No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 July 2014

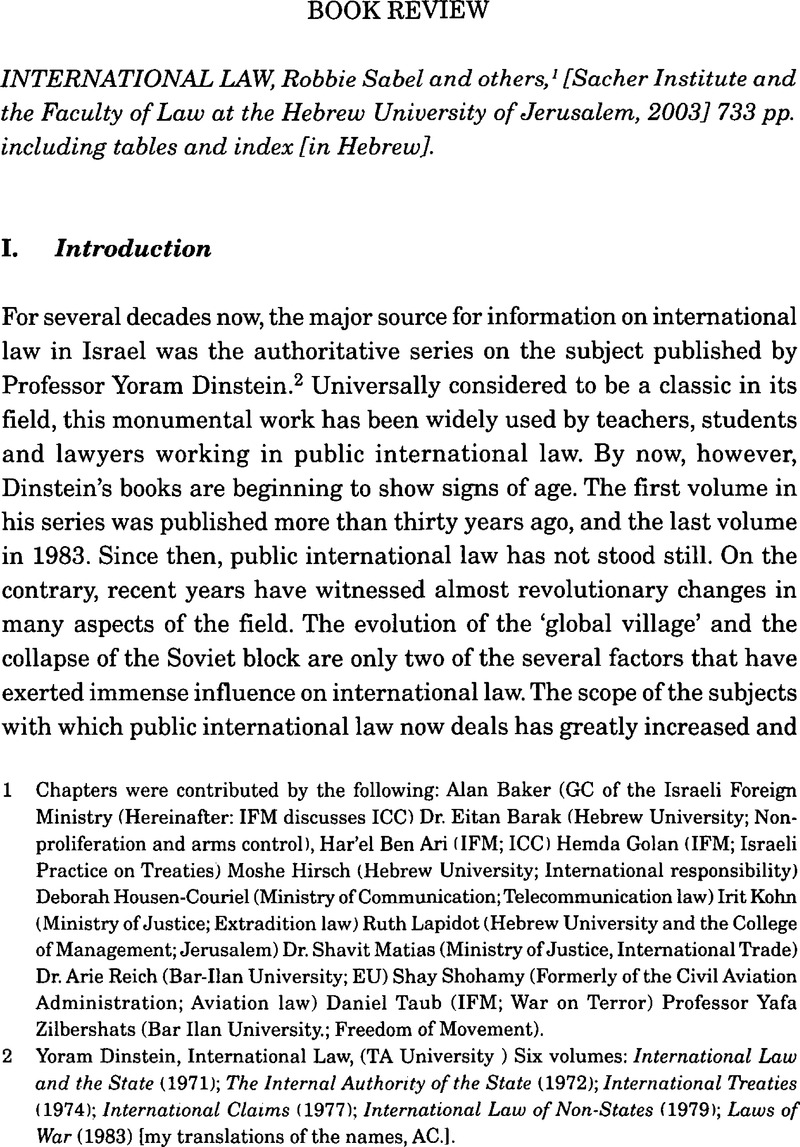

1 Chapters were contributed by the following: Alan Baker (GC of the Israeli Foreign Ministry (Hereinafter: IFM discusses ICC) Dr. Eitan Barak (Hebrew University; Non-proliferation and arms control), Har'el Ben Ari (IFM; ICC) Hemda Golan (IFM; Israeli Practice on Treaties) Moshe Hirsch (Hebrew University; International responsibility) Deborah Housen-Couriel (Ministry of Communication; Telecommunication law) Irit Kohn (Ministry of Justice; Extradition law) Ruth Lapidot (Hebrew University and the College of Management; Jerusalem) Dr. Shavit Matias (Ministry of Justice, International Trade) Dr. Arie Reich (Bar-Ilan University; EU) Shay Shohamy (Formerly of the Civil Aviation Administration; Aviation law) Daniel Taub (IFM; War on Terror) Professor Yafa Zilbershats (Bar Ilan University.; Freedom of Movement).

2 Yoram Dinstein, International Law, (TA University) Six volumes: International Law and the State (1971); The Internal Authority of the State (1972); International Treaties (1974); International Claims (1977); International Law of Non-States (1979); Laws of War (1983) [my translations of the names, AC.].

3 E.g. the authority of the international criminal court for former Yugoslavia over crimes in Bosnia is based on the actual responsibility of Serbia to the Serb-Bosnia Militia.The Prosecutor vs. Tadic, Decision of the Appeals Chamber of the International Criminal Court for the Former Yugoslavia (15.7.1999)

4 Franck, Thomas M., The Power of Legitimacy Among Nations (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1990)Google Scholar

5 The New Haven School of International Law is mentioned in just one paragraph and receives no further elaboration. Neither the feminist nor economic approaches to international law receive any notice whatsoever. International relations scholarship is likewise avoided.

