The Politics of the Past

On December 18, 2018—the forty-year anniversary of Deng Xiaoping’s speech that ushered in an era of Reform and Opening Up—political leaders gathered in the Great Hall of the People to hear Xi Jinping’s retrospective assessment of China’s economic development since 1978. In his exposition, Xi extolled the achievements of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), demarcating a series of reforms that had altered China’s developmental arc—the adoption of the household responsibility system, the creation of township and village enterprises, the repeal of agricultural taxes, the opening of special economic zones, the battle against rural poverty, and, of course, the One Belt, One Road strategy. Conspicuously absent was any mention of the contributions of ordinary citizens to the making of the modern Chinese economy.Footnote 1 The subtext of the omission was clear: The party-state was the motive force of change in the People’s Republic of China.

Historical narrative is not simply a device imposed on the past to make sense of it; rather, it is a “guide to purposeful action directed towards the future.”Footnote 2 Throughout its history, the CCP has mobilized certain narratives of China’s past to “find legitimization … for the domestic and external developments of her most recent present.”Footnote 3 Today, this is most evident in official discourses that describe the historical inevitability of the CCP’s rise and its essential role in guiding China’s socioeconomic transformation.Footnote 4 Chairman Xi has called on Chinese citizens to “learn the histories of the Party and the country, draw experience from the past, have a correct view of major events and important figures in the histories of the Party and the country.”Footnote 5 Through such historical learning, Xi emphasizes, Party members and citizens alike will realize that “without the leadership of the CCP, the country and the Chinese nation could not have made today’s achievements and could not have obtained today’s international status.”Footnote 6

To defend “official history,” the CCP has limited the scale and scope of historical inquiry in recent years by silently re-securitizing formerly accessible archives. In 2012, the No. 2 Historical Archives in Nanjing began refusing requests by foreign scholars to view its holdings, on the grounds that its entire collection was “undergoing digitization”; although the digitization project was slated for completion in 2017, the archives have yet to reopen. China’s Foreign Ministry Archive, which was opened to domestic and foreign scholars in 2004, originally contained more than eighty thousand accessible items in its collection; by 2013, the number of viewable items had been reduced to eight thousand, and in the following year the archives were closed entirely.Footnote 7 In 2017, Tianjin Municipal Archives listed approximately 1.4 million accessible documents in its online index; by 2018, the number inexplicably shrank to fewer than eight hundred thousand documents.Footnote 8

Additional barriers to archival research, in the form of new or previously unenforced rules, have also been erected. In the Beijing and Shanghai Municipal Archives, visiting scholars are now required to affiliate with a Chinese danwei (work unit) and present formal jieshaoxin (letters of introduction) to view the digitized public collections. Other archives are imposing mandatory waiting periods, requiring that foreign scholars arrange visits at least thirty days in advance.Footnote 9 In many archives, researchers are no longer allowed to handle physical documents or to browse through indexes of holdings; rather, they must access them only through digital interfaces.Footnote 10 In a recent survey of more than five hundred international China scholars, 26 percent of respondents reported being denied archival access, while an additional 9 percent had been “invited to tea” by state authorities.Footnote 11 Through such acts, the CCP has articulated its stance that history itself is the sovereign domain of the party-state.

This raises a question of central importance for contemporary business historians: namely, how ought we approach the study of the past in contexts where the production of historical knowledge has been heavily politicized and historical sources are being securitized?

