No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 February 2016

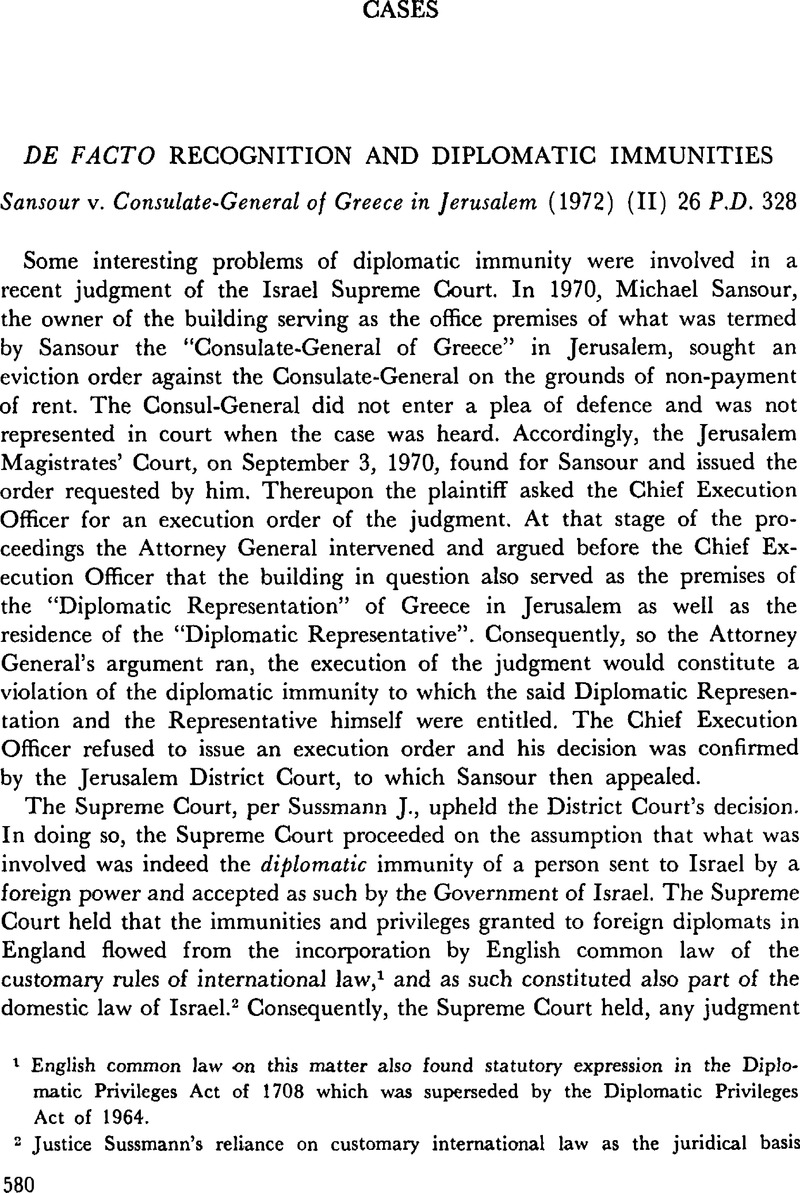

1 English common law on this matter also found statutory expression in the Diplomatic Privileges Act of 1708 which was superseded by the Diplomatic Privileges Act of 1964.

2 Justice Sussmann's reliance on customary international law as the juridical basis of diplomatic immunities in Israel is explained by the fact that in Israel—as in England—treaties do not become automatically part of domestic law and their effect on the domestic plane depends on a specific act of transformation. (See Custodian of Absentee Property v. Samra (1955) 10. P.D. 1825; (1955) 22 International Law Reports 5). Thus, in the absence of an Israel statute on diplomatic privileges and immunities (see infra n. 38), Israel's ratification, on August 11, 1970, of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations of 1961 cannot be regarded by an Israel court as binding on the domestic plane. Customary international law, on the other hand, is regarded in Israel as part of the law of the land, for, by virtue of Article 46 of the Palestine Order-in-Council of 1922 (Drayton, , Laws of Palestine, vol. III, p. 2580Google Scholar) and sec. 11 of the Law and Administration Ordinance (1948) 1 L.S.I. 9, Israel law follows English common law on this matter. See Stampfer v. Attorney-General (1956), 10, P.D. 5; (1956) 23 International Law Reports 284.

