During the 1870s, popular scientist Professor Bruce grew accustomed to improvisation as he travelled through the Eastern colonies of Australia. While visiting the timber town of Bulahdelah, on the Central Coast of New South Wales, he lectured on phrenology in his Irish brogue within the best space set aside by town residents for the job. In a hut knocked together from slabs of Eucalyptus, the faint glow of six candles in bottles flickered over the faces of thirty or so locals. The audience crowded onto “three boards deposited on three boxes or casks, in the shape of a triangle” to watch the Professor read heads. “I have seen many entertainments in our bush villages and on stations, but never such a gloomy one,” declared a correspondent. “The more so, as I heard that this hut had been not long ago the depositary of a dead body, awaiting an inquest, and some one called it the ‘dead-house’.”Footnote 1

Throughout Professor Bruce’s tours, the Bulahdelah dead house did not rate as his most dispiriting evening. Nor did his earlier stay in a Victorian town, where an audience participant grabbed Bruce’s beard, causing the lecturer to fall “upon his insulter with real ‘science’, and literally thump … him across the room and back again”.Footnote 2 The nadir perhaps came in 1879, when the Irishman visited the Hunter Valley town of Greta, where prospective audience members leaked away to the competing spectacle of an “alligator” (whether alive or dead the newspaper did not tell).Footnote 3 For the locals, this science that claimed that character and intellect could be determined from the shape of a person’s head – a popular subject often accompanied by public prodding of audience volunteers – could not trump charismatic reptiles. Fortunately, as he hauled himself north towards the sultrier climes of the Colony of Queensland, the Professor also enjoyed warmer receptions, perhaps the result of honing his skills as much as audience inclination.Footnote 4 On the evening of a Boxing Day race meeting in 1883, he held enough public sway to give it to some lads “pretty hot” during public readings.Footnote 5 And by 1900, the “evergreen” lecturer won over his audiences with his “able manner” and illustrations sketched on a blackboard.Footnote 6

Bruce worked at a time when science sprouted tendrils across the settler colonies of Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand. During the second half of the nineteenth century, new universities on either side of the Tasman produced graduates trained in anatomy and medicine and physics, with the first Australian university established in 1850 and the first in Aotearoa New Zealand in 1869.Footnote 7 Articulated whale skeletons haunted both the lawn of the National Museum in inner Melbourne (established in 1854) and the Colonial Museum in Wellington (established in 1865). Savants collected colonial plants and classified them within global taxonomies of flora. Great exhibitions lured crowds to witness the progress and innovation of colonial science. The Great Melbourne Telescope, installed in the city’s observatory in 1869, projected the power of colonial astronomy to the world while gazing out at other planets. Geological surveys traced minerals that lay below the soil. The New Zealand Institute, breathed into life in 1867 by an act of Parliament, by the 1880s bristled with more than 1300 members of the local elite. In short, this bubbling half century saw Antipodean science distilled into institutional structures, sites for processes of increasing scientific professionalisation taking place globally.Footnote 8

But Professor Bruce does not belong to that story.

Rather, he lives for us within a cadre of self-appointed professors who took science to the publics of even the smallest and dustiest new settlements. Such self-taught vernacular scientists made do with belligerence and borrowed titles. They catered to a public taste for emerging knowledges presented with panache, their trails revealing to us the contested nature of science and who could claim its authority.Footnote 9 Among the most prominent and ubiquitous popular scientists, phrenologists offered tangled versions of the cranial system developed by a Viennese physician at the end of the eighteenth century, adapting this contested knowledge into hybrid forms that they then sold to customers as public lectures or private assessments.

Popular phrenology lingers as an ideal artefact through which to study how, during times of transformation for both a region and popular practice, science could perform multiple functions, serving purposes that ranged from financial gain to social advancement to criminal abuses of interpersonal power. In the Tasman World, phrenologists wielded a transnational science in charged negotiations already overlaid by structures of colonisation, class, race and gender. They adapted it to local settings that could become unrecognisable almost from one day to the next, and which were cataclysmic for Indigenous peoples. Their grasp on power was not the expansive sovereignty of the great figures of history. It was limited – just a touch – and a different beast from that solidifying in the universities and museums.

Widely criticised even during the early nineteenth century, phrenology enjoyed success thanks to other virtues. The simplicity of its system rendered it widely understandable and capable of translation into pamphlet and lecture form for the consumption of autodidacts. It provided its practitioners with social authority. It seduced students and practitioners with its promise of teaching them about their innate selves, or about the ever-unknowable other. Its shows created space for play. And its conceptual elasticity meant that aficionados could apply it to individuals or entire populations.

While public head readings promised to reveal the identity of the palpated subject, it was the phrenologists themselves who often concealed layers of artifice. Travelling professors such as Bruce embodied an exquisitely optimistic form of self-crafting characteristic of the colonies, sites of both physical and social mobility that generated long-lasting anxieties about how to trust newcomers. Bruce spent decades touring the East Coast of Australia, and during the mid-1870s sailed across the Tasman Sea to also tickle audiences in Aotearoa New Zealand. But some observers smelled a rat. One Queensland newspaper alluded to the possibility of Bruce’s true self as both a “theatrical amateur” and employee of the local sawmill.Footnote 10 A shapeshifter, Bruce shared the capacious title of ‘phrenologist’ with people who doubled as gold miners, fortune tellers, vagrants, petty criminals, ministers, physicians, actors, elocutionists, barbers and journalists.

