In response to the 2014–2016 West Africa Ebola virus disease (EVD) epidemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) developed a tiered network of treatment facilities with high-level isolation capabilities for safely managing patients with EVD in the United States. 1 Overall, 56 hospitals were designated as Ebola treatment centers (ETCs); 1 hospital in each of the 10 US Department of Health and Human Services (DHSS) regions was later selected as a Regional Ebola and Other Special Pathogen Treatment Center to further enhance domestic capacity to care for patients with EVD or other high-consequence infectious diseases (HCIDs). 2

Following designation, federal funding streams supported ETC infrastructure investment, staff recruitment and training, clinical resources, and development of other high-level isolation capabilities. However, previous assessments by our team found that despite significant financial investments in 2014–2015, Reference Herstein, Biddinger and Kraft3 designated units reported challenges in sustaining preparedness levels as the West Africa EVD epidemic was declared over in 2016 and attention and federal funding for HCID preparedness waned. Reference Herstein, Biddinger and Gibbs4,Reference Herstein, Le and McNulty5 By early 2019, at least 4 ETCs had decommissioned their unit and high-level isolation capabilities. Reference Herstein, Le and McNulty5 Nearly all ETCs previously reported federal funding as their primary funding stream and a leading factor in sustaining high-level isolation capabilities. Reference Herstein, Le and McNulty5 Despite this reliance, federal hospital preparedness program (HPP) funding for all but the 10 regional treatment centers expired in May 2020. 6 Although COVID-19 supplemental funding has been allocated as potential temporary funding for these ETCs, and although states can elect to allocate state HPP funding to support state-designated ETCs, the status of most designated ETCs since HPP funding expiration is unknown.

HPP funding expiration for these facilities came amid a global pandemic that exposed vulnerabilities in hospital biopreparedness. Although COVID-19 is not considered a disease warranting high-level isolation care, its emergence as an unknown, novel disease positioned ETCs as the cornerstone of hospital and local preparedness. Reference Flinn, Hynes, Sauer, Maragakis and Garibaldi7–10 Our primary aim was to follow-up on our previous assessments of designated ETCs to determine ongoing sustainability, including how HPP funding expiration has affected the ability of hospitals to maintain ETC capabilities and, for units that no longer maintain those capabilities, reasons for decommissioning. We also sought to identify how the high-level isolation capabilities that ETCs invested in affected hospital, local, and regional COVID-19 readiness and response.

Methods

In February 2021, a link to an electronic survey was sent to all 56 originally designated ETCs, including the 10 regional treatment centers. The 4 hospitals that had previously reported in our assessments that they were no longer an ETC were also included, because we wanted to understand the reasons their unit was decommissioned. The survey was emailed to representatives from each facility and collected using Qualtrics software (SAP, Provo, UT). Data were exported and analyzed using descriptive statistics in an electronic spreadsheet (Excel, Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Qualitative data were coded using open coding; codes were collated into initial themes using content analysis; and themes were reviewed and defined through an iterative process.

The survey was structured into 2 sections: operational sustainability and role in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) response (Supplementary Material online). Using skip logic, the latter was not made available to units that had decommissioned before 2020. The survey included both multiple-choice questions and open-ended qualitative questions. The sustainability section queried units on whether they still had the capability to provide HCID care. Those that did not were asked reasons for decommissioning. Units that maintained capabilities were asked about funding sources, annual expenses, and the intent to continue ETC designation. In the second section, ETCs were asked how their capabilities affected unit, hospital, and local readiness and response to COVID-19 through multiselection options. ETCs were also asked to describe capabilities they had to rapidly develop as well as capabilities they had developed but never utilized. The survey ended with 3 qualitative questions for ETCs to share lessons learned and best practices. The survey was open for 60 days. Also, 2 reminder e-mails were sent to nonrespondents to encourage completion. The University of Nebraska Medical Center Institutional Review Board declared the study exempt from review (no. 0922-20-EX).

Results

Overall, 37 ETCs (66%) responded; 32 completed the survey, and 5 only responded with hospital name and whether the hospital maintains high-level isolation capabilities. Respondents included institutions from all 10 DHHS regions (Table 1). Also, 33 hospitals (89% of those responding) reported that they still had the intent and capability to serve as an ETC for care of patients with EVD and other HCIDs requiring similar specialized isolation.

