No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 16 February 2016

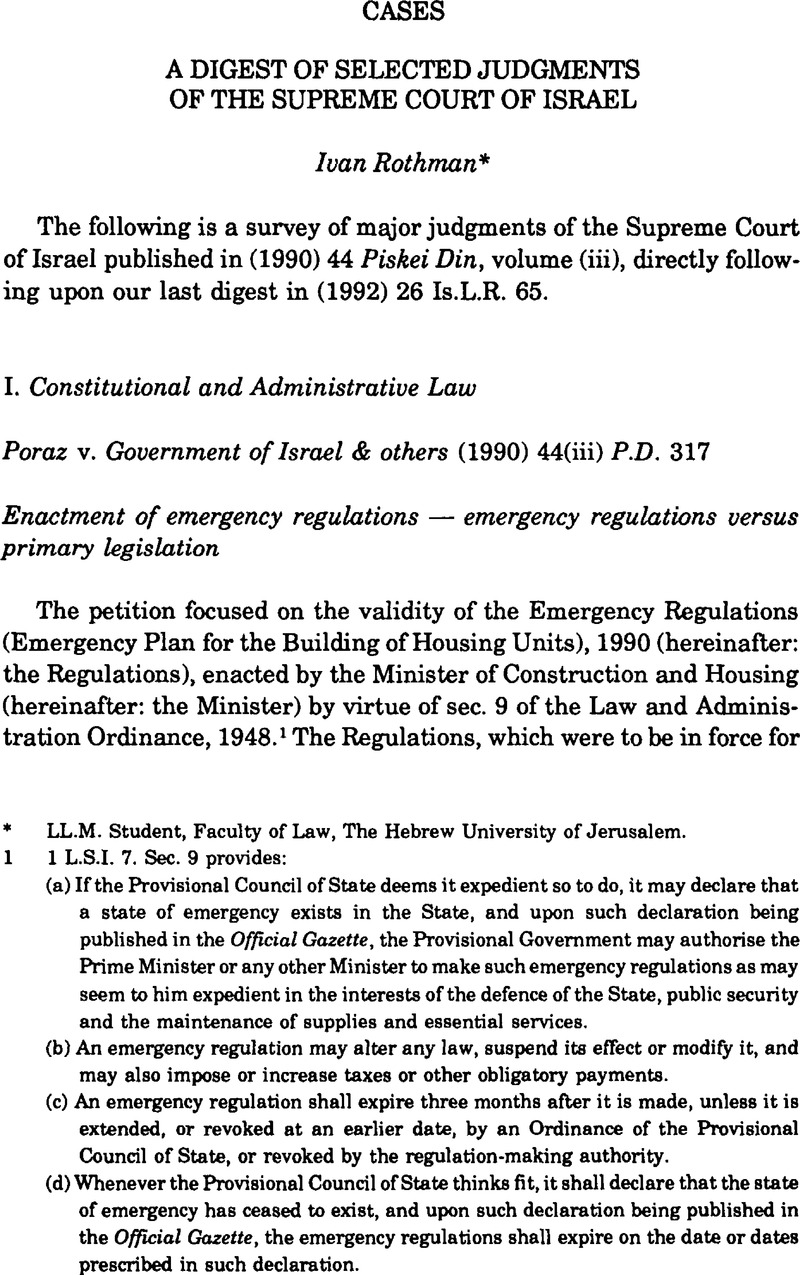

1 L.S.I. 7. Sec. 9 provides:

(a) If the Provisional Council of State deems it expedient so to do, it may declare that a state of emergency exists in the State, and upon such declaration being published in the Official Gazette, the Provisional Government may authorise the Prime Minister or any other Minister to make such emergency regulations as may seem to him expedient in the interests of the defence of the State, public security and the maintenance of supplies and essential services.

(b) An emergency regulation may alter any law, suspend its effect or modify it, and may also impose or increase taxes or other obligatory payments.

(c) An emergency regulation shall expire three months after it is made, unless it is extended, or revoked at an earlier date, by an Ordinance of the Provisional Council of State, or revoked by the regulation-making authority.

(d) Whenever the Provisional Council of State thinks fit, it shall declare that the state of emergency has ceased to exist, and upon such declaration being published in the Official Gazette, the emergency regulations shall expire on the date or dates prescribed in such declaration.

2 S.H. 1323, p. 66.

3 On the question of implied repeal, and the presumption against such repeal, reference was made to: Ramat-Gan Municipality v. Attorney General (1962) 16 P.D. 161 and Poraz v. The Mayor of Tel-Aviv-Yaffo & others (1988) 42(ii) P.D. 309.

