Introduction

The transition from the 1950s to the 1960s marked a major turning point in Western fashion, representing the end of what Gilles Lipovetsky designated as the “hundred years’ fashion.”Footnote 1 That is, for a century starting in the 1850s, a fashion system centered on the role of Parisian haute couture as a trendsetting business wherein high fashion influenced mass fashion through a “trickle-down movement,” defined by Georg Simmel.Footnote 2 By the end of World War II, in the last decade of the hundred years’ fashion and following France’s Occupation, haute couture had experienced an intense revival, which historians have defined as a true “golden age.”Footnote 3 This coincided with a state-sponsored and textile-backed aid-to-couture plan from 1952 to 1960, based on the assumption that haute couture would serve as a showcase for French fabrics and thereby develop foreign outlets for the textile industry.Footnote 4 The implementation of this plan by the public authorities at the request of couturiers was a response to the changing fashion context, which was paralleled by that of the couture and textile industry at an international level in the 1950s and 1960s.

These changes are grounded in the democratization of fashion that followed the modernization of the means of production of ready-to-wear garments and the popularization of the dissemination of designers’ lines at department stores.Footnote 5 These developments were part of an international context that itself was going through significant transformation regarding couture and the textile industry. For haute couture, the number of houses had declined from fifty-nine to twenty-five between 1953 and 1973, and their production of clothing models from ninety thousand to thirty thousand. By 1973, to cover the shortfall resulting from the decreased demand for haute couture models, couturiers now integrated licensing agreements into their business model.Footnote 6 The textile industry’s globalization started accelerating in the 1960s, which resulted in a geographic redistribution of production starting in Asia with the advent of Hong Kong as a production center, followed by Taiwan, and South Korea.Footnote 7 As discussed by Dominique Jacomet, global trade in textiles and clothing was respectively $5 billion and $1 billion in 1955 (current dollar) and had increased to $7 billion and $2 billion in 1963, but by 1973, the total had quadrupled to reach $23 billion for textiles and $13 billion for clothing.Footnote 8 This confluence of both international contexts of the couture and textile industry forms the backdrop of the changing fashion system of the 1960s.

This article addresses the following research question: How did the French couture–textile relations evolve within the new fashion system that took shape in the 1960s? In doing so, it makes the case that the diplomatic interest in haute couture as an instrument of France’s commercial diplomacy was the driving force behind its continued importance for the state, rather than its alleged importance for the textile industry. I show this by analyzing archival material that pertains to meetings held between the couturiers, the public authorities, and the various textile branches from 1952 to 1964 concerning the management of the aid-to-couture plan. The minutes of these meetings are complemented by archives from the Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne (the haute couture trade association, hereafter CSCP), the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Finance.

Additionally, this article will also look at key parallels between the Italian and French fashion sectors at the time. This is important because, as Ivan Paris explained, “within the Italian fashion sector during the 1950s, no component was able to maintain a stable horizontally and vertically integrated system,” unlike the French fashion sector.Footnote 9 This means that, during the 1952–1960 aid-to-couture plan, the ties between the textile and fashion industries were still forming in Italy, making it more difficult to represent a unified front capable of proposing events in favor of national rather than regional or sectoral interests. As we will see, this distinction is an important part of French diplomacy’s interest in haute couture.

As such, by cross-referencing the perspectives of the French couturiers, public authorities, and representatives of textile branches, this article seeks to reframe the traditional narrative regarding the importance of haute couture for the French textile industry after the war. Indeed, business historians and researchers working on haute couture have noted the close ties that existed between textile manufacturers and Parisian couturiers. In particular, the seminal work of Didier Grumbach on the history of the French fashion business emphasizes that “since Worth [in the 1850s], haute couture is the spearhead of the textile industry.... A production industry, haute couture leads the textile industry to export markets.”Footnote 10 Grumbach—who from 1961 was at the head of C. Mendès, a clothing company specializing in high-end ready-to-wear—analyzes couture–textile relations from the dressmakers’ perspective. For the 1950s and 1960s, business historians have also conducted studies that reflect the view expressed by Grumbach. Taking a more general view at the soierie manufacturers of the 1950s in his 1960 thesis on Lyon, Michel Laferrère notes that the main reason soierie remained a key partner of high fashion, even if cotton and wool manufacturers had better price, was because of the prestige of its creations and brands.Footnote 11 This finds an echo in the work of historians who study French fabrics manufacturers. In her history of Staron, a French soierie manufacturer, Martine Villelongue notes that although these two decades mark the last years of haute couture’s supremacy, they constituted “un moment magnifique” for soierie.Footnote 12 For his part, Pierre Vernus, working on Bianchini-Férier, another important French soierie manufacturer, recognizes that the most prestigious fabrics manufacturers, such as Ducharne, Pétillaud, and Staron, remained close to the haute couture houses during this period.Footnote 13

By approaching the French couture–textile relations of the 1950s and 1960s mainly through the lens of government-tabled meetings, this article is linked to the broader business and economic history literature on “the glorious thirty,” a term coined by Jean Fourastié to represent the three decades of growth in France between the end of World War II and 1975.Footnote 14 As we will see, even if the 1952–1960 aid-to-couture plan was financed by funds stemming from a tax that originated as a wartime measure of the Vichy regime, its nature was modified in 1948 with the creation of a control committee whose members represented the French public authorities. This was done specifically to help modernize textile production, linking it to the French postwar modernization context at the root of the glorious thirty.Footnote 15 Regarding both government–industry relations and the relative importance of the textile industry, two main characteristics define this period. First, throughout the 1950s and 1960s, even though France moved from the parliamentary Fourth Republic to the Gaullist presidential Fifth Republic, government–industry relations remained the same. As Richard Kuisel explains regarding the Fourth Republic, this relation was grounded on a mixed economic management style that “blended state direction, corporatist bodies, and market forces.”Footnote 16 For his part, Daniel Verdier notes that this management style continued unabated in the 1960s and early 1970s, stating that the decade from 1963 to 1973 “marked the triumph of industrial policy and pressure politics.”Footnote 17 Second, while the growth that France experienced during the glorious thirty is recognized as the “fastest in French economic history,” as French historian Jean-Charles Asselain puts it, this was not the case for the textile industry.Footnote 18 Serge Berstein and Pierre Milza explain that this is a result of emerging new high-tech activities in the 1960s—nuclear, aerospace, electronic—that disturbed the balance in the French industrial context to the detriment of lower-tech industries such as textiles and steel.Footnote 19