Widespread phrenological literacy produced a lexicon of organs and faculties that tripped off colonial tongues as readily as we might today drop phrases from psychoanalysis or yoga into everyday speech. Every part of society dabbled, from the aspiring member of parliament who consulted a phrenologist for a private reading, to a Māori representative at a high-stakes meeting over land with government ministers. Many of these people did not take phrenology seriously, and to properly engage with this popular science, a history of its practitioners and their reception must engage with the joy, earnestness, theatre, wit, ambition, desperation and sometime tragedy of magnificently crumpled lives.Footnote 11

Iterations of this science were at once recognisable but often also only loosely related, and sometimes contradictory. Some practitioners synthesised extensive knowledge of theory with their practices on stage or in private rooms and made phrenology a life’s work. But many in this book plucked just one or two things from practical phrenology’s toolbox, and often for a fleeting moment. The tool of choice could be one of platform oratory – flouncing scripts about natural laws and scientific truth. It might be a professional label – a one-line claim to occupation volleyed by a person dodging jail time for performing abortions or for vagrancy. Or it could be the theatre of scientific subjection alive in the performances of Indigenous people who made their livings from the settler-colonial stage. Yet practitioners, audiences and performers all rummaged in the same box marked “phrenology” for what were often crude but durable implements. What the box lacked in consistency it made up for in availability to the motivations and dreams of people who did not necessarily consider themselves to be acting scientifically.

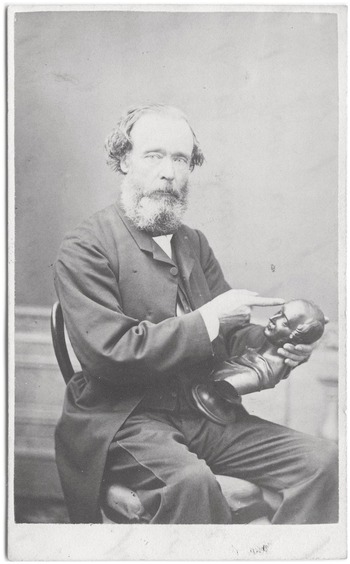

This book therefore makes two interventions: it considers phrenology as an influential practice that played with colonial anxieties about false and shifting identities while enabling the mobilities of its often-shady practitioners. And it follows popular science into the sensory landscape inhabited by its diverse workers (such as Robert White in Figure 0.1), to better understand the interpersonal experiences and conflicts of its protagonists. The phrenological encounter becomes a starting point for accessing the tides of feeling and identity that characterised colonial life. This book considers the past on its own terms. But it also touches upon instabilities surrounding scientific authority that haunt us today.

0.1 Phrenology Heads South

The science that came to be known as phrenology was developed at the end of the eighteenth century in Vienna by physician Franz Josef Gall. He based his theory on a principle that the brain pushed against the skull during development and that the skull therefore took on the shape of the brain, allowing a shortcut to cerebral study through observation and palpation. Gall also declared that different parts of the brain performed specific functions. In the midst of emerging theories about brain and mind, and alongside the development of the disciplines of comparative anatomy and ethnology, his system carved up the brain and skull into twenty-seven specific ‘organs’. The map of the brain developed by Gall created a hierarchy of mental functions. For example, organs related to spiritual connection to God were located at the top of the head, and the base instincts related to violence and sex drive nestled around the base of the skull.Footnote 12 Phrenology took its place alongside sciences of the skull and human type that included comparative anatomy, criminal craniometry, ethnography, nascent forms of psychology and – towards the end of the nineteenth century – population-based analyses of the brain, with the cranial measurements of Nazi doctors during World War II remaining one of the most commonly referenced types of cranial science in popular culture today.

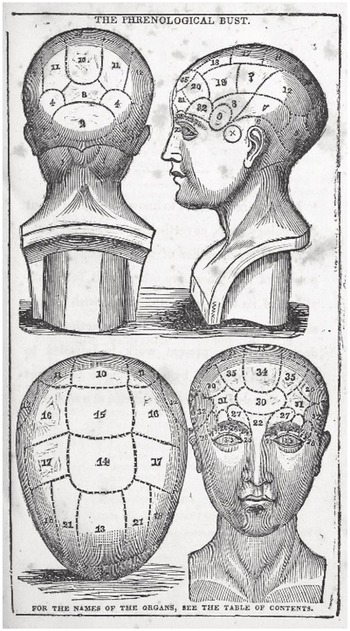

Contested from the outset, phrenology was popularised in the UK and US during the early nineteenth century thanks to Gall’s dissectionist and acolyte Johann Gaspar Spurzheim and the Scottish lawyer George Combe, garnering the interest of members of the middle classes, as well as some members of the élite. Spurzheim and Combe both added more organs to the system (Figure 0.2). They turned it into one of general utility for middle-class life of the period, and buffered its original biological determinism with the principle that people could improve within the reasonable limits of their neural inheritance.Footnote 13 A fortuitous bequest in 1832 helped to turn Combe’s metaphysical treatise – The Constitution of Man Considered in Relation to External Objects – into a book that sold more copies than Darwin’s On the Origin of Species during the nineteenth century.Footnote 14 In America, Spurzheim also won over leading doctors with a tour to New England in 1832, during which he literally lectured himself to death, his body dissected, measured and plucked of brain and locks of hair by friends in a post mortem that transfixed readers across the Atlantic.Footnote 15

Figure 0.2 Combe’s thirty-five organs (with modifications) as they appeared in 1846. Their organisation reflects the system’s symbolic hierarchy. The organs denoting ‘animal’ feelings such as amativeness (sexual instinct) and destructiveness are located at the base of the skull, while veneration (religious worship) perches on top. From: ‘The Phrenological Bust’, in George Combe, Elements of Phrenology (New York: William H Colyer, 1846), iv.