4 These three elements were initially stressed by Barak J. in Rozen & others v. Minister of Trade, Commerce and Tourism & others (1979) 33(iii) P.D. 281, with regard to the exercise of the authority granted under sec. 3 of the Commodities and Services (Control) Law, 1957 (12 L.S.I. 27). The term “essential activity” is defined in sec. 1 of this Law as, inter alia, “any activity which a Minister regards as essential to the … absorption of immigrants … ” In Kloffefer Nava v. Minister of Education and Culture (1984) 38(iii) P.D. 233 the same three-fold test was applied in the context of sec. 9 of the Ordinance.

5 19 L.S.I. 330.

6 The petition did not address the topical and controversial question concerning the legal validity of such agreements. Furthermore, the factual background to the petition is set out by Shamgar P. in only very brief and general terms, and is not of major significance in understanding the issues raised by the petition.

7 The government in Israel emerges from within the Israeli parliament, the 120 member Knesset, and its continued existence depends on the support of a majority within the Knesset. Hence, to establish a government, one of the parties, or a coalition of such parties, must command a majority within the Knesset. In this context, mention should be made of sec. 15 of the Basic Law: The Government, which provides: “When a Government has been formed, it shall present itself to the Knesset, shall announce the basic lines of its policy, its composition and the distribution of functions among the Ministers, and shall ask for an expression of confidence. The Government is constituted when the Knesset has expressed confidence in it, and the Ministers shall thereupon assume office” (22 L.S.I. 259). The electoral system is a system of proportional representation based on fixed party lists. Voters vote for a list of party representatives chosen by the party itself. The number of seats which a party is then allotted within the Knesset is proportional to the number of votes received in the general elections.

8 As Shamgar P. pointed out, no one party has as yet been able to form a government single-handedly.

9 See supra n. 7.

10 27 L.S.I. 48. Sec. 1 of the Law defines a “financing unit” as “an amount designated by the Finance Committee of the Knesset as a financing unit for the purposes of this Law …” Sec. 2 of the Law provides: “(a) Every party group shall, in accordance with the provisions of this Law, be entitled to be financed for — (1) its elections expenses in the election period; (2) its running expenses in every month from the month following the publication of the results of the elections to the Knesset until the month in which the results of the elections to the next Knesset are published, (b) The money for financing shall be paid out of the Treasury …” Sec. 3(a) of the Law provides: “Election expenses shall be financed on the basis of one financing unit per seat obtained by the party group in the elections to the Knesset”. The FC increased the finance unit per seat from 207,000 NIS to 320,000 NIS. In addition, the FC decided that the increase would apply retrospectively to the elections expenses incurred by party groups with respect to the elections to the Twelfth Knesset.

11 S.H. 1266, p. 6.

12 12 L.S.I. 85. Sec. 4 of the Basic Law provides, inter alia: “The Knesset shall be elected by general, national, direct, equal, secret and proportional elections, in accordance with the Knesset Elections Law …”

13 Sec. 4 of the Basic Law continues thus: “This section shall not be varied save by a majority of the members of the Knesset”. This means at least 61 out of the 120 member Knesset.

14 Sec. 46 of the Basic Law (Basic Law: The Knesset (Amendment No. 3) 13 L.S.I. 228) provides: “The majority required by this Law for a variation of section 4,44 or 45 shall be required for decisions of the Knesset plenary at every stage of law-making, except a debate on a motion for the Knesset agenda. In this section, “variation” means both an express and an implicit variation”.

15 The initial decision of the FC — and so the ratifying 1988 Law — was viewed as contravening the equality provision primarily because of its retrospective effect. The decision altered, retrospectively, the relative rights of the parties entitled to financing, and in this way harmed their equality of opportunity inter se. Barak J. said that if all the competing political groups had known in advance of the FC's decision, they might have planned their electoral campaigns differently. The decision changed the “rules of the game”, thus harming the legitimate expectations of the different parties. He stressed that the decision retrospectively legitimized the unlawful conduct of those parties who — perhaps in the hope that they would subsequently be in a position to validate their conduct through legislation — had exceeded the financing limits in force at the time of the elections. In this way, inequality of opportunity was created between such parties, and those which had remained within the then permissible, lower financial limits.

16 Barak J. and Elon D.P. also differed in opinion with regard to the nature of the FC's authority and decision. Barak J. was of the opinion that in contravening the equality provision, the FC had acted ultra vires. In his view, the FC's decision was tantamount to secondary legislation. As such, the decision was discriminatory and opposed to the purpose of the enabling legislation (i.e., the Law). The decision was, therefore, void. Elon D.P. challenged the view that the FC had been acting in a governmental (i.e., executive) capacity, and that its decision constituted a piece of secondary legislation. In his view, the FC formed part of the legislative branch, being composed of members of this branch. Hence, its decision constituted a kind of “circuitous legislation” on behalf of the Knesset itself, the FC being a kind of “miniature Knesset”.