In parallel to these works on the glorious thirty, historians have also studied the impact of this period of modernization on the evolution of haute couture’s business model throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Regarding the influence of couture, fashion historian Valerie Steele distinguishes the two roles that couturiers played: as “an advertisement to promote a brand [and as] a laboratory to explore new design ideas.”Footnote 20 This distinction reflects both aspects of the evolution of couture’s business model after World War II, which saw a decline in its couture activities and an increase in the exploitation of brand names through license agreements. This can be illustrated by the conclusions of Tomoko Okawa’s research stating that from the 1960s, “it is the licensed products that assured haute couture’s revenues.”Footnote 21 In short, business historians and fashion historians alike identify two major changes at the root of this upheaval in the 1960s: the advent of ready-to-wear and the new all-important need for brands.Footnote 22

The state of French couture and textiles in the 1950s and 1960s portrays a picture of change in the status of both sectors. On the one hand, the period of growth and modernization of the glorious thirty left the textile industry lagging. On the other hand, the same context inspired major changes to haute couture’s business model, turning it from a craftsperson-based trade to a design-centered brand-advertising business focused on the nascent luxury industry. Interestingly, couture–textile relations are typically presented as remaining positive throughout this period of major change, which contradicts the evolution of the French textile industry after World War II.

This article will address this contradiction in three stages. First, the period of the aid-to-couture plan will be analyzed to understand the evolution of couture–textile relations in the late stage of the hundred years’ fashion, when haute couture still commanded great influence in the world of fashion. Second, the focus will turn to the decoupling of couture and textiles. Third, the French public authorities’ persistent interest in haute couture will be analyzed in light of the decoupling of couture and textiles.

From Aid-to-Couture to Sixties’ Fashion

During the summer of 1951, two major events occurred simultaneously that brought couture and textiles together following years of cool relations after World War II stemming from the fact that the suppliers of tissus spéciaux à la couture (special fabrics)—novel high-fashion fabrics for haute couture and high-end fashion—did not offer haute couture any exclusivity of use. These tissus spéciaux could be used in the couture collections but were also made available to ready-to-wear manufacturers.Footnote 23 In July 1951, Italian high fashion houses (alta moda italiana) presented their collections as a unified group for the second time in Florence, following their first presentation in February, which had foreshadowed their global ambitions.Footnote 24 For the CSCP, this show was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Indeed, Carmel Snow, the influential editor in chief of the American Harper’s Bazaar, sponsored the Italian event, which received boisterous press coverage both in the United States and in France through Paris-Presse. The French couturiers perceived this chain of events with dismay, because they were concerned that it represented the fashion world’s will to move away from France toward Italy.Footnote 25 Adding to that Parisian anxiety in the face of the rise of the Italian high fashion, a global textile crisis was brewing in May 1951. This crisis was a consequence of two changing trends in the global postwar textile industries. First, the modernization of industry worldwide led to an increase in production. Second, this growth in supply was not followed by a corresponding growth in demand, quite the contrary. Indeed, following the postwar exacerbation of demand in textiles—making up for the years of wartime restrictions—demand had now started to stabilize and thus decreased.Footnote 26 For the French textile industry, this meant that by 1952, textile exports had dropped by 46 percent compared with 1951, from 195.4 billion 1952 constant francs to 106.2 billion.Footnote 27

Additionally, the Italian shows that took place in 1951 also marked a key difference between the French and Italian fashion sectors in the 1950s and 1960s. That is, while a single trade association—the CSCP—represented the French couturiers based in Paris, the alta moda italiana was composed of multiple fashion centers: the Ente Italiano Moda of Turin, the Centro Italiano Moda of Milan, and the Comitato della Moda of Rome.Footnote 28 While the shows in Florence, organized by Giovanni Battista Giorgini represented a “turning point in the emancipation of Italy from French inspirations” as Valeria Pinchera and Diego Rinallo put it, they also marked the beginning of what the authors termed “Italy’s fashion civil wars.”Footnote 29 That is, the creation of minor bodies in other Italian cities after 1951, “bringing the total number of Italian organizations promoting fashion to 13,” and the subsequent yearly clashes between the major Italian centers.Footnote 30 These fashion civil wars lasted until the spring of 1965, when the fashion calendar that the Camera Nazionale della Moda—modeled after the CSCP—had been working on since September 1962 “became operational, sanctioning a division of promotional labor built on each city’s vocation.”Footnote 31 This means that, contrary to the case of France, where the centralized action of the couturiers allowed for nation-branding initiatives, it was less the case in Italy, where fashion regionalism remained the norm until the mid-1960s. This is what made the case of France an “ideal, but not necessarily typical situation” according to Pinchera and Rinallo.Footnote 32 As we will see, this feature of French fashion was a key part of its diplomatic appeal.

As such, the fashion show in Florence and textile crisis of the summer of 1951 contributed to a reinforcement of couture–textile relations at a time when public authorities were assessing the relevance of the aid-to-couture plan presented by the CSCP. The reason why couturiers needed financial support after World War II and throughout the 1950s was threefold. First, the postwar inflationary context in France made it necessary to have a lot of capital to start a new business and ensure its day-to-day operations.Footnote 33 In the immediate postwar years, this was compounded by the fact that the traditional affluent private clientele of haute couture had shrunk because of the war.Footnote 34 Second, while the advent of commercial buyers representing mostly American department stores brought an increase in the couture sales of designs and patterns, this was no panacea. As Jacques Heim decried in 1957, a year before being elected president of the CSCP, the risk averseness of these clients meant that 80 to 90 percent of their purchases targeted only the same two or three houses, with Balenciaga and Dior singled out by Heim.Footnote 35 Third, until the turn of the 1970s, Christian Dior was in a unique position, in that his business had been founded in 1946 with capital from the Groupe Boussac, the world’s largest cotton textile group at the time, the other houses having no such affluent backers.Footnote 36

The change in context of the early 1950s had enabled a couture–textile rapprochement that represented the culmination of the French Plan Council’s strategy for high novelty defined in 1948. At the time, it stated that the textile industry should become France’s first export industry, with French special fabrics (haute nouveauté)—and haute couture as its main vector—having the task to lead textiles to foreign markets by mobilizing its international reputation.Footnote 37 In this respect, while the First Modernization Plan covered in part the textile industry, it did so mostly indirectly. This can be explained by Daniel Verdier’s distinction between the two tiers of the postwar French industrial policy separating champions from a second tier “reserved for declining sectors and which was administered by the sector’s trade association.”Footnote 38 In this context, the couture subsidies were administered directly by the trade associations, with the state representatives—a government commissioner for the Ministry of Industry and Commerce and a state controller for the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Finance—serving as mediators between the private trade associations and the public control committee.

