Published online by Cambridge University Press: 03 October 2012

2 A few fragments were also given to the British Museum.

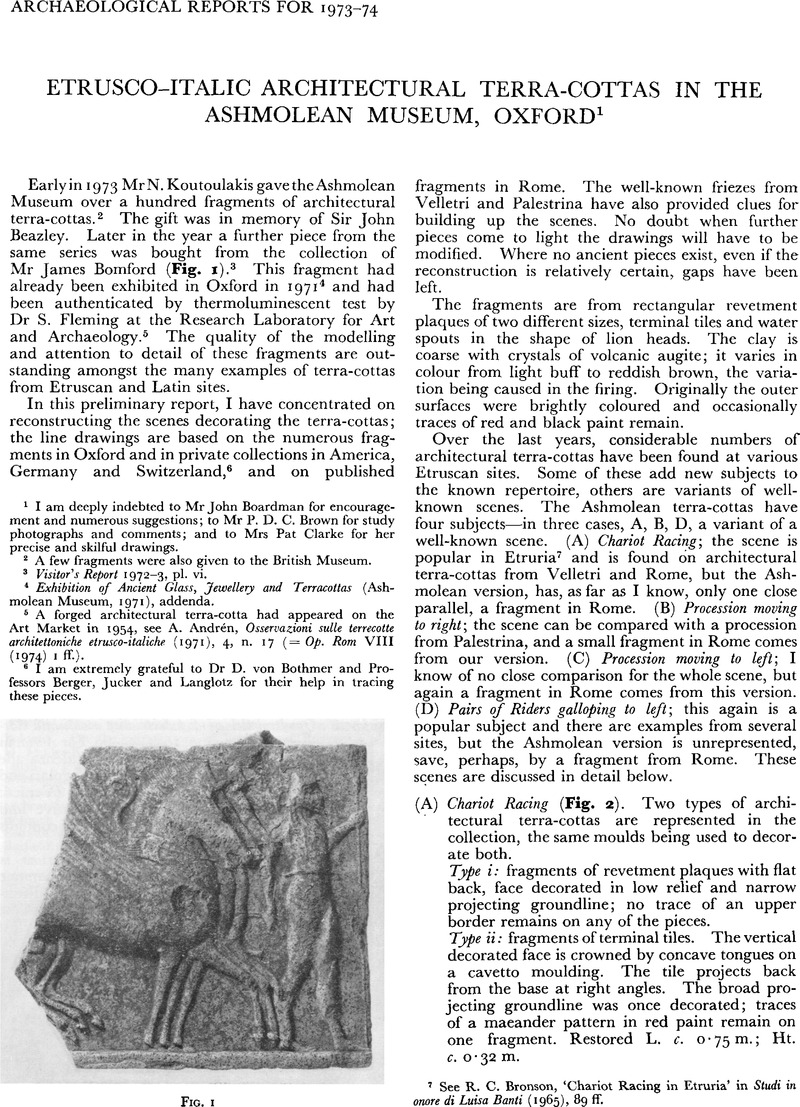

3 Visitor's Report 1972–3, pi. vi.

4 Exhibition of Ancient Glass, Jewellery and Terracottas (Ashmolean Museum, 1971), addenda.

5 A forged architectural terra-cotta had appeared on the Art Market in 1954, see Andrén, A., Osservazioni sulle terrecotte architettoniche etrusco-italiche (1971), 4Google Scholar, n. 17 (= Op. Rom VIII (1974) I ff.).

6 I am extremely grateful to Dr D. von Bothmer and Professors Berger, Jucker and Langlotz for their help in tracing these pieces.

7 See Bronson, R. C., ‘Chariot Racing in Etruria’ in Studi in onore di Luisa Banti (1965), 89 ff.Google Scholar

8 Andrén, A., Architectural Terracottas from Etrusco-Italic Temples (1940), pl. 127, 444.Google Scholar

9 CVA, BM. VII, B.a, pl. 11, 4.

10 Moretti, M., Muovi monumenti della pittura etrusco (1900), 128–9.Google Scholar

11 Andren, A., ‘Osservazioni’, 4Google Scholar , note 17, pl. VII, fig. 20.

12 See Moretti, , op. cit. 108–9Google Scholar for the use of a similar goad in a chariot race decorating La Tomba delle Olimpiadi; Vigneron, P., Le cheval dans l'antiquité Gréco-Romaine (1968) 120Google Scholar, note 3 comments on the use of a long goad for steering the horses.

13 For the use of a triga and possible methods of harnessing see Bronson, R. C., op. cit. 101 ff.Google Scholar; Vigneron, , op. cit. 117 ff.Google Scholar

14 See Cook, R. M., ‘Dogs in Battle’ in Festschrift Andreas Rumpf (1952) 28 ff.Google Scholar: Amyx, D. A., ‘A “Pontie” Amphora in Seattle’ in Hommages à Albert Grenier I (1962), 131Google Scholar note 2 discusses Attic influence on Pontie ware and ‘impressed red-ware’ with dogs and hares.

