No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 28 February 2019

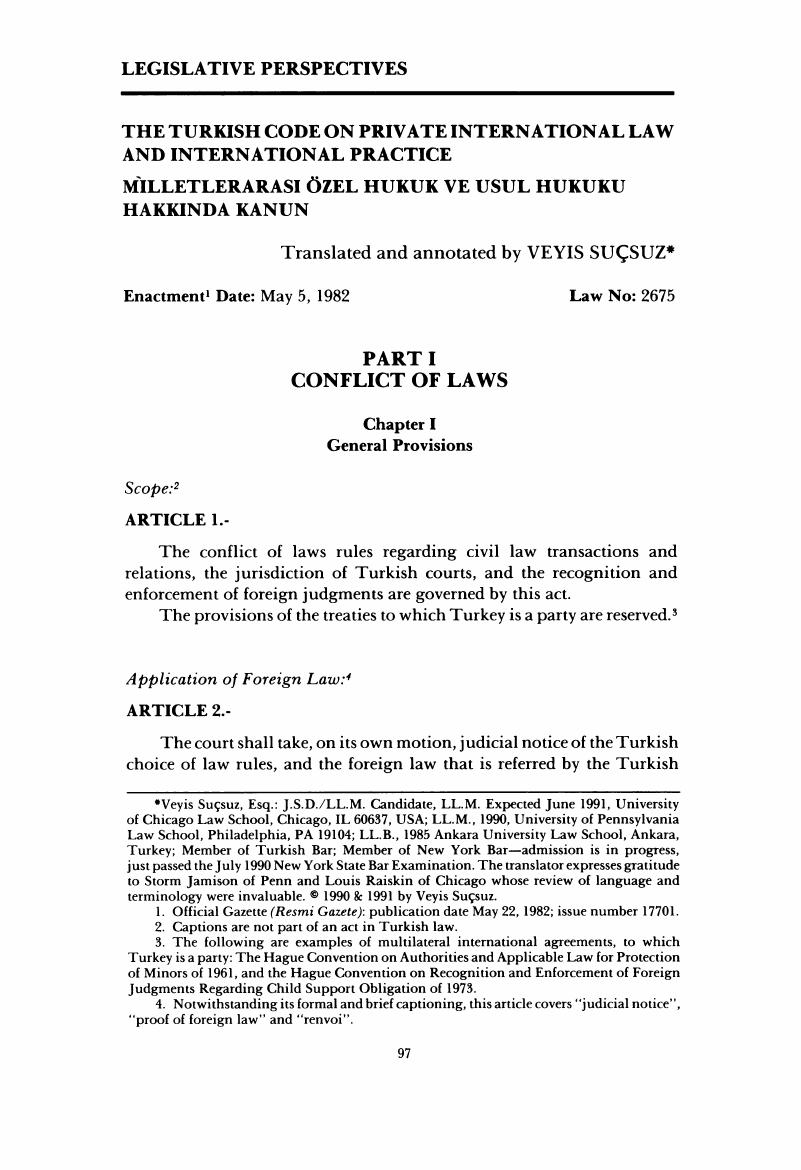

1 Official Gazette (Resmi Gazete): publication date May 22, 1982; issue number 17701.Google Scholar

2 Captions are not part of an act in Turkish law.Google Scholar

3 The following are examples of multilateral international agreements, to which Turkey is a party: The Hague Convention on Authorities and Applicable Law for Protection of Minors of 1961, and the Hague Convention on Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Judgments Regarding Child Support Obligation of 1973.Google Scholar

4 Notwithstanding its formal and brief captioning, this article covers “judicial notice”, “proof of foreign law” and “renvoi”.Google Scholar

5 In Turkish law and practice the court, i.e., judge, must always take judicial notice of all Turkish law, the constitution and the issue of constitutionality, statutes, by-laws and the case that is binding precedent, without pleading of such law by the parties. In practice the counsels for the parties do plead the law and its citations, and they are expected to do so, at least partially. The cause of action, e.g., tort, contract or unjust enrichment, should be pleaded. Generally, the parties need not to be represented by their counsels before Turkish courts, and need not retain an attorney. Cf., Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 44.1, the Uniform Interstate and International Procedure Act, § 4.0.1, and New York Civil Practice Law and Rules, Rule 3016(e). For civil litigation, administration of civil cases, civil procedure and civil evidence see the excellent comparative work of D. Karlen, Civil Litigation in Turkey (1957).Google Scholar