Thanks to the couture–textile rapprochement, the CSCP’s proposed aid-to-couture plan of August 1, 1951, was adopted on November 27.Footnote 39 It was officially implemented through the Aid Compact (Convention d’Aide) of July 24, 1952. In its first year, the subsidy was set at 400 million francs, 100 million of which was to be provided by the textile industry.Footnote 40 The remaining 300 million came from the Encouragement Fund for Textile Production (Fonds d’encouragement à la production textile, hereafter Textile Fund), a structure created to manage funds from the Encouragement Tax for Textile Production (Taxe d’encouragement à la production textile, hereafter Textile Tax) created by the act called the “Loi du 15 septembre 1943” to subsidize businesses responsible for supplying or producing textile products in order to avoid price hikes.Footnote 41 A new law implemented on January 6, 1948, instituted a control committee composed of fourteen representatives for all the ministries involved in the Textile Fund and two representatives of agricultural trade associations.Footnote 42 This control committee would be expanded to forty members on December 31, 1953, to better represent the scope of interests in the Textile Fund.Footnote 43 By this point, the original goals of the subsidies had shifted to support research and offset the difference between domestic and global prices.Footnote 44 As such, the wartime-enacted Textile Tax had shifted after the war to comply with the public authorities’ objectives of modernization.

The main goal of the aid-to-couture plan was to help couturiers finance their purchases of French fabrics and to limit to 10 percent the number of garments that could be executed in foreign fabrics.Footnote 45 This plan was dedicated to haute couture creations only and could not be used by couturiers to cover the costs of their “boutique” collections. Indeed, by the start of the 1950s, in France—as in Italy—couturiers had started creating what were termed “boutique” lines: ready-made clothing set between high-end couture garments and mass-produced ready-to-wear apparel.Footnote 46 In the 1950s, the main difference between the French and Italian cases stemmed from the mobilization of such boutique garments by the Italians in the fashion shows in Florence, while the Parisian fashion shows exclusively presented haute couture garments, boutique lines being dissociated from haute couture lines.Footnote 47 This is one of two major differences between the French and Italian experiences. First, as discussed by Gianluigi Di Giangirolamo, the French experience was based on the centralization of interventions around the CSCP, whereas the Italian experience saw local interests prevail to the detriment of a single body.Footnote 48 Second, because “the most successful of the Italian collections were in the boutique category” from the start—not in made-to-measure handmade couture as in France under the aid-to-couture plan—the orientation of the Italian strategy also differed from that of France.Footnote 49

By 1953, the French aid-to-couture plan had already started shifting when the textile industry, still reeling from the global textile crisis of 1952, halted participation in the subsidy scheme, arguing that the Textile Tax was enough of a contribution. This had an immediate impact on the subsidy amount, which diminished to 200 million francs derived exclusively from the Textile Fund.Footnote 50 Following the constitutional change of October 1958, officially inaugurating the Fifth French Republic amid the chaos of the Algerian War, the new structure of the public authorities required an overhaul of the Textile Fund’s control committee; in turn, an inquiry was launched into the usefulness of maintaining the fund.Footnote 51 The government’s inquiry resulted in two reports: the July 20, 1959, Working Group report on the Textile Fund and the Delacour report on the aid-to-couture plan. Both reports criticized the plan’s goal of subsidizing French fabric purchases for haute couture collections by stating that if the textile industry thought haute couture served its interests, it should also shoulder the subsidies. On the other hand, both reports noted that the state should continue to finance promotional activities by haute couture—called propagande—as long as the Textile Fund remained active, given the prestige of these events.Footnote 52

The term used in French at the time, propagande, can be translated as “propaganda” but lacks the (negative) ideological connotation of that English word. This difference is important, because it can be traced to Propaganda, the work of Edward Bernays first published in 1928, before being reissued in 1955 and again in 2005 with an introduction by Mark Crispin Miller, professor of media studies at New York University. As discussed by Miller, Bernays’s attempt at normalizing the word “propaganda” in English failed, his position remaining “eccentric, in the public eye, when this book came out in 1928.”Footnote 53 This is because, as Miller explains, “Propaganda is aimed mainly at Bernays’s potential corporate clientele.”Footnote 54 This is important to note, as the heads of couture houses, not professionals in public relations, expressed the couturiers’ definition of propagande at the time. Moreover, while this text has had an undeniable influence on the field of public relations, it was not translated into French until 2007. Writing in response to the 2007 French release of Propaganda, psychoanalyst Sandrine Aumercier noted the sharp difference that existed between its “legendary fame” in the United States and it being “almost unknown” in France.Footnote 55

For this reason, in the context of haute couture, the couturiers themselves formally defined two major variants: propagande de prestige and propagande commerciale. The former concerned promotional activities intended to advertise the distinctiveness of French fashion to the public. The latter concerned publicity and participation in trade fairs or department store exhibitions.Footnote 56 In this regard, it would be fairer to define haute couture’s propagande as a form of persuasion. Indeed, as David W. Guth notes, the distinction between propaganda and persuasion can be found in the definition proposed by Garth S. Jowett and Victoria O’Donnell in Propaganda and Persuasion (2006). For them, persuasion “is interactive and attempts to satisfy the needs of both persuader and persuadee,” whereas propaganda seeks “to achieve a response that furthers the desired intent of the propagandist.”Footnote 57 Because both couturiers and French authorities sought to support haute couture and the French textile industry by filling a need in the American mass market, the two-way nature of persuasion better reflects the propagande “mandate” of haute couture.