15 CVA, BM VII, pl. B.a. 11.

16 Åkerström, Å., ‘Untersuchungen über die figürlichen Terrakottafriese aus Etrurien und Latium’ Op. Rom. I (1954), 191 ff.Google Scholar

17 Compare for example, Andren, , Architectural Terracottas, pl. 127, 444Google Scholar; Gjerstad, , Early Rome III (1960)Google Scholar, fig. 54. For some comparisons to the pattern on terra-cottas from Larisa, on Clazomenian sarcorphagi and on vases of various wares see Andrén, , op. cit. cxli.Google Scholar

18 Romanelli, P., Palestrina (1967), pl. XI.Google Scholar

19 Weill, Nicole, ‘Céramique Thasienne à figures noires’ BCH 83 (1959), 437–9CrossRefGoogle Scholar discusses various types of horned helmet.

20 Compare the palmette on the chariot decorating a sima from Palestrina, Romanelli, op. cit. pl. XI, recently discussed by Andrén, , ‘Osservazioni’ 3Google Scholar; a rather similar palmette decorates the chariot on a Pontie vase in Heidelberg, Hampe, R. and Simon, E., Griechische Sagen in der frühen etruskischen Kunst (1964), pl. 23.Google Scholar

21 Gjerstad was unable to find this piece, see Early Rome III, 88, n. i.

22 See Kjellenberg, , Larisa II (1940), 151.Google Scholar

23 Kjellenberg, , op. cit. pl. 9.Google Scholar

24 Compare for example, CVA, BM VII, B.a, p. 11,4.

25 Åkerström, Å., op. cit. 214 ff.Google Scholar

26 Andrén, , Osservazioni, pl. VGoogle Scholar, fig. 13; this fragment was bought on the Art Market.

27 For examples from Cerveteri and Tarquinia see Andrén, , Arch. Terracottas, pls. 4, 22.Google Scholar

28 For a Pontie chariot with triangular forepart covered with an animal skin see the Amphiaraos amphora in Munich, Hampe and Simon, op. cit. pl. 7, 2. The same type of chariot occurs on the bronze strip from the Isis Tomb in the British Museum, see Antike Plastik IV, Abb. 8–9 opposite p. 17. The Olympia fragment is discussed by Yalouris in AJA 75 (1971), 269 ff., pl. 64.

29 John Boardman has kindly drawn my attention to the boar-head chariot on a Pontie vase in Erlangen, illustrated Arch. Anz. XIX ( 1904) 60 f. fig. 1. The boar is very similar to ours.

30 See the Monteleone chariot in New York, Giglioli, , L'Arte Etrusco (1935), pl. 88. 1.Google Scholar

31 Dr Donna Kurtz has drawn my attention to many examples of animal skin caps worn by figures on both Attic Black and Red Figure vases. The closest comparisons to our cap seem to date to the last quarter of the sixth century B.C.; a good detail on an amphora in Brescia by Psiax is illustrated in Arias, , A History of Greek Vase Painting (1962), pl. 67.Google Scholar

32 Åkerström, Å., op. cit. 200 ff.Google Scholar

33 Snodgrass, A. M., ‘The Hoplite Reform and History’ JHS 85 (1965), 116 f.CrossRefGoogle Scholar discusses the introduction of hoplite equipment to Etruria.

34 The right arm is shown in an impossible position in front of the warrior's chest.

35 Compare the clumsier versions of overlapping by the less skilful Velletri artist, Andrén, , Arch. Terracottas, pl. 127Google Scholar, 446. More realistic are the overlapping horses ridden by the pairs of riders, part of a complicated scene, on the sima from Tarquinia; see Colonna, G., in Gli Etruschi; nuove richerche e scoperte (1972), 98Google Scholar, no. 190, pl. xxviiia.

36 See Edrich, K. H.Der ionische Helm (1969)Google Scholar, for this feature; he gives references to its appearance on a variety of wares, note particularly examples on Clazomenian sarcophagi, Pontie vases and on architectural terra-cottas from Pazarli. See also Coek, R. M., CVA BM VIII 15 f.Google Scholar

37 Greenhalgh, P. A. L., Early Greek Warfare (1973), chapter 6.Google Scholar

38 Andrén, , Arch. Terracottas 414Google Scholar, 1: 13, pl. D, 1–2; 333, 1: 10, pl. 105: 375.

39 Andrén, , op. cit. 77Google Scholar, 1, pl. D, 3.

40 Poggio Civitate (Murlo, Siena). The Archaic Sanctuary (Catalogue of the Exhibition, Florence-Siena, 1970), pis. xxii, xxvii.

41 Shoe Meritt, L., ‘Architectural Mouldings from Murlo’, Studi Etruschi 38 (1970), 13 ff.Google ScholarAdditional Note. Apparently identical fragments (just published in Arch. Class. 24 (1972 [1974]) 219 ff.) suggest that all these pieces may come from Pometia, south of Velletri.