradition are met, including that of reciprocity.

8 The most controversial case was that of Soblen, in 1963. Soblen had been convicted in the U.S.A. as a spy. Having been released on bail, he escaped to Israel and availed himself of the Law of Return to be admitted as Oleh. His application was rejected and his petition to the High Court equally failed. He was then expelled to Great Britain; but on board the plane he attempted suicide. He was interned on debarkation and died before deportation to the U.S.A. The Soblen case came up before the English courts and a minor scandal developed. See: R. v. Secretary of State for Home Affairs, ex p. Soblen [1963] 1 Q.B. 329, and the second—more important—case on deportation, R. v. Governor of Brixton Prison, ex p. Soblen [1963] 2 Q.B. 243. In Israel, because of the resentment created by this affair, the Entry Regulations were amended in 1964. Under the new rr. 14–16, implementing the Entry into Israel Law (1952) 6 L.S.I. 159, it is now prescribed that an expulsion order be delivered in writing to the deportee and prohibits its execution for a period of three days after notification: the deportee, although detained, is thus given the opportunity to seek legal advice and to present a petition to the High Court, and mention of this right must be made in the order of expulsion. Such petition will not further suspend the execution of the order, unless the Court otherwise directs. All these rules were strictly observed in the Lansky case.

9 See, for example, Could v. Minister of the Interior (1962) 16 P.D. 1846; Farkas v. Minister of the Interior (1962) 16 P.D. 1547 and 1966; and also the Joanovici and the Soblen cases cited supra nn. 5 and 8.

10 (1962) 16 P.D. 1846.

11 At 1856.

12 Gould had been charged in the U.S.A. with having sold stolen bonds. He had been indicted by a grand jury and a warrant had been issued for his arrest. He managed to escape to Israel with a second passport, obtained under the false pretence of his having lost his original passport. On arrival in Israel he applied for an Oleh's certificate, but without concealing the fact that a prosecution was pending against him in the U.S.A. His application was rejected on the ground of his criminal past; and the Supreme Court did not consider that the Minister had acted ultra vires.

13 Sec. 46 of that Law reads: “Notwithstanding any provision of this Law, the Service Commissioner shall refrain from appointing a person as a State employee if that person committed an offence against this Law in order to obtain the appointment or has a criminal past” (emphasis added) (13 L.S.I. 87).

14 He had been convicted five times, viz., twice for illegal gambling, twice for disorderly conduct (in 1918–20), and one conviction during the Prohibition era. While in Israel a bill of indictment had been issued against him by a Federal grand jury for contempt of court. This enumeration is not particularly impressive. In Gould (supra, n. 9), Sussmann J. remarked that not every conviction is constitutive of a criminal past; parking offences, for instance, are clearly not; and in the present case Agranat P. adds the rather dubious example of pickpocketing.

15 For a good definition thereof, see de Smith, , Judicial Review of Administrative Action (2nd ed., 1968) 271Google Scholar: the authority invested “must act in good faith, must have regard to all relevant considerations and must disregard all irrelevant considerations, must not seek to promote purposes alien to the letter or to the spirit of the legislation that gives it power to act, and must not act arbitrarily or capriciously…”

16 In the original draft the two elements were simply juxtaposed (“the applicant is a person with a criminal past and likely to endanger public welfare”). Before the Supreme Court Lansky's counsel sought to take advantage of this alteration and to plead that, in the present text, not the applicant, but his criminal past should be likely to endanger public welfare; but he later abandoned his interpretation which would lead to sheer absurdity.

17 [1941] 3 All E.R. 338; [1942] A.C. 206.

18 This wide power “would probably not now be applied in other than very special circumstances” (Garner, , Administrative Law (3rd ed., 1970) 152–3Google Scholar; and see Ridge v. Baldwin [1963] 2 All E.R. 66, at 76, where Lord Reid refers to the Liversidge precedent as a “very peculiar decision”; and also Wade, H.W.R., Administrative Law, (2nd ed., 1961) 78.Google Scholar This qualification can apparently be read into the majority opinion of the House of Lords itself. The suggestion that the danger of disclosing secret information may have been the decisive factor was made in a New Zealand case by Turner J. (Reade v. Smith (1959) N.Z.L.R. 996 at 1000, quoted by Garner, op. cit., at 153). See also Allen, C. K., Law and Order (3rd ed., 1965) 256, 370.Google Scholar

19 See [1941] 3 All E.R. 338 at 350: “… In all cases, however, the words indicate an existing something, the having of which can be ascertained and the words do not and cannot mean ‘If A thinks that he has.’ ‘If A has a broken ankle’ does not mean and cannot mean, ‘if A thinks that he has a broken ankle.’ ‘If A has a right of way’ does not mean and cannot mean ‘if A thinks that he has a right of way’. ‘Reasonable cause’ for an action or a belief is just as much a positive fact capable of determination by a third party as is a broken ankle or a legal right.” At 361: “…the words have only one meaning. They are used with that meaning in statements of the common law and in statutes. … After all this long discussion, the question is whether the words ‘if a man has’ can mean ‘if a man thinks he has’. I am of the opinion that they cannot, and that the case should be decided accordingly.”