Thus, the foundations of this new propagande mission of haute couture were established on October 24, 1960, when the government dedicated 500,000 new francs exclusively to promotion in foreign markets in addition to the final installment of the aid-to-couture plan.Footnote 58 This Budget spécial (Special Budget), as it was called, illustrated the willingness of the French public authorities to act in accordance with the new fashion context that had dawned at the end of the 1950s, in which pictures or drawings of garments (images de mode) and brands were valued more than fabrics and dresses. This centrality of fashion ideas that appeared in the mid-1950s found a parallel expression in the advent of private styling bureaus, which served the role of trend-forecasting mediators between the consumer market and fashion producers.Footnote 59 While testifying to the increasing importance of fashion ideas and images, the advent of these bureaus was more immediately relevant to the emerging ready-to-wear manufacturers than to Parisian couturiers.Footnote 60 This can be explained by the fact that until the beginning of the 1960s, the average consumer followed “the ukases of the couturiers as best they could,” as explained by Sophie Chapdelaine de Montvalon in her work on French stylists Maïmé Arnodin and Denis Fayolle.Footnote 61 As such, for the subsidized couturiers in the 1950s and early 1960s, the private styling bureaus did not play a prominent role, although they would later come to be important for the couture ready-to-wear (prêt-à-porter des couturiers).Footnote 62

By 1961, the Budget spécial explicitly expressed the views presented in the Working Group and Delacour reports through the actions detailed in the propagande plan of March 1961. These were to target the United States, the United Kingdom, and West Germany to circulate images of haute couture not in fashion magazines but in the general press, prioritizing images of couture rather than garment production with French fabrics.Footnote 63 In the 1960s, this new reality was mainly defined by the dematerialization of fashion through the advent of brands and licenses as all-important tools for the continued existence of haute couture as a creative industry. This shift traces its roots to the mid-1950s with the advent of color photographs in fashion magazines and the role played by newly expanding department stores.

In France, the fourteen pages of color photographs opening the May 1956 issue of Le Jardin des modes marked a key turning point in the presentation of fashion images at a time when Vogue’s French edition still presented drawings.Footnote 64 As for department stores, as explained by Florence Brachet Champsaur in her work on Galeries Lafayette: “Through initiatives such as the 1954 Festival of French Design, Galeries Lafayette aimed to stock mass-market goods and to democratize design for the consumer.”Footnote 65 As such, the dematerialization of fashion was already well underway when television became a new vector in the dissemination of fashion images in the 1960s with the first televised haute couture fashion show taking place in 1962.Footnote 66 This is not to say that television would not play a role in this process of dematerialization, but that the role it played starting in the 1960s was accelerating a process that had already taken root by then.Footnote 67

As Steele notes of the 1950s, “Couture was in the process of changing from a system based on the atelier to one dominated by the global corporate conglomerate.”Footnote 68 During this decade, “French couturier collections were nearly the sole source of inspiration for expensive ready-to-wear, mass-produced clothes, ladies sewing at home, and everything in between.”Footnote 69 By 1967, sales figures of even the most renowned houses had started their irreversible decline.Footnote 70 Thus, the dematerialization of fashion constituted the stage on which the decoupling of couture and textiles took place at the turn of the 1960s.

Decoupling of Haute Couture and the French Textile Industry

To correctly frame the decoupling of the French textile industry and haute couture, it is first necessary to clarify the distinction between the special fabrics suppliers and the other textile branches, as the couture–textile tensions were also felt in the textile industry itself. The special fabrics suppliers were represented by their own trade association, the Chambre Syndicale des Tissus Spéciaux à la Couture (CSTSC). The companies that made up its membership came from a variety of textile branches, including cotton, wool, and soierie. Since the modernization of spinning techniques starting in the interwar period, companies that specialized in soierie fabrics could now also present full collections of novel high-fashion wool fabrics, and vice versa.Footnote 71 By the end of the 1950s, this was compounded by the advent of new synthetic fibers, which presented new opportunities for all the major textile branches. Michel Battiau explains that, by 1959, the Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques (INSEE) had already started to note that the cotton branch was no longer the branch that only worked this fiber, but one that had the suitable tools to work cotton even if it mobilized synthetic fibers, this situation being the same for all other branches.Footnote 72 As discussed by Ivan Paris, these technological innovations had a similar influence in Italy, expanding productivity and, by extension, making it necessary to integrate both textile and apparel production.Footnote 73

Additionally, because a special fabrics supplier was rarely able to produce every type of fabric needed by the couturiers, ad hoc collaborations between a CSTSC member and smaller fabric companies frequently took place.Footnote 74 This can be exemplified in the case of soierie, which was the most important haute couture supplier. In his work on the Lyon soierie, Laferrère explains that soierie included two main “activities”: haute nouveauté (special fabrics suppliers) and nouveauté fantaisie. In short, nouveauté fantaisie’s role was twofold: reproducing haute nouveauté ideas while simplifying them to reduce costs, but also creating original models of fabrics. In both cases, nouveauté fantaisie was useful to the special fabrics suppliers. In the first case, the reproduced models served to meet demands that special fabrics suppliers were unable to meet. In the second case, for a nouveauté fantaisie house to be able to enter the haute nouveauté circuit of soierie, it needed to collaborate with a house that was already a part of it. In turn, this is what Laferrère defines as the originality of Lyon soierie: le négoce (trading). That is, the role of soierie special fabrics suppliers was to collect the purchase orders on a collection of fabric samples presented to customers (e.g., haute couture houses) in order to redistribute them to the manufacturers depending on demand.Footnote 75 This illustration of the intermediary role played by special fabrics suppliers highlights the distance that separated the textile industry as a whole from haute couture, marking a distinction between French haute couture and the boutique ready-to-wear at the root of alta moda italiana collaborating with the textile industry at large.