Table 1. Geographic Distribution of Responding Ebola Treatment Centers (N = 37) a

a States listed by postal abbreviation.

Facilities that have decommissioned

Moreover, 4 hospitals reported they no longer maintained high-level isolation capabilities, including 2 which reported they had been decommissioned in spring 2019 and 1 which was decomissioned in summer 2020. Therefore, these 3 had not been identified in our prior assessments. The other facility decommissioned its unit and capabilities in 2015 and had previously reported doing so in a 2019 assessment. Reference Herstein, Le and McNulty5 All 4 of these facilities reported that the program had decommissioned and/or had discontinued serving in its role as a designated ETC because of discontinuation of HPP Ebola Preparedness & Response Activities funding. Other factors that led to the decision for programs that decommissioned before COVID-19: 3 programs cited diminished perceived threat of EVD or emerging special pathogens, 2 cited lack of administrative support, 2 cited barriers to facility preparedness for proper patient placement, 2 cited staffing difficulties, and 2 cited additional training requirements. For the ETC that decommissioned in June 2020, other deciding factors beyond discontinued funding were reported. Both unit space and consumable supplies and PPE were needed for COVID-19 response, leaving the unit without capabilities to handle an HCID case outside COVID-19. If adequate funding existed to reestablish the ETC program, 25% of the units reported that they would agree to serve in this role again.

Facilities that maintain high-level isolation capabilities

Overall, 33 facilities reported that they maintained high-level isolation capabilities; among them, 28 completed the survey. All 28 responders reported that they plan to maintain those capabilities following the COVID-19 pandemic. To date, these ETCs have incurred a mean of $234,367 (median, $175,000; range, $30,000–600,000) in annual expenses per year, funded by either external or internal sources, to maintain capabilities and capacity. Also, 6 units reported shortfalls in funding, which averaged $163,667 (median, $175,000; range, $30,000–300,000). When asked to list shortfall expenses not covered, 5 ETCs reported full-time equivalent (FTE) funding, 4 reported replacing expired supplies or equipment depreciation, 3 listed overhead costs, and 2 cited major construction.

Several primary funding mechanisms to sustain ETC operations were reported on the survey. Of 27 responding institutions, 23 (85%) reported HPP funding, 18 (67%) reported institutional mechanisms, and 8 (30%) reported state funding (other than through HPP). Funding for ETC capabilities through the HPP Ebola Preparedness and Response Activities lapsed or decreased for 7 (25%) of 28 facilities. Of these 7, 4 (57%) reported that their estimated operational budget for this fiscal year had decreased by a mean of $153,000 (median, $150,000; range, $109,000–200,000). Also, 5 (71%) of these ETCs reported they were uncertain whether the facility would continue to have the financial ability to maintain the unit and capabilities without federal funding. Of the 2 units that reported they would have that ability without federal funding, both estimated that the facility would be able to maintain capabilities for >3 years, and both identified institutional (hospital) funding as other sources of funding or support. Also, 1 institution identified state funding as alternative support.

Role in COVID-19 response

Overall, 29 ETCs (the 28 ETCs that maintained high-level isolation and the ETC that decommissioned mid-2020) completed the section on their role in the COVID-19 response. All but one unit (28 of 29, 97%) reported that existing capabilities (eg, trained staff, infrastructure) before COVID-19 positively affected their hospital’s COVID-19 readiness and response. Respondents detailed the roles the capabilities played in hospital, local, and regional COVID-19 responses (Fig. 1) and unit readiness (Fig. 2). The single unit that reported that those capabilities did not impact COVID-19 readiness and response cited lack of available laboratory testing and cases immediately exceeding capacity as barriers to ETC capabilities that played an early role in the response.

Fig. 1. Role of Ebola treatment center (ETC) high-level isolation capabilities in hospital, local, and regional response to COVID-19, by percentage (N = 27). Note. PUI, patient under investigation; HLIU, high-level isolation; SME, subject-matter expert.

Fig. 2. Pre-existing high-level isolation capabilities that Ebola treatment centers (ETCs) perceived enhanced unit readiness and response to COVID-19, by percentage (N = 27). Note. PPE, personal protective equipment; NETEC, National Emerging Special Pathogens Training and Education Center.