The early decades of phrenological knowledge coincided with the early phases of European colonisation in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand, lands that belonged to a latticework of Indigenous groups for millennia before European explorers sighted their shores through the long reach of a telescope (an event that dates back to the sixteenth-century Dutch exploration of the northern and western Australian coastlines).Footnote 16 Maritime circuits of empire overlapped with Indigenous mobilities. For example, fishhooks found in northern Australia and dated to about 1200 years ago are thought to have come from beyond the continent, possibly from the Torres Strait or Polynesia.Footnote 17 Oral histories and archaeological evidence demonstrate that Indigenous Australians in the northern and north-western reaches of the country traded with Macassan trepang collectors from as early as 1650.Footnote 18

Across the island continent, Indigenous Australians spoke at least 400 languages. Different groups traded objects and knowledge across territorial boundaries and pursued a range of cultural practices and modes of social organisation.Footnote 19 Human habitation in Australia dates back at least 60,000 years, a cavern of time well outside the imagination of the British when they established their penal colony at Sydney Cove on the ancestral country of the Eora people in 1788.Footnote 20 By 1816, when Spurzheim toured phrenology through England, the Colony of New South Wales still clustered around the eastern coastline close to Sydney, although it boasted a pastoral hinterland encroaching on the country of Aboriginal people on the Cumberland Plain . In April of that year, the Governor responded to spates of frontier conflict by sending military expeditions to kill and capture all Aboriginal people.Footnote 21 Meanwhile, Van Diemen’s Land (an island offshore of south-eastern mainland Australia), evolved as a site of European farming, whaling, sealing and secondary punishment, although the traditional owners still maintained classical lifeways on country that would soon change irrevocably. By the time Spurzheim died in Boston in 1832, military endeavours in Van Diemen’s Land to flush Aboriginal people from the bush ended in surviving Tasmanians agreeing to move to Flinders Island on the misinformation that the move was only temporary; instead, three-quarters of the 200 Aboriginal people who ultimately lived on Flinders Island perished there in exile.Footnote 22

Across the Tasman, the ancestors of the Indigenous Māori arrived in South Polynesia – which comprises Aotearoa New Zealand and its surrounding islands – between 1100 ce and 1200 ce – and ever since have migrated internally and engaged in inter-iwi negotiation and conquest.Footnote 23 Around half a millennium of habitation preceded the first European visits – by Dutch explorer Abel Tasman in 1642 and Captain James Cook in 1769. The commencement of commercial sealing around the lower edges of the South Island in the 1790s took place around the same time that Gall, as a young doctor, began developing his theory of individual ‘organs’ in the brain from painstaking empirical observation.Footnote 24 In 1814 (when a European landed gentry was establishing itself in New South Wales), missionaries settled in small pockets in the Bay of Islands, entangling Māori in what Tony Ballantyne terms “webs of interdependence”.Footnote 25 Yet Māori would far outnumber Europeans for decades yet, and developed a rich trade in agricultural produce, exchanging pigs and crops for European goods, and particularly firearms, objects that gave their name to the inter-tribal ‘musket wars’ that peaked during the 1830s.Footnote 26 Despite these pockets of European settlement, the first person to occupy the post of British Resident, James Busby, did not arrive until 1833.Footnote 27

The period of phrenology’s great popularisation in Scotland was met by another frenzy at the Antipodes: the rush for land in Aotearoa New Zealand, with unscrupulous land agents making deals with Māori and selling absurd quantities of land to unwitting investors in Australia and Britain.Footnote 28 By 1839, about 2000 Europeans lived there, and further pressure to establish settlements by groups of entrepreneurs rattled representatives of the British Government, who determined that it should try to establish authority over as much of the archipelago as possible, leading to the Treaty of Waitangi of 1840.Footnote 29 The terms of the treaty were ambiguous and differed between English and Māori versions; historians argue that the signatories could not have predicted the devastating impacts of colonisation that ensued. From this point, the heterogenous world of what James Belich terms “Old New Zealand” co-existed with the arrival of the “instant township”.Footnote 30 With the total population of Aotearoa New Zealand surging by 1881 to more than half a million people overall and by 1901 to more than 800,000 – the recorded Māori population simultaneously declining from 44,097 to 43,112 – the landscape of these islands transformed more quickly and more drastically than in any other European settler-colonial site.Footnote 31

The concept of the ‘Tasman World’, in use by Antipodean historians for some decades, frames a region of interconnection, and also arguably a distinct period.Footnote 32 As Alison Bashford observes, archaeological and other evidence suggests that, before the first Cook voyage, the Tasman Sea functioned as a ‘Tasman Divide’, with no known crossings by either Indigenous Australians or Māori.Footnote 33 The travels of people and products across the Tasman World from the mid-to-late eighteenth century wove an intercultural setting across this sea. During the early nineteenth century, Aotearoa New Zealand, with its resources of timber, flax, whale and seal products, vegetables and maize, became a frontier for the colonies of New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land, with Māori chiefs forging trade ties with their penal neighbours.Footnote 34 By the middle of the century, push and pull factors such as gold rushes, droughts and depressions created major population flows that continue to this day. In the 1880s, for example, up to a fifth of immigrants to Melbourne came from Aotearoa New Zealand, and particularly the South Island, a trend reversed in the 1890s following Victoria’s economic crash.Footnote 35

Many European (or Pākehā) inhabitants thought of themselves as part of ‘Australasia’ – a term dating back to the eighteenth century that looped in any number of land masses of the region, depending on the cartographer – or as Britons eyeing off white imperial expansion into the Pacific. The government of New Zealand attended meetings with other colonies to consider joining first the Federal Council of Australasia and later the Commonwealth. New Zealand’s decision not to federate with its neighbours across the ditch at the turn of the century shaped the emergence of distinct national identities.Footnote 36 While historians debate the exact endpoint to the Tasman World, or if an endpoint even adequately represents continuing shared interests,Footnote 37 the search for distinct national destinies at the turn of the twentieth century marks a close to the colonial phase for this region.