Nevertheless, another variable specific to the changing context of the French textile industry starting in the mid-1950s played in favor of the couturiers’ arguments that they represented the best vehicle to promote French textile exports. To put this perspective in context, it is important to understand the distinction between silk and soierie as well as the specificity of this textile branch compared with the other major branches of cotton and wool. This is important because, as discussed by Michel Battiau, the advent of synthetic fibers used in the textile industry erupted between 1955 and 1965 in France, being multiplied eightfold.Footnote 76 However, by 1955, soierie already only used 4 percent raw silk, making businesses in this branch far from just covering the natural silk production, contrary to what its name entailed (soie being French for “silk”).Footnote 77

This impressive growth in the development and use of new synthetic fibers such as nylon and polyester resulted in a progressive blurring of the traditional lines between the textile branches, which Battiau defines as an “intertextilisation” of the industry.Footnote 78 That is, more and more, manufacturers of soierie, cotton, and wool could produce similar fabrics by mobilizing comparable amounts of synthetic fibers in their production, while using less of their designated natural fibers. However, as Laferrère argues, this contributed to further specialize soierie toward high-end and high-novelty fabrics compared with cotton and wool manufacturers who mainly mobilized these new fibers to improve their cost prices.Footnote 79

By 1960, soierie manufacturers used 3,985 tons of natural fibers (905 tons of silk, 2,348 tons of cotton, and 732 tons of wool), 26,639 tons of synthetic fibers, and 1,229 tons of diverse fibers and materials.Footnote 80 This eclectic nature of the soierie branch combined with its close bond with haute couture substantiates the case made by the couturiers that haute couture could act as the spearhead of the entire textile industry. Indeed, the fabrics it used were composed of a variety of textiles representing the diversity of the French textile industry’s production.

However, the structural closeness of the special fabrics suppliers—that primarily included soierie manufacturers—and couturiers did not come with exclusive shared interests. On November 8, 1956, the president of the CSTSC, Robert Ducass, laid bare the disconnect between couture and special fabrics suppliers by discussing the total special fabrics purchase figures of subsidized haute couture houses, amounting to roughly 600 million francs by the CSTSC’s account—precisely 548.94 million francs by the Union des industries textiles’ account—which he considered insufficient.Footnote 81 This amount represented the fabrics used in creating the original garments presented in the couture collections as well as the répétitions (replicates) made by the couture houses for their clients. While this number compared advantageously to couture’s total revenues for 1956 of around 5 billion francs—of which 2 billion stemmed from their exports—the crux of the problem rested squarely on the selling of paper patterns to foreign manufacturers, especially American ones.Footnote 82 Indeed, with a ready-to-wear market inspired by couture designs that represented around 1,400 billion francs, it is easy to understand why the CSTSC members demanded couturiers systematically refer buyers of paper patterns to the original special fabrics manufacturers.Footnote 83 In this instance, the couturiers not doing so—because special fabrics suppliers refused to give additional benefits to the couturiers to limit their risks through stock limitations—did nothing to improve the commerce of French textiles.Footnote 84

Between 1960 and 1963, despite the couturiers’ insistence on the alleged importance of couture for the country’s textile industry, representatives of the various textile branches each voiced a different perspective that brought the Parisian couturiers face-to-face with their contradictions. By the end of the aid-to-couture plan in December 1960, the representatives of the textile branches had already made clear that, except for soierie manufacturers, the others were reluctant to commit to any aid whatsoever.Footnote 85 On February 2, 1961, faced with this impasse, Louis Lavenant, the government commissioner in the Aid Commission, presented a thinly veiled ultimatum to the CSCP: if, by the end of April, the textile industry was unable to guarantee any funding for a new aid-to-couture plan, the unspent final subsidy allotment would be dedicated to propagande.Footnote 86 What had appeared to be a temporary couture–textile deadlock following the end of the aid-to-couture plan was to become a fixture of couture–textile relations in the 1960s.

For this reason, on June 9, 1961, the funds remaining from the original aid-to-couture plan were reallocated to the propagande services and activities.Footnote 87 By 1963, French officials grew weary of this stalemate. On June 14, Lavenant explained that he could not fathom why the textile industry, which could afford to help haute couture financially, did not implement a new aid-to-couture plan of their own creation to ensure the long-term survival of couture’s mission of propagande in the service of French textiles. Encouraged by this admonition, Jacques Heim, honorary president of the CSCP, nonetheless recognized that couturiers were facing a new problem. The couturiers now had to convince the textile industry that haute couture’s prestige made investment in this sector more sustainable regarding the influence of its propagande compared with investment in the ready-to-wear industry.Footnote 88

This marks another major difference between the French and Italian cases, because the postwar development of the Italian fashion industry was rooted from the start in ready-to-wear boutique fashions, whereas in France, it was the handmade creations of haute couture houses that were subsidized specifically to support textile exports. Indeed, the parallel “clothing propaganda” (propagande “habillement”) financed by the Textile Fund targeted almost exclusively French consumers of ready-to-wear garments. It was not a subsidy for the expansion of new export opportunities on foreign markets as was the case for the aid-to-couture plan.Footnote 89 In Italy, as examined by Di Giangirolamo, the constitution of a Permanent Advisory Committee in 1963 to discuss financial contributions for promotional events in favor of Italian fashion abroad included representatives of all textile branches, as well as clothing manufacturers beyond only couture and special fabrics representatives.Footnote 90

In France, however, even Heim’s proposition was no longer enough to ensure a rapprochement with the textile industry. On September 25, 1963, as a follow-up to the June 14 meeting at which the textile branches had not been represented, a new meeting took place to allow representatives of each textile branch to voice their opinions. First, François Vigier, executive officer of the trade association of soierie manufacturers (Fédération de la Soierie), reiterated that they were interested in an immediate short-term aid plan that could allow some time to develop a new textile-sponsored plan. Second, Jean David, the director of the trade association of cotton manufacturers (Syndicat Général de l’Industrie Cotonnière Française), noted that they were concerned mainly with household linen as well as menswear and womenswear, making haute couture a somewhat foreign promotional tool in their view. Third, Louis Robichez, the executive officer of the trade association of wool manufacturers (Comité Central de la Laine), explained that they could support a certain form of couture propagande, but that it would not be exclusive to French couture because of the trade association’s ties to the International Wool Secretariat.Footnote 91 Following this barrage of bad news, Heim expressed the CSCP’s frustration, asking the only question that mattered for the couturiers: “Does couture interest the textile industry, yes or no?”Footnote 92

