No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 17 January 2008

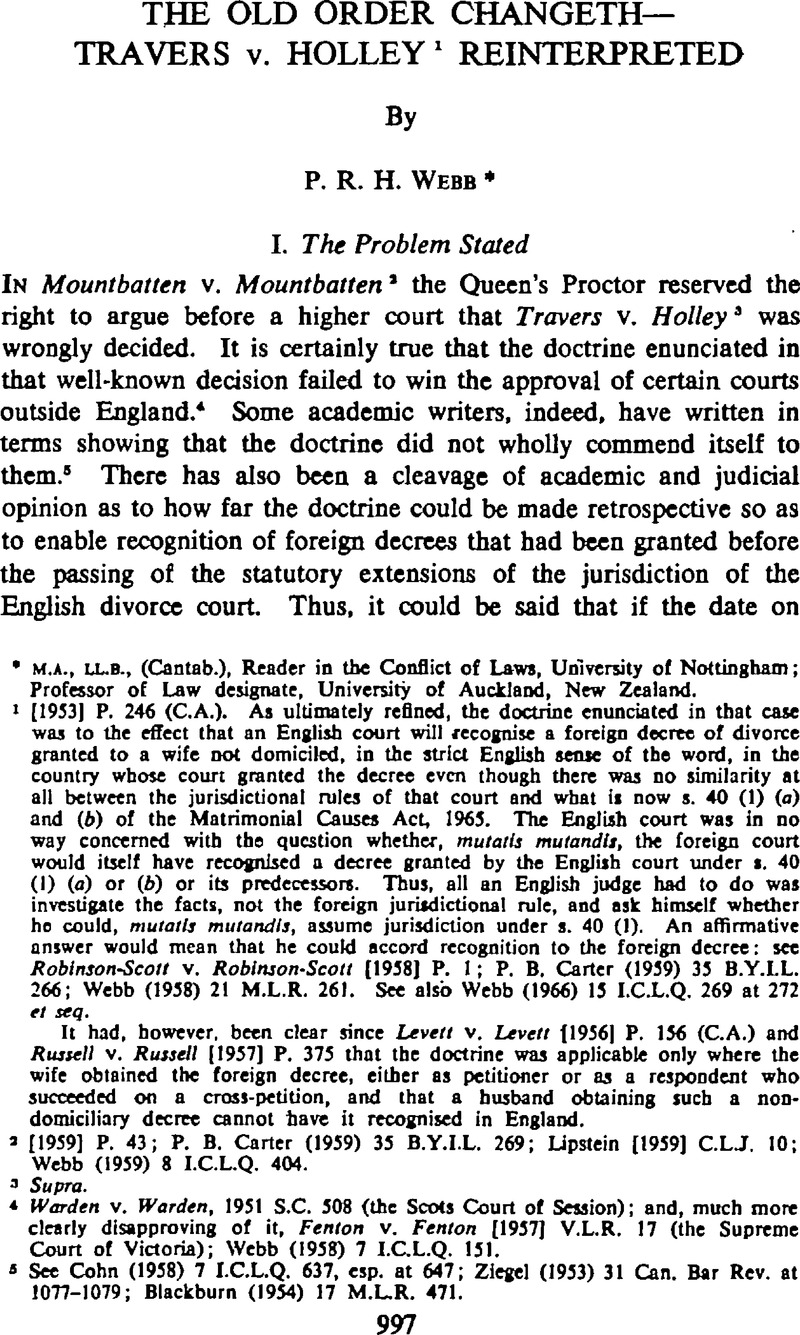

1 [1953] P. 246 (C.A.). As ultimately refined, the doctrine enunciated in that case was to the effect that an English court will recognise a foreign decree of divorce granted to a wife not domiciled, in the strict English sense of the word, in the country whose court granted the decree even though there was no similarity at all between the jurisdictional rules of that court and what is now no similarity at all between the jurisdictional rules of that court and what is now s. 40 (1) (a) and (b) of the Matrimonial Causes Act, 1965. The English court was in no way concerned with the question whether, mutatis mutandis, the foreign court would itself have recognised a decree granted by the English court under s. 40 (1) (a) or (b) or its predecessors. Thus, all an English judge had to do was investigate the facts, not the foreign jurisdictional rule, and ask himself whether he could, mutatis, mutandis, assume jurisdiction under s. 40 (1). An affirmative answer would mean that he could accord recognition to the foreign decree: see Robinson-Scott v. Robinson-Scott [1958] P. 1: P. B. Carter (1959) 35 B.Y.I.L. 266. Webb (1958) 21 M.L.R. 261. See also Webb (1966) 15 I.C.L.Q. 269 at 272 et seq.

It had, however, been clear since Levett v. Levett [1956] P. 156 (C.A.) and Russell v. Russell [1957] P. 375 that the doctrine was applicable only where the wife obtained the foreign decree, either as petitioner or as a respondent who succeeded on a cross-petition, and that a husband obtaining such a non-domiciliary decree cannot have it recognised in England.