17 28 L.S.I. 116. Sec. 5 provides: “The contractor shall have a lien on any property delivered to him by the orderer for the carrying out of the work or the rendering of the service, up to the amount due to him from the orderer in consequence of the transaction”.

18 25 L.S.I. 11. Sec. 19 provides: “Where in consequence of the contract the injured party has received any property of the person in breach, which he must return, the injured party shall have a lien on such property to the extent of the sums due to him from the person in breach in consequence of the breach”.

19 31 L.S.I. 238. Sec. 33 provides: “The Authority shall have a lien on all goods in its possession for which any fee or other payment is due to it. The lien shall also vest it with a priority right to collect the debt out of all the proceeds of the sale of the goods in precedence to any other priority right in respect of those goods…”

20 25 L.S.I. 175. Sec. 11(a) provides: “A lien is a right under law to detain movable property as security for an obligation until the obligation is discharged”.

21 Sec. 5 of the Bankruptcy Ordinance (New Version), 1980 (3 L.S.I. [N.V.] 133) defines a “secured creditor” as “a person holding a charge or lien on the property of the debtor or any part thereof as security for a debt due to him from the debtor”; sec. 353 of the Companies Ordinance (New Version), 1983, ((1983) D.M.I. 764) applies bankruptcy laws (including the definition of a “secured creditor”) to the winding up of a company because of insolvency: “In an insolvent company, procedure shall follow the bankruptcy laws applicable to the assets of a person proclaimed to be a bankrupt, as far as connected to the rights of secured and unsecured creditors …”

22 The authorized translation of sec. 33 of the Aerodromes Authority Law (supra n. 19) states that “the Authority shall have a lien on all goods in its possession for which any tax or other payment is due”. It should be noted, however, that the Hebrew noun “reshut”, translated as “possession”, does not necessarily imply actual physical possession. Moreover, case law has interpreted the term “reshut” as implying only control and supervision. In view of the position taken by Goldberg J. concerning the legal consequences of a lien in favour of a tax authority, he did not find it necessary to determine whether the planes — which had been in the actual physical possession of the IAI — had been under the control and supervision of the AA.

23 That the AA was a “secured creditor”, at least technically, followed inexorably from the definition in sec. 1 of the Bankruptcy Ordinance (New Version), 1980, see supra n. 21.

24 As Goldberg J. went on to explain, by virtue of sec. 33 of the Aerodromes Authority Law, which constituted a special provision (i.e., a lex specialis), the status of the AA in liquidation proceedings regarding priorities would not be determined by the (less favourable) provisions of sec. 354 of the Companies Ordinance (New Version), 1983, which set down the ordinary and general rules of priority in liquidation. Hence, despite the provisions of sec. 354, the AA would, for example, take priority in liquidation proceedings over employees of the company in liquidation.

25 As further support for his conclusion that the legislator had not generally intended to grant tax authorities priority over secured creditors, Goldberg J, referred, inter alia, to sec. 12A of the Taxes (Collection) Ordinance. He noted that the view according to which the sec. 33 lien resulted in the AA becoming a secured creditor, with priority over pledgees, would render certain provisions of sec. 12A nugatory.

26 Supra n. 20.

27 Sec. 4 provides:

“(a) Where movable property of one person becomes joined or mixed with movable property of another to such degree that they cannot be identified or separated or that their separation would involve unreasonable damage or expense … the joined property shall be owned by such persons in common in the ratio of the value of their respective property immediately before the joining.

(b) If the property of one is the main property and the property of the other subordinate, the ownership of the subordinate property shall pass to the owner of the main property, who shall pay to the other person the amount of the value accruing to him by the acquisition of the subordinate property”.

28 21 L.S.I. 44. Sec. 5 provides: “Where movable property pledged while in the possession of the pledgor has been deposited as specified in section 4(2) or the pledge thereof has been registered as specified in section 4(3), the pledge shall be effective in all respects even if the pledgor was not the owner of the property or was not entitled to pledge it, provided that the creditor acted in good faith and the property came into the hands of the pledgor with the sanction of the owner thereof or with the sanction of a person entitled to have possession thereof.

29 Under Israeli law a creditor holding a pledge in respect to assets owned by a company must, in order to perfect his security, register the pledge in the Companies Registrar. No statutory obligation exists obliging him to also register his pledge in the Pledges Registrar. Hence, a subsequent, potential creditor's primary obligation is to check the Companies Registrar. Goldberg J. held, therefore, that failure by such a creditor to check the Pledges Registrar would not, in itself, vitiate the good faith required of him under sec. 5 of the Pledges Law.