This firm stance adopted by the CSCP and backed by the French public authorities prompted a rapid reaction from the textile industry. On January 14, 1964, couturiers were informed that the trade associations for soierie, cotton, wool, “special fabrics,” and lacework had gathered 60,000 new francs that would constitute a onetime subsidy from the textile industry to haute couture. The nonrenewable nature of this aid led the CSCP to conclude that this meant the end of the propagande role of haute couture.Footnote 93 The declining interest of French textile manufacturers in haute couture was compounded by the changing fashion context of the 1960s, with the decline of haute couture in parallel to the advent of both new designer ready-to-wear and new fashion centers such as London, Rome, Florence, and New York.Footnote 94

In fact, on September 25, 1963, the trade association representatives for the major textile branches had laid bare a disconnect that was rooted in the relative stagnation of the French textile industry’s exports in parallel to the 1952–1960 aid-to-couture plan. Indeed, between 1952 and 1960, the share of textile exports in France’s total exports (outside the franc zone) went from 13 percent to 12.3 percent, going from second to third place in terms of its weight in French trade, behind metallurgy and transport equipment.Footnote 95 As such, even though textile exports grew from 106.2 billion francs in 1952 to 216.2 billion in 1960 (constant francs of 1952) in absolute value, other sectors of the French economy outpaced this growth.Footnote 96 This meant that, contrary to the claims made by the couturiers and special fabrics manufacturers of haute couture being an efficient instrument to promote textile exports, this benefit did not materialize for the majority of textile branches.

Thus, the decoupling of the French textile industry and haute couture was confirmed in 1964 alongside a growing interest among French public authorities in the influence of haute couture on foreign markets. Indeed, the government’s increasing interest in couture was partly responsible for the textile industry’s loss of interest; haute couture was no longer dedicated to the improvement of textile exports, as it had been at the start of the aid-to-couture plan, but had become an instrument of prestige propagande at a national level. In turn, this is connected more generally to France’s postwar commercial diplomacy as defined by the work of Laurence Badel. In her research, Badel explains that the postwar structures of France’s commercial diplomacy that took form in the 1950s through the growing importance of the Directorate of External Economic Relations (Direction des Relations Économiques Extérieures, hereafter DREE) are at the roots of the diplomatie commerciale de prestige (prestigious commercial diplomacy) that took shape during the presidency of Charles de Gaulle (1958–1969).Footnote 97 The peculiarity of this prestigious commercial diplomacy was that it added an additional layer to the traditional diplomatic actions of promoting the trade of French consumer goods and services as well as supporting new export outlets by looking to also disseminate “universalisable values” to reaffirm France’s grandeur.Footnote 98 Badel explains that Renault constitutes a good example of such diplomacy in France in the 1950s and 1960s, “embodying the dynamism of a modern and independent France, which intended to break with the image of a conservatory country for luxury craftsmanship and subject to the United States.”Footnote 99 However, as we will see, the new opportunities generated by the dematerialization of fashion made haute couture an especially interesting prospect for French diplomats in the 1960s. Indeed, by progressively disconnecting ideas from clothing, this phenomenon made it possible to associate the prestige of couture’s brands and fashion images with French consumer goods at large.

Haute Couture and the French Public Authorities

Starting in 1957, the new propagande concept mobilizing haute couture ideas (names, designs, brands) kicked off a series of state-sponsored couture events abroad that reflected the newfound diplomatic interest in fashion’s influence on foreign markets. One key event held in 1957 exemplifies the government’s interest in haute couture, with effects that rippled into the 1960s. From October 14 to 19, Parisian couture houses participated in a series of galas to present haute couture models as part of the French Fortnight (Quinzaine française) organized by the Neiman Marcus department stores from October 14 to 28, 1957. As discussed by Anne E. Peterson in her article on the hundredth anniversary of Neiman Marcus in 2007, this was the first such “Fortnight” staged by Neiman Marcus “to celebrate France and the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the store.”Footnote 100 French models were flown to Dallas to present the couture garments for the occasion (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. “Paris Models at Neiman Marcus.”

Source: Time, October 28, 1957, p. 89. From DeGolyer Library, SMU, Stanley Marcus Papers, a1996.1869.

