To prevent transmission of pathogens and healthcare-associated infections, proper infection control is paramount. Hand hygiene has proven very important in the prevention of healthcare-associated infections,Reference Pittet, Hugonnet, Harbarth, Mourouga, Sauvan, Touveneau and Perneger 1 but adherence is low.Reference Tromp, Huis, de Guchteneire, van der Meer, van Achterberg, Hulscher and Bleeker-Rovers 2 , Reference Erasmus, Daha, Brug, Richardus, Behrendt, Vos and van Beeck 3 In addition, proper hand hygiene is hindered by rings, wristwatches, and long sleeves.Reference Pittet, Allegranzi and Boyce 4 , 5 Through jewelry, Reference Fagernes and Lingaas 6 , Reference Jeans, Moore and Nicol 7 artificial nails,Reference Arrowsmith and Taylor 8 and clothingReference Munoz-Price, Arheart and Mills 9 – Reference Mitchell, Spencer and Edmiston 11 healthcare workers (HCWs) can transfer microorganisms to patients, colleagues or themselves. Therefore, a hospital dress code has been defined for HCWs in direct patient care at the VU University Medical Center, a 713-bed tertiary-care hospital in the Netherlands. The dress code entails proper wearing of hospital uniforms and a ‘bare-below-the-elbow’ policy. Although the hospital has set these standards and provides clean uniforms and scrubs every day, compliance with the dress code was poor.

To structurally improve guideline adherence, behavioral change is required. Group norms tend to guide behavior of group members and, therefore, may play an important role in the individual willingness to comply with infection prevention policies.Reference Cialdini and Goldstein 12 , Reference Erasmus 13 To achieve behavioral change, insight is needed into the interaction between individuals, groups, and the working environment and its effect on compliance.

The nominal group technique (NGT) is a decision-making method that involves various panel rounds and combines elements from focus groups and the Delphi method. This structured group process can be used to generate ideas, to reach consensus, and to engage group members in possible ways to solve a problem.Reference Delbecq, VandeVen and Gustafson 14 , Reference Carney, McIntosh and Worth 15 The NGT has proven useful in a range of healthcare settings.Reference Parker 16 Its democratic style, the iterative character, and the avoidance of bias caused by interpretation of the researcher has been shown to promote a high-volume of high quality responses.Reference Asmus 17 Therefore, NGT can help to gain insight in behavioral components and other aspects of noncompliance.

Participatory action research (PAR) is a collective inquiry of researchers and participants aimed at understanding and improving a process.Reference Baum, MacDougall and Smith 18 It is an empowering approach to guideline implementation in healthcare settings.Reference Breimaier, Halfens and Lohrmann 19 Because a PAR approach focuses on adapting interventions to the existing needs of an implementation situation, it might be a suitable approach to enhance compliance.Reference Van Buul, Sikkens, van Agtmael, Kramer, van der Steen and Hertogh 20 We hypothesized that combining PAR with NGT could create behavioral change and improve compliance with our hospital’s dress code. Therefore, we aimed to measure compliance with the dress code, to assess causes of noncompliance, to devise an approach to improve compliance by PAR, and finally, to assess whether this approach was effective in improving compliance.

METHODS

Hospital Dress Code

The hospital dress code is based on guidelines by the Working Group on Infection Prevention (WIP), an independent organization for infection prevention guideline development in the Netherlands. 21 The dress code requires all HCWs (1) to wear hospital uniforms or scrubs when in direct patient care and to change these at least once a day, or sooner if they become visibly contaminated; (2) to adhere to the ‘bare-below-the-elbow’ policy (no long sleeves, no hand or wrist jewelry, and no watches); and (3) to adhere to the guidelines for keeping of hair, beards, and nails (full description in Table 1).

