History and Speculation, Past and Future, are not as separate as they once were in our disciplinary imaginations. Science fiction has emerged as one of many new speculative frequencies in today's scholarly spectrum. Visual representation is an older mode that brings thought and feeling, analytics and prediction together. It pre-dates both historical and fictional narrative forms. Shaped by long histories of artistic and critical conversations, images today are being used in ways that extend and complicate our interdisciplinary scholarly methods. Here, they are put to work in order to pose different questions and suggest alternative analyses of the histories and futures of Asia's changing landscapes.

In dialogue with the speculative conversation inspired by future-oriented fictions and urban-centred theories of China and India, this photo essay is inspired by the photographic oeuvres of two artists – Tong Lam on China and Dipti Desai on India. These juxtaposed images invite us to open up our scholarly analytics to transnational frames, not in a rejection of the national frame altogether, but, rather, via interrogations of the conventions and omissions in local histories and politics. For example, Tong Lam's images of dead spaces in China raise questions about temporality that exceed the standard discussions of lag, catch-up and development. In some of these images, Chinese development seems to have raced far ahead of the West, only to have fallen into some kind of temporal limbo, stuck between a future that never came and a past that responded to mythologies that could not be realized. Dipti Desai's images of dead spaces raise questions about history, memory and nostalgia in the creation of India's Silicon Valley. The spaces of the public sector lie abandoned in the images of the Hindustan Machine Tools (HMT) factory in Bangalore. The city's new steel and glass skyscrapers rise behind the squat concrete buildings of the HMT campus.

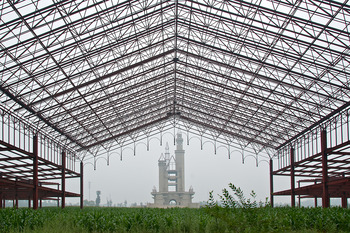

In Lam's and Desai's images, uninhabited buildings or abandoned theme parks, sparkling new cities and infrastructural markers of space exploration and nuclear power silently mark historical eras and political experiments. Local residents continue their everyday lives at scales that appear remote from the grandeur of outer space and atomic energy, but their life-worlds have historically erupted in continual challenges to and disruptions of the nation's techno-scientific dreams.

Social movements in India have been both urban and rural, challenging the social analytics of Euro-American critics who respect the country–city divide in disciplinary forms. The fishworkers' movement off the coast of Kerala voices concerns about workers' rights along with women's labour, environmentalism and transnational trade. The anti-nuclear movement inspires marches in the capital city but also mobilizes villagers in seemingly remote grasslands. But Chinese and Indian citizens are not always resisting modernization and development these days. The world's largest middle classes are enjoying globalized consumption patterns, as we see in Lam's images of urban China. Medieval cities, in Desai's images, unhurriedly incorporate new patterns of trade within very old networks and technologies.

How might we think dialogically about the material geographies of China and India, while not overplaying the familiar comparative analytics of borders and populations, communism and democracy, economic and cultural difference? How might we think in the longue durée about Asian urban and rural change without being overly formalist about theories of development? Rather than using standard historiographic analytics, visual work provokes us to think differently about the histories and futures of these Asian spaces that have rarely been thought together. These images, juxtaposed with textual fragments, offer us possible routes into unfamiliar futures-to-come, recalling but moving speculatively beyond the familiar mid-century originary moments of each nation.Footnote 1

Planning's failures, capital's logics, historical aberrations

When the east is still dark, the west is lit up; when night falls in the south, the day breaks in the north.Footnote 2

At the stroke of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom. A moment comes, which comes but rarely in history, when we step out from the old to the new, when an age ends, and when the soul of a nation, long suppressed, finds utterance.Footnote 3

Figure 1. Urban Slum, Guangzhou, China, 2014 (Tong Lam).

Figure 2. A private development on formerly public land, TATA Aquila Heights/HMT factory, Bangalore, 2013 (Dipti Desai).

Nostalgia, growth, economic miracles

Cities, like dreams, are made of desires and fears, even if the thread of their discourse is secret, their rules are absurd, their perspectives deceitful, and everything conceals something else.Footnote 4

So then, yours is truly a journey through memory! … It was to slough off a burden of nostalgia that you went so far away!Footnote 5

Figure 3. Construction hoarding, Chengdu, China, 2014 (Tong Lam).

Figure 4. Hampi temple complex (ninth to sixteenth centuries), South India, 2013 (Dipti Desai).

Dispossession, dislocation, dereliction

[T]he co-existence of a few railway and steamship lines and motor roads on the one hand and, on the other, the vast number of wheelbarrow paths and trails for pedestrians only …Footnote 6

[T]he very production of the new economy creates its own wasteland – the social space of a dispossessed labour force.Footnote 7

Figure 5. Migrant workers' shack and abandoned theme park, Guangzhou, China, 2015 (Tong Lam).

Figure 6. Nuclear domes, Kudankulam, India, 2012 (Dipti Desai).

Wreckage, debris, speculation

A spectre is haunting devalorized postwar suburban landscapes … the spectre of ‘dead malls'.Footnote 8

Figure 7. Abandoned shopping mall, Dongguan, China, 2013 (Tong Lam).

Figure 8. Abandoned theme park and shopping centre, Dongguan, China, 2012 (Tong Lam).

Figure 9. Unfinished and abandoned amusement park, Beijing, China, 2011 (Tong Lam).

Old resources, new technology, emerging markets

Marx says that revolutions are the locomotive of world history. But perhaps it is quite otherwise. Perhaps revolutions are an attempt by the passengers on this train … to activate the emergency brake.Footnote 9

[T]he pile of debris before him grows toward the sky. What we call progress is this storm.Footnote 10

Figure 10. Artisanal fishermen at the site of decades of protest against foreign fishing vessels, Malabar Coast, India (Dipti Desai).

Figure 11. Site of a temple-town bazaar since the fifteenth century, now razed to develop the Hampi World Heritage Site, Hampi, India, 2013 (Dipti Desai).

Figure 12. Clock and watch repair shops, Bangalore, India, 2014 (Dipti Desai).

Epilogue: histories of the future

The past has left [in history] images comparable to those registered by a light-sensitive plate. The future alone possesses developers strong enough to reveal the image in all its details.Footnote 11

[W]hat kind of a life should a machine age man really lead?Footnote 12

Futures not achieved are only branches of the past: dead branches.Footnote 13

Figure 13. A once-thriving store for the employees of HMT watch factory, Bangalore, India, 2014 (Dipti Desai).

Figure 14. A shepherd's handmade buffalo-leather sandals, gifted at one's wedding and worn for a lifetime. Deccan Plateau, India, 2005 (Dipti Desai).

Figure 15. Outdoor film screening, Chongqing, China, 2014 (Tong Lam).

Figure 16. Discarded old films from the Revolutionary era, Chengdu, China, 2013 (Tong Lam).