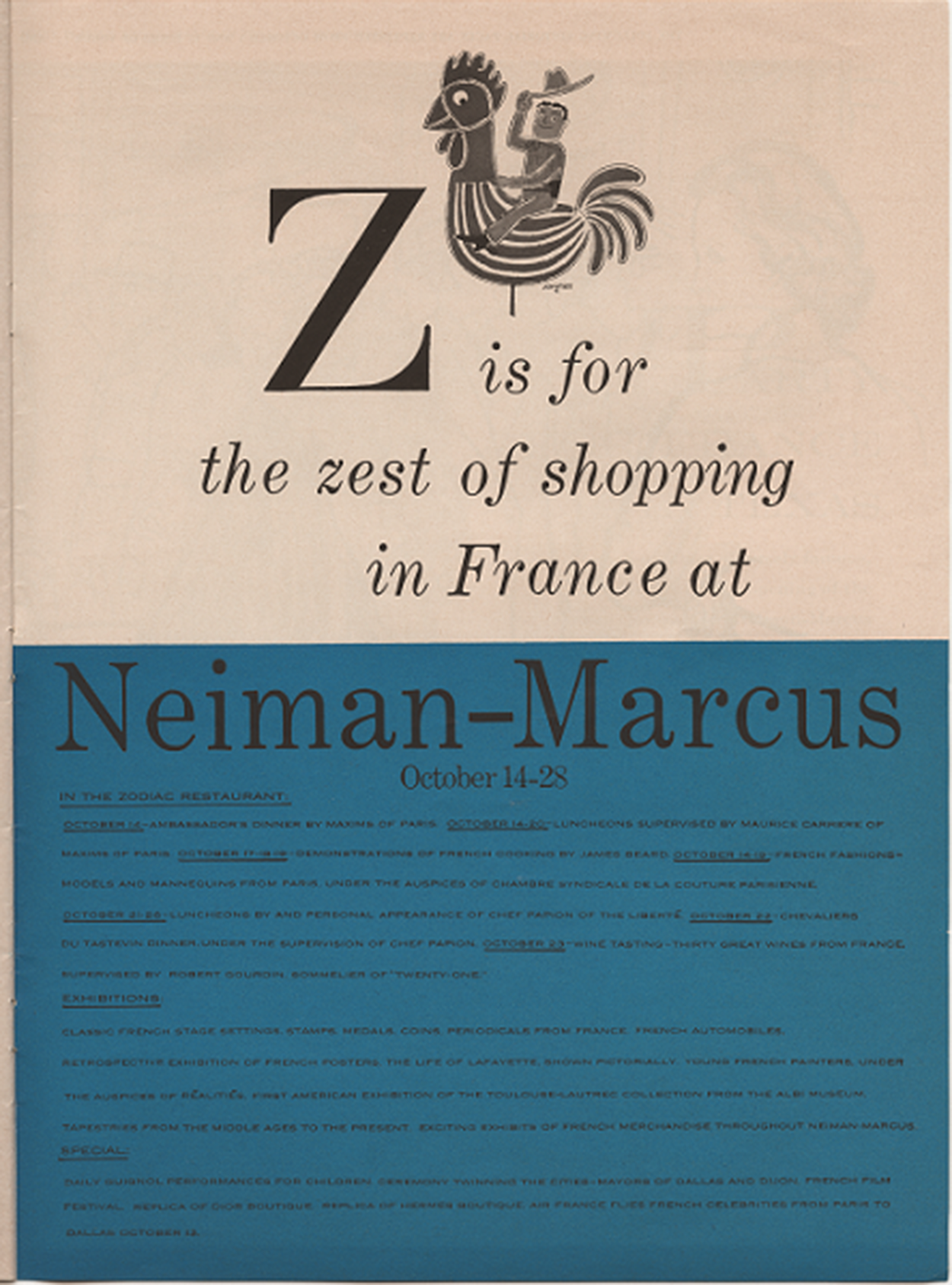

The event was unique in that it was organized by a department store but included the support of French diplomats (either the consul or the commercial counselor) and aimed to promote French products at large and not just haute couture or textiles.Footnote 101 Indeed, many events were organized in the Zodiac Restaurant at Neiman Marcus in Dallas to promote French food and wine, while there were also exhibitions of “French automobiles” and “exciting exhibits of French merchandise throughout Neiman Marcus” (see Figure 2).Footnote 102

Figure 2. The last page of a booklet in which each page represented a specific letter from A to Z dedicated to various French goods.

Source: “Neiman Marcus Brings France to Texas: Everything from A to Z 1957.” From DeGolyer Library, SMU, Stanley Marcus Papers, a1996.1869.

French diplomats perceived this French Fortnight very positively. As reported by the ambassador Hervé Alphand on October 21, 1957: “In terms of French propaganda,... the result has already been achieved.”Footnote 103 An example of this “French propaganda” could be seen in the French atmosphere instilled by the installation of temporary facades as part of the French Fortnight at Neiman Marcus, illustrating the national character of this propagande event (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Temporary facades served to establish a French atmosphere.

Source: “French Fortnight,” DeGolyer Library, SMU, Stanley Marcus Papers, a1996.1869.

Nevertheless, for the couturiers, it was a success in name only. This was because the couturiers were weary of participating in events directly tied to department stores, as it risked diluting the prestige of Parisian couture while mainly benefiting the commercial interest of the store, especially as part of events promoting such a vast expanse of French goods beyond haute couture and “special fabrics.”Footnote 104 Thus, by 1957 the propagande activities of couture did not meet the expectations of either the textile industry or couturiers, but the CSCP agreed to follow through, because the subsidy that reduced creation costs depended on it.

However, on the public authorities’ part, this new approach to propagande through haute couture’s image and ideas was interesting. A note from François Gavoty, the commercial counselor of the French embassy in the United States, illustrates this interest expressed by French officials. On December 6, 1960, he made clear that haute couture was to be one of the highlights of the French Fortnights to ensure wide media coverage of such events.Footnote 105 In short, after the state-sponsored aid-to-couture plan ended in 1960, the government—and especially the DREE—was keen on integrating the propagande role of haute couture into wider French commercial diplomacy. Indeed, as explained by Badel, “In 1945, the network of economic expansion posts abroad was permanently integrated to the DREE.”Footnote 106 Because the French commercial counselor in the United States was also heading the French department of economic expansion in the United States, Gavoty was a key part of the institution of trade attachés that Badel defines as having been “the spearhead of bilateral commercial diplomacy.”Footnote 107 In this regard, the integration of haute couture in commercial events was not trivial, but rather testified to the importance attributed to fashion by French diplomacy. However, the formalization of this diplomatic interest in fashion images happened when the aid-to-couture plan had already been terminated and at a time when French officials still thought the textile industry would replace the aid-to-couture plan with a subsidy scheme of their own. This is an important nuance, as it testifies to the indirect role played by haute couture as part of the French commercial diplomacy of the early 1960s; the DREE never having proposed to instigate a propagande-focused subsidy scheme of its own to compensate for the lack of interest expressed by the representatives of the textile industry.

Between 1960 and 1964, the couturiers’ propagande activities reflected the prestige interest of France’s commercial diplomacy more than the commercial interest of the textile industry. It is important to note that while this shift was occurring in France, the Italian fashion industry was starting to develop its partnership with the textile industry, as had been decided by the newly constituted Permanent Advisory Committee in 1963. As discussed by Di Giangirolamo, this translated in the setting up of the Centre for the Development of Textile, Clothing, and Haute Couture Exports (CITAM) on June 17, 1964, intent on improving collaboration between textile and clothing manufacturers (both alta moda and ready-to-wear) and boosting exports.Footnote 108 This development was consistent with the arguments put forward by the representatives of the French textile branches in September 1963, testifying to the growing importance of ready-to-wear for their outlets. However, by this time in France, the shift in the public authorities’ expectations regarding haute couture’s influence nurtured its relevance in terms of prestige-based diplomatic influence.