The Tasman World therefore offers a unique proposition for the study of popular science as a tool for advancement. It was a region and period seared by European settler-colonialism at the height of phrenology’s most vigorous public life, a region of immense displacement, mobility and remaking in which a popular practice could shore up momentary power. Recently, historian James Poskett, in his fine work on phrenology, has criticised regional or national frameworks for studying a science that circulated globally.Footnote 38 This was, after all, a transnational practice with both global commonalities and local vernaculars shaped much like books, pamphlets and newsprint within an “imperial commons as a site of deterritorialised sovereignty” (to quote Antoinette Burton and Isabel Hofmeyr).Footnote 39 As Poskett argues, scientific exchange shaped particular geospatial categories.Footnote 40 Yet, studying phrenology within a defined region, with ethnographic attention to pre-colonial land possession and local intercultural practices, offers the opportunity for different but equally compelling interventions into the history of science. This approach provides a textured reading of phrenology’s vernacular possibilities for figures often excluded from historical study. Some of these local iterations may find their twins in other sites around the world, but the sheer variety and vibrancy of phrenology’s practical, everyday life in the Tasman World renders it a compelling setting for the social history of science.

0.2 The Golden Promise of Nineteenth-Century Science

Phrenology’s past popularity – along with its erroneous system and the scientific and social claims to status of its practitioners – has ignited the interest of generations of historians right back to the mid-nineteenth century.Footnote 41 As a lightning rod for criticism, it allows us to chart trajectories of legitimacy during a period when science enjoyed a prominent but changing place in popular culture, and when science’s most vociferous leaders strove to establish their authority as an élite group working from within state-funded institutions.Footnote 42

Characterised by scholars including David De Giustino and Roger Cooter as a reform science that simultaneously shored up power for the ascendant middle classes (by training working classes in a mode of system-thinking congruent with industrialisation), phrenology has been labelled by John Van Wyhe as a tool for blatant personal advancement, a thirst for fame and authority traceable to the continental lecturing tours of its founder, Gall.Footnote 43 Certainly, commercial phrenological empires such as that founded by the Fowler family in the US demonstrate how reformist impulses could dovetail with business savvy to sell mass-produced artefacts such as phrenological busts and publications to a global audience; both political objectives and personal gain could result.Footnote 44 But its reformist reputation belies phrenology’s ultimate ambivalence regarding biological determinism and the degree to which anybody could alter their inherent nature, a contradiction that rendered it the handmaiden of both reformist and conservative positions.Footnote 45

Phrenology arrived in the Antipodes with the early colonial doctors and settlers of south-eastern Australia, a region that was considered a ‘social laboratory’ for the improvement of Europeans through moral and intellectual education and reform.Footnote 46 By the 1850s, members of the colonial intelligentsia who considered the science alongside their medical and administrative appointments were overshadowed by popular lecturers plying a commercial model of the science. Focusing on those figures, this book finds a middle ground between scholarship that takes a class-based approach to phrenology and that which focuses on individual motivations. It agrees with the argument of Fenneke Sysling that personal phrenological readings and charts inducted clients into the zeitgeist of science and selfhood with new insights into their minds and individual selves.Footnote 47 And some of the phrenologists in this book did pursue a reformist agenda while self-consciously grasping the coat-tails of the word ‘scientist’ for the illusion of intellectual authority. But even the most successful among them had to place individual commercial interests before any ideological projects as they pursued a relentless life of touring. While normative phrenological discourses about hygiene and improvement perpetuated by many phrenologists contributed to what Antonio Gramsci called the popular consent necessary for a ruling class to secure its power (a central concept used by Cooter), these messages often sank in the theatrics, chaos and play of phrenological readings, particularly in their seedier iterations.Footnote 48

In Australia during the 1850s, a period of explosive migration stirred by the gold rushes, touring phrenologists trickled through the colonies in ever greater numbers, a growth that continued until the 1880s and 1890s, decades during which more than 120 phrenologists (who appear in records) worked across the Tasman World.Footnote 49 They performed variations that ranged from George Combe’s earnest natural science to something far more feral or hybrid. The many lecturers among them capitalised on mid-nineteenth-century fervour for rational amusement – performances that were seen as educative and improving for the lower classes but which often veered more towards amusement.

Cultures of performance therefore become central to understanding the popularisation of science during the nineteenth century, a force that also gained steam from the emergence of cheap, mass-published works from the 1830s.Footnote 50 At a time when the scientific disciplines as we know them today were unformed or in formation, receptions of science by even the most disenfranchised members of society could be creative and responsive, as demonstrated by the filtering of mid-nineteenth-century debates about evolution into popular shows and folk traditions.Footnote 51 Competing for auditors, performers in London, Melbourne or other cities and towns readily drew on ‘thaumaturgy’, the working of miracles, to tap into an audience capacity for wonder, which also manifested in investigations of metaphysical practices such as spiritualism.Footnote 52

Audiences counted their own observations as among the best ways to verify knowledge.Footnote 53 The pleasure of such theatrical public experiments challenges ideas of the mid-nineteenth century as a period of increasing rationalism and disenchantment, particularly when considering practices such as stage mesmerism, which hinged on exploiting the credulity of people who were deemed more suggestible.Footnote 54 In fact, the contemporary disenchantment narrative often used to frame the Darwinian revolution misses the accommodations that many scientific enthusiasts of the nineteenth century created between science and religion.Footnote 55

Each city or region developed its own scientific culture contingent on its performers, audiences, spaces and competing demands for disposable income.Footnote 56 Many of the popular phrenologists travelling through Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand during the mid-nineteenth century learned their craft in the UK, Europe or America. Yet the geographical contexts of daily life also conditioned audience reception, and the commercial need to meet client whims meant that phrenologists necessarily adapted their shows for local audiences. Thus, in the US, we see the Fowler family declaring in 1849 that the goal of their phrenological journal was to “Perfect our Republic, to reform governmental abuses, and institute a far higher and better state of private society and common usage throughout all our towns and villages”.Footnote 57 In post-revolutionary France, some phrenologists during the 1830s attempted to package the science for the working classes to compensate for the barriers to accessing the centralised educational system of lycées that emerged to cultivate a national intellectual élite.Footnote 58

In Australia, these local elements included a mid-nineteenth-century focus on criminality, tied to the convict origins of the colonies, as well as on the Indigenous body. As a result of the latter, phrenology in the context of Australia has been most studied as a racial science that drove the collecting of Indigenous remains, particularly skulls.Footnote 59 Later in the century, Australia also bestowed on the world the dubious gift of the idiosyncratic bush phrenologist. In Aotearoa New Zealand, practitioners integrated herbal healing practices that appealed to Māori clients.