6 That is, first reference is to the “whole law” (including choice of law rules). In other words, the first reference is followed completely, including the referred law's choice of law rules.Google Scholar

7 That may be a third law (transmission) or the forum law (remission).Google Scholar

8 That is, second reference is only to “internal law = substantive law” (not including choice of law rules).Google Scholar

9 Partial renvoi is recognized, i.e., there may be only one remission (or transmission). In other words, whether the result of renvoi is the application of a third law or the forum law, that law finally and decisively governs the issue without further merry-go-round.Google Scholar

10 By ‘domicile’ and ‘residency (residence)’ the law refers to “permanent residence” and “habitual residence”, respectively. See the reference in footnote 16, and cf. P.A. Karrer & K.W. Arnold, eds. & trns., Switzerland's Private International Law Statute of 1987, Pp. 45–49 (Deventer: Kluwer, 1989).Google Scholar

11 Commencement date is usually the filing date, assuming that service of process by the court can be made later through the special mailing procedure. See infra Appendix, p. 37.Google Scholar

12 What is the citizenship of an American in determining the applicable national law in the eyes of this act or before Turkish courts? No special question arises with respect to federal law. When it comes to state law, we need to determine the state citizenship, in other words, domicile, of such U.S. citizen. It can be suggested that the state where the permanent residency (domicile, voluntary and indefinite stay) is established is the state whose law is applicable regardless of the birthplace. Both American practice and Turkish practice support this view since this act regards domicile (permanent residence) as an alternative to citizenship when citizenship is not helpful. Additionally, in American practice state citizenship is the domicile (permanent residence) rather than birthplace, thus state citizenship does not depend on the mere, at least, birthplace. In cases of American soldiers located in military bases in Turkey or American citizens domiciled abroad or in temporary residence in another state, the question might become a little bit more complicated. Cf. Ansay, T., American-Turkish Private International Law, footnote 23, at p. 14 (1966), a caution is in order, this book is mostly outdated.Google Scholar

13 The rules determining domicile and residency are found in the Turkish Civil Code, Articles 19–22. The Turkish Civil Code of 1926 is an identical and complete translation of that of Switzerland (1912) with very few and minor changes. See supra footnote 13.Google Scholar

14 Turkish citizenship is governed by the Nationality Act of 1964, as amended. Multiple citizenships are allowed.Google Scholar

15 Choice of law rules or principles are not limited to this act. A few specific rules may be found in some other statutes or codes. In addition to this act, and relevant bilateral or multilateral international agreements that are presently in force in Turkey. For example, the Turkish Commercial Code of 1957 and Civil Code of 1926. The most important ones are those found in the Commercial Code regarding negotiable instruments, for example, Articles 678–687, 690(1) and 730(21). Those specific choice of law rules concerning negotiable instruments, found in the Commercial Code, are in complete conformity with the “Geneva Convention on Bills and Notes of 1931”. Turkey has not been a party to the said convention, which was signed by her but not ratified. There is no practical need for her being a formal party given the fact that Turkey has adopted the same rules by a subsequent internatal statute (i.e., the Commercial Code). See Ansay, American-Turkish Private International Law, Pp. 43–44 & 28–33 (1966) for commercial paper choice of law rules and intellectual property, respectively.Google Scholar

16 The capacity to have rights and the capacity to act. Cf. Karrer, P.A. & Arnold, K.W., eds. & trns., Switzerland's Private International Law Statute of 1987, p. 58 (1989).Google Scholar