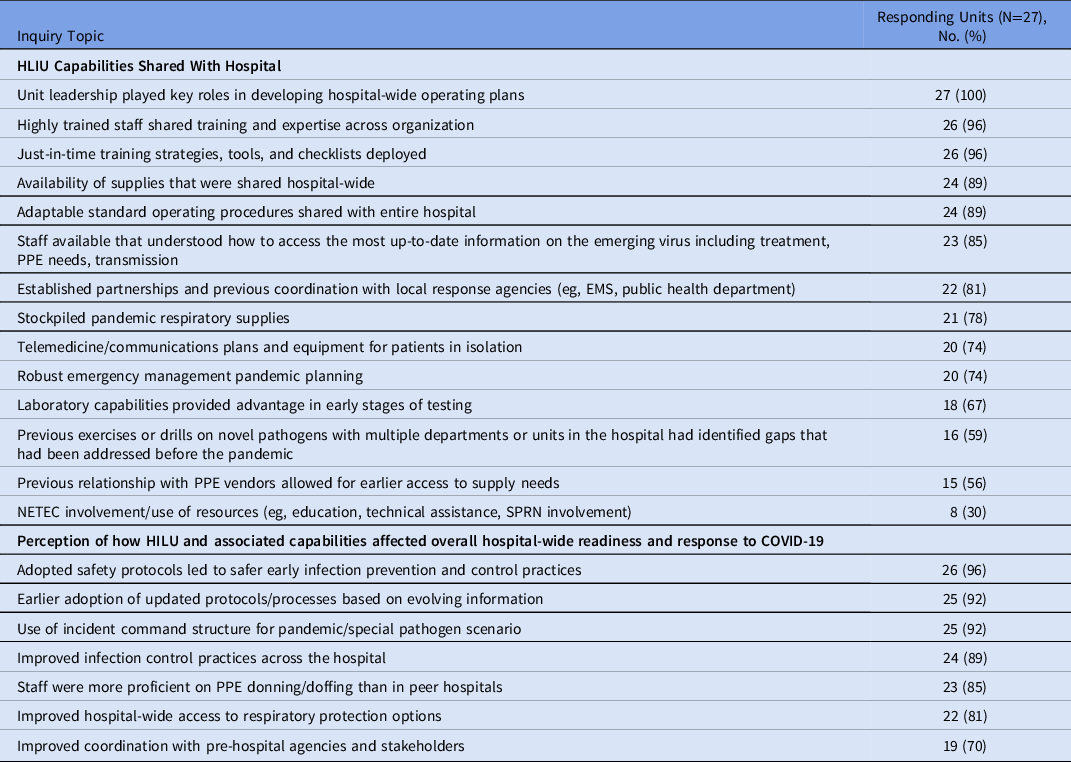

Units reported multiple ways that they shared capabilities with the broader hospital and the perceived outcomes of having those existing capabilities in overall hospital-wide readiness and response to COVID-19 (Table 2). Of 29 ETCs, 22 (76%) reported that they had to rapidly develop or implement capabilities they did not have prior to the COVID pandemic. Also, 15 (52%) reported they had capabilities that they never needed to utilize. Themes from qualitative responses from both questions are detailed in Table 3. Furthermore, 9 (31%) of 29 units reported having capabilities that did not exist prior to the COVID-19 pandemic that they were unable to implement during the pandemic but would work toward for future pandemics. These included flexible and stronger respiratory protection programs, robust records of surge strategies utilized, definitive protocols to address location and level of interaction with parents and affected patients for pediatric care, and improved communication platforms with all caregivers. Table 4 presents ETC lessons learned and innovative practices reported.

Table 2. Reported Ways Ebola Treatment Centers Shared High-Level Isolation Capabilities With the Broader Hospital and Perception of How Those Capabilities Affected Overall Hospital-Wide Readiness and Response to COVID-19 (N=27)

Note. HLIU, high-level isolation unit; EMS, emergency medical services; PPE, personal protective equipment; NETEC, National Emerging Special Pathogens Training and Education Center; SPRN, Special Pathogens Research Network.

Table 3. Reported Pre-existing High-Level Isolation Capabilities Ebola Treatment Centers Used or Did Not Use During the COVID-19 Pandemic Response, as of April 2021 (N = 29)

Note. HLIU, high-level isolation unit; PUI, patient under investigation; PPE, personal protective equipment; PAPR, powered air-purifying respirator.