Frequently de-centring phrenology from the assumptions of a white European worldview, this book draws parallels with the work of historians such as Kapil Raj, who investigates how Indigenous groups in India contributed to the development of disciplines such as cartography and lexicography, adopting and then applying them when defining their places in colonised worlds.Footnote 60 Phrenology, localised in Calcutta, attracted Indian adherents and audiences.Footnote 61 Considering such varied international examples, phrenology becomes an artefact that Indigenous groups weighed up as part of a cross-cultural trade. In the US context, historian Britt Rusert, who applies the idea of ‘fugitive science’ to account for the varied everyday practice of science, complicates ideas about phrenology’s role as a science that reinforced antebellum slavery, revealing how some African Americans drew on this and other popular sciences for purposes of liberation.Footnote 62

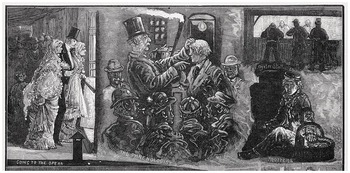

In the Tasman World, the science unfolded at the spatial levels of body, venue and specific locality or Country (the Australian term for land entwined with particular traditional owner groups), and often slid along this scale. Bodies served as mobile sites of knowledge, with individuals empowered or subordinated by the exercise of phrenological touch.Footnote 63 Phrenologists largely focused on individual heads, but some attempted to generalise their studies to thinking about the science at a population level, whether of local community or the budding nation. This echoed the goals of phrenology’s founders for using individual head reading as a means for better understanding types, including national types. The material conditions created by particular venues – whether theatres, throughfares such as Melbourne’s bustling Bourke Street,, or private homes – also framed the phrenological encounter (see Figure 0.3). Beyond that, phrenology tapped into the emotional connections and material experiences that people held in relation to specific Tasman towns, cities and neighbourhoods. The venues of phrenological practice were therefore highly localised and could fluctuate depending on which bodies showed up on any given night.

Figure 0.3 This illustrated feature about Saturday night on Melbourne’s lively Bourke Street depicts a street phrenologist between opera goers (left) and an oyster stall (top right) (Australasian Sketcher, 7 June 1879, 44). The hats worn by the phrenologist’s auditors indicate the varying classes of people consuming phrenology as a popular performance.

0.3 Hunting the Phrenologist

Reclaiming a popular practice from the shadows of nineteenth-century life demands a combination of digital history and classic archival methods. Many of the phrenologists in this book did not leave written archives – diaries, letters and the general detritus of middle and upper-class lives. In fact, some were barely literate, and appear only in registers from magistrates’ courts or notices in police gazettes. The source base for this work therefore spans newspaper articles, court records, papers generated by law-enforcement and municipal agencies, ephemera, advertisements, pamphlets, phrenological charts and material culture in the form of busts and human remains.

Newspapers supply our front-row tickets to the phrenological lecture. Digitised newspaper archives for the region (available through Australia’s Trove and New Zealand’s Papers Past) contain many thousand articles and advertisements related to phrenology. Working through these materials, I generated profiles of about 240 unique practitioners.Footnote 64

We unfortunately cannot know how many practitioners evade the record altogether, whether only a few more than those who appear in this database or many more. Turning to cultural history methods, however, formats such as comic articles, short stories, jokes, songs and even musical theatre reveal how the phrenologist occupied an important role as an archetype of both amusement and horror in the public imagination. Such sources bolster the findings of phrenology as an everyday concept in Tasman life derived from the cohort of phrenologists who rumble within my database.

Fragile biographies provide a corporeal anchor for the influence of ideas transplanted from the other side of the world. Most of these figures hailed from somewhere between the underclass and the lower-middle class, and could at various points be considered subalterns, keeping in mind Clare Anderson’s recent suggestion that subalternity is “a socially contingent process”, and that many figures “hover at the margins of, or fall somewhere between, historians’ binaries of ‘elite’ and ‘marginal’”, a defiance of categories that also often applies to race.Footnote 65

In attempting to reconstruct encounters from scant or blinkered sources in order to understand the motivations and subjectivities of its participants, this book turns to the method of ethnographic history, which studies how small actions fit into larger symbolic meanings and applies reflexivity to the historical task. In line with cultural historian Robert Darnton’s broad definition of symbol as connecting to “any act that conveys a meaning, whether by sound, image, or gesture”, such an approach tacks between historical puzzles in primary sources and surrounding contextual clues.Footnote 66 While this method is here particularly apt for moments of Indigenous and European co-production of performance, I apply it generally to interpreting phrenology in practice. In some cases, this book offers an array of possibilities for participant motivations rather than one definitive answer, but it does so from a rich grounding in context and cross-referencing. Darnton warns that a particular phenomenon or event could “be construed in different ways by different persons, players and spectators alike. But it could not mean anything and everything … rituals contain built-in constraints. They draw on fixed patterns of behaviour and an established range of meanings”.Footnote 67

In cracking the code of phrenological practice, Science and Power in the Nineteenth-Century Tasman World therefore combines the techniques of ethnographic history with methods from social and cultural history to construct what I have elsewhere conceptualised as a ‘history of science from below’.Footnote 68

0.4 Poaching Scientific Power

Questions of power and authority underpin these studies. With its systematisation of the body, phrenology has often been interpreted in the historiography as playing a part in entrenching a complex system of state power, in which the state’s interests in punishment and surveillance became internalised by the individual, as per Michel Foucault.Footnote 69

Yet the many vagrants or marginal figures who fossicked in the phrenological toolbox themselves occupied a vulnerable position in relation to the state, and indeed in relation to the people around them. Popular phrenologists performing on stage became vulnerable to rejection and humiliation by their audiences and clients, their public declarations on scrutinised heads dispersing through the throng like a series of verbal squibs.