30 The term “scheme” is defined in the Law as “any of the schemes dealt with in Chapter Three” (19 L.S.I. 330). Chapter Three of the Law deals with a number of different planning schemes, including national outline schemes, local outline schemes and detailed schemes.

31 Planning and Building (Amendment No. 20) Law, 1982 (37 L.S.I. 25).

32 The term “long-term tenancy” is defined in sec. 3 of the Land Law as “a lease for a period of more than twenty-five years” (23 L.S.I. 284).

33 The provisions governing the payment of such a charge are laid down in the Third Schedule of the Law: Planning and Building (Amendment No. 18) Law, 1981 (35 L.S.I. 214).

34 Sec. 3 of the Land Law, supra n. 32 defines the term “lease” as follows:

“The lease of immovable property is the right, granted in consideration of a rent, to possess and use it otherwise than permanently. A lease for a period of more than five years shall be called a ‘tenancy’ …”

35 The term “key money” refers to sums paid by a protected tenant to the property owner in order to obtain rights and the status of a protected tenant.

36 2 L.S.I. [N.V.] 14. Sec. 35 of the CWO provides: “Where a person does some act which in the circumstances a reasonable prudent person would not do, or fails to do some act which in the circumstances such a person would do … then such act or failure constitutes carelessness and a person's carelessness as aforesaid in relation to another person to whom he owes a duty in the circumstances not to act as he did constitutes negligence. Any person who causes damage to any person by his negligence commits a civil wrong”.

37 By contrast, the VCL, 29 L.S.I. 311, instituted a system of no fault, strict liability for road accidents. Sec. 2 of the VCL provides, inter alia: “(a) A person using a motor vehicle … shall compensate a victim for bodily damage caused to him in a road accident in which the vehicle was involved … (b) The liability is absolute and entire and it shall be immaterial whether or not there was fault on the part of the driver and whether or not there was fault or contributory fault on the part of others”.

38 In this part of his judgment Shamgar P. drew heavily on a number of relevant, previous rulings, including: Algavish v. State of Israel (1976) 30(ii) P.D. 561; Va'aknin v. Local Council, Beit Shemesh & others (1983) 37(i) P.D. 113; Ya'ari & others v. State of Israel (1981) 35(i) P.D. 769.

39 Shulmann & others v. Zion Insurance Co. Ltd. (1988) 42(ii) P.D. 844, at 862-4, 866-67 (per Barak J.).

40 Drayton, , The Laws of Palestine (1933) vol. 1, p. 356, at 358Google Scholar. Sec. 6(1) provides: “The Supreme Court, the Court of Criminal Assize, a Special Tribunal constituted under Article 55 of the Palestine Order-in-Council, 1922, the District Court and the land court shall have power to enforce by fine or imprisonment obedience to any order issued by them directing any act to be done or prohibiting the doing of any act”.

41 L.S.I. Special volume. Sec. 287 provides: “A person who disobeys a direction duty issued by any court, officer or person who acts in an official capacity and is authorised in that behalf is liable to imprisonment for two years” (at 78).

42 Sec. 52 of the Penal Law provides, inter alia: “(a) Where the court imposes a penalty of imprisonment, it may, in the sentence, direct that the whole or part of such penalty shall be conditional, (b) A person sentenced to conditional imprisonment shall not undergo his penalty unless, within a period prescribed in the sentence being not less than one year and not more than three years (hereinafter referred to as the ‘period of suspension’), he commits one of the offences designated in the sentence … and is convicted of such offence either within or after the period of suspension” (at 23).

43 4 L.S.I. 117. Sec. 10 of the Fallen Soldiers Law contains a number of provisions governing the various rights of bereaved parents to receive a pension.

44 30 L.S.I. 119.

45 Pensions Officer v. Shalush (1980) 34(i) P.D. 740; Pensions Officer v. R. Levi and others (1984) 38(iii) P.D. 830; Pensions Officer v. Allon (1988) 42(ii) P.D. 821. Two other related cases surveyed by Bach J. were not published.

46 13 L.S.I. 315.

47 Sec. 1 of the Invalids Law defines the term “invalidity” as:

“ … the loss of the faculty to perform an ordinary action, whether physical or mental, or the diminution of such a faculty, with which a discharged soldier is afflicted as a result of one of the following occurring in the period of his service in consequence of his service: (1) illness; (2) aggravation of illness; (3) injury”.

48 Pensions Officer v. Bosani (1970) 24(i) P.D. 637.

49 Bach J. refers here to the dissenting opinion delivered by H. Cohn J. (as he then was) in Bosani, ibid.