Table 4. Reported Lessons Learned and Innovative Practices Shared by Responding Ebola Treatment Centers (N = 29)

Note. PPE, personal protective equipment; HLIU, high-level isolation unit; PUI, patient under investigation; SME, subject matter expert; MERS, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome; HCID, high-consequence infectious disease; RESPTC, Regional Ebola and Other Special Pathogens Treatment Center; ETC, Ebola treatment center; EAH, Ebola assessment hospital.

Discussion

As reported by responding ETCs, high-level isolation capabilities and expertise developed following the 2014–2016 EVD epidemic were leveraged to assist hospital-wide readiness for COVID-19 and to support the responses of other local and regional hospitals. When COVID-19 was emerging and information was scarce, ETCs reported caring for the first patients with COVID-19 in their city, state, or region. They also assumed a role in educating and training other staff in their hospital or other area hospitals, donating supplies and equipment stockpiled for HCID response, and adapting and utilizing plans developed for HCIDs for COVID-19 hospital-wide.

Adaptable, highly trained teams and developed training programs and materials were the most cited ETC capabilities that aided in hospital and unit readiness. All responding ETCs reported that unit staff served as trainers or subject-matter experts for the hospital, and half also served as trainers or experts for other local hospitals. Training developed by ETCs was widely shared within the hospital and regionally. Training for healthcare workers providing care for patients with HCIDs is critical: healthcare workers consistently have higher rates of HCID infection than the general public, Reference Selvaraj, Lee, Harrell, Ivanov and Allegranzi11–Reference Xiao, Fang, Chen and He13 a trend also reflected during the COVID-19 pandemic. Reference Nguyen, Drew and Graham14 A lack of infection prevention and control (IPC) training can lead to improper or inconsistent safety practices, such as PPE use, that heighten exposure risks. Reference Wilkason, Lee, Sauer, Nuzzo and McClelland15 Trained staff that have had extensive and recurring (eg, quarterly) training on enhanced IPC practices and rehearsed those skills during exercises and drills are well positioned to serve as trainers and safety observers for other hospital units in surge situations. Despite all ETCs reporting training capabilities enhanced local and, in many cases, regional response to COVID-19, ETCs have previously cited recurring training as the biggest challenge to sustaining operations, apart from financial support, due to its intensive time and resource requirements. Reference Herstein, Le and McNulty16

As reported in this study, the specialized, concentrated expertise that ETCs have developed over the preceding 5 years has been leveraged to support and improve hospital-wide and, in many cases, local and regional readiness and response to the COVID-19 pandemic; however, there is still a national gap in proliferating that expertise to frontline facilities, as was unfortunately demonstrated in the numbers of COVID-19 cases in many skilled nursing facilities. 17 The pandemic has highlighted the need for IPC practices to be ingrained in all healthcare activities and for every healthcare worker to have a baseline IPC excellence. Reference Doll, Hewlett and Bearman18,Reference Popescu19 Moreover, cases and outbreaks of HCIDs in 2021 alone, including 2 different imported monkeypox cases in Texas and Maryland, outbreaks of EVD in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Guinea, and the endemicity of Lassa fever in Nigeria, are important reminders that every hospital must always be ready to identify and isolate potential HCID cases, even as attention and resources remain focused on the COVID-19 pandemic.

In addition to national resources such as the National Emerging Special Pathogens Training and Education Center, ETCs are primed to disseminate their best practices, lessons learned, and subject-matter expertise to other local and regional hospitals in real time; indeed, most ETCs reported doing so during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, improved regional communication was still cited by several ETCs as an area in need of continued improvement. Specifically, ETCs noted a need for better information, sharing best practices, and other resource sharing, as well as greater collaboration across the entire tiered HCID network, which includes regional treatment centers, ETCs, Ebola assessment hospitals, and frontline facilities. Moreover, several units referred to challenges in managing, synthesizing, messaging, and disseminating the sheer volume of information in a meaningful way to their internal teams. This sharing of critical information and messaging strategies can position ETCs within the larger preparedness and response infrastructure as drivers of best practices and future pandemic and HCID policies and actions.