Phrenology, despite its claims to establish typologies and order, in fact created sites of struggle. The power that phrenologists wielded during a head reading often manifested in playful, plastic ways. We might think of popular phrenology as one of French philosopher Michel de Certeau’s ‘practices’, if not of everyday life, then certainly of sufficient frequency to have established scripts and tropes recognised by the general population. Its practitioners and audiences, many of whom belonged to lower social orders, became canny users of ‘tactics’, which De Certeau defines as acts that take advantage of fleeting opportunities for temporary gain (as opposed to ‘strategies’, which are longer-term actions performed by those in positions of structural power).Footnote 70 Those who read heads on the road or in bars at best could vie for what De Certeau identifies as the manoeuvres of a poacher or trickster. They would never occupy entrenched positions of power in colonial society, but for a moment could hold authority. For paid performers in phrenomesmeric shows, who often occupied subordinated social positions based on their race or class to that of the ‘professor’, power manifested as the possibility of extracting economic benefit and momentarily subverting the scripted performance.

Other powers brought to the surface in this book derived from the mantle of scientific authority, taking shape during the mid-nineteenth century thanks to the efforts of celebrity scientists and polymaths such as Britain’s John Tyndall and Thomas Huxley. The term ‘scientist’ first appeared in the 1830s in a written work by William Whewell, Master of Trinity College at Cambridge, in which he called for a collective term for those who pursued various strains of natural knowledge. During the second half of the nineteenth century, science came to represent a methodical search for truth, with its social authority increasingly entrenched by the closing decades.Footnote 71 The person claiming scientific authority could wax lyrical on scientific matters far beyond the limits of their own area of study.Footnote 72 The rise of scientific status in the colonies also correlated with the mid-century rise of the professions; older British middle-class values became transposed into a new class status characterised by upward mobility and the slippery idea of merit.Footnote 73 The status snatched by phrenologists from the emergence of scientific and (towards the century’s end) professional authority snared ticket sales and consultation fees.

Negotiations for power took on additional dimensions in settler-colonial settings, where Indigenous groups suffered the onslaughts of any or all of dispossession, European disease, violence and separation from culture. The question of how individuals sought agency in structures of disempowerment permeates literature about Indigenous performers who travelled to Europe to participate in popular ethnological and other displays.Footnote 74 Such tensions can perhaps be best addressed through the proposition of Lynette Russell that Indigenous participants in European economies (such as sealing and whaling) exercised a kind of “attenuated agency”, making the most of a limited range of choices.Footnote 75 “Everyday resistance”, to borrow the words of James C Scott, could manifest as what he terms “weapons of the weak”, including false compliance that masked a hidden script that narrated life “backstage”.Footnote 76

Many of the stories in this book are also deeply grounded in the culture and language of the traditional owners of unique landscapes, reflecting trends towards the local in Indigenous history-making, and a challenge to a monolithic idea of ‘frontier’.Footnote 77 Russell’s work forms part of an historical turn towards examining these questions of structure and agency within the broader context of Indigenous mobilities. As Rachel Standfield cautions, “Indigenous nations have their own polity, territory, unique social organisation and culture”. To study these mobilities and the border crossings that they entail means deflecting focus from European boundaries – drawn first as colonial perimeters and then the nation state.Footnote 78 These specificities are often crucial.

0.5 On the Move

For Europeans – most of whom had not been dispossessed of ancestral land – movement to, and within, the colonies of the Tasman World promised opportunity. The long fingers of British global endeavour helped to build careers for colonial administrators who sought what David Lambert and Alan Lester term “imperial careering” – the second word summoning the double meaning of hurtling, even chaotically, that characterised such sojourns.Footnote 79 While such upward mobility was not available to everyone, particularly during the lows of a depression later in the century, the perception of boundless possibility bewitched those who wrote about the Antipodes.Footnote 80

The line between social mobility and downright imposture blurred in sites such as Australia and the Cape Colony of the early nineteenth century, argues historian of empire Kirsten McKenzie.Footnote 81 She notes that, globally, the Australian colonies became seen as a site of escape and reinvention, although the luck of even the most daring impostors often floundered as global information networks caught up with their exploits.Footnote 82 In response to anxieties about reinvention, the middle classes by the mid-nineteenth century had developed closely policed codes of manners and gentility to stand in for identities defined by class and property.Footnote 83 In private, colonists closely scrutinised each other for traces of shady pasts, while in public such questions became highly distasteful.Footnote 84 As Tom Griffiths observes, “there were enough family trees with missing branches, enough altered dates of birth and sufficient coyness about origins, for observers to realise that there was something there to be forgotten”.Footnote 85 Residents of Aotearoa New Zealand muttered about Australian convicts. Australians muttered about French convicts escaping from New Caledonia, a panic linked to a process of public disavowal of Australia’s convict past.Footnote 86

Into this patchwork social fabric poured the gold seekers who began scratching their way across a sequence of Tasman colonies from 1851, when the discovery of gold was announced in Victoria. Between 1851 and 1861, Victoria’s population grew five-fold to more than half a million people, with Australia’s overall population reaching more than a million.Footnote 87 Relatively new towns grew or contracted as gold ran out, some becoming crucial regional centres.Footnote 88 Sprouting overnight in ravaged landscapes, they rippled with distrust.Footnote 89

Gold rushes across the Tasman began at the South Island settlement of Tuapeka in Otago in 1861 and spread from there, linking Victoria to Otago and Canterbury in a transient gold-rush population. The human networks of southern gold regions connected to larger international networks of trade, configurations likened to those of the spice or slavery trades.Footnote 90 In the later decades of the century, gold booms in Queensland (1870s–1880s) and Western Australia (1890s) drew prospectors north and west.Footnote 91 These diverse communities housed figures from a range of cultures (most notably Chinese prospectors), with some miners travelling to the Tasman World from the California gold rushes.Footnote 92

Anxieties about convicts and ruffians also coincided with a time when increasing urbanisation brought greater anonymity.Footnote 93 Despite the central role of the bush myth in Australian culture, Australia has long been highly urbanised, its city dwellers including the writers who crafted a romantic and eucalypt-drenched tradition of radical nationalism by the end of the nineteenth century.Footnote 94

Travelling for commercial ends between the late 1840s and early twentieth century, popular phrenologists therefore entered milieux infused with a combination of concerns about neighbours: an expectation that people would move in and then on, a general malaise about knowability in modern life, and a suspicion that people hid unsavoury, criminal pasts.