3 According to Oppenheim-Lauterpacht, “the Municipal Law of every State is obliged to possess rules granting the necessary privileges to foreign diplomatic envoys”. Oppenheim-Lauterpacht, , International Law (8th ed., 1955) vol. I, p. 45.Google Scholar

4 See Re Suarez [1918] 1 Ch. 176.

5 Emphasis added.

6 Chen, , The International Law of Recognition (1951) 101.Google Scholar

7 Ibid., 101–102. It is worth pointing out in this connection that, according to a subsequent statement made by the United States representative in the Security Council, the de jacto recognition by the United States applied to the Government of Israel, while the State of Israel had been granted full and immediate recognition by the United States from the date of its inception. On December 2, 1948, Mr. Philip Jessup, then Deputy United States Representative to the United Nations, told the Security Council that “following the proclamation of the independence of Israel on May 14, 1948, the United States extended immediate and full recognition to the State of Israel and recognized the provisional Government of Israel as the de facto authority of the new state”. (Quoted in Whiteman, , Digest of International Law (1963) vol. II, p. 169Google Scholar). On the American recognition of Israel see also Brown, , “The Recognition of Israel” (1948) 42 A.J.I.L. 620.Google Scholar

8 Indirect support for this view may be found in the definition of a “permanent diplomatic mission” in Article 1(b) of the Convention on Special Missions (U.N. Doc. A/7630, 99) where it is defined as “a diplomatic mission within the meaning of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations”. Article 1 (b) of the Draft Articles of Special Missions prepared by the International Law Commission defined a permanent diplomatic mission as “a diplomatic mission sent by one State to another State and having the characteristics specified in the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations”. Report of the International Law Commission on the Work of its 19th Session, Yearbook of the International Law Commission 1967, vol. II, p. 348 (emphasis added). In the Commentary to article 1(b), the Commission refers to “the absence of a definition of permanent diplomatic missions in the 1961 Vienna Convention”. (Ibid.)

9 To be sure, the accreditation of a person put in charge of a diplomatic representation to a person other than the head of the receiving State does not necessarily signify his “irregular” diplomatic status. Thus, article 14(1)(c) of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations of 1961 (which on this matter follows the relevant provision contained in the Regulation of Vienna of 1815 regarding the classification of diplomatic agents) provides that a chargé d'affaires (who is considered a “head of mission” under the Convention) be accredited to the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the receiving State. This stipulation applies to the so-called chargé d'affaires en pied who “is appointed on a more or less permanent footing”. (Report of the International Law Commission on the Work of its 10th Session, Yearbook of the International Law Commission 1958, vol. II, p. 94). He is to be distinguished from the chargé d'affaires ad interim who acts provisionally as the head of the mission “if the post of the head of mission is vacant, or if the head of mission is unable to perform his functions”. (Article 19(1) of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations). The latter “does not present any letters of credence; his name is merely notified by the head of mission, or in case he is unable to do so, by the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of the sending State, to the Ministry for Foreign Affairs or some other appropriate authority of the receiving State”. (Ibid.)

10 U.N. Doc. A/7630, 99. For the entry into force of the Convention, 22 ratifications or accessions are required (Article 53). As of November 1972 only 4 States were parties to the Convention (November 1972, U.N. Monthly Chronicle 135).

11 U.N. Doc. A/7630, 99; emphasis added.

12 Report of the International Law Commission on the Work of its 19th Session, Yearbook of the International Law Commission, 1967, vol. II, p. 347Google Scholar; emphasis added.

13 Ibid., 348; emphasis added.

14 Ibid., 347.

15 Waters, , The Ad Hoc Diplomat: A Study in Municipal and International Law (1963), 112.CrossRefGoogle Scholar In light of the definition offered by Waters it is somewhat surprising that in the appendix of his book containing “a representative list of special agents who have been sent on foreign missions by Presidents of the United States” (ibid., 175 ff.), he mentions Mr. James McDonald, head of the United States mission to Israel during the period of the de facto recognition of the Government of Israel by the United States. (Ibid., 178). It should be remembered that Mr. McDonald's mission was not “a specific assignment”, and that he was entrusted with the task of maintaining general diplomatic relations with the Provisional Government of Israel. It would appear that in listing Mr. McDonald among the heads of American special missions, Waters was influenced by the fact that in the official White House statement of June 22, 1948, announcing the establishment of a United States Mission in Israel and of an Israel Mission in the United States, reference was also made to the exchange of “special representatives”. (See Whiteman, op. cit.) Also, Waters may have regarded Mr. McDonald's mission as one of “limited duration”, for the United States Government had declared as early as October 24, 1948, that the Government of Israel would be accorded de jure recognition promptly after the first parliamentary elections in Israel. Indeed, the United States acted accordingly soon after the Knesset elections of January 1949 (see Department of State Bulletin, vol. 20, p. 502) and Mr. McDonald became thereupon the first United States Ambassador to Israel. On special missions in general, see also Bartos, , “Le statut des missions spéciales” (1963) I 108 Recueil des Cours de l'Académie de Droit International, 431–560.Google Scholar