In this study, we identified 3 ETCs that have decommissioned since 2019. Coupled with the 4 facilities that previously reported they are no longer ETCs, Reference Herstein, Le and McNulty5 our assessments have identified that at least 7 former ETCs no longer maintain high-level isolation capabilities, representing 13% of the originally designated units. This finding is concerning, albeit not completely surprising, given the substantial annual costs facilities reported that they incurred: an estimated $234,000 (similar to previous findings of $225,000). These costs did not include the significant investments in establishing the unit, which averaged >$1.4 million per facility. Reference Herstein, Le and McNulty5 Although 75% of the ETCs that maintain capabilities reported HPP funding had not lapsed or decreased, that could well change when temporary COVID-19 supplemental funding is expended. Most ETCs that have experienced a decrease or lapse in HPP funding reported uncertainty regarding whether the facility will have the financial ability to maintain capabilities without federal funding, something other ETCs may soon have to face without mechanisms for continued investments to these units.

Despite the roles ETCs reported filling during the early, evolving COVID-19 response, the uncertainty of future funding to maintain this wider network of ETCs comes at a time when broader public health and biopreparedness funding continue to decline. Repeated patterns of a funding influx for public health and healthcare during a crisis, followed by underfunding during times of calm, threaten to continue despite the significant vulnerabilities the COVID-19 pandemic have exposed. The cost of sustaining these units’ highly trained and adaptable teams, physical infrastructure, resources, and programs (at ∼$234,000/year) is far less than the millions it would cost to reestablish those capabilities. HCID threats will only continue to increase, and the United States will need the capability to respond. By making long-term investments in these ETCs, the capabilities that have already been established can be further expanded and developed. Facilitating more rapid and effective responses to future outbreaks will decrease the funding required for those responses. And, as highlighted during this pandemic and in this study, these investments can be leveraged to enhance broader healthcare system response to non-HCID threats. Reference Cable, Heymann and Uzicanin20 Although originally designed for EVD, ETCs have strengthened capabilities over the years to include respiratory pathogens, and regional treatment centers are expected to care for up to 10 patients with high-consequence respiratory pathogens. 2 However, COVID-19 reinforced the need for ETCs to be more universal in their response capabilities for HCIDs, maintain an HCID-agnostic approach, and plan for flexibility based on mode of transmission. COVID-19 also highlighted the need for ETCs to support surge capabilities during a pandemic response, that is, to create adaptable standard operating procedures for use when physical space is exceeded, to develop local and regional training materials, and to serve in train-the-trainer roles.

This study had several limitations. Responses were self-reported by site representatives. The response rate (66%) was similar to our 2019 assessment of ETCs; however, 5 units only responded to the first question. The survey was disseminated amid many states’ early 2021 COVID-19 surge; as such, many nonresponding facility representatives (often, the unit medical or nursing director) may not have had the bandwidth to complete the survey. We also recognize that over the last several years many facilities have made significant investment into improving hospital preparedness for HCIDs that are not reflected in this survey. Indeed, designated Ebola assessment hospitals have developed many of the same capabilities as ETCs and may have played significant roles in their respective hospitals’ readiness and response to the pandemic which are not represented in this study. Lastly, the study lacked a control group to make direct comparisons of measurable impacts or differential outcomes of these specialized programs compared to non-ETCs. Future studies could determine whether ETCs had better outcomes among patients, higher staff morale, or fewer infections among healthcare staff to provide strong comparative evidence of the value of ETC programs during the pandemic.

In conclusion, in the early weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic, ETCs leveraged their high-level isolation capabilities to support hospital, local, and regional COVID-19 readiness and response. Our findings highlight the roles their programs played, their lessons learned, and the capabilities and expertise shared within their respective hospitals and beyond, as well as the continued challenges they face in sustaining those capabilities for the next HCID threat. Responding operational ETCs have significantly invested in advancing and sustaining capabilities to respond to HCID events over the past 6–7 years. These investments are core components of the US domestic health security infrastructure. The recent presentations of travelers with monkeypox to hospitals in Texas and Maryland, the potential of a patient with Lassa Fever a plane ride away from the United States, in tandem with ongoing cases of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), recent independent outbreaks of EVD, and the COVID-19 pandemic, underscore the value of the ETC network and highlight the importance of funding to support continued operations.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2022.43

Acknowledgments

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.