TABLE 1 Hospital Dress Code Based on Dutch National Guidelines

Measurement of Compliance with the Dress Code

Healthcare workers where covertly observed in hospital hallways by an infection control expert and a research nurse, both trained specifically for these observations. HCWs were identified as physicians, nurses or other HCWs by their job-specific uniforms. Job-specific uniforms are provided in accordance with hospital identification card and therefore are a reliable means of identification. Observers noted the type of HCW and scored compliance with every item of the dress code. ‘Compliant with the protocol’ was defined as adherence to all items. At each measurement, 240 HCWs (80 physicians, 80 nurses, and 80 other HCWs) were scored, for a total of 1,920 HCW observations over all 8 time points. Compliance was measured at baseline (T1) and at irregular intervals (T2–T8) thereafter, from March 2014 to June 2016.

Nominal Group Technique

In our hospital, a network of link nurses is operational for improvement of infection control practices. These nurses work on clinical wards or outpatient clinics and act as a link between their own unit and the infection control team. After regular training sessions, link nurses are asked to raise awareness on the discussed topic and to implement accompanying policies by motivating their colleagues to improve clinical practice.

In one of the training sessions, the link nurses were educated in the utility and necessity of the hospital dress code, were trained to observe compliance in their own ward, and were asked to assess causes for noncompliance. To allow the link nurses to fulfill their role, we modified the technique and used 2 consecutive digital sessions to generate an overview of the main causes of noncompliance. In the first session, the link nurses were invited (by e-mail) to discuss the causes of compliance and noncompliance with colleagues on their own ward and to report their findings.

In a second session, the answers were verified; we checked whether all main causes had been identified by presenting the link nurses with an overview of all input. In this session, link nurses were also asked to discuss and prioritize possible solutions with their colleagues. These findings were presented for discussion at meetings of the Nursing Advisory Council and the Medical Staff Advisory Board. With the input of these forms, the overview was finalized, and a consensus was reached regarding the 3 main causes and the priority of interventions.

We combined these outcomes to develop a set of interventions tailored to each group of HCWs or department. Interventions were implemented in collaboration with the link nurses, hospital management, and other relevant stakeholders (PAR). Details of the timeline of the project, and of the final, refined strategy are outlined in Table 2.

TABLE 2 Project Timeline

The Medical Ethics Committee of VUmc assessed the study and concluded that our study deemed exempt from their approval, as it did not include collection of data at the level of patients.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed per type of HCW, per item, and overall for compliance. Results were expressed as proportion of HCWs compliant with hospital dress code. Confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using Wilson’s score. The Taylor series were used to calculate CIs for difference scores. An ordinary least squares regression model was fitted to identify the change in compliance over time using a linear spline with a knot at T2 and an interaction term to assess the effects of the implementation strategy and interaction effects between the groups of HCWs. All analyses were performed with R package version 5.0-0 for regression modeling strategies (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). 22 , Reference Frank E 23

RESULTS

Baseline Compliance (T1)

Compliance results were analyzed per item, overall, and for each group of HCWs separately (Table 3 in supplementary material). Nurses showed higher overall compliance than physicians and other HCWs. In this first measurement, two-thirds of the nurses, less than half of the physicians, and just more than a quarter of other HCWs were compliant with all items of the protocol. Relative to other items, HCWs were least compliant with appropriate wearing of their uniforms. Nurses were more likely to comply with the uniform item than physicians or other HCWs. Physicians also tended to wear wristwatches and long sleeves; therefore, they were less compliant with the ‘bare-below-the-elbow’ policy. Most deviations were observed for the other HCWs; this group wore long sleeves, rings, and wristwatches. Also, many members of this group wore incomplete uniforms (eg, only the jacket instead of the complete uniform).

Main Causes of Noncompliance

The causes of noncompliance were divided into 3 main areas: lack of knowledge, lack of facilities, and negative attitudes.

Lack of knowledge

Nurses described their uniform routines as habitual behavior. Several wards had detailed their own policies and created their own routines without knowledge of their deviation from the hospital policy. Colleagues with administrative positions in the outpatient clinic mentioned that they wore a jacket to be recognizable as a hospital employee. Furthermore, nurses and physicians found the description of some protocol items unclear. Some items were open to interpretation, which led to confusion and discussion. Clarifying the purpose of the policy as an infection prevention measure and providing a clear protocol were identified as possible facilitators for improving compliance.