20 One may wonder why Agranat P. did not on this occasion refer to his own definition of the term “likely” (in Hebrew: 'alul) in the much earlier Kol Ha'am case (1953) 7 P.D. 871 at 887 (1 S.J. 90). The issue concerned the Minister's power to suspend publication of a newspaper if any matter appearing therein is, in his opinion, “likely to endanger public peace”. Reference was made to the Oxford Shorter Dictionary, giving the following definitions: “likely” means probable, such as might well happen, or be or prove true, or turn out to be the thing specified, promising, apparently suitable …; and “probable” means that may be expected to happen or prove true. “Likely” was accordingly construed in the sense of probability and not of bare tendency; and this was in line with the desire to give a liberal interpretation to the (Mandatory) Press Ordinance and promote freedom of expression. But, here again, the same term need not be taken exactly in the same sense in different enactments.

21 “The only question to arise before us is, whether the abundant material available to the respondent was sufficient to show that the petitioner “has a criminal past”. It is beyond discussion that in fact the respondent was honestly “satisfied” that the applicant had such a criminal past and that he was consequently likely to endanger public welfare” (per H. Cohn J. (1962) 16 P.D. 1846, at 1849). This passage was quoted in Lansky (at p. 348) as widening the scope of the Minister's discretion to an extent which, with due respect, may not have been H. Cohn J.'s intention. Cf also Farkas v. Minister of the Interior (1962) 16 P.D. 1547 per Olshan P. at p. 1552.

22 Ridge v. Balwin [1964] A.C. 40.

23 Numerous decision of the U.S. Supreme Court. This is “certainly the oldest established principle in Anglo-American administrative law” (Schwartz, B., An Introduction to American Administrative Law (2nd ed., 1962) 106.Google Scholar Since the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment the principle has been linked with the “due process” clause. See also: Schwartz, B., “Administrative Procedure and Natural Law” in (1953) 28 Notre Dame Lawyer 169Google Scholar; Schwartz, B. and Wade, H.W.R., Legal Control of Government (Oxford, 1972) at 117–8 and 247Google Scholar; and the “Japanese immigrant” case relating to the right of an alien to be heard before deportation (189 U.S. 86 (1903).

24 Conseil d'Etat 5 mai 1944 (Dame Veuve Trompier Gravier), Rec. arr. Conseil d'Etat 133, Dalloz 1945.110, conclusions du commissaire du gouvernement Chenot, note de Soto. In this case the Préfet de la Seine had revoked a permit without giving the beneficiary thereof an opportunity of being heard. This violation of what came to be included in the “principes généraux du droit” was held to vitiate the decision taken by the préfet.

25 Zeev Altegar v. Mayor of Ramat Gan (1966) (I) 20 P.D. 29; Petah-Tiqvah v. Tahan (1969) (II) 23 P.D. 398.

26 The judgment quotes Jaffe, , Judicial Control of Administrative Action (Boston, 1965) 596 and 622–3.Google Scholar

27 Besides the Audi alter partem rule, mention should be made of bias in all its forms. Israeli precedents where these principles were referred to are cited in the judgment at p. 355 et seq.

28 The authorities cited in support include: Reg v. Deputy Industrial Injuries Commissioner (1965) 1 Q.B. 456 (per Pollock J. at 488); In re K. (Infants) [1965] A.C. 201: “No one would suggest that it is contrary to natural justice to act upon hearsay” (per Lord Devlin); T.A. Miller v. Minister of Housing [1968] 2 All E.R. 633, at 634 (per Lord Denning).

29 The privilege against self-incrimination is not linked with the principles of natural justice. The Supreme Court therefore holds that the Minister was reasonably authorized to infer that Lansky's refusal to reply indicated that he was involved in illegal gambling.

30 It should be noted that it had already been ruled in a former case that this possible consequence of expulsion is legally irrelevant (second Joanovici case (1965) 19 P.D. 1959 at 1960). See also Gouldman, M. D., “The Right to Return and the Problem of the Fugitive Offender” in Israeli Reports to the Seventh International Congress of Comparative Law (Jerusalem, 1966) 92.Google Scholar