To illustrate how I approached this difficult question in my doctoral dissertation entitled “‘Speculation and Profiteering’: The Entrepreneurial Transformation of Socialist China,” let me begin with a story.Footnote 12

Rescuing History from the Dustbins

One afternoon, while conducting fieldwork in southern China, after an unsuccessful attempt at gaining access to the local archives, I decided to take a stroll through a nearby flea market. There, navigating between rows of stalls, stopping occasionally to rummage through faded socialist memorabilia, I came across a stack of nondescript, brown-jacketed dossiers. I picked up the folder on top of the pile and began flipping through its contents. Inside were dozens of reports on black markets, underground factories, and other “spontaneous capitalist activities” produced during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). Excited about this incredible find, I bought the documents without haggling over the price. When I asked the vendor if he had more, he shared his contact info over WeChat and invited me to visit his home in Anhui. The next week, I went to the address, an apartment located at the edge of a small town. Inside were pillars of documents, stacked from floor to ceiling, with only narrow paths running between them. Save for a small space in the living room that had been carved out for a two-person table, the entire apartment was chock-full of historical material. The majority were documents produced by the lowest levels of government administration that were originally earmarked for destruction, but instead found their way into private circulation.

As I later learned through interviews with document vendors, the diffusion of local archives had occurred through different channels. Some exited the archives during the chaos of the Cultural Revolution, when employees of state agencies began taking home bundles of unimportant documents to burn as heating fuel. Others entered private circulation in the 1980s, when administrative restructuring led to a massive purge of materials that had been accumulated over the previous decades. Because China suffered paper shortages at that time, rather than destroy the documents, archivists were to deliver decommissioned materials to recyclers, who would theoretically reprocess them into paper pulp, but somewhere along this chain of custody, someone instead sold the materials to wholesale merchants. Others documents still were recovered from skips by ragpickers in the 1990s and 2000s who resold them to collectors. And thus, for half a century now, these discarded archival materials have been flowing into and recirculating within private networks.

What do these materials look like? As it happens, they are just as varied as the institutions that produced them. They include the forms, receipts, contracts, and other administrative minutiae produced by grassroots government agencies; the case files of individuals who were prosecuted for economic and political crimes; periodicals compiling the reports and internal correspondences of state institutions; central government directives; heaps of political study materials; and more.

Given that I wanted to explore how the Maoist economy operated in practice, I was immediately drawn to the case files of so-called speculators and profiteers produced by the State Administration for Industry and Commerce (SAIC). These are incredibly rich sources, comprising investigation reports, interrogation transcripts, self-confessions, and other material evidence detailing how individuals tried (and failed) to circumvent the constraints of Maoist economic institutions. Among the cases I salvaged were accounts of arbitragers who smuggled grain and cloth ration certificates across administrative borders and resold them in places where they commanded higher black-market prices; factory technicians employed by state-run enterprises, who, in their off-hours, generated illicit incomes by working as “Sunday engineers” in underground factories; “dark contractors” who recruited teams of unregistered workers from the countryside and illicitly contracted out their labor to formal institutions; “red-hat” enterprises that operated under the aegis of collective institutions, but functioned as private, profit-driven businesses. In contrast to higher-level state documents that describe how the Maoist economy ought to have functioned in highly stylized terms, case files thus offered a radically different vantage from which to understand everyday business practice.

I am not the first scholar to realize the potential of historical documents that were relegated to the dustbins of history by the Chinese state. The pioneering sinologist, Michael Schoenhals, began procuring “rubbish materials” from secondary markets in the 1990s, and he used them to study spy networks and postal inspection systems in Maoist China.Footnote 13 Other sinologists such as Jeremy Brown and Daniel Leese have used recovered materials to explore everyday life under socialism and the tensions between socialist legal principles and practice.Footnote 14 And, until very recently, there was a sizable contingent of social scientists in China who gathered and digitized discarded state documents at scale and used them to build new university-affiliated institutional archives (which subsequently came under pressure to shut down or restrict access to their collections).

While such scholars have been praised for generating novel insights into the minutiae of life in Maoist society, they have also been criticized for “abandoning the commanding heights.” As the political scientist Elizabeth Perry provocatively argues, China historians have consigned themselves to a “janitorial role” wherein they “grub for diversity in the dustbins of grassroots society,” instead of addressing “the key questions that attracted but eluded an earlier generation of social scientists.”Footnote 15 To be sure, this is an ungenerous characterization of an interesting body of research. But it also contains an element of truth. As Jeremy Brown, a prominent “Sinological garbologist,” has argued, “It is near impossible to use a handful of dusty dossiers to build a broad historical argument or to claim that a local example is representative of a wider trend.”Footnote 16

In my work, I have attempted to show that this is not, in fact, the case; it is possible to use discarded materials to, as Perry puts it, ascend the “commanding heights.”

In the following sections I will describe how I attempted to view grassroots sources “from afar” to identify patterns of activity in the Maoist economy. I will then go on to briefly discuss how the insights derived through this approach are supported by other evidence in the historical record.

From the Grass Roots to the Commanding Heights

In the process of rummaging for historical documents, I was fortunate enough to come across relatively complete collections of case files of “speculators and profiteers” who were prosecuted by two local administrations in eastern China. Together, they totaled some 2,690 individual cases. Equally fortunate, in institutional gazetteers published by the municipal branches of the SAIC in both administrations, officials happened to have also reported the total number of cases that were prosecuted within their jurisdictions each year. From this, I was able to gather what percentage of cases were extant, as well as the distribution of extant cases over time. This critical bit of information would enable me to use the cases to generate reasonable estimates of the overall level of informal entrepreneurial activity prosecuted in each administration. To this end, I then turned to coding the data contained within individual cases.

To explain how, let us take, for example, the case of Mr. Ye, a cloth dyer who was prosecuted for moonshining and “labor exploitation” (i.e., running an illicit business that employed unregistered workers). In Mr. Ye’s case file, we are provided a helpful case summary from which we learn that Mr. Ye was seventy-one years of age and came from a “middling-farmer” background. According to the reporting cadres, Ye ran an underground dying business that sold dyed cloth across ten different administrative regions. In the late 1960s, the business generated more than 2,400 RMB in revenues and more than 1,000 RMB in illicit profits. For these economic crimes, Ye was issued a 400 RMB fine. All this information (and much more) can be coded as unique data.

This simplified example belies the difficultly of working with these historical sources. The case files were written by semiliterate cadres who frequently made orthographic errors and homophonic substitutions. Their reporting practices were highly idiosyncratic. Rarely did they use standardized forms. And the materiality of the documents they produced also varied; because of paper shortages, many files were simply written on the back of other government documents. All of this made the process of coding the cases rather arduous and error prone. Reading through nearly 2,700 cases, manually coding their contents into more than 40 categories of data, and checking the resulting data for errors took approximately 2 years.Footnote 17 But what resulted from this endeavor was the largest data set of its kind for Maoist China.

So, what exactly can the data tell us?

First, they reveal something about the spatial scope of informal entrepreneurial activity. Every time a case mentioned that an activity traversed administrative boundaries, I coded the origin and terminus of said activity as nodes and the relationship between the nodes as a unique edge. In Figure 1, I have graphed the resulting distribution of network connections extending from the node of Chun’an (a county-level administration featured in the data set). We find that underground economic activities did not just occur within socialist administrative units, but between them. Indeed, if we examine the core cluster of activity around Chun’an, we find that network connections transitioned smoothly into the adjacent prefectures and provinces. In other words, underground activity does not appear to have been overly constrained by administrative boundaries. Rather, its area seems to have corresponded more to closely to topographical features and the spatial scope of older commercial networks.

Figure 1. Informal networks originating from Chun’an, Zhejiang.

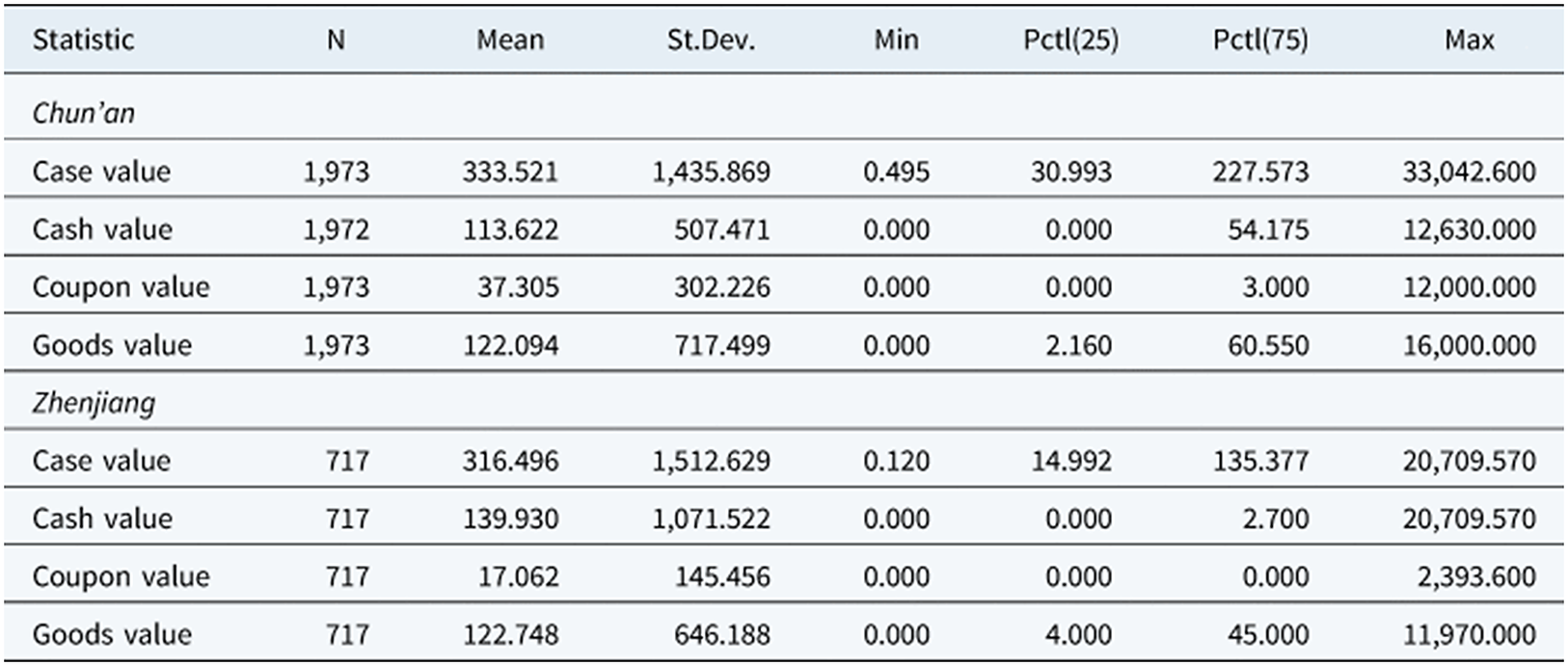

Second, the data reveal something about the scale of informal entrepreneurial activity. Figure 2 presents the summary statistics for the two administrations featured in the data set. Here, we find that the mean value of the activity described in cases was on the order of 300 RMB, and that the average case involved about 150 RMB in combined cash and ration certificates. What is more, the very largest cases involved some tens of thousands of RMB worth of goods, cash, and ration certificates. These are fairly huge numbers. To put the figures into perspective, the mean annual consumption of a rural worker in the 1960s and 1970s was around 100 RMB per year. In other words, the mean case involved quantities of goods whose value represented several years’ of consumption for the mean worker.

Figure 2. Summary statistics.

Third, and perhaps most interestingly, the data suggest that local governments did not faithfully execute central government directives for suppressing illicit economic activity. During the Cultural Revolution, central directives stated that “speculators and profiteers” should be punished with utmost severity and that all goods uncovered in investigations should be seized in full. However, an analysis of prosecution outcomes suggests that individuals who were found guilty of engaging in “speculative and profiteering behaviors” were rarely ever sentenced with extra-monetary forms of punishment; that is, they were not subjected to “reform through labor” in gulags or made the targets of political persecution in public “struggle sessions.” Rather, most individuals were simply fined and released. Moreover, in most cases—especially those that involved large values of cash, goods, and ration certificates—cumulative fines and seizures amounted to only a portion of the total value of described activity. In fact, the size of seizures and fines was inversely correlated with the total value of the activity described. This suggests that local cadres were selective in their enforcement practices, exercising agency over what activities ultimately were suppressed.

The important question then is what could be made of these findings? Were the patterns that emerged from the analysis of the data set indicative of broader trends in the Maoist economy? Or were they merely artifacts of sampling and survivorship bias?

Triangulating Evidence

To begin answering such questions, I then triangulated the case-based data set with evidence from different types of sources, namely, formal archival documents, interviews with retired employees of the SAIC and former entrepreneurs, declassified intelligence reports gathered by Taiwanese and American intelligence agencies, and the internal reports and communications of the SAIC published in institutional periodicals. Similar patterns emerged from the evidence gathered from each type of source. But for the sake of brevity, I will provide just a few quick examples of from the lattermost category.

Much like the case data, the internal reports of SAIC suggested that, over the course of the 1960s and early 1970s, informal entrepreneurial activity grew increasingly pervasive. Throughout the Chinese countryside, local cadres reported a sharp rise in black-market activity. Rural citizens circumvented state procurement institutions to privately exchange a widening array of products and services. Underground factories manufactured goods that were in perennial short supply and sold them at prevailing market (rather than state-fixed) prices. Labor contracting businesses hired workers from production brigades with excess capacity and contracted out their labor to urban enterprises (including collective and state-run enterprises). Logistics businesses smuggled agricultural goods and manufactured products between the cities and countryside. Over time, the proliferation of informal entrepreneurial activity fundamentally reshaped the character of rural markets. As one rural politics department reported:

Our region’s rural markets have been transformed into hotbeds of capitalism and speculative activity. Everyday droves of people participate in market exchange, wasting untold labor power. They freely transact class one and class two goods, such as grains, cotton, and cooking oil. And the quantities being traded are huge! They even trade bicycles, sewing machines, and other manufactured products. It is obvious that these are not proper socialist markets, but capitalist free markets!Footnote 18

The internal reports of the SAIC also confirm that after the outbreak of the Cultural Revolution, as revolutionary struggle disrupted the very institutions that were designed to enforce state control over the economy, local cadres exercised growing autonomy vis-à-vis the center. There are reports of rural production brigades dispatching laborers to engage in illicit commerce and remit profits back to the collective; state-run enterprises operating clandestine production lines and transacting with black-marketeers; state agencies colluding with unregistered enterprises, allowing them to use their official documents and seals to conduct business in exchange for a percentage of their profits. At the same time, the reports suggest, employees of the SAIC and other state institutions had become increasingly complicit in the very activities that they were tasked with suppressing. As members of the Central Committee of the CCP argued:

Many cadres operate with ‘one eye open and one eye shut,’ ignoring the familiar activities of speculators and profiteers. They stroll over here and take a little look over there, and when they see someone selling goods they just let them go. Others have gone so far as to announce at production meetings: ‘As long as you don’t sell opium, anything goes.”Footnote 19

Thus, it was not quite the case, as Frank Dikötter has argued, that grassroots cadres simply “got out of the way” as villagers “surreptitiously reconnected with traditional practices.”Footnote 20 Rather, as these internal reports reveal, local cadres were highly agentic mediators who navigated contradictions between central policies and local practices and ultimately had a say in which activities were prosecuted and which were permitted in practice.

Throughout the dissertation, I attempted to weave together such accounts with quantitative data to explore different facets of the intwined histories of informal entrepreneurship and economic governance in Maoist China. Chapter I laid out the empirical foundations of the following chapters by providing robust quantitative evidence for the persistence and spread of informal entrepreneurial activity. Chapter II focused on the tensions between competitive market and state-fixed prices during and after the CCP’s boldest experiment with socialist economic organization, the Great Leap Forward (1958–1962). Chapter III retraced the history of the subsequent institutional struggle between the SAIC and the so-called spontaneous forces of capitalism throughout the 1960s, highlighting the state’s repeated attempts (and failures) to assert administrative control over the economy. Finally, Chapter IV explored the growth of collusive ties between government officials, state employees, and private market actors in the wake of the early Cultural Revolution. Collectively, these chapters gesture toward a new periodization of economic change in Maoist China, one structured not as a clean-cut series of political campaigns, but as episodes of a messy, uneven transformation that came as much from below as from above.

Like most dissertations, this work was imperfect and incomplete. By focusing on the development of robust quantitative foundations for reassessing the Maoist economy, I necessarily had to reduce emphasis on other, equally valid, modes of historical knowledge production. Present, but admittedly underdeveloped, was the microhistorical analysis of individual cases—precisely the area where other historians drawing on “rubbish materials” have succeeded most. Deeper readings of case files, both “along” and “against the grain,” will be needed to understand the mechanisms by which informal entrepreneurial activity and informal bureaucratic administration operated, interacted, and transformed local economies. Similarly lacking were explorations of regional diversity. We ought to know, for example, how cadres across different administrations responded differently to the rise of informal entrepreneurial activity within their jurisdictions, as well as how these different responses might have contributed to heterogenous developmental outcomes. These are significant shortcomings that I hope to address in my future book.

That being said, the adopted approach did at least open exciting new lines of inquiry and produce a few interesting findings. In my conclusion, I will limit myself to what I think are the three most important.

Conclusions

First, my work pushes back the timeline of China’s transformation by at least two decades, showing how bottom-up entrepreneurial forces were operative throughout the socialist era. Beginning with the earliest enactment of planned production and distribution, there emerged in China informal ecosystems that provided alternative channels for the flow of people, goods, and capital in the planned economy. Despite repeated efforts of the CCP to wage political struggle against private actors and bring them “within the orbit” of socialist institutions, informal entrepreneurship not only persisted, but proliferated. And as it expanded to encompass an ever-growing array of activities, institutions, and actors, it gradually reshaped the workings of the Chinese economy. When the CCP did eventually realize the necessity of reform, many changes they made were simply a formalization of informal entrepreneurial activities that were already pervasive and normalized on the ground. In short, Reform and Opening Up was not the genesis of Chinese entrepreneurship—it was a tipping point.

Second, my work helps deconstruct oversimplifying, antagonistic binaries—for example, state/society, socialist/capitalist, formal/informal—by revealing how state actors and institutions were thoroughly enmeshed in networks of informal entrepreneurial activity. The dissertation reveals that underground factories were manufacturing inputs for sale to state-run enterprises; state-run enterprises were hiring undocumented rural labor and running their own illicit sideline production; unregistered enterprises were operated under the aegis of formal institutions; and local cadres (at least in some places) were actively sheltering this activity from the central government. Thus, the informal was not a realm of activity that existed outside or in the shadows of the formal; rather, informal entrepreneurial activity could be found across all types of institutions and at all levels of the Chinese economy.

Third, and finally, my work demonstrates that Chinese entrepreneurship did not simply survive two decades of socialism, but was remade within it. Recent scholarship has begun to situate China’s postsocialist success within the longer history of Chinese business, using entrepreneurial culture, for example, as an explanation for why regional patterns of business activity have endured over time. While there is much merit to these longue durée analyses, as my work shows, one cannot simply draw a trend line between the pre- and postsocialist periods. During the 1960s and 1970s, new entrepreneurial practices and processes of innovation emerged in response to the particular constraints and opportunities posed by socialist institutions. Moreover, the selection criteria of entrepreneurial success shifted dramatically. The “winners” in the Maoist economy were those who cultivated and deployed personal networks to muster resources, establish business ties, and, ultimately, avoid prosecution in a hostile and ever-shifting sociopolitical context. Some of these are features that we continue to associate with entrepreneurial success in China today. Put most simply, in the history of Chinese entrepreneurship, the Maoist era matters.