17 See infra footnote 26.Google Scholar

18 Headquarters, place of administration or corporate management.Google Scholar

19 With respect to determination of capacity, in the view of the translator, this rule of capacity should be construed as meaning that the primary applicable law will be the law of the state of incorporation, rather than that of the principal place of business, for the corporations incorporated in a country where there is a federal system with multiple jurisdictions such as the United States of America. For example, the capacity of a Delaware corporation with a principal place of business in the State of New York (assuming both de jacto and de jure principal places of business are in New York) should be governed by Delaware law (incorporation law) first. Then, it should be governed by New York law (law of principal place of business) if Delaware law is inadvertently silent, and the former is relevant. Finally, we might turn to federal law (United States law) as a last source in rare cases such as a case involving the question of whether foreign corrupt practices are within the capacity of the corporation. As a further example, the capacity of a U.S. national bank (national banks -N.A.- are incorporated under federal law but nevertheless their business activity is limited to a certain state or region, e.g., Pennsylvania) should be governed first by federal law (incorporation law). (Surprisingly bank holding companies are incorporated under state laws regardless of the fact that the affiliated bank is a national or state bank).Google Scholar

20 Though maintenance of a spouse is recognized, alimony is unknown in Turkish law.Google Scholar

21 In other words, the demand of permanent maintenance orders are governed by the law controlling the divorce or separation.Google Scholar

22 In New York, it is commonly known as Filiation Orders and Filiation Proceedings.Google Scholar

23 In Swiss and Turkish law “property rights = real rights” include: ownership, possession, mortgage, lien, pledge, easements, servitude, land and deed registration, conveyance, and certain types of ownership tenancies; but excludes landlord-tenant obligation. Cf. Karrer, P.A. & Arnold, K.W., eds. & trns., Switzerland's Private International Law Statute of 1987, Art. 103, p. 102 (1989).Google Scholar

24 The translator interprets “last” as being “previous”. However, one may argue that “last” means “present” here. Both ways of reading have merits. A research relating to legislative history or purpose is necessary. Cf. Karrer, P.A. & Arnold, K.W., eds. & trns., Switzerland's Private International Law Statute of 1987, Art. 103, p. 102 (1989).Google Scholar

25 By “center-of-gravity performance”, the “main performance” is meant.Google Scholar

26 Center of Gravity Theory: This theory involves grouping of the various contacts the case has with the related jurisdictions. All of the relevant contacts are considered and the law of the place having the most dominant relationship or/and biggest number of contacts (e.g., place of making, place of defendant's performance, residence of the parties, etc.) is chosen as the controlling law, and is applied to the case. This theory, also called the ‘grouping of contacts', is usually applied in contract cases, and regarded as precursor of the ‘most significant relationship test'. It is criticized as being mechanical, and is not much followed today.Google Scholar

27 The Most Significant Relationship Test: This test, being under the influence and following the path of the famous “interest analysis”, approaches the choice of law on an issue by issue instead of case by case basis. That is, in each case multistate or international contacts regarding the substantial issues are separated, and the law of the state or country having the most significant relationship is applied to each issue. This modern test rejects the traditional method of determining the applicable law to all substantial issues of a case from the stand point of a single dominant contact or factor, usually territorial, of such case. In other words, the law applicable to each issue is determined separately. This is the approach adopted by Restatement (Second) Conflict of Laws (1971). According to the Restatement (Second), § 6, the principles to be considered in determining and applying the law that has the most significant relationship to the issue or case are: i-) the needs of the interstate and international system, ii-) policy of the forum, iii-) policies of interested states in the issue or case, iv-) the protection of justified expectations, v-) policies underlying the particular field or rule of law, vi-) certainty, predictability and uniformity, vii-) ease in the determination of the law to be applied.Google Scholar

28 See the supplementary note in regard to Turkish venue rules at the end of the text, infra, Appendix, p. 35 & Pp. 37–40.Google Scholar

29 In Turkish and Swiss law, “personal law (rights of personality, rights inherent to a person)” issues include: change of name, defamation, reputation, capacity, death, birth, age determination, official personal records registry involving family, legitimacy and adoption, birth certificate, marriage and divorce, infancy and incapacity. Capacity includes: age of majority, competence, spendthrift and a married person's capaciy. Cf. Karrer, P.A. & Arnold, K.W., eds. & trns., Switzerland's Private International Law Statute of 1987, p. 57(1989).Google Scholar