6 For example in the very short discussion of universal jurisdiction at 61.

7 Chapter 8.

8 See e.g. Spiro, Peter J., “New Global Potentates: Nongovernmental Organizations and the ‘Unregulated’ Marketplace” (1996) 18 Card. L. Rev. 957Google Scholar.

9 In the Israeli context, the title of this book might not be altogether precise. Israeli law schools distinguish between public international law, which is the subject of the volume under review, and private international law, which is concerned with what American law schools sometime refer to as the “conflict of laws”. To the Israeli reader, the term ‘international law’ connotes both subjects.

10 Chapter 24, at 497–536.

11 Chapter 29, at. 631–640.

12 Thus p. 516 informs us that the provisions of the Warsaw Treaty of 1929 set the ceiling of liability for lost luggage at $16 for every kilo. Israel has incorporated the first and second Montreal protocol of 1975 and therefore the ceiling of liability has been raised to $20 for every kilo.

13 Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer, (1987) 26 I.L.M. 1516Google Scholar.

14 The Montreal Protocol is mentioned in only one footnote (n. 35, at 636).

15 President Barak has recently suggested that the most important of all Human Rights is the right for human dignity, and the next in the order of importance is the right of equality. Barak, Aharon, “A Judge on Judging: The Role of a Supreme Court in a Democracy,” (2002) 116 Harv. L. Rev. 16, at 44–46Google Scholar.

16 See generally: Lowenfeld, Andres, International Economic Law (2002)Google Scholar.

17 E.g. Ratner, Steven R., “Corporations and Human Rights: A Theory of Legal Responsibility” (2001) 111 yale L. J. 443CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

18 This is of course a question that lies at the foundation of “the war against terrorism” declared by the US. Most legal scholarship in the US on this subject has focused on the legality of the use of force in Afghanistan and the legality of the incarceration without trial in the Guantanamo base of people captured in Afghanistan. E.g., Franck, Thomas M., “Terrorism and the Right of Self Defense” (2001) 95 Am. J. Int'l L. 839CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Cassese, Antonio, “Terrorism is also Disturbing some Crucial Legal Categories of International Law” (2001) 12 Eur. J. Int'l L. 993CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

19 Chapter 22.

20 Chapter 20, at 447–449.

21 To be fair, it must be pointed out that the book does include some hints that may serve as a basis for the necessary discussion: Section 20.6.2.1 on p. 432 states that civilians who participate in fighting lose their protection and becomes legitimate targets. Arguably, this statement is correct with regards to civilians who actually take part in hostilities, and when they do so. Even so, these actions do not entirely change a civilian's status and no carte blanche exists to kill such a civilian in all circumstances. Hence this statement teaches us very little. P. 439 quotes the decision in the case of The Military Prosecutor v. Kassem. This decision ruled that members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine terrorist organization do not deserve the status of prisoners of war since they are non-combatants. However, The Military Prosecutor v. Kassem did not state what their status is. If they are civilians, they can of course be sentenced in criminal proceedings, but they cannot be killed unless criminal excuses and defenses (such as self defense) apply. In section 20.10.4 (at 441) the book discusses the creation of the status of “Illegal Combatants” in the Law for the Incarceration of Illegal Combatants 2002. Sabel criticizes this law, but it is not clear why. Does he consider the very status of illegal combatants to be problematic or is the problem the granting of the semi-legitimate status of illegal combatants to terrorists. Whatever the case, a clear discussion of this issue is lacking.

22 Another name for this area is “New International Law”.

23 See generally: Held, David et al. , Global Transformation: Politics, Economics, and Culture (Stanford, Stanford University Press, 1999)Google Scholar.

24 Zaring, David, “International Law by Other Means: The Twilight Existence of International Financial Regulatory Organizations” (1998) 33 Tex. Int'l L. J. 281Google Scholar.

25 Raustiala, Kal, “The Architecture of International Cooperation: Transgovernmental Networks and the Future of International Law” (2002) 43 Virginia L. Rev. 1Google Scholar.

26 Benvenisti, Eyal. “Exit and Voice in the Age of Globalization” (1999) 98 Mich. L. Rev. 167CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Slaughter, Ann-Marie, “Government Networks: The Heart of the Liberal Democratic Order” in Fox, George et al. , eds. Democratic Governance and International Law (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2000) 199CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Koh, Harold H., “Bringing International Law Home” (1998) 35 Hous. L. Rev. 623Google Scholar.