0.6 Anxious Play

The act of publicly reading heads and declaring them to a gathered audience of neighbours ostensibly promised insight in these charged environments. Yet the ritual of reading heads made sport of this anxiety, even as it promised to reveal the bare biological truth of a person’s identity. And the questions of who was dressing up and how they did so took on fantastical permutations. As commonly as popular phrenologists puffed up their credentials to become authoritative scientists, middle-class customers roughed up their appearance to turn up to consultations as lecherous vagabonds, participating in an indulgent form of bourgeois inversion in which “the dominant squanders its symbolic capital” in order to access forbidden desires.Footnote 95

Popular phrenologists understood that disorder and doubt could make a show, and sometimes actively scripted disruption to heighten the sense of drama. This potential for cranial mischief became encoded in the popular culture of the late nineteenth century. The joker, writes anthropologist Mary Douglas, holds a privileged position in which “disruptive comments” express the consensus of the social group itself to “lighten … for everyone the oppressiveness of social reality, demonstrate … its arbitrariness by making light of formality in general, and expresses the creative possibilities of the situation”.Footnote 96 Here, the joker played with ever-present concerns about identity. Welcoming a phrenologist into their community, town residents therefore invited disruption into the social fabric, a form of play that also ostensibly promised a restoration of rightful order based on inherent biology.

The drunkard and the mayor both faced ridicule and unmasking on stage when bodies coded with different classes, genders and races jumbled together, offering the frisson inherent to the mixing of lower and higher orders.Footnote 97 Yet, did this moment of ‘carnival’, as theorised by Mikhail Bakhtin, serve as a pressure valve of sanctioned upheaval that consequently shored up the dominant colonial hierarchies?Footnote 98 Or did it serve as an incisive challenge to the social order that transformed local hierarchies? Some people recalled insightful phrenological readings from years before, demonstrating how these moments could infuse narratives of personal identity and therefore hold social power. Bakhtin’s premise of the carnivalesque has been strongly critiqued for its assumption that challenges to the social system only occur during sanctioned festival periods, and that at all other times the social system functions smoothly.Footnote 99 In the evolving colonial societies of Australia and New Zealand, the phrenological lecture succeeded in playing with the normative model of social order precisely because the social order was a diaphanous thing easily punctured by wily opportunists.

What we do know for certain, though, is that the phrenologist occupied a recognised role as a disruptive force, often wreaking a combination of comedy and discomfort that sustained years of retelling.

0.7 Power in Nine Acts

Who was the popular phrenologist? Chapter 1 explores the lives and work of itinerant phrenological lecturers, who began to make a mark on Antipodean lecturing circuits from the 1850s. Unlike many earlier enthusiasts, members of the bourgeoisie who dabbled in the science out of curiosity or as a corollary to other roles, popular phrenologists thought commercially. Drawing on the lives of more than 140 lecturers working in the south-eastern Australian and New Zealand colonies, ranging from obscure practitioners to prominent figures such as Archibald Sillars Hamilton (see Figure 0.4), we study the contradictions of figures who adorned themselves with narratives of scientific glory while dragging themselves through the colonies on a soft underbelly of financial insecurity. However lowly a phrenologist’s social position, they could always seize upon the spectre of a more under-qualified phrenological ‘Other’ to shore up transient authority.

From studying the practitioner, Chapter 2 turns to audiences and their receptions. Resurrecting the phrenological lecture as a prominent genre of the mid-to-late nineteenth century, I examine how the visiting popular scientist became a talking point in new communities that took shape in the wake of gold rushes and colonial expansions. The defining act of reading heads in front of an assembled crowd, in which the phrenologist pronounced on the positive or negative attributes of each volunteer, allowed townsfolk to see their neighbours affirmed or ridiculed on stage. But who held the power in the encounter? And who was the butt of the joke?

On stage, phrenology often combined with other scientific and esoteric practices, most prominently mesmerism. Chapter 3 considers the phrenomesmeric show as high theatre on the performance circuits of the Tasman World, a melding of two scientific fads in which a lecturer feigned control of a human automaton. These displays often featured Indigenous performers who hammed up the extravagances of the period’s ethnographic shows. We meet Jemmy, an Aboriginal boy who participated in lectures in 1850 in the Melbourne Mechanics’ Institution, and Tamati Hapimana Te Wharehinaki, a Māori chief who toured with a phrenomesmerist in south-eastern Australia from 1866 to 1867. Although these shows presented a settler fantasy of Indigenous opponents subdued with a mere gesture, closer scrutiny reveals assertive employment relationships. What did Indigenous performers in popular scientific shows experience? And what benefits could they glean from the encounter?

While the first three chapters focus on stage cultures, the next two chapters venture into private or semi-private spaces.

The darker edge of authority plays out in Chapter 4, in which spiritual charisma combines with phrenology and mesmerism to allow privileged access to the bodies of women and children. A large proportion of professional phrenologists in the Tasman World also served as preachers or ministers of religion, with Wesleyan Methodists especially represented. Through the cases of the Methodist Minister Ralph Brown and the restorationist sect leader Albert Abbott, this chapter considers how expertise in oratory and tactile forms of healing could serve as transferable skills for phrenological ministers and preachers. Yet, although such practitioners faced scandal and even prosecution for their transgressions, the mobilities of the Tasman World – along with the gendered biases of the legal system and connected social myths about female behaviour and sexual assault – usually enabled them to slip unscathed into the next parts of their careers.