Lack of facilities

Healthcare workers reported the limited range of uniforms and poor fit as reasons for not wearing the uniform. In particular, nurses described the need for a jacket for warmth during nightshifts. Physicians reported the queue at the distribution point and its location as causing too much delay in obtaining a clean coat and therefore a ‘loss of time.’ The lack of availability of distribution points, uniforms, lockers, and dressing rooms appeared to be the key barrier to compliance; providing extra facilities was identified as a necessity for improving compliance.

Negative attitudes

Physicians mentioned the lack of evidence that a dress code contributes to the prevention of healthcare-associated infections as motivation to deviate from the protocol. Nurses mentioned the influence of negative role models. Addressing these negative role models (ie, heads of medical departments and experienced physicians and nurses) was difficult because of the seniority and status of these role models. Nurses did not address these role models to avoid conflict and confrontation. Promoting a feedback culture, supported by hospital management, and improving awareness among these role models regarding their negative influence on compliance by other HCWs were recommended to improve compliance.

Follow-Up Measurements (T2–T8)

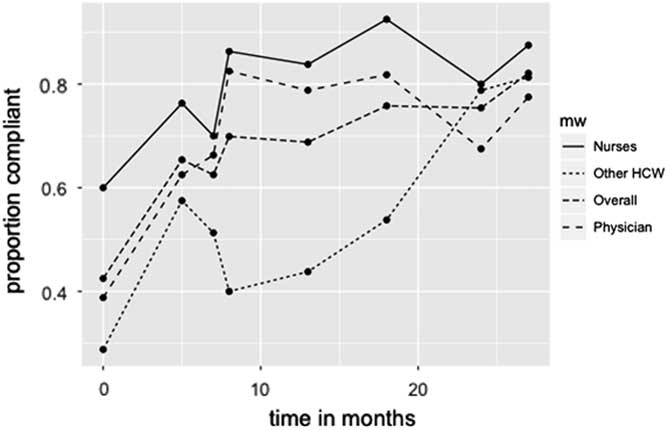

Figure 1 displays the results for overall compliance and compliance per group over the full period of observations (T1–T8). After the first set of interventions aimed at improving knowledge and facilitating employees, the overall compliance with the dress code improved significantly, from 42.5% to 65.4% (β=0.04; P=.001) over a 5-month period. To sustain this improvement, interventions aimed at maintaining focus on the dress code and addressing noncompliant employees were implemented. Thereafter (T3 to T7), an additional significant increase in overall compliance from 65.4% to 82.1% (β=0.0008; P=.01) was achieved. The compliance of physicians increased 38.7% (95% CI, 24.7–52.8) over the whole study period. For nurses and other HCWs, these increases were 27.5% (95% CI, 14.6–40.5) and 52.5% (95% CI, 39.4–65.6), respectively.

FIGURE 1 Proportion of healthcare workers compliant with dress code.

The increase in compliance was sustained throughout the study period for physicians and nurses but not for other HCWs. Between T3 and T7, we focused on strategies to achieve full compliance within this group, which eventually increased compliance to the level of physicians and nurses. Introducing an interaction term for the effect of the intervention strategy in the different groups yielded a nonsignificant effect (P=.06), which indicates the intervention strategy had similar efficacy on all groups.

At the end of the project, compliance had improved significantly for all of the particular items of the protocol (Table 3 in supplementary material). All groups were more compliant with appropriate wearing of their uniform. Physicians also wore wristwatches and long sleeves less often. Other HCWs wore fewer long sleeves, rings, wristwatches, and incomplete uniforms to improve compliance.

DISCUSSION

In this study, hospital-wide compliance with a hospital dress code improved significantly following a tailored intervention strategy. Interventions were based on the main causes for noncompliance, assessed using a nominal group technique (NGT) with stakeholders and a participatory action approach. The results showed an almost 40% absolute increase in compliance. Regular compliance measurements with feedback helped maintain improvement and focus on this hospital standard.