27 This “Washington Consensus” is of course very ideological at its core. The point is that it manages to establish itself as non-political, and has therefore managed to evade any serious political or public discussion about its core values. The anti-globalization movement has made an attempt to uncover and question these values, but has had, as of yet, only a marginal effect in terms of actual changes in policy. The only policy that has actually undergone any substantial revision is in the area of trade and environment relations. Petersmann, Ernest-Ulrich, “Time for a United Nations Global Compact for Integrating Human Rights into the Law of Worldwide Organizations” (2002) 13 Ear. J. Int'l L. 621CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

28 Finnemore, Martha and Sikkink, Kathryn, “International Norm Dynamics and Political Change” (1998) 52(4) Int'l Org. 887CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

29 Reich, Arie, “From Diplomacy to Law: The Juridicization of International Trade Relations, the Framework of the GATT, and Israel's Free Trade Agreements,” (1999) 22 Iyunei Mishpat 351 [in Hebrew]Google Scholar.

30 For example, one of the hallmarks of the Clinton administration was tying any progress in economic relations between the US and China with changes in human rights practises within China. As a result, a relatively professional matter like trade relations has been made one of the most political in American foreign policy. Foot, Rosmeary, Rights Beyond Borders: The Global Community and the Struggle over Human Rights in China (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2000)CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

31 Israel has added some disputes with international law that are not connected directly with human rights or humanitarian law. Such is especially the case with the application of Israeli domestic law to the Golan Heights (almost certainly an occupied territory according to most international lawyers) and Eastern Jerusalem (almost certainly the same).

32 For an exhaustive discussion of Israel's human rights violation in the territories see: Kretzmer, David, The Occupation of Justice: The Supreme Court of Israel and the Occupied Territories (New York, 2002)Google Scholar see also Sfard, Michael, “International Litigation in the Domestic Court” (2003) 15 HaMishpat 73 [in Hebrew]Google Scholar.

33 But not exclusively so. Others, too, have claimed that certain international agreements are made especially in order to condemn Israel. Such a claim was made with regards to the First Protocol to the Fourth Geneva Convention, relating to non-international armed conflicts. See: Curtis, Michael, “International Law and the Territories,” (1991) 32 Harv. J. Int'l L. 457Google Scholar. A similar suggestion was made about the inclusion of transfer of population from the occupier to occupied territories as a war crime in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. See Shani, Y., “Israel on the Bench: Implications of the Entry into Force of the Rome Statute to Israel” (2003) 15 HaMishpat 28, at 32Google Scholar. [in Hebrew]

34 The International Conference against Racism in Durban was hijacked in 2001 by anti-Israeli groups.

35 Lapidot, Ruth, “International Law in Domestic Law” (1990) 19 Mishpatim 807 [in Hebrew]Google Scholar

36 For a similar critique of the Israeli dualistic system, albeit for different reasons, see: Benvenisti, Eyal, “The Implications of Consideration of Security and Foreign Relations on the Application of Treaties in Israeli Law” (1992) 21(2) Mishpatim 221 [in Hebrew]Google Scholar.

37 Axelrod, Robert, The Evolution of Cooperation (New York, Basic Books, 1984)Google ScholarPubMed.

38 Haas, Peter M., “Introduction: Epistemic Communities and International Policy Coordination” (1992) 46 Int'l Org. 1CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

39 Hathaway, Oona A., “Do Human Rights Treaties Make a Difference?” (2002) 111 Yale L J. 1365CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

40 Sykes, Alan O., “Regulatory Protectionism and the Law of International Trade” (1999) 66 U. Chic. L. Rev. 1CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

41 Keohane, Robert, After Hegemony (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1984)Google Scholar.

42 For a general description of these developments see: Hudec, Robert E., “The New WTO Dispute Settlement Procedure: An Overview of the First Three Years” (1999) 8 Minn. J. Global Trade 1, 7–8Google Scholar.

43 Hathaway, supra n. 39.

44 International Convention for Protection of Civil and Political Rights, Articles 28–41.

45 Convention for the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, Article 17.

46 Buergenthal, Thomas, “The Human Rights Committee” in Alston, P., ed. The United Nations and Human Rights (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 2000) Chap. 10Google Scholar.

47 The most sophisticated model of international human rights laws assumes that domestic changes will only occur when supported by strong domestic groups. Risse, Thomas et al. “The Socialization of International Human Rights Norms into Domestic Practices” in Risse, Thomas et al. , eds. The Power of Human Rights: International Norms and Domestic Change (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1999) 1–38CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

48 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (1998) 37 I.L.M. 999Google Scholar.

49 Hirsch, Michelle and Kumps, Nathalie, “The Belgian Law of Universal Jurisdiction Put to the Test” (2003) 35 Justice 20Google Scholar.

50 Zilbershats, Yafa, “The Role of International Law in Israeli Constitutional Law” (1997) 4(1) Mishpat Umishal 47 [in Hebrew]Google Scholar.

51 Reisman, W. Michael, “The Lessons of Qana” (1997) 22 Yale J. Int'l L. 381, 395–397Google Scholar.

52 Arguably, the transfer of all Arabs from the territories could minimize the risk to Israeli life. Yet, we reject this policy as morally and politically unacceptable. On the other hand, we think of a deportation of one or several terrorists as acceptable, although we know that it might arouse international criticism.