16 Oppenheim-Lauterpacht, op. cit., 136–137.

17 Lauterpacht, , Recognition in International Law (1947) 345–346.Google Scholar

18 Starke, , Introduction to International Law (6th ed., 1967) 141.Google Scholar

19 Ibid., 143.

20 Ibid.

21 Schwarzenberger, , International Law, (3rd ed., 1957) vol. I, p. 198.Google Scholar

22 Ibid., 156.

23 Report of the International Law Commission on the Work of its 10th Session, Yearbook of the International Law Commission 1958, vol. II, p. 105.Google Scholar

24 See supra nn. 16–20.

25 (1922) 38 T.L.R. 260. Krassin was the representative of the Soviet Government appointed under the Anglo-Soviet Trade Agreement of 1921 (114 British and Foreign State Papers, 373), and his immunity was defined in Articles IV and V of the said Agreement, which was subsequently interpreted by the British Foreign Office as connoting recognition de facto of the Soviet Union. (See Luther v. Sagor [1921] 3 K.B. 532).

26 Lauterpacht, op. cit., 344. Lauterpacht's rather cautious interpretation of the Court's decision with regard to the immunities to which Krassin was entitled (the Court held that the status of Krassin was not such as to confer on him immunity from civil process, because his immunity, as defined by the Anglo-Soviet Trade Agreement, was limited to exemption from arrest and search), is explained by the fact that “the language used by both Scrutton and Acton L.JJ. suggests that the question might have been open to doubt if the immunities of M. Krassin had not been defined in the Trade Agreement but had to be deduced from general international law”. (Ibid., n. 5). Chen is even more explicit on this point: “It was the position and function of Krassin, rather than the lack of de jure recognition of his government, which determined, in this case, the scope of his immunity.… The case clearly shows that the Court did not think that the absence of de jure recognition was relevant in determining the question of diplomatic immunity”. (Chen, op. cit., 286).

27 Hansard, , Parliamentary Debates, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 139, col. 2198.Google Scholar

28 Ibid., vol. 404, col. 143.

29 Chen, op. cit., 198 and 286 and the references cited there.

30 See supra n. 25.

31 Hansard, , Parliamentary Debates, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 466, cols. 17–18Google Scholar; reproduced in Whiteman, op. cit., 727–728.

32 See supra n. 16. It is worth noting here that the holding of a diplomatic passport, and the performing of some diplomatic functions, does not appear to result necessarily in a legal obligation by the receiving State to accord diplomatic privileges and immunities to the holder of such passport. See Waters, op. cit., 78–80.

33 Oppenheim-Lauterpacht, op. cit., 765–766. Similarly, O'Connell states that “the Executive … plays the principal role in decision-making with respect to the extent and character of diplomatic immunity.… The tendency in England over the past century has been to subordinate the courts in much of this decision-making to the Executive by means of the Foreign Office certificate, which is conclusive as to whether or not a particular person enjoys diplomatic status”. (O'Connell, , International Law (2nd ed., 1970) vol. II, p. 896).Google Scholar

34 Oppenheim-Lauterpacht, op. cit., 765, n. 4. On the role of the Foreign Office certificate in Britain in general, see Lyons, , “The Conclusiveness of the Foreign Office Certificate” (1946) 23 British Year Book of International Law, 240.Google Scholar

35 See Rosenne, , “The Foreign Office Certificate” (1955) 11 HaPraklit 33et seq.Google Scholar

36 (1953) P.M. 455; (1953) 20 International Law Reports 391.

37 Shababo had been run over and killed in Jerusalem in June 1952 by a car driven by Heilen, a soldier in the Belgian Army on duty with the Belgian Consulate-General in Jerusalem. The action for damages was brought by Shababo's widow against Heilen, as well as against the Consulate-General and the Consul-General, since the car belonged to one of them and was driven on duty at the time of the accident.

38 (1967) Hatza'ot Hok no. 31, p. 33. The Bill was submitted to the Knesset by the Government in November 1967, and after the first reading, it was referred by the Knesset, on May 7, 1969, to the Foreign Affairs and Defence Committee. The Bill had reached the committee stage only when the elections to the Knesset were held in October 1969. Under Israel law, bills lapse upon the holding of parliamentary elections, unless the Government constituted in an incoming Knesset has given notice of its desire that the rule of continuity should apply to a bill which the outgoing Knesset, after the first reading, had referred to one of its committees, provided that such notice by the Government may be rejected by the Knesset. If the rule of continuity has been applied, the incoming Knesset continues to consider the bill from the stage reached by the outgoing Knesset. (Bills (Continuity of Deliberations) Law, (1964) 19 L.S.I. 3). The Government constituted after the Knesset elections of October 1969 did not apply the law on the continuity of deliberations to the Diplomatic and Consular Immunities and Privileges Bill. Cf. sec. 13 of the Israel Bill with sec. 4 of the British Diplomatic Privileges Act of 1964 which states that a certificate by the Executive is conclusive of diplomatic status.