These results strengthen previous findings that, to improve compliance, exploration of barriers and facilitation measures is essential.Reference Carney, McIntosh and Worth 15 Compliance with guideline implementation is considered complex; therefore, assessing the main causes for noncompliance through NGT was the first step in our project instead of the final product. Guideline implementation requires interventions that specifically target identified barriers and take into consideration the department, profession, and setting.Reference Breimaier, Halfens and Lohrmann 19 PAR has been shown to be effective in different groups of HCWs in various fields of health care.Reference Friesen-Storms, Moser, van der Loo, Beurskens and Bours 24 – Reference Collet, Skippen, Mosavianpour, Pitfield, Chakraborty, Hunte and Lindstrom 26 Experiences in infection control show that a PAR approach is a potentially useful method to improve hospital-wide guideline adherence.Reference Battistella, Berto and Bazzo 27 In this collaborative process, working with people in an educative and empowering manner is essential.Reference Van Buul, Sikkens, van Agtmael, Kramer, van der Steen and Hertogh 20 The infection prevention team improved compliance by initiating a discussion regarding causes underlying noncompliance, by exploring possible solutions, and by solving the problem through management support and involvement of all stakeholders. PAR is a cyclical process of research, action, and reflectionReference Kindon, Pain and Kesby 28 ; in contrast to conventional research, we deliberately intervened during the research process.Reference Herr and Anderson 29 PAR is an ongoing process rather than a short-term intervention,Reference Greenwood and Levin 30 and the flexibility of this method offered the possibility to adjust interventions during the project and to take the results from follow-up measurements into account. Physicians and nurses immediately showed a sustained increase in compliance over time after the first set of interventions was applied in our hospital. In the group of other HCWs, the first interventions were not specifically tailored to their departments. Halfway through the project, we started including these HCWs in the interventions, after which their compliance increased to rates comparable to those of nurses and physicians. These findings emphasize the importance of actively involving HCWs in the process and of tailoring interventions to specific groups.Reference Breimaier, Halfens and Lohrmann 19 A punitive approach generally does not lead to a sustainable behavioral changeReference Van der Pligt, Koomen and van Harreveld 31 and was therefore avoided.

As highlighted, items for which noncompliance was highest differed between the different groups of HCW. At the end of the project, these differences remained, but compliance itself had improved. Much of this collective behavior is based on the behavior of role models. Observing the noncompliance of others with a specific norm can influence HCW behavior.Reference Pol and Swankhuizen 32 – Reference Erasmus, Brouwer, van Beeck, Oenema, Daha, Richardus and Vos 34 To see a role model comply and wear the uniform appropriately evokes the so-called cross-norm inhibition effect, which strengthens the perception of the norm and encourages compliance. Nurses in our study described the presence of negative role models as an important cause of noncompliance. Further study could specifically address this aspect.

Our study has some limitations. We performed only 1 standardized baseline measurement. The initial steep increase in compliance could have been incorporated before the implementation of the first set of interventions. However, audits in the previous year showed compliance rates similar to those measured at baseline, which makes an increase in compliance as a result of the interventions likely. Furthermore, we did not measure whether HCWs comply with the daily changing of the uniforms for laundering because data on this part of the protocol were unavailable.

Overall, the democratic, pragmatic approach and its flexibility makes NGT combined with PAR an empowering method that is easy to apply. This behavioral approach appears to be a viable way to improve hospital-wide infection control practices. Therefore, NGT and the resulting tailored interventions were a product of our particular process, and they were specifically applicable in our setting. Therefore, we recommend that this method be applied in other healthcare settings to develop interventions enhancing compliance with protocols and guidelines tailored to the local situation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to express our gratitude to our infection control link nurses network for their contribution to the nominal group technique and to all our role models for fulfilling this role. We acknowledge Liz Armstrong for contributing to the collection of the data and Martijn Stuiver for assistance with the statistical analyses. We also thank Paul van Wijk for contributing to the abstract that preceded this article.

Financial support: No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Potential conflicts of interest: All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2017.233