30 In the following cases, the reciprocity requirement of this act should be deemed to be satisfied: a-) If Turkish parties are exempt (whether by comity or by an express domestic act or by treaty) from similar bond requirements and restrictions in suits in the country of such foreigner seeking enforcement in Turkey. However, the existence of an express internal statute or a treaty is strongly advised in this context since the proof of the practice or comity relatively may be difficult. b-) In the alternative, if there exist no restrictions or similar bond requirements for any foreign or non-resident party based on non-citizenship or non-residency in suits in the country of such foreigner seeking enforcement in Turkey (i.e., an equal or uniform treatment of citizens and non-citizens). Cf. the reciprocity requirement of Article 38 and its satisfaction in the context of the enforceability of foreign arbitral awards.Google Scholar

31 As in the United States of America, final here should mean “conclusive and on the merits, and enforceable where rendered”.Google Scholar

32 This does not mean that foreign penal judgments can be enforced. For example, if in a country murder (criminal law) and wrongful death (civil damages) could be tried by the same court and at the same time, the enforcement of only the part of holding that concerns “civil damages to victim” may be demanded. Other examples may be: joint trial of criminal adultery and civil adultery (civil damages, and/or divorce, and/or custody); grant of divorce in a criminal case where one spouse was sentenced to 8 years or more, for example, of jail term; criminal bigamy and civil declaration of nullity for the second marriage. Examples are just for illustration and explanation purposes, and are not intended to present or explain existing Turkish law.Google Scholar

33 The “Civil Court of First Instance” is also the court of the general civil jurisdiction (original & trial). This court is for non-small cases, and in many cases the ‘amount in controversy’ requirement applies.Google Scholar

34 “Simple procedure” is one of the several court procedures to be followed at trial level. The closest examples in America would be “small claims procedure”, “procedure of actions at law”, “procedure of actions in equity” or “different rules of different level courts” etc. However, the word “simple = basic” does not necessary mean that this procedure is simpler or the main procedure. See the Civil Procedure Code.Google Scholar

35 Decree or holding.Google Scholar

36 There is a special code for collection, execution or enforcement or satisfaction or foreclosure of all civil judgments, liens, mortgages and commercial paper. This code covers all bankruptcy proceedings, debtor's rights and creditor's rights, and summary judgment proceedings for commercial paper. It is called Icra ve flas Kanunu (Turkish Code of Execution and Bankruptcy of 1929, as amended in 1965 and later), and is based on the Swiss Federal Code of 1889.Google Scholar

37 The rules of civil courts and the rules of civil procedure are embodied in the Civil Procedure Code.Google Scholar

38 Recognition has a special purpose other than enforcement. Recognition determination does not entitle a judgment to be enforced, executed or satisfied. For instance, a divorce decree given in absence of a spouse who is missing can be recognized though it may not be granted an enforcement order. This is not recognition in essence, and one might call it “confirmation”.Google Scholar

39 Turkish law citations are conducted in the following manner: 1) Statute citations: Enactment date and law number without the title (name of the act) are sufficient. However, some well known acts, esp. codes, e.g., “Civil Code”, should be cited just by title (that is “Civil Code”). This act (code) should be cited by law number and date (with or without title). 2) In the citations of articles (sections), paragraphs or subparagraphs, arabic numericals should be used. For example, “Article 3” is for Article III, “Article 8(4)” is for the last -fourth- paragraph of Article VIII, “Article 44(1)(b)” is for the second subparagraph - b- of the first paragraph, and “Article 44(2)” is for the second paragraph of Article 44—the paragraph starting with “The court in … “.Google Scholar

40 See Ansay, T., American-Turkish Private International Law, p. 79 (1966) for the translation of this repealed law.Google Scholar

41 The publication date in the Official Gazette was May 22, 1982, and therefore the statute became effective on November 22, 1982.Google Scholar

42 In this translation of The Turkish Code on Private International Law and International Practice (Milletlerarasi Özel Hukuk ve Usul Hukuku Hakkinda Kanun), the English language legal terms are usually taken from American law. Moreover, the terms of New York State law are given preference over synonyms or other similar phrases, e.g., distribute(s).Google Scholar

43 This act and the information provided herein are current as of the Summer of 1990.Google Scholar