Remaining in south-eastern Australia, Chapter 5 focuses on lectures by popular phrenologists in 1884 and 1892 at the Maloga Mission and Cummeragunja Station (which superseded it) on the country of the Yorta Yorta traditional owners. Working from reports that discuss the racial content of the lectures and the supposedly positive responses of Aboriginal auditors, this chapter seeks to understand that reception. While acknowledging the power imbalances between missionary or station manager and Aboriginal residents, not to mention the biases of the European archive, this chapter considers the lectures within the context of the vibrant performance and political cultures of these sites to explore how Indigenous audiences might have experienced scientific showmanship.

From south-eastern Australia, the book sails to Aotearoa New Zealand, where phrenology appears in a multicultural world of Māori landowners and newcomers.

The material and social advantages wrung from phrenology came with additional complications for phrenologists of colour, as explored in Chapter 6. The phrenologist Lio Medo, who was of African descent, toured through Aotearoa New Zealand and Tasmania during the late nineteenth century. Even when boasting some degree of success, Medo also faced a shadowy double: the caricature of the ‘Black phrenologist’ born from the transnational popularity of minstrelsy and ‘Ethiopian’ plays. Haunted by this figure, Medo deftly navigated the exoticist shorthand of Black stage identities, adopting West Indian heritage by the end of his career. For Medo, phrenology improved on his previous career of ill-considered businesses, but his game of masking played out on touring circuits paved with broken glass.

The science also appeared in Māori negotiations over place and identity in a shifting world. By studying three separate episodes – set between 1878 and the early twentieth century – Chapter 7 considers phrenology as a tool used by Māori for light relief and as a healing alternative to European medicine. Meanwhile, during the early twentieth century, the vehement rejection of phrenology by leading Māori health reformers, who bundled it with other therapies practised by Māori faith-healers, known as tohungas, positioned phrenology within a contest over the best path to racial preservation. On one side stood proponents of European sanitation, medicine and administration, and on the other those who hybridised practices with a Māori worldview.

The final two chapters, which unfold largely in south-eastern Australia, consider phrenology within the contexts of nascent Federation, the sanitised city, and national mythologies.

At the turn of the twentieth century, in middle-class pockets of Melbourne, phrenology appeared in visions of Antipodean futures. As Chapter 8 details, although many popular phrenologists were opportunists, a handful of reform-minded practitioners picked up its tactile and discursive tools to promote ideas of national exceptionalism and racial fitness. Phrenology here intertwined with emerging discourses of the native European type, population health, heredity, altruistic socialism and the metaphysics of New Thought. A utopian science-fiction novel from 1889 and an optimistic periodical published by the Phrenological and Health Institute of Australasia, amid other sources, open up a cultural history of phrenology seized upon for national good. For middle-class female aficionados, the science offered a position of learned authority. Yet the applications that they proposed never won a place in government or institutional settings.

At the same time, phrenology became increasingly associated with an underworld of vagrancy and petty crime that besmirched what a modern city should look like. Chapter 9 opens with the sensational crimes of a phrenologist in Melbourne’s Eastern Market. There, and in other markets and arcades, phrenologists with outlandish names sold divination experiences infused with palmistry, astrology and even herbalism. For many of these practitioners, phrenology served as a cover for fortune telling – illegal under vagrancy laws – and other vices. While the largely female workforce of arcade phrenology became a target for police stings, on the road, the Australian bush phrenologist peddled itinerant science cloaked in tattered intellectualism. This Australian radical-masculinist figure – both real and imagined – made a virtue of sexual and racial chauvinism. Despite his transgressions, he carved his place in a national mythology increasingly disconnected from urbanised realities.

Important developments in our field and in the broader culture in recent years mean that the historical discipline increasingly – and rightly – seeks to decentre the white narrator and to elevate the voices of people writing and speaking from within groups that have been historically marginalised by colonisation and the supremacist ideologies that underpin it. I am myself an Australian-born daughter of European migrants, and in writing this book I have had to rely on documentary sources that were largely produced and circulated by earlier waves of settlers. This has been a confronting and uncomfortable task. I acknowledge that my position has allowed me to secure a temporary foothold in archival territory and hope that others will now be able to assess the terrain with further insight. I look forward to the challenging but exciting conversations that this work may generate.

0.8 Enduring Promise

After peaking during the 1880s and 1890s, phrenology’s Antipodean popularity as lecture entertainment dipped at the turn of the century, even though various people still listed their profession as such. The 1890s saw the rise of mass culture – dance crazes, phonographs, gaiety shows and cinema. These new forms did not instantly supplant earlier amusements, of course; phrenological lectures still took place, even during the 1920s, but these can be understood as traces of a diminishing practice. The drawcard of local knowledge and community-making offered by a phrenological lecture, along with its unruly head readings, became lost in modern star power and machines that reproduced cosmopolitan stories.Footnote 100

Other objects appeared in the phrenological toolbox. By the 1920s, phrenology’s services in advising parents and youths on career direction took on new iterations, surfacing in the emerging fields of the guidance movement and applied industrial psychology. In 1967, the Sydney phrenologist Haigwood Masters featured in an article in The Bulletin about the selection of the ‘Young Executive’. Masters, who for many years selected employees for the Woolworths Australia supermarket chain, shared his wisdom alongside a graphologist and psychologists from management consulting firms who administered standardised tests.Footnote 101 This was the cutting edge of workplace management.

Phrenology, contested from the outset and often grasped at in contemporary parlance as shorthand for dangerous foolishness, therefore hovered close to our own period. It swept a long tail behind it. During the mid-nineteenth century, as now, people scoffed at its promises while weighing it up in conversations with friends. Seductive in its simplicity, this practical science lured seekers of money, authority, infamy and raucous entertainment.

This is the story of phrenology’s promise in a changing world.