Thus, the first series of events that couture planned within the Budget spécial depended on the condition that these events would appear not as prospecting in the U.S. market but as supporting charitable organizations.Footnote 109 From March 1 to 15, 1962, haute couture participated in a series of events in New York (aboard the cruise ship France under the patronage of the wife of the French ambassador), Boston (for the benefit of the Junior League), and Chicago (for cancer research).Footnote 110 On April 19, Jean-Claude Pettit, the French commercial counselor, notified the CSCP that these actions were in line with what the French diplomacy expected in the United States. In a letter to Jean Manusardi, the CSCP executive officer for propagande, Pettit explained that following the event aboard the France, all the French diplomatic representatives—who had earlier met in New York—had reaffirmed their interest in the continuation of couture propagande operations, not only because of their alleged benefit for the French textile industry but also for the positive impact on France’s reputation.Footnote 111

This argument that public authorities presented to the CSCP was the opposite of that of the textile industry. This dissonance between the public authorities’ discourse and the textile industry’s increasing apathy toward haute couture stemmed from the fact that couture propagande activities served the interest of the state more so than that of the textile industry. In September and October 1963, the propagande actions of haute couture sponsored by the Budget spécial returned to their roots of 1957–1960 through participation in French Fortnights held in Chicago and Peoria and a French Week in San Francisco.Footnote 112

Each time, following Gavoty’s note on French Fortnights, haute couture’s propagande objective was to serve as the main highlight of the event and ensure that the presentation kept a national French appeal and avoided becoming solely a publicity stunt for the stores and couture.Footnote 113 As for the public authorities, they conveyed their prestige-based diplomatic objective by asking the CSCP to reserve additional images created of their events to distribute to a wider range of newspapers.Footnote 114 However, following this series of promotional events, the couturiers were to learn on January 14, 1964, that the textile industry would not offer a new textile-sponsored aid-to-couture plan. From this moment, the public authorities’ goal was to stretch the remaining budget as much as possible to ensure the survival of the propagande service by sacrificing direct actions abroad.Footnote 115 As a result, approximately a third of the CSCP’s propagande service operating costs were ensured until August 1967, but the heyday of couture events abroad had passed.Footnote 116

Conclusion

This article highlights the fact that the positive postwar relationship between French haute couture and the country’s textile industry that business historians describe in terms of the golden age of couture was the exception rather than the rule. The couture–textile rapprochement of 1952 was tied directly to the immediate conjuncture of the global textile crisis and the advent of the alta moda italiana. The continuation of the aid-to-couture plan until 1960 had more to do with renewed government interest in the propagande potential of haute couture than with the commercial interests of the textile industry, which started finding new outlets in the burgeoning ready-to-wear industry.

In Italy, this changing context manifested in parallel to the relative concentration of the various parties involved in the fashion industry, having remained decentralized throughout the 1950s. While similar to what the French fashion industry experienced, integration of Italy’s fashion industry came about in the 1960s—most notably through the CITAM—constituted a difference. Indeed, while the collaboration between textiles and fashion in Italy in the mid-1960s sought to boost textile and apparel exports, the expectations of the French public authorities had evolved throughout the 1952–1960 aid-to-couture plan.

In France, this changing context also led to occasional clashes between haute couture and their special fabrics suppliers, who refused to give couturiers the exclusive benefits they thought they were owed because of their alleged importance in the promotion of French fabrics abroad. In turn, the expansion of couture propagande activities toward French products and away from the textile industry led to an increasing disinterest in couture among textile representatives. In parallel, the French public authorities requested more and more of this kind of propagande by the CSCP, seeing foreign media interest in French fashion as a way to promote French business interests beyond the textile industry within the broader framework of France’s postwar commercial diplomacy. This was clearly stated by the French authorities at the conclusion of the aid-to-couture plan in 1960 and presented as a clear way forward through the subsequent Budget spécial allocated to keep the propagande mission afloat until the textile industry presented a plan of its own. However, between 1960 and 1964, when the textile industry made it clear that no such support would be forthcoming, such actions from haute couture remained in line with the public authorities’ expectations of national-level rather than sectoral-level propagande.

By cross-referencing sources from diplomatic, ministerial, business, and multi-stakeholder meetings archives, this article argues that the dematerialization of fashion is the key phenomenon at the heart of both the decoupling of couture and textiles and the newfound government interest in haute couture propagande in the 1960s. This argument contributes to reframing the narrative of postwar French couture–textile relations from a positive one toward a gradual decoupling process accompanied by a couture–diplomacy rapprochement as part of the French commercial diplomacy of the 1960s. Also, because the public authorities played an evolving role between haute couture and the textile industry in the 1950s and 1960s—that of a conductor during the 1952–1960 aid-to-couture plan followed by that of a mediator after 1960—the multi-stakeholder meetings archives are useful for comparing the perspectives of each actor to distinguish between interest and discourse.

There are two important new implications for research on couture and the fashion business. First, by integrating the new fashion context of the 1960s with studies on the 1952–1960 aid-to-couture plan, it was possible to point out that the financing of propagande was not a mishap in the framework of what was at its core an industrial subsidy scheme to support the French textiles trade. In fact, the present article revealed that it was rather the textile part of the aid-to-couture plan that was contextual; the propagande aspect of the aid enduring throughout the 1960s, long after the aid-to-couture plan had ended. Second, the undeniable interest that French diplomatic agents abroad showed in the influence of haute couture and images of its fashions testifies to the importance of considering diplomatic interests in the study of the fashion business, even more so starting in the 1960s, as from then on, dematerialization of fashion becomes the norm.Footnote 117 This is compounded by the fact that haute couture propagande events were mobilized as an indirect but original instrument of France’s postwar commercial diplomacy, highlighting the specific expression of fashion’s diplomatic influence at the confluence of prestige and commerce.Footnote 118 As such, this serves to open a new perspective on the outputs of haute couture by integrating the point of view of consuls and commercial counselors, who observe the influence of fashion in terms of both